Abstract

Background

To identify the strategies and contextual factors that enable optimal engagement of patients in the design, delivery, and evaluation of health services.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane, Scopus, PsychINFO, Social Science Abstracts, EBSCO, and ISI Web of Science from 1990 to 2016 for empirical studies addressing the active participation of patients, caregivers, or families in the design, delivery and evaluation of health services to improve quality of care. Thematic analysis was used to identify (1) strategies and contextual factors that enable optimal engagement of patients, (2) outcomes of patient engagement, and (3) patients’ experiences of being engaged.

Results

Forty-eight studies were included. Strategies and contextual factors that enable patient engagement were thematically grouped and related to techniques to enhance design, recruitment, involvement and leadership action, and those aimed to creating a receptive context. Reported outcomes ranged from educational or tool development and informed policy or planning documents (discrete products) to enhanced care processes or service delivery and governance (care process or structural outcomes). The level of engagement appears to influence the outcomes of service redesign—discrete products largely derived from low-level engagement (consultative unidirectional feedback)—whereas care process or structural outcomes mainly derived from high-level engagement (co-design or partnership strategies). A minority of studies formally evaluated patients’ experiences of the engagement process (n = 12; 25%). While most experiences were positive—increased self-esteem, feeling empowered, or independent—some patients sought greater involvement and felt that their involvement was important but tokenistic, especially when their requests were denied or decisions had already been made.

Conclusions

Patient engagement can inform patient and provider education and policies, as well as enhance service delivery and governance. Additional evidence is needed to understand patients’ experiences of the engagement process and whether these outcomes translate into improved quality of care.

Registration

N/A (data extraction completed prior to registration on PROSPERO).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Patient engagement has become a cornerstone of quality of care [1,2,3,4,5,6] and is a frequently stated goal for healthcare organizations. Traditionally, and most commonly, this engagement has focused on the relationship between patients and providers in making care decisions or how to improve patient efforts to manage their own care [7]. However, there are growing efforts to integrate patients in broader ways, including efforts to improve or redesign service delivery by incorporating patient experiences [8,9,10,11,12]. These efforts are due in part to an increased recognition and acceptance that users of health services have a rightful role, the requisite expertise, and an important contribution in the design and delivery of services [4]. While the nature of patient engagement may vary from including patients as members of a board to time-limited consultation with patients on service redesign, its aims are consistent—to improve the quality of care [11, 13, 14].

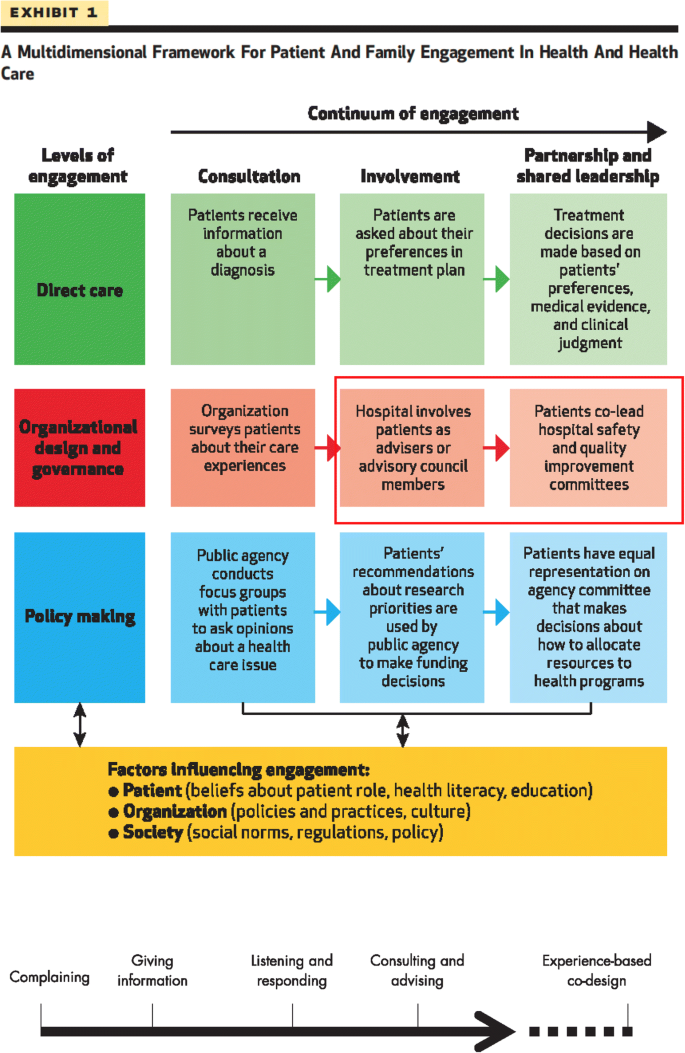

Healthcare organizations have a long tradition of measuring the experience of patients, and health service “users” including families, caregivers, and clients, with their services. Yet, traditional satisfaction surveys often prove difficult to translate into improved service delivery [15, 16]. Indeed, research on patient engagement has pointed to the importance of augmenting traditional surveys and complaint processes, moving towards fuller engagement of patients in reviewing and improving the quality of service delivery in institutions and in the community [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. This recognition has been accompanied by a growth in the development of instruments to measure and improve the quality of care patients receive. Over the past two decades, assessments of quality of care from the patient perspective have shifted from patient satisfaction to patient experiences [26]. Increasing literature indicates that it is not only feasible to involve patients in the delivery or re-design of health care [9] but that such engagement can lead to reduced hospital admissions [27], improved effectiveness, efficiency and quality of health services [28,29,30,31], improved quality of life, and enhanced quality and accountability of health services [9]. Frameworks of patient involvement have been developed that move from the traditional view of the patient as a passive recipient of a service to an integral member of teams re-designing health care [8, 11]. For example, one framework developed by Bate and Robert (2006) describes a continuum of patient involvement, which ranges from complaints, giving information, listening, and consulting towards experience-based co-design of services [8]. Low-level engagement, such as consulting, comprises largely unidirectional feedback (e.g., focus groups, surveys, interviews), whereas high-level engagement, like co-design, represents a partnership in the design or evaluation of services. A more recent framework developed by Carman et al. describes various levels of engaging patients and families in health and health care, from consultation or involvement to partnership and shared leadership in various activities including direct care, organizational design, and governance to policy-making [11]. Carman’s continuum of engagement was influenced by Arnstein’s formative “ladder of citizen participation,” a continuum of public participation in governance ranging from limited participation to a state of collaborative partnership in which citizens share leadership or control decisions [32].

Governments and health care institutions are urged by some experts to engage patients and other service users, including caregivers and relatives in more robust ways [8, 33] where patients are actively involved as partners or co-leads in organizational re-design and evaluation of health care delivery, as depicted by the red section in Carman’s framework (Fig. 1). Despite the substantive body of research on strategies to engage patients and their effects on patients and health services, the literature is dispersed and has not been recently synthesized into a coherent overview. If the benefits of engaging patients in the design or delivery of health care are to be realized at an organization or system level, then effective strategies and the contextual factors enabling their outcomes need to be identified so that learning can be generalized. We conducted a systematic review of international English language literature on strategies for actively engaging patients and families in improving or redesigning health care and the contextual factors influencing the outcomes of these efforts. The explicit questions that guided our review were:

-

1.

What are the strategies and contextual factors that enable optimal engagement of patients in the design, delivery, and evaluation of health services?

-

2.

What are the outcomes of patient engagement on services?

-

3.

What are patients’ experiences of being engaged?

Methods

Approach

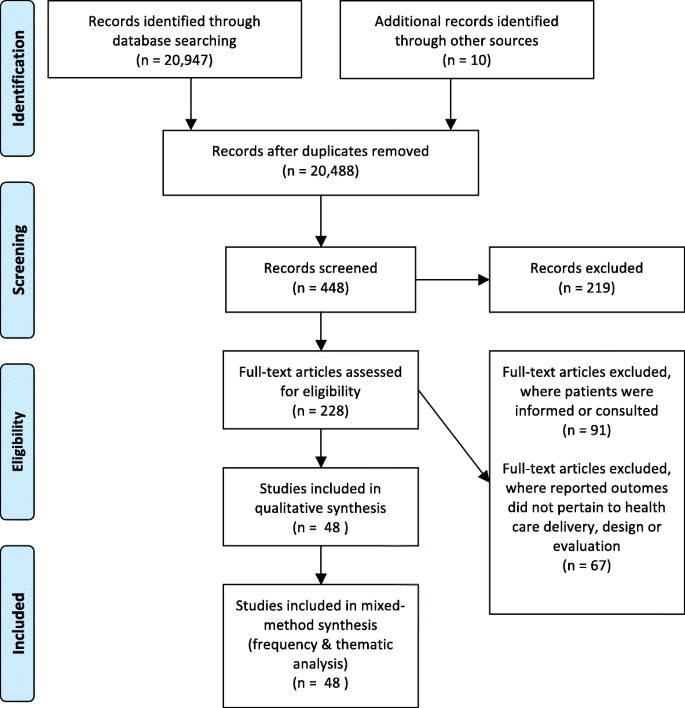

We took a comprehensive approach in our systematic search and included all empirical qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods study designs across all settings of care to address our narrow research questions. Our review did not fit into typologies of literature reviews [34, 35], given that we included qualitative and quantitative studies (to capture the breadth of studies in this area), employed a thematic analysis (given the multiplicity of designs), and applied a quality appraisal. We followed the PRISMA reporting criteria for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (Fig. 2) [36].

Flow diagram for search and selection process. From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6 (6): e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Search strategy

In accordance with the core principles of systematic review methodology [37], we conducted a systematic review of relevant literature with the help of a librarian using the electronic databases of: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library, Scopus, PsychINFO, Social Science Abstracts, AbiInform Business Source Premier (EBSCO), and ISI Web of Science. We searched the databases using the following subject headings related to patient engagement—combinations of “patient”, “user”, “client”, “caregiver”, “family” and “engage*”, “participat*”, “involve*”, “consult*”; for those related to designing, evaluating and delivery of services—combinations of “design”, “deliver*”, “evaluat*”, “outcome”, “develop*”, “plan*” and “health services”, “health care”, “health”, “service”. We included a combination of search terms from each category for each search, for example, “patient” AND “engage*” AND “design” AND “health services”).

Criteria for selection

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were available empirical articles that explicitly investigated the participation of patients, caregivers, or families in the design, delivery, and evaluation of health services, which aligns with involving or partnering/sharing leadership with patients in organizational design and governance, reflecting Carman’s framework (Fig. 1) [11]. Searches were restricted to qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods articles published in English between January 1990 and March 2016. We chose 1990 as this coincided with the emergence of patient engagement particularly in mental health services and the broader quality of care discourse. All settings of care were eligible. We excluded articles that did not explicitly address patient engagement, as well as those that did not pertain to the broader design, delivery, and evaluation of health services (e.g., directly engaging patients in patient safety activities such as challenging staff who treat them to wash their hands or monitor the use of a safety checklist in their care, or in their self-management or treatment decisions, or studies pertaining to patient involvement in health research, community development, or health promotion). We also excluded articles that did not describe the outcome of the engagement of patients and those in which the outcomes did nor pertain to the design, delivery, or evaluation of health services (e.g., those that related to developing questionnaires or conceptual frameworks, insights on how to engage patients or work collaboratively). We focused on studies that consulted, involved, partnered, or co-designed health services with patients, informed by Bate and Robert’s [8] and Carman et al.’s [11] frameworks on patient engagement (Fig. 1). Finally, theoretical or conceptual articles as well as those focused on guideline development, instrument development, or broader organizational issues were excluded.

Titles and abstracts of the papers were examined to decide if the full article should be retrieved (Fig. 2). EO and CF were the primary reviewers who examined the titles and abstracts, applied inclusion criteria to the articles, and abstracted the data using an abstraction form. Any disagreement and uncertainties regarding inclusion were discussed and agreed upon by an additional reviewer (YB) on the abstraction form. We conducted calibration exercises to ensure reliability in applying the selection criteria. Reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts, and discrepancies were discussed and reviewed by the third reviewer. There was a 95.46% observed agreement and 85.75% expected agreement between primary reviewers, with a kappa statistic of 0.703 (standard error, 0.021; 95% confidence interval, 0.662–0.744), which is relatively high compared to other knowledge synthesis protocols reporting 50% consistency rates [34].

Data abstraction and synthesis

Data abstraction forms were used to describe the studies’ population, location (i.e., country), goals, methodology, and outcomes (Table 1); contextual factors influencing engagement (i.e., leadership and specific barriers and facilitators to patient engagement) (Table 2); and patients’ experience with the engagement and evaluation of study quality (Tables 2 and 3). Studies were then categorized by the level of patient engagement using Bate and Robert’s (2006) continuum of patient involvement [8]. Consistent with our aims to review strategies for actively engaging patients and families in improving or redesigning health care, we focused on studies using co-design or those consulting patients but also using elements of co-design—i.e., the more active levels of engagement on the Bates and Robert continuum. We classified changes or products of engaging patients as “quality of care outcomes” and the impact of the engagement on patients as “patients experience outcomes” (Table 1). Quality of care outcomes were categorized into one of the following: developing education or a service-related tool, informing policy or planning documents, and enhancing services or governance. Study quality was assessed by one person and two verifiers using a quality appraisal tool that systematically reviews disparate forms of evidence and methodologies on a scale from “very poor,” “poor,” “fair,” and “good” [38], which reflected the mixed methods articles in our review. Verification involved systematically checking and confirming the fit between each criterion of the assessment tool and the conceptual work of analysis and interpretation of study quality among a subset of studies. We also assessed the possible impact of study quality on the review’s findings (akin to a “sensitivity analysis” conducted for meta-analyses).

Data analysis

Data were analyzed to address the three research questions, with the intention of (1) identifying strategies and contextual factors that enable optimal engagement of patients in the design, delivery, and evaluation of health services; (2) identifying the outcomes of patient engagement; and (3) exploring patients’ experiences of being engaged. YB analyzed the data using quantitative (i.e., frequency analysis) and qualitative methods. YB used thematic analysis to identify the strategies and contextual factors (i.e., barriers and facilitators), outcomes, and experiences of optimal patient engagement. This process involved identifying prominent or recurring themes in the literature (relevant to our research questions) and summarizing the findings of different studies under thematic headings using summary tables. A coding framework was developed to thematically describe the strategies and contextual factors enabling patient engagement. YB and RB refined the framework as new data emerged during the analysis.

Results

Included studies

We found a total of 20,957 studies about involving patients in the design, delivery, or evaluation of health care. Of these, we excluded 20,909 because they did not report outcomes related to health care delivery, design, or evaluation (n = 67) or only informed/consulted with patients, as opposed to engage them in co-design (n = 91) (Fig. 2; Additional file 1: Table S3 & Additional file 2: Figure S1). Our final sample of studies included 48 papers involving patients, families, and caregivers along with service users, health care providers, staff, board members, health care managers, administrators, and decision-makers (Table 1). The publication date of the included studies spanned from 1993 to 2016, and interestingly, co-design was employed as early as 1993 to as recently as 2015 in published studies. Of the 48 included studies, 27 were qualitative studies; 3 were quantitative; 13 constituted mixed methods studies, which included qualitative, quantitative methods; and 5 comprised user panels or advisory meetings (Table 4). We restricted our analysis to articles actively engaging patients. Half of the articles (n = 24) included consultative activities typical of low-level engagement (i.e., where patients provided input on research design or measures as part of the research or administrative team). The other half were co-design (high-level engagement—i.e., deliberative, reflexive processes where patients and providers work together to create solutions [39]) (Table 4). Engagement efforts spanned a range of services, including pediatrics, community and primary care, and most frequently occurred in mental health services (n = 17; 35%—Tables 4 and 1). Studies originated from various countries, with most deriving from the UK (n = 26; 54%) (Tables 4 and 1). Few studies formally evaluated patients’ experiences of the process of being engaged (n = 12; 25%) (Additional file 3: Table S1).

Strategies for optimal patient engagement to improve quality of care

We identified various strategies that contributed to optimal patient engagement, which were mediated by key contextual factors that enabled or constrained the effectiveness of the engagement. These strategies were thematically grouped as techniques to enhance (1) design, (2) recruitment, (3) involvement, (4) creating a receptive context, and (5) leadership actions. Here, we describe the strategies and contextual factors that enabled optimal patient engagement (see also Additional file 3: Table S1).

Techniques to enhance design of engagement

In designing engagements, several studies pointed to the importance of clarifying the objectives, roles, and expectations of the engagement for patients/carers [40,41,42,43,44,45]. Approaches that gave users specific roles or engaged them in a formal structure such as a steering committee [45] or that enabled patients to set the agenda, develop shared mission and purpose statements and participate in all/most stages of the planning, administration, and evaluation made participants feel comfortable with the team and process, maintained patient involvement throughout the course of the process, and improved the quality of outcomes [41, 45,46,47,48,49,50]. These techniques occurred in mental health, HIV, and pediatric service settings where patients were engaged to improve access to, and quality of, care or promote a culture change in the development and delivery of services.

An important strategy used in pediatric, diabetes, and home care settings was holding training sessions to prepare staff and patients, which provided clarity on roles and responsibilities, helped patients or carers understand how they could best contribute, sensitized participants to the contextual and cultural issues, and increased patients’ confidence and commitment to the engagement process [41, 51, 52]. Training also offered the benefit of building positive relationships between users, facilitators, and staff [43, 45, 49, 53, 54], which also served to mediate a key barrier identified: providers’ skepticism towards engaging patients and devolving power to them [42, 55]. Therefore, these techniques helped to create a level playing field and support staff in their efforts to be partners.

Techniques to enhance representation

With respect to sampling and recruitment, several studies stressed the importance of ensuring diversity and representation consistent with the broader population across different professional backgrounds and skills [43, 45, 54]. These studies endorsed recruiting patients through providers, [42] existing patients [56], and those with broader networks or previous working relationships with staff [45, 54, 57, 58]. These techniques proved useful in engaging patients in the context of HIV/AIDS prevention, interventions to reduce repetition of self-harm and substance use, and identifying barriers to mental health services [42, 56,57,58]. One caveat with this approach is that it needs to be weighed against the potential for introducing biases or including self-selected participants. Offering stipends, financial compensation (e.g., child care, transportation), or other incentives encouraged participation [42, 45, 50, 54, 55, 58, 59]. One study in the HIV setting used creative techniques to incentivize participation beyond monetary incentives, such as counseling, access to medical care, and granting diplomas [58].

Techniques to enhance involvement

Several authors also endorsed flexible approaches for involving patients [45, 49, 53, 54]. For example, Gibson et al. [60] used peer reporter interviews (where patient pairs interviewed each other), headline generation (where phrases were created to capture important issues), group discussion (using a Who, Why, When, What, How structure), a written exercise, and questionnaires for non-attendees to find out what youth would like from their follow-up pediatric oncology services. Other techniques identified in studies were the inclusion of higher proportions of patients compared to providers or staff to give patients a stronger voice in the discussion and process [61] and building in debriefing to provide feedback on how suggestions were acted upon to increase the accuracy of the findings and offer an opportunity for additional input. These techniques proved useful in engaging patients to prioritize stroke service issues and document the process of change of a mental health organization [62, 63]. Others built in regular updates to patient support group to elicit more views, thereby broadening the reach and involvement of patients and providing opportunities to raise and discuss issues of concern in informal settings [48, 54]. One creative technique was a buddy system for users/families to ensure their participation at meetings and throughout implementation/evaluation of a quality improvement project in mental health services [44].

Techniques to create a receptive context

Several studies across general medicine, diabetes, mental health, and emergency services highlighted the importance of creating a receptive context by giving each of the stakeholder groups equal say, using techniques such as deliberation and democratic dialog, [39, 51] values and beliefs exercise [48], and narratives to facilitate shared understandings, generate consensus, or find common ground [54, 64]. These techniques created a level playing field and supported staff in their efforts to be partners. Other studies focused on the empowerment and autonomy of users through “active citizenship” in an “egalitarian spirit” [50, 65] which was found to foster a culture of respect [54]. Ensuring that users had an equal voice throughout all aspects of building the intervention was found to help equalize the power differential that often arises in professionally delivered services [65]. Finally, location influenced participation—some studies held consultation outside of the hospital setting such as a disco to appeal to youth [66]. Others conducted meetings in participants’ homes [58] and childcare community sites [67].

External facilitation [39, 63] catalyzed receptive contexts that encouraged user involvement by creating a positive working environment with mutual respect and equal partnership [53]. Finally, attention was also paid to the physical environment (e.g., cleanliness, chair arrangement [53]) and use of physical props, and visual mapping, which supported participants’ discussion and interactions as well as demonstrated to service users the importance of their contribution [68].

Leadership actions

A key facilitator of successful engagement was actions and involvement by organizational leaders. This occurred in a variety of ways including top-down approaches and at community levels where local champions led initiatives or were actively engaged to ensure their success. Top-down approaches included institutional- or executive-level commitment and sponsorship, which was readily apparent across mental health, HIV, and pediatric care settings [41, 44,45,46, 50, 63]. Having managers and executives recognize and advocate for the importance of patient involvement fostered a sense of empowerment and commitment among patients and ensured organizational sustainability of the engagement. This was a goal of two mental health studies, where the senior level of a local authority took a “top-down” approach to promote user involvement, which resulted in a reported culture change throughout the authority [40, 63]. This was highlighted in one study’s “ideological and policy commitment to meaningful involvement of people affected with HIV” as demonstrated by ongoing contact with management and executives and a head clinician open to changes that would disturb traditional relationships and power disparities between service users and providers [50]. Leadership action was also shown to help align the engagement findings or recommendations and ensure that they are advanced within the organization’s relevant strategic plans and policies in primary care [69]. Timing is also an important factor—ensuring that the engagement occurs prior to decision-making, rather than providing input on proposals to which services are already committed was stressed in a number of studies [45]. Otherwise, the engagement could run the risk of being perceived as tokenistic by the users.

Outcomes of engaging patients to improve quality of care

Discrete outcomes of improved quality of care

Most studies noted more than one type of outcome on the quality of care, including enhanced care or service delivery (n = 35), development of specific policy or planning documents (n = 15), and enhanced governance and education or tool development (n = 5 and 11, respectively). Examples of educational materials, tools, policy, and planning documents included evaluation tools [49], electronic personal health records for mental health users [70], a new tool for discharge [71], creation of models of care [72], and organization priorities and processes [49]. Examples of care process, service delivery, and governance included the creation of a prevention of delirium program [73], family integrated program in NICU [45], and care pathway for cellulitis that reduced admissions to hospital [48]. Other engagements in this category led to complete organizational redesign of an outpatient HIV clinic in Southern Norway [50], reconceptualized service for outpatients [68], and revisions to the delineation of roles and responsibilities between an Aboriginal community-controlled health service and local Australian health service [74].

We conceptualized the development of educational materials, tools, policy, and planning documents as “discrete products,” whereas enhanced care process, service delivery, and governance constituted “care process or structural outcomes.” Interestingly, discrete products were more likely to derive from studies using lower levels of engagement (i.e., mostly consultative with elements of co-design), while care process or structural outcomes were more likely to result from higher levels of engagement (i.e., co-design) (Table 3).

Impact of engaging patients on the institution

Engaging patients can also change the culture of staff and care settings. The experiences reported in these articles included shifts in organizational culture promoting further patient participation in service design and delivery, [40, 63, 75] achieving collaboration and mutual learning, [42, 47, 76, 77] and sharing or neutralizing power among patients and providers or staff, [52] as well as developing new competencies and negotiating for service changes [39, 59] (Table 4). Interestingly, these outcomes tended to arise in mental health settings and from co-design engagements (Table 5). Further analysis of the methods used in these studies revealed key enabling factors including creating deliberative spaces to share experiences, including external facilitation; broadening power and control to include users, values, and beliefs exercises; conducting user/staff/provider training; and implementing a top-down approach from the local authority (Table 5).

Patients’ experiences of being engaged to improve quality of care

Twenty-three of the 48 studies provided information on the patients’ experiences of their engagement, though only 12 studies formally evaluated patients’ experiences in the process of being engaged to improve quality of care. Of those that evaluated experiences, ten studies reported positive views, while in two studies, patients reported negative experiences and two studies reported both positive and negative experiences (Additional file 3: Table S1). Of the positive experiences, patients and carers expressed satisfaction with the engagement processes [43, 78] were interested in continuing their involvement in the longer term, [75] felt the experience to be educational, [52] and felt that participation highlighted issues that would have otherwise been ignored [39, 64, 75]. Positive experiences were linked to feeling empowered and independent as a result of skills development and positive recognition [58, 59, 63]. Some patients reported increased self-esteem from contributing [41, 58, 66] and improved self-efficacy and self-sufficiency [76] and that the experience encouraged peer educators to pursue formal training [55]. In another study, staff reported learning about user participation [46].

Patient feedback in other engagement studies was not as positive. Some studies found that patients were satisfied but felt the engagement demanded considerable energy and time [66]. Others felt that their involvement was tokenistic because decisions had been made in advance or was used to justify decisions that had already been made [47, 61]. Some participants felt that their requests were denied or that managerial support was lacking [47], while others were dissatisfied with their lack of involvement in analyzing the findings and creating the final report [46].

Quality appraisal

The average quality of the studies was “fair,” based on a quality appraisal tool that systematically reviews disparate forms of evidence and methodologies on a scale from “very poor,” “poor,” “fair,” and “good” [38] (Additional file 4: Table S2). We also assessed the possible impact of study quality on the review’s findings (akin to a “sensitivity analysis” conducted for meta-analyses). There were only 6 (of 48) “poor” quality studies. Removing the six poor quality studies reduced the number/range of examples provided for our findings on the strategies/contextual factors that contributed to optimal patient engagement (research question 1), their outcomes on services (research question 2), and patients’ experience of being engaged (research question 3), but deletion of these studies from the analysis did not alter the substance of the findings.

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive review of the strategies used to engage patients in service planning, design, and evaluation. It also identifies the outcomes and contextual factors shaping optimal patient engagement to improve quality of care. Strategies and contextual factors that enabled patient engagement included techniques to enhance design, recruitment, involvement, and leadership action, and those aimed at creating a receptive context. Reported outcomes ranged from developing education or tools for patients and providers and informing policy or planning documents (discrete products) to enhanced care, service delivery, and governance (care process or structural outcomes). Interestingly, the level of engagement appears to influence the outcomes of service redesign: discrete products largely derived from low-level (consultative) engagement, whereas care process or structural outcomes mainly derived from high-level (co-design) engagement. Surprisingly, only a minority of studies (n = 12; 25%) formally evaluated patients’ experiences of the engagement activities. While most experiences were positive, some patients sought greater involvement and felt that their involvement was important but tokenistic, especially when requests were denied or when the engagement was used to justify decisions that had already been made. However, it remains unclear how these initiatives affect patients and whether these improvements translate into improved quality of care at a system level.

There were several limitations to this review. Despite the large number of initial search results, there was only a small number of studies focused on involving patients in co-designing health service improvement. Therefore, despite our best attempts, the specificity of our search criteria was modest, a problem familiar to systematic reviews in health services research, which typically crosses many disciplinary boundaries [38]. Future searches would benefit from improved keywords or MeSH terms on the topic of patient engagement. In addition, studies characterized health service users and their involvement differently, ranging from user-centeredness, patient-centered care, and user involvement to patient involvement or participation. Indeed, “user” was a common term used in the UK, whereas other terms such as “patient” and “caregiver” are commonly used in the USA and Canada. These different conceptualizations might signify important distinctions, and the use of different terms, and the publication of these papers across many different journals, raises challenges in identifying and analyzing this literature. We addressed this limitation by using multiple terms and search strategies across multiple disciplinary databases that incorporated terms used in similar reviews. We deliberately sought out the terminology used in key articles to expand our search though may not have captured the entire breadth of terms, such as “consumer,” a popular term used in Australian health services research. We echo previous work that identified this “conceptual muddle” as “one of the greatest barriers to truly integrating patient involvement into health services, policy, and research” [79].

There was also significant variation in sample sizes and populations included in these engagement studies. Samples sizes ranged from 3 to 372 participants and included a variety of patients, families, caregivers, service users, health care providers, staff, board members, health care managers, administrators, and decision-makers. Many studies did not provide details on their sample. These variations illuminate the absence of a standard approach for designing and reporting engagement initiatives. This variation may also reflect the variety of journals in which this research is reported. Additional limitations include the variety of methods used and the limited evaluation of the engagement methods themselves. Where there was no explicit evaluation of engagement, other information including authors’ discussion of strengths and limitations was used to assess the effectiveness of engagement. However, this does not specifically comprise evaluation of the engagement process or its outcomes on care. Development of evaluative metrics and frameworks for the procedural and substantive outcomes of engagements appears warranted. A final important limitation is that our search ended in 2016, and therefore, these insights may differ in the future given the rapidly growing field of patient engagement. This is a limitation familiar to systematic reviews but a future review may be warranted.

Despite these limitations, our study revealed key insights into the factors that influence the ability of health care organizations and decision-makers to create opportunities for engagement that are not provided in individual studies, which cross disciplines and geographical boundaries. We found that successful patient engagement resulted in culture change within the organization, meaningful collaboration and mutual learning, and shared or neutralized power, which tended to arise in settings where co-design is used. Optimal engagement often includes some of the following strategies: use of deliberative spaces to share experiences, external facilitation, broadening power and control to include users in all aspects of the process, flexible approaches for involving users, user training, clarity of roles and objectives, providing feedback, leadership by local champions and securing institutional and/or executive level commitment, and sponsorship from local authority by way of dedicated resources and on-going contact with management and executives. Leadership is key, but there may be a potential temporal trend in leadership actions; top-down approaches to patient engagement tended to be reported in earlier studies [40, 63] whereas more clinician or community-driven initiatives emerged from more recent studies [42, 77]. Another important factor is the timing of engagement. If the engagement occurred after a decision had been made, the success (or even function) of the engagement became highly questionable from the patient’s perspective. Taken together, this analysis suggests that co-design methods supported by executive sponsorship or driven by local champions that use externally facilitated, deliberative, experience-based discourse with trained users can promote successful patient engagement and outcomes.

Mental health settings emerged as a frequent venue for patient engagement in our review. The earliest reports in our review [61, 63, 80] are in this setting, suggesting that the therapeutic approaches, the nature of the population, or the orientation of mental health services might encourage greater patient participation in this area. Indeed, enabling service user involvement in care planning is a key principle of contemporary mental health guidance in the UK [81] and a potentially effective method of improving the culture and responsiveness of mental health services in light of a service history founded on aspects of containment and compulsion, and the stigmatization of those using mental health services [82]. Many of the co-design engagement activities that led to staff and organizational changes such as improved collaboration and mutual learning [42, 47, 76, 77], sharing or neutralizing power among patients and providers or staff [52], developing new competencies, and negotiating for service changes [39, 59] also occurred in mental health. While patient engagement is now occurring in many settings, the experiences in mental health settings serve as important examples of effective patient engagement.

Ultimately, the effectiveness of any patient engagement should be judged by its impact on patient care. There is a growing body of literature that indicates that engaging patients can lead to improved effectiveness, efficiency, quality of care [28,29,30,31], health outcomes, and cost-effective health service utilization [27, 83, 84]. The outcomes reported in our review spanned beyond improved care to include enhanced governance and informed policies and organizational planning, which illustrates the breadth of quality of care initiatives that might be sought through patient engagement. However, drawing causal associations between engaging patients in health services improvement and health outcomes is difficult. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether these improvements translate into sustained or improved quality of care beyond local settings at a system level. Indeed, one study found a lack of evidence that patient involvement leads to the implementation of patient-centered care [85]. Some evaluative tools are emerging [86], yet more studies are needed that assess the conditions on which these tools and strategies can sustain the quality of care systemically.

Our review builds upon previous reviews in this field by providing insight into the associations between quality improvement methods and the varying system-level outcomes they yield. Indeed, our review echoes previous research indicating that patient engagement can lead to a multiplicity of health services outcomes with sufficient role definition, training, and alignment of patient-provider expectations but that the quality of the reporting has been poor and the full impact of patient engagement is not fully understood [87,88,89]. Previous reviews have been limited to specific countries [87], care settings (e.g., mental health [89]), hospitals [90], or study design (e.g., qualitative studies [88]). In this way, our review provides a comprehensive perspective of optimal strategies used internationally, across care settings and using multiple methodologies to engage patients, caregivers, and relatives in quality of care improvement initiatives. Our review also provides novel insights into how the level of engagement influences the outcomes, namely, discrete products (e.g., development of tools and documents) largely derived from low-level engagement (consultative unidirectional feedback), whereas care process or structural outcomes (e.g., improved governance, care or services) mainly derived from high-level engagement (co-design or partnership strategies). If the benefits of engaging patients in the design or delivery of health care are to be realized at an organization or system level, then effective strategies and the contextual factors enabling their outcomes need to be identified so that learning can be generalized. Importantly, our review provides guidance on the effective strategies and contextual factors that enable patient engagement including techniques to enhance the design, recruitment, involvement, and leadership action, and those aimed to create a receptive context.

Future research would benefit from greater consistency in the conceptual, methodological, and evaluative frameworks employed. Greater emphasis is also needed on a procedural evaluation that assesses group composition, group cohesion or collaboration, equality of the participation, and the level of deliberation/reasoning. Such assessments are being developed in the deliberative democracy field [91] and could be informative in patient engagement initiatives. The limited evaluation of patients’ experiences is particularly ironic given the intent of these services to be patient-centered. Additional evaluative metrics should be developed to examine patients’ experiences. Finally, since it is difficult to draw causal relationships between patient engagement and health outcomes, future research should incorporate longitudinal measures and approaches to explore the impact of patient co-design on quality of care.

Several practice implications also emerge and reflect factors linked to the success of quality improvement initiatives more generally. Senior leadership support is critical to success since it increases the likelihood that the relevant decision-makers will implement the findings, and dedicated resources may encourage staff commitment to these efforts.

Conclusions

Despite the substantive body of research on strategies to engage patients and their effects on patients and health services, the literature is varied and dispersed. This study provides a comprehensive review of the strategies used to engage patients in service planning and design, identifies the outcomes, and contextual factors shaping optimal patient engagement to improve quality of care. Patient engagement can inform education, tools, planning, and policy (discrete products) as well as enhance service delivery and governance (care process or structural outcomes). The level of engagement appears to influence the outcomes of service redesign; discrete products are largely derived from low-level (consultative to co-design) engagement, whereas care process or structural outcomes mainly derived from high-level (co-design) engagement. Further evidence is needed to understand patients’ experiences of the engagement process and whether these outcomes translate into improved quality of care.

References

Darzi A. High quality care for all: our journey so far. London: Department of Health; 2008.

Ontario Health Quality Council. QMonitor: 2009 report on Ontari’s health system. Toronto: Government of Ontario; 2009.

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2001.

Bradshaw PL. Service user involvement in the NHS in England: genuine user participation or a dogma-driven folly? J Nurs Manag. 2008;16(6):673–81.

Say RE, Thomson R. The importance of patient preferences in treatment decisions—challenges for doctors. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):542–5.

Coulter A. What do patients and the public want from primary care? BMJ. 2005;331(7526):1199–201.

Coulter A, Ellins J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ. 2007;335(7609):24–7.

Bate P, Robert G. Experience-based design: from redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(5):307–10.

Crawford MJ, Rutter D, Manley C, Weaver T, Bhui K, Fulop N, et al. Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. BMJ. 2002;325(7375):1263.

Johnson B, Abraham M, Conway J, Simmons L, Edgman-Levitan S, Sodomka P, et al. Partnering with patients and families to design a patient- and family-centered health care system. Bethesda: Institute of Family-Centered Care; 2008.

Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, Sofaer S, Adams K, Bechtel C, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff. 2013;32(2):223–31.

Boivin A, Lehoux P, Lacombe R, Burgers J, Grol R. Involving patients in setting priorities for healthcare improvement: a cluster randomized trial. Implement Sci. 2014;9:24.

Parand A, Dopson S, Renz A, Vincent C. The role of hospital managers in quality and patient safety: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2014;4(9):e005055.

Pomey MP, Flora L, Karazivan P, Dumez V, Lebel P, Vanier MC, et al. The Montreal model: the challenges of a partnership relationship between patients and healthcare professionals. Sante Publique. 2015;27(1 Suppl):S41–50.

Nelson EC, Batalden PB. Patient-based quality measurement systems. Qual Manag Health Care. 1993;2(1):18–30.

Nelson EC, Wasson JH. Using patient based information to rapidly redesign care. Healthc Forum J. 1994;37(4):25–9.

DLB S. Engaging patients as vigilant partners in aafety a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67(2):119–48.

Uding N, Kieckhefer G, Trams C. Parent and community participation in program design. Clin Nurs Res. 2009;18(1):68–79.

Vincent CA, Coulter A. Patient safety: what about the patient? Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11(1):76–80.

Cornwell J. Exploring how to improve patients’ experience in hospital at both national and local levels. Nurs Times. 2009;105:26.

Coulter A, Elwyn G. What do patients want from high-quality general practice and how do we involve them in improvement? Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:22–5.

Hibbard JH. Engaging health care consumers to improve the quality of care. Med Care. 2003;41(1):61–70.

Conway J, Johnson B, Edgman-Levitan S, Schlucter J. Partnering with patients and families to design a patient and family centred health care system: a roadmap for the future—a work in progress. Bethesda: Institute for Family Centered Care; 2006.

Pomey M-P, Pierre M, Veronique G. La participation des usagers à la gestion de la qualité des CSSS : un mirage ou une réalité ? La revue de l’innovation : La Revue de l’innovation dans le secteur. Publica. 2009;14(2):1–23.

Goodrich J, Cornwell J. Seeing the person in the patient: the point of care review paper. The King’s Fund: London; 2008.

Elwyn G, Buetow S, Hibbard J, Wensing M. Measuring quality through performance. Respecting the subjective: quality measurement from the patient’s perspective. BMJ. 2007;335(7628):1021–2.

Simpson EL, House AO. Involving users in the delivery and evaluation of mental health services: systematic review. BMJ. 2002;325(7375):1265.

Favod J. Taking back control... giving patients information about their drug regimes improves compliance. Nurs Times. 1993;89:68–70.

Sheppard M. Client satisfaction, extended intervention and interpersonal skills in community mental health. J Adv Nurs. 1993;18(2):246–59.

Beech P, Norman IJ. Patients’ perceptions of the quality of psychiatric nursing care: findings from a small-scale descriptive study. J Clin Nurs. 1995;4(2):117–23.

Connor H. Collaboration or chaos: a consumer perspective. Aust N Z J Ment Health Nurs. 1999;8(3):79–85.

Arnstein SR. A ladder of citizen participation. J Am Plan Assoc. 1969;35(4):216–24.

Berwick DM. What patient centered care should mean: confessions of an extremist. Health Aff. 2009;28(4):555–65.

Kastner M, Tricco AC, Soobiah C, Lillie E, Perrier L, Horsley T, et al. What is the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to conduct a review? Protocol for a scoping review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:114.

Pare G, Trudel MC, Jaana M, Kitsiou S. Synthesizing information systems knowledge: a typology of literature reviews. Inf Manage. 2015;52(2):183–99.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–12.

Lavis J, Davies H, Oxman A, Denis JL, Golden-Biddle K, Ferlie E. Towards systematic reviews that inform health care management and policy-making. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(Suppl 1):35–48.

Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(9):1284–99.

Iedema R, Merrick E, Piper D, Britton K, Gray J, Verma R, Manning N. Codesigning as a discursive practice in emergency health services: the architecture of deliberation. J Appl Behav Sci. 2010;46(1):73–91.

Barnes M, Wistow G. Achieving a strategy for user involvement in community care. Health Social Care. 1994;2:347–56.

Coad J, Flay J, Aspinall M, Bilverstone B, Coxhead E, Hones B. Evaluating the impact of involving young people in developing children’s services in an acute hospital trust. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(23):3115–22.

Frazier SL, Addul-Adil J, Atikins MS, Gathright T, Jackson M. Can’t have one without the other: mental health providers and community parents reducing barriers to services for families in urban poverty. J Community Psychol. 2007;35(4):435–46.

Lofters A, Virani T, Grewal G, Lobb R. Using knowledge exchange to build and sustain community support to reduce cancer screening inequities. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2015;9(3):379–87.

Murphy L, Wells JS, Lachman P, Bergin MA. Quality improvement initiative in community mental health in the Republic of Ireland. Health Sci J. 2015;9(13):1–11.

Macdonell K, Christie K, Robson K, Pytlik K, Lee SK, O'Brien K. Implementing family-integrated care in the NICU: engaging veteran parents in program design and delivery. Adv Neonatal Care. 2013;13(4):262–9. quiz 70-1

Weinstein J. Involving mental health service users in quality assurance. Health Expect. 2006;9(2):98–109.

Todd S, Felce D, Beyer S, Shearn J, Perry J, Kilsby M. Strategic planning and progress under the All Wales Strategy: reflecting the perceptions of stakeholders. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2000;44(Pt 1):31–44.

Elwell R. Developing a nurse-led integrated ‘red legs’ service. Br J Community Nurs. 2014;19(1):12. 4-9

Tooke J. Involving people with dementia in the work of an organisation: service user review panels. Qual Ageing Older Adults. 2013;14(1):56–65.

Berg RC, Gamst A, Said M, Aas KB, Songe SH, Fangen K, et al. True user involvement by people living with HIV is possible: description of a user-driven HIV clinic in Norway. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2015;26(6):732–42.

Carlson A, Rosenqvist U. Locally developed plans for quality diabetes care: worker and consumer participation in the public healthcare system. Health Educ Res. 1990;5(1):41–52.

Hopkins C, Niemiec S. The development of an evaluation questionnaire for the Newcastle Crisis Assessment and Home Treatment Service: finding a way to include the voices of service users. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2006;13(1):40–7.

Tollyfield R. Facilitating an accelerated experience-based co-design project. Br J Nurs. 2014;23(3):136–41.

Xie A, Carayon P, Cartmill R, Li Y, Cox ED, Plotkin JA, et al. Multi-stakeholder collaboration in the redesign of family-centered rounds process. Appl Ergon. 2015;46 Pt A:115–23.

Swarbrick MP, Brice GH Jr. Sharing the message of hope, wellness, and recovery with consumers psychiatric hospitals. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. 2006;9:101–9.

Owens C, Farrand P, Darvill R, Emmens T, Hewis E, Aitken P. Involving service users in intervention design: a participatory approach to developing a text-messaging intervention to reduce repetition of self-harm. Health Expect. 2011;14(3):285–95.

Factor SH, Galea S, de Duenas Geli LG, Saynisch M, Blumenthal S, Canales E, et al. Development of a “survival” guide for substance users in Harlem, New York City. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29(3):312–25.

Ferreira-Pinto JB, Ramos R. HIV/AIDS prevention among female sexual partners of injection drug users in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. AIDS Care. 1995;7(4):477–88.

Pilgrim D, Waldron L. User involvement in mental health service development: how far can it go? J Ment Health. 1998;7(1):95–104.

Gibson F, Aslett H, Levitt G, Richardson A. Follow up after childhood cancer: a typology of young people’s health care need. Clin Eff Nurs. 2005;9:133–46.

Wistow G, Barnes M. User involvement in community care: origins, purposes and application. Public Adm. 1993;71:279–99.

Jones SP, Auton MF, Burton CR, Watkins CL. Engaging service users in the development of stroke services: an action research study. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(10):1270–9.

Lord J, Ochocka J, Czarny W, MacIlivery H. Analysis of change within a mental health organization: a participatory process. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 1994;21(4):327–39.

Brooks F. “When I was on the ward”: the contribution of patient narratives to public involvement in health care decision-making. Neurol Rehabil. 2008;14(1):24–30.

Acri M, Olin SS, Burton G, Herman RJ, Hoagwood KE. Innovations in the identification and referral of mothers at risk for depression: development of a peer-to-peer model. J Child Fam Stud. 2014;23(5):837–43.

van Staa A, Jedeloo S, Latour JM, Trappenburg MJ. Exciting but exhausting: experiences with participatory research with chronically ill adolescents. Health Expect. 2010;13(1):95–107.

Enriquez M, Cheng AL, Kelly PJ, Witt J, Coker AD, Kashubeck-West S. Development and feasibility of an HIV and IPV prevention intervention among low-income mothers receiving services in a Missouri Day Care Center. Violence Against Women. 2010;16(5):560–78.

Thomson A, Rivas C, Giovannoni G. Multiple sclerosis outpatient future groups: improving the quality of participant interaction and ideation tools within service improvement activities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:105.

Cawston PG, Mercer SW, Barbour RS. Involving deprived communities in improving the quality of primary care services: does participatory action research work? BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:88.

Ennis L, Robotham D, Denis M, Pandit N, Newton D, Rose D, et al. Collaborative development of an electronic personal health record for people with severe and enduring mental health problems. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:305.

Erwin K, Martin MA, Flippin T, Norell S, Shadlyn A, Yang J, et al. Engaging stakeholders to design a comparative effectiveness trial in children with uncontrolled asthma. J Comp Eff Res. 2016;5(1):17–30.

Coker TR, Moreno C, Shekelle PG, Schuster MA, Chung PJ. Well-child care clinical practice redesign for serving low-income children. Pediatrics. 2014;134(1):e229–39.

Godfrey M, Smith J, Green J, Cheater F, Inouye SK, Young JB. Developing and implementing an integrated delirium prevention system of care: a theory driven, participatory research study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:341.

Reeve C, Humphreys J, Wakerman J, Carroll V, Carter M, O’Brien T, et al. Community participation in health service reform: the development of an innovative remote aboriginal primary health-care service. Aust J Prim Health. 2015;21(4):409–16.

Barnes D, Carpenter J, Bailey D. Partnerships with service users in interprofessional education for community mental health: a case study. J Interprof Care. 2000;14(2):189–200.

Buck DS, Rochon D, Davidson H, McCurdy S. Involving homeless persons in the leadership of a health care organization. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(4):513–25.

Mendenhall T, Berge JM, Harper P, GreenCow B, LittleWalker N, WhiteEagle S, BrownOwl S. The Family Education Diabetes Series (FEDS): community-based participatory research with a midwestern American Indian community. Nurs Inq. 2010;17(4):359–72.

Fitzgerald MM, Kirk GD, Bristow CA. Description and evaluation of a serious game intervention to engage low secure service users with serious mental illness in the design and refurbishment of their environment. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(4):316–22.

Forbat L, Hubbard G, Kearney N. Patient and public involvement: models and muddles. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(18):2547–54.

Barnes M, Wistow G. Learning to hear voices: listening to users of mental health services. J Ment Health. 1994;3:525–40.

Government HMs. No health without mental health: a cross-government outcomes strategy. In: Health Do. London: Her Majesty's (HM) Government; 2011.

Munro K, Ross KM, Reid M. User involvement in mental health: time to face up to the challenges of meaningful involvement? Int J Ment Health Promot. 2006;8:37–44.

Hunter R, Cameron R, Norrie J. Using patient-reported outcomes in schizophrenia: the Scottish Schizophrenia Outcomes Study. J Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(2):240–5.

Coulter A. The Autonomous Patient: Ending Paternalism in Medical Care. London: Stationery Office (for the Nuffield Trust); 2002.

Groene O, Sunol R, Klazinga NS, Wang A, Dersarkissian M, Thompson CA, et al. Involvement of patients or their representatives in quality management functions in EU hospitals: implementation and impact on patient-centred care strategies. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(Suppl 1):81–91.

Abelson J, Li K, Wilson G, Shields K, Schneider C, Boesveld S. Supporting quality public and patient engagement in health system organizations: development and usability testing of the public and patient engagement evaluation tool. Health Expect. 2016;19(4):817–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12378.

Mockford C, Staniszewska S, Griffiths F, Herron-Marx S. The impact of patient and public involvement on UK NHS health care: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(1):28–38.

van C, McInerney P, Cooke R. Patients’ involvement in improvement initiatives: a qualitative systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(10):232–90.

Bee P, Price O, Baker J, Lovell K. Systematic synthesis of barriers and facilitators to service user-led care planning. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(2):104–14.

Liang L, Cako A, Urquhart R, Straus SE, Wodchis WP, Baker GR, et al. Patient engagement in hospital health service planning and improvement: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e018263.

De Vries R, Stanczyk A, Wall IF, Uhlmann R, Damschroder LJ, Kim SY. Assessing the quality of democratic deliberation: a case study of public deliberation on the ethics of surrogate consent for research. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(12):1896–903.

Blickem C, Kennedy A, Vassilev I, Morris R, Brooks H, Jariwala P, et al. Linking people with long-term health conditions to healthy community activities: development of Patient-Led Assessment for Network Support (PLANS). Health Expect. 2013;16(3):e48–59.

Bone LR, Edington K, Rosenberg J, Wenzel J, Garza MA, Klein C, et al. Building a navigation system to reduce cancer disparities among urban black older adults. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2013;7(2):209–18.

Hall SJ, Samuel LM, Murchie P. Toward shared care for people with cancer: developing the model with patients and GPs. Fam Pract. 2011;28(5):554–64.

Higgins A, Hevey D, Gibbons P, O’Connor C, Boyd F, McBennett P, et al. A participatory approach to the development of a co-produced and co-delivered information programme for users of services and family members: the EOLAS programme (paper 1). Ir J Psychol Med. 2016;34(01):19–27.

Jones EG, Goldsmith M, Effken J, Button K, Crago M. Creating and testing a deaf-friendly, stop-smoking web site intervention. Am Ann Deaf. 2010;155(1):96–102.

MacNeill V. Forming partnerships with parents from a community development perspective: lessons learnt from sure start. Health Soc Care Community. 2009;17(6):659–65.

Rose D. Partnership, co-ordination of care and the place of user involvement. J Ment Health. 2003;12(1):59–70.

Walsh M, Hostick T. Improving health care through community OR. J Oper Res Soc. 2005;56:193–201.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement for the funding for this study. Yvonne Bombard was funded by a Postdoctoral Fellowship and a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and CIHR Strategic Training Fellowships of “Public Health Policy” and “Health Care, Technology and Place” during the conduct of this research. Jean-Louis Denis holds a Canada Research Chair on governance and transformation of health systems and organizations. We thank Drs. Sharon Strauss, Andrea Tricco, and Monika Kastner for the advice on systematic review methodology.

None of these funding agencies played any role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Funding

The Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement provided funding for this study but were not involved in the conception or conduct of the systematic review.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset(s) supporting the conclusions of this article is(are) included within the article (and its additional file(s)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YB and GRB conceived of the study and participated in its design and coordination. KO and PB retrieved the records. EO, CF, and PB screened the records. EO and CF extracted the data from the eligible articles. YB and GRB developed the initial interpretations of the data and participated in the data analysis. SC conducted the quality appraisal. YB drafted the manuscript. YB and GRB revised the manuscript. J-LD and M-PP were involved in the study design and oversight; they reviewed the initial data analyses and suggested revisions to the versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests. All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S3. PRISMA checklist. (DOC 63 kb)

Additional file 2:

Figure S1. PRISMA diagram. (DOC 57 kb)

Additional file 3:

Table S1. Analysis of patient engagement strategies to improve quality of care. Identification of facilitators and barriers to patient engagement and subsequent evaluation of patient experiences. (DOCX 160 kb)

Additional file 4:

Table S2. Quality appraisal. Quality appraisal of review articles based on Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(9):1284–99. (DOCX 117 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bombard, Y., Baker, G.R., Orlando, E. et al. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implementation Sci 13, 98 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0784-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0784-z