Abstract

Background

Copy number variants (CNVs) are a well-recognized cause of genetic disease; however, methods for their identification are often gene-specific, excluded as ‘routine’ in screens of genetically heterogeneous disorders, and not implemented in most next-generation sequencing pipelines. For this reason, the contribution of CNVs to non-syndromic hearing loss (NSHL) is most likely under-recognized. We aimed to incorporate a method for CNV identification as part of our standard analysis pipeline and to determine the contribution of CNVs to genetic hearing loss.

Methods

We used targeted genomic enrichment and massively parallel sequencing to isolate and sequence all exons of all genes known to cause NSHL. We completed testing on 686 patients with hearing loss with no exclusions based on type of hearing loss or any other clinical features. For analysis we used an integrated method for detection of single nucleotide changes, indels and CNVs. CNVs were identified using a previously published method that utilizes median read-depth ratios and a sliding-window approach.

Results

Of 686 patients tested, 15.2% (104) carried at least one CNV within a known deafness gene. Of the 38.9% (267) of individuals for whom we were able to determine a genetic cause of hearing loss, a CNV was implicated in 18.7% (50). We identified CNVs in 16 different genes including 7 genes for which no CNVs have been previously reported. CNVs of STRC were most common (73% of CNVs identified) followed by CNVs of OTOA (13% of CNVs identified).

Conclusion

CNVs are an important cause of NSHL and their detection must be included in comprehensive genetic testing for hearing loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Copy number variants (CNVs) are genomic variants that alter the diploid state of a portion of the genome, either by increasing (duplications, triplications) or decreasing (deletions) the number of alleles. CNVs range in size from 50 bp, the size of a small exon, to 5 megabases, the limit of detection for cytogenetic microscopy; they therefore span the continuum of genetic variation between small insertions and deletions (indels) to large chromosomal alterations[1]. CNVs can be benign or pathogenic, with CNV-induced pathogenesis typically due to 1) changes in copy number of dosage-sensitive genes, 2) gene disruption, or 3) fusion events leading to novel genes[2].

Whereas the mechanism of formation of single nucleotide mutations or indels is errors of DNA replication and repair, genomic rearrangements that produce CNVs are driven primarily by genomic architecture[2]. CNVs can be categorized by mechanism of formation, which in turn defines characteristics specific to CNVs, such as breakpoints and recurrence likelihood. Three mechanisms of formation have been described and shown experimentally to account for the vast majority of CNVs in the human genome: 1) non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR), caused by segmental duplications or repetitive elements such as Alu or L1 repeats and leading to recurrent CNVs, 2) non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ), mediated in some instances by repetitive elements and leading to non-recurrent CNVs, and 3) fork stalling and template switching (FoSTeS), leading to non-recurrent CNVs (reviewed in[2]).

The growing appreciation of the importance CNVs in human disease reflects our better understanding of their formation and improved tools for their identification. The Human Gene Mutation Database contains 148,413 reported disease-causing mutations in 6,137 genes[3] (accessed February 2014). Of these mutations, 89.6% are single nucleotide changes and small (< 20 bp) indels. The remaining 15,072 (11.4%) are structural variants that include 10,968 deletions, 2,600 insertions, and 1,504 complex rearrangements. Examples of the contribution of CNVs to human genetic disease include Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy 1A (autosomal dominant), Gaucher disease (autosomal recessive), hemophilia A (X-linked) and mental retardation (complex genetics) (reviewed in[4]).

CNVs have also been identified as a cause of non-syndromic hearing loss (NSHL), the most well-known example being deletion of a segmental duplication region of chromosome 15 that includes the gene STRC and causes autosomal recessive NSHL (ARNSHL) at the DFNB16 locus[5, 6] or deafness-infertility syndrome (DIS) if the adjacent CATSPER2 gene also is involved[7]. Amongst the 89 genes involved in NSHL (this list includes genes that cause syndromic hearing loss that can mimic NSHL), CNVs have been reported in 18 (Table 1). To date, however, there have been more than 1,000 reported causative single nucleotide variants and indels in these same genes[8].

We suspected that CNVs are an under-recognized cause of deafness, a limitation associated with the traditional low throughput and low-resolution methods for identification of genomic alterations. Classic methods for CNV identification include: 1) karyotyping and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), a method limited to the resolution of a microscope; 2) array comparative genomic hybridization (array-CGH), a commonly used ‘high resolution’ CNV detection method that provides resolution to about 100 kb; and 3) assays such as multiplex ligation-dependent amplification (MLPA), customized array-CGH panels, and breakpoint mapping. While the resolution of these last methods is outstanding, their implementation is costly, time-consuming, and not scalable to the genome level. Additionally, these methods all rely on an isolated test for CNVs. The ideal genetic test should combine single nucleotide variant detection, indel detection and CNV identification. In this study we sought to determine the relative importance of CNVs as a cause of hearing loss through the use of a diagnostic platform that allows detection of all three of these types of variants simultaneously.

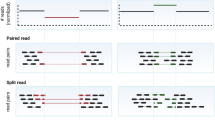

Targeted genomic enrichment coupled with massively parallel sequencing (TGE-MPS) has revolutionized clinical genetic testing by enabling specific genomic regions to be isolated, enriched and sequenced. TGE-MPS has been successfully applied to the diagnosis of several inherited diseases including deafness[9–11]. Following TGE, MPS generates millions of short sequencing reads that are mapped to the human reference genome to cover each sequenced nucleotide hundreds to thousands of times (referred to as fold-coverage). Variations from the reference genome are identified and annotated, and by capitalizing on sequencing depth of coverage between samples, alterations to the normal diploid genomic state can be identified and changes in copy number recognized (reviewed in[12]). Several groups, including ours, have successfully used these methods for identification of CNVs in patients with deafness and other genetic disorders[10, 13–15].

In this study we use TGE-MPS with integrated CNV detection as part of a comprehensive clinical diagnostic platform for hearing loss. We performed genetic testing on 686 patients with hearing loss and we identified CNVs in 16 deafness-causing genes, including 7 genes in which CNVs have heretofore not been described. We show that CNVs are a major contributor to hereditary hearing loss, comprising nearly one in five of all diagnoses for NSHL. These data mandate the inclusion of CNV detection as standard on all platforms used for the clinical diagnosis of genetic deafness.

Methods

Subjects

Records were examined for all patients who underwent clinical genetic testing for deafness at our laboratory over a two-year period beginning in January 2012. Testing was completed using the TGE-MPS panel we have developed called OtoSCOPE®. We included only unique probands by excluding familial testing and repeat testing. No patients were excluded based on age, age of onset of hearing loss, previous testing, or type of hearing loss. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Iowa; because it was a retrospective review of clinical data with a limited chance for harm to patients, informed consent was not obtained and instead the study was granted a full HIPAA waiver of authorization. To ensure anonymity of patients in this retrospective clinical study, patient information was de-identified, including providing ages in ranges and not identifying the sex of the patient. Our ethical approval did not allow deposition of patient data in to a public repository. This research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatics

TGE-MPS was completed as previously described (see[9] for details), using 3 μg of high-quality genomic DNA. Liquid-handling automation equipment was used to prepare the majority of libraries. We used OtoSCOPE v4 or v5, targeting 66 or 89 deafness-associated genes, respectively. We used v4 for 76 and v5 for 28 of the patients for whom we found CNVs, respectively (Additional file1). We include all NSHL genes known at the time each respective version of OtoSCOPE was made (v4 designed May 2011, and v5 designed November 2012) as well as genes that cause syndromic forms of deafness that mimic NSHL at an early age. In addition to the inclusion of newly discovered NSHL genes, OtoSCOPE v5 also includes several more NSHL mimics and additional probe coverage over the extended OTOA genomic region as well as the STRC genomic region to improve our ability to delimit the size of copy number variants at these loci. We also added probes to cover the gene CATSPER2, which is upstream of STRC and often involved in CNVs at this locus.

Sequencing was performed in pools of up to 48 samples per Illumina HiSeq flow cell using 100-bp paired-end reads. Sample quality control values were maintained as described previously[9]. All samples either met these requirements or were re-run.

Data were analyzed using a local installation of the open-source Galaxy software[16, 17] and a combination of several other open-source tools, including read mapping with Burrows-Wheeler Alignment (BWA)[18], duplicate removal with Picard, local re-alignment and variant calling with GATK Unified Genotyper[19], enrichment statistics with NGSRich[20], and reporting and annotation of variants with custom software[9].

For copy number analysis, we completed read mapping, duplicate removal, and re-alignment as described above. Next we used the indexed BAM file to call variants and generate a pileup using samtools[21] mpileup –Bf, retaining only the position and depth information for all variants called. We then performed CNV calling using a previously published tool written in R[22]. This method normalizes read-depth data by sample batch and compares median read-depth ratios using a sliding-window approach[22]. This tool is available by request from the original author (A Nord, personal communication). We performed this analysis using the 2011-07-01 version of the tool with default settings. CNV calls were curated through manual inspection.

We validated this method using MLPA spanning the STRC gene region on chromosome 15q15.3[23]. Our validation set of samples included DNA from 60 GJB2 negative probands with NSHL and 4 positive control individuals simultaneously tested with TGE-MPS and blinded MLPA testing. Results showed four homozygous deletions and four heterozygous deletions of this region with 100% concurrence between the methods.

All variant calls, including SNVs, indels and CNVs, were discussed at an interdisciplinary meeting (Hearing Group Meeting) that includes physicians, geneticists, genetic counselors, scientists and bioinformaticians. At these meetings, all available clinical, phenotypic and genetic data are used to determine the most likely genetic cause, if any, for hearing loss.

Results

Copy number variants identified

We identified 143 CNVs in 16 genes in 686 patients with hearing loss (Table 2; Additional file2). Of the patients studied, 15.2% (104/686) carried at least one CNV in a known deafness gene. We report CNVs in 7 of these genes for the first time, increasing the number of known deafness genes with CNVs by 28% to 25 total genes (Table 1). The overall CNV carrier frequency was 20.8% (143 CNVs/686 patients). We identified a probable genetic cause of hearing loss, be it a single nucleotide variant, indel, or CNV, in 38.9% of patients enrolled in this study (267/686). Detailed diagnostic results for these patients not pertaining to CNVs will be reported elsewhere.

Eighty-six CNVs were identified and considered causative in 18.7% (50/267) of diagnosed patients. Of these patients, the causative CNVs were categorized as follows: 21 (42%) homozygous CNVs (all deletions), 16 (32%) hemizygous CNVs found in conjunction with a second pathogenic change, 12 (24%) biallelic CNVs, and 2 (4%) CNVs that are part of a large heterozygous contiguous deletion of chromosome of at least 1.5 Mb on chromosome 22q12.3-22q13.1 in one patient (Additional file2). Homozygous CNVs are defined as the same change to copy number on both alleles while biallelic mutations are defined as a different copy number change on each allele (that is, a gene deletion and a gene conversion).

Of 50 patients with causative CNVs, 48 were diagnosed with ARNSHL. Two patients segregated apparent autosomal dominant NSHL (ADNSHL), one of whom carried both a single nucleotide mutation in DIAPH1 predicted to be pathogenic as well as a large heterozygous deletion of chromosome 22q12.3-22q13.1 of approximately 1.5 Mb that includes both MYH9 and TRIOBP. The extent of this deletion could not be resolved further due to the lack of other targeted genes on this chromosome. In this patient either the large CNV or the mutation in DIAPH1 may be responsible for the hearing loss. The size of the deletion and the absence of additional phenotypic data make a more definitive interpretation of these variants difficult. A subtle syndromic form of deafness is also possible. This patient was the only case in which two possible deafness-causing variants were identified.

The second patient segregating ADNSHL had moderate hearing loss and an out-of-frame deletion of the last 12 exons of MYO6 predicted to be causative (Additional file2). A deletion in TMC1, which can cause both ARNSHL and ADNSHL at the DFNB7/11 and DFNA36 loci, respectively, was considered pathogenic in trans with a second missense variant in a patient with ARNSHL. The only other CNV present in a gene implicated in ADNSHL was an in-frame duplication of exons 18 to 20 of EYA4. Mutations in EYA4 cause ADNHSL at the DFNA10 locus. For this study we categorized this CNV as non-pathogenic, although further study is required to determine whether this CNV is translated and pathogenic through a dominant-negative effect.

Most CNVs were deletions (92, 64.3%), followed by gene conversions (38, 26.6%), and duplications (13, 9.1%) (Table 2). The CNVs we detected ranged in size from one exon to over 1.5 Mb (chromosome 22q12.3-22q13.1).

The genomic architecture of hearing loss genes

To define the landscape of repeat elements that surround known NSHL genes, we performed a bioinformatics analysis of segdups (segmental duplications), Alu elements and L1 elements as these elements are sites of NAHR and mediate NHEJ[2]. Using data from RepeatMasker[24] we examined the presence of these repetitive elements within known deafness genes. Segdups, defined as regions with > 95% homology, are features that are causally implicated in recurrent CNVs mediated by NAHR and were identified in seven deafness genes: TSPEAR (4 segdups), OTOA (1), STRC (1), MYO3A (1), ESPN (1), OTOGL (1), CACNA1D (1). Both OTOGL and CACNA1D have homology to regions on different chromosomes, which predisposes to inter-chromosomal translocation via NAHR.

Alu and L1 elements are smaller repetitive elements and predispose to recurrent NAHR and non-recurrent NHEJ. Only six genes on our panel lacked Alu or L1 elements, and when we normalized the number of these elements by gene size, we found significantly more Alu elements, L1 elements, and total Alu + L1 elements in CNV-associated genes (paired t-test, P = 0.0003, P = 0.0104, P = 0.0139, respectively; Additional file3). In contrast, a comparison of all simple repeat elements normalized per gene found no significant difference between the 16 CNV-associated genes and the remaining genes on our panel (P = 0.6442), suggesting that the increased repetitive element burden could explain, at least in part, the gene distribution of CNVs we observed.

To illustrate the impact of CNV identification in the genetic evaluation of NSHL, we present three representative cases below.

Biallelic conversion of the STRC gene

Patient 45 was evaluated for mild sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) after failing the newborn hearing screen (NBHS). A diagnostic auditory brainstem response (ABR) at 4 weeks showed bilateral mild hearing loss and the patient was fitted with binaural amplification. There was no family history of hearing loss.

TGE-MPS identified a biallelic partial gene conversion involving STRC and the pseudogene, ψSTRC. As shown in Figure 1, the last 11 exons of STRC have been converted to ψSTRC leading to a functionally null STRC. This change represents the first report of a biallelic gene-pseudogene conversion at this locus. STRC encodes stereocilin, which localizes to the tips of outer-hair-cell stereocilia where it is hypothesized to form tip-link connectors between stereocilia as well as part of the connection between outer hair cells and the tectorial membrane[25]. Its mutation causes mild hearing loss. Additionally, because the STRC gene region is associated with a segdup that results in pseudogenes of both STRC and CATSPER2, homozygous deletions of the entire region (STRC and CATSPER2) cause DIS, characterized by mild SNHL in males and females and sperm motility defects and infertility in males[7].

A biallelic gene-pseudogene conversion of STRC is the causative mutation in patient 45. (a) Ratio plots showing apparent homozygous deletion of first 11 exons of STRC and duplication of first 11 exons of ψSTRC. (b) Hypothesized mechanism of gene-pseudo-gene conversion (non-allelic gene conversion in trans) and depiction of the biallelic change in the patient.

In our cohort of 686 patients, we identified causative mutations in STRC, including homozygous deletions, gene conversions, and heterozygous deletions in trans to a missense change, in 5.4% of patients (37/686; Table 2), accounting for 13.8% of all genetic diagnoses we provided (37/267) and making mutations in STRC one of the most common causes of ARNSHL, following closely behind mutations in GJB2 in primarily Caucasian populations. The carrier frequency for deletions, conversions, and duplications at the STRC locus was 4.7% (65/1,372 alleles), 2.6% (35/1,372 alleles), and 0.4% (5/1,372 alleles), respectively.

Forty-six patients carried at least one deletion in the STRC gene region (Additional file2). We were able to determine the status of CATSPER2 and ψSTRC in 13 of these patients because they were tested with OtoSCOPE v5 (Materials and methods; Additional file1). We found that the CATSPER2 gene was involved in 77.0% (10/13) of these patients, including one individual in which the deletion encompassed only CATSPER2 and ψSTRC and not STRC. Four individuals were homozygotes for a large contiguous STRC- ψSTRC-CATSPER2 deletion, indicating that they in fact are affected by DIS and not NSHL. All four of these patients are female and therefore will not have decreased fertility.

Deletion of OTOA in a Caucasian individual

Patient 14 was diagnosed with congenital moderate-to-severe SNHL after failing the NBHS, tested with otoacoustic emissions. A diagnostic ABR at 6 weeks confirmed the hearing loss and the patient was fitted with binaural amplification. There was no family history of hearing loss. The patient’s ethnicity was European-American.

TGE-MPS identified a homozygous deletion of the entire OTOA gene and the patient was diagnosed with DFNB22-related hearing loss (Figure 2). OTOA encodes otoancorin, an extracellular membrane protein that localizes to the interface between the tectorial membrane and the sensory epithelium[26]. It contains a glycophosphatidylinositol anchor that is thought to mediate attachment between the tectorial membrane and the greater epithelial ridge and spiral limbus during development, and with the spiral limbus in the mature cochlea. Mice lacking Otoa have hearing loss secondary to an abnormality of the tectorial membrane, which is attached at to the outer hair cells but detached from the spiral limbus[27].

To date, three mutations in OTOA have been reported within the Palestinian population: IVS12(+2)T > C[26], c.1067A > T, p. D356V[28], and a 500 kb deletion[29]. Two pathogenic OTOA mutations were recently discovered in the Pakistani population: p.G451D and p.P627S[30]. The deletion we report here is therefore the first report of a mutation in OTOA in a person of non-Middle-Eastern ethnicity. We identified 18 CNVs involving OTOA, including 15 deletions, 3 conversions and 3 duplications, making CNVs of OTOA the second most commonly identified CNVs after STRC. This frequency likely reflects the fact that exons 20 to 28 are part of a segdup of > 99% identity located 820 kb away[29]. In five cases, including this example, the CNV was causative.

A two exon deletion in TMC1

Patient 100 failed the NBHS and was subsequently diagnosed with profound, symmetric NSHL by follow-up ABR. There was no reported family history of hearing loss. TGE-MPS identified an incidental heterozygous change in GJB2 (c.101 T > C p.M34T) and a heterozygous two-exon deletion (exons 14 and 15) of TMC1 (Figure 3). Although the precise breakpoints could not be determined, the CNV encompasses the entirety of exons 14 (145 bp) and 15 (195 bp) and intron 14, making it between 1 and 20 kb in size (Figure 3). The deletion is out of frame and segregates opposite a c.545G > A p.Gly182Asp missense change in exon 11. Pathogenicity software shows this missense change to be damaging or deleterious by six in silico scoring methods (SIFT, PhyloP, Polyphen, LRT, MutationTaster, and GERP; see[9] for details) and thus is predicted to be pathogenic. The variant has a reported frequency in the Exome Variant Server of 0.000154.

A two-exon deletion of TMC1 is responsible for deafness in patient 100. (a) Ratio depth-of-coverage plot showing a two-exon heterozygous deletion. This deletion was found in trans with a missense change predicted to be pathogenic (c.1276G > A, p.Ala426Thr). (b) Highlighted region from UCSC genome browser RepeatMasker track demonstrates multiple short interspersed elements (SINEs; primarily Alu repeats), long interspersed elements (LINEs; including L1 repeats), and long terminal repeats (LTR) in this region. The two deleted exons are marked with asterisks. The hypothesized mechanism for this deletion involves these repeat elements and NAHR.

Mutations in TMC1 cause ARNSHL at the DFNB7/11 loci and ADNHSL at the DFNA36 locus[31]. More than 35 mutations have been reported as deafness causing[32, 33], including two large deletions leading to DFNB7/11-related hearing loss[31, 34]. This patient therefore carries the third deletion of this gene to be associated with NSHL and is the first report of a hemizygous deletion opposite a missense mutation.

Discussion

In this study, we performed comprehensive genetic testing of 686 patients with NSHL and showed that CNVs are a common contributor to hearing loss. We identified 143 CNVs in 16 deafness genes, including in 7 genes in which CNVs have not been reported (Table 1). Nearly one in three deafness genes (25 of 89 genes, 28%) carried a CNV and in aggregate CNVs contributed to nearly one in five (18.7%) genetic diagnoses for NSHL. These results mandate CNV screening in all comprehensive genetic testing platforms for deafness. Ideally, CNV detection should be incorporated in the diagnostic pipeline as a single test, which we accomplished by integrating a customized read-depth approach for variant detection to our TGE-MPS platform.

NAHR, the primary mechanism of formation of recurrent CNVs, is generally mediated by segdups or low-copy repeats[2]. Segdups range in size from 10 to 300 kb and typically must have > 95% homology for recombination to occur. Depending on the orientation of the segdup, an NAHR event can lead to duplications and deletions (segdups in parallel), inversions (segdups in opposition), or translocations (segdups on different chromosomes). NHEJ and FoSTeS, in comparison, are mediated by smaller repetitive elements, including short interspersed elements (SINES) such as Alu elements, and long interspersed elements (LINES) such as L1 repeats. Because NHEJ is dependent on repair of double-strand breaks, it leaves a signature ‘scar’ at the point of the repair. FoSTeS occurs during DNA replication and causes deletions, duplications and, when multiple FoSTeS events occur in sequence, complex rearrangements. ‘Joint points’ , repetitive elements and regions of microhomology of 2 to 3 bp are often the sites of FoSTeS.

The greatest number of CNVs was identified in STRC and OTOA, comprising 73% and 13% of all CNVs identified, respectively (Table 2). These two genes contain NAHR-predisposing segdups. We also identified segdups in TSPEAR, MYO3A, ESPN, OTOGL and CACNA1D, five genes in which CNVs have not been reported. In genes carrying CNVs in this study, we found a significantly higher number of small repetitive elements. We also identified several genes highly enriched for repetitive elements and thus likely candidates for CNVs (MARVELD2, CCDC50, LHFPL5, DIABLO, SLC26A5; see Additional file3 for a full list).

Although our TGE-MPS platform precludes the determination of breakpoints, we obtain outstanding exon-level resolution for CNV detection and can identify CNVs, single nucleotide changes and indels simultaneously. By tiling probes across pseudogenes in segdups we are able to reliably determine gene conversions and thereby improve our diagnostic ability.

The carrier frequency of the most common CNV, a deletion of the STRC region, was 4.7% in this study. Previous studies of patients with hearing loss using less sensitive SNP arrays for CNV detection have found carrier frequencies of 1.8% (659 patients)[6] and 6.4% (94 patients)[35]. Two other studies using array CGH reported a carrier frequency in individuals without hearing loss undergoing genetic testing for other reasons to be 1.1% and 1.6%[23, 36]. These data suggest that, in some populations, the carrier frequency of deletions of the STRC region may be more common than the carrier frequency of the most common mutations in GJB2. However, it is also important to consider the potentially pathogenic gene-pseudogene conversions at this locus. In this study we found the carrier frequency of these conversions to be 2.6%. Other platforms may not be able to accurately detect these potentially pathogenic conversions and so the carrier frequency for deleterious CNVs of this region is most likely under-reported.

Deletions of the STRC region are especially important to detect because concurrent deletion of the adjacent CATSPER2 gene leads to DIS in males[7]. In those patients for whom we used the modified version of our panel that includes the CATSPER2 gene, we identified its involvement in 10/13 cases with STRC deletion, suggesting that DIS is likely an under-diagnosed cause of hearing loss and male infertility.

This study has three minor limitations. First, the samples we studied were submitted for clinical testing and therefore detailed family history, clinical and/or phenotypic data were not available, precluding robust genotype-phenotype correlations and decreasing certainty of pathogenicity for CNVs identified. Second, we did not evaluate the carrier frequency of these CNVs in a control population, which remains an area of future study. And last, we used TGE-MPS for CNV detection, making it impossible to map breakpoints that occur outside targeted exonic regions. This constraint means that if a CNV spans multiple genes, it is impossible to determine its approximate size. However, when commonly occurring CNVs are recognized, additional probes can be added to any TGE-MPS platform to increase information content. For example, we have included more probes for the STRC/CATSPER2 region in recent versions of the platform used here.

Conclusion

CNVs are a common cause of NSHL. Their involvement in one in five genetic diagnoses by our laboratory using a comprehensive genetic testing platform mandates their identification in any clinical genetic diagnostic test for deafness. These data suggest that CNVs are likely to play an important role in other genetic disorders as well.

Abbreviations

- ABR:

-

auditory brainstem response

- ADNSHL:

-

autosomal dominant non-syndromic hearing loss

- ARNSHL:

-

autosomal recessive non-syndromic hearing loss

- bp:

-

base pair

- CGH:

-

comparative genomic hybridization

- CNV:

-

copy number variant

- DIS:

-

deafness-infertility syndrome

- FoSTeS:

-

fork stalling and template switching

- MLPA:

-

multiplex ligation-dependent amplification

- MPS:

-

massively parallel sequencing

- NAHR:

-

non-allelic homologous recombination

- NBHS:

-

newborn hearing screen

- NHEJ:

-

non-homologous end joining

- NSHL:

-

non-syndromic hearing loss

- SNHL:

-

sensorineural hearing loss

- TGE:

-

targeted genomic enrichment.

References

Zhang F, Gu W, Hurles ME, Lupski JR: Copy number variation in human health, disease, and evolution. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009, 10: 451-481., 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164217

Gu W, Zhang F, Lupski JR: Mechanisms for human genomic rearrangements. PathoGenetics. 2008, 1: 4-, 10.1186/1755-8417-1-4

Stenson PD, Mort M, Ball EV, Shaw K, Phillips AD, Coooper DN: The Human Gene Mutation Database: building a comprehensive mutation repository for clinical and molecular genetics, diagnostic testing and personalized genomic medicine. Hum Genet. 2014, 133: 1-9., 10.1007/s00439-013-1358-4

Stankiewicz P, Lupski JR: Structural variation in the human genome and its role in disease. Annu Rev Med. 2010, 61: 437-455., 10.1146/annurev-med-100708-204735

Verpy E, Masmoudi S, Zwaenepoel I, Leibovici M, Hutchin TP, del Castillo I, Nouaille S, Blanchard S, Lainé S, Popot JL, Moreno F, Mueller RF, Petit C: Mutations in a new gene encoding a protein of the hair bundle cause non-syndromic deafness at the DFNB16 locus. Nat Genet. 2001, 29: 345-349., 10.1038/ng726

Francey LJ, Conlin LK, Kadesch HE, Clark D, Berrodin D, Sun Y, Glessner J, Hakonarson H, Jalas C, Landau C, Spinner NB, Kenna M, Sagi M, Rehm HL, Krantz ID: Genome-wide SNP genotyping identifies the Stereocilin (STRC) gene as a major contributor to pediatric bilateral sensorineural hearing impairment. Am J Med Genet A. 2011, 158: 298-308.

Zhang Y, Malekpour M, Al-Madani N, Kahrizi K, Zanganeh M, Lohr NJ, Mohseni M, Mojahedi F, Daneshi A, Najmabadi H, Smith RJH: Sensorineural deafness and male infertility: a contiguous gene deletion syndrome. J Med Genet. 2007, 44: 233-240., 10.1136/jmg.2006.045765

The University of Iowa Deafness Variation Database. [http://deafnessvariationdatabase.org], []

Shearer AE, DeLuca AP, Hildebrand MS, Taylor KR, Gurrola J, Scherer S, Scheetz TE, Smith RJH: Comprehensive genetic testing for hereditary hearing loss using massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010, 107: 21104-21109., 10.1073/pnas.1012989107

Walsh T, Lee MK, Casadei S, Thornton AM, Stray SM, Pennil C, Nord AS, Mandell JB, Swisher EM, King M: Detection of inherited mutations for breast and ovarian cancer using genomic capture and massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010, 107: 12629-12633., 10.1073/pnas.1007983107

Shanks ME, Downes SM, Copley RR, Lise S, Broxholme J, Hudspith KA, Kwasniewska A, Davies WI, Hankins MW, Packham ER, Clouston P, Seller A, Wilkie AO, Taylor JC, Ragoussis J, Németh AH: Next-generation sequencing (NGS) as a diagnostic tool for retinal degeneration reveals a much higher detection rate in early-onset disease. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013, 21: 274-280., 10.1038/ejhg.2012.172

Zhao M, Wang Q, Wang Q, Jia P, Zhao Z: Computational tools for copy number variation(CNV) detection using next-generation sequencing data: features and perspectives. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013, 14: S1-

Shearer AE, Black-Ziegelbein EA, Hildebrand MS, Eppsteiner RW, Ravi H, Joshi S, Guiffre AC, Sloan CM, Happe S, Howard SD, Novak B, Deluca AP, Taylor KR, Scheetz TE, Braun TA, Casavant TL, Kimberling WJ, LeProust EM, Smith RJH: Advancing genetic testing for deafness with genomic technology. J Med Genet. 2013, 50: 627-634., 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101749

Park G, Gim J, Kim AR, Han KH, Kim HS, Oh SH, Park T, Park WY, Choi BY: Multiphasic analysis of whole exome sequencing data identifies a novel mutation of ACTG1 in a nonsyndromic hearing loss family. BMC Genomics. 2013, 14: 191-, 10.1186/1471-2164-14-191

Arboleda VA, Lee H, Sánchez FJ, Délot EC, Sandberg DE, Grody WW, Nelson SF, Vilain E: Targeted massively parallel sequencing provides comprehensive genetic diagnosis for patients with disorders of sex development. Clin Genet. 2013, 83: 35-43., 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01879.x

Goecks J, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J, : Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol. 2010, 11: R86-R2010. 11-8-r86, 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r86

The Galaxy Project. [http://usegalaxy.org], []

Li H, Durbin R: Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009, 25: 1754-1760., 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324

McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, Depristo MA: The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20: 1297-1303., 10.1101/gr.107524.110

Frommolt P, Abdallah AT, Altmüller J, Motameny S, Thiele H, Becker C, Stemshorn K, Fischer M, Freilinger T, Nürnberg P: Assessing the enrichment performance in targeted resequencing experiments. Hum Mutat. 2012, 33: 635-641., 10.1002/humu.22036

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, : The sequence alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009, 25: 2078-2079., 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352

Nord AS, Lee M, King M, Walsh T: Accurate and exact CNV identification from targeted high-throughput sequence data. BMC Genomics. 2011, 12: 184-, 10.1186/1471-2164-12-184

Knijnenburg J, Oberstein SAJL, Frei K, Lucas T, Gijsbers ACJ, Ruivenkamp CAL, Tanke HJ, Szuhai K: A homozygous deletion of a normal variation locus in a patient with hearing loss from non-consanguineous parents. J Med Genet. 2009, 6: 412-417.

RepeatMasker. [http://repeatmasker.org], []

Verpy E, Leibovici M, Michalski N, Goodyear RJ, Houdon C, Weil D, Richardson GP, Petit C: Stereocilin connects outer hair cell stereocilia to one another and to the tectorial membrane. J Comp Neurol. 2011, 519: 194-210., 10.1002/cne.22509

Zwaenepoel I, Mustapha M, Leibovici M, Verpy E, Goodyear R, Liu XZ, Nouaille S, Nance WE, Kanaan M, Avraham KB, Tekaia F, Loiselet J, Lathrop M, Richardson G, Petit C: Otoancorin, an inner ear protein restricted to the interface between the apical surface of sensory epithelia and their overlying acellular gels, is defective in autosomal recessive deafness DFNB22. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002, 99: 6240-6245., 10.1073/pnas.082515999

Lukashkin AN, Legan PK, Weddell TD, Lukashkina VA, Goodyear RJ, Welstead LJ, Petit C, Russell IJ, Richardson GP: A mouse model for human deafness DFNB22 reveals that hearing impairment is due to a loss of inner hair cell stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012, 109: 19351-19356., 10.1073/pnas.1210159109

Walsh T, Abu Rayan A, Abu Sa’ed J, Shahin H, Shepshelovich J, Lee MK, Hirschberg K, Tekin M, Salhab W, Avraham KB, King M, Kanaan M: Genomic analysis of a heterogeneous Mendelian phenotype: multiple novel alleles for inherited hearing loss in the Palestinian population. Hum Genom. 2006, 2: 203-211.

Shahin H, Walsh T, Rayyan AA, Lee MK, Higgins J, Dickel D, Lewis K, Thompson J, Baker C, Nord AS, Stray S, Gurwitz D, Avraham KB, King M, Kanaan M: Five novel loci for inherited hearing loss mapped by SNP-based homozygosity profiles in Palestinian families. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009, 18: 407-413.

Lee K, Chiu I, Santos-Cortez RLP, Basit S, Khan S, Azeem Z, Andrade PB, Kim SS, Ahmad W, Leal SM: Novel OTOA mutations cause autosomal recessive non-syndromic hearing impairment in Pakistani famlies. Clin Genet. 2013, 84: 294-296., 10.1111/cge.12047

Kurima K, Peters LM, Yang Y, Riazuddin S, Ahmed ZM, Naz S, Arnaud D, Drury S, Mo J, Makishima T, Ghosh M, Menon PSN, Deshmukh D, Oddoux C, Ostrer H, Khan S, Riazuddin S, Deininger PL, Hampton LL, Sullivan SL, Battey JF, Keats BJB, Wilcox ER, Friedman TB, Griffith AJ: Dominant and recessive deafness caused by mutations of a novel gene, TMC1, required for cochlear hair-cell function. Nat Genet. 2002, 30: 277-284., 10.1038/ng842

Hilgert N, Alasti F, Dieltjens N, Pawlik B, Wollnik B, Uyguner O, Delmaghani S, Weil D, Petit C, Danis E, Yang T, Pandelia E, Petersen MB, Goossens D, Favero JD, Sanati MH, Smith R, Van Camp G: Mutation analysis of TMC1 identifies four new mutations and suggests an additional deafness gene at loci DFNA36 and DFNB7/11. Clin Genet. 2008, 74: 223-232., 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01053.x

Gao X, Su Y, Guan L, Yuan Y, Huang S, Lu Y, Wang G, Han M, Yu F, Song Y, Zhu Q, Wu J, Dai P: Novel compound heterozygous TMC1 mutations associated with autosomal recessive hearing loss in a Chinese family. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e63026-, 10.1371/journal.pone.0063026

Sırmacı A, Duman D, Öztürkmen-Akay H, Erbek S, İncesulu A, Öztürk-Hişmi B, Arıcıa ZS, Yüksel-Konuka EB, Taşır-Yılmaze S, Tokgöz-Yılmazf S, Cengiza FB, Aslana İ, Yıldırımg M, Hasanefendioğlu-Bayrakb A, Ayçiçekh A, Yılmazi İ, Fitozj S, Altınk F, Özdağe H, Tekin M: Mutations in TMC1 contribute significantly to nonsyndromic autosomal recessive sensorineural hearing loss: A report of five novel mutations. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009, 73: 699-705., 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.01.005

Vona B, Hofrichter M, Neuner C, Schröder J, Gehrig A, Hennermann JB, Kraus F, Shehata Dieler W, Klopocki E, Nanda I: DFNB16 is a frequent cause of congenital hearing impairment: implementation of STRC mutation analysis in routine diagnostics. Clin Genet. 2014, [Epub ahead of print]

Hoppman N, Aypar U, Brodersen P, Brown N, Wilson J, Babovic-Vuksanovic D: Genetic testing for hearing loss in the United States should include deletion/duplication analysis for the deafness/infertility locus at 15q15. 3. Mol Cytogenet. 2013, 6: 19-, 10.1186/1755-8166-6-19

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIDCD 1F30DC011674 to AES and NIDCD RO1s DC003544, DC002842 and DC012049 to RJHS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Designed study: AES, DLK, HA, RJHS. Performed experiments: KLF, ETC, CJN. Performed analysis: AES, DLK, HA, CMS, CJN, EAB-Z. Collected and assembled data: AES, DLK, KLF, AEW, CJN. Drafted manuscript: AES, RJHS. All authors contributed to, edited and reviewed the final manuscript.

A Eliot Shearer, Diana L Kolbe contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Shearer, A.E., Kolbe, D.L., Azaiez, H. et al. Copy number variants are a common cause of non-syndromic hearing loss. Genome Med 6, 37 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/gm554

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/gm554