Abstract

Background

Healthcare systems around the world have been responding to the demand for better integrated models of service delivery. However, there is a need for further clarity regarding the effects of these new models of integration, and exploration regarding whether models introduced in other care systems may achieve similar outcomes in a UK national health service context.

Methods

The study aimed to carry out a systematic review of the effects of integration or co-ordination between healthcare services, or between health and social care on service delivery outcomes including effectiveness, efficiency and quality of care. Electronic databases including MEDLINE; Embase; PsycINFO; CINAHL; Science and Social Science Citation Indices; and the Cochrane Library were searched for relevant literature published between 2006 to March 2017. Online sources were searched for UK grey literature, and citation searching, and manual reference list screening were also carried out. Quantitative primary studies and systematic reviews, reporting actual or perceived effects on service delivery following the introduction of models of integration or co-ordination, in healthcare or health and social care settings in developed countries were eligible for inclusion. Strength of evidence for each outcome reported was analysed and synthesised using a four point comparative rating system of stronger, weaker, inconsistent or limited evidence.

Results

One hundred sixty seven studies were eligible for inclusion. Analysis indicated evidence of perceived improved quality of care, evidence of increased patient satisfaction, and evidence of improved access to care. Evidence was rated as either inconsistent or limited regarding all other outcomes reported, including system-wide impacts on primary care, secondary care, and health care costs. There were limited differences between outcomes reported by UK and international studies, and overall the literature had a limited consideration of effects on service users.

Conclusions

Models of integrated care may enhance patient satisfaction, increase perceived quality of care, and enable access to services, although the evidence for other outcomes including service costs remains unclear. Indications of improved access may have important implications for services struggling to cope with increasing demand.

Trial registration

Prospero registration number: 42016037725.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It has been argued that growing financial and service pressures in the UK National Health Service (NHS) cannot be tackled without transforming how health and social care are delivered. The NHS Five Year Forward View Plan published in 2014 [1] sets out how services need to change, and emphasises the requirement for greater integration of care [2]. It is argued that increased service integration will enable the achievement of a financially sustainable health and social care system in the NHS by 2020. New models of integrated care are charged with achieving more care beyond the hospital walls, change in the size and shape of acute hospitals, and increased attention to prevention and population health [3]. The drive to introduce new models in the NHS has been formidable, with “vanguard” sites across England funded to test seven new care models that integrate services around the patient. Their impact is currently in the process of being evaluated.

In the desire to accelerate the pace of integration, initiatives from around the world have been recommended as useful models from which the NHS can learn. However, some authors have emphasised that it is imperative to consider contextual differences before implementing the same models in different services and location [4]. While it is important to learn from the international literature, positive outcomes reported in these international models may not be assumed in a UK setting, requiring careful scrutiny of potentially differing effects. There have been calls for greater clarity regarding precisely how integration may impact on outcomes [5]. Doubts regarding the ability of new models to deliver expected benefits have also recently been voiced, with a report from the National Audit Office concluding that progress towards integration has been slower and less successful than envisaged [6]. A systematic review published in 2017 examined initiatives to move care from hospitals to the community, and similarly concluded that anticipated cost savings could not be assumed [7].

In a landscape of changing service delivery and uncertainty regarding effectiveness of new models, we undertook a systematic review to examine the literature on outcomes of integrated care. Given the potential for learning from integrated models across the world, we aimed in particular to compare evidence from the UK and international literature, to explore where similarities and difference in effects have been reported. This paper focuses on data relating to the effects of models of integrated care on actual and perceived service delivery, including the efficiency, effectiveness and quality of care. Other findings from this study including factors influencing implementation and outcomes are reported elsewhere (Baxter et al. In Press).

Methods

Highly complex system-wide interventions such as models of integrated care provide considerable challenges for systematic review methods [8]. Systematic reviews have typically sought clear intervention-outcome effects from “gold standard” randomised experimental studies. However, recent years have witnessed substantial growth in the range of review methods available, with recognition that different review types are appropriate for answering differing questions and purposes [9, 10]. We selected an appropriate review method to fulfil the three requirements of: examination of multiple types of integrated care initiatives and service delivery outcomes; inclusion of studies of varying designs across the hierarchy of evidence; and learning most applicable to the UK NHS context. We therefore adopted an approach drawing on work by Pawson, [11] which stresses that both rigour and relevance are important when scrutinising complex outcome patterns. We included studies of both comparator and non-comparator design from the UK (as these data were considered to privilege relevance), whereas we prioritised international systematic reviews and international primary studies with comparative design (thereby privileging rigour).

Literature search strategy

The study protocol was registered with the PROSPERO database (number 42016037725) and was made available on the National Institute for Health Research website (available as an Additional file 1: Appendix S1) The review was conducted in line with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Additional file 1: Appendix S2) [12].

The information specialist on the team carried out systematic searches of health, medical and social care databases in September 2016. We searched electronic databases including MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, PscyINFO, SCI and SSCI, and CINAHL. Further details of the search strategy are available in the Additional file 1: Appendix S3. Other iterative searching techniques were also employed, including hand searching of reference lists of primary studies and other reviews. We searched for grey literature via reference lists and also via UK websites including that of the Kings Fund (https://www.kingsfund.org.uk) and NHS England (https://www.england.nhs.uk). In May 2017 we conducted a citation search to identify any literature published subsequent to the formal bibliographic searches.

Eligibility criteria

We defined “models of integrated care” as changes to health or both health and health-related service delivery which aim to increase integration and/or coordination.

-

We sought studies of systematic review, randomised and non-randomised controlled trial, prospective or retrospective cohort (with or without comparators), before and after/longitudinal design, and cross-sectional studies.

-

We included studies reporting any outcome relating to the delivery of services (effectiveness or efficiency or quality) and/or the effect on patients and staff delivering services.

-

Studies were required to have been carried out in a developed country (a member of the Organisation for Economic Collaboration and Development) and to have been published since 2006 in English, or have an English abstract. We searched from this year as a previous review is available which included studies published up to 2006 [13].

Studies were excluded if they reported only clinical, rather than service delivery outcomes, or if integrated services did not include healthcare. We included grey literature from the UK in the form of reports, but conference abstracts and theses were excluded.

Data collection

Retrieved citations were uploaded to an EndNote database, and title and abstracts (where available) of papers were screened by three reviewers against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Any queries regarding inclusion were discussed by the full team at regular (fortnightly) team meetings. After independent screening and discussion of the first 5% of the database to establish agreement, further screening was carried out by a single reviewer, with checking of a 10% sample by other team members.

Articles which met the inclusion criteria were read in full and data extracted by the team of three reviewers. Data extractions were second-checked by a different member of the team. Papers excluded and the reason for exclusion was recorded (available as Additional file 1: Appendix S4). The extraction form collected data on: first author/year; study design; sample size; population characteristics (type of group, condition/department, sex, age, other details reported); context; data collection method; outcome measures; type and details of the intervention; summary of results; main author conclusions; reported associations; and potential factors relating to applicability. The extraction form for systematic review included number of studies in the review, together with details of the inclusion criteria. Double counting was avoided by noting where included primary studies were also contained in included systematic reviews.

Assessment of risk of bias

Quality assessment was based on the hierarchy of study design, together with use of a variety of checklists for each study type. For studies using comparative design we considered sources of potential bias based on the Cochrane criteria (selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias, detection bias, reporting bias) [14]. Where studies utilised before and after (pre-post) designs with no comparator group, or reported systematic reviews, we used the National Institutes of Health checklists [15]. In line with Cochrane recommendation we did not score elements, and instead provided a narrative rather than numerical indication of quality [14]. The completed checklists are available as Additional file 1.

Data synthesis and analysis

Our protocol allowed for meta-analysis if heterogeneity permitted. However, the wide variety of models of integrated care, and multiple and complex elements contained therein, together with the heterogeneity of outcomes measured, contra-indicated the use of summary statistics. Instead, we report where there is greater or lesser strength (or certainty) in the evidence for each outcome reported [16].

It is important that any assessment of strength of evidence considers not only quality and volume of studies, but also considers consistency [17]. Our evaluation therefore draws on work by Hoogendoom [17], together with principles from the GRADE and CERQUAL rating schemes [16, 18], and our work from a previous systematic review with diverse evidence [19] to indicate a rating of strength (certainty) for each reported outcome across the included studies. Due to the nature of the intervention no studies were able to achieve the “gold standard” of double blinding and full randomisation and thus provide evidence considered to be “strong”. We therefore used comparator labels (stronger versus weaker), to provide a relative evaluation of strength. Appraisal of strength of evidence was undertaken by the research team at a series of meetings to establish consensus.

Each outcome reported in a study was recorded as either “increase”, “reduction” or “no significant difference (statistical significance).” We used these terms, as for some outcomes the judgement of being positive or negative depends on ones point of view. For example an increase in service usage may be positive for patients or the service, but may also be negative in terms of costs or detrimental effect on other services. Following rating of the outcomes in each individual study, we then applied an overall rating to the evidence across all studies which reported the same outcome. The rating scale was as follows: “stronger evidence” represented generally consistent findings in multiple studies with a comparator group design, or three or more systematic reviews; “weaker evidence” represented generally consistent findings in one study with a comparator group design and several non-comparator studies, or two systematic reviews, or multiple non-comparator studies; “very limited evidence” represented an outcome reported by a single study; and finally, “inconsistent evidence” represented an outcome where fewer than 75% of studies agreed on the direction of effect.

We separately rated evidence from the UK studies, evidence from systematic reviews, evidence from the international comparator studies, and evidence from international non-comparator studies, and then provided an overall rating of effect across the study types.

Results

Literature search results and study selection

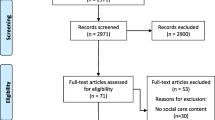

Following screening of 13,323 unique citations, 167 documents representing 153 unique studies were eligible for inclusion. See Fig. 1 for a diagram illustrating the study selection process.

The list of studies excluded at the full paper selection stage and reasons for their exclusion is available as an Additional file 1: Appendix S4).

Characteristics and quality of included studies

Of the 167 included documents, 54 reported studies carried out in the UK [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73], and 43 reported systematic reviews [13, 74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115], we included 49 high quality studies from outside the UK using comparator group designs [116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164]. We included 21 low quality non-UK studies (no comparator group) [165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185] within a “light touch” analysis.

We observed little overlap between primary studies and reviews, with time lags in publication of the systematic reviews meaning that the majority of their primary studies preceded our inclusion date of 2006. Figure 2 summarises the country of origin for the different types of study design.

While there were large numbers of studies from both primary/community services, and acute care, the larger group was initiatives implemented outside hospital settings. Thirty five studies were carried out in primary care/community contexts, 24 studies were carried out solely in hospital settings, and two were carried out in nursing homes. Nineteen studies specifically described both health and social care services being included in the integration, although reporting of specific details of partner organisations/services was often limited. Authors did not make links between the context and outcomes of initiatives, apart from reported issues regarding staff training and retention in social care [38]. and the benefit of physical co-location of services [32].

Of the included 54 UK articles, 16 reported findings from studies using higher quality comparator designs [25, 28, 30, 31, 34, 38, 40, 44, 49, 60, 63, 64, 67, 68, 71, 72]. Only two had utilised some form of random allocation to condition [44, 49], with allocation concealment not possible due to the nature of the intervention. Blinding of participants and personnel was also limited or not possible, with only four studies achieving this [30, 31, 49, 72]. Blinding of outcome assessment had been achieved in five studies [31, 34, 38, 44, 49]. The included UK studies fared better in regard to completion of outcome assessment, and reporting was assessed as being accurate for all but one [44] which had insufficiently discussed the study limitations. Overall therefore the UK studies were all considered to be at risk of potential bias, with none achieving all six criteria for reducing potential sources of bias.

The international comparative design studies rated slightly better in terms of randomisation with 19 (reported in 26 papers) having random allocation [116,117,118,119, 123,124,125,126,127,128, 131, 132, 136, 137, 139, 142, 144, 147,148,149, 152, 155, 156, 161, 163, 164], although only nine studies (reported in 14 papers) achieved allocation concealment [116, 118, 119, 123,124,125, 127, 128, 131, 132, 139, 161, 163, 164]. As with the UK studies, blinding was problematic as patients were unable to be blinded to their study arm. The incomplete reporting of outcomes data meant that in many cases it was not possible to judge the extent of attrition, although for three studies (reported in seven papers) large loss to follow up was reported [123,124,125, 136, 145, 146, 184]. Reporting was poor in around a third of the studies, making it difficult to judge the extent of possible selective reporting. Other limitations included small sample sizes leading to inadequate statistical power, with some concerns regarding the processes of allocation. As with the UK comparative design studies, none met all the criteria for reduction of potential bias.

The UK before and after/longitudinal studies demonstrated similar issues regarding blinding, with only one study clearly reporting that outcome assessors were blinded [66]. Generally participants recruited appeared to be representative of the population of interest, although often it was difficult to ascertain the recruitment process. Just over half the included studies reported sample sizes that were sufficiently large to have confidence in the findings. Only a third were judged to have clearly described the intervention and its delivery, and none reported taking measures at multiple time points prior to the intervention. Only just over half used statistical measures (such as p values) to evaluate change over time.

Elements of models of integrated care

The majority of the included models of integrated care were complex and multi-element interventions. The elements contained within them could be divided into four main categories: first, those with a focus on improving patient care directly; secondly, those that focused on making changes to organisations and systems; thirdly, those that focused on changing staff employment or working practices; and finally, those that addressed financial or governance aspects of integration. Many models incorporated multiple elements, and it was often challenging to elucidate the form and components due to limited reporting. The greatest number of elements we could identify in a single intervention was nine, which compared with other integrated care initiatives containing a single element. Typically models contained four to six elements. Case manager/case co-ordinator initiatives were more common in the international literature, whereas integrated care pathways/plans were more often a feature of models in the UK. Figure 3 summarises elements of new models of integrated care in the included studies.

Effect on each outcome

We identified an extensive range of outcomes from the literature. We grouped these into three main areas: those relating to usage of health care resources; those relating to the quality of care received by patients; and outcomes for staff working experience. We adopted the four-item rating scale described in the Methods section to evaluate the quantity and consistency of available evidence for each outcome. We provide the rating for studies from the UK, international systematic reviews, international primary studies and finally an overall rating of available evidence. Where reports of outcomes were duplicated in multiple papers from the same study we identify only one instance, to avoid over-representation of these data. Additional file 2: Table S1 details the number of studies reporting each outcome, with each study (or papers from the same study) represented by either a plus “+” meaning that the study reported an increase for this outcome, or a plus/minus sign “±” meaning that the study reported no significant change for this outcome, or a minus sign “-” meaning that the study reported a reduction for this outcome. Symbols highlighted in grey are from UK studies using a higher quality comparative design.

The evidence was rated as stronger for three outcomes: that integrated care leads to an increase in patient satisfaction; that integrated care leads to increased perceived quality of care (staff perception in the UK studies, staff and patient perceptions in the non-UK studies); and that integrated care can lead to increased/improved patient access. UK studies indicated evidence of a reduction in waiting times and out-patient appointments, although the international literature as a whole was more inconclusive.

Nine of 11 UK studies evaluating differing types of interventions across a range of conditions and services reported increased levels of patient satisfaction [21, 23, 29, 32, 37, 44, 52, 61, 69]. All 11 systematic reviews reporting this outcome concluded that the evidence suggested a positive effect on patient satisfaction [13, 82, 85, 86, 92, 99, 102, 110, 111, 114, 184]. Four of six international comparator studies similarly reported increased satisfaction amongst older, acute and paediatric patient populations following service integration, case management and patient-centred medical home interventions [119, 136, 150, 159].

Four UK intervention studies reported staff perceptions of increased quality of care following service redesign, case management or integrated pathway interventions in hospital or primary care for older adults, general caseloads or patients with C-difficile infection [31, 50, 58, 69]. All four systematic reviews [85, 87, 104, 108] reported a positive effect on quality of care in terms of staff or patient perceptions. One of two international comparator studies (reported in three papers) supported the finding that quality of care was perceived by patients to have improved [123,124,125].

Five included (non-comparator) UK intervention studies reported that access to services in the community and/or specialists/intermediate care had increased [35, 41, 59, 72, 73]. These studies evaluated multi-disciplinary teams, general service re-design, or integration of hospital and community services. Two systematic reviews reported that access to services had “improved” [76, 104]. Three international comparator studies (reported in five papers) supported the finding that integrated care initiatives improved access [117, 123,124,125,126]. Two international non-comparator studies similarly reported improved access to services for patients [167, 179].

In regard to similarities and differences between studies carried out in the UK and in other countries, we found three areas of variance in rating between UK evidence and the evidence overall. Five UK studies offered evidence of a reduction in waiting times [27, 41, 49, 61, 71]. The international evidence however, is more inconclusive, with three studies indicating a reduction, two studies indicating no effect, and one an increase. UK studies found a reduction in out-patient appointments [31, 44, 53, 60, 67], however, the two international studies reporting this outcome found no significant effect. We found weaker UK-only evidence in three studies for the likelihood of care meeting patient preferences (predominantly end of life decisions) [20, 39, 65] with no included international studies evaluating this outcome.

Evidence regarding the following outcomes was rated as inconsistent: number of clinician contacts (five indicated a reduction, and three an increase); number of GP appointments (two UK studies reported a reduction and another UK study no difference); length of stay (24 studies reported a reduction, two studies found an increase, and 11 no effect); unscheduled admissions (10 studies found a reduction, two an increase; and nine no effect); number of admissions (24 studies found a reduction, five reported an increase, and nine no effect) although considered alone the systematic reviews provided stronger evidence of a reduction; re-admissions (nine studies, with eight from the same authors reported no effect, two studies found an increase and two a reduction); attendance at accident and emergency (nine studies found a reduction, two an increase and eight no effect); quality of care standards (two studies reported an increase and one no difference); and staff work experience (two reviews of UK studies indicated improved experience, and one international study indicated no difference).

The rating of very limited evidence (insufficient studies) was assigned to the following outcomes: prescribing rates; access to resources; time spent in accident and emergency department; the number of incidents/complaints; and identification of unmet need.

We also examined evidence relating to wider impacts across the whole of a healthcare system. The evidence was inconsistent regarding the impact on cost of provision (17 studies reported a reduction, two an increase and 20 no difference); community care activity (four studies reported a reduction, five an increase, and one no difference); secondary care activity (no studies reported an increase, four found a reduction, and two no difference); and overall healthcare utilisation (two systematic reviews found the evidence was unclear).

We explored the potential for sub-group differences between different types of patients. Figure 4 summaries the types of patients and conditions in the studies included in the review.

We examined the data regarding outcomes and impacts for studies in the two largest sub-groups of patients - older adults, and populations described as having complex needs. We then compared this to the strength of evidence ratings assigned to the included studies as a whole. The effect of integrated care initiatives in older adult populations echoed the strength rating for all studies, with reports of increased access and patient satisfaction, and inconsistency in regard to admissions, emergency admissions, length of stay, patient contacts/service usage, and costs.

In contrast to the wider evidence base however, the evidence on patients described as having “complex needs”, suggested a stronger indication of positive outcomes in terms of reduced admissions and emergency department use, and weaker strength of evidence regarding reduced length of stay. The studies all utilised non-comparator designs however, so this indication needs to be treated with caution. We also looked for any patterns in regard to the type of initiatives that appeared to lead to more positive outcomes, with little clarity in signal beyond suggesting that integrated pathways as “stand alone” interventions may have a limited effect.

Discussion

Models of integrated care encompass diverse initiatives that aim to improve integration of care across healthcare and between health and social care services. We identified diverse and frequently contradictory outcomes for models of integrated care reported in the included literature. Three outcomes appeared to offer stronger evidence of effect: firstly, that integrated care leads to increased patient satisfaction; secondly, that integration increases perceived quality of care; and thirdly, that integrated care increases patient access to services. UK-only evidence indicated that patient waiting time and outpatient appointments may be reduced, and patient wishes at end of life are met more often (although inconsistency or lack of evidence for these effects was found in the international literature). The system-wide impact on community and hospital-based services was unclear, with reports of both increased and decreased use of community services, although we identified no evidence to suggest that models of integrated care increase use of secondary care. Neither was there clear evidence regarding whether models of integrated care are cost neutral, increase or reduce costs. The review identified numerous changes to delivery of services which are subsumed within the label of models of integrated care. As highly complex interventions, these models challenge linkage of particular elements of initiatives to effects, with a lack of clarity on which key elements are causally associated with positive outcomes.

We highlight the challenges inherent when defining models of integrated care, given the lack of agreed definition and clear boundaries to the term. This limitation may have resulted relevant work being excluded from this review. We found it particularly challenging to distinguish between new models of care that are integrated/co-ordinated from those that are not during the screening and selection process. “Integration” could be used in a variety of ways, including to describe interventions which related to enhanced care or quality assurance but did not include staff working in new ways. Although our search terms enabled relevant citations to be retrieved, we recognise that indexing may be imperfect, and we may have not identified all studies of relevance. We also acknowledge a potential issue of publication bias, with studies reporting less positive outcomes potentially under-represented in the review. We highlight the paucity of literature reporting objective quality of care outcomes, with our findings regarding the effect on quality based on staff or patient perceptions.

One particular limitation relates to the lack of statistical summary of effectiveness (meta-analysis) although we would argue that not only did the heterogeneity of interventions and outcomes preclude this type of analysis, but also, in exploring the complexity of the area a strength of evidence approach was beneficial. Included studies highlighted the challenges in identifying causal relationships between models of integrated care, and service delivery impacts [76, 87, 120,121,122]. In view of this challenge, we used strength of evidence ratings to summarise where greater or lesser certainty existed in the literature, considering quality, volume and consistency of the evidence identified. Reporting strength by volume of studies (“vote counting”) may be imperfect, primarily indicating where there has been research activity. In exploring consistency as well as volume when assessing strength of evidence, we have sought to some extent to mitigate this limitation.

Evaluating outcomes and impacts from models of integrated care presents challenges in determining what a “good” outcome may be. In terms of financial outcomes, the effects of integrated care may be perceived differently by different stakeholders, offering contradictory incentives for achieving change. At an organisational level for example reduced activity in one sector may mean financial losses. There are also known to be considerable challenges in transferring money or resources between organisations in response to changed levels of activity. Another tension exists between cost-saving and provision of improved quality of care. Some studies reported that increasing quality of care for patients may come at increased cost for services already facing financial pressure.

The potentially positive outcome of increasing ease of access for patients, also offers contradictory effects. Improved access may be perceived positively by patients, and enable serious conditions to be identified and treated earlier; but also may incur a detrimental effect on costs and capacity. Recognition is growing that rather than new models of integration within services, reform at scale is required, with reconfiguration at a whole systems level including in the UK new forms of commissioning and contracting (the way that NHS organisations assess the needs of an area and then draw up contracts with suitable providers) [3]. The literature included in this review rarely focused on organisational change within integrated care models. This may reflect the challenges inherent in the organisational change process [186]. Some authors highlighted the continuance of varied pre-existing governance arrangements following integration of organisations, with progress on new models often reported to be particularly limited in the areas of budgets, financial, and contracting mechanisms [187].

The implementation of highly complex whole-system change interventions such as new forms of integration is known to be challenging [188], and differing degrees of success in implementation may contribute to the varying outcomes reported. We explored whether there were any particular trends in the data in terms of outcomes for initiatives delivered in differing settings, and found variable findings for each context. Similarly, examination of integration amongst health services versus combined health and social care did not indicate any particular trends in effectiveness. While there appeared to be no clear pattern of differential outcomes between settings or initiatives, there appeared to be potential for more positive outcomes amongst those categorised by authors as having “complex needs”, although currently most research evidence comes from studies in older adults. Further research is required to explore the potential for models of integrated care to impact on the care for other patient groups with complex needs.

Conclusions

This review adds to the growing evidence that integrated care initiatives rarely lead to unequivocally positive effects, although the calls for integrated care have never been stronger. The potential for integrated services to increase patient contacts, is a particular concern in already over-stretched services. New models of care may be best targeted to particular patient groups (such as those with complex needs) rather than being seen as a panacea for all.

We identified surprisingly little evidence regarding the impact of integrated care models on patient experiences of services, beyond measures of reported patient satisfaction. There seems a need for further attention to how reconfiguration impacts on patients and carers, including whether service users perceive any change, or have greater knowledge of or involvement in services.

References

England NHS. Five year forward view. London: National Health Service England; 2014. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf.

Shortell SM, Addicott R, Walsh N, Ham C. The NHS five year forward view: lessons from the United States in developing new care models. BMJ. 2015;350:h2005. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h2005.

Ham C, Murray R. Implementing the NHS five year forward view: aligning policies with the plan. London: Kings Fund; 2015. Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/implementing-the-nhs-five-year-forward-view-kingsfund-feb15.pdf.

Ahmed F, Mays N, Ahmed N, Bisognano M, Gottlieb G. Can the accountable care organization model facilitate integrated care in England? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2015;20:261–4.

Robertson H. Integration of health and social care: a review of literature and models implications for Scotland. Royal College of Nursing: Edinburgh; 2011.

National Audit Office. Health and social care integration. London: National Audit Office; 2017. Available at: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Health-and-social-care-integration.pdf.

Imison C, Curry N, Holder H, Castle-Clarke S, Nimmons D, Appleby J, et al. Shifting the balance of care: great expectations. London: Nuffield Trust; 2017. Available at: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-02/shifting-the-balance-of-care-report-web-final.pdf.

Petticrew M, Rehfuess E, Noyes J, Higgins J, Mayhew A, Pantoja T, et al. Synthesizing evidence on complex interventions: how meta-analytical, qualitative, and mixed-method approaches can contribute. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:1230–43.

Munn Z, Stern C, Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Jordan Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:5.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26:91–108.

Pawson R. Evidence-based policy: a realist perspective. London: Sage; 2006.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche P, Ioannidis J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700.

Powell Davies G, Williams AM, Larsen K, Perkins D, Roland M, Harris MF. Coordinating primary health care: an analysis of the outcomes of a systematic review. Med J Aust. 2008;188:S65–8.

Gardner K, Banfield M, McRae I, Gillespie J, Yen L. Improving coordination through information continuity: a framework for translational research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0590-5.

National Health Institute. Quality assessment of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Bathesda: National Heart Lung and Blood Institute; 2014.

Glenton C, Colvin CJ, Carlsen B, Swartz A, Lewin S, Noyes J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of lay health worker programmes to improve access to maternal and child health: qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010414.pub2.

Hoogendoom WE, Van Poppel MN, Bongers PM, Koes BW, Lex M. Physical load during work and leisure time as risk factors for back pain. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1999;25:387–43.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Woodcock J, Brozek J, Helfand M, et al. GRADE guidelines: 8. Rating the quality of evidence--indirectness. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:1303–10.

Baxter SK, Blank L, Woods HB, Payne N, Rimmer M, Goyder E. Using logic model methods in systematic review synthesis: describing complex pathways in referral management interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:1–9.

Addicott R, Dewar S. Improving choice at the end of life: a descriptive analysis of the impact and costs of the Marie curie delivering choice programme in Lincolnshire. London: Kings Fund; 2008.

Ahmad F, Roy A, Brady S, Belgeonne S, Dunn L, Pitts J. Care pathway initiative for people with intellectual disabilities: impact evaluation. J Nurs Manage. 2007;15:700–2.

Bakerly ND, Davies C, Dyer M, Dhillon P. Cost analysis of an integrated care model in the management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chronic Respir Dis. 2009;6:201–8.

Beacon A. Practice-integrated care teams -- learning for a better future. J Integrated Care. 2015;23:74–87.

Boyle A, Fuld J, Ahmed V, Bennett T, Robinson S. Does integrated emergency care reduce mortality and non-elective admissions? A retrospective analysis. Emerg Med J. 2012;29:208–12.

Boyle AA, Ahmed V, Palmer CR, Bennett TJ, Robinson SM. Reductions in hospital admissions and mortality rates observed after integrating emergency care: a natural experiment. BMJ Open. 2012;2 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000930.

Boyle AA, Robinson SM, Whitwell D, Myers S, Bennett TJ, Hall N, et al. Integrated hospital emergency care improves efficiency. Emergency Med J. 2008;25:78–82.

Choo T, Deb S, Wilkins J, Atiomo W. Evaluating the impact of the reconfiguration of gynaecology services at a university hospital NHS trust in the United Kingdom. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:428. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-428.

Clarkson P, Brand C, Hughes J, Challis D. Integrating assessments of older people: examining evidence and impact from a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2011;40(3):388–91.

Coupe M. Integrated care in Herefordshire: a case study. J Integrat Care. 2013;21:198–207.

Cunningham S, Logan C, Lockerbie L, Dunn MG, Prescott RJ. Effect of an integrated care pathway on acute asthma/wheeze in children attending hospital: cluster randomized trial. J Pediatrics. 2008;152:315–20.

Department of Health. National Evaluation of the Department of Health’s integrated care pilots. London: Department of Health; 2012. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215103/dh_133127.pdf.

Dodd J, Taylor CE, Bunyan P, White PM, Thomas SM, Upton D. A service model for delivering care closer to home. Prim Health Care Res Develop. 2011;12:95–111.

Graffy J, Grande M, Campbell J. Case management for elderly patients at risk of hospital admission: a team approach. Prim Health Care Res Develop. 2008;9:7–13.

Gravelle Hugh DM, Rod S, Penny S, Ruth B, Pickard S. Impact of case management (Evercare) on frail elderly patients: controlled before and after analysis of quantitative outcome data. Brit Med J. 2007;334:31.

Ham C. Working Together for Health: Achievements and Challenges in the Kaiser NHS Beacon Sites Programme. HSMC policy paper 6: Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham, 2010. Available at: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-social-sciences/social-policy/HSMC/publications/PolicyPapers/Policy-paper-6.pdf..

Harris M, Greaves F, Gunn L, Patterson S, Greenfield G, Car J, et al. Multidisciplinary group performance-measuring integration intensity in the context of the north West London integrated care pilot. Int J Integrat Care. 2013;13:e001. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.996.

Hawthorne G, Grzebalski DK. Service redesign: the experience of Newcastle diabetes service 2001-2007. Practical Diabetes Int. 2009;26:19–22.

Higginson IJ, Bausewein C, Reilly CC, Gao W, Gysels M, Dzingina A, et al. An integrated palliative and respiratory care service for patients with advanced disease and refractory breathlessness: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(12):979–87.

Hockley J, Watson J, Oxenham D, Murray SA. The integrated implementation of two end-of-life care tools in nursing care homes in the UK: an in-depth evaluation. Palliat Med. 2010;24(8):828–38.

Huws DW, Cashmore D, Newcombe RG, Roberts C, Vincent J, Elwyn G. Impact of case management by advanced practice nurses in primary care on unplanned hospital admissions: a controlled intervention study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8 https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-115.

Jha S, Moran P, Blackwell A, Greenham H. Integrated care pathways: the way forward for continence services? Eur J Obs Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;134:120–5.

Johnstone R, Jones A, Fowell A. Welsh collaborative care pathway project; 10 years experience of implementing and maintaining a care pathway for the last days of life. Int J Care Path. 2011;15(2):39–43.

Johnstone RP, Jones AR, Burton C, Fowell A. Evaluation of the welsh integrated care pathway (ICP) for the last days of life. Palliat Med. 2012;26:476.

Julian S, Naftalin NJ, Clark M, Szczepura A, Rashid A, Baker R. An integrated care pathway for menorrhagia across the primary-secondary interface: patients’ experience, clinical outcomes, and service utilisation. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(2):110–5.

Kent P, Chalmers Y. A decade on: has the use of integrated care pathways made a difference in Lanarkshire? J Nurs Manag. 2006;14:508–20.

Lamb BW, Jalil RT, Sevdalis N, Vincent C, Green JS. Strategies to improve the efficiency and utility of multidisciplinary team meetings in urology cancer care: a survey study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:377.

Letton C, Cheung C, Nordin A. Does an enhanced recovery integrated care pathway (ICP) encourage adherence to prescribing guidelines, accelerate postoperative recovery and reduce the length of stay for gynaecological oncology patients? J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33:296–7.

Levelt E, Thwaites B, Yadegarfar G. Integrated care pathway for acute coronary syndromes: does it help? J Integrat Care Path. 2008;12:5–9.

Lyon D, Miller J, Pine K. The Castlefields integrated care model: the evidence summarised. J Integrat Care. 2006;14:7–12.

MacLean A, Fuller RM, Jaffrey EG, Hay AJ, Ho-Yen DO. Integrated care pathway for Clostridium difficile helps patient management. Brit J Infect Control. 2008;9:15–7.

Mertes SC, Raut S, Khanduja V. Integrated care pathways in lower-limb arthroplasty: are they effective in reducing length of hospital stay? Int Orthop. 2013;37:1157–63.

Ng SM, Mariguddi S, Coward S, Middleton H. Paediatric community home nursing: a model of acute care. British J Nurs. 2014;23:209–12.

Offredy M, Cleary M, Bland A, Donovan A, Kelshiker A. Improving health and care for patients by redesigning services: the development and implementation of a clinical assessment service in harrow primary care trust. Qual Prim Care. 2008;16:95–102.

Paize F, White E, Heaf LJ, Baillie C, Kenny S, Couriel JM, et al. An integrated care pathway for optimizing the investigation and management of pediatric pleural empyema. J Pediatr Infect Dis. 2007;2:77–82.

Pearson V, Chant S. Different models of health and social care in Devon -- observations and implications for commissioners and providers. J Integrat Care. 2011;19:22–6.

Pettie JM, Dow MA, Sandilands EA, Thanacoody HK, Bateman DN. An integrated care pathway improves the management of paracetamol poisoning. Emerg Med J. 2011;29:482–6.

Richings C, Cook R, Roy A. Service evaluation of an integrated assessment and treatment service for people with intellectual disability with behavioural and mental health problems. J Intel Disabil. 2011;15:7–19.

Roberts JA, Maslin TK, Bakerly ND. Development of an integrated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease service model in an inner-city region in the UK: initial findings and 12-month results. Prim Care Respir J. 2010;19:390–7.

Roberts S, Unadkat N, Chandok R, Sawtell T. Learning from the integrated care pilot in West London. London J Prim Care. 2012;5:59–62.

Roland M, Lewis R, Steventon A, Abel G, Adams J, Bardsley M, et al. Case management for at-risk elderly patients in the English integrated care pilots: observational study of staff and patient experience and secondary care utilisation. Int J Integr Care. 2012;12 https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.850.

Rowlandson PH, Smith C. An interagency service delivery model for autistic spectrum disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Child: Care, Health Devel. 2009;35:681–90.

Ryan T, Hatfield B, Sharma I. Outcomes of referrals over a six-month period to a mental health gateway team. J Psychiat Mental Health Nurs. 2007;14:527–34.

Simmons D, Yu D, Wenzel H. Changes in hospital admissions and inpatient tariff associated with a diabetes integrated care initiative: preliminary findings. J Diabetes. 2014;6:81–9.

Sinclair L, Hunter R, Hagen S, Nelson D, Hunt J. How effective are mental health nurses in A&E departments? Emerg Med J. 2006:23:687–92.

Smith C, Hough L, Cheung C-C, et al. Coordinate my care: a clinical service that coordinates care, giving patients choice and improving quality of life. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2012;2:301–7.

Soljak M, Cecil E, Gunn L, Broddle A, Hamilton S, Tahir A, et al. Quality of care and health outcomes. North West London integrated care pilot evaluation: report on work Programme 3. London: Imperial College; 2013.

Steventon ABM, Billings J, Georghiou T, Lewis G. An evaluation of the impact of community-based interventions on hospital use. A case study of eight Partnership for Older People Projects (POPP). London: Nuffield Trust; 2011.

Stokes J, Kristensen SR, Checkland K, Bower P. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary team case management: difference-in-differences analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010468. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010468.

Tucker H, Burgis M. Patients set the agenda on integrating community services in Norfolk. J Integr Care. 2012;20:232–40.

Tucker S, Baldwin R, Hughes J, Benbow SM, Barker A, Burns A, et al. Integrating mental health services for older people in England - from rhetoric to reality. J Interprof Care. 2009;23:341–54.

Waller SL, Delaney S, Strachan MWJ. Does an integrated care pathway enhance the management of diabetic ketoacidosis? Diabetic Med. 2007;24:359–63.

Wilberforce M, Tucker S, Brand C, Abendstern M, Jasper R, Challis D. Is integrated care associated with service costs and admission rates to institutional settings? An observational study of community mental health teams for older people in England. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 2016;2:1208–16.

Windle K, Wagland R, Forder J, D’Amico F, Janssen D, Wistow G. National Evaluation of partnerships for older people projects, final report. London: Personal Services Research Unit; 2009. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3161-3.

Alexander JA, Bae D. Does the patient-centred medical home work? A critical synthesis of research on patient-centred medical homes and patient-related outcomes. Health Serv Manag Res. 2012;25:51–9.

Allen D, Gillen E, Rixson L. Systematic review of the effectiveness of integrated care pathways: what works, for whom, in which circumstances? Int J Evidence-Based Healthcare. 2009;7:61–74.

Allen D, Rixson L. How has the impact of ‘care pathway technologies’ on service integration in stroke care been measured and what is the strength of the evidence to support their effectiveness in this respect? Int J Evidence-Based Healthcare. 2008;6:78–110.

Beland F, Hollander MJ. Integrated models of care delivery for the frail elderly: international perspectives. Gac Sanit. 2011;25(Suppl 2):138–46.

Belanger E, Rodriguez C. More than the sum of its parts? A qualitative research synthesis on multi-disciplinary primary care teams. J Interprof Care. 2008;22:587–97.

Best A, Greenhalgh T, Lewis S, Saul JE, Carroll S, Bitz J. Large-system transformation in health care: a realist review. Milbank Q. 2012;90:421–56.

Boult C, Green AF, Boult LB, Pacala JT, Snyder C, Leff B. Successful models of comprehensive care for older adults with chronic conditions: evidence for the institute of medicine’s ‘retooling for an aging America’ report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(12):2328–37.

Butler M, Kane RL, McAlpine D, Kathol RG, Fu SS, Hagedorn H, et al. Integration of mental health/substance abuse and primary care. Evid Rep Technol Assess. 2008;173:1–362.

Cameron A, Bostock L, Lart R. Service user and carers perspectives of joint and integrated working between health and social care. J Integr Care. 2014;22:62–70.

Cameron A, Lart R, Bostock L, Coomber C. Factors that promote and hinder joint and integrated working between health and social care services: a review of research literature. Health Soc Care Comm. 2014;22:225–33.

Davies SL, Goodman C, Bunn F, Victor C, Dickinson A, Iliffe S, et al. A systematic review of integrated working between care homes and health care services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11 https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-320.

de Bruin SR, Versnel N, Lemmens LC, Molema CC, Schellevis FG, Nijpels G, et al. Comprehensive care programs for patients with multiple chronic conditions: a systematic literature review. Health Policy. 2012;107:108–45.

Eklund K, Wilhelmson K. Outcomes of coordinated and integrated interventions targeting frail elderly people: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Health Soc Care Comm. 2009;17:447–58.

Footman K, Garthwaite K, Bambra C, McKee M. Quality check: does it matter for quality how you organize and pay for health care? A review of the international evidence. Int J Health Serv : planning, administration, evaluation. 2014;44:479–505.

Genet N, Boerma WG, Kringos DS, Bouman A, Francke AL, Fagerstrom C, et al. Home care in Europe: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):207.

Homer CJ, Klatka K, Romm D, Kuhlthau K, Bloom S, Newacheck P, et al. A review of the evidence for the medical home for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e922–e37.

Huntley AL, Thomas R, Mann M, Huws D, Elwyn G, Paranjothy S, et al. Is case management effective in reducing the risk of unplanned hospital admissions for older people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Pract. 2013;30:266–75.

Hussain M, Seitz D. Integrated models of Care for Medical Inpatients with Psychiatric Disorders: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2014;55:315–25.

Jackson G, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, Bettjer JP, Kemper AR, Hasselblad V, et al. The patient-Centred medical home: a systematic review. Annals Intern Med. 2013;158:169–78.

Johansson G, Eklund K, Gosman-Hedstrom G. Multidisciplinary team, working with elderly persons living in the community: a systematic literature review. Scand J Occup Ther. 2010;17(2):101–16.

Kammerlander C, Roth T, Friedman SM, Suhm N, Luger TJ, Kammerlander-Knauer U, et al. Ortho-geriatric service--a literature review comparing different models. Osteoporosis Int. 2010;21:S637–46.

Kinley J, Froggatt K, Bennett MI. The effect of policy on end-of-life care practice within nursing care homes: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2013;27:209–20.

Kuhlmann AS, Gavin L, Galavotti C. The integration of family planning with other health services: a literature review. Int Perspect Sexual Reprod Health. 2010;36:189–96.

Laver K, Lannin NA, Bragge P, Hunter P, Holland AE, Tavender E, et al. Organising health care services for people with an acquired brain injury: an overview of systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:397. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-397.

Loader BD, Hardey M, Keeble L. Health informatics for older people: a review of ICT facilitated integrated care for older people. Int J Social Welfare. 2008;17:46–53.

Low L-F, Yap M, Brodaty H. A systematic review of different models of home and community care services for older persons. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:93. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-93.

MacAdam M. Frameworks of integrated Care for the Elderly: a systematic review: Canadian policy Repearch network, 2008.

Mackie S, Darvill A. Factors enabling implementation of integrated health and social care: a systematic review. Brit J Comm Nurs. 2016;21:82–7.

Martinez-Gonzalez NA, Berchtold P, Ullman K, Busato A, Egger M. Integrated care programmes for adults with chronic conditions: a meta-review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26:561–70.

Maslin-Prothero SE, Bennion AE. Integrated team working: a literature review. Int J Integr Care. 2010;10:e043.

Mason A, Goddard M, Weatherly H, Chalkley M. Integrating funds for health and social care: an evidence review. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2015;20(3):177–88.

McConnell T, O'Halloran P, Porter S, Donnelly M. Systematic realist review of key factors affecting the successful implementation and sustainability of the Liverpool care pathway for the dying patient. Worldviews Evidence-based Nurs. 2013;10:218–37.

Myors KA, Schmied V, Johnson M, Cleary M. Collaboration and integrated services for perinatal mental health: an integrative review. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2013;18:1–10.

Nicholson C, Jackson C, Marley J. A governance model for integrated primary/secondary care for the health-reforming first world - results of a systematic review. BMC Halth Serv Res. 2013;13:528.

Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries: 15 randomized trials. JAMA. 2009;301:603–18.

Smith E, Ross FM. Service user involvement and integrated care pathways. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2007;20(2–3):195–214.

Stewart MJ, Georgiou A, Westbrook JI. Successfully integrating aged care services: a review of the evidence and tools emerging from a long-term care program. Int J Integr Care. 2013;13:e003.

Stokes JPM, Alam R, Checkland K, Suderaghi-Sohi S, Bower P. Effectiveness of case management for ‘at risk’ patients in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132340.

Suter E, Oelke ND, Adair CE, Armitage GD. Ten key principles for successful health systems integration. Health Quart. 2009;13:16–23.

Tieman J, Mitchell G, Shelby-James T, Currow D, Fazekas B, ODoherty L, et al. Integration, coordination and multidisciplinary care: what can these approaches offer to Australian primary health care? Aust J Prim Health. 2007;13:56–65.

Trivedi D, Goodman C, Gage H, Baron N, Scheibl F, Iliffe S, et al. The effectiveness of inter-professional working for older people living in the community: a systematic review. Health Soc Care Comm. 2013;21:113–28.

Xyrichis A, Lowton K. What fosters or prevents inter-professional team-working in primary and community care? A literature review. Int J Nurs Studies. 2008;45:140–53.

Aiken LS, Butner J, Lockhart CA, Volk-Craft BE, Hamilton G, Williams FG. Outcome evaluation of a randomized trial of the PhoenixCare intervention: program of case management and coordinated care for the seriously chronically ill. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:111–26.

Battersby M, Harvey P, Mills PD, Kalucy E, Pols RG, Frith PA, et al. SA HealthPlus: a controlled trial of a statewide application of a generic model of chronic illness care. Milbank Q. 2007;85:37–67.

Béland F, Bergman H, Lebel P, Dallaire L, Fletcher J, Contandriopoulos A, et al. A system of integrated care for older persons with disabilities in Canada: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol Series A, Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:367–73.

Beland F, Bergman H, Lebel P, Dallaire L, Fletcher J, Contandriopoulos A, et al. Integrated services for frail elders (SIPA): a trial of a model for Canada. Canad J Aging. 2006;25:5–42.

Bird S, Noronha M, Sinnott H. An integrated care facilitation model improves quality of life and reduces use of hospital resources by patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic heart failure. Aust J Prim Health. 2010;16:326–33.

Bird SR, Kurowski W, Dickman GK, Kronborg I. Integrated care facilitation for older patients with complex health care needs reduces hospital demand. Austr Health Rev. 2007;31(3):451–0.

Bird SR, Noronha M, Kurowski W, Orkin C, Sinnott H. Integrated care facilitation model reduces use of hospital resources by patients with pediatric asthma. J Healthcare Qual. 2012;34:25–33.

Boult C, Leff B, Boyd CM, Wolff JL, Marstellar JA, Frick KD, et al. A matched-pair cluster-randomized trial of guided care for high-risk older patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:612–21.

Boult C, Reider L, Frey K, et al. Early effects of “guided care” on the quality of health care for multimorbid older persons: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:321–7.

Boult C, Reider L, Leff B, Boyd CM, Wolff JL. The effect of guided care teams on the use of health services: results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:460–6.

Brännström M, Boman K. Effects of person-centred and integrated chronic heart failure and palliative home care. PREFER: a randomized controlled study. Eur J Heart Failure. 2014;16:1142–51.

Brown RS, Peikes D, Peterson G, SchoreJ RCM. Six features of Medicare coordinated care demonstration programs that cut hospital admissions of high-risk patients. Health Aff. 2012;31:1156–66.

Callahan C, Boustani M, Unverzagt F, Austrom M, Damush T, Perkins A, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;295:2148–57.

Colla CH, Lewis VA, Kao LS, OMalley AJ, Chang CH, Fisher ES. Association between Medicare accountable care organization implementation and spending among clinically vulnerable beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1167–75.

Colla CH, Wennberg DE, Meara E, Skinner JS, Gottlieb D, Lewis VA, et al. Spending differences associated with the Medicare physician group practice demonstration. J Am Med Assoc. 2012;308(10):1015–23.

Counsell S, Callahan C, Clark D, Tu W, Buttar A, Stump T, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;298:2623–33.

Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Tu W, Buttar A, Stump T, et al. Cost analysis of the geriatric resources for assessment and Care of Elders care management intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1420–6.

Dorr DA, Wilcox AB, Brunker CP, Burdon RE, Donnelly SM. The effect of technology-supported, multidisease care management on the mortality and hospitalization of seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2195–202.

Ettner SL, Kotlerman J, Afifi A, Vazirani S, Hays RD, Shapiro M, et al. An alternative approach to reducing the costs of patient care? A controlled trial of the multi-disciplinary doctor-nurse practitioner (MDNP) model. Med Decision Making. 2006;26:9–17.

Fagan P, Schuster A, Boyd C, Marstellar J, Griswold M, Murphy S. Chronic care improvement in primary care: evaluation of an integrated pay-for-performance and practice-based care coordination program among elderly patients with diabetes. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:1763–82.

Farmer J, Clark M, Drewel E, Swenson T, Ge B. Consultative care coordination through the medical home for CSHCN: a randomized controlled trial. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:1110–8.

Gray D, Armstrong CD, Dahrouge S, Hogg W, Zhang W. Cost-effectiveness of anticipatory and preventive multidisciplinary team care for complex patients: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56:e20–9.

Hajewski CJ, Shirey MR. Care coordination: a model for the acute care hospital setting. J Nurs Admin. 2014;44:577–85.

Hammar T, Rissanen P, Perälä M. The cost-effectiveness of integrated home care and discharge practice for home care patients. Health Policy. 2009;92:10–20.

Hebert R, Raiche M, Dubois MF, Gueye NR, Dubuc N, Tousignant M. Impact of PRISMA, a coordination-type integrated service delivery system for frail older people in Quebec (Canada): a quasi-experimental study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65:107–18.

Hildebrandt H, Schulte T, Stunder B. Triple aim in Kinzigtal, Germany: improving population health, integrating health care and reducing costs of care -- lessons for the UK? J Integr Care. 2012;20:205–22.

Hogg W, Lemelin J, Dahrouge S, Liddy C, Amstrong CD, Legault F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of anticipatory and preventive multidisciplinary team care: for complex patients in a community-based primary care setting. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:e76–85.

Hullick C, Conway J, Higgins I, Hewitt J, Dilworth S, Holliday E, et al. Emergency department transfers and hospital admissions from residential aged care facilities: a controlled pre-post design study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:102.

Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, Greenwald JL, Sanchez GM, Johnson AE, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:178–87.

Janse B, Huijsman R, de Kuyper R Fabbricotti I. The effects of an integrated care intervention for the frail elderly on informal caregivers: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:58.

Janse B, Huijsman R, Fabbricotti I. A quasi-experimental study of the effects of an integrated care intervention for the frail elderly on informal caregivers' satisfaction with care and support. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:140.

Katon W, Russo J, Lin E, Schmittdiel J, Ciechanowski P, Ludman E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a multicondition collaborative care intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:506–14.

Martinussen M, Adolfsen F, Lauritzen C, Richardson A. Improving interprofessional collaboration in a community setting: relationships with burnout, engagement and service quality. J Interprof Care. 2012;26:219–25.

McGregor M, Lin E, Katon W. TEAMcare: an integrated multicondition collaborative care program for chronic illnesses and depression. J Ambulat Care Manag. 2011;34:152–62.

Morales-Asencio JM, Gonzalo-Jimenez E, Martin-Santos FJ, Morilla-Herrera JC, Celdran-Manas M, Carrasco AM, et al. Effectiveness of a nurse-led case management home care model in primary health care. A quasi-experimental, controlled, multi-Centre study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:193.

Olsson L-E, Hansson E, Ekman I, Karlsson J. A cost-effectiveness study of a patient-centred integrated care pathway. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65:1626–35.

Parsons M, Senior H, Kerse N, Chen MH, Jacobs S, Vanderhoorn S, et al. Should care managers for older adults be located in primary care? A randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:86–92.

Paulus A, van Raak A. The impact of integrated care on direct nursing home care. Health Policy. 2008;85:45–59.

Paulus A, van Raak A, Maarse H. Is integrated nursing home care cheaper than traditional care? A cost comparison. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45:1764–77.

Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Sint K, Lin H, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of comprehensive, integrated care for first episode psychosis in the nimh raise early treatment program. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:896–906.

Sahlen KG, Boman K, Brannstrom M. A cost-effectiveness study of person-centered integrated heart failure and palliative home care: based on a randomized controlled trial. Palliat Med. 2016;30:296–302.

Salmon RB, Sanderson MI, Walters BA, Kennedy K, Flores RC, Muney AM. A collaborative accountable care model in three practices showed promising early results on costs and quality of care. Health Aff. 2012;31:2379–87.

Stampa M, Vedel I, Buyck J, Lapointe L, Bergman H, Beland F, et al. Impact on hospital admissions of an integrated primary care model for very frail elderly patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;58:350–5.

Stewart M, Sangster JF, Ryan BL, Hoch JS, Cohen I, McWilliam CL, et al. Integrating physician Services in the Home: evaluation of an innovative program. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56:1166–74.

Taylor A, Lizzi M, Marx A, Chilkatowsky M, Trachtenberg SW, Ogle S. Implementing a care coordination program for children with special healthcare needs: partnering with families and providers. J Healthcare Qual. 2013;35:70–7.

Theodoridou A, Hengartner M, Gairing S, Jager M, Ketteler D, Kawohl W, et al. Evaluation of a new person-centered integrated care model in psychiatry. Psychiatr Quart. 2015;86:153–68.

van der Marck MA, Munneke M, Mulleners W, Hoogerwaard EM, Borm GF, Overeem S, et al. Integrated multidisciplinary care in Parkinson's disease: a non-randomised, controlled trial (IMPACT). Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:947–56.

van Gils RF, Bosmans JE, Boot CRL, Rustemeyer T, van Mechelen W, van der Valk PG, et al. Economic evaluation of an integrated care programme for patients with hand dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;69:144–52.

Wennberg DE, Marr A, Lang L, O’malley S, Bennett G. A randomized trial of a telephone care-management strategy. New England J Med. 2010;363:1245–55.

Berry LL, Rock BL, Smith Houskamp B, Brueggeman J, Tucker L. Care coordination for patients with complex health profiles in inpatient and outpatient settings. Mayo Clinic Proceed. 2013;88:184–94.

Blewett LA, Owen RA. Accountable care for the poor and underserved: Minnesota's Hennepin health model. Am J Pub Health. 2015;105:622–4.

Brawer PA, Martielli R, Pye PL, Manwaring J, Tierney A. St. Louis initiative for integrated care excellence (SLI(2)CE): integrated-collaborative care on a large scale model. Families. Systems Health. 2010;28:175–87.

Breton M, Pineault R, Levesque JF, Roberge D, Da Silva RB. Reforming healthcare systems on a locally integrated basis: is there a potential for increasing collaborations in primary healthcare? BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:262.

Brokel JM, Harrison MI. Redesigning care processes using an electronic health record: a system's experience. Joint Commission J Qual Saf. 2009;35:82–92.

Callaly T, von Treuer K, van Hamond T, Windle K. Forming and sustaining partnerships to provide integrated services for young people: an overview based on the headspace Geelong experience. Early Int Psychiatry. 2011;5:28–33.

Chen C, Garrido T, Chock D, Okawa G, Liang L. The Kaiser Permanente electronic health record: transforming and streamlining modalities of care. Health Aff. 2009;28(2):323–33.

Cohen E, Lacombe-Duncan A, Spalding K, MacInnis J, Nicholas D, Narayanan U, et al. Integrated complex care coordination for children with medical complexity: a mixed-methods evaluation of tertiary care-community collaboration. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:366.

Epstein AM, Jha AK, Orav EJ, Liebman DL, Audet A, Zezza MA, et al. Analysis of early accountable care organizations defines patient, structural, cost, and quality-of-care characteristics. Health Aff. 2014;33(1):95–102.

Fuller RL, Clinton S, Goldfield NI, Kelly WP. Building the affordable medical home. J Ambulat Care Manag. 2010;33:71–80.

Guerrero EG, Aarons GA, Palinkas LA. Organizational capacity for service integration in community-based addiction health services. Am J Pub Health. 2014;104:e40–7.

Hartgerink JM, Cramm JM, Bakker TJ, van Eijsden R, Mackenbach JP, Niebor AP. The importance of relational coordination for integrated care delivery to older patients in the hospital. J Nurs Manag. 2014;22:248–56.

Hébert R, Veil A, Raîche M, Dubois MF, Dubuc N, Tousignant M. Evaluation of the implementation of PRISMA, a coordination-type integrated service delivery system for frail older people in Québec. J Integr Care. 2008;16:4–14.

Kautz CM, Gittell JH, Weinberg DB, Lusenhop RW, Wright J. Patient benefits from participating in an integrated delivery system: impact on coordination of care. Health Care Manag Rev. 2007;32:284–94.

Khanna N, Shaya F, Chirikov V, Steffen B, DisVonk-Okhuijsen SY SD, Tjan-Heijnen VG, Verhagen AF, et al. Semination and adoption of the advanced primary care model in the Maryland multi-payer patient centered medical home program. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25:122–38.

Ouwens M, Hermens R, Termeer R, Vonk-Okhuijsen SY, Tjan-HeijnenVG VAF, et al. Quality of integrated care for patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer: variations and determinants of care. Cancer. 2007;110:1782–90.

Pineault R, Borges Da Silva R, Prud'homme A, Fournier M, Couture A, Provost S, et al. Impact of Quebec’s healthcare reforms on the organization of primary healthcare (PHC): a 2003-2010 follow-up. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:229.

Veerbeek L, van Zuylen L, Swart SJ, van der Maas PJ, de Vogel-Voogt E, van der Rijt C, et al. The effect of the Liverpool care pathway for the dying: a multi-Centre study. Palliat Med. 2008;22:145–51.

Weaver FM, Hickey EC, Hughes SL, Parker V, Fortunato D, Rose J, et al. Providing all-inclusive care for frail elderly veterans: evaluation of three models of care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:345–53.

Wedel R, Kalischuk RG, Patterson E, Brown S. Turning vision into reality: successful integration of primary healthcare in Taber, Canada. Healthcare Policy. 2007;3:80–95.

Abdul AA, Muhammad NA, Sulong S, Aljunid S. The integrated care pathway for managing post stroke (iCaPPS) patients in the community: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Value Health. 2014;17:A761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2014.08.259.

Barnett J, Vasileiou K, Djemil F, Brooks L, Young T. Understanding innovators’ experiences of barriers and facilitators in implementation and diffusion of healthcare service innovations: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:342.

Roberts L, Cameron G. Evaluation of the integrated care communities 2 Programme (incorporating the integration discovery community). Evaluation report. London: OPM Group; 2014.

Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. Primary care and accountable care — two essential elements of delivery-system reform. New England J Med. 2009;361:2301–3.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute for Health Research, within the Health Services and Delivery Research Programme [HS&DR 15/77/10].

Availability of data and materials

All available data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HS&DR Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB led the study and drafted the initial and subsequent versions of this paper, MJ and DC acted as reviewers and took part in all the study processes, AS led the literature searching, EG contributed to the data analysis, and AB contributed methodological expertise. All authors read and commented on drafts of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not required.

Consent for publication

The manuscript contains no individual person’s data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Appendix S1. Study protocol. Appendix S2. Completed PRISMA checklist. Appendix S3. Search strategy. Appendix S4. Studies excluded at full paper screening. Appendix S5. Completed quality appraisals. (DOCX 197 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Summary of studies and effect for each outcome (DOCX 335 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Baxter, S., Johnson, M., Chambers, D. et al. The effects of integrated care: a systematic review of UK and international evidence. BMC Health Serv Res 18, 350 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3161-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3161-3