Abstract

Background

Adding 8-aminoquinoline to the treatment of falciparum, in addition to vivax malaria, in locations where infections with both species are prevalent could prevent vivax reactivation. The potential risk of haemolysis under a universal radical cure policy using 8-aminoquinoline needs to be weighed against the benefit of preventing repeated vivax episodes. Estimating the frequency of sequential Plasmodium vivax infections following either falciparum or vivax malaria episodes is needed for such an assessment.

Methods

Quarterly surveillance data collected during a mass drug administration trial in the Greater Mekong Subregion in 2013–17 was used to estimate the probability of asymptomatic sequential infections by the same and different Plasmodium species. Asymptomatic Plasmodium infections were detected by high-volume ultrasensitive qPCR. Quarterly surveys of asymptomatic Plasmodium prevalence were used to estimate the probability of a P. vivax infection following Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax infections.

Results

16,959 valid sequential paired test results were available for analysis. Of these, 534 (3%) had an initial P. falciparum monoinfection, 1169 (7%) a P. vivax monoinfection, 217 (1%) had mixed (P. falciparum + P. vivax) infections, and 15,039 (89%) had no Plasmodium detected in the initial survey. Participants who had no evidence of a Plasmodium infection had a 4% probability to be found infected with P. vivax during the subsequent survey. Following an asymptomatic P. falciparum monoinfection participants had a 9% probability of having a subsequent P. vivax infection (RR 2.4; 95% CI 1.8 to 3.2). Following an asymptomatic P. vivax monoinfection, the participants had a 45% probability of having a subsequent P. vivax infection. The radical cure of 12 asymptomatic P. falciparum monoinfections would have prevented one subsequent P. vivax infection, whereas treatment of 2 P. vivax monoinfections may suffice to prevent one P. vivax relapse.

Conclusion

Universal radical cure could play a role in the elimination of vivax malaria. The decision whether to implement universal radical cure for P. falciparum as well as for P. vivax depends on the prevalence of P. falciparum and P. vivax infections, the prevalence and severity of G6PD deficiency in the population and the feasibility to administer 8-aminoquinoline regimens safely.

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01872702, first posted June 7th 2013, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01872702. This study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov under NCT02802813 on 16th June 2016. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02802813

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Novel approaches to the curative treatment and prevention of vivax malaria are urgently needed to achieve the elimination of malaria. Currently reductions in vivax malaria prevalence and incidence are lagging behind the more successful falciparum malaria elimination efforts [1]. Unlike Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax infections relapse weeks to months after the initial attack [2]. Repeated relapses cause considerable morbidity, misery, and loss of income in vivax endemic areas [3]. Relapsing infections are also a persistent source of gametocytes, fuelling P. vivax transmission [4]. The triggers for hypnozoite activation are not completely understood, but acute febrile illness and by-products of haemolysis have been proposed [5,6,7].

The observation that people living in co-endemic regions have an increased rate of vivax malaria following a falciparum malaria episode compared to those who did not have a recent falciparum malaria episode suggests that in co-endemic regions a falciparum infection is a risk factor for vivax relapse [7, 8]. The risk of vivax malaria following falciparum malaria has been estimated as low as zero in several locations and as high as 65% in Papua-New Guinea [9, 10]. The lack of efficacy of the schizontocidal treatment against recurrent vivax infections and the timing of relapses has been interpreted as evidence that vivax recurrences following falciparum malaria are due to reactivation of P. vivax hypnozoites [11]. However, the available molecular tools are not able to discriminate whether a P. vivax infection is a relapse or a new infection [12]. In co-endemic regions, it has been proposed that “universal radical cure” be given for both P. vivax and P. falciparum infections [9].

The only class of drugs that can eliminate hypnozoites and hence prevent vivax relapse are the 8-aminoquinoline primaquine and tafenoquine [13, 14]. The small but real risk of haemolysis in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficient individuals after the administration of 8-aminoquinoline regimens is a major barrier to the uptake of radical curative regimens and slows the elimination of vivax malaria. With the increasing availability of robust and accurate point of care tests for G6PD deficiency, health care providers are increasingly able to prescribe 8-aminoquinoline to clear vivax infections without putting the patient at risk. There is a broad consensus on the benefits of adding a course of 8-aminoquinoline to the schizontocidal treatment of vivax malaria. Detecting and treating asymptomatic P. vivax carriers is more challenging. In co-endemic regions P. falciparum infections could serve as a marker for earlier P. vivax infections. In such a scenario, the inclusion of 8-aminoquinoline in the treatment P. falciparum infections in addition to vivax malaria (universal radical cure), could benefit the P. vivax infected patient and accelerate the elimination of P. vivax. The relative benefits of such proactive treatment depend to a large part on the probability of an episode of P. vivax parasitaemia following a P. falciparum infection. To get a better understanding of such potential benefits this study explores the probabilities of sequential Plasmodium infections using data from a trial of mass drug administrations (MDAs) in villagers living in four countries of the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS).

Methods

The data for the current study were collected during a cluster randomized trial conducted between 2013 and 2017 in Myanmar, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos [15]. The aim of the trial was to assess the effectiveness, safety, tolerability, and acceptability of mass administrations of three rounds of dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine (DHA–PPQ) with a single low dose primaquine (SLD PQ). The MDAs were conducted at months 0, 1, 2 in intervention villages. The MDA intervention was allocated by restricted randomization within pairs of villages matched for geographical proximity and parasite prevalence. Of the 4423 people residing during the MDAs in the 8 intervention villages 3790 (86%) completed at least one round (3 doses) of anti-malarials. In addition, there were 294 new-comers registered until month 12. The 4310 residents in 8 control villages at month 0 plus 733 new-comers who joined later were invited to participate in cross-over MDAs after 12 months (M12, M13, M14) with the exception of the residents in two control villagers in Myanmar who were offered MDAs at M9, M10, M11. The surveillance data analysed in the current study are from the first 12 months in the control and intervention villages in Myanmar, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos and 9 months in the control villages in Myanmar. The month 12 data from the control arm in Myanmar are not included in the analysis as cross-over MDA took place at month 9 because of accessibility concerns during the rainy season.

Surveillance

At M0, directly preceding the MDA in intervention villages and subsequently every 3 months, all residents of the study villages aged 6 months or older were invited to participate in cross-sectional prevalence surveys, including temporary inhabitants and migrant workers arriving after the MDA was completed. The presence or absence of each participant in the village during the previous period was assessed during the quarterly surveys. Venous blood (3 mL) was collected from all individuals aged ≥ 5 years, and 500 µL from children aged ≥ 6 months to 5 years. Participants with fever ≥ 37.5 °C were tested for malaria by rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) and malaria positive cases were treated according to national guidelines.

Laboratory

The blood samples were stored in a cool box in the field and then transported within 12 h to the local laboratory and processed by separation of plasma, buffy coat, and packed red blood cells, which were frozen and stored at − 80 °C. The frozen samples from Myanmar, Cambodia, and Lao PDR were transported monthly on dry ice to the Department of Molecular Tropical Medicine and Genetics in Bangkok, Thailand for DNA extraction, and high-volume ultrasensitive quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (uPCR). The samples from the Vietnam sites were shipped to the Oxford University Clinical Research Unit in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam for DNA extraction, and uPCR. Detailed description and evaluation of the uPCR methods have been reported previously [16].

Statistical analysis

The conditional probability of a P. vivax infection in a current survey was calculated given the Plasmodium infection status 3 months earlier (the previous survey), which could be a P. falciparum, a P. vivax, a mixed or no infection. Thus, the data point of each participant included in this analysis had the same exposure period. Only the status of infection 3 months earlier was included in this analysis. The risk of P. vivax infections following P. falciparum or P. vivax infections was assessed using risk ratios. The risk ratios were calculated as the ratio of the conditional probabilities of P. vivax following P. falciparum or P. vivax infections in the preceding survey to the conditional probability of having a P. vivax infection when there was no Plasmodium species detected previously. Since participants could contribute more than one episode of malaria species infection, we used the Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) model to account for repeated observations in the same study participant. A GEE model with log binomial link function was fitted to the outcome (present of subsequent P. vivax infection) conditional on the preceding infection status (P. falciparum, P. vivax, mixed or no infection). The conditional probabilities, risk ratio and their 95% confidence interval were obtained. The risk difference (RD) was calculated as the difference between the assumed cure rate of primaquine minus the observed conditional probability of having no subsequent P. vivax infection when P. falciparum was detected at the time of the survey 3 months earlier. The risk differences that account for clustering were calculated from the conditional probabilities. The 95% confidence intervals were calculated by first obtaining the standard error of the difference in probabilities. The standard errors were calculated by squaring each of the standard errors of the probabilities which were then summed up and the square root taken. Then the 95% confidence interval for the risk differences was calculated in the usual way of risk difference plus or minus 1.96 multiplied by the standard error.

Next, the number of P. falciparum infected individuals needed to treat (NNT) with 8-aminoquinoline in order to prevent one P. vivax infection where NNT = 1/(risk difference) were estimated. The estimates make the assumption that the radical cure using an appropriate dose of primaquine has a 99% cure rate, i.e. nearly all subsequent P. vivax infections could have been prevented if the participants been treated appropriately. We also estimated the number of P. vivax infected people needed to treat (NNT) with 8-aminoquinoline in order to prevent sequential same species P. vivax infections. The 95% confidence intervals for NNT were calculated by obtaining the inverse of the lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence intervals for the risk difference and reversed their order [17]. The standard error of the risk difference was assumed to be the same in the observed data and in the hypothetical data (in which cure rate was assumed to be 99%). The analysis was performed in Stata 15.0.

Results

Of the 9760 residents living in the 16 villages during the 12-month study period, 6235 residents (1372 from Myanmar, 2004 from Vietnam, 1267 from Cambodia, and 1592 from Laos) contributed 16,959 valid sequential paired test results included in this analysis. Of these, 534 (3%) had a P. falciparum monoinfection, 1169 (7%) a P. vivax monoinfection, 217 (1%) had mixed (P. falciparum + P. vivax) infections, and 15,039 (89%) had no Plasmodium infection in the initial survey.

As shown in Table 1, of the 534 participants who had an initial monoinfection with P. falciparum, 47 had a subsequent P. vivax infection detected at next survey (9%; 95% Confidence Interval: 7% to 12%). Of 1169 participants who had an initial mono P. vivax infection, 584 had a subsequent P. vivax infection detected at the next survey (45%; 95% CI 42% to 48%). Of the 217 participants with mixed P. vivax and P. falciparum infection 104 were found to have a subsequent P. vivax infection at the next survey (47%; 95% CI 40 to 54%). Out of the 15,039 participants who were initially found to be uninfected 515 had subsequently P. vivax infections (4%; 95% CI 3 to 4%).

The risk of subsequent P. vivax infections following P. falciparum monoinfections was about two-fold increased (Risk Ratio 2.4, 95% CI 1.8 to 3.2) compared to the risk in uninfected participants. The risk of subsequent P. vivax infections following P. vivax in monoinfections was about 12 times increased (RR 12.2, 95% CI 11.0 to 13.6) compared to uninfected participants. When P. falciparum parasites were detected in participants with either mono- or mixed-infections during the preceding survey, the risk of subsequent P. vivax infection was almost 5 times increased (RR 4.9, 95% CI 4.1 to 5.9) compared to uninfected participants.

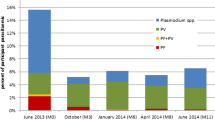

Table 2 summarizes the number of individuals needed to be treated with 8-aminoquinoline in order to prevent one P. vivax infection. Assuming that radical cure will prevent 99% of subsequent P. vivax infections (relapse), treatment of 12 individuals with asymptomatic P. falciparum mono-infections with an appropriate 8-aminoquinoline regimen will prevent one P. vivax infection (NNT 12, 95% CI 9 to 22) while treatment of 2 P. vivax mono-infected individuals will prevent one sequential P. vivax infection (NNT 2, 95% CI 2 to 3). The number of P. falciparum mono-infected cases to be treated with 8-aminoquinoline to prevent one P. vivax infection varied between study sites (Fig. 1). In Laos, the country with the highest baseline P. falciparum prevalence (7%), 12 (95% CI 7 to 33) P. falciparum infections would need to be treated with an 8-aminoquinoline to prevent one P. vivax infection and in Cambodia, with a baseline P. falciparum prevalence of 2%, 37 (95% CI 8 to ∞) P. falciparum cases would need to be treated.

Numbers individuals with P. falciparum (blue) or P. vivax (red) monoinfections that need to be treated with an appropriate 8-aminoquinoline regimen to prevent one P. vivax infection, assuming 99% P. vivax radical cure rate by country of the study site. (Pf %, Pv %): Pf monoinfection and Pv monoinfection baseline prevalence for each country

Discussion

Following asymptomatic P. falciparum monoinfections participants had a 9% probability of having an asymptomatic P. vivax infection at the next survey compared to a 4% probability in the absence of previously detected Plasmodium species. Only two people with P. vivax infections need to be treated to prevent one sequential P. vivax infection irrespective in which study site the infections were detected. By contrast, overall 12 asymptomatic monoinfections with P. falciparum need to be treated to prevent one subsequent P. vivax infection but this number varied by location.

A recent systematic review examined the risk of clinical vivax episodes following clinical falciparum malaria [9]. The investigators thought the risk of clinical vivax malaria episodes following falciparum malaria was mainly determined by the terminal half-life of the antimalarial drug used to treat the falciparum malaria episode and the periodicity of the P. vivax relapse pattern. In regions with short relapse periodicity including the GMS the risk was higher than in regions with longer intervals between relapses, i.e. regions further removed from the equator. By day 63 after a presentation with clinical falciparum malaria, independent of the type of schizontocidal drug administered for the falciparum episode, at least 15% of study participants had P. vivax parasitaemia in co-endemic countries.

One of the principal differences of the current study to earlier work is the use of asymptomatic infections to estimate probabilities and not clinical malaria episodes. There are good reasons to treat and clear asymptomatic infections in the interest of the infected individual [18] as well as to reduce and ultimately interrupt transmission, but asymptomatic infections may have different epidemiological characteristics and are likely to have different probabilities for subsequent vivax relapse than clinical malaria episodes. Second the current study detected infections in quarterly intervals. Events occurring after P. falciparum infection but ending before the next quarterly survey were missed by the current analysis. Using the quarterly surveys and in the absence of appropriate genotyping, we were unable to distinguish vivax re-infections or relapses from persistent infections. A recent analysis of data from the study site in Vietnam showed that asymptomatic P. vivax as well as P. falciparum infections persisted frequently for months in the absence of a curative treatment [19]. The number needed to treat (NNT) is an epidemiological measure used in communicating the effectiveness of a health-care intervention. The NNTs presented here do not include the reduction in vivax malaria transmission resulting from the implementation of the universal radical cure. The overall benefits of universal radical cure are therefore likely to be even larger than suggested by the NNTs.

Conclusion

Rational decision making whether to implement universal radical cure should consider benefits relative to safety risks. Considering the tangible and intangible costs of vivax malaria infections and the prospect of interrupting transmission, even treating 37 individuals with falciparum malaria to prevent one P. vivax episode, the highest number-needed-to-treat observed, seems justified. However, in the administration of 8-aminoquinoline safety concerns have a high priority. The introduction of robust and accurate tests which allow the quantitative estimation G6PD activity will make the administration of 8-aminoquinoline safer and the licensing of tafenoquine which can be administered as a single dose is likely to increase adherence to the radical cure. Good reasons to implement universal radical cure are accumulating. Whether the potential benefits outweigh the risks remains a judgement call for policymakers and needs to be based on local circumstances specifically the malaria and G6PD deficiency prevalence and the local capacity to diagnose G6PD deficiency correctly.

Data availability

The data are available upon request to the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit Data Access Committee (http://www.tropmedres.ac/data-sharing) for researchers and following the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit data access policy (http://www.tropmedres.ac/_asset/file/datasharing-policy-v1-1.pdf). Queries and applications for datasets should be directed to Rita Chanviriyavuth (rita@tropmedes.ac).

Abbreviations

- °C:

-

degrees Celsius

- µL:

-

microlitre

- 95% CI:

-

95% confidence interval

- DHA:

-

dihydroartemisinin

- G6PD:

-

glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GEE:

-

Generalized Estimating Equation

- GMS:

-

Greater Mekong Subregion

- M1, M2, M3, …:

-

Month 1, Month 2, Month 3, …

- MDA:

-

mass drug administration

- mL:

-

mililitre

- NNT:

-

number needed to treat

- PPQ:

-

piperaquine

- RD:

-

risk difference

- RR:

-

risk ratio

- SLDPQ:

-

single low dose primaquine

- uPCR:

-

high-volume ultrasensitive quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- Lao PDR:

-

Lao People’s Democratic Republic

- MORU:

-

Mahidol-Oxford Research Unit

- DP:

-

dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine

- Hb:

-

haemoglobin

References

WHO. World malaria report 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2017/en/. Accessed 25 Nov 2019.

Krotoski WA, Collins WE, Bray RS, Garnham PC, Cogswell FB, Gwadz RW, et al. Demonstration of hypnozoites in sporozoite-transmitted Plasmodium vivax infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:1291–3.

Price RN, Tjitra E, Guerra CA, Yeung S, White NJ, Anstey NM. Vivax malaria: neglected and not benign. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:79–87.

White NJ. Why do some primate malarias relapse? Trends Parasitol. 2016;32:918–20.

Shanks G. Hemolysis as a signal to initiate Plasmodium vivax relapse. In: 6th international conference on Plasmodium vivax research, Manaus, Brazil. Oral Presentation, 2017. https://icpvr.org/index.php?menu=programa. Accessed 28 Aug 2018.

Shanks GD, White NJ. The activation of vivax malaria hypnozoites by infectious diseases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:900–6.

White NJ. Determinants of relapse periodicity in Plasmodium vivax malaria. Malar J. 2011;10:297.

Douglas NM, Nosten F, Ashley EA, Phaiphun L, van Vugt M, Singhasivanon P, et al. Plasmodium vivax recurrence following falciparum and mixed species malaria: risk factors and effect of antimalarial kinetics. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:612–20.

Commons RJ, Simpson JA, Thriemer K, Hossain MS, Douglas NM, Humphreys GS, et al. Risk of Plasmodium vivax parasitaemia after Plasmodium falciparum infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:91–101.

Karunajeewa HA, Ilett KF, Mueller I, Siba P, Law I, Page-Sharp M, et al. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of piperaquine and chloroquine in Melanesian children with uncomplicated malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:237–43.

Imwong M, Nakeesathit S, Day NP, White NJ. A review of mixed malaria species infections in anopheline mosquitoes. Malar J. 2011;10:253.

Imwong M, Snounou G, Pukrittayakamee S, Tanomsing N, Kim JR, Nandy A, et al. Relapses of Plasmodium vivax infection usually result from activation of heterologous hypnozoites. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:927–33.

White NJ. The role of anti-malarial drugs in eliminating malaria. Malar J. 2008;7(Suppl 1):S8.

Straus B, Gennis J. Radical cure of relapsing vivax malaria with pentaquine–quinine; a controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1950;33:1413–22.

von Seidlein L, Peto TJ, Landier J, Nguyen TN, Tripura R, Phommasone K, et al. The impact of targeted malaria elimination with mass drug administrations on falciparum malaria in Southeast Asia: a cluster randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2019;16:e1002745.

Imwong M, Hanchana S, Malleret B, Renia L, Day NP, Dondorp A, et al. High throughput ultra-sensitive molecular techniques to quantify low density malaria parasitaemias. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;9:3003–9.

Altman DG. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ. 1998;317:1309–12.

Chen I, Clarke SE, Gosling R, Hamainza B, Killeen G, Magill A, et al. “Asymptomatic” malaria: a chronic and debilitating infection that should be treated. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1001942.

Thuy-Nhien N, von Seidlein L, Tuong-Vy N, Phuc-Nhi TL, Son DH, Huong-Thu PN, et al. The persistence and oscillations of submicroscopic Plasmodium falciparum and vivax infections over time in Vietnam: an open cohort study. Lancet Inf Dis. 2018;18:565–72.

Acknowledgements

We thank first and foremost the study communities who kindly agreed to participate in this project. We thank the institutions which allowed us to conduct the study and specifically, Ladda Kajeechiwa, Jordi Landier, Khin Maung Lwin, Lilly Keereecharoen, May Myo Thwin, Daniel M Parker, Jacher Wiladphaingern, Suphak Nosten, Stephane Proux, Vincent Corbel, Nguyen Tuong-Vy, Truong Le Phuc-Nhi, Do Hung Son, Pham Nguyen Huong-Thu, Nguyen Thi Kim Tuyen, Nguyen Thanh Tien, Le Thanh Dong, Dao Van Hue, Huynh Hong Quang, Chea Nguon, Chan Davoeung, Huy Rekol, Bipin Adhikari, Gisela Henriques, Panom Phongmany, Preyanan Suangkanarat, Atthanee Jeeyapant, Benchawan Vihokhern, Rob W. van der Pluijm, Yoel Lubell, Lisa J White, Ricardo Aguas, Cholrawee Promnarate, Pasathorn Sirithiranont, Benoit Malleret, Laurent Rénia, Carl Onsjö, Xin Hui Chan, Jeremy Chalk, Olivo Miotto, Krittaya Patumrat, Kesinee Chotivanich, Borimas Hanboonkunupakarn, Podjanee Jittmala, Nils Kaehler, Phaik Yeong Cheah, Christopher Pell, Mehul Dhorda, Mallika Imwong, Georges Snounou, Sue J Lee, Julie A Simpson, Sasithon Pukrittayakamee, Pratap Singhasivanon, Martin P Grobusch, Frank Cobelens, Frank Smithuis, Paul N Newton, Guy E Thwaites.

Funding

NJW is the recipient of the Wellcome Trust Award Number: 101148/Z/13/Z. AMD is the recipient of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Award Number: OPP10811420. LOMWRU and MORU receive core funding from the Wellcome Trust. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KP wrote the first draft of this article. KP, LvS, NPJD, AMD, PNN, NJW, and MMa developed the study concept. KP, PS, and PP curated the data. KP, FvL, MMu analysed the data. NPJD, AMD, NJW acquired the funding for the study. LvS, KP, PNN, MMa administered the project. KP, FvL, MI, GH, TP, BA, TJP, CP, MD, NPJD, FC, AMD, PNN, NJW, LvS, and MMa supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies were approved by the Cambodian National Ethics Committee for Health Research (0029 NECHR, dated 04 Mar 2013) the Institute of Malariology, Parasitology and Entomology in Ho Chi Minh City (185/HDDD dated 15 May 2013), the Institute of Malariology, Parasitology and Entomology in Qui Nhon (dated 14 Oct 2013), the Lao National Ethics Committee for Health Research (Ref No 013-2015/NECHR), Government of the Lao PDR and the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee (1015-13, dated 29 Apr 2013). Each participant or parent/guardian in the case on minors provided Individual, signed, informed consent or a fingerprint for illiterate participants countersigned by a literate witness. (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01872702).

Consent for publication

Not applicable as no personal data are included.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

von Seidlein, L., Peerawaranun, P., Mukaka, M. et al. The probability of a sequential Plasmodium vivax infection following asymptomatic Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax infections in Myanmar, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Malar J 18, 449 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-019-3087-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-019-3087-1