Abstract

Purpose

Genetic testing is widely used in diagnosing genetic hearing loss in patients. Other than providing genetic etiology, the benefits of genetic testing in pediatric patients with hearing loss are less investigated.

Methods

From 2018–2020, pediatric patients who initially presented isolated hearing loss were enrolled. Comprehensive genetic testing, including GJB2/SLC26A4 multiplex amplicon sequencing, STRC/OTOA copy number variation analysis, and exome sequencing, were hierarchically offered. Clinical follow-up and examinations were performed.

Results

A total of 80 pediatric patients who initially presented isolated hearing loss were considered as nonsyndromic hearing loss and enrolled in this study. The definitive diagnosis yield was 66% (53/80) and the likely diagnosis yield was 8% (6/80) through comprehensive genetic testing. With the aid of genetic testing and further clinical follow-up and examinations, the clinical diagnoses and medical management were altered in eleven patients (19%, 11/59); five were syndromic hearing loss; six were nonsyndromic hearing loss mimics.

Conclusion

Syndromic hearing loss and nonsyndromic hearing loss mimics are common in pediatric patients who initially present with isolated hearing loss. The comprehensive genetic testing provides not only a high diagnostic yield but also valuable information for clinicians to uncover subclinical or pre-symptomatic phenotypes, which allows early diagnosis of SHL, and leads to precise genetic counseling and changes the medical management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

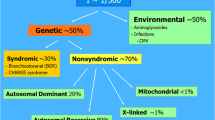

Childhood hearing loss affects 1 to 5 per 1,000 newborns [1]. It is acknowledged that the first 36 months after birth represent a critical period in cognitive and linguistic development [1]. At least 60% of childhood bilateral sensorineural hearing loss is due to genetic causes, of which 80% are nonsyndromic with isolated hearing loss, and 20% are syndromic with other abnormalities [2, 3]. To date, over 100 genes are reported to associate with nonsyndromic hearing loss (NSHL), and about 500 genes are associated with syndromic hearing loss (SHL) [4].

Early genetic diagnosis of SHL would significantly reduce other testing and provide opportunities for early intervention [5]. However, it is of great challenged in clinical settings because hearing loss is one of the most heterogeneous conditions. Many outpatients initially present isolated hearing loss and phenotypes other than hearing loss are subtle or late-onset. Moreover, some subtle phenotypes are hard to be identified in pediatric patients by otolaryngologists [6]. The SHL masquerading as NSHL is called NSHL mimics.

The SHL genes can be identified in NSHL patients due to genetic heterogeneity [6]. Of 102 NSHL probands without a causative variant in known NSHL genes, Bademci and co-authors identified four patients having pathogenic variants in SHL genes [7]. However, the characters of enrolled patients in this study were unknown. In pediatric patients with isolated hearing loss, the prevalence of SHL and NSHL mimics should be higher because some phenotypes are late-onset. Recently, two review articles reported that their unpublished data revealed the NSHL mimics comprise up to 25 – 30% of all genetic diagnoses in children with apparent NSHL [5, 8]. However, without clinical follow-up and examinations, it is unclear if these children would develop syndromic hearing loss.

With the advent of next-generation sequencing techniques, a growing number of clinical laboratories implemented genetic testing (hearing loss panel or exome sequencing) to uncover the genetic etiology of hearing loss [9]. Consensus recommendations from the International Pediatric Otolaryngology Group suggested comprehensive genetic testing for children with bilateral NSHL [10].The diagnostic yield of genetic testing for NSHL patients ranged from 40 to 65% among different studies [10], depending on the method used and ethnic background of patients. Other than the genetic etiology, the benefits of genetic testing in pediatric patients are less investigated, which requires clinical follow-up.

In this study, we enrolled 80 pediatric outpatients who initially presented isolated hearing loss and were clinically diagnosed as NSHL. Our comprehensive genetic testing achieved a high definitive diagnostic yield (66%) and likely diagnostic yield (8%). With the aid of genetic testing, following clinical follow-up and examinations, the clinical diagnosis of 11 (19%) molecular diagnosed patients was altered from NSHL to SHL or NSHL mimics. More importantly, they were referred to new specialists and more specific genetic counseling and medical management was conducted.

Material and methods

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Pediatric patient recruitment

Between 2018 and 2020, pediatric patients who met the following criteria were recruited at Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology: (1) outpatients who initially presented isolated hearing loss at the Department of Ear Nose & Throat; (2) bilateral hearing loss; (3) prelingual onset.

Genetic testing

Considering the significant contribution of the GJB2 and SLC26A4 gene in prelingual hearing loss in the East Asian population [11], the two genes were firstly analyzed via a multiplex PCR amplicon sequencing assay [12].When suspected, a GJB6 deletion analysis was suggested using low-pass genome sequencing [13]. Because STRC/OTOA plays a significant role in moderate hearing loss [14], these patients without a genetic diagnosis from the GJB2 or SLC26A4 gene were referred to STRC/OTOA analysis (SALSA® MLPA® P461 DIS probe mix kit, MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Patients with severe or profound hearing loss or negative for STRC/OTOA analysis were referred to exome sequencing. Exome sequencing was completed using KAPA HyperExome Probes (Roche, Pleasanton, CA, USA) accompanied by 100-bp paired-end sequencing on an MGISEQ-2000 platform (BGI-Wuhan, Wuhan, China). CNVs were called from WES data using ExomeDepth software version 1.0.7.18 [15]. The initial BAM files and base quality scores were realigned and recalibrated, respectively. After that, the final BAM files used for CNV prediction computation were generated. The hg19 reference was the used for alignment. The criteria evaluated for determining a CNV using this software comprised at least two consecutive altered exons in a region as a minimum cut-off number and a score higher than 50 for the reliability of an actual result.

Sequence variants were interpreted based on the expert specifications of variant interpretation guidelines for genetic hearing loss [16]. Specifically, a semi-automated variant interpretation platform, VIP-HL was used for variant interpretation [17]. 13 out of 24 ACMG/AMP rules, namely PVS1, PS1, PM1, PM2, PM4, PM5, PP3, BA1, BS1, BS2, BP3, BP4, and BP7, were automated activated based on aggregated information from external databases. While case/segregation (PM3, PS2/PM6, PS4, PP1, PP4, BS4, BP2, and BP5), and functional (BS3 and PS3) criteria were manually curated.

All reported sequence variants were confirmed via Sanger sequencing (single nucleotide variants), qPCR (exon-level copy number variations (CNV)), or low-pass genome sequencing (subchromosomal CNVs). Family segregation analysis was performed.

The positive genotype was defined as follows: (1) patients harboring pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants consistent with the inheritance pattern and segregating with hearing loss was defined as definitive diagnosis; (2) patients with pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in trans with a variant of uncertain significance in autosomal recessive condition was defined as likely diagnosis.

Clinical follow-up and diagnosis

When variants in SHL genes were identified in patients with isolated hearing loss, clinical follow-ups were conducted. Patients were recalled for further clinical examinations, which included but were not limited to, audiometry, physical examination, otoscopy, ophthalmoscopy, developmental assessment, and electrocardiogram analysis. The clinical follow-up ended in September 2021.

Finally, SHL was clinically diagnosed when phenotypes other than the hearing loss were uncovered by the date of clinical follow-up. If the genotypes were reported to be intensively associated with syndromic conditions in public literature, which did not present in the pediatric patients by the date of clinical follow-up, we define these patients as NSHL mimics.

Results

Cohort characteristics

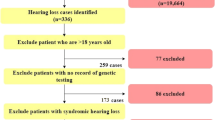

Between January 2018 and December 2020, a total of 80 patients with isolated, prelingual, bilateral hearing loss were enrolled. Overall, 73% (n = 58), 7% (n = 6), 19% (n = 15), 1% (n = 1) of patients were diagnosed with profound, severe, moderate, and mild sensorineural hearing loss, respectively. Most patients (85%, 68/80) reported no family history of hearing loss. Of 73 patients who received the newborn hearing screening at birth, 88% (64/73) were referred for audiological evaluations, and 12% (9/73) passed the hearing screening program (Additional file 2: Table S1). By the date of follow-up, 83% (66/80) patients received hearing aids or cochlear implants.

Genetic diagnosis

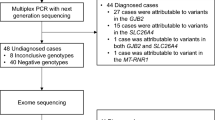

With a hierarchical genetic testing strategy, the definitive genetic etiology was confirmed in 53 out of 80 (66%) pediatric patients and likely genetic etiology was confirmed in 6 out of 80 (8%) (Fig. 1 and Additional file 3: Table S2). Specifically, 55% (44/80) patients had positive genotypes in the GJB2 or SLC26A4 gene. Of note, one child was diagnosed as a compound heterozygote of NM_004004.6(GJB2):c.299_300delAT and del(GJB6-D13S1854) (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Six patients with moderate hearing loss were negative for GJB2 and SCL26A4 sequencing. They were referred to STRC/OTOA analysis. As a result, a homozygous deletion in the STRC gene was identified in one (17%, 1/6) child (Additional file 1: Figure S2). The remaining 35 undiagnosed patients were referred to exome sequencing. Exome sequencing revealed the definitive and likely genetic etiology for 40% (14/35) patients. At the end, 26% (21/80) patients remain genetically undiagnosed.

Of 59 genetically definitive and likely diagnosed patients, CNVs were identified in 5 (8%) patients, including one subchromosomal CNV (P10), one GJB6 deletion (P11), one STRC homozygous deletion (P59), two exon-level CNVs (P54 and P62). Five (8%) patients harbored 7 novel variants, which were not reported either in literature or public databases. The autosomal recessive inheritance and autosomal dominant inheritance accounted for 86% (51/59) and 14% (8/59), respectively (Additional file 3: Table S2).

Genetic testing improves clinical diagnosis and medical management

Prior to genetic testing, the enrolled pediatric probands presented isolated hearing loss, which led to the clinical diagnosis of NSHL. However, genetic testing identified patients harboring variants in genes associated with SHL. These patients were referred to new specialists, and clinical follow-up and examinations were performed. As a result, phenotypes other than hearing loss were identified in five patients (P8, P10, P13, P46, and P62), suggesting a clinical diagnosis of SHL (Fig. 2 and Table 1). By the date of follow-up, six patients (P33, P38, P42, P43, P54, and P72) still presented isolated hearing loss, suggesting NSHL mimics. To sum up, genetic testing altered the clinical diagnosis in 19% (11/59) of genetically diagnosed pediatric patients (Table 2).

Syndromic hearing loss

In proband 8, a frameshift variant (c.3696_3706del) in MYO7A was identified in a homozygous state. In proband 46, two nonsense variants (c.6320G>A and c.6126C>G) in MYO7A were identified in compound heterozygous in trans. MYO7A is associated with Usher syndrome, type 1B (OMIM #276900), an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by retinitis pigmentosa, vestibular dysfunction, and hearing loss [18]. Clinical examinations via ophthalmoscopy revealed no abnormalities of retinitis pigmentosa in both two probands. However, via the Peabody Developmental Motor Scales [19], mild delayed motor development was confirmed at 42 months and 23 months in proband 8 and proband 46, respectively.

In proband 10, a 3.7 Mb heterozygous deletion in the chromosome 17p11.2 region was detected by exome sequencing, which was confirmed by low-pass genome sequencing. The 17p11.2 deletion causes Smith-Magenis syndrome (OMIM# 182290). The clinical features include distinctive craniofacial and skeletal features, global developmental delay, cognitive impairment, mental retardation, as well as hearing loss [20]. Further clinical examinations were counseled. Through the development assessment based on Revised Gesell Developmental Schedules [21], the mild developmental delay was clinically confirmed at the age of 17 months, which was not initially noticed by clinicians and parents.

In proband 13, exome sequencing detected a novel splicing variant in CREBBP (c.3699-1G>A). The loss of function variant of CREBBP is causative for Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome (OMIM# 180849) or Menke-Hennekam syndrome 1(OMIM# 618332) [22]. Further clinical examinations revealed that the proband lacks the facial and limb dysmorphism associated with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. Moreover, ultrasound inspection revealed a condition of inguinal hernia at the age of 4 years, which was consistent with the external genital abnormalities in individuals with Menke-Hennekam syndrome 1. After the counseling and physician assessment, a surgical repair of inguinal hernias was performed.

In proband 62, a novel heterozygous variant (Exon 8–9 del) in EYA1 was identified. It was inherited from his mother and maternal grandmother. Branchiootic syndrome 1 (OMIM #602588) caused by EYA1 variants showed a variable spectrum of manifestations, including hearing loss, branchial fistulae, preauricular pits, and renal abnormalities [23]. Although the parents declared no family history of other phenotypes except for hearing loss, a thorough clinical evaluation was conducted according to the genetic testing results. At the age of 4 years, a manifestation of slight preauricular pits, milder cup-shaped ears, and a small right ear was uncovered in the proband, consistent with the phenotype of Branchiootic syndrome 1. No further treatment or surgery was taken after the counseling because the phenotype is subtle.

Nonsyndromic hearing loss mimics

Variants related to SHL genes were identified in six probands (P33, P38, P42, P43, P54 and P72), whereas clinical phenotypes other than hearing loss were not observed, indicating a clinical diagnosis of NSHL mimics (Fig. 2 and Additional file 2: Table S1).

More specifically, two linked heterozygous variants (c.109G>A and c.263C>T) in GJB2, a de novo heterozygous variant in FGFR3 (c.749C>G), a heterozygous variant in MITF (c.877C>T) were identified in proband 33, 42, and 72 respectively. The reported variants caused Keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness (KID) syndrome (OMIM #148210), Muenke syndrome (OMIM #602849), and Waardenburg syndrome, type 2A (OMIM #193510), respectively. However, the three probands did not have additional clinical phenotypes after clinical examinations by the time of the latest follow-up.

Additionally, two variants in compound heterozygote in KCNQ1 (c.1684A>G and Exon 8–9 del) were identified by exome sequencing in proband 54. KCNQ1 is associated with Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome (JLNS, OMIM# 220400), which is characterized by profound congenital hearing loss and a prolonged QTc interval in the electrocardiography waveforms [6]. Electrocardiography detected a normal QTc interval in proband 54, suggesting NSHL mimics. Concerning life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias in JLNS patients [24], paddles for defibrillation were prepared in the process of cochlear implantation surgery at the age of 1 year. Regular cardiac monitoring was counseled for the prevention of sudden cardiac death.

In proband 38 and 43, a missense variant (c.641G>A) and a nonsense variant (c.877C>T) and in MITF were identified by exome sequencing, respectively, which led to the genetic diagnosis of Waardenburg syndrome, type 2A (OMIM# 193510). The missense variant in proband 38 was inherited from the hearing-impaired father and paternal grandmother. However, only the father demonstrated premature graying of hair during clinical follow-ups. The c.877C>T was identified in P43. Clinical follow-up revealed that the mother and maternal grandmother had a slight white forelock. The family members did not consider the abnormal pigmentation as a severe phenotype, thus did not report to clinicians in the recruitment.

Discussion

Childhood hearing loss is one of the most heterogeneous conditions. Early identification of hearing loss and understanding its etiology can assist with the prognosis and counseling of families [25]. In this study, we developed a comprehensive genetic testing approach, which identified the definitive genetic etiology for 66% (53/80) of pediatric patients, and the likely genetic etiology for 8% (6/80) of pediatric patients. More importantly, we uncovered that at least 19% of genetically diagnosed patients who were initially presenting isolated hearing loss were SHL or NSHL mimics. Benefit from the genetic testing and counseling, these patients were referred to new specialists for further assessment and regular monitoring, which ended the diagnostic odyssey.

Our tiered-based genetic testing strategy has a definitive and likely diagnostic yield of 74% in pediatric patients with prelingual hearing loss. It is higher than the previously reported rate ranging from 40 – 65% [10]. This might be attributable to high proportion of severe and profound patients (80%) in the study cohort. Another explanation is the existence of hotspot variants of the GJB2 and SLC26A4 gene in the East Asian population [11] and the exon-level and subchromosomal CNV analysis in our analyzing pipeline. In this study, 5/59 (8%) of genetically diagnosed patients were contributable to CNVs, including one subchromosomal CNV, one GJB6 deletion compound with a GJB2 variant, one STRC homozygous deletion, two exon-level CNVs. Nevertheless, the genetic spectrum reinforces the genetic heterogeneity of hearing loss, and a comprehensive genetic testing approach including exome sequencing, MLPA, low-pass genome sequencing is warranted.

SHL gene are commonly identified in children presenting with isolated hearing loss. Two review articles reported their unpublished data [5, 8]. Specifically, Shearer et al. reported that NSHL mimics comprise up to 25% of all genetic diagnoses in children [5]. Vona et al. reported that up to 30% of GJB2-mutation-negative children who are clinically identified as NSHL harbor pathogenic variants in genes associated with SHL [8]. However, without clinical follow-up and examinations, it is unknown if these patients would have subclinical or pre-symptomatic phenotypes. Herein, we reported that 19% of genetically diagnosed pediatric patients were clinically diagnosed SHL or NSHL mimics after genetic testing and clinical follow-up and examinations. Nevertheless, these data imply that a considerable portion of pediatric patients who initially present with NSHL would gradually develop SHL with age. More importantly, with the aid of genetic testing, early diagnosis prior to the presence of clinical phenotypes is feasible. Genetic testing provides valuable information for counseling and medical management and would significantly reduce other testing and provide opportunities for early intervention [5].

We wish to stress that the clinical diagnosis of a specific condition is of great challenge, particularly in a gene associated with NSHL and SHL. To not exaggerate the proportion of SHL and NSHL mimics, we only counted patients whose genotype is strongly associated with syndromic phenotypes in public literature. Following this rule, patients with pathogenic variants in CDH23 and SLC26A4 did not be counted in SHL, and they were conservatively categorized in NSHL. CDH23 is associated with Usher syndrome type ID (USH1D, OMIM #601067) and nonsyndromic autosomal recessive deafness 12 (OMIM #601386). Patients with a truncated mutation (nonsense, frameshift, or splice-site variation) are mostly associated with USH1D, whereas those with missense mutations usually appear to be nonsyndromic [26, 27]. However, USH1D caused by missense mutations was also reported [28]. Therefore, proband 61 harboring two missense variants (c.719C>T and c.7198C>G) in CDH23 were considered as NSHL in our study.

SLC26A4 is another good example to demonstrate the complexity. Mutations of SLC26A4 cause Pendred syndrome (OMIM #274600) and nonsyndromic autosomal recessive deafness 4 (OMIM #600791). Pendred syndrome is distinguished by the presence of thyroid abnormalities which are incompletely penetrant, adolescence onset, and partially influenced by nutritional iodine intake [29, 30]. To date, it is unclear why the same genotype would develop different phenotypes in different patients. Given all the ten children with positive genotypes in SLC26A4 had normal thyroid by the date of follow-up, we conservatively considered them as NSHL in our study. However, regular monitoring of the thyroid function was still suggested, which may be abnormal during adolescence [31]. Taken together, these results demonstrated the complexity of apparent isolated hearing loss, and longitudinal genotype–phenotype association studies are urgently needed.

Another important issue is to understand the underlying mechanisms of NSHL mimics. One possible explanation is that clinical phenotypes of a given syndrome are not yet present or not easily evaluated by otolaryngologists at the time when NSHL was diagnosed. For example, children diagnosed with Usher syndrome may manifest retinitis pigmentosa many years after the onset of hearing impairment [8]. Two children (P8 and P46) in our cohort were genetically diagnosed with Usher syndrome. By the latest follow-up, ophthalmoscopy revealed no abnormalities of retinitis pigmentosa in these patients. Regular ophthalmologic examinations to monitor the progression of the condition were counseled to the children’s guardians. Another example was the identification of JLNS caused by KCNQ1 in P54. Individuals with JLNS can have significant cardiac events in early childhood [6]. JLNS is thought to be one of the causes of sudden infant death syndrome. Although the measurement of electrocardiography was normal in P54, avoiding physical or emotional exertion was suggested. Additionally, subtle manifestations such as mild developmental abnormality confirmed in P8, P10 and P46, are prone to be ignored by otolaryngologists.

Variable penetrance might be another explanation for NSHL mimics. The same pathogenic variant associated with SHL may show incomplete penetrance and present differently between different people. Three patients (P38, P43 and P72) were genetically diagnosed with Waardenburg syndrome without additional clinical manifestations. However, the relatives harboring the same pathogenic variant displayed mild abnormal pigmentation of the hair. These variable manifestations within the same families suggest a variable penetrance of these variants and the phenotypic heterogeneity [32].

Another case of the effect of variable penetrance is the diagnosis with P33. The proband had a heterozygous c.263C>T (p.Ala88Val), in cis with an AR pathogenic variant (p.Val37Ile), in GJB2, which inherited from his nonsyndromic hearing-impaired mother. Further exome sequencing eliminated other possible causes of nonsyndromic dominant deafness. Previous studies have demonstrated c.263C>T is associated with Keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness (KID) syndrome, and may cause infant early lethality [33]. In our study, the proband and his mother only showed isolated hearing loss. This case represents a significant departure from what is known about KID syndrome. A similar situation has been reported with another lethal KID syndrome mutation in GJB2, p.Gly45Glu. The pathogenic effect of p.Gly45Glu can be confined by the presence of another heterozygous nonsense mutation p.Tyr136Ter, leading to healthy phenotype [34]. Likewise, the pathogenic effect of p.Ala88Val was possibly confined by the AR pathogenic variant or other cis-regulatory variation [35], and showed an incomplete penetrance. In vivo expression analysis and In vitro function validations of the mutant allele are warranted.

In conclusion, syndromic hearing loss and nonsyndromic hearing loss mimics are common in pediatric patients who initially present with isolated hearing loss. The comprehensive genetic testing provides not only a high diagnostic yield but also valuable information for clinicians to uncover subclinical or pre-symptomatic phenotypes, which allows early diagnosis of SHL, and leads to precise genetic counseling and changes the medical management.

Data availability

The data used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Gifford KA, Holmes MG, Bernstein HH. Hearing loss in children. Pediatr Rev. 2009;30(6):207–15.

Abou Tayoun AN, Al Turki SH, Oza AM, Bowser MJ, Hernandez AL, Funke BH, Rehm HL, Amr SS. Improving hearing loss gene testing: a systematic review of gene evidence toward more efficient next-generation sequencing-based diagnostic testing and interpretation. Genet Med. 2016;18(6):545–53.

Shearer AE, Hildebrand MS, Smith RJH: Hereditary hearing loss and deafness overview. In: GeneReviews(®). Edited by Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Mirzaa G, Amemiya A. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1999 Feb 14 [updated 2017 Jul 27].

Alford RL, Arnos KS, Fox M, Lin JW, Palmer CG, Pandya A, Rehm HL, Robin NH, Scott DA, Yoshinaga-Itano C, et al. American college of medical genetics and genomics guideline for the clinical evaluation and etiologic diagnosis of hearing loss. Genet Med. 2014;16(4):347–55.

Shearer AE, Shen J, Amr S, Morton CC, Smith RJ. Newborn hearing screening working group of the national coordinating center for the regional genetics n: a proposal for comprehensive newborn hearing screening to improve identification of deaf and hard-of-hearing children. Genet Med. 2019;21(11):2614–30.

Gooch C, Rudy N, Smith RJ, Robin NH. Genetic testing hearing loss: the challenge of non syndromic mimics. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;150: 110872.

Bademci G, Cengiz FB, Foster Ii J, Duman D, Sennaroglu L, Diaz-Horta O, Atik T, Kirazli T, Olgun L, Alper H, et al. Variations in multiple syndromic deafness genes mimic non-syndromic hearing loss. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31622.

Vona B, Doll J, Hofrichter MA, Haaf T. Non-syndromic hearing loss: clinical and diagnostic challenges. Medizinische genetik. 2020;32(2):117–29.

Abou Tayoun AN, Al Turki SH, Oza AM, Bowser MJ, Hernandez AL, Funke BH, Rehm HL, Amr SS. Improving hearing loss gene testing: a systematic review of gene evidence toward more efficient next-generation sequencing-based diagnostic testing and interpretation. Genet Med. 2015;18(6):545–53.

Liming BJ, Carter J, Cheng A, Choo D, Curotta J, Carvalho D, Germiller JA, Hone S, Kenna MA, Loundon N, et al. International Pediatric Otolaryngology Group (IPOG) consensus recommendations: Hearing loss in the pediatric patient. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;90:251–8.

Wang J, Xiang J, Chen L, Luo H, Xu X, Li N, Cui C, Xu J, Song N, Peng J, et al. Molecular diagnosis of non-syndromic hearing loss patients using a stepwise approach. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):4036.

Yang H, Luo H, Zhang G, Zhang J, Peng Z, Xiang J. A multiplex PCR amplicon sequencing assay to screen genetic hearing loss variants in newborns. BMC Med Genomics. 2021;14(1):61.

Dong Z, Zhang J, Hu P, Chen H, Xu J, Tian Q, Meng L, Ye Y, Wang J, Zhang M, et al. Low-pass whole-genome sequencing in clinical cytogenetics: a validated approach. Genet Med. 2016;18(9):940–8.

Shearer AE, Kolbe DL, Azaiez H, Sloan CM, Frees KL, Weaver AE, Clark ET, Nishimura CJ, Black-Ziegelbein EA, Smith RJ. Copy number variants are a common cause of non-syndromic hearing loss. Genome Med. 2014;6(5):37.

Plagnol V, Curtis J, Epstein M, Mok KY, Stebbings E, Grigoriadou S, Wood NW, Hambleton S, Burns SO, Thrasher AJJB. A robust model for read count data in exome sequencing experiments and implications for copy number variant calling. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(21):2747–54.

Oza AM, DiStefano MT, Hemphill SE, Cushman BJ, Grant AR, Siegert RK, Shen J, Chapin A, Boczek NJ, Schimmenti LA, et al. Expert specification of the ACMG/AMP variant interpretation guidelines for genetic hearing loss. Hum Mutat. 2018;39(11):1593–613.

Peng J, Xiang J, Jin X, Meng J, Song N, Chen L, Abou Tayoun A, Peng Z. VIP-HL: Semi-automated ACMG/AMP variant interpretation platform for genetic hearing loss. Hum Mutat. 2021;42(12):1567–75.

Nakanishi H, Ohtsubo M, Iwasaki S, Hotta Y, Takizawa Y, Hosono K, Mizuta K, Mineta H, Minoshima S. Mutation analysis of the MYO7A and CDH23 genes in Japanese patients with Usher syndrome type 1. J Hum Genet. 2010;55(12):796–800.

van Hartingsveldt MJ, Cup EH, Oostendorp RA. Reliability and validity of the fine motor scale of the Peabody Developmental Motor Scales–2. Occup Ther Int. 2005;12(1):1–13.

Girirajan S, Vlangos CN, Szomju BB, Edelman E, Trevors CD, Dupuis L, Nezarati M, Bunyan DJ, Elsea SH. Genotype–phenotype correlation in Smith-Magenis syndrome: evidence that multiple genes in 17p11.2 contribute to the clinical spectrum. Genetics in Medicine. 2006;8(7):417–27.

Yang J, Hu L, Zhang Y, Shi Y, Jiang W, Song C. Gesell developmental schedules scores and the relevant factors in children with down syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2020;33(4):539–46.

Banka S, Sayer R, Breen C, Barton S, Pavaine J, Sheppard SE, Bedoukian E, Skraban C, Cuddapah VA, Clayton-Smith J. Genotype–phenotype specificity in Menke-Hennekam syndrome caused by missense variants in exon 30 or 31 of CREBBP. Am J Med Genet A. 2019;179(6):1058–62.

Wang Y-g, Sun S-p, Qiu Y-l, Xing Q-h. Lu W: A novel mutation in EYA1 in a Chinese family with Branchio-oto-renal syndrome. BMC Med Genet. 2018;19(1):139.

Qiu Y, Chen S, Wu X, Zhang WJ, Xie W, Jin Y, Xie L, Xu K, Bai X, Zhang HM, et al. Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome due to a novel compound heterozygous KCNQ1 mutation in a Chinese family. Neural Plast. 2020;2020:3569359.

Lieu JEC, Kenna M, Anne S, Davidson L. Hearing loss in children: a review. JAMA. 2020;324(21):2195–205.

Astuto LM, Bork JM, Weston MD, Askew JW, Fields RR, Orten DJ, Ohliger SJ, Riazuddin S, Morell RJ, Khan S, et al. CDH23 mutation and phenotype heterogeneity: a profile of 107 diverse families with usher syndrome and nonsyndromic deafness. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71(2):262–75.

Ramzan K, Al-Numair NS, Al-Ageel S, Elbaik L, Sakati N, Al-Hazzaa SAF, Al-Owain M, Imtiaz F. Identification of novel CDH23 variants causing moderate to profound progressive nonsyndromic hearing loss. Genes. 2020;11(12):1474.

Becirovic E, Ebermann I, Nagy D, Zrenner E, Seeliger MW, Bolz HJ. Usher syndrome type 1 due to missense mutations on both CDH23 alleles: investigation of mRNA splicing. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(3):452–452.

Miyagawa M, Nishio SY, Usami S. Deafness gene study C: mutation spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlation of hearing loss patients caused by SLC26A4 mutations in the Japanese: a large cohort study. J Hum Genet. 2014;59(5):262–8.

Honda K, Griffith AJ. Genetic architecture and phenotypic landscape of SLC26A4-related hearing loss. Hum Genet. 2021;141:455–64.

Ito T, Muskett J, Chattaraj P, Choi BY, Lee KY, Zalewski CK, King KA, Li X, Wangemann P, Shawker T, et al. SLC26A4 mutation testing for hearing loss associated with enlargement of the vestibular aqueduct. World J Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;3(2):26–34.

Somashekar PH, Girisha KM, Nampoothiri S, Gowrishankar K, Devi RR, Gupta N, Narayanan DL, Kaur A, Bajaj S, Jagadeesh S, et al. Locus and allelic heterogeneity and phenotypic variability in Waardenburg syndrome. Clin Genet. 2019;95(3):398–402.

Lilly E, Bunick CG, Maley AM, Zhang S, Spraker MK, Theos AJ, Vivar KL, Seminario-Vidal L, Bennett AE, Sidbury R, et al. More than keratitis, ichthyosis, and deafness: Multisystem effects of lethal GJB2 mutations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(3):617–25.

Ogawa Y, Takeichi T, Kono M, Hamajima N, Yamamoto T, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Revertant mutation releases confined lethal mutation, opening Pandora’s box: a novel genetic pathogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(5): e1004276.

Castel SE, Cervera A, Mohammadi P, Aguet F, Reverter F, Wolman A, Guigo R, Iossifov I, Vasileva A. Lappalainen TJNg: Modified penetrance of coding variants by cis-regulatory variation contributes to disease risk. Nat Genet. 2018;50(9):1327–34.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Funding

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 81771003 and No. 82071058 to Dr. Sun).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZP and YS designed the study, JX and YJ wrote and edited the manuscript in equal parts, JX, YJ, NS, SC, JS, WX, XS, ZP, YS contributed to the data analysis. All Authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the institutions received local institutional review board (IRB) approval to use these data in research (Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology-IRB 2021(S193) and BGI-IRB 21148). All patients, parents or legal guardians signed an informed consent for sample collection. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

Nana Song, Jiankun Shen, Xiangzhong Sun, and Zhiyu Peng were employed at BGI at the time of submission. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Pedigree with GJB6 deletion. Figure S2. Pedigree with STRC homozygous deletion.

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of patients evaluated in this study.

Additional file 3: Table S2.

The genetic diagnosis results of 80 patients.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiang, J., Jin, Y., Song, N. et al. Comprehensive genetic testing improves the clinical diagnosis and medical management of pediatric patients with isolated hearing loss. BMC Med Genomics 15, 142 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-022-01293-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-022-01293-x