Abstract

Background

The assessment of pharmacy students’ readiness to begin the education of an advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) in clinical pharmacy settings continues to gain increasing attention. This study aimed to develop an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) in the core domains acquired through an introductory pharmacy practice experience (IPPE), for evaluating its appropriateness as a tool of assessing clinical pharmacist competency for APPEs in Korean pharmacy students throughout a pilot study.

Methods

OSCE’s core competency domains and case scenarios were developed through a literature review, ideation by researchers, and external experts’ consensus by a Delphi method. A prospective single-arm pilot test was conducted to implement the OSCE for Korean pharmacy students who completed a 60-h course of in-class simulation IPPE. Their competencies were assessed by four assessors in each OSCE station with a pass-fail grading system accompanied by a scoring rubric.

Results

OSCE competency areas including patient counseling, provision of drug information, over-the-counter (OTC) counseling, and pharmaceutical care services were developed with four interactive and one non-interactive cases. Twenty pharmacy students participated in the OSCE pilot test, and their competencies were evaluated by 20 assessors. The performance rate was the lowest in the area of patient counseling for a respiratory inhaler (32.1%) and the highest (79.7%) in OTC counseling for constipation. The students had an average performance rate of 60.4% in their communication skills. Most participants agreed on the appropriateness, necessity, and effectiveness of the OSCE in evaluating pharmacy students’ clinical performance and communication skills.

Conclusions

The OSCE model can be used to assess pharmacy students’ readiness for off-campus clinical pharmacy practice experience. Our pilot study suggests the necessity of conducting an OSCE domain-based adjustment of difficulty levels, and strengthening simulation-based IPPE education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The pharmacy educational system in South Korea was reformed to a six-year (2 + 4) program in 2009. The major change comprised introducing pharmacy practice experiences to cultivate students’ competencies by enabling them to acquire knowledge, skills, and attitude to perform a pharmacist’s role in various practical fields [1]. The experiential education program consists of two phases: the introductory pharmacy practice experience (IPPE) courses for 60 h, where students are exposed to simulated pharmacy practice environments within the college of pharmacy, and the advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) courses of training in hospital and community pharmacy track, industrial/administrative pharmacy track, or pharmacy research track for 1340 h [2, 3].

The assessment of pharmacy students’ readiness to begin APPE education in clinical pharmacy settings continues to gain increasing attention [4, 5]. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) in the United States (US) has emphasized the importance of competency assessment with comprehensive, formative, and summative testing [6, 7]. Since pharmacy practice training was first implemented eighth years ago in South Korea, preceptors and students have raised concerns related to experiential education, such as differences in IPPE educational content and quality among 37 colleges of pharmacy and differences in students’ competence in translating knowledge levels into practice [8, 9]. Despite the apparent need for a competency assessment program to assess students’ readiness for experiential learning, there are no established standardized examinations or evaluation criteria to assess students’ clinical performance consistently and accurately.

Objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) was first introduced as a novel method of assessing the clinical competence of medical students and has been adapted to numerous other health professional programs, including doctor of pharmacy curricula. The OSCE is advantageous in evaluating competency in difficult-to-assess areas, such as communication, problem solving, and decision-making, with relatively high reliability, validity, and objectivity [10, 11]. In the US and Canada, the OSCE has been implemented in doctor of pharmacy programs or national pharmacist licensure examinations to evaluate whether pharmacy students have the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes for clinical practice [12, 13]. Standardized OSCE models have been developed in countries including the US, the United Kingdom (UK), Canada, Japan, Malaysia, and the Middle East, for examining the progress in assessing students’ readiness for clinical practice [5, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. However, there is no generalized assessment program to determine the performance readiness of pharmacy students prior to beginning APPEs. The OSCEs have been developed in the US for assessing competencies acquired during an IPPE [5, 15]. Nevertheless, it is difficult to apply it for the outcome assessment of education only with in-class simulation system, since the IPPEs in the US includes the off-campus training [2, 6, 7]. This study aimed to develop an OSCE in the core domains acquired through an IPPE, to evaluate its appropriateness as a tool for assessing clinical pharmacist competency for APPEs in Korean pharmacy students, throughout a pilot study.

Methods

OSCE development

To establish the OSCE blueprint, we set its core values as human dignity, professionalism, and social responsibility (Fig. 1) [6,7,8]. The OSCE’s core competency domains demonstrated by pharmacy students who completed the IPPE courses, were selected through review of literature related to OSCEs for pharmacy students and pharmacists’ practice examination in the US, the UK, Canada, and Japan [3,4,5,6,7,8, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24], ideation by researchers, and group discussions with experts. We primarily referenced duties for clinical performance test, suggested by Han et al., and the Korean official textbook of IPPE [22, 25].

To develop OSCE cases related to each OSCE competency domain, we identified case objectives and explored possible case scenarios related to each OSCE topic based on the textbooks of IPPE and pharmacotherapy used in 37 colleges of pharmacy in Korea [25, 26] and ideation by the researchers. Subsequently, we finalized the simulated case scenarios and assessment criteria for the clinical performance and communication skills of the students within the given time constraints (i.e., 10 min for each case) through review by external experts qualified for the education of clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice. They reviewed the OSCE cases and competency criteria to achieve a consensus by the Delphi method [27]. The case scenarios consisted of the title, interactive/non-interactive, purpose of the OSCE, time, materials, instructions for students and questions, instructions for standardized patients/physicians, and instructions for assessors (i.e., answer and assessment criteria). The instructions for standardized patients/physicians contained a specific script with an information guide on the reactions of standardized actors to students’ responses. Development of an assessment criteria along with a scoring rubric, helped evaluate clinical performance skills of pharmacy students, such as critical thinking, patient-centered problem solving, overall attitude and behavior, and provision of correct information, as well as their communication skills, according to each OSCE topic [6,7,8, 25, 28].

Setting and subjects

A pilot study was designed as a prospective single-arm observational trial to evaluate the clinical competency of pharmacy students in South Korea prior to APPEs by implementing the OSCE models developed in this study. The inclusion criterion for participants was third-year students of pharmacy schools (i.e., fifth-grade at South Korean pharmacy colleges), who had completed 60 h of IPPE. They were recruited via flyers posted on the website of the Korean Association of Pharmacy Education and four colleges of pharmacy located in Daegu and Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea. Assessors who were preceptors of APPEs or clinical faculty members at pharmacy colleges with at least two years of IPPE or APPE educational experience were asked to participate in the study by the researchers to assess the clinical pharmacist competency of the students. On the day for the pilot test, all students or assessors attended their own respective briefing session. They were informed about the OSCE procedure, the total expected time for the exam or assessment, number of simulated cases, and stations with standardized patients/physicians, as well as the survey after the OSCE’s completion. The competency evaluation criteria and rubric scoring methods were explained to the assessors. All participants submitted a written spontaneous participation consent before enrolling in the study.

This pilot study was conducted at Keimyung University’s College of Pharmacy in South Korea, on September 26, 2020. Each core domain of the OSCE was examined at five stations, using a mock pharmacy and standardized patients/physicians with simulated tasks or problems. Prior to the day of the OSCE, four actors serving as patients or physicians received a 30-min training from the primary investigators, along with scripts for the simulation. On the day for the pilot test, students were randomly assigned to four groups of five, and took the exam at five stations for each OSCE case. Each case required 10 min, that is, two minutes of preparation time in front of the station, seven minutes of test time, and one minute of travel time to the next station. A research assistant in each station managed the time schedule, and two coordinators facilitated the overall OSCE process. A small amount of allowance for research participation was paid to all participants (i.e., students or assessors), standardized patients/physicians, coordinators, and assistants.

Assessors and scoring

The assessors were provided with competency assessment mark sheets with a binary grading system (i.e., pass or fail) developed according to each OSCE case in this study. Four assessors assigned to each station based on the peer investigator's judgement, evaluated the competencies of all students as per the provided criteria. The pass-fail grading system is appropriate to assess the clinical simulation performance of the healthcare students [29, 30]. The assessors were provided with specific exemplar answers for each evaluation criterion to make their assessment similar. For each evaluation criterion, the students received either a pass or a fail on their clinical performance or communication skills, from the assessors with the following standards: (1) a pass when meeting 50% or more of each assessment criterion for clinical performance and communication skills and (2) a fail when meeting less than 50% of each assessment criterion. Consequently, the students and assessors conducted surveys with a four-point Likert scale on the difficulty, usefulness, and satisfaction of each OSCE competency area. Students were informed that they could individually attain their assessment results if desired.

Analysis

Data are shown as numbers and percentages for categorical variables, and as means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous data. The difficulty of the OSCEs was evaluated based on the students’ performance rates which were measured by the percentage of students who passed each assessment criterion. The OSCE was considered difficult if the performance rate was less than 40% and easy if the rate was greater than 80% [31, 32]. Fisher’s exact and chi-square tests were used to compare the clinical performance assessment results between professors and hospital/community pharmacists as well as survey results between students and assessors. Statistical significance was set at a two-sided p-value of < 0.05, and data analysis and computation were conducted using SPSS Statistics (version 22.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Development of OSCE’s core competency domains and cases

We finally determined five core competency domains for the assessment of pharmacy students’ readiness for the APPEs, which were: (1) patient counseling; (2) prescription review; (3) provision of drug information; (4) over-the-counter (OTC) counseling; and (5) pharmaceutical care service. The prescription review area was selected instead of the drug preparation and dispensing areas suggested by Han et al. [22], since researchers determined that the competencies related to dispensing should be evaluated after the APPEs [25]. The detailed topics and general assessment criteria related to each OSCE’s core competency domain are listed in Table 1. Of the five competency domains, four were interactive examinations involving standardized patients/physicians, and only the prescription review area was a non-interactive one, where the student had to solve problems and present them to the assessors. Summaries of the simulated case scenarios for the five competency areas are presented in Table 2. For example, the objectives of the patient counseling case were to counsel and educate a patient with asthma on a dry-powder inhaler. This station simulated a 25-year-old man who came to the pharmacy with a prescription for a fluticasone inhaler, and the student was asked to provide appropriate patient education and counseling. A four-level rubric was set to score students’ competency in the OSCE, including (1) outstanding for the achievement of 90% or more, (2) clear pass for 70 − 89%, (3) borderline pass for 50 − 69%, and (4) clear failure for less than 50%.

Implementation of the OSCE in a pilot test

Twenty students from two pharmacy colleges located in Daegu and Gyeongsangbuk-do were included. As shown in Table 3, there were also 20 evaluators from community and hospital pharmacies and colleges of pharmacy with at least two years of educational experience, either in the IPPEs or APPEs.

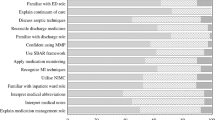

Table 4 demonstrated that the overall performance rate of the students was 50.8%. The average performance rates were 32.1, 64.8, 65.4, 79.7, and 62.5% in patient counseling, prescription review, provision of drug information, OTC counseling, and pharmaceutical care service, respectively. Among the 18 assessment criteria in patient counseling, the students had a performance rate of less than 40% for the 11 criteria, and no one met the following two criteria: “Explain expected length of the patient counseling session” and “Allow patients to summarize and organize relevant education and counseling.” Among the 14 criteria in the prescription review area, the students’ performance was less than 40% for the following three criteria: “Note that the physician’s signature on the prescription is missing”; “Note that the prescription expiration date is missing”; and “Check the patient’s age.” In drug information provision, students’ performance was relatively low only for two of the six assessment criteria: “Reconfirm the question clearly” and “Provide proper information on naproxen co-administration.” The students’ performance was more than 50% for all four criteria in the OTC counseling. In pharmaceutical care service, students’ performance was low only for the assessment criterion, “The converted daily dose of oral prednisolone was designed using the appropriate number of tablets and frequency, considering the formulation and dose of those on the market.” among the total four criteria. The evaluation results of professors and hospital/community pharmacists differed statistically significantly in five of the six criteria in the drug information area, while only two of the 14 criteria were different in the prescription review area.

As shown in Table 5, the average performance rate in the seven assessment criteria for the students’ communication skills was 60.4%. However, only three criteria were passed by more than 80% of the students: “Use terms and expressions while considering the partner’s capacity for understanding.”; “Adhere to appropriate speech and an attitude that makes the partner (patient or healthcare professional) feel comfortable.”; and “Explain or respond with respect to the partner (patient or healthcare professional).”.

Table 6 shows the results of the students’ and assessors’ surveys after the OSCE was implemented. The students and assessors thought that the time for each session of the OSCE was sufficient, the questions were appropriate for evaluating the clinical performance of the students prior to the APPEs, and standardized OSCEs were necessary for the evaluation of students’ clinical pharmacist competencies acquired in the IPPEs. In addition, all of them agreed that students’ clinical performance would improve if OSCEs were conducted in the future. However, statistically, more students than assessors answered that the examinations for prescription review and OTC counseling were more difficult.

Discussion

As there is a need to improve healthcare services in Korea, pharmacy colleges have tried to develop methods to evaluate students’ practical skills and performance [8, 22]. This pilot study showed that application of the OSCE to Korean students completed in-class pharmacy simulation courses was feasible to assess their competencies and preparedness for the advanced training in community or hospital pharmacies. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to apply a standardized OSCE system to pharmacy students who completed 60-h IPPE courses at Korean colleges of pharmacy, in order to evaluate their clinical performance for the APPE curriculum comprehensively and objectively.

This OSCE model can evaluate nine of the 11 pre-APPE core domain competencies of the ACPE: patient safety; basic patient assessment; medication information; identification and assessment of drug related problems; mathematics applied to dose calculation; professional and legal behavior; general communication abilities; counseling patients; and drug information analysis and literature research [6, 7]. Unlike the Korean IPPE curriculum, the one in the US mainly includes off-campus practice in community and hospital pharmacies as along with in-class simulation training [6, 7]. The Pharmaceutical Common Achievement Tests Organization in Japan presented five OSCE competency areas, including patient counseling, dispensing, dispensing audit, aseptic dispensing, and provision of drug information [17]. The OSCE core domains in this study areas were developed after considering the IPPE curriculum and its official textbook, utilized by most Korean pharmacy schools [3, 25]. Counselling patients for complex dosage forms (i.e., respiratory inhalers or self-injection devices) or OTCs, has been a key competency for clinical pharmacists to provide effective health and medication information to patients, and confirm their understanding of it [6, 7, 25, 33]. By assessing students’ ability towards patient care and prescription review, we could evaluate their basic knowledge, critical thinking, and problem-solving competencies, for assessing patient conditions and DRPs in the community or hospital pharmacy. The competency of time bound drug information analysis and literature research, could be assessed by the area of drug information service, which required the use of adequate drug information resources and evidence-based pharmacotherapy, to provide safe and effective pharmacotherapy [6, 7, 15, 25, 26].

The OSCE stations with standardized patients or physicians were appropriate since pharmacy students have been recommended to complete a specific clinical task often in an interactive environment [21, 33, 34]. The students’ average performance was the lowest at 32.1% in the case of counseling the patient with the inhaler, and the highest at 79.7% in the OTC counseling. This might indicate towards the insufficient readiness of students, for counseling patients with prescribed inhalers at the community or hospital pharmacies. Contradictorily, the students found the cases related to prescription review and pharmaceutical care service, as well as patient counseling, difficult. In Korean pharmacy schools, the IPPE curriculum is operated as in-class simulation of prescription review, dispensing, medication therapy management, patient counseling, and drug information provision, while the APPE courses are conducted as field training at community or hospital pharmacies [2, 3]. Since participating students had not yet started APPE courses, the OSCE cases proved difficult, which resulted in their performance rate dropping below 80%, in certain criteria of all OSCE areas. Malaysian pharmacy students also considered the OSCE areas related to patient counseling, drug dosage review, and drug information service relatively difficult, compared to the areas related to drug-related problems or pharmacokinetics [19]. Despite pharmacists being required to counsel patients within the expected duration, and verify patients’ medication knowledge according to the pharmacist-conducted patient counseling guidelines and the textbook used in the Korean college of pharmacy, no student met the relevant assessment criteria [25, 34, 35]. This study also showed that students portrayed weaknesses at the beginning and end of the communication in clinical pharmacy practice. Contradictorily, Japanese students showed excellent outcomes in most communication skill areas, which was probably affected by the list of tasks provided a minute before the advanced OSCE [36]. The standardized IPPE curriculum applied to all colleges of pharmacy in South Korea is limited. It was reported that the incorporation of simulation based IPPE made pharmacy students more confident on technical and communication skills, and more aware of medication errors and other patient safety issues [15]. Therefore, Korean pharmacy colleges’ IPPE education should strengthen their curriculum based on simulation education, for applying the knowledge to actual clinical situations related to the five key competency areas, and involve the preceptors as reviewers to reduce the differences in the outcome assessment.

The pharmacy students, faculty, and preceptors, need to be introduced to the OSCE system. Implementation of OSCEs as part of the evaluation of clinical performance could help students improve their capabilities by identifying their current level via the assessment of their performances [14, 37]. In a study with third-year pharmacy students in the US, the OSCE was also found to be a means to evaluate students’ clinical capabilities obtained through IPPE practices [2, 5, 7]. Therefore, additional cases related to each OSCE core domain should be developed with the validated assessment criteria through continuous discussions between the pharmacy colleges’ faculty members and APPEs' preceptors. It is also necessary to standardize the OSCE content and lay the foundations for the OSCE introduction by referring to the OSCE system of other healthcare professionals to integrate the OSCE into the pharmacy curriculum. This might be ensured through the development of guidelines, which include details of the time of OSCE, eligibility, management of students, the execution of the exam (i.e., time, location, duration, etc.), assessment methods, and continuous quality management as well as the development and confidentiality of the OSCE cases/questions, by referring to this pilot study [21, 34]. However, the OSCE's adoption should consider an enormous budget allocation for space, administrative overhead, and faculty members’ time [13]. Further studies are needed to find a cost-effective way of introducing the OSCE in Korean pharmacy educational system.

Although several countries such as the US, Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom and Japan have used the OSCE in various ways for evaluating clinical competencies of pharmacy students, most pharmacy schools around the world have not yet introduced or are preparing to introduce the OSCE in their pharmaceutical education systems [21, 38]. Therefore, other countries or organizations could refer to the OSCE model developed in this study to develop or improve the OSCE system for competency assessment of students’ readiness for the pharmacy practice experiences in community or hospital pharmacies.

As this is the first study to implement an OSCE in Korea, some problems were encountered during the pilot test. First, only one case was developed for each core competency domain and implemented to a limited number of students in this pilot project, which could confound the OSCE’s assessment outcomes. Thus, it is desirable in the future to develop various simulated case scenarios and questions, and implement the OSCE on a larger number of students. Second, the scoring rubric and questionnaire used in this study lacked proper calibration or validation. Considering that the standardized scoring rubrics are essential for improving the assessment's consistency, further studies are needed to calibrate examiners on the use of rating scales before adopting the OSCE for Korean pharmacy students [28]. Finally, most of the pharmacy students hold insignificant information about the OSCE system, although we explained the overall OSCE procedure to the participants, in a briefing session before the pilot study. Therefore, some students might have difficulties in understanding the simulation based OSCE process and test questions. It was reported that the awareness of the simulated situation made students feel slightly unreal, where only 77% of the students speaking to the simulated patients felt like a real doctor [39]. Moreover, performance anxiety in certain students and examination unfamiliarity in both students and evaluators, probably caused relatively low performance rates in certain domains [40].

Conclusion

The OSCE for patient counseling, prescription review, drug information provision, OTC counseling, and pharmaceutical care services, can be used to assess those pharmacy students’ clinical competencies, who completed the 60-h IPPE course in a pharmacy college. Our pilot study suggests the necessity of an OSCE domain-based difficulty adjustment, and the strengthening of simulation-based IPPE education, through continuous discussion between the pharmacy faculties and preceptors for pharmacy students’ readiness to practice off-campus clinical pharmacy operations. Future studies are needed to validate this observation’s feasibility in large numbers of pharmacy students.

Availability of data and materials

The full contents of the OSCE cases and dataset generated and analyzed during the pilot study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACPE:

-

Accreditation council for pharmacy education

- APPE:

-

Advanced pharmacy practice experience

- BS:

-

Bachelor of science

- IPPE:

-

Introductory pharmacy practice experience

- MS:

-

Master of science

- NA:

-

Not available

- OSCE:

-

Objective structured clinical examination

- OTC:

-

Over-the-counter

- PhD:

-

Doctor of philosophy

- SD:

-

Standard deviations

- US:

-

The United States

References

Yoo S, Song S, Lee S, Kwon K, Kim E. Addressing the academic gap between 4- and 6-year pharmacy programs in South Korea. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(8):149.

Jung GY, Lee YJ. Examination of clinical pharmacy curriculum in Korea and its comparison to the U.S. curriculum. Korean J Clin Pharm. 2014;24(4):304–10.

Korean Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards for Korean Pharmacy Educational Program leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Korean Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. 2021. https://www.kacpe.or.kr/kr/news. Accessed 28 Dec 2021.

Mészáros K, Barnett MJ, McDonald K, Wehring H, Evans DJ, Sasaki-Hill D, et al. Progress examination for assessing students’ readiness for advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(6):109.

Martin RD, Ngo N, Silva H, Coyle WR. An objective structured clinical examination to assess competency acquired during an introductory pharmacy practice experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(4):7625.

Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Guidance for standards 2016. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. 2015. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/GuidanceForStandards2016FINAL2022.pdf. Accessed 30 May 2022.

Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the Professional Program in Pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Standards 2016. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. 2015. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL2022.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb 2022.

Yoon JH. Strategies for the improvement of pharmacy practice experiences education: focused on clinical pharmacy practice experiences. Korean Association of Pharmacy Education. 2018.

Chang MJ, Noh H, Lee JI. Construction and evaluation of the student practice program in the hospital under the 6-year college of pharmacy curriculum. Korean J Clin Pharm. 2013;23(4):300–6.

Harding D. The objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) explained. BMJ. 2017;358:j3618.

Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287(2):226–35.

The Pharmacy Examining Board of Canada. Pharmacist qualifying examination. https://pebc.ca/pharmacists/qualifying-examination/about-the-examination/. Accessed 22 Feb 2022.

Sturpe DA. Objective structured clinical examinations in doctor of pharmacy programs in the United States. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(8):148.

Ragan RE, Virtue DW, Chi SJ. An assessment program using standardized clients to determine student readiness for clinical practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(1):14.

Vyas D, Bhutada NS, Feng X. Patient simulation to demonstrate students’ competency in core domain abilities prior to beginning advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(9):176.

Kirton SB, Kravitz L. Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs) compared with traditional assessment methods. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(6):111.

Pharmaceutical Common Achievement Tests Organization. Objective structured clinical examination. https://www.phcat.or.jp. Accessed 27 Jan 2023.

The Pharmacy Examining Board of Canada (PEBC). Pharmacist Qualifying Examination. http://pebc.ca. Accessed 27 Jan 2023.

Awaisu A, Mohamed MH, Al-Efan QA. Perception of pharmacy students in Malaysia on the use of objective structured clinical examinations to evaluate competence. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(6):118.

Abdi AM, Meštrović A, Gelisen I, Gultekin O, Yavuz DO, Saygı Ş, et al. Introducing a performance-based objective clinical examination into the pharmacy curriculum for students of Northern Cyprus. Trop J Pharm Res. 2017;16(3):681–8.

Lee YS. Proposal of pharmacy school objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) contents and test methods. Korean J Clin Pharm. 2020;30(2):127–33.

Han N, Lee JY, Gwak HS, Lee BK, Lee YS, Lee S, et al. Selection of tasks for assessment of pharmacy clinical performance in Korean pharmacist licensure examination: results of an expert survey. Korean J Clin Pharm. 2017;27(3):119–26.

World Health Organization. The role of the pharmacist in the health care system. World Health Organization. 1997. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63817. Accessed 22 Feb 2022.

Sohn DH. A study on the improvement of the National Pharmacists Examination System in South Korea. Korea Health Personnel Licensing Examination Institute. 2017.

Pharmacy Practice Division of the Korean Association of Pharmacy Education. Clinical Pharmacy Practice. Shinilbooks. 2020.

Korean College of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 4th ed. Shinilbooks. 2017.

Olsen AA, Wolcott MD, Haines ST, Janke KK, McLaughlin JE. How to use the Delphi method to aid in decision making and build consensus in pharmacy education. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2021;13(10):1376–85.

Khan KZ, Ramachandran S, Gaunt K, Pushkar P. The Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE): AMEE Guide No. 81. Part I: an historical and theoretical perspective. Med Teach. 2013;35(9):e1437-46.

Pincus K, Hammond AD, Reed BN, Feemster AA. Effect of advanced pharmacy practice experience grading scheme on residency match rates. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(4):6735.

McCann AL, Maddock CP, Schneiderman ED. A comparison of the clinical performance of students in two grading systems: letter and pass-fail. J Dent Hyg. 1990;64(7):332–8.

Heyliger S, Hudson D. An introduction to test planning, creating test items and conducting test item analysis. Part II: Center for Teaching Excellence, Hampton University; 2016.

Sim SM, Rasiah RI. Relationship between item difficulty and discrimination indices in true/false-type multiple choice questions of a para-clinical multidisciplinary paper. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2006;35(2):67–71.

American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP guidelines on pharmacist-conducted patient education and counseling. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1997;54:431–4.

Lee B. A study on feasibility and implementation of pharmacy performance examination. Korea Health Personnel Licensing Examination Institute. 2015.

Naughton CA. Patient-centered communication. Pharmacy. 2018;6:18.

Tokunaga J, Takamura N, Ogata K, Setoguchi N, Utsumi M, Kourogi Y, et al. An advanced objective structured clinical examination using patient simulators to evaluate pharmacy students’ skills in physical assessment. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(10):184.

Lin CW, Chang EH, Clinciu DL, Peng YT, Huang WC, Wu CC, et al. Using modified information delivery to enhance the traditional pharmacy OSCE program at TMU - a pilot study. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2018;158:147–52.

Croft H, Gilligan C, Rasiah R, Levett-Jones T, Schneider J. Current trends and opportunities for competency assessment in pharmacy education-a literature review. Pharmacy (Basel). 2019;7(2):67.

Przymuszala P, Marciniak-Stepak P, Cerbin-Koczorowska M, Borowczyk M, Cieslak K, Szlanga L, et al. “Difficult conversations with patients” - a modified group objective structured clinical experience for medical students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):5772.

Hadi MA, Ali M, Haseeb A, Mohamed MMA, Elrggal ME, Cheema E. Impact of test anxiety on pharmacy students’ performance in objective structured clinical examination: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Pharm Pract. 2018;26(2):191–4.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge with thanks the support of all actors and staff members involved in the OSCE. We also thank all students and assessors who participated in this study.

Funding

This research was funded by the Korean Association of Pharmacy Education (KAPE) 2020 Research grant, but this manuscript does not represent the KAPE’s opinions or views.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the design of the study, investigation, and data analysis; Y-KS, YSL and HK for the recruitment of participants; Y-KS and HK for analysis and interpretation of data. Y-KS and HK have drafted the work or substantively revised it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sookmyung Women’s University (IRB No. SMWU-2007-HR-066, 17 Aug 2020). We provided sufficient information to the participants, and then written informed consent was obtained. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, YK., Chung, E.K., Lee, Y.S. et al. Objective structured clinical examination as a competency assessment tool of students’ readiness for advanced pharmacy practice experiences in South Korea: a pilot study. BMC Med Educ 23, 231 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04226-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04226-z