Abstract

Background

Effective mentorship is an important component of medical education with benefits to all stakeholders. In recent years, conceptualization of mentorship has gone beyond the traditional dyadic experienced mentor-novice mentee relationship to include group and peer mentoring. Existing theories of mentorship do not recognize mentoring’s personalized, evolving, goal-driven, and context-specific nature. Evidencing the limitations of traditional cause-and-effect concepts, the purpose of this review was to systematically search the literature to determine if mentoring can be viewed as a complex adaptive system (CAS).

Methods

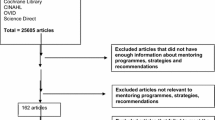

A systematic scoping review using Krishna’s Systematic Evidence-Based Approach was employed to study medical student and resident accounts of mentoring and CAS in general internal medicine and related subspecialties in articles published between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2023 in PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, ERIC, Google Scholar, and Scopus databases. The included articles underwent thematic and content analysis, with the themes identified and combined to create domains, which framed the discussion.

Results

Of 5,704 abstracts reviewed, 134 full-text articles were evaluated, and 216 articles were included. The domains described how mentoring relationships and mentoring approaches embody characteristics of CAS and that mentorship often behaves as a community of practice (CoP). Mentoring’s CAS-like features are displayed through CoPs, with distinct boundaries, a spiral mentoring trajectory, and longitudinal mentoring support and assessment processes.

Conclusion

Recognizing mentorship as a CAS demands the rethinking of the design, support, assessment, and oversight of mentorship and the role of mentors. Further study is required to better assess the mentoring process and to provide optimal training and support to mentors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Effective mentorship during medical training fosters professional development, personal growth, and ethical guidance [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. For host institutions, established mentorship programs facilitate knowledge transfer, improve recruitment and retention, and contribute to a culture of continuous learning and growth, ultimately advancing the quality of healthcare delivery and research within the organization [1,2,3,4,5, 8, 9]. Yet, despite its importance, medical education still lacks a widely accepted operational definition of mentoring [10]. Mentorship is often conflated with advising or coaching. While advisors assist trainees in making informed academic decisions and coaches provide training and guidance to help trainees reach specific goals, mentorship is a bidirectional relationship whereby an experienced mentor provides personalized guidance and support to facilitate a mentee’s development [11]. In recent years, conceptualizations of mentorship have also evolved from this traditional dyadic experienced mentor and novice mentee relationship to peer and group mentoring formats and mentoring networks [11]. Recent reviews highlight the challenges related to mentoring and attribute multiple ethical issues, including bullying, coercion, misappropriation of mentee funding and resources, and publication parasitism to inadequate structuring, support, and oversight of mentorship programs [1, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. As accounts of ethical, legal, and professional issues related to mentoring continue to grow, the need for a common understanding and consistent approach to mentoring is evident [1, 18].

Current theories of mentoring struggle to contend with mentoring’s personalized, evolving, and reciprocal nature, which is often goal-sensitive and context-specific [20, 21]. Several authors have criticized conventional models that do not recognize the dynamic relationship between mentors and mentees and the influence of external factors [11, 12]. Some studies suggest that mentoring should be considered a complex adaptive system (CAS) [22,23,24]. With such a shift in thinking likely to change the design, support, and oversight of mentoring programs, we evaluate if mentoring displays the characteristics and functions of a CAS to address our primary research question “does mentoring function as a complex adaptive system?”

Complex adaptive systems

Some authors propose that a CAS-led perspective better captures mentoring’s non-linear, diverse, individualized, and unpredictable interrelationships [25]. A CAS is a system composed of many interacting and interdependent components (agents), whereby one agent’s actions can change the context for the others [26]. Features of CAS include complexity, adaptation, non-linearity, and self-organization, resulting in the spontaneous emergence of new and unpredictable patterns, behaviors, and trajectories. We define these features throughout the manuscript and summarize the terms in Table 1 as characterized by Ellis et al. [27] and Gear et al. [28].

Methods

Theoretical lens

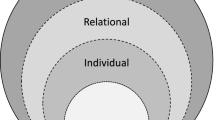

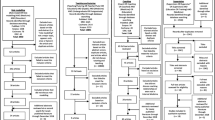

A mentoring ecosystem encompasses a broad range of mentors, mentees, and stakeholders, including institutions, all contributing to individual growth and development through mentorship. The concept of the mentoring ecosystem is like a Community of Practice, or a social network with mutual experiences and values [29], and is shaped around a predetermined course from marginal participation at the periphery of the mentoring program to a more central role within the mentoring program [29] (Fig. 1). This mentoring trajectory is framed on mentoring stages [30, 31], or clearly delineated phases of the mentoring process. Transitions from one stage to another create ideal assessment points, which in turn, inform the longitudinal mentoring support system, or mentoring umbrella. The mentoring umbrella is a framework where multiple forms of mentoring and support, including supervision, coaching, tutoring, instruction, and teaching, are provided to support an individual’s growth and development, like how an umbrella provides protection and coverage [32]. This approach ensures that mentees receive comprehensive support from different sources to enhance their learning, skill development, and career advancement [32]. The combination of the mentoring trajectory and mentoring umbrella creates the mentoring tube, which guides mentoring progress.

Mentoring ecosystem. The yellow circles represent the mentee’s microenvironment while the blue circles symbolize other stakeholders’ microenvironments. The dark green spiral represents the mentoring tube, and the thin blue lines represent the changing course of the mentoring relationship along the mentoring trajectory. The mentoring trajectory is framed around key stages of development. Some of these stages are highlighted. The mentoring trajectory is not depicted as a smooth course underlining the inevitable changes apparent across the mentoring stages

SEBA review methodology

Using Krishna’s Systematic Evidence-Based Approach (SEBA) to guide our scoping review [32,33,34,35], we explore mentoring in medical education as a sociocultural construct shaped by multiple stakeholder and host organization-related factors. This approach also accommodates the CAS lens through which we evaluate the different aspects of mentoring for features of CAS. SEBA is a methodologic framework for conducting systematic scoping reviews. The steps of the SEBA process involve: (1) a systematic approach whereby teams of medical education experts and researchers agree upon the research questions, search terms, and databases to be included; (2) the split approach in which a research team conducts inductive thematic analysis of the included articles allowing themes to emerge from the data while other research team(s) independently use a predefined set of codes to guide the analysis and identify themes; (3) the jigsaw perspective involves combining overlapping and complementary themes to create larger categories of themes; (4) a comparison process with the features of CAS ensures that relevant themes are not omitted; (5) analysis of data and non-data driven literature compares the themes derived from evidenced-based publications with those from non-data-based articles (editorials, grey literature, letters, opinion pieces, and perspectives) for similarity to ensure that the non-data-based articles do not bias the analysis; and (6) synthesis where the derived themes create the domains that inform the discussion (Fig. 2).

Reflexivity

The research team consisted of medical students and research assistants, guided by Internal Medicine and Palliative Care consultants, with expertise in medical education, qualitative analysis, and conducting systematic reviews. The medical students were members of a peer-mentorship research program; their personal experiences influenced the study design and data interpretation. To provide a balanced review, an expert team comprising of a librarian from the National University of Singapore’s (NUS) Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM) and local educational experts and clinicians at YLLSoM, National Cancer Centre Singapore, Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, and Duke-NUS Medical School guided the 6-stages of the SEBA process. The teams also engaged in personal and group reflexivity throughout the process to minimize the impact of personal experience bias.

Stage 1: systematic approach

This SEBA-systematic scoping review is guided by the PRISMA-P checklist to ensure a reproducible and robust mapping of current notions of mentoring.

Identifying the research question

Guided by the expert team, the research team determined the primary research question to be: “does mentoring function as a complex adaptive system?” The secondary research question is: “what characteristics of CAS are evident in mentoring?”

Inclusion criteria

A population, concept, context (PCC) study design format was adopted to guide the research [36] (Table 2). We included all study types (quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods) and non-empirical manuscripts (perspectives, editorials, letters) involving medical students and medical trainees and physicians in Internal Medicine and its related subspecialties. We excluded studies from other disciplines and those involving mentorship by patients or interdisciplinary mentors, along with studies dealing with supervision, coaching, role-modeling, advising, or sponsorship. In keeping with Pham et al.’s [37] recommendations on sustaining the research process and accommodating existing manpower and time constraints, the research team restricted the searches to articles published between 1st January 2000 and 31st December 2023.

Database searching

Eleven members of the research teams searched five bibliographic databases (PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CINAHL, Scopus) between 13 February 2023 and 20 April 2024 (Table 3). The research teams, each comprised of medical students and a senior reviewer, independently carried out the searches. The search terms and strategies used for database searching are detailed in Appendix 1.

Extracting and charting the data

Each group independently reviewed the abstracts and titles and discussed their findings at online meetings where Sandelowski and Barroso [148]’s ‘negotiated consensual validation’ was used to achieve consensus on the final list of full-text articles to be reviewed. Data extracted from each manuscript meeting inclusion criteria included the author, year of publication, study type, study population, study location, components of the mentorship ecosystem, including mentoring approach/theories, stakeholders, mentoring structure and relationships, environment and external influences, and main findings of the study. The characteristics of all included studies are listed in Appendix 1.

Stage 2: Split approach

Krishna’s ‘Split Approach’ [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151] was employed to enhance the reliability of the data analyses. This approach involves the research team dividing (or ‘splitting’) into different groups to independently analyze the manuscripts. This concurrent analysis enables review of data from different perspectives while also aiming to reduce omission of new findings or negative reports. For this review, three groups of researchers independently analyzed the included articles. Using best practices, the first team summarized and tabulated the included full-text articles [152, 153] (Appendix 1). Concurrently, the second team analyzed the included articles using Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis [154]. A third team of researchers employed Hsieh and Shannon’s [155] approach to directed content analysis to analyze the included articles using pre-determined codes drawn from several published manuscripts on mentorship in medical education [7, 156, 157]. These studies were chosen because they provide the most recent review of mentoring practice at the time of this review [7] and offer the most recent longitudinal work on the subject [156, 157].

Stage 3: Jigsaw perspective

In keeping with SEBA’s iterative process, the themes were reviewed by the expert and research teams. Overlaps between the themes were viewed as pieces of a jigsaw puzzle with the intention of combining overlapping or complementary pieces to create a bigger piece of the puzzle to form larger categories of themes.

Stage 4: Comparison

Comparisons of the themes were made with the features of CAS identified by Ellis et al. [27] and Gear et al. [28], specifically multiple agents, self-organizing networks, co-evolution, system adaptation, non-linearity, feedback loops, emergence, boundaries, path dependency, and ‘far from equilibrium (Table 1). This step ensures that important themes were not omitted.

Results

The PRISMA diagram illustrates the process (Fig. 3). Of 5,704 abstracts reviewed, 134 full-text articles were evaluated, and 216 articles were included (additional articles included following snowballing, or review of the references of included articles). The themes elicited during thematic analysis of all 216 manuscripts were overlapped and combined (jigsaw approach) into larger categories of themes and compared with features of CAS to create 2 domains, namely mentoring relationships and mentoring programs, each with sub-themes as detailed below.

Domain 1. Mentoring relationships

Mentoring relationships are influenced by the various stakeholders (agents) and the mentoring process.

Multiple stakeholders (agents)

A key feature of CAS is the presence of multiple agents interacting within collaborative networks [27, 28, 30, 158,159,160]. Our results support that mentors, mentees, institutional leaders, and multiple other stakeholders interact within the mentorship ecosystem by exchanging resources and information, thereby influencing each other’s perspectives and behaviors and collectively shaping the trajectory and outcomes of the mentorship dynamic. Several authors explored the roles of mentors, peer-mentors, mentees, and the host organization in mentoring programs and noted that the nature of collaborative networks can be a mix of formal and informal approaches [7, 161,162,163,164,165,166]. Even within formal programs [30, 167,168,169,170], with their clearly defined roles and responsibilities, expectations, and codes of conduct, the presence of multiple agents, each with their roles, goals, responsibilities, and areas of interest, suggests that interactions may veer toward the informal. Such variation draws attention shifting nature of the relationships between different stakeholders throughout a mentorship.

Similarly, stakeholder influence on mentees varies according to the circumstances and time. Some studies described fluidity in the nature of interactions between stakeholders, suggesting that membership in the mentoring relationship can change [7, 34, 157, 163]. New members may replace those who have completed their respective tasks, while other members may leave and re-enter the mentoring program at different points with different roles and responsibilities and varying levels of participation. Re-forming and adjusting mentoring relationships between new and returning stakeholders introduces more complexity. In addition, medical education’s hierarchical nature also impacts mentoring interactions and relationships, particularly when considering evolving circumstances and changing goals, expectations, and timelines.

The presence of multiple agents highlights the bilateral, but not necessarily equal, impact that mentoring relationships have on individual members. Stakeholder views and responses to their mentoring experiences are influenced by multiple factors, including their personal belief systems, developing competencies, coping strategies, psycho-emotional state, and maturing relationships with other stakeholders. Concurrently, the agent’s conduct, actions, and motivations are also influenced by contextual considerations, including changes to their professional roles and responsibilities, as well as stage-specific modifications to the curricula, host organization-related factors, mentoring culture, and access to support (Table 3).

Mentoring structures

The process, or structures (7, 49, 56, 60–63), of mentoring play a key role in shaping mentoring relationships [168, 171, 172]. We use Krishna et al.’s [6] concept of the mentoring ecosystem to illustrate the role that mentoring stages, mentoring trajectory, mentoring environment, mentoring umbrella, and the mentoring approach have on the CAS-related concepts of path dependency, boundaries, and adaptations in mentoring relationships [47].

Path dependency

Current concepts of path dependency [165, 173, 174] focus on the impact of past experiences or trajectories [7] on the current and future state of the system, suggesting that the cumulative effects of individual and programmatic experiences within the system have an enduring impact on its current structure and future potential [27, 28, 159]. Path dependency acknowledges that previous mentorship experiences [158, 175], historical choices [170] made by mentors and mentees, and the development of mentoring structures can shape the current dynamics and long-term possibilities of mentoring relationships. The impact of many of these effects is managed through the alignment of expectations [171] and available support.

Boundaries

Boundaries in CAS represent sociocultural constructs that highlight points of contact with other entities. Mentorship programs often span multiple levels of organization, including individual, interpersonal, institutional, and societal levels. These ‘fuzzy boundaries’ surrounding the micro-environments of each stakeholder [176] underscore the connections that influence the environment and adjacent micro-environments, adding another layer of complexity to the system and influencing the types of outcomes that can be achieved. The impact of these changes on the micro-environment depends on various factors, including the nature and duration of the mentoring relationship, the seniority, roles [166], and motivations of the stakeholders, the roles and expectations [170, 177] within the specific stages of mentoring, and the support provided by the mentoring umbrella [33, 35, 157, 178]. Moreover, the ‘fuzzy boundaries’ also enable the mentoring umbrella to shape micro-environments by providing timely and appropriate feedback, support, and remediation along the mentoring trajectory.

System adaptation

System adaptation refers to a system’s ability to modify itself to maintain stability, optimize performance, or achieve objectives despite disturbances [27, 28]. Within CAS, adaptations [179] are made to avoid major changes [180] to the system. Here, adaptability hinges on finding a balance between flexibility and consistency [7], focusing on making the smallest possible changes to the least significant elements to facilitate meaningful changes within the evolving micro-environments along the mentoring trajectory. In the mentoring ecosystem [181], the aim is to prioritize changes at the individual level and among a select few stakeholders [158, 176] to preserve stability in the broader program [182] while nurturing the mentorship process.

Co-evolution

Within CAS, interactions between agents give rise to mutual transformations [171, 183, 184]. As mentees adapt to the different goals, roles, and situated learning requirements across distinct mentoring stages along the mentoring trajectory, their interactions with other stakeholders [163] lead to changes in these stakeholders. This co-evolution is focused on preserving the quality of interactions within their mentoring relationship, referred to as mentoring dynamics. These dynamics are pivotal in shaping the personalized and enduring mentoring relationships that underpin mentoring success [6, 185, 186]. For example, as a mentee gains confidence and skills through effective feedback, the mentor can gain valuable insights to improve communication and feedback practices.

Feedback loops

Reflections on new mentoring experiences [171, 180], adaptations, and co-evolutions serve to reinforce positive changes while mitigating the repercussions of negative changes. This recursive influence of feedback loops also extends to thought processes, decision-making, and future actions [33, 35, 157, 168, 178, 187].

Emergence

The processes of adaptation [176], co-evolution, and feedback loops [163] give rise to the concept of ‘emergent behavior,’ behavior that emerges from interactions within the system, often focused on sustaining specific goals [27, 28]. ‘Emergent behaviour’ is shaped by the prevailing conditions, available resources and options, guidance received, and stakeholder interpretation of unfolding events.

Self-organization

When individuals experience shifts in their attitudes, thinking [32, 188], practice, and belief systems in response to ongoing changes, feedback, and environmental shifts, self-organization occurs. The mentoring framework, development of competencies [189], coping strategies, meaning-making process, and psycho-emotional state of individuals are pivotal in shaping self-organization within their micro-environment. These transformations in thoughts, emotions, and practices are guided by regnant standards [1, 7, 151, 190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201].

Self-organization subsequently influences the mentoring trajectory. When these changes align with mentoring objectives and approach, and are consistent with the overall trajectory, they facilitate goal attainment. However, if the trajectory deviates from alignment with these elements, mentees may struggle to reach their goals.

Non-linearity

This evolving membership [158, 171, 180, 202] of mentoring programs set within a hierarchical environment characterized by differences in diversity [174, 203,204,205,206], gender [206, 207], seniority, roles, and responsibilities [7, 163], coupled with adaptations, co-evolution, and the emergence of new behaviours, lead to non-linear responses [32, 164, 170] in interactions among stakeholders with diverse roles and responsibilities. This non-linearity [156, 159, 163, 208] is also apparent in the way individuals respond to various stimuli [1, 18, 33, 35, 95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210].

Far from equilibrium

The evolving processes [173] of adaptations [211], co-evolution, emergent behaviour, self-organization, non-linearity, and the influence of feedback loops [163, 187] expose a system in a state ‘far from equilibrium’ [27, 28], highlighted further during the COVID-19 pandemic [158, 212, 213] .In this context, even minor changes can lead to disproportionate impacts on mentoring relationships and processes [1, 7, 18, 21, 29, 35, 95, 156, 198, 210, 214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221]. In mentorship, being ‘far from equilibrium’ can also suggest a state of continuous learning, growth, and innovation, where mentor and mentees interactions are dynamic, challenging existing norms and practices and creating new possibilities for personal and professional development.

Domain 2. Mentoring programs

Mentoring programs [30, 169, 179, 210, 212, 222,223,224,225,226,227] are often integrated [188, 208, 228] within the formal curriculum [7] and subject to oversight [176, 229] and evaluation by the host organization [53, 156, 230]. The increased emphasis on oversight within mentorship has grown amidst mounting concerns about ethical issues in mentoring [1, 12, 14,15,16,17,18,19]. While mentoring programs allow for a degree of flexibility, adaptability, and responsiveness, these functions are constrained by host organization-related factors and standards [231]. There are concerted efforts to instil consistency into practice, as evident in the structuring of the mentoring trajectory through the mentoring framework, the personalization of mentoring experiences, support, and assessments [189], and the establishment of clear transition points from one mentoring stage to the next, ensuring that the required knowledge, skills [232], and competencies for progression have been acquired. Furthermore, there is an emphasis on establishing clear expectations [233, 234] for the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders at each stage, particularly in light of their differing roles along the mentoring trajectory and maintaining clear standards for their engagement [202] as some stakeholders move in and out of various mentoring stages.

Moreover, mentoring programs can also establish clear areas of interest, goals, expectations, timelines, and entry criteria [210]. The mentoring project, setting, structure, and the faculty involved also help distinguish the mentoring process from other mentoring projects [38]. For example, the Palliative Medicine Initiative (PMI), as described by Krishna and colleagues, represents a structured research mentoring program jointly established within the Division of Supportive and Palliative Care and the Centre for Biomedical Ethics at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine at the University of Singapore. Comprised mainly of palliative care physicians and ethicists as mentors, the PMI is framed as a unique research-oriented mentoring program, with a specific focus on ethics and palliative care research.

Several authors frame mentoring projects in medical education as a community of practice (CoP). In CoPs, learning is a collaborative and social process. The unique nature of each mentoring project, with its specific inclusion and exclusion criteria [188], focal points, approaches, and distinct project boundaries underlie the notion that each project functions as a CoP. As most programs host more than one mentoring project, the mentoring program can be viewed as a landscape of practice (LoP), a complex tapestry of various CoPs [199, 235,236,237,238,239,240]. This view of mentoring programs as LoPs is supported by recent studies [156, 157], which reveal complexities within the mentoring process that arise when members of the host organization, mentors, or peer mentors engage in more than one project or CoP simultaneously, leading to a situation in which events or adaptations in one project can not only affect stakeholders in other CoPs but, perhaps more importantly, can also impact the nature and quality of their mentoring relationships in other projects within the LoP [156].

Stage 5: analysis of evidence-based and non-data driven literature

Evidenced-based data from bibliographic databases were separated from grey literature and opinion, perspectives, editorials, letters, and non-data-based articles drawn from bibliographic databases and both groups were thematically analysed separately. The themes from both groups were compared to determine if there were additional themes in the non-data-driven group that could influence the narrative. There was consensus from the research team that themes from non-data-driven and peer-reviewed evidence-based publications were similar and did not bias the analysis.

Discussion

Stage 6: synthesis

In answering the research question “what characteristics of CAS are evident in mentoring?”, this review highlights how mentoring relationships involve multiple stakeholders and exhibit CAS-like features, such as emergence, adaptability, self-organization, co-evolution, non-linearity, path dependency, and a state far-from-equilibrium. These dynamics highlight the unpredictable and nonlinear nature of mentorship. However, traditional views of mentoring relationships impose rigid boundaries and predefined trajectories, akin to CoPs, which can stifle the natural evolution and complexity of mentoring relationships. The data challenge us to rethink how we define and approach mentorship, emphasizing the need to embrace its adaptability and self-organizing nature. They suggest that by acknowledging and leveraging the CAS-like characteristics of mentorship, we can foster more innovative and effective mentoring processes.

Our findings also emphasize that efforts to guide the mentoring process can occur at all stages of this journey. This is evident in how emergent behavior, adaptations, co-evolution, and self-organization are influenced by many host organization-related factors and are incorporated within professional codes of conduct, ethical standards, and organizational expectations. These features underscore the need for a more nuanced CAS-based theory to describe mentoring relationships and the factors that impact them. Adapting a resilience framework, or a model that emphasizes the capacity of systems to absorb disturbances, adapt to changing conditions, and maintain core functions [241], for example, to the context of CAS and mentorship in medical education can provide a different perspective on the dynamic and non-linear nature of mentorship relationships and how they can be influenced by factors such as feedback loops, emergence, self-organization, and adaptation. Ultimately, this can promote more supportive and sustainable approaches to mentoring to better address the diverse and evolving needs of mentees.

Our findings have several curricular and policy implications. First, given the multiple agents involved and the unpredictable nature of mentoring relationships [27, 28], mentoring programs should be embedded within a formal framework. This structure allows the host organization to establish clear guidelines and align expectations, timelines, and support. Moreover, it promotes consensus on the mentoring approach, structure, trajectory, and stages. Within this formal structure, accessible, longitudinal training opportunities should be established. Communication, assessment, and support systems for all stakeholders can also be put in place to create an environment that is conducive to effective mentoring, thereby minimizing path dependency, or the impact of historical decisions or biases [27, 28]. As mentorship relationships are non-linear whereby small changes can have a disproportionate impact on the mentee’s development and career trajectory [27, 28], the host organization should take an active role in supporting mentor training and conducting regular assessments of individual projects and the program as a whole. This is particularly important as mentoring is recognized as a proactive process that relies on the involvement of mentoring faculty. This also acknowledges co-evolution in mentorship and supports bidirectional growth and learning between mentors and mentees. Formal recognition of mentor contributions is warranted, along with the allocation of protected time from clinical service to ensure that mentors can effectively meet their mentoring obligations.

To mitigate the risks and biases of path dependency [27, 28], host organizations should evaluate institutional practices that may be influenced by historical factors and biases and conduct comprehensive, longitudinal assessments of the stakeholders, their mentoring relationships, progress, development, the program environment, structure, and approach. As part of this process, the use of mentoring diaries can provide a better understanding of mentee and mentor experiences over time and changing situations. Additionally, mentoring portfolios can provide multisource feedback and evidence of research, clinical, and professional development.

Limitations

Analysis of literature on mentoring programs in medical schools is largely drawn from North American and European practices, possibly limiting generalizability to non-Western settings. We limited the search to studies involving medical students and residents in internal medicine and related sub-specialties. Mentoring experiences of surgical and other non-medical specialty residents may be different. While introducing perspective data gives insights into the initiation and development of mentoring programs, selection or reporting bias may be introduced. Further, the applicability of the findings in other healthcare settings may be compromised by conflations of mentoring in clinical and non-clinical settings.

Conclusion

The literature supports the resemblance between mentorship and complex adaptive systems, highlighting the dynamic, emergent, and nonlinear nature of mentoring relationships, while advocating for a paradigm shift towards more supportive and efficient mentorship practices in medical education. Further study of the environments and boundaries of mentoring relationships are needed to guide our evolving perspective of mentoring.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

- CAS:

-

Complex Adaptive System

- SEBA:

-

Systematic Evidence-Based Approach

- PCC:

-

Population, Concept Context

- PIF:

-

Professional Identity Formation

- CoP:

-

Community of Practice

- LoP:

-

Landscape of Practice

References

Cheong CWS, Chia EWY, Tay KT, Chua WJ, Lee FQH, Koh EYH, et al. A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in internal medicine, family medicine and academic medicine. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2020;25(2):415–39.

Choo Hwee P, Hwee Sing K, Yong Hwang MK, Hum Yin Mei A. A qualitative study on the experiences and reflections of junior doctors during a palliative care rotation: perceptions of challenges and lessons learnt. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(3):549–e558541.

Aslakson R, Kamal A, Gelfman L, Mazanec P, Morrison RS, Ferrell B, et al. Are you my mentor? A panel discussion featuring an all-star cast of AAHPM and HPNA mentors and mentees (th319). J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(2):342–3.

Zhukovsky DS, Bruera E, Rajagopal MR, Rodin G. B07-B building the future of palliative care: Mentoring our people. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(6):e18–9.

Defilippi KM, Cameron S. Promoting the integration of quality palliative care: the South African mentorship program. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(5):552–7.

Krishna LKR, Tan LHE, Ong YT, Tay KT, Hee JM, Chiam M, et al. Enhancing mentoring in palliative care: an evidence based mentoring framework. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520957649–2382120520957649.

Goh S, Wong RSM, Quah ELY, Chua KZY, Lim WQ, Ng ADR et al. Mentoring in palliative medicine in the time of COVID-19: A systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):Article 359.

Carey EC, Weissman DE. Understanding and finding mentorship: a review for junior faculty. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(11):1373–9.

Kashiwagi DT, Varkey P, Cook DA. Mentoring programs for physicians in academic medicine: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88(7):1029–37.

Jacobi M. Mentoring and undergraduate academic success: a literature review. Rev Educ Res. 1991;61(4):505–32.

Ramani S, Kusurkar RA, Lyon-Maris J, Pyorala E, Rogers GD, Samarasekera DD et al. Mentorship in health professions education - an AMEE guide for mentors and mentees: AMEE guide 167. Med Teach. 2023:1–13.

Singh T, Singh A. Abusive culture in medical education: mentors must mend their ways. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2018;34(2):145–7.

Mahmoudi M. The need for a global committee on academic behaviour ethics. Lancet. 2019;394(10207):1410.

Abu-Zaid A. Protecting medical students against workplace research bullying: a graduate’s experience and standpoint. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2020;33(2):79–80.

Olaussen A, Reddy P, Irvine S, Williams B. Peer-assisted learning: time for nomenclature clarification. Med Educ Online. 2016;21(1):30974–8.

Gray K, Annabell L, Kennedy G. Medical students’ use of Facebook to support learning: insights from four case studies. Med Teach. 2010;32(12):971–6.

Klarare A, Hansson J, Fossum B, Fürst CJ, Lundh Hagelin C. Team type, team maturity and team effectiveness in specialist palliative home care: an exploratory questionnaire study. J Interprof Care. 2019;33(5):504–11.

Kow CS, Teo YH, Teo YN, Chua KZY, Quah ELY, Kamal NHBA, et al. A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):Article246.

Kwok LS. The white bull effect: abusive coauthorship and publication parasitism. J Med Ethics. 2005;31(9):554–6.

Yeam CT, Wesley LTW, Margaret EHF, Kanesvaran R, Krishna LKR. An evidence-based evaluation of prevailing learning theories on mentoring in palliative medicine. Palliat Med Care. 2016;3(1):1–7.

Wesley L, Ikbal M, Wu J, Wahab M, Yeam C. Towards a practice guided evidence based theory of mentoring in palliative care. J Palliat Care Med. 2017;7(296):2.

Jones R, Brown D. The mentoring relationship as a complex adaptive system: finding a model for our experience. Mentor Tutoring: Partnersh Learn. 2011;19(4):401–18.

Jones R, Corner J. Seeing the forest and the trees: a complex adaptive systems lens for mentoring. Hum Relat. 2012;65(3):391–411.

Woodruff JN. Accounting for complexity in medical education: a model of adaptive behaviour in medicine. Med Educ. 2019;53(9):861–73.

Smith PA, Palmberg K. Complex adaptive systems as metaphors for organizational management. Learn Organ. 2009;6(16).

Mennin S. Self-organisation, integration and curriculum in the complex world of medical education. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):20–30.

Ellis B, Herbert S. Complex adaptive systems (cas): an overview of key elements, characteristics and application to management theory. Inf Prim Care. 2011;19:33–7.

Gear C, Eppel E, Koziol-McLain J. Advancing complexity theory as a qualitative research methodology. Int J Qual Methods. 2018;17:1–10.

Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185–91.

Haas DM, Hadaie B, Ramirez M, Shanks AL, Scott NP. Resident research mentoring teams: a support program to increase resident research productivity. J Grad Med Educ. 2023;15(3):365–72.

Ravishankar M, Areti A, Kumar VR, Rani TS, Ananthakrishnan P. Competency-based postgraduate training: mentoring and monitoring using entrustable professional activities with descriptive rubrics for objectivity— a step beyond Dreyfus. Natl Med J India. 2024;36(3):176–81.

Toh RQE, Koh KK, Lua JK, Wong RSM, Quah ELY, Panda A et al. The role of mentoring, supervision, coaching, teaching and instruction on professional identity formation: A systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):Article 531.

Lim JY, Ong SYK, Ng CYH, Chan KLE, Wu SYEA, So WZ et al. A systematic scoping review of reflective writing in medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):Article 12.

Tay KT, Tan XH, Tan LHE, Vythilingam D, Chin AMC, Loh V, et al. A systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of interprofessional mentoring in medicine from 2000 to 2019. J Interprof Care. 2021;35(6):927–39.

Teo KJH, Teo MYK, Pisupati A, Ong RSR, Goh CK, Seah CHX, et al. Assessing professional identity formation (PIF) amongst medical students in oncology and palliative medicine postings: a SEBA guided scoping review. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21(1):Article200.

Osama T, Brindley D, Majeed A, Murray KA, Shah H, Toumazos M, et al. Teaching the relationship between health and climate change: a systematic scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):e020330.

Pham MT, Rajic A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85.

Keating JA, Jasper A, Musuuza J, Templeton K, Safdar N. Supporting midcareer women faculty in academic medicine through mentorship and sponsorship. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2022;42(3):197–203.

Crampton PES, Afzali Y. Professional identity formation, intersectionality and equity in medical education. Med Educ. 2021;55(2):140–2.

Wyatt TR, Balmer D, Rockich-Winston N, Chow CJ, Richards J, Zaidi Z. Whispers and shadows’: a critical review of the professional identity literature with respect to minority physicians. Med Educ. 2021;55(2):148–58.

Chow CJ, Byington CL, Olson LM, Ramirez KPG, Zeng S, López AM. A conceptual model for understanding academic physicians’ performances of identity: findings from the University of Utah. Acad Med. 2018;93(10):1539–49.

Ong E, Krishna L. Perspective from Singapore. NUS; 2014.

Ong E, Krishna L, Neo P. The sociocultural and ethical issues behind the decision for artificial hydration in a young palliative patient with recurrent intestinal obstruction. Ethics Med. 2015;31(1):39–51.

Surbone A, Baider L. Personal values and cultural diversity. J Med Person. 2013;11(1):11–8.

Au A. Online physicians, offline patients. Int J Sociol Soc Policy. 2018;38(5–6):474–83.

Al-Abdulrazzaq D, Al-Fadhli A, Arshad A. Advanced medical students’ experiences and views on professionalism at Kuwait University. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):Article150.

Kavas MV, Demirören M, Koşan AMA, Karahan ST, Yalim NY. Turkish students’ perceptions of professionalism at the beginning and at the end of medical education: a cross-sectional qualitative study. Med Educ Online. 2015;20(1):26614.

Byszewski A, Hendelman W, McGuinty C, Moineau G. Wanted: role models - medical students’ perceptions of professionalism. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12(1):115.

Smith SE, Tallentire VR, Cameron HS, Wood SM. The effects of contributing to patient care on medical students’ workplace learning. Med Educ. 2013;47(12):1184–96.

Kenny NP, Mann KV, MacLeod H. Role modeling in physicians’ professional formation: reconsidering an essential but untapped educational strategy. Acad Med. 2003;78(12):1203–10.

Rosenblum ND, Kluijtmans M, Ten Cate O. Professional identity formation and the clinician–scientist: a paradigm for a clinical career combining two distinct disciplines. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):1612–7.

Meyer EM, Zapatka S, Brienza RS. The development of professional identity and the formation of teams in the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System’s Center of Excellence in Primary Care Education Program (CoEPCE). Acad Med. 2015;90(6):802–9.

Birden H, Glass N, Wilson I, Harrison M, Usherwood T, Nass D. Teaching professionalism in medical education: a best evidence medical education (BEME) systematic review. BEME Guide 25 Med Teach. 2013;35(7):e1252–1266.

Gilligan C, Loda T, Junne F, Zipfel S, Kelly B, Horton G, et al. Medical identity; perspectives of students from two countries. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):Article420.

Wang XM, Swinton M, You JJ. Medical students’ experiences with goals of care discussions and their impact on professional identity formation. Med Educ. 2019;53(12):1230–42.

Witman Y. What do we transfer in case discussions? The hidden curriculum in medicine…. Perspect Med Educ. 2014;3(2):113–123.

Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 1994;69(11):861–71.

Whitehead C, Kuper A, Freeman R, Grundland B, Webster F. Compassionate care? A critical discourse analysis of accreditation standards. Med Educ. 2014;48(6):632–43.

Seoane L, Tompkins LM, De Conciliis A, Boysen PG. Virtues education in medical school: the foundation for professional formation. Ochsner J. 2016;16(1):50–5.

Gaufberg E, Bor D, Dinardo P, Krupat E, Pine E, Ogur B, et al. In pursuit of educational integrity: Professional identity formation in the Harvard Medical School Cambridge Integrated Clerkship. Perspect Biol Med. 2017;60(2):258–74.

Monrouxe LV. Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care? Med Educ. 2010;44(1):40–9.

Chuang AW, Nuthalapaty FS, Casey PM, Kaczmarczyk JM, Cullimore AJ, Dalrymple JL et al. To the point: Reviews in medical education - taking control of the hidden curriculum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):316.e311-316.e316.

Kay D, Berry A, Coles NA. What experiences in medical school trigger professional identity development? Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(1):17–25.

Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1185–90.

Frost HD, Regehr G. I am a doctor: negotiating the discourses of standardization and diversity in professional identity construction. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1570–7.

MacLeod A. Caring, competence and professional identities in medical education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Prac. 2011;16(3):375–94.

Rodríguez C, López-Roig S, Pawlikowska T, Schweyer FX, Bélanger E, Pastor-Mira MA, et al. The influence of academic discourses on medical students’ identification with the discipline of family medicine. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):660–70.

Warmington S, McColl G. Medical student stories of participation in patient care-related activities: the construction of relational identity. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Prac. 2017;22(1):147–63.

Foster K, Roberts C. The heroic and the villainous: a qualitative study characterising the role models that shaped senior doctors’ professional identity. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):Article206.

Hendelman W, Byszewski A. Formation of medical student professional identity: categorizing lapses of professionalism, and the learning environment. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):Article139.

Sternszus R, Boudreau JD, Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Macdonald ME, Steinert Y. Clinical teachers’ perceptions of their role in professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2020;95(10):1594–9.

Jarvis-Selinger S, MacNeil KA, Costello GRL, Lee K, Holmes CL. Understanding professional identity formation in early clerkship: a novel framework. Acad Med. 2019;94(10):1574–80.

Sadeghi Avval Shahr H, Yazdani S, Afshar L. Professional socialization: an analytical definition. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2019;12(17).

Brody H, Doukas D, Professionalism. A framework to guide medical education. Med Educ. 2014;48(10):980–7.

Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: a guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):718–25.

Irby DM, Hamstra SJ. Parting the clouds: three professionalism frameworks in medical education. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):1606–11.

Huda N, Faden L, Wilson CA, Plouffe RA, Li E, Saini MK et al. The ebb and flow of identity formation and competence development in sub-specialty residents: study of a continuity training setting. [Preprint]. 2020.

Remmen R, Denekens J, Scherpbier A, Hermann I, van der Vleuten C, Royen PV, et al. An evaluation study of the didactic quality of clerkships. Med Educ. 2000;34(6):460–4.

Wearne SM, Butler L, Jones JA. Educating registrars in your practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2016;45(5):274–7.

Balmer DF, Serwint JR, Ruzek SB, Giardino AP. Understanding paediatric resident-continuity preceptor relationships through the lens of apprenticeship learning. Med Educ. 2008;42(9):923–9.

Leeuw J-VD, Buwalda HGAR, Wieringa-De Waard N, Van Dijk M. Learning from a role model: a cascade or whirlpool effect? Med Teach. 2015;37(5):482–9.

Lightman E, Kingdon S, Nelson M. A prolonged assistantship for final-year students. Clin Teach. 2015;12(2):115–20.

Nirodi P, El-Sayeh H, Henfrey H. Applying the apprenticeship model to psychiatry: an evaluation. Prog Neurol Psychiatry. 2018;22(1):25–9.

Ratanawongsa N, Teherani A, Hauer KE. Third-year medical students’ experiences with dying patients during the internal medicine clerkship: a qualitative study of the informal curriculum. Acad Med. 2005;80(7):641–7.

Dréano-Hartz S, Rhondali W, Ledoux M, Ruer M, Berthiller J, Schott A-M, et al. Burnout among physicians in palliative care: impact of clinical settings. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14(4):402–10.

Koh MYH, Hum AYM, Khoo HS, Ho AHY, Chong PH, Ong WY, et al. Burnout and resilience after a decade in palliative care: what survivors have to teach us. A qualitative study of palliative care clinicians with more than 10 years of experience. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(1):105–15.

Lehto RH, Heeter C, Forman J, Shanafelt T, Kamal A, Miller P, et al. Hospice employees’ perceptions of their work environment: a focus group perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):6147.

Koh MYH, Chong PH, Neo PSH, Ong YJ, Yong WC, Ong WY, et al. Burnout, psychological morbidity and use of coping mechanisms among palliative care practitioners: a multi-centre cross-sectional study. Palliat Med. 2015;29(7):633–42.

Back AL, Steinhauser KE, Kamal AH, Jackson VA. Building resilience for palliative care clinicians: an approach to burnout prevention based on individual skills and workplace factors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(2):284–91.

Kavalieratos D, Siconolfi DE, Steinhauser KE, Bull J, Arnold RM, Swetz KM, et al. “It is like heart failure. It is chronic...And it will kill you”: A qualitative analysis of burnout among hospice and palliative care clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53(5):901–910.e901.

Ercolani G, Varani S, Peghetti B, Franchini L, Malerba MB, Messana R, et al. Burnout in home palliative care: what is the role of coping strategies? J Palliat Care. 2020;35(1):46–52.

Tan BYQ, Kanneganti A, Lim LJH, Tan M, Chua YX, Tan L, et al. Burnout and associated factors among health care workers in Singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(12):1751–e17581755.

Dijxhoorn A-FQ, Brom L, van der Linden YM, Leget C, Raijmakers NJ. Prevalence of burnout in healthcare professionals providing palliative care and the effect of interventions to reduce symptoms: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med. 2021;35(1):6–26.

Teo YH, Peh TY, Abdurrahman A, Lee A, Chiam M, Fong W et al. A modified delphi approach to enhance nurturing of professionalism in postgraduate medical education in Singapore. Singap Med J. 2021.

Hee JM, Yap HW, Ong ZX, Quek SQM, Toh YP, Mason S, et al. Understanding the mentoring environment through thematic analysis of the learning environment in medical education: a systematic review. JJ Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(10):2190–9.

Lim SYS, Koh EYH, Tan BJX, Toh YP, Mason S, Krishna LKR. Enhancing geriatric oncology training through a combination of novice mentoring and peer and near-peer mentoring: a thematic analysis ofmentoring in medicine between 2000 and 2017. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(4):566–75.

Kilbertus F, Ajjawi R, Archibald DB. You’re not trying to save somebody from death: learning as becoming in palliative care. Acad Med. 2018;93(6):929–36.

Burford B. Group processes in medical education: learning from social identity theory. Med Educ. 2012;46(2):143–52.

Sawatsky AP, Nordhues HC, Merry SP, Bashir MU, Hafferty FW. Transformative learning and professional identity formation during international health electives: a qualitative study using grounded theory. Acad Med. 2018;93(9):1381–90.

Soo J, Brett-MacLean P, Cave M-T, Oswald A. At the precipice: a prospective exploration of medical students’ expectations of the pre-clerkship to clerkship transition. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2016;21(1):141–62.

Hamstra SJ, Woodrow SI, Mangrulkar RS. Feeling pressure to stay late: Socialisation and professional identity formation in graduate medical education. Med Educ. 2008;42(1):7–9.

Wilson I, Cowin LS, Johnson M, Young H. Professional identity in medical students: pedagogical challenges to medical education. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(4):369–73.

Wald HS, White J, Reis SP, Esquibel AY, Anthony D. Grappling with complexity: medical students’ reflective writings about challenging patient encounters as a window into professional identity formation. Med Teach. 2019;41(2):152–60.

Matthews R, Smith-Han K, Nicholson H. From physiotherapy to the army: negotiating previously developed professional identities in mature medical students. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2020;25(3):607–27.

Stuart E, O’Leary D, Rowntree R, Carey C, O’Rourke L, O’Brien E, et al. Challenges in experiential learning during transition to clinical practice: a comparative analysis of reflective writing assignments during general practice, paediatrics and psychiatry clerkships. Med Teach. 2020;42(11):1275–82.

Rosenthal S, Howard B, Schlussel YR, Herrigel D, Smolarz BG, Gable B, et al. Humanism at heart: preserving empathy in third-year medical students. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):350–8.

Wright SM, Levine RB, Beasley B, Haidet P, Gress TW, Caccamese S, et al. Personal growth and its correlates during residency training. Med Educ. 2006;40(8):737–45.

Levine RB, Haidet P, Kern DE, Beasley BW, Bensinger L, Brady DW, et al. Personal growth during internship. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):564–9.

Fischer MA, Haley H-L, Saarinen CL, Chretien KC. Comparison of blogged and written reflections in two medicine clerkships. Med Educ. 2011;45(2):166–75.

Kern DE, Wright SM, Carrese JA, Lipkin M Jr., Simmons JM, Novack DH, et al. Personal growth in medical faculty: a qualitative study. West J Med. 2001;175(2):92–8.

Kimmons R, Veletsianos G. The fragmented educator 2.0: Social networking sites, acceptable identity fragments, and the identity constellation. Comput Educ. 2014;72:292–301.

Gosselink MJ. Medical weblogs: advocacy for positive cyber role models. Clin Teach. 2011;8(4):245–8.

Fieseler C, Meckel M, Ranzini G. Professional personae - how organizational identification shapes online identity in the workplace. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2014;20(2):153–70.

Stokes J, Price B. Social media, visual culture and contemporary identity. Open Cybern Syst J. 2017:159–63.

Maghrabi RO, Oakley RL, Nemati HR. The impact of self-selected identity on productive or perverse social capital in social network sites. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;33:367–71.

Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, Brainard G, Herrine SK, Isenberg GA, et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med. 2009;84(9):1182–91.

Newton BW, Barber L, Clardy J, Cleveland E, O’Sullivan P. Is there hardening of the heart during medical school? Acad Med. 2008;83(3):244–9.

Kaczmarczyk JM, Chuang A, Dugoff L, Abbott JF, Cullimore AJ, Dalrymple J, et al. E-professionalism: a new frontier in medical education. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(2):165–70.

Brown J, Reid H, Dornan T, Nestel D. Becoming a clinician: Trainee identity formation within the general practice supervisory relationship. Med Educ. 2020;54(11):993–1005.

Henschen BL, Bierman JA, Wayne DB, Ryan ER, Thomas JX, Curry RH, et al. Four-year educational and patient care outcomes of a team-based primary care longitudinal clerkship. Acad Med. 2015;90(11 Suppl):S43–49.

Lim-Dunham JE, Ensminger DC, McNulty JA, Hoyt AE, Chandrasekhar AJ. A vertically integrated online radiology curriculum developed as a cognitive apprenticeship: impact on student performance and learning. Acad Radiol. 2016;23(2):252–61.

Sen Gupta TK, Muray RB, McDonell A, Murphy B, Underhill AD. Rural internships for final year students: clinical experience, education and workforce. Rural Remote Health. 2008;8(1):827.

Yardley S, Teunissen PW, Dornan T. Experiential learning: AMEE guide 63. Med Teach. 2012;34(2):e102–115.

Dickinson BL, Gibson K, VanDerKolk K, Greene J, Rosu CA, Navedo DD et al. It is this very knowledge that makes us doctors: An applied thematic analysis of how medical students perceive the relevance of biomedical science knowledge to clinical medicine. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):Article 356.

Sarraf-Yazdi S, Teo YN, How AEH, Teo YH, Goh S, Kow CS, et al. A scoping review of professional identity formation in undergraduate medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(11):3511–21.

Alford CL, Currie DM. Introducing first-year medical students to clinical practice by having them shadow third-year clerks. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16(3):260–3.

Boudreau JD, Macdonald ME, Steinert Y. Affirming professional identities through an apprenticeship: insights from a four-year longitudinal case study. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):1038–45.

Peer KS. Professional identity formation: considerations for athletic training education. Athl Train Educ J. 2016;11(3):125–6.

Klamen DL, Williams R, Hingle S. Getting real: aligning the learning needs of clerkship students with the current clinical environment. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):53–8.

Régo P, Peterson R, Callaway L, Ward M, O’Brien C, Donald K. Using a structured clinical coaching program to improve clinical skills training and assessment, as well as teachers’ and students’ satisfaction. Med Teach. 2009;31(12):e586–595.

Gheasuddin AN, Misra R, Patel J. Use of an apprenticeship model to facilitate prescribing learning on clinical placements. Med Teach. 2022;44(8):940.

Bettin KA. The role of mentoring in the professional identity formation of medical students. Orthop Clin North Am. 2020;52(1).

Baerheim A, Thesen J. Medical students’ evaluation of preceptorship in general practice in Vestlandet. Tidsskr nor Laegeforen. 2003;123(16):2271–3.

Golden BP, Henschen BL, Gard LA, Ryan ER, Evans DB, Bierman J, et al. Learning to be a doctor: medical students’ perception of their roles in longitudinal outpatient clerkships. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(11):2018–24.

Harris GD, Professionalism. Part ii - teaching and assessing the learner’s professionalism. Fam Med. 2004;36(6):390–2.

Sheu L, Goglin S, Collins S, Cornett P, Clemons S, O’Sullivan PS. How do clinical electives during the clerkship year influence career exploration? A qualitative study. Teach Learn Med. 2021:1–11.

Hay A, Smithson S, Mann K, Dornan T. Medical students’ reactions to an experience-based learning model of clinical education. Perspect Med Educ. 2013;2(2):58–71.

Abbey L, Willett R, Selby-Penczak R, McKnight R. Social learning: medical student perceptions of geriatric house calls. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2010;31(2):149–62.

Côté L, Laughrea PA. Preceptors’ understanding and use of role modeling to develop the canmeds competencies in residents. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):934–9.

Goldstein EA, MacLaren CF, Smith S, Mengert TJ, Maestas RR, Foy HM, et al. Promoting fundamental clinical skills: a competency-based college approach at the University of Washington. Acad Med. 2005;80(5):423–33.

Jones K, Reis S. Learning through vulnerability: a mentor-mentee experience. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(6):552–5.

Kalén S, Stenfors-Hayes T, Hylin U, Larm MF, Hindbeck H, Ponzer S. Mentoring medical students during clinical courses: a way to enhance professional development. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):e315–321.

Tariq M, Iqbal S, Haider SI, Abbas A. Using the cognitive apprenticeship model to identify learning strategies that learners view as effective in ward rounds. Postgrad Med J. 2021;97(1143):5–9.

Braniff C, Spence RA, Stevenson M, Boohan M, Watson P. Assistantship improves medical students’ perception of their preparedness for starting work. Med Teach. 2016;38(1):51–8.

Iwata K, Gill D. Learning through work: clinical shadowing of junior doctors by first year medical students. Med Teach. 2013;35(8):633–8.

Bleakley A. Pre-registration house officers and ward-based learning: a ‘new apprenticeship’ model. Med Educ. 2002;36(1):9–15.

Brody DS, Ryan K, Kuzma MA, Suppl. S105–109.

Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. Springer Publishing Company; 2006.

Ng YX, Koh ZYK, Yap HW, Tay KT, Tan XH, Ong YT, et al. Assessing mentoring: a scoping review of mentoring assessment tools in internal medicine between 1990 and 2019. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5):e0232511.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):72–8.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;59(1).

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. Rameses publication standards: Meta-narrative reviews. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):Article20.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Ong YT, Quek CWN, Pisupati A, Loh EKY, Venktaramana V, Chiam M, et al. Mentoring future mentors in undergraduate medical education. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(9):e0273358–0273358.

Venktaramana V, Ong YT, Yeo JW, Pisupati A, Krishna LKR. Understanding mentoring relationships between mentees, peer and senior mentors. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):76.

Chan JSK, Lau D, King E, Roever L, Liu T, Shum Y, et al. Virtual medical research mentoring. Clin Teach. 2023;20(4):e13598.

Joe MB, Cusano A, Leckie J, Czuczman N, Exner K, Yong H, et al. Mentorship programs in residency: a scoping review. J Grad Med Educ. 2023;15(2):190–200.

Lupi A, Shu L, Lopez A. Local mentoring as a strategy to recruit a more diverse physician workforce. Acad Med. 2022;97(6):779–80.

Krishna LKR, Pisupati A, Ong YT, Teo KJH, Teo MYK, Venktaramana V, et al. Assessing the effects of a mentoring program on professional identity formation. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):Article799.

Krishna LKR, Pisupati A, Teo KJH, Teo MYK, Quek CWN, Chua KZY, et al. Professional identity formation amongst peer-mentors in a research-based mentoring programme. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):Article787.

Munoz JA, Sarmiento MA, Alejandra Esparza Y, Shipp A, Luisa Veloz A, Edith Esparza Y, et al. Mentoring medical students: voices from Zoom rooms during the pandemic. Int J Divers Educ. 2022;23(1):25–34.

Drossard S, Härtl A. Development and implementation of digital peer mentoring in small groups for first-year medical students. GMS J Med Educ. 2024;41(1):Doc11.

Scholz A, Gehres V, Schrimpf A, Bleckwenn M, Deutsch T, Geier AK. Long-term mentoring relationships in undergraduate longitudinal general practice tracks - a qualitative study on the perspective of students and general practitioners. Med Educ Online. 2023;28(1):2149252.

Shen MR, Tzioumis E, Andersen E, Wouk K, McCall R, Li W, et al. Impact of mentoring on academic career success for women in medicine: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2022;97(3):444–58.

Hartlage CS, Sosa DM. Everyone deserves a seat at the table: mentoring to uplift minoritized trainees. Acad Med. 2023.

Lee SI, Bluemke DA. Mentoring in academic radiology. Radiology. 2022;303(1):E20–2.

Sharma A, Leeper H, Bang S, Molaie D, Porter AB. The impact of mentoring on early career faculty: Assessment of a virtual mentoring program. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16).

Murphy M, Record H, Callander JK, Dohan D, Grandis JR. Mentoring relationships and gender inequities in academic medicine: findings from a multi-institutional qualitative study. Acad Med. 2022;97(1):136–42.

Farrukh K, Hoor T. Online mentoring session during COVID-19: experiences of mentees and mentors - a phenomenology. Prof Med J. 2022;29(12):1886–91.

Bui DT, Barnett T, Hoang H, Chinthammit W. Development of a framework to support situational tele-mentorship of rural and remote practice. Med Teach. 2023;45(6):642–9.

Ramani S, Chugh N, Chisolm MS, Hays R, McKimm J, Kusurkar R, et al. Mentoring relationships: a mentee’s journey. Acad Med. 2023;98(3):423.

Williams JS, Walker RJ, Burgess KM, Shay LA, Schmidt S, Tsevat J, et al. Mentoring strategies to support diversity in research-focused junior faculty: a scoping review. J Clin Transl Sci. 2023;7(1):e21.

Koven S. What is a mentor? N Engl J Med. 2024;390(8):683–5.

Jafari M, Moodi Ghalibaf A. Peer-research learning and mentoring for undergraduate medical students: benefits and challenges. Res Dev Med Educ. 2022;11:19.

Kalet A, Libby AM, Jagsi R, Brady K, Chavis-Keeling D, Pillinger MH, et al. Mentoring underrepresented minority physician-scientists to success. Acad Med. 2022;97(4):497–502.

Koh EYH, Koh KK, Renganathan Y, Krishna L. Role modelling in professional identity formation: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):194.

Stadtlander L, Ozcan A, Johnson L, Nicholson B, Hyder N. Faculty and student online mentoring preferences. J Educ Res Pract. 2022;12(1).

Heffernan L, O’Dowd E. Em and me: near-peer mentoring in an emergency department. Ir Med J. 2023;116(10):874–83.

Behkam S, Tavallaei A, Maghbouli N, Mafinejad MK, Ali JH. Students’ perception of educational environment based on Dundee ready education environment measure and the role of peer mentoring: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):Article176.

Pfund C, Sancheznieto F, Byars-Winston A, Zárate S, Black S, Birren B et al. Evaluation of a culturally responsive mentorship education program for the advisers of howard hughes medical institute gilliam program graduate students. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2022;21(3):Article 50.

Hill SEM, Ward WL, Seay A, Buzenski J. The nature and evolution of the mentoring relationship in academic health centers. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2022;29(3):557–69.

Jan S, Mahboob U. Online mentoring: challenges and strategies. Pak J Med Sci. 2022;38(8):2272–7.

Krishna L, Toh YP, Mason S, Kanesvaran R. Mentoring stages: a study of undergraduate mentoring in palliative medicine in Singapore. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0214643.

Hee J, Toh YL, Yap HW, Toh YP, Kanesvaran R, Mason S, et al. The development and design of a framework to match mentees and mentors through a systematic review and thematic analysis of mentoring programs between 2000 and 2015. Mentor Tutoring: Partnersh Learn. 2020;28(3):340–64.

Schrempf S, Herrigel L, Pohlmann J, Griewatz J, Lammerding-Köppel M. Everybody is able to reflect, or aren’t they? Evaluating the development of medical professionalism via a longitudinal portfolio mentoring program from a student perspective. GMS J Med Educ. 2022;39(1):Doc12.

Junn JC, Whitman GJ, Wasnik AP, Wang MX, Guelfguat M, Goodman ED, et al. Virtual mentoring: a guide to navigating a new age in mentorship. Acad Radiol. 2023;30(4):749–54.

Lakhani DA, Swaney KJ, Hogg JP. Resident managed peer-mentoring program: a novel way to engage medical students and radiology residents in collaborative research. Acad Radiol. 2022;29(9):1425–31.

Dancer JM. Mentoring in healthcare: theory in search of practice? Clin Manag. 2003;12(1):21–31.

Welsh ET, Bhave D, yong Kim K. Are you my mentor? Informal mentoring mutual identification. Career Dev Int. 2012;17(2):137–48.

Reiss TF, Moss J, Watkins TR, Malhotra A. BEAR cage: mentoring through engagement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(7):714–6.

Sonawane T, Meshram R, Jagia G, Gajbhiye R, Adhikari S. Effects of mentoring in first year medical undergraduate students using DASS-21. J Clin Diagn Res. 2021;15(11):7–10.

Stamm M, Buddeberg-Fischer B. The impact of mentoring during postgraduate training on doctors’ career success. Med Educ. 2011;45(5):488–96.

Yehia BR, Cronholm PF, Wilson N, Palmer SC, Sisson SD, Guilliames CE et al. Mentorship and pursuit of academic medicine careers: A mixed methods study of residents from diverse backgrounds. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):Article 26.

Eby LT, Butts MM, Durley J, Ragins BR. Are bad experiences stronger than good ones in mentoring relationships? Evidence from the protégé and mentor perspective. J Vocat Behav. 2010;77(1):81–92.

Mohd Shafiaai MSF, Kadirvelu A, Pamidi N. Peer mentoring experience on becoming a good doctor: student perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):Article494.

Morrison LJ, Lorens E, Bandiera G, Liles WC, Lee L, Hyland R, et al. Impact of a formal mentoring program on academic promotion of department of medicine faculty: a comparative study. Med Teach. 2014;36(7):608–14.

Ng CH, Ong ZH, Koh JWH, Ang RZE, Tan LHS, Tay KT, et al. Enhancing interprofessional communications training in internal medicine. Lessons drawn from a systematic scoping review from 2000 to 2018. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2020;40(1):27–35.

Pinilla S, Pander T, von der Borch P, Fischer MR, Dimitriadis K. 5 years of experience with a large-scale mentoring program for medical students. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2015;32(1):Doc5.

Sng JH, Pei Y, Toh YP, Peh TY, Neo SH, Krishna LKR. Mentoring relationships between senior physicians and junior doctors and/or medical students: a thematic review. Med Teach. 2017;39(8):866–75.

Farid H, Bain P, Huang G. A scoping review of peer mentoring in medicine. Clin Teach. 2022;19(5):e13512.

Li MK, Adus SL, Weyman K. There’s always something to talk about! The unexpected benefits of going virtual in a Canadian diversity mentorship program. Can Med Educ J. 2022;13(1):90–2.

Frizell CA, Caruthers KL, Sturges D. Intentional mentoring of healthcare provider students from underrepresented groups in medicine. Med Sci Educ. 2023;33(3):807–8.

Aziz A, Shadab W, Siddique L, Mahboob U. Exploring the experiences of struggling undergraduate medical students with formal mentoring program at a private medical college in Rawalpindi. Pak J Med Sci. 2023;39(3):815–9.

Penaloza NG, Ardines KEZ, Does S, Washington SL III, Tandel MD, Braddock CH III, et al. Someone like me: an examination of the importance of race-concordant mentorship in urology. Urology. 2023;171:41–8.

Silver JK. Six practical strategies to mentor and sponsor women in academic medicine. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e47799.

Verhoef L, Vivekanantham A, Berti A, Bolek E, Smeele H, Oztas M, et al. The emerging eular network (emeunet) peer-review mentoring program: ten years of initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:202–3.

Chia EWY, Tay KT, Xiao S, Teo YH, Ong YT, Chiam M, et al. The pivotal role of host organizations in enhancing mentoring in internal medicine: a scoping review. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520956647.

Cameron KA, Rodrigues TJ, Keswani RN. Developing a mentoring network to navigate fellowship and beyond: moving from mentor to mentors. Gastroenterology. 2024;166(5):723–e727721.

Silver JK, Gavini N. The push-pull mentoring model: ensuring the success of mentors and mentees. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e48037.

Kuzman M. Academic mentoring for psychiatric trainees during the pandemic. Eur Psychiatry. 2022;65:S60.

Tetzlaff J, Lomberk G, Smith HM, Agrawal H, Siegel DH, Apps JN. Adapting mentoring in times of crisis: what we learned from COVID-19. Acad Psychiatry. 2022;46(6):774–9.

Barron B. Interest and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: a learning ecology perspective. Hum Dev. 2006;49(4):193–224.

Karcher MJ, Kuperminc GP, Portwood SG, Sipe CL, Taylor AS. Mentoring programs: a framework to inform program development, research, and evaluation. J Community Psychol. 2006;34(6):709–25.

Wells JN, Cagle CS. Preparation and participation of undergraduate students to inform culturally sensitive research. Nurse Educ Today. 2009;29(5):505–9.

Bozeman B, Feeney MK. Toward a useful theory of mentoring: a conceptual analysis and critique. Admin Soc. 2007;39(6):719–39.

Indyk D, Deen D, Fornari A, Santos MT, Lu W-H, Rucker L. The influence of longitudinal mentoring on medical student selection of primary care residencies. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1):Article27.

Meeuwissen SN, Stalmeijer RE, Govaerts M. Multiple-role mentoring: mentors’ conceptualisations, enactments and role conflicts. Med Educ. 2019;53(6):605–15.

Rangachari D, Brown LE, Kern DE, Melia MT. Clinical coaching: evolving the apprenticeship model for modern housestaff. Med Teach. 2017;39(7):780–2.

Pront L, Gillham D, Schuwirth LW. Competencies to enable learning-focused clinical supervision: a thematic analysis of the literature. Med Educ. 2016;50(4):485–95.

Yang MM, Golden BP, Cameron KA, Gard L, Bierman JA, Evans DB, et al. Learning through teaching: peer teaching and mentoring experiences among third-year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2022;34(4):360–7.

Lynn L, Stadtlander L, Inman D, Burkholder G, Morgan A. Transforming doctoral mentoring expectations and culture: an action model approach. New Dir Teach Learn. 2023;2023(176):75–82.

Moore JL, Myers A, McConnell H. Mentoring high-impact undergraduate research experiences. Pedagogy. 2022;22(1):17–21.

Mishra MK. Evidence-based learning modules and culturally responsive mentoring to engage underserved undergraduate students. J Immunol. 2022;208(1Supplement):106116.

Moawad H. Best practices for mentoring new physicians. Oncology. 2022 2022/02//:127.

Hoffmeyer C, Milliren A, Eckstein D. The Hoffmeyer mentoring activity checklist: invitations to professional growth. J Invitational Theory Pract. 2022;11:54–62.

Palmeri M, Bono K, Huang A, Gunther JR, Mattes MD. Characterization of research mentorship during medical school for future radiation oncology trainees. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2024;9(5):101460.

De Rosa S, Battaglini D, Bennett V, Rodriguez-Ruiz E, Zaher AMS, Galarza L, et al. Key steps and suggestions for a promising approach to a critical care mentoring program. J Anesth Analg Crit Care. 2023;3(1):30.

Jacob RA, Williams PN, Chisty A. Twelve tips for developing and maintaining a successful peer mentoring program for junior faculty in academic medicine. Med Teach. 2022;45(3):252–6.

Templeton NR, Jeong S, Villarreal E. Editorial overview: mentoring to support professional knowledge. Mentor Tutoring: Partnersh Learn. 2022;30(3):275–9.

Rallis KS, Wozniak A, Hui S, Stammer A, Cinar C, Sun M, et al. Mentoring medical students towards oncology: results from a pilot multi-institutional mentorship programme. J Cancer Educ. 2022;37(4):1053–65.

Kusner JJ, Chen JJ, Saldaña F, Potter J. Aligning student-faculty mentorship expectations and needs to promote professional identity formation in undergraduate medical education. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2022;9:23821205221096307.

Khatun M, Akter P, Yunus S, Alam K, Pedersen C, Byrskog U, et al. Challenges to implement evidence-based midwifery care in Bangladesh. An interview study with medical doctors mentoring health care providers. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2022;31:100692.

Torre DM, Daley BJ, Sebastian JL, Elnicki DM. Overview of current learning theories for medical educators. Am J Med. 2006;119(10):903–7.

Gormley B. An application of attachment theory: mentoring relationship dynamics and ethical concerns. Mentor Tutoring: Partnersh Learn. 2008;16(1):45–62.

Taylor DC, Hamdy H. Adult learning theories: implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE guide 83. Med Teach. 2013;35(11):e1561–72.

Lewis C, Olshansky E. Relational-cultural theory as a framework for mentoring in academia: toward diversity and growth-fostering collaborative scholarly relationships. Mentor Tutoring: Partnersh Learn. 2016;24(5):383–98.

Heeneman S, de Grave W. Tensions in mentoring medical students toward self-directed and reflective learning in a longitudinal portfolio-based mentoring system–an activity theory analysis. Med Teach. 2017;39(4):368–76.

Irby BJ, Boswell JN, Searby LJ, Kochan F, Garza R, Abdelrahman N. The Wiley international handbook of mentoring: Wiley; 2020.

Wadi MM, Yusoff MSB, Taha MH, Shorbagi S, Nik Lah NAZ, Abdul Rahim AF. The framework of systematic Assessment for Resilience (SAR): development and validation. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1): Article 213.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Annelissa Chew Chin for her expert guidance and advice in designing our search strategy. The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the late Dr. S Radha Krishna and A/Prof Cynthia Goh whose advice and ideas were integral to the success of this review and Thondy, Maia Olivia and Raja Kamarul whose lives continue to inspire us.The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments which greatly enhanced this manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors MYKT, HI, CKLR, NABAH, RG, NS, CL, JLG, YZ, KTT, RRSO, VT, TY, AP, VR, KZYC, ELYQ, JS, SDS, KS, WTWL, RSMW, YP, JHS, SQMQ, JLJO, TTY, EKO, GLGP, SM, RH, ARC, SYKO, and LKRK were involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, preparing the original draft of the manuscript as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions