Abstract

Background

Discussing patients with cancer in a multidisciplinary team meeting (MDTM) is customary in cancer care worldwide and requires a significant investment in terms of funding and time. Efficient collaboration and communication between healthcare providers in all the specialisms involved is therefore crucial. However, evidence-based criteria that can guarantee high-quality functioning on the part of MDTMs are lacking. In this systematic review, we examine the factors influencing the MDTMs’ efficiency, functioning and quality, and offer recommendations for improvement.

Methods

Relevant studies were identified by searching Medline, EMBASE, and PsycINFO databases (01–01-1990 to 09–11-2021), using different descriptions of ‘MDTM’ and ‘neoplasm’ as search terms. Inclusion criteria were: quality of MDTM, functioning of MDTM, framework and execution of MDTM, decision-making process, education, patient advocacy, patient involvement and evaluation tools. Full text assessment was performed by two individual authors and checked by a third author.

Results

Seventy-four articles met the inclusion criteria and five themes were identified: 1) MDTM characteristics and logistics, 2) team culture, 3) decision making, 4) education, and 5) evaluation and data collection. The quality of MDTMs improves when the meeting is scheduled, structured, prepared and attended by all core members, guided by a qualified chairperson and supported by an administrator. An appropriate amount of time per case needs to be established and streamlining of cases (i.e. discussing a predefined selection of cases rather than discussing every case) might be a way to achieve this. Patient centeredness contributes to correct diagnosis and decision making. While physicians are cautious about patients participating in their own MDTM, the majority of patients report feeling better informed without experiencing increased anxiety. Attendance at MDTMs results in closer working relationships between physicians and provides some medico-legal protection. To ensure well-functioning MDTMs in the future, junior physicians should play a prominent role in the decision-making process. Several evaluation tools have been developed to assess the functioning of MDTMs.

Conclusions

MDTMs would benefit from a more structured meeting, attendance of core members and especially the attending physician, streamlining of cases and structured evaluation. Patient centeredness, personal competences of MDTM participants and education are not given sufficient attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In a context of increasingly complex multidisciplinary cancer treatments and centralisation of cancer care, the role of multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTMs) is growing in importance. In these, usually weekly, meetings, all healthcare providers involved discuss patient cases to formulate the diagnostic or therapeutic strategy [1,2,3,4]. In 1995, the Calman-Hine report set out principles regarding the organisation and structure of high-quality multidisciplinary care [5]. These were further developed by the British National Cancer Action Team in 2010 [5, 6]. MDTMs were set up in accordance with these principles worldwide and today constitute the standard of care [7,8,9,10]. Several national guidelines, as in the Netherlands [11], UK [8, 12], France [13], USA [14] and Australia [15], require discussion of nearly all cancer patients in an MDTM prior to initial treatment, despite a lack of strong evidence supporting survival benefit or improved quality of life for patients [16,17,18]. Worldwide, there are no evidence-based criteria guaranteeing high-quality MDTM functioning. In this review we explore the factors that influence the efficiency, functioning and quality of MDTMs. The impact of MDTMs on clinical outcomes in terms of survival or quality of life is beyond the scope of this review.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review to identify factors that influence the efficiency, performance and quality of MDTMs. Articles written in English and published between 1–1-1990 and 9–11-2021 in the following electronic databases: Medline, Embase, PsychInfo were included. The search terms that were used were different descriptions of ‘oncological multidisciplinary team meeting’ in title or abstract and ‘neoplasm’ as MeSH or Emtree term. The search string is presented in Supplement A. In this generic search string, all articles on oncological MDTMs were collected and checked for eligibility based on the in- and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were: full-text original research articles and any of the following subjects: quality of MDTM, functioning of MDTM, framework and execution of MDTM, decision-making process, education, patient advocacy, patient involvement, and evaluation tools. The exclusion criteria were: no original research article, non-oncological or paediatric MDTMs and articles that fully addressed any of the following topics: impact on patient outcomes or outcomes of the MDTMs regarding medical endpoints (e.g. change of treatment strategy, revised diagnosis), costs of MDTMs, results of MDTMs (e.g. proportion of patients discussed) and implementation of MDTMs.

Title and abstract were independently screened for relevance by two authors (JW and OvdH) based on the in- and exclusion criteria. In cases of discrepancy in judgement, a third author (ID) was consulted. Articles that appeared to meet the research question were assessed by full-text review, again by two authors (JW and OvdH) independently, and checked by a third author (ID). Full-text papers were checked for eligibility and quality. After agreement was reached on the articles to be included, JW extracted the relevant data from these studies and stored this data on the computers of the hospital where the authors work. The extracted data was reviewed by ID. Due to the many different study designs of the included articles, full data coding was not feasible. Therefore the data was classified by an inductive process (JW and ID) into themes and categories, which were examined by OvdH and KvdH. It should be noted that given the lack of formal evidence-based criteria that guarantee high-quality functioning of an MDTM, assumptions were sometimes made (e.g. we assumed that an incomplete team during the MDTM presents a risk for quality).

Results

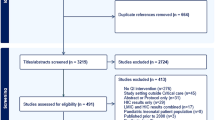

Of an initial number of 4129 articles, 74 met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Five themes with factors influencing functioning were identified: 1) MDTM characteristics and logistics, 2) team culture, 3) decision making, 4) education and 5) evaluation and data collection. Within these five themes a total of 10 subcategories were identified. In Table 1, all included studies are summarised, including the themes and subcategories they cover. In Table 2, recommendations are provided based on the results.

Study selection process. a Case reports, conference abstracts, cancer care, interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary treatment, multidisciplinary team, multidisciplinary management, multidisciplinary recommendation, multidisciplinary clinics, molecular tumour board. b Letters, correspondences, author reply, comments, descriptions, reports, orals, editorials, experiences, perspectives, opinions, study protocols, implementation protocols, overviews, reviews and, systematic reviews. c Subjects were outcomes on survival, diagnostics, pathology reports, radiological information, trial recruitment, comorbidity, adherence to guidelines, and adherence to MDTM recommendation, time to treatment. d Articles about whether or not MDTMs should be implemented in daily practice. e When there was a discrepancy between 2 researchers (OvdH, JW) as to whether or not the article should be included, a third researcher (ID) was consulted. After discussion between the three researchers, the final decision was made. f Four articles published between 1995 and 2005

MDTM characteristics and logistics

Although there is no direct evidence that the quality and functioning of an MDTM is (at least in part) determined by its set-up, it seems clear that a well-organised MTDM is a basic requirement. Reviewing the literature, seven subcategories can be distinguished: 1) schedule, 2) meeting discipline and circumstances, 3) preparation, 4) attendance, 5) patient attendance, 6) cases and streamlining, and 7) administrative support.

Schedule

A factor we identified which impacts on the functioning of MDTMs is a clear meeting schedule with protected time within working hours. In 2013 Ottevanger et al. observed 18 MDTMs in seven Dutch hospitals and interviewed the chairpersons. Adherence to the weekly MDTM schedule was found to be a precondition for an effective MDTM, which was the case in 100% of the tumour-specific MDTMs (n = 14) and in only 40% of the general oncological MDTMs (n = 5) [64]. A survey of 136 surgeons participating in breast cancer MDTMs reported that only 28% of MDTMs were held during regular working hours [59]. A majority of the participants suggested dedicated time for MDTMs during working hours as an improvement [59]. When time for MDTMs is set aside in the participants’ working schedule, their personal contributions to MDTMs improve [31, 51, 56].

Meeting discipline and circumstances

Meeting discipline and interruptions affect the efficacy of MDTMs. Interruptions during MDTMs seem to be common. On average 6 to 11 people were walking in and out of the MDTM and 4 to 6 phone calls disturbed the meeting, according to Ottevanger et al [64].

Structured information presentation, projected clinical imaging results, structured case discussions and written team guidance have been shown to improve ability to reach a multidisciplinary team decision and improves the quality of the information presented [31, 47, 53, 54, 63, 74, 77, 82, 91]. Conference call or video conferencing is becoming the standard of care, as it facilitates the attendance of highly specialised clinicians, minimises travel time and reduces the duration of the diagnostic trajectory [25, 26, 72, 91]. Thirty-six sarcoma MDT members were obliged to participate in completely virtual MDTMs due to the COVID-19 pandemic: 73% were satisfied with the depth of the discussion and 83% felt that decision making had not changed following the switch from face-to-face MDTMs to virtual MDTMS [67]. However, the failure of technological equipment impacts MDTMs negatively [45, 51] and the number of patients discussed per MDTM has been reported as having decreased compared to face-to-face MDTMs [26].

Preparation

Good preparation of an MDTM implies a clear list of patients to be discussed, timely availability of all clinical information including imaging and pathology results, and sufficient time for all core members to prepare their cases [64]. Although an MDTM agenda was nearly always present (93%), a clear presentation of a question to be discussed per patient was available in only half of the meetings (47%) in a MDTM observational study [64]. Time to prepare an MDTM has been suggested as an improvement in several studies [51, 56, 59, 74, 77]. A survey of 292 radiologists found that only 114 respondents (44%) review over 70% of cases prior to the MDTM, mainly due to lack of time [62]. In 5% of the cases discussed at general or tumour-specific MDTMs, pathology or radiology results were absent [64]. Inadequate or absent information about radiology and pathology results proved to be a barrier to making clinical decisions within the MDTM, as was a lack of up-to-date information about the patients’ comorbidities and condition [31, 45, 54, 55, 71, 78, 89]. According to two interview studies, imaging technology and real-time data support and enhance clinical discussion during MDTMs [47, 70].

Attendance

Attendance of core MDT members and a well-functioning chairperson are essential for clinical decision making within the MDTM [31, 55]. Several studies scored the attendance rates of the core MDT members (defined as: surgical oncologist, medical oncologist, radiologist, pathologist, radiation oncologist and an organ-specific specialist) [57, 59, 64, 90]. The results ranged from attendance rates of 49% to over 90% [57, 59, 77]. Several other studies identify non-attendance of core MDT members as a negative factor for efficient decision making during MDTMs [59, 51, 45]. Attendance of the general practitioner (GP) was examined in a semi-structured interview study of 16 Belgian GPs [66]. GPs perceived attendance at an MDTM as part of their work and benefit of the MDTM discussions and the interprofessional collaborative relationships [66]. In an Australian study, a standardised template reporting MDTM findings back to GPs was found to be a feasible alternative [68].

Patients attending MDTMs

A questionnaire completed by 429 breast cancer MDT members and 135 patient advocates was performed by Butow et al [22]. Only 12 health professionals (4%) reported that their work setting allowed patients to attend their MDTM. Patient advocates reported that they were not invited to attend MDTMs and only 47 (35%) was informed when their case was discussed in a MDTM. The common reasons for supporting patient involvement included patients being more informed and empowered, and to facilitate shared decision-making and improve communication between the patient and the medical team [22]. In general, healthcare providers fear attendance would increase anxiety, undermine the doctor-patient relationship (through complex discussions in jargon with different viewpoints put forward by the attending professionals) and have a negative impact on the dynamics of the meeting [22]. The effect of the presence of the patient during the MDTM, including physical examination, did not change the therapeutic decision in a prospective study among 119 head and neck cancer patients [60]. From a patient’s point of view, increased anxiety or depression due to MDTM participation was not noted in most studies, while being better informed and able to present their own preferences were named as advantages [20, 23, 24, 27, 60].

Cases and streamlining

In a prospective observational study of 298 urological cancer patients being discussed in seven MDTMs, cases discussed towards the end of meetings were associated with lower rates of decision-making, information quality and teamworking [55]. In addition, more available time per case was associated with improved teamworking [55]. The amount of time per case differs [35, 61, 91]. For example, an observational study of 10 head and neck cancer MDTMs found that discussion time per patient ranged from 15 s to 8 min, with a mean of 2 min [61].

A Dutch interview study of two collaborating head and neck cancer MDTMs found that only in a minority of discussed cases (8/336) was the additional value of the collaboration acknowledged and the national obligation to discuss all patients was felt to be outdated [43]. The selection of patients to be discussed in an MDTM – nowadays called ‘streamlining’ – was a topic as far back as 1996, when Vetto et al. compared the discussion of all patients in a ‘working conference’ with only discussing ‘fascinating cases’. Of 22 participants surveyed, 77% preferred to discuss all patients [87]. In 2005, a questionnaire involving 136 breast cancer MDT members showed that the selection of cases for discussion was made by the surgeon in 49%, by the medical oncologist in 34%, and by the pathologist in 25% of cases. In half of meetings, all patients were presented [59]. A questionnaire completed by 16 neuro-oncology MDT members reported a mixed response regarding which patients should be discussed: 44% (n = 7) thought all patients should be discussed and 56% (n = 9) thought only those patients with complex management issues should be discussed [34]. A recent national survey of 1220 MDT members in the United Kingdom included a question on how to enhance the effectiveness of MDTMs. They defined streamlining of discussions as follows: ‘specialist time is focused on those cancer cases that don’t follow well-established clinical pathways, with other patients being discussed more briefly’. The majority of participants (69%) agreed that streamlining could allow more straightforward cases to be dealt with more quickly and over half (60%) thought that some form of streamlining would be beneficial for their MDTM, while 25% did not think that streamlining would be beneficial [42].

Administrative support

Support by a coordinator or administrator was available in a minority of oncological MDTMs while a lack of administrative support was found to be a barrier to effective functioning [31, 47, 64, 70]. In a postal survey of breast cancer MDTMs in the UK, 6% of surgeons who responded noted no recording of decisions made in the MDTM [59]. Another survey of 265 MDTM coordinators reported that most of them were trained in data management and IT skills to facilitate MDTMs [44].

Interestingly, where several treatment options for the patient were discussed during an MDTM, only a single option was documented at the end of the discussion [37]. Several studies agreed on the importance of a standardised documentation template and the standard supply of a copy to the general practitioner [33, 34, 68].

Team culture

Attending MDTMs has been reported to result in more interactive and closer working relationships between healthcare professionals of different disciplines [27, 31]. The MDTM process was seen as a peer-review process providing checks and balances and discouraging the conduct of inappropriate or unnecessary investigations. Furthermore, clinicians felt the MDTM provided some medico-legal protection [27, 57]. A focus-group study by Fahim et al. (2020) identified several barriers to team dynamics that negatively affect the decision-making process, including lack of soft skills (effective communication, collaboration), negative group dynamics (bullying), lack of psychological safety (the ability to ask questions or make mistakes), and the presence of participants who dominate the conversation [31]. According to a focus group study with allied health professionals, they often felt inhibited when offering their contribution, despite the fact that they are supposed to supply information about the patients’ condition and preferences. In their experience, there was insufficient time and respect for their information [27]. Some MDTMs were seen as intimidating and part of an ‘boys’ club’. It was easier to contribute when invited by another member of the MDT [27]. Two studies suggested a role for the chairperson in inviting all team members to contribute and arrive at case consensus [35, 51]. The setting of the MDTM has a clear influence on team culture. Face-to-face MDTMs were found to be more informal, spontaneous and conducive to open discussion. In contrast, the videoconferences were formal and regimented, appearing to reflect pre-existing hierarchical positions [26]. An interview study with 22 participants found that video-conferencing has a negative influence on decision making due to poor communication, causing conflicts and friction within the MDT [45]. In contrast, Kunkler et al. reported no differences in Group Behaviour Inventory (GBI) scales between face-to-face and video conferences [50]. Aligning tasks and responsibilities between MDT members is also important. A survey of 58 breast cancer MDT members revealed which expectations each member had regarding their own responsibilities and tasks, and those of other team members, showing discrepancies leading to gaps of information and impaired decision making [48]. The nurse specialist was the least visible of the participants. It was recommended that teams be trained to work together, especially with regard to communication skills, to ensure that patients receive comprehensive and consistent information [48].

Decision making

Two subcategories were identified within the theme of decision making: decision-making process and patient advocacy.

Decision-making process

A qualitative observational study of two centres where 106 cases were discussed analysed the actual decision-making process within the MDTM [12]. They identified different sources of authority that are used to justify actions within discussions: encountered, technological, research evidence, lived experience, interpreter and referral authority. Where there was conflicting authority, encountered authority (authority based on knowing the patient) and clinical experienced authority were decisive in the decision-making process [12]. An interview study involving 179 MDT members found that where opinions were split, in 69% of cases the physician in charge of the patient made the final decision [57]. A smaller study also identified a role for the chairperson in this case [74]. In an interview study of 21 MDT members, 27 barriers were identified that hindered the decision-making process. Most commonly described barriers included gaps in leadership, lack of preparation, unstructured case presentation, individual treatment preferences of treating physicians and prolonged case discussions [31]. They also described 13 facilitators of clinical decision making, including adequate knowledge of guidelines and recent evidence, standardisation of decision making and facilitation of collegiality and teamworking [31]. An observational study noted five ways in which the clinical nurse specialist (CNS) positively contributed to the decision-making process: sharing information, asking questions, providing practical suggestions, framing and using humour [88].

Other identified factors influencing the decision-making process were ‘decision-making fatigue’ during prolonged MDTMs, time-workload pressure, logistic complexity, gender imbalance in the team and negative interactions between team members [80, 81]. ICT tools to support clinical decision making during the MDTM have been developed. In 1295 breast cancer patients a tool of this kind called MATE was found to select up to 61% more cases for clinical trial recruitment and resulted in more concordance with clinical practical guidelines [65].

Patient advocacy

Attending physicians, clinical nurses, patients themselves or patient advocates can represent the patient’s perspective. Clinicians see their role as being an advocate for patients discussed at MDTMs and the absence of the clinician in charge is a negative factor for the functioning of an MDTM [27, 71, 74]. An observational study of 15 MDTMs concluded that individual patient characteristics or patient treatment preferences were rarely considered or discussed and that physicians based their decision making on medical information. In the few cases where patient preferences were raised as a topic, this information did not seem to be taken into account in the decision-making processes [37]. Similar results have been reported, including MDT discussion focusing on the only recommended treatment option, or presenting the treatment option selected within the MDTM as the only option to a patient afterwards, ignoring other equally valid options discussed [20, 39]. When comparing observation with a self-assessment tool, case histories and radiological information were best presented and patients’ views and comorbidities/psychosocial issues were least well presented in a study involving 164 cancer patients and 67 team members in 5 MDTMs [52]. Other studies reported similar findings, all concluding a lack of patient centeredness in terms of available information on comorbidities and preferences [19, 21, 38, 45, 73, 79, 89]. A large survey including 1636 MDT members recommended a crucial role for the CNS in representing patient preferences [56]. A more prominent role for the CNS has also been suggested by others [75, 88]. In an observational study of 171 elderly patients with colorectal cancer a suboptimal decision-making process was observed due to limited use of patient-centered information, such as age-related patient characteristics and preferences [21]. It was found that remarks about general condition in terms of vitality or frailty were significantly more often mentioned during the MDT discussion when a participant with geriatric expertise was present (11% vitality and 19% frailty) compared to an MDTM without geriatric expertise (3% and 8% respectively) [21].

Education

To ensure that MDTMs continue to function well in the near future, it is important to train junior doctors to participate in MDTMs, on the basis of the master and apprentice principle. Up to three quarters of surgeons participating in breast cancer MDTMs saw an educational opportunity for trainees at their MDTMs, according to a survey of Macaskill et al [59]. Eighty-seven percent of 45 neuro-oncology participants agreed that education of fellows, residents and students in MDTMs is a value point [77]. In a survey study including 72 MDTM chairpersons the permission rate to attend the MDTM was 76% for residents and 39% for medical students [28]. An observational study of 52 gynaecological MDTMs noted that fellows and residents were expected to prepare cases in advance to gain a clearer understanding of the subtleties of care from the academic discourse. Educational case discussion focused primarily on treatment options and planning [36]. Junior doctors, trainees and medical students are frequently seated in the outer circle, away from the inner circle where the discussion mostly takes place [47]. Junior physicians were not observed to play a prominent role in the decision-making process and were sometimes asked to perform tasks during the meeting, preventing adequate participation [37, 47, 75]. In four focus groups with 23 participants the educational benefit of attending MDTMs was noted. Nurses and allied health professionals appreciated the opportunity to view pathology and radiology results and achieved a greater understanding of medical care and the decision-making process. Junior medical staff did not participate in the focus groups but were thought to benefit from witnessing decision making by senior staff in determining a treatment plan [27]. Another focus group study with 18 participants recognised the educational benefit of MDTMs in enhancing knowledge or understanding [31]. A Spanish nationwide survey found that in 33 out of 71 MDTMs, educational activities were organised once a year for all MDT members [28].

Evaluation and data collection

Up to nine MDTM evaluation tools aiming to improve the functioning of MDTMs have been identified and are summarised in Table 3. The MDT-MOT tool was originally developed by Lamb et al., [52] and then adapted by Jalil et al., [46] Shah et al., [76] and Harris et al [41]. Table 3 shows this together. Most of these tools only score items that have been reported to be essential for a well-functioning MDTM [5, 6]. In seven of the nine tools predefined items were scored by an observer [40, 41, 46, 49, 52, 76, 84], while two tools are a self-assessment measure [29, 85]. The categories scored are most commonly the more practical items such as attendance, availability of all patient data, and organisation and administration of the MDTM. Six tools evaluate the performance of the chairperson [29, 40, 41, 46, 49, 76] and three tools evaluate the team culture [40, 41, 85]. Personal development and training are explicitly scored in the tool of Harris et al. [40]. and mentioned in the self-assessment tool of Taylor et al [85]. The perspectives and preferences of the patient are explored in the tools of Evans et al. [29] Jalil et al. [46] Shah et al. [76] and Taylor et al [84]. The education and training function of MDTMs is explored in four tools [29, 40, 84, 85] The tool of Evans et al. is the only one that measures communication with the general practitioner [29]. In this tool a ‘maturity score’ of the MDT was determined on the basis of five domains based on self-assessment [29]. In a follow-up study, results from three years of self-assessment (2017–2019) of 12 MDTs were compared; in nine out of 17 questions a significant improvement was observed. Highly significant improvements were seen for documenting consensus, developing terms of reference, referring to clinical practical guidelines, and establishing referral criteria. There was no significant change for questions related to patient considerations, professional development and quality improvement activities [30]. In a before and after study design, the implementation of up to five interventions to optimise decision making (use of discussion tools, workshops, MDT or chairperson training, audit and feedback) was evaluated using two of the mentioned tools (MTB-MODe and MDT-OARS). Four MDTs were evaluated before and after the implementation of a mean of three interventions. The quality of the per-case decision making did not improve significantly (P = 0.78) [32]. The tools MDT-OARS and TEAM were further developed into the ‘MDT feedback for improving teamwork (MDT-FIT)’ programme and implemented in 10 breast cancer MDTMs in the UK. This programme consists of 3 stages (set-up, assessment, feedback including actions for improvement) and lasts for 8–12 weeks. Within 36 interviews the acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility of MDT-FIT was found to be moderate to high [86]. Results of MDT-FIT are lacking. Several other studies evaluated the quality of teamworking by using the MTB-MODe tool and found this manner of direct observation feasible and reliable [35, 58]. In summary, there are several feasible evaluation tools available that are useful in guiding the evaluation process, however none of them have yet proven to optimise MTDM functioning. In MDTMs, structured and multidisciplinary data is collected, which can be used to further improve care and to evaluate an MDTM’s own functioning. In 15 semi-structured interviews, participants were unanimous that data collection during MDTMs was important and should be enabled by health information systems. They also expressed concerns about the quality of data that was currently collected through MDTMs [47]. A study that evaluated a self-assessment tool concluded that nine out of 117 respondents confirmed that internal audits were performed to assess whether treatment decision making made in the MDTM was in line with current best practices [29]. Robinson et al. performed an ethnographic study on engaging MDTMs in translational research and quality improvement and found that the capture of real-time data was a priority in helping involve teams more actively in quality-improvement activities [70]. A mixed method survey, interview and observational study on the impact of data collection in three lung cancer MDTMs found that data regarding number of cases, stage, final diagnosis and time to diagnosis and treatment was collected. This data was found to be easy to interpret and relevant for both clinical practice and the MDTM [83].

Discussion

This extensive systematic literature review identified five themes (MDTM characteristics and logistics, team culture, decision making, education and evaluation and data collection) that are important for an efficient, well-functioning and high quality MDTM and results in feasible recommendations (Table 2). A clear and structured meeting schedule is a prerequisite, attendance of all core MDTM members mandatory, as well as sufficient preparation time, especially for radiologists and pathologists, if review of the investigations is desired. Clear formulation of the question to be answered may be helpful in the decision-making process. Technical and administrative support, the latter not only for preparation but also for reporting, is a boundary condition. A regular evaluation based on plan/do/check/act is necessary to see if all goals have been met. Small adjustments to improve these elements can already result in a significant improvement in the quality of MDTMs. Team skills, such as effective communication and collaboration are important, therefore team training is suggested [31]. We did not identify any literature regarding personal competences or skills and their impact in the functioning or quality of MDTMs.

Although MDTMs are organised in the interests of patients, the latter are seldom present at the meeting where their case is discussed. In general, healthcare providers take a cautious attitude to patient participation. They fear it may cause anxiety and undermine the doctor-patient relationship, and some doctors do not want to confront patients with conflicting opinions about the best treatment [20, 22, 27, 60]. For some patients it might be disappointing to witness their cancer diagnosis, which turned their lives upside-down, being discussed in only a few minutes. On the other hand, the majority of patients report feeling better informed without suffering increased anxiety [22,23,24] Massoubre et al. compared therapeutic decision-making in the MDTM following discussion of a patient file, or after patient participation in the MDTM, and found a concordance rate of 97% [60]. They concluded that the patient’s presence was not essential, provided the medical file was complete and current. An advantage of the absence of the patient was that it decreased the duration of the meeting [60]. On the basis of the literature, it is impossible to provide a definitive recommendation. Nevertheless, it remains an important issue. Well defined studies are needed to answer these questions.

MDTMs are currently under pressure due to the increasing number of patients that need to be discussed in relatively little time [4]. Streamlining of cases can reduce the pressure on MDTMs. A distinction can be made between standard and complex cases: only complex cases would be discussed in the MDTM while standard cases would be handled on the basis of predetermined guidelines/algorithms [92, 93]. Support for streamlining varied considerably in the different studies we identified [34, 42, 43, 87]. Considering the MDTM as a means of medico-legal protection might give cause for hesitation [27, 57]. Another disadvantage of case selection is the lack of opportunity to use the MDTM as source for collecting patient data for research or quality improvement purposes [29, 47, 70, 83]. However, we believe that given the context of increasing cancer incidence and prevalence, and the development of more complex and new multidisciplinary treatment options, streamlining is inevitable in the near future. That said, further research on patient case selection is needed and alternative methods of data collection must be explored.

In COVID-19 times, MDTMs came under pressure due to a high working load of most MDT members, the emotional impact of COVID-19 care on health care professionals, decreased availability of diagnostic and treatment facilities and simply restrictions in the number of persons allowed in rooms or accelerated turning to digital MDTMs. Despite this, team skills seemed not to be much affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, since the depth of discussions did not change following the switch from face-to-face MDTMs to virtual MDTMs [67]. Furthermore, Grosclaude et al. (2020) measured the MDTM activity of 191 different French MDTMs in the period of January 2019 – April 2020 and found only a moderate decrease of 8% less meetings during this period, which reflects the commitment of these teams to MDTMs [94]. The decision-making process in MDTMs is influenced by a large number of factors. Knowing the patient, clinical experience and leadership contribute most to actual decision-making [12, 27, 31, 57, 71, 74]. Patients presented in the MDTM by their attending physician were up to 20% more likely to receive a correct diagnosis [95]. Remarkedly, multiple studies have found a lack of patient centeredness in the MDTM (i.e. insufficient knowledge of patient preferences and comorbidities during the discussion) [19,20,21, 27, 37,38,39, 45, 52, 59, 71, 73, 79, 89]. A crucial role was seen for the CNS in representing patient preferences [56, 75, 88]. Further steps are needed to improve the patient centeredness of MDTMs, for example explicit mention of patient preferences in the registration form or introduction of a dedicated representative (i.e. attending physician or CNS) who participates in the MDTM. Although we realize that being able to have a patient representative present for every patient case has many practical challenges.

The NCAT 2010 guidelines state ‘There is a teaching and training role for MDTs both within the team itself (e.g. bringing patient cases back) and beyond (e.g. for clinicians in training)’ [6]. Although the educational function of an MDTM has been acknowledged [27, 31, 59, 77], implementation in practice seems to be difficult. Junior doctors do not have an active role within the MDTM. For them the process was believed to be passive: mainly observation of decision-making by the senior staff [27, 31, 36, 37, 47, 75]. The focus of the learning process was on medical competences. No literature was found on the educational function of the MDTM for junior doctors, as well as core members, regarding other competences such as collaboration and communication. In any event it is important to state whether education of junior staff is also the aim of the MDTMs. In that case education tools have to be well-defined and incorporated in the evaluation cycle.

Many tools have been developed to evaluate the functioning of MDTMs. Most of these tools are used by an observer who scores the predefined (predominantly practical) items during an MDTM. The feasibility of the MTB-MODe, MDT-OARS and TEAM tools as well as the MDT-FIT programme has been demonstrated but their impact on improving the functioning of MDTMs remains unclear.

Future developments to further improve the quality of MDTMs include the use of computerised clinical support systems (CDSSs), which implement patient data, make guidelines-based treatment recommendations or identify patients eligible for clinical trials [93, 96, 97].

Strengths and limitations

Our systematic review has several strengths. Two independent authors meticulously searched over 4,700 articles, and a third author was included in the event of conflicting judgements. This article therefore presents a complete overview of known factors influencing the quality and functioning of MDTMs and makes recommendations on optimising MDTMs for healthcare providers. Due to the heterogeneity of studies that we reviewed, a fully methodological review according to the PRISMA guidelines [98] was not feasible. However, all full text articles have been reviewed for both relevance and quality by three independent researchers (JW, OvdH, ID) as good as possible. Furthermore, on account of the lack of formal evidence-based criteria guaranteeing high-quality MDTM functioning, assumptions have sometimes been made. The study period spans three decades. Some results from older literature (e.g. ICT problems) may no longer be a problem at this point in most countries. However, it does reflect the conditions that a high-quality MDTMs must meet. In order to obtain a complete overview of all literature on the optimal functioning of MDTMs, an inclusion date from 1990 has been chosen, as that was the time when MDTMs were first introduced in cancer care. However, we realize that some items have been resolved, and new ones, for example the enormous number of patients to be discussed, became more important.

Conclusion

In this systematic review we show that, in addition to a more structured meeting and the presence of all MDTM core members, there should be sufficient discussion time for all cases with more emphasis on patient centeredness. Streamlining of cases and training the MDT could be the way to achieve this.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information file.

References

Wright FC, De Vito C, Langer B, Hunter A. Multidisciplinary cancer conferences: a systematic review and development of practice standards. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(6):1002–10.

Gouveia J, Coleman MP, Haward R, Zanetti R, Hakama M, Borras JM, et al. Improving cancer control in the European Union: conclusions from the Lisbon round-table under the Portuguese EU Presidency, 2007. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(10):1457–62.

Ouwens M, Hulscher M, Hermens R, Faber M, Marres H, Wollersheim H, et al. Implementation of integrated care for patients with cancer: a systematic review of interventions and effects. Int J Qual Health Care. 2009;21(2):137–44.

Soukup T, Lamb BW, Arora S, Darzi A, Sevdalis N, Green JS. Successful strategies in implementing a multidisciplinary team working in the care of patients with cancer: an overview and synthesis of the available literature. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2018;11:49–61.

Health Do. A policy framework for commissioning cancer services: a report by the Expert Advisory Group on Cancer to the Chief Medical Officers of England and Wales. BMJ. 1995;310:1425. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.310.6992.1425.

NHS-National-Cancer-Action-Team. The Characteristics of an Effective multidisciplinary Team (MDT). www.ncin.org.uk/cancer_type_and_topic_specific_work/multidisciplinary_teams/mdt_development 2010.

Borras JM, Albreht T, Audisio R, Briers E, Casali P, Esperou H, et al. Policy statement on multidisciplinary cancer care. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(3):475–80.

Griffith C, Turner J. United Kingdom National Health Service, Cancer Services Collaborative “Improvement Partnership”, Redesign of Cancer Services: A National Approach. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30(Suppl 1):1–86.

Juan A, Berlanga P, Bisogno G, Michon J, Valteau-Couanet D, Kearns P, et al. Paediatric tumour boards in Europe: Current situation and results of an international survey in expo-r-net. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:S152.

El Saghir NS, Keating NL, Carlson RW, Khoury KE, Fallowfield L. Tumor boards: optimizing the structure and improving efficiency of multidisciplinary management of patients with cancer worldwide. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2014:e461–6.

SONCOS normeringrapport 6; Multidisciplinaire oncologische zorg in Nederland. 2018.

Dew K, Stubbe M, Signal L, Stairmand J, Dennett E, Koea J, et al. Cancer care decision making in multidisciplinary meetings. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(3):397–407.

Cannell E. The French Cancer Plan: an update. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(10):738.

American college of surgeons C, IL. Commission on Cancer. Cancer Program Standards 2012, Ensuring patient-centered care. 2012.

Victorian cancer plan 2016–2020; Improving cancer outcomes for all Victorians: www.healthvic.gov.au/cancer.

Pillay B, Wootten AC, Crowe H, Corcoran N, Tran B, Bowden P, et al. The impact of multidisciplinary team meetings on patient assessment, management and outcomes in oncology settings: A systematic review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;42:56–72.

Bydder S, Nowak A, Marion K, Phillips M, Atun R. The impact of case discussion at a multidisciplinary team meeting on the treatment and survival of patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Intern Med J. 2009;39(12):838–41.

MacDermid E, Hooton G, MacDonald M, McKay G, Grose D, Mohammed N, et al. Improving patient survival with the colorectal cancer multi-disciplinary team. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11(3):291–5.

Bate J, Wingrove J, Donkin A, Taylor R, Whelan J. Patient perspectives on a national multidisciplinary team meeting for a rare cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2019;28(2): e12971.

Bohmeier B, Schellenberger B, Diekmann A, Ernstmann N, Ansmann L, Heuser C. Opportunities and limitations of shared decision making in multidisciplinary tumor conferences with patient participation - A qualitative interview study with providers. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(4):792–9.

Bolle S, Smets EMA, Hamaker ME, Loos EF, van Weert JCM. Medical decision making for older patients during multidisciplinary oncology team meetings. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(1):74–83.

Butow P, Harrison JD, Choy ET, Young JM, Spillane A, Evans A. Health professional and consumer views on involving breast cancer patients in the multidisciplinary discussion of their disease and treatment plan. Cancer. 2007;110(9):1937–44.

Chaillou D, Mortuaire G, Deken-Delannoy V, Rysman B, Chevalier D, Mouawad F. Presence in head and neck cancer multidisciplinary team meeting: The patient’s experience and satisfaction. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2019;136(2):75–82.

Choy ET, Chiu A, Butow P, Young J, Spillane A. A pilot study to evaluate the impact of involving breast cancer patients in the multidisciplinary discussion of their disease and treatment plan. Breast. 2007;16(2):178–89.

Davison AG, Eraut CD, Haque AS, Doffman S, Tanqueray A, Trask CW, et al. Telemedicine for multidisciplinary lung cancer meetings. J Telemed Telecare. 2004;10(3):140–3.

Delaney G, Jacob S, Iedema R, Winters M, Barton M. Comparison of face-to-face and videoconferenced multidisciplinary clinical meetings. Australas Radiol. 2004;48(4):487–92.

Devitt B, Philip J, McLachlan SA. Team dynamics, decision making, and attitudes toward multidisciplinary cancer meetings: Health professionals’ perspectives. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6(6):e17–20.

Díez JJ, Galofré JC, Oleaga A, Grande E, Mitjavila M, Moreno P. Results of a nationwide survey on multidisciplinary teams on thyroid cancer in Spain. Clin Transl Oncol. 2019;21(10):1319–26.

Evans L, Donovan B, Liu Y, Shaw T, Harnett P. A tool to improve the performance of multidisciplinary teams in cancer care. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8(2): e000435.

Evans L, Liu Y, Donovan B, Kwan T, Byth K, Harnett P. Improving Cancer MDT performance in Western Sydney - three years’ experience. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):203.

Fahim C, Acai A, McConnell MM, Wright FC, Sonnadara RR, Simunovic M. Use of the theoretical domains framework and behaviour change wheel to develop a novel intervention to improve the quality of multidisciplinary cancer conference decision-making. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):578.

Fahim C, McConnell MM, Wright FC, Sonnadara RR, Simunovic M. Use of the KT-MCC strategy to improve the quality of decision making for multidisciplinary cancer conferences: a pilot study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):579.

Farrugia DJ, Fischer TD, Delitto D, Spiguel LRP, Shaw CM. Improved breast cancer care quality metrics after implementation of a standardized tumor board documentation template. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(5):421–3.

Field KM, Rosenthal MA, Dimou J, Fleet M, Gibbs P, Drummond K. Communication in and clinician satisfaction with multidisciplinary team meetings in neuro-oncology. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17(9):1130–5.

Gandamihardja TAK, Soukup T, McInerney S, Green JSA, Sevdalis N. Analysing Breast Cancer Multidisciplinary Patient Management: A Prospective Observational Evaluation of Team Clinical Decision-Making. World J Surg. 2019;43(2):559–66.

Gatcliffe TA, Coleman RL. Tumor board: More than treatment planning - A 1-year prospective survey. J Cancer Educ. 2008;23(4):235–7.

Hahlweg P, Hoffmann J, Harter M, Frosch DL, Elwyn G, Scholl I. In Absentia: An Exploratory Study of How Patients Are Considered in Multidisciplinary Cancer Team Meetings. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10): e0139921.

Hahlweg P, Didi S, Kriston L, Harter M, Nestoriuc Y, Scholl I. Process quality of decision-making in multidisciplinary cancer team meetings: a structured observational study. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):772.

Hamilton DW, Heaven B, Thomson RG, Wilson JA, Exley C. Multidisciplinary team decision-making in cancer and the absent patient: A qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e012559. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012559.

Harris J, Green JSA, Sevdalis N, Taylor C. Using peer observers to assess the quality of cancer multidisciplinary team meetings: A qualitative proof of concept study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014;7:355–63.

Harris J, Taylor C, Sevdalis N, Jalil R, Green JSA. Development and testing of the cancer multidisciplinary team meeting observational tool (MDT-MOT). Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(3):332–8.

Hoinville L, Taylor C, Zasada M, Warner R, Pottle E, Green J. Improving the effectiveness of cancer multidisciplinary team meetings: analysis of a national survey of MDT members’ opinions about streamlining patient discussions. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8(2): e000631.

van Huizen LS, Dijkstra P, Halmos GB, van den Hoek JGM, van der Laan KT, Wijers OB, et al. Does multidisciplinary videoconferencing between a head-and-neck cancer centre and its partner hospital add value to their patient care and decision-making? A mixed-method evaluation. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11): e028609.

Jalil R, Lamb B, Russ S, Sevdalis N, Green JS. The cancer multi-disciplinary team from the coordinators’ perspective: results from a national survey in the UK. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:457.

Jalil R, Ahmed M, Green JS, Sevdalis N. Factors that can make an impact on decision-making and decision implementation in cancer multidisciplinary teams: an interview study of the provider perspective. Int J Surg. 2013;11(5):389–94.

Jalil R, Akhter W, Lamb BW, Taylor C, Harris J, Green JS, et al. Validation of team performance assessment of multidisciplinary tumor boards. J Urol. 2014;192(3):891–8.

Janssen A, Robinson T, Brunner M, Harnett P, Museth KE, Shaw T. Multidisciplinary teams and ICT: a qualitative study exploring the use of technology and its impact on multidisciplinary team meetings. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):444.

Jenkins VA, Fallowfield LJ, Poole K. Are members of multidisciplinary teams in breast cancer aware of each other’s informational roles? Qual Health Care. 2001;10(2):70–5.

Johnson CE, Slavova-Azmanova N, Saunders C. Development of a peer-review framework for cancer multidisciplinary meetings. Intern Med J. 2017;47(5):529–35.

Kunkler I, Fielding G, Macnab M, Swann S, Brebner J, Prescott R, et al. Group dynamics in telemedicine-delivered and standard multidisciplinary team meetings: Results from the TELEMAM randomised trial. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(Suppl 3):55–8.

Lamb BW, Sevdalis N, Arora S, Pinto A, Vincent C, Green JS. Teamwork and team decision-making at multidisciplinary cancer conferences: barriers, facilitators, and opportunities for improvement. World J Surg. 2011;35(9):1970–6.

Lamb BW, Sevdalis N, Mostafid H, Vincent C, Green JS. Quality improvement in multidisciplinary cancer teams: an investigation of teamwork and clinical decision-making and cross-validation of assessments. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(13):3535–43.

Lamb BW, Sevdalis N, Vincent C, Green JS. Development and evaluation of a checklist to support decision making in cancer multidisciplinary team meetings: MDT-QuIC. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(6):1759–65.

Lamb BW, Green JSA, Benn J, Brown KF, Vincent CA, Sevdalis N. Improving decision making in multidisciplinary tumor boards: Prospective longitudinal evaluation of a multicomponent intervention for 1,421 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(3):412–20.

Lamb BW, Sevdalis N, Benn J, Vincent C, Green JS. Multidisciplinary cancer team meeting structure and treatment decisions: a prospective correlational study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(3):715–22.

Lamb BW, Taylor C, Lamb JN, Strickland SL, Vincent C, Green JS, et al. Facilitators and barriers to teamworking and patient centeredness in multidisciplinary cancer teams: findings of a national study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(5):1408–16.

Lee YG, Oh S, Kimm H, Koo DH, Kim DY, Kim BS, et al. Practice Patterns Regarding Multidisciplinary Cancer Management and Suggestions for Further Refinement: Results from a National Survey in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49(4):1164–9.

Lumenta DB, Sendlhofer G, Pregartner G, Hart M, Tiefenbacher P, Kamolz LP, et al. Quality of teamwork in multidisciplinary cancer team meetings: A feasibility study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2): e0212556.

Macaskill EJ, Thrush S, Walker EM, Dixon JM. Surgeons' views on multi-disciplinary breast meetings. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(7):905–8.

Massoubre J, Lapeyre M, Pastourel R, Dupuch V, Biau J, Dillies AF, et al. Will the presence of the patient at multidisciplinary meetings influence the decision in head and neck oncology management? Acta Otolaryngol. 2018;138(2):185–9.

Mullan BJ, Brown JS, Lowe D, Rogers SN, Shaw RJ. Analysis of time taken to discuss new patients with head and neck cancer in multidisciplinary team meetings. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;52(2):128–33.

Neri E, Gabelloni M, Bäuerle T, Beets-Tan R, Caruso D, D’Anastasi M, et al. Involvement of radiologists in oncologic multidisciplinary team meetings: an international survey by the European Society of Oncologic Imaging. Eur Radiol. 2021;31(2):983–91.

Oeser A, Gaebel J, Dietz A, Wiegand S, Oeltze-Jafra S. Information architecture for a patient-specific dashboard in head and neck tumor boards. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2018;13(8):1283–90.

Ottevanger N, Hilbink M, Weenk M, Janssen R, Vrijmoeth T, de Vries A, et al. Oncologic multidisciplinary team meetings: evaluation of quality criteria. J Eval Clin Pract. 2013;19(6):1035–43.

Patkar V, Acosta D, Davidson T, Jones A, Fox J, Keshtgar M. Using computerised decision support to improve compliance of cancer multidisciplinary meetings with evidence-based guidance. BMJ Open. 2012;2(3):e000439. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000439.

Pype P, Mertens F, Belche J, Duchesnes C, Kohn L, Sercu M, et al. Experiences of hospital-based multidisciplinary team meetings in oncology: An interview study among participating general practitioners. Eur J Gen Pract. 2017;23(1):155–63.

Rajasekaran RB, Whitwell D, Cosker TDA, Gibbons C, Carr A. Will virtual multidisciplinary team meetings become the norm for musculoskeletal oncology care following the COVID-19 pandemic? - experience from a tertiary sarcoma centre. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):18.

Rankin NM, Collett GK, Brown CM, Shaw TJ, White KM, Beale PJ, et al. Implementation of a lung cancer multidisciplinary team standardised template for reporting to general practitioners: a mixed-method study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12): e018629.

Rankin NM, Lai M, Miller D, Beale P, Spigelman A, Prest G, et al. Cancer multidisciplinary team meetings in practice: Results from a multi-institutional quantitative survey and implications for policy change. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2018;14(1):74–83

Robinson TE, Janssen A, Harnett P, Museth KE, Provan PJ, Hills DJ, et al. Embedding continuous quality improvement processes in multidisciplinary teams in cancer care: exploring the boundaries between quality and implementation science. Aust Health Rev. 2017;41(3):291–6.

Rosell L, Alexandersson N, Hagberg O, Nilbert M. Benefits, barriers and opinions on multidisciplinary team meetings: a survey in Swedish cancer care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):249.

Salami AC, Barden GM, Castillo DL, Hanna M, Petersen NJ, Davila JA, et al. Establishment of a regional virtual tumor board program to improve the process of care for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(1):E66–74.

Salloch S, Ritter P, Wascher S, Vollmann J, Schildmann J. Medical expertise and patient involvement: a multiperspective qualitative observation study of the patient’s role in oncological decision making. Oncologist. 2014;19(6):654–60.

Sarkar S, Arora S, Lamb BW, Green JSA, Sevdalis N, Darzi A. Case review in urology multidisciplinary team meetings: What members think of its functioning. Journal of Clinical Urology. 2014;7(6):394–402.

Scott R, Hawarden A, Russell B, Edmondson RJ. Decision-Making in Gynaecological Oncology Multidisciplinary Team Meetings: A Cross-Sectional, Observational Study of Ovarian Cancer Cases. Oncol Res Treat. 2020;43(3):70–7.

Shah S, Arora S, Atkin G, Glynne-Jones R, Mathur P, Darzi A, et al. Decision-making in Colorectal Cancer Tumor Board meetings: Results of a prospective observational assessment. Surg Endosc Other Interv Tech. 2014;28(10):2783–8.

Snyder J, Schultz L, Walbert T. The role of tumor board conferences in neuro-oncology: a nationwide provider survey. J Neurooncol. 2017;133(1):1–7.

Soukup T, Petrides KV, Lamb BW, Sarkar S, Arora S, Shah S, et al. The anatomy of clinical decision-making in multidisciplinary cancer meetings: A cross-sectional observational study of teams in a natural context. Medicine. 2016;95(24): e3885.

Soukup T, Lamb BW, Sarkar S, Arora S, Shah S, Darzi A, et al. Predictors of Treatment Decisions in Multidisciplinary Oncology Meetings: A Quantitative Observational Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(13):4410–7.

Soukup T, Gandamihardja TAK, McInerney S, Green JSA, Sevdalis N. Do multidisciplinary cancer care teams suffer decision-making fatigue: an observational, longitudinal team improvement study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5): e027303.

Soukup T, Lamb BW, Morbi A, Shah NJ, Bali A, Asher V, et al. A multicentre cross-sectional observational study of cancer multidisciplinary teams: Analysis of team decision making. Cancer Med. 2020;9(19):7083–99.

Stone E, Rankin N, Phillips J, Fong K, Currow DC, Miller A, et al. Consensus minimum data set for lung cancer multidisciplinary teams: Results of a Delphi process. Respirology. 2018;23(10):927–34.

Stone E, Rankin NM, Vinod SK, Nagarajah M, Donnelly C, Currow DC, et al. Clinical impact of data feedback at lung cancer multidisciplinary team meetings: A mixed methods study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2020;16(1):45–55.

Taylor C, Atkins L, Richardson A, Tarrant R, Ramirez AJ. Measuring the quality of MDT working: an observational approach. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:202.

Taylor C, Brown K, Lamb B, Harris J, Sevdalis N, Green JS. Developing and testing TEAM (Team Evaluation and Assessment Measure), a self-assessment tool to improve cancer multidisciplinary teamwork. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(13):4019–27.

Taylor C, Harris J, Stenner K, Sevdalis N, Green SAJ. A multi-method evaluation of the implementation of a cancer teamwork assessment and feedback improvement programme (MDT-FIT) across a large integrated cancer system. Cancer Med. 2021;10(4):1240–52.

Vetto JT, Richert-Boe K, Desler M, DuFrain L, Hagen H. Tumor board formats: “fascinating case” versus “working conference.” J Cancer Educ. 1996;11(2):84–8.

Wallace I, Barratt H, Harvey S, Raine R. The impact of Clinical Nurse Specialists on the decision making process in cancer multidisciplinary team meetings: A qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2019;43: 101674.

Wihl J, Rosell L, Carlsson T, Kinhult S, Lindell G, Nilbert M. Medical and Nonmedical Information during Multidisciplinary Team Meetings in Cancer Care. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(1):1008–16.

Wright FC, Lookhong N, Urbach D, Davis D, McLeod RS, Gagliardi AR. Multidisciplinary cancer conferences: identifying opportunities to promote implementation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(10):2731–7.

Yuan Y, Ye J, Ren Y, Dai W, Peng J, Cai S, et al. The efficiency of electronic list-based multidisciplinary team meetings in management of gastrointestinal malignancy: a single-center experience in Southern China. World J Surg Onc. 2018;16(1):146.

Soukup T, Lamb BW, Sevdalis N, Green JS. Streamlining cancer multidisciplinary team meetings: challenges and solutions. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2020;81(3):1–6.

Winters DA, Soukup T, Sevdalis N, Green JSA, Lamb BW. The cancer multidisciplinary team meeting: in need of change? History, challenges and future perspectives. BJU Int. 2021;128(3):271–9.

Grosclaude P, Azria D, Guimbaud R, Thibault S, Daubisse-Marliac L, Cartron G, et al. COVID-19 impact on the cancer care structuration: Example of the multidisciplinary team meeting dedicated to oncology in Occitanie. Bull Cancer. 2020;107(7–8):730–7.

Basta YL, Baur OL, van Dieren S, Klinkenbijl JHG, Fockens P, Tytgat KMAJ. Is there a Benefit of Multidisciplinary Cancer Team Meetings for Patients with Gastrointestinal Malignancies? Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(8):2430–7.

Klarenbeek SE, Weekenstroo HHA, Sedelaar JPM, Fütterer JJ, Prokop M, Tummers M. The Effect of Higher Level Computerized Clinical Decision Support Systems on Oncology Care: A Systematic Review. Cancers. 2020;12(4):1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12041032.

Pasetto S, Gatenby RA, Enderling H. Bayesian framework to augment tumor board decision making. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2021;5:508–17.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7): e1000097.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported on in this paper.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W. identified the research question, the in- and exclusion criteria and the search string, which were corrected and checked by O.vd.H., I.D., V.L. and R.V.. J.W and O.vd.H. independently screened title and abstract based on the in- en exclusion criteria. In cases of discrepancy in judgement I.D. was consulted. Full-text review was independently conducted by J.W. and O.vd.H., and checked by I.D.. By an inductive process themes were identified by J.W. and I.D., and examined by O.vd.H. and K.vd.H.. J.W. and I.D. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:

Supplement A – Full description on the executed search

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Walraven, J.E.W., van der Hel, O.L., van der Hoeven, J.J.M. et al. Factors influencing the quality and functioning of oncological multidisciplinary team meetings: results of a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 22, 829 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08112-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08112-0