Abstract

Background

Hyperuricemia predisposes to gout, which may result in tophi, kidney stones, or urate nephropathy even kidney failure. Many metabolic risk factors and disorders has been recognized as a key risk factor contributing to development of hyperuricemia.

Aim

To determine the prevalence of hyperuricemia and its association with adiposity and dyslipidemia.

Methods

We recruited non-hospitalized participants (aged ≥35 years) in Xinjiang, a northwest part of China based on the Cardiovascular Risk Survey (CRS 2008–2012). Information of general health status, seafood or internal organs intake and history of disease were obtained by using an interview-based questionnaire. The levels of serum uric acid (sUA) and creatinine and lipid profiles were measured. A multivariate logistic regression model was performed to assess the association between prevalence of hyperuricemia and adiposity and dyslipidemia.

Results

This study recruited 16,611 participants, and 14,618 was included (mean age of 50.5 ± 12.6 years, 46.6% was males). The study population comprised three ethnic groups with 39.4% of Han, 32.6% of Uygur and 28% of Kazakh Chinese. The overall prevalence of hyperuricemia was 9.1% (95% CI: 8.6 to 9.6) and it was11.8% in men was 6.7% in women. The three ethnic groups also had different hyperuricemia prevalence with 15.4% in Han, 4.6% in Uygur and 5.5% in Kazakh Chinese, which corresponding to a respective mean sUA levels of 306.2 ± 86.9, 249.4 ± 76.1 and 259.8 ± 78.7 μmol/L. Participants with diabetes, hypertension or hypertriglyceridemia and higher blood urea nitrogen (BUN), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), fasting blood glucose (FBG), triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC) had higher levels of sUA (P < 0.001 respectively). Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that age, gender, ethnicity, drinking, obesity, waist circumference, TG (≥2.26 mmol/L), TC (≥6.22 mmol/L) are major risk factors for hyperuricemia. Compared to the 35–44-year age group [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1], the risk of hyperuricemia increased 1.61-fold in the 65–74-year age group (AOR = 1.61, 95% CI: 1.34–1.91; P < 0.001), and 1.71-fold in the 75- and older age group (AOR = 1.71, 95% CI: 1.27–2.29; P < 0.001). There was a 1.45-fold higher risk of hyperuricemia in men (AOR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.24–1.68; P < 0.001) compared to women. Further, the risk of hyperuricemia increased significantly with drinking (AOR = 1.36; 95% CI: 1.16–1.61; P < 0.001), overweight (AOR = 1.25; 95% CI: 1.06–1.48; P = 0.01), obesity (AOR = 1.28; 95% CI: 1.10–1.49; P < 0.001), waist circumference (AOR = 1.48; 95% CI: 1.24–1.78; P < 0.001), TC (≥6.22 mmol/L, AOR = 1.45; 95% CI: 1.19–1.75; P < 0.001), TG (≥2.26 mmol/L, AOR = 2.74; 95% CI: 2.39–3.14; P < 0.001).

Conclusions

These findings documented that the hyperuricemia is prevalent in the economically developing regions of northwest China. Hyperuricemia is associated with advanced age, male ender and general metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors. Obesity and dyslipidemia increase the risk of hyperuricemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hyperuricemia is an abnormal condition with higher level of uric acid in the blood [1]. In human, if the concentration of serum uric acid (sUA) reaches to 357 μmol/l (6 mg/dL) for women and 416 μmol/l (7.0 mg/dL) for men, hyperuricemia could be diagnosed [2,3,4]. Hyperuricemia is due to an imbalance of increased production of uric acid or/and decreased excretion of uric acid, which may result in serious complications including gout, tophi, kidney stones, or urate nephropathy even kidney failure [5, 6].

As a cardiovascular risk factor, sUA often accompanies metabolic syndrome, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia and obesity [7]. In developed countries, hyperuricemia was proved to be related to obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction [8] and body weight control can improved lifestyle, dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia and ameliorate metabolic risk factors [9]. Obesity in women and hypertriglyceridemia in men may aggravate hyperuricemia to develop gout [10]. In developing countries, for example, an Indian study reported that the prevalence of hyperuricemia increased significantly in obese population [11]. This is also the case in Bangladesh population [12]. A South African study reported that hyperuricemia was a component and an independent factor of the metabolic syndrome semi urban areas [13]. In Japan and China, a significant association among hypertriglyceridemia, hyperuricemia and obesity was also reported [14]. In Uygur Chinese who living in Xinjiang, Northwest China, an associated among elevated sUA, overweight/obesity and hypercholesteremia has been observed [15,16,17].

Previous studies have revealed that prevalence of hyperuricemia varies between countries and regions [5, 18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. A 21% prevalence of hyperuricemia during 2007–2008 in the US general population [20] and 11.9% in Italian adults (≥18 years) during 2005–2009 were reported [26]. A study estimated the prevalence of hyperuricemia in Chinese adults was 8.4% during 2009–2010 [23], while in Xinjiang (located in northwest China), it was 3.3 to 11.0% in different ethnic groups [16]. A number of studies also observed a trend of increase in hyperuricemia prevalence cross different countries and regions with times [20, 21, 23]. Genetic variations, different life style and some comorbidities e.g. hypertension, obesity, type 2 diabetes may all contribute to the development and onset of hyperuricemia [6, 27,28,29].

China is the largest developing country, and northwestern China especially Xinjiang is characterized by different ethnic groups and low socioeconomic status with a population of 21.8 million [30]. However, there is no such cross-sectional study designed to investigate the prevalence of hyperuricemia in Xinjiang adults age ≥ 35 years (As we know that hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia and other cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis are often well underway before middle age whereas clinical complications are common only after middle age. One aim of the CRS is designed to investigate risk factors for CVDs, so we study the participants aged 35 years and more.) and the association between hyperuricemia and adiposity and dyslipidemia. Therefore, the aim of the current study is to determine the prevalence of hyperuricemia in different ethnic populations and associated risk factors especially adiposity and dyslipidemia in this special region of China.

Methods

Study population

The Cardiovascular Risk Survey (CRS) is a cross-sectional, observational cohort study designed to investigate the prevalence, incidence, and risk factors for cardiovascular diseases and to determine the genetic and environmental contributions to atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease and cerebral infarction in the Han, Uygur, and Kazakh population in the Xinjiang province of West China and detailed description of study population and methods were described in the previous studies [31, 32]. We used a stratified sampling method to select a representative sample of the general population of Han, Uygur and Kazakh Chinese in this region. The sampling system covered major geographic areas cross Xinjiang. The first level of sampling was stratified by 3 regions including Eastern, Northern and Southern Xinjiang. According to geographical situation, economic status, ethnic distribution, life styles, the overall population size (high/low), proportion of urban population (high/low), and mortality rate (high/low), 7 strata (the second level) were then generated from 7 counties (Urumqi, Kelamayi, Hetian, Zhaosu, Fukang, Tulufan, and Fuhai). The third level of sampling was stratified by urban and rural locations. The fourth level of sampling was stratified by one socioeconomic strata in rural areas and one strata in urban areas [33, 34]. The participants were chosen and classified as urban and rural people based on the government record of registered residence, settlement and location of the people. The inclusion criteria included age ≥ 35 years, local residents in Xinjiang, complete data measurements and informed consents. Participants having one or more of the following conditions were excluded: regular use of cortisone, Cushing syndrome and other endocrinological disease causing body weight gain or loss; excess of alcohol intake and alcohol or drug abuse, other severe illnesses, mental disorders, malignancy, thrombolysis therapy, chronic inflammation, autoimmune disease, hepatic dysfunction, ascites, chronic renal failure or serum creatinine level > 2.5 mg/dL (not caused by hyperuricemia) and other serious diseases. In total, 1993 subjects were excluded from the study, and 14,618 participants from these seven areas (with a response rate of 88.8%) were included in this study (Fig. 1).

Anthropometric measurements

An interview-based questionnaire was used to gather information on the following: general health status, seafood or internal organs intake, history of diseases, etc. It was designed in the Chinese language but translated into Uygur or Kazakh language for those who didn’t understand Chinese. The questionnaire collected information including demographic, socioeconomic status and medical history. We also performed a physical examination including the measurements of height, body weight, systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP). Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg in light clothing with a mechanical scale. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm without shoes, with a commercial stadiometer (HW-900B OMRON, Japan). For those with physical deformity, Demi-span was measured, and height is then calculated from a standard formula. With the subjects standing and breathing normally, using a measuring tape parallel to the floor, waist circumference (WC) was measured at midpoint between the last palpable rib and the anterior superior iliac spine and the hip circumference (HC) was measured at the outermost points of the greater trochanters [35]. The ratio of WC to HC (WHR) was calculated. Blood pressure was measured three times with a 5 min interval, by tail cuff method.

Blood collection and laboratory test

Venous blood samples were drawn at overnight fasting condition (12 h). All routine full blood examination and blood biochemistry were performed using the commercially available automated platform, in the Central Laboratory of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University. These tests included sUA, total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), low- or high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C, HDL-C), fasting blood glucose (FBG), blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatine (with eGFR calculated).

Definition of cardiovascular risk factors

Hypertension was defined as history of hypertension and/or repeated systemic blood pressure measurements exceeding 140/90 mmHg [36]. Subjects with body mass index (BMI) between 25 and 28 kg/m2 were defined as overweight, and subjects with BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 were defined as obese [37, 38]. Participants with a WC ≥85 cm for men and WC ≥80 cm for women was defined as a risk factor [38]. Diabetes was defined as history or presence of diabetes and/or a fasting plasma glucose level ≥ 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) or a random glucose value ≥11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) or a 2-h plasma glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L during an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) plus signs or symptoms of diabetes. If there is no signs or symptoms of diabetes, the glucose level should be examined on another day [39]. Concentrations of glucose ≥6.1 mmol/L, TC ≥6.22 mmol/L, TG ≥2.26 mmol/L, LDL-C ≥ 4.14 mmol/L, and HDLC < 1.04 mmol/L were defined as hyperglycemia, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, hyper-LDL-C or hypo-HDL-C, respectively [40].

Statistical analysis

The collected data were independently recorded and verified by two staff members using EpiData 3.02 software (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark). Statistics were analyzed using SPSS21.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square or Fisher’s test and expressed as percentage. Changes of general and clinical characteristics and serum levels of biochemical parameters in the participants according to Quintiles of sUA were analyzed. To examine the variability between observers, we conducted inter- and intra-observation in some anthropometric parameters. Coefficients of inter- and intra-observer variability were calculated using a paired t-test. We used logistic regression models to analyze association between hyperuricemia and other potential metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors in two steps. We first applied a univariate logistic regression model to evaluate association among hyperuricemia and the variables listed in Table 1. We then performed a multivariate logistic regression model to assess the association between hyperuricemia and possible confounding factors used in the univariate analysis. Crude odds ratios (COR) and adjusted odds ratios (AOR) were calculated along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

General characteristics and biochemical parameters of study population

General characteristics and biochemical parameters are shown in Table 1. All of the study population were stratified into two groups according to presence of hyperuricemia. Those hyperuricemia participants tended to be elder, higher blood pressure, greater BMI, WC and HC (all P < 0.001). In addition, they tended to smoke more, and had more alcohol intake and seafood or internal organs intake. More hyperuricemia participants combined with metabolic diseases including hypertension, diabetes and lipid disorders than those without hyperuricemia (P < 0.001).

Of note, mean sUA in participants without or with hyperuricemia was 257.4 ± 66.7 and 442.1 ± 58.3 umol/l respectively (P < 0.001). Hyperuricemia participants had higher levels of FBG, TC, TG, serum creatinine and eGFR, and lower level of HDL-c compared with non-hyperuricemia participants (All P < 0.001).

Comparison of characteristic and serum biochemical parameter levels of the participants according to quintiles of sUA

Table 2 presents changes of characteristic and serum levels of biochemical parameters in participants according to Quintiles of sUA. Participants with higher levels of sUA were elder males and have higher BMI and blood pressure compared to those with lower levels of sUA (both P < 0.001). Among them, more people tended to smoke and drink (P < 0.001). Participants with diabetes, hypertension or hypertriglyceridemia and higher eGFR, FBG, TG, TC were associated with higher levels of sUA (all P < 0.001).

Variability between observers

Table 3 shows variability between observers. The coefficients of variability in both inter- and intra-observer were small for both height, weight measurements, et al. Regarding blood pressure, the variation of intra-observer was smaller than that of inter-observer. All data were within the 95% confidence interval. There was no systematic error between inter- and intra-observations (all P > 0.05). These results indicate that this method is reliable.

Changes of characteristic and serum levels of biochemical parameters of the participants according to ethnicities

Table 4 presents changes of characteristic and serum levels of biochemical parameters of the participants according to ethnicities. There were variations in the distributions of age, BMI, SBP,

DBP, alcohol intake, smoking and coffee/tea consumption. Han Chinese had lower BMI, but tended to have more drinking, smoking and coffee/tea consumption and highest mean level of sUA to other ethnic groups (P < 0.05 respectively). Uygur Chinese had lower levels of SBP, DBP, FBG and TC compared to other ethnic groups and had lowest mean level of sUA (P < 0.05 respectively). Kazakhs were more likely to have higher BMI, SBP, DBP, TC and HDL-c, while the level of sUA was less than Han Chinese but higher than Uygur Chinese (both P < 0.05).

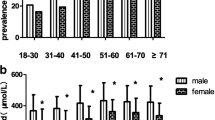

Prevalence of hyperuricemia and mean sUA estimations in Xinjiang in 2008–2012

The overall prevalence of hyperuricemia in Xinjiang adults aged ≥35 years during 2008–2012 was 9.1% (95% CI: 8.6–9.6), which was higher in men than in women (11.1% vs. 6.2%) and increased with aging (Table 5).

The prevalence of hyperuricemia was higher in rural area than in urban area (12.1% vs. 5.5%, P < 0.001) and it increased with advancing chronic kidney disease stage based on eGFR (> 15 umol/min/1.73m2). The ethnicity specific prevalence rate of hyperuricemia was much higher in Han than Uygur and Kazakh populations ((P < 0.001, Table 5).

Association between prevalence of hyperuricemia and adiposity and dyslipidemia

A univariate logistic regression showed that hyperuricemia was associated with age, gender (male), ethnicity, smoking, drinking, hypertension, diabetes, overweight/obesity, WC, WHR, TC (≥6.22 mmol/L), TG (≥2.26 mmol/L) and LDL-C (Table 6).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that age, gender, ethnicity, drinking, obesity, waist circumference, TG (≥2.26 mmol/L), TC (≥6.22 mmol/L) are major risk factors for hyperuricemia. Compared to the 35–44-year age group [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1], the risk of hyperuricemia was 1.61-fold in the 65–74-year age group (AOR = 1.61, 95% CI: 1.34–1.91; P < 0.001), and 1.71-fold in the 75- and older age group (AOR = 1.71, 95% CI: 1.27–2.29; P < 0.001). There was a 1.45-fold higher risk of hyperuricemia in men (AOR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.24–1.68; P < 0.001) compared to women. Further, the risk of hyperuricemia increased significantly with drinking (AOR = 1.36; 95% CI: 1.16–1.61; P < 0.001), overweight (AOR = 1.25; 95% CI: 1.06–1.48; P = 0.01), obesity (AOR = 1.28; 95% CI: 1.10–1.49; P < 0.001), waist circumference (AOR = 1.48; 95% CI: 1.24–1.78; P < 0.001), TC (≥6.22 mmol/L, AOR = 1.45; 95% CI: 1.19–1.75; P < 0.001), TG (≥2.26 mmol/L, AOR = 2.74; 95% CI: 2.39–3.14; P < 0.001, Table 6).

Discussion

In the current study, we found that the prevalence of hyperuricemia in Xinjiang was 9.1% during the period of 2008 to 2012. The risk of hyperuricemia in northwest China increased significantly with aging, different ethnicities, adiposity and dyslipidemia. People with more consumption of alcohol, overweight, obesity, higher WC, TC and TG tended to have hyperuricemia. Compared to Uygur and Kazakh Chinese, Han Chinese were more predisposed to hyperuricemia.

In our study we observed a 9.1% overall prevalence of hyperuricemia in Xinjiang which is higher than that in US general population (3.2%) during the period of 2007–2008 [20] and that in other region of Chinese adults (8.4%) during the period of 2009–2010 [23]. This may be attributed to aging [41], increased prevalence of overweight and obesity [17, 23], lifestyle changes, especially higher energy intake [42], increased consumption of foods rich in purines [43], diet soft drink [44], consumption of alcohol [24, 45] and physical inactivity [46]. In Xinjiang, Uygur, Han and Kazakh Chinese consist of the majority of population and account for 46, 40 and 7%, respectively [47]. We found that Han Chinese suffered more hyperuricemia than Uygur and Kazakh Chinese. The genetical background may have a potential influence in the prevalence of hyperuricemia among these different ethnic groups except lifestyle, a major factor. For example, previous studies reported that gene polymorphism in Uygur Chinese may be correlated with hyperuricemia such as ApoE E4, IL-8, IL-1RL1, IL-18 and SLC17A1 genes [48,49,50]. Hyperuricemia is a complicated metabolic disease with many risk factors. Among them, clarification of causal and protective genes would be very important in understanding the pathogenesis of hyperuricemia. To find ethnic difference and further exploring genetic variations would be a useful procedure for relevant biologic or metabolic evidence.

Weight gain was considered to be one strong risk factor for hyperuricemia. In consistent with previous reports [51,52,53], we found that risk of hyperuricemia was higher under the condition of obesity and overweight. In recent 40 years, along with rapid economic development in China, lifestyle has changed significantly. The prevalences of overweight and obesity increased from 22.8 to 30.1% and from 7.1 to 11.9% during the period of 2002–2012, respectively [54]. We also observed that participants with normal sUA levels had lower BMI than hyperuricemia participants. In Xinjiang, the prevalence of obesity ranged from 11.5 to 17.9%, in particular, the central obesity ranged from 53.9 to 59.9%, it is higher than the national levels [55]. And higher prevalence of obesity may be one explanation of higher prevalence of hyperuricemia in Xinjiang than national prevalence of hyperuricemia in China, while normal or lower BMI may be a protective factor.

Higher prevalence of hyperuricemia was also found to be correlated with dyslipidemia including higher TG and TC levels in adults aged 35 years and older adults. Hypertriglyceridemia is the most common risk factor for hyperuricemia. Peng et al. reported that higher TG, TC and LDL-c correlated significantly with elevated sUA, while HDL-C levels were negatively related to sUA levels [56]. Rathmann et al. showed that elevated TG level was an independent risk factor in males with hyperuricemia [57]. Takahashi et al. found that serum concentration of TG was associated with gout. Our results were consistent with those previous studies and we found higher levels of TG, TC, LDL-C and lower levels of HDL-C in hyperuricemia subjects although the association between higher levels of serum LDL-C and lower levels of HDL-C and higher prevalence of hyperuricemia remained elusive (with no significant difference in multiple regression analysis). According to these data, hyperuricemia may predict an unfavorable lipid profile, especially higher values of TG and TC levels. It needs more comprehensive intervention on those dyslipidemia patients combined with hyperuricemia.

Increase of seafood or internal organs intake was often considered as a cause of elevated sUA. It was reported that higher levels of consumption of seafood and dairy products were associated with increase in risk of gout [27]. The adverse effect of seafood or internal organs intake may be worse in patients with gout. Purines are broken down into uric acid. Purine intake had been proved to be associated with hyperuricemia and increased risk of incident gout [27]. A diet rich in purines from certain sources including seafood, meat and internal organs can raise sUA, which sometimes leads to gout [6]. In eastern coastal regions, such as Han Chinese in Qingdao and Hangzhou who had higher prevalence of hyperuricemia than Han Chinese in Xinjiang (25.3% vs. 16.9% vs. 15.4%) [24]. However, in our study, we found that seafood or/and internal organs intake was not an independent risk factor for development of hyperuricemia although hyperuricemia subjects consumed more seafood or/and internal organs. The exact reason for the discrepancy is unclear, more consumption of meat and dairy foods by the residents in Xinjiang than other regions of mainland of China may be a potential factor. Compared to Han and Uygur Chinese, Kazakh consumed more dairy products but the prevalence was not the lowest, and one of the possible explanation may be along with higher consumption of meat and less vegetables and fruits [58].

We also found ethnic difference of lipid levels among Han, Uygur and Kazakh populations. Regarding TG and TC levels, Han Chinese were significantly higher than Uygur and Kazakh Chinese. Lifestyle could affect TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, and TG levels in patients with dyslipidemia [59, 60]. Evidence showed that dyslipidemia contributed to both the onset and progression of atherosclerosis while the evidence-based treatment could decrease cardiovascular events [61]. It had been proven that the combination of a lipid-lowering diet and nutraceutical supplements could reduce LDL-C and increase HDL-C [62]. A recent review by Scicchitano P et al. pointed that natural nutraceuticals including niacin, omega-3 fatty acids, red yeast rice, fiber, plant sterols, and alpha linolenic acid (ALA) showed substantial effects in reductions in both serum lipid profiles [63]. Different ethnics have different social environment and diets. In Xinjiang, Uygur and Kazakh populations have a unique lifestyle. Kazakh Chinese consume more salt, wheaten food, meat and milk [64] while Uygur Chinese has a relatively special diet, such as high-sugar, high-fat, and low-dietary fiber diet [65]. There is difference in the lipid profile in different ethnic groups in Xinjiang [66]. And physical activity has important effects in dyslipidemia improvement [67, 68]. Beneficial effects of physical activity even intensities of exercise all lower cholesterol levels which may associated with body fat loss [69]. Base on the beneficial effects of physical activity, intensive aerobic exercise has been recommended for patients with dyslipidemia. For example, increasing physical activity to 30 min/day 5 times weekly and prolonging moderate-intensity aerobic exercise at 70–80% heart rate (HR) reserve, progressing to 85% HRmax could help to reduce LDL-C and TG and increase HDL-C [70]. However, for the nature of cross-sectional study, nutraceuticals effects on dyslipidemia were not included in the present study and more efforts may be made to investigate influence of diet habits and lifestyle changes in this special area.

Some limitations of the study deserved to be mentioned. First, cross-sectional nature of this study determines that all participants are not followed up, thus we don’t know the impact of changes in lifestyle on the prevalence of hyperuricemia. Second, although populations of Han, Uygur and Kazakh possessed majority population of Xinjiang, we didn’t recruit other 10 ethnicities accounting for 7% population of Xinjiang. Third, gout is an inflammatory arthritis associated with hyperuricemia and the epidemic status of gout should be studied along with hyperuricemia, while our study didn’t include this at the initial design. Fourth, due to variations in educational level and language barrier in this multiethnic region, information provided by participants may be incomplete. This collection of information may bring bias when performing data analysis. Despite these, our study provides an overall picture and latest information for the prevalence of hyperuricemia in three different ethic population and associated risk factors in Xinjiang.

Conclusions

These findings documented that the hyperuricemia is prevalent in the economically developing regions of northwest China. Hyperuricemia is associated with advanced age, male ender and general metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors. Obesity and dyslipidemia increase the risk of hyperuricemia. There is an urgent need to effectively manage these factors for preventing further increases in the burden of hyperuricemia and it also needs more comprehensive intervention on those individuals with metabolic disorders combined with hyperuricemia.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration

- FBG:

-

Fasting blood glucose

- HDL-C:

-

High density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C:

-

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- sUA:

-

Serum uric acid

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- WHR:

-

Waist-to-hip ratio

References

Choi HK, Mount DB, Reginato AM. Pathogenesis of gout. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:499–516.

Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann RL, MacDonald PA, Eustace D, Palo WA, Streit J, Joseph-Ridge N. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2450–61.

Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, Pascual E, Barskova V, Conaghan P, Gerster J, Jacobs J, Leeb B, Liote F, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: management. Report of a task force of the EULAR standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1312–24.

Perez-Ruiz F, Liote F. Lowering serum uric acid levels: what is the optimal target for improving clinical outcomes in gout? Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1324–8.

Eggebeen AT. Gout: an update. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:801–8.

Richette PB, T. Gout. Lancet. 2010;375:318–28.

Martínez-Quintana E, Tugores A, Rodríguez-González F. Serum uric acid levels and cardiovascular disease: the Gordian knot. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:E1462–6.

Oguri M, Fujimaki T, Horibe H, Kato K, Matsui K, Takeuchi I, Yamada Y. Obesity-related changes in clinical parameters and conditions in a longitudinal population-based epidemiological study. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2017;11:299–314.

Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, Torgerson J, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, Dahlgren S, Larsson B, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683–93.

Chen J-H, Pan W-H, Hsu C-C, Yeh W-T, Chuang S-Y, Chen P-Y, Chen H-C, Chang C-T, Huang W-L. Impact of obesity and hypertriglyceridemia on gout development with or without hyperuricemia: a prospective study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:133–40.

Remedios C, Shah M, Bhasker AG, Lakdawala M. Hyperuricemia: a reality in the Indian obese. Obes Surg. 2012;22:945–8.

Ali N, Perveen R, Rahman S, Mahmood S, Rahman S, Islam S, Haque T, Sumon AH, Kathak RR, Molla NH, et al. Prevalence of hyperuricemia and the relationship between serum uric acid and obesity: a study on Bangladeshi adults. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0206850.

Reimann M, Schutte AE, Malan L, Huisman HW, Malan NT. Hyperuricaemia is an independent factor for the metabolic syndrome in a sub-Saharan African population: a factor analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:638–45.

Nakamura H. Association of hyperuricemia with hyperlipidemia and obesity. Nihon Rinsho. 1996;54:3289–92.

Li NF, Wang HM, Yang J, Zhou L, Yao XG, Hong J. Serum uric acid is associated with metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the Uygur population. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2009;34:1032–9.

Yuan S, Xiao-Mei LI, Yi-Tong MA, Yang Y-N, Xiang MA, Huang Y, Zhen-Yan F, Xie X, Liu F, Wang L, Pan S. Epidemiological survey of hyperuricemia and gout in Xinjiang adult popIllation. Chin J Endocrinol Metab (in Chinese). 2011;27:570–2.

McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Maynard JW, Coresh J, Baer AN. Risk factors for incident hyperuricemia during mid-adulthood in African American and white men and women enrolled in the ARIC cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:347.

Karis E, Crittenden DB, Pillinger MH. Hyperuricemia, gout, and related comorbidities: cause and effect on a two-way street. South Med J. 2014;107:235–41.

Duan W, Zhang J, Ma Y, Cheng J. Prevalence and influencing factors of hyperuricemia among residents in Korla region of Xinjiang. Chinese General Practice. 2013;16:916–8.

Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and nutrition examination survey 2007-2008. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3136–41.

Nan H, Qiao Q, Dong Y, Gao W, Tang B, Qian R, Tuomilehto J. The prevalence of hyperuricemia in a population of the coastal city of Qingdao, China. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1346–50.

Liu R, Han C, Wu D, Xia X, Gu J, Guan H, Shan Z, Teng W. Prevalence of Hyperuricemia and gout in mainland China from 2000 to 2014: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:762820.

Liu H, Zhang XM, Wang YL, Liu BC. Prevalence of hyperuricemia among Chinese adults: a national cross-sectional survey using multistage, stratified sampling. J Nephrol. 2014;27:653–8.

Cai Z, Xu X, Wu X, Zhou C, Li D. Hyperuricemia and the metabolic syndrome in Hangzhou. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2009;18:81–7.

Song P, Wang H, Xia W, Chang X, Wang M, An L. Prevalence and correlates of hyperuricemia in the middle-aged and older adults in China. Sci Rep. 2018;8:4314.

Trifiro G, Morabito P, Cavagna L, Ferrajolo C, Pecchioli S, Simonetti M, Bianchini E, Medea G, Cricelli C, Caputi AP, Mazzaglia G. Epidemiology of gout and hyperuricaemia in Italy during the years 2005-2009: a nationwide population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:694–700.

Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G. Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1093–103.

Thapar K, Scheithauer BW, Kovacs K, Pernicone PJ, Laws ER Jr. p53 expression in pituitary adenomas and carcinomas: correlation with invasiveness and tumor growth fractions. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:765–70.

Hollis-Moffatt JE, Xu X, Dalbeth N, Merriman ME, Topless R, Waddell C, Gow PJ, Harrison AA, Highton J, Jones PB, et al. Role of the urate transporter SLC2A9 gene in susceptibility to gout in New Zealand Maori, Pacific Island, and Caucasian case-control sample sets. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3485–92.

Du GL, Liu ZH, Chen M, Ma R, Jiang S, Shayiti M, Zhu J, Yusufu A. Sheehan's syndrome in Xinjiang: clinical characteristics and laboratory evaluation of 97 patients. Hormones (Athens). 2015;14:660–7.

Xie X, Ma YT, Yang YN, Fu ZY, Li XM, Huang D, Ma X, Chen BD, Liu F. Polymorphisms in the SAA1/2 gene are associated with carotid intima media thickness in healthy Han Chinese subjects: the cardiovascular risk survey. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13997.

Liu F, Ma YT, Yang YN, Zhen YJ, Xie X, Li XM, Ma X, Chen BD, Huang Y, Shan CF, Gao XM. The prevalence of isolated systolic hypertension in adult populations from the Han, Uygur and Kazakh ethnic groups in Xinjiang, China. Blood Press. 2014;23:154–9.

Yang G, Hu J, Rao KQ, Ma J, Rao C, Lopez AD. Mortality registration and surveillance in China: history, current situation and challenges. Popul Health Metrics. 2005;3:3.

Xie X, Ma YT, Yang YN, Li XM, Liu F, Huang D, Fu ZY, Ma X, Chen BD, Huang Y. Alcohol consumption and ankle-to-brachial index: results from the cardiovascular risk survey. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15181.

Despres JP, Lemieux I, Prud'homme D. Treatment of obesity: need to focus on high risk abdominally obese patients. BMJ. 2001;322:716–20.

Writing group of 2004 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension. Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension. Chin J Cardiol (in Chinese). 2004;32:1060–4.

James PT, Leach R, Kalamara E, Shayeghi M. The worldwide obesity epidemic. Obes Res. 2001;9(Suppl 4):228S–33S.

Coorperative Meta-analysis Group of China Obesity Task Force (Correspondence: ZHOU Beifan. Department of Epidemiology FWH, Peking Union Medical College and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing 100037, China: Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference to risk factors of related diseases in Chinese adult population. Chin J Epidemiol 2002, 23:5–10.

World Health, Organization: Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications: report of a WHO consultation. Part 1, Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66040.

Joint Committee for Developing Chinese guidelines on P ToDiA. Chinese guidelines on prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia in adults. Chin J Cardiol (in Chinese). 2007;35:390–419.

Krishnan E, Bennett M, Chen L. Aging, not menopause, is associated with higher prevalence of hyperuricemia among older women. Menopause. 2014;21:1211–6.

Daniel CR, Cross AJ, Koebnick C, Sinha R. Trends in meat consumption in the USA. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14:575–83.

Choi HK, Liu S, Curhan G. Intake of purine-rich foods, protein, and dairy products and relationship to serum levels of uric acid: the third National Health and nutrition examination survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:283–9.

Choi JW, Ford ES, Gao X, Choi HK. Sugar-sweetened soft drinks, diet soft drinks, and serum uric acid level: the third National Health and nutrition examination survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:109–16.

Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G. Alcohol intake and risk of incident gout in men: a prospective study. Lancet. 2004;363:1277–81.

Williams PT. Effects of diet, physical activity and performance, and body weight on incident gout in ostensibly healthy, vigorously active men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1480–7.

Du GL, Su YX, Yao H, Zhu J, Ma Q, Tuerdi A, He XD, Wang L, Wang ZQ, Xiao S, et al. Metabolic risk factors of type 2 diabetes mellitus and correlated glycemic control/complications: a cross-sectional study between rural and urban Uygur residents in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162611.

Sun YP, Zhang B, Miao L, Wang XM, Yu JH, Luo L, Ying L, Xin G, Haliakpaer G, Xia H, Yao H. Association of apolipoprotein E (ApoE) polymorphisms with risk of primary hyperuricemia in Uygur men, Xinjiang, China. Lipids Health Dis. 2015;14:281–92.

Zhang B, Sun Y, Li Y, Yu J, Wang T, Xia H, Li C, Liu S, Yao H. Association analysis between genetic variants in interleukin genes among different populations with hyperuricemia in Xinjiang autonomous region. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:13432–40.

Wang T, Su Y, Wang Z, Ma Q, Yao H. Polymorphisms of SLC17A1 gene and their interaction with alcohol drinking among Uygur patients with hyperuricemia. Chin J Med Genet (in Chinese). 2015;32:881–5.

Bonora E, Targher G, Zenere MB, Saggiani F, Cacciatori V, Tosi F, Travia D, Zenti MG, Branzi P, Santi L, Muggeo M. Relationship of uric acid concentration to cardiovascular risk factors in young men. Role of obesity and central fat distribution. The Verona young men atherosclerosis risk factors study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996;20:975–80.

Joint WHO/FAO expert onsultation. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2003;916(i-viii):1–149.

Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Curhan G. Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:742–8.

National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Report on Chinese resident's chronic disease and nutrition. http://ennhfpcgovcn/2015–06/15/c_45788htm 2015.

He J, Guo H, Ding Y-S, Liu J-M, Zhang M, Zhang R-L, Zhang J-Y, Li S-G, Sun F, Shang-Zhi XU, Guo H-X. Epidemiological study on overweight and obesity among rural adult residents in Hazakh, Uygur and Han populations in Xinjiang. Chin J Epidemiol (in Chinese). 2013;34:1164–8.

Peng TC, Wang CC, Kao TW, Chan JY, Yang YH, Chang YW, Chen WL. Relationship between hyperuricemia and lipid profiles in US adults. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:127596.

Rathmann W, Funkhouser E, Dyer AR, Roseman JM. Relations of hyperuricemia with the various components of the insulin resistance syndrome in young black and white adults: the CARDIA study. Coronary artery risk development in young adults. Ann Epidemiol. 1998;8:250–61.

Li S, Guo S, He F, Zhang M, He J, Yan Y, Ding Y, Zhang J, Liu J, Guo H, et al. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired fasting glucose, associated with risk factors in rural Kazakh adults in Xinjiang, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:554–65.

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, Cooney MT, Corra U, Cosyns B, Deaton C, et al. 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the sixth joint task force of the European society of cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts7) developed with the special contribution of the European association for cardiovascular prevention & rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315–81.

Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, Goldberg AC, Gordon D, Levy D, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;2014(63):2889–934.

Ross R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–26.

Houston M. The role of nutraceutical supplements in the treatment of dyslipidemia. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;14:121–32.

Scicchitano P, Cameli M, Maiello M, Modesti PA, Muiesan ML, Novo S, Palmiero P, Saba PS, Pedrinelli R, Ciccone MM. Nutraceuticals and dyslipidaemia: beyond the common therapeutics. J Funct Foods. 2014;6:11–32.

Feng DW, Ma RL, Guo H, He J, Yan YZ, Muratbek, Niu Q, Li SG, Rui DS, Sun F, et al. Association of APOA1 gene polymorphisms (rs670, rs5069, and rs2070665) with dyslipidemia in the Kazakhs of Xinjiang. Genet Mol Res. 2016;15(2):gmr.15028094..

Yao XG, Meng J, Zhou L, Lin N, Hong J, Heizhati M, Li NF. Relationship between polymorphism of SOCS-3 and dyslipidemia in China Xinjiang Uygur. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:1338–46.

Yao XG, Frommlet F, Zhou L, Zu F, Wang HM, Yan ZT, Luo WL, Hong J, Wang XL, Li NF. The prevalence of hypertension, obesity and dyslipidemia in individuals of over 30 years of age belonging to minorities from the pasture area of Xinjiang. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:91.

Klem ML, Wing RR, McGuire MT, Seagle HM, Hill JO. A descriptive study of individuals successful at long-term maintenance of substantial weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:239–46.

Leon AS, Sanchez OA. Response of blood lipids to exercise training alone or combined with dietary intervention. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2001;33:S502–15..

Sheikholeslami DV, Ahmadi S, Dehrashid KA, Gharibi F. Changes in cardiovascular risk factors and inflammatory markers of young, healthy, men after six weeks of moderate or high intensity resistance training. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2011;51:695–700..

Mann S, Beedie C, Jimenez A. Differential effects of aerobic exercise, resistance training and combined exercise modalities on cholesterol and the lipid profile: review, synthesis and recommendations. Sports Med. 2014;44:211–21.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the partners and staff for their contribution to the study.

Funding

This research was funded by Xinjiang Science and Technology Support Project, grant number 2016E02072.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.T.M., X.M.G. and Y.N.Y.; methodology, F.L. and G.L.D.; software, F.L.; formal analysis, F.L.; investigation, F.L., G.L.D. and N.S.; resources, Y.T.M.; data curation, F.L.; writing, original draft preparation, G.L.D.; writing, review and editing, G.L.D.; visualization, G.L.D.; supervision, X.M.L., X.M.G. and Y.N.Y.; project administration, X.M.L., X.M.G. and Y.N.Y.; funding acquisition, Y.N.Y. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines (Ethical Approval Number: 20070215–01; Approval date: 15th, February 2007.), and the participants signed informed consent forms before being questioned and physical examined according to a protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, F., Du, GL., Song, N. et al. Hyperuricemia and its association with adiposity and dyslipidemia in Northwest China: results from cardiovascular risk survey in Xinjiang (CRS 2008–2012). Lipids Health Dis 19, 58 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-020-01211-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-020-01211-z