Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to determine if minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for rectal cancer is non-inferior to open surgery (OPEN) regarding adequacy of cancer resection in a population based setting.

Methods

All 9,464 patients diagnosed with rectal cancer 2012–2018 who underwent curative surgery were included from the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry. Primary outcomes: Positive circumferential resection margin (CRM < 1 mm) and positive resection margin (R1). Non-inferiority margins used were 2.4% and 4%. Secondary outcomes: 30- and 90-day mortality, clinical anastomotic leak, re-operation < 30 days, 30- and 90-day re-admission, length of stay (LOS), distal resection margin < 1 mm and < 12 resected lymph nodes. Analyses were performed by intention-to-treat using unweighted and weighted multiple regression analyses.

Results

The CRM was positive in 3.8% of the MIS group and 5.4% of the OPEN group, risk difference -1.6% (95% CI -1.623, -1.622). R1 was recorded in 2.8% of patients in the MIS group and in 4.4% of patients in the OPEN group, risk difference -1.6% (95% CI -1.649, -1.633). There were no differences between the groups in adjusted unweighted and weighted analyses. All analyses demonstrated decreased mortality and re-admissions at 30 and 90 days as well as shorter LOS following MIS.

Conclusions

In this population based setting MIS for rectal cancer was non-inferior to OPEN regarding adequacy of cancer resection with favorable short-term outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for rectal cancer is widely used with well recognized improved short-term outcomes such as less postoperative pain, less blood loss, faster recovery and shorter hospital stay when compared to open surgery (OPEN) [1,2,3,4]. However, randomised controlled trials have reported conflicting results with regard to the oncological outcomes of the two surgical techniques. The initial randomized trials comparing MIS and OPEN demonstrated similar short- and long-term oncological outcomes [5,6,7]. Two more recent randomised controlled trials were not able to demonstrate non-inferiority for MIS compared to OPEN for rectal cancer with regard to the composite outcome ‘successful resection’ [8, 9]. Neither study was powered to show non-inferiority for the two year follow up outcomes but no significant difference in rates of local recurrence, disease free or overall survival were reported. The latest published randomised controlled trial compared MIS with OPEN surgery for low rectal cancer and found similar short-term pathological and surgical outcomes [10]. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews have also reported diverging results regarding non-inferiority when comparing adequacy of cancer resection following MIS and OPEN surgical technique for rectal cancer [3, 11, 12]. Large cohort and population based studies have however supported the oncological safety in the use of MIS compared to OPEN both the adequacy of cancer resection and long-term oncological outcome [13,14,15,16].

The use of MIS for rectal cancer has increased in Sweden with 26% of elective resections performed using MIS in 2014 and 63% in 2018. A substantial and increasing part of all rectal cancer resections have been performed using robotic assisted laparoscopic technique (ROBOT) in Sweden, 9% in 2014 and 38% in 2018. It has been argued that ROBOT has potential technical benefits including the use of 3D imaging and articulating instruments. However, none of these advantages have shown to improve adequacy of cancer resection or long-term oncological outcomes when compared to OPEN and laparoscopic surgery [17,18,19]. Neither has any difference been found when comparing ROBOT to conventional laparoscopic surgery with regard to conversion rate, with the drawback of longer operating times [19, 20].

Furthermore, the results reported from randomised controlled trials reflect the oncological outcomes when operated on by colorectal surgeons highly specialized in minimally invasive surgery. Thus, little is known of the oncological outcomes when comparing MIS and OPEN surgery for rectal cancer in a standard care setting.

The objective of this study with a non-inferiority design was to determine if MIS for rectal cancer is non-inferior to OPEN for adequacy of cancer resection in routine healthcare by using data from high quality population based registries, including all tumour stages undergoing curative surgery. Secondary objectives were to compare short-term mortality and morbidity between the groups.

Methods

Study population and variables

In this population based study data was retrieved from the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry (SCRCR) with 98.8% completeness for rectal cancer and combined with data from the National Patient Registry (NPR) based on the unique Swedish identification number for outcomes on 30- and 90-day mortality and re-admission [21]. The NPR registers all in- and out-patient health care from 2001 onwards, and the reliability of the registry has been deemed as high through external validation [22].

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was obtained from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority in Uppsala, Dnr 2018/129 and Dnr 2019–01787. Informed consent was waived as the study is an observational study using prospectively recorded registry data.

All patients diagnosed with rectal cancer from 1st of January 2012 up until 31st of December 2018 who subsequently underwent abdominal resection with curative intent were retrieved from the SCRCR. All cancer stages were included as long as curative intent was intended. Locally resected rectal cancers were not included.

Primary outcome was positive CRM and R1 resection. In the SCRCR, positive CRM is defined as tumour < 1 mm from resection margin and R1 resection is defined as tumour cells in the margin of resection. Patients with resection margins recorded in the SCRCR as “uncertain” or “unable to comment” or “missing” were all defined as missing in the analyses. Secondary outcomes were 30- and 90-day mortality, anastomotic leak and re-operation within 30 days, 30- and 90-day re-admission, LOS, positive distal resection margin (DRM) defined as < 1 mm and less than 12 lymph nodes in the surgical specimen as reported in the SCRCR and NPR. The conversion rate was recorded in the MIS group. Anastomotic leak has no formal definition in the SCRCR, but is nearly always a clinical anastomotic leak and is reported in the registry using a checkbox (yes/no) alternative. All data in the SCRCR is reported and recorded electronically.

In the adjusted analyses the type of surgery, the American Society of Anesthesiologists classification (ASA), age, body mass index (BMI), sex and clinical tumour stage (cTNM) were considered confounding variables for short-term mortality, morbidity and LOS. Type of surgery included anterior resection (AR), abdominoperineal resection (APR) and Hartmann’s procedure. Year of surgery was also deemed to be a potential confounding variable and adjusted for in the analyses. The outcomes CRM, R1 and DRM were further adjusted for cT stage, cN stage, presence of vascular and perineural invasion indicating more advanced tumours. Where cT and cN were missing yp/pT and yp/pN were used.

Conventional laparoscopic (LAP) and robot assisted laparoscopic surgery (ROBOT) were analysed as one group (MIS). ROBOT has been registered in the SCRCR since 2014 and a subgroup analysis was performed comparing ROBOT and OPEN between 2014 to 2018.

Statistical analysis

A statistical analysis plan was agreed upon prior to analysing data. Analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Baseline characteristics of patients were presented as frequencies and percentages or median with interquartile range (IQR). Differences between groups were reported with p-values using Chi-square test for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. In the multiple regression analyses the following variables were adjusted for: type of surgery, ASA class, age, BMI, sex, cTNM and year of surgery. CRM, R1 and DRM were further adjusted for: cT stage, cN stage, proportion of vascular- and perineural invasion. Binary outcomes were analysed using logistic regression and continuous outcomes were log transformed before linear regression was performed. A second inverse probability treatment weighted analysis was performed using propensity scores. Propensity scores were determined using a logistic regression model adjusting for previously identified potential confounders. Non-inferiority was assessed by risk difference analyses with 95% confidence intervals using the predefined non-inferiority margin of 2.4% for CRM as suggested by the Delphi consensus consisting of rectal cancer experts worldwide and for R1 we used the cumulative figure suggested for CRM and DRM 4% [23]. All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 25.0 ®.

Results

Study population

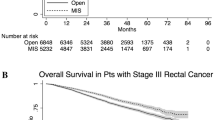

A total of 9464 patients diagnosed 2012–2018 with rectal cancer and receiving resection surgery with curative intent were included from the SCRCR. MIS was performed in 38% of cases, the proportion of patients undergoing MIS increased over the time period and the conversion rate decreased from 20% in 2012 to 12% in 2019 (Fig. 1). The OPEN group included a higher proportion of male patients and a higher proportion of ASA III-IV patients compared to the MIS group (Table 1). The OPEN group displayed more advanced clinical T stage, N stage and TNM stage including more high-grade tumours and a higher proportion of patients had received neoadjuvant treatment compared to the MIS group (Tables 1 and 2). The groups were not statistically significantly different with regard to age, BMI, tumour height, vascular invasion or perineural invasion (Tables 1 and 2). APR represented 38.5% of resections in both groups but Hartmann’s procedure was more frequently performed in the OPEN group (Table 2). A higher proportion of MIS underwent AR compared to the OPEN group and diverting ileostomies were more common in the MIS group (P < 0.001) (Table 2). Intraoperative bowel perforations were more frequent in the OPEN 5.1% vs. MIS 3.7% but perforations close to the tumour did not differ between the two groups (P = 0.134) (Table 2). The MIS group demonstrated statistically significantly less bleeding but longer operating times compared to the OPEN group (Table 2).

Pathology outcomes

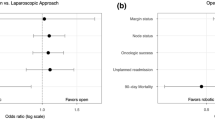

A positive CRM, i.e., less than 1 mm was reported in 135 patients (3.8%) of patients who had undergone MIS compared to 315 patients (5.4%) of patients who had undergone OPEN with a risk difference of -1.6% (95% CI -1.623, -1.622, P < 0.001) (Table 3). The upper limit of the confidence interval was below the pre-determined non-inferiority margin of 2.4%. A positive margin (R1) was reported in 2.8% of patients in the MIS group compared to 4.4% in the OPEN group with a risk difference of -1.6% (95% CI -1.649, -1.633, P < 0.001) (Table 3). This confidence interval was below the non-inferiority margin of 4%. Neither of the confidence intervals included 0 and both P-values were < 0.001 indicating superiority for MIS compared to OPEN. However, in both the unweighted and weighted adjusted regression analyses there was no statistically significant difference in positive CRM (P = 0.101 and P = 0.095) (Table 4). Neither was there a statistically significant difference in R1 resections in the adjusted unweighted and weighted analyses (P = 0.083 and P = 0.061) when comparing the two groups (Table 4). No significant between-group differences in rates of positive DRM or in rate of specimens containing less than 12 lymph nodes was seen in the adjusted analyses (Table 4).

Clinical outcomes

The 30- and 90-day mortality were statistically significantly lower in the MIS group (30-day; 0.5% and 90-day; 1.0%) compared to the OPEN group (30-day; 1.2% and 90-day; 2.0%) in the non-adjusted (30-day; P = 0.002 and 90-day; P < 0.001), adjusted unweighted (30-day; P = 0.014 and 90-day; P = 0.001) and weighted analyses (30-day; P = 0.025 and 90-day; P = 0.001) (Table 4). Similarly, 30- and 90-day readmission were less common in the MIS group compared to the OPEN group (Table 4). There was no significant difference in anastomotic leak, nor reoperation within 30-days comparing MIS and OPEN in the adjusted unweighted and weighted analyses (Table 4). Length of hospital stay was shorter in the non-adjusted and adjusted unweighted and weighted analyses (P < 0.001) following MIS (median 7 days vs 9 days) (Table 5).

Subgroup analyses – ROBOT vs OPEN

In the subgroup analyses 2014 to 2018 we found that 19.6% of patients underwent LAP, 26.5% ROBOT and 53.9% OPEN. The baseline characteristics comparing MIS vs OPEN revealed a higher proportion of male patients, higher ASA and lower tumours, similar selection have been previously reported (Table 6) [24, 25]. Patients in the OPEN group again displayed more advanced cancer stages along with other features suggestive of more aggressive tumour biology (Tables 6 and 7). ROBOT and LAP cases had less bleeding but longer operating times, the longest median operating time was in the ROBOT group (Table 7). The conversion rate was significantly higher in LAP compared to ROBOT (18.5% vs 10.7%, P = < 0.001) (Table 7).

Comparison of ROBOT to OPEN revealed no statistically significant difference in CRM < 1 mm (P = 0.840) or in R1 resections (P = 0.738) in the adjusted analyses. Neither was there a difference in the pathology assessment with regard to DRM < 1 mm or a specimen including < 12 resected lymph nodes (Table 8). However, 90-day mortality and 30 and 90-day re-admissions were significantly higher in the unadjusted and adjusted analyses following OPEN compared to ROBOT (Table 8). No difference was noted in the adjusted analyses for 30-day mortality, anastomotic leak, reoperation within 30 days between the two groups but LOS was shorter following ROBOT versus OPEN (7 vs 9 days, p < 0.001) (Table 9).

Discussion

This population based study indicated that MIS is non-inferior to OPEN for adequacy of cancer resection in routine healthcare. This is found partly through no difference in positive CRM and R1 in the adjusted unweighted and weighted analyses. MIS also demonstrated a significantly lower 30- and 90-day mortality and re-admission rates compared to OPEN, both in the adjusted unweighted and weighted analyses. Previously well recognized advantages of MIS over OPEN were confirmed including less bleeding and shorter hospital stay.

Positive CRM and positive DRM are both recognized as important prognosticators for local recurrence following rectal cancer resection [26,27,28]. The rates of positive CRM and positive DRM in this study are similar to rates reported by the most recent randomised controlled trials and lower compared to rates previously reported in large cohort and population based studies [14, 28, 29]. In comparison to the randomised trials, this population based study included a smaller proportion of low tumours (20.7% MIS and 20.8% OPEN) which facilitates the possibility of achieving an adequate cancer resection. On the other hand, and in contrast to randomised trials, this study also included cT4 tumours (11.1% MIS and 22.1% OPEN) which is considered a risk factor for positive resection margins. A population based study from the Netherlands reported positive CRM in as many as 13.9% of TME resections for cT4 rectal cancers [30]. Other known risk factors for a positive margin include previous radiochemotherapy, T3 tumours, N stage 1–2, APR and high BMI [31, 32]. There were similar percentages of cT3 tumours and cN stage 1–2 in our study, but a higher proportion of preoperative radiation or radiochemotherapy in all groups when comparing with the randomised trials. A higher proportion in our study have undergone APR, though this study included by comparison a smaller proportion of low tumours. This is in keeping with previously reported higher rates of APR in Sweden compared to the Netherlands [33]. Furthermore, reflective of the Swedish population, this study reports a relatively low median BMI when compared to many other western populations. This population based study mirrors the real world and the distribution of disease stage, tumour height and the use of preoperative radiation and chemoradiation reflects this. However, the distribution of these important characteristics differ from those seen in non-population based studies including randomised controlled trials which makes direct comparison of outcomes difficult.

The 30- and 90-day mortality is lower than previously described in cohort studies and population based studies and similar to rates reported in randomised controlled trials [1, 4, 9, 29, 34, 35]. The explanation for this is likely multifactorial, factors that might play a role are: the presence of a gradual centralisation process, appropriate patient selection for surgery and the proportion of patients undergoing resection [36,37,38]. Furthermore, patients’ comorbidities as well as their age have also been shown influence short term mortality. Sweden has previously been demonstrated to perform a higher proportion of rectal cancer resections when compared to England, Denmark and Norway, especially in the older population [39]. It is also worth mentioning that most elective rectal cancer resections in Sweden are performed by specialized colorectal surgeons. The favourable morbidity and mortality rates following MIS compared to OPEN are in accordance with those previously reported in large cohort and population based studies [15, 34, 40, 41]. Our subgroup analyses comparing ROBOT and OPEN found similar outcomes for ROBOT as for MIS including decreased 90-day mortality and decreased 30- and 90-day readmission. A decreased 30- and 90-day readmission in the MIS group has been suggested by previous population based studies [40, 41].

The rate of diverting stomas are notably higher than those reported in other studies, which is in keeping with results previously reported comparing Swedish and Dutch data.

This could in part be explained by the frequent use of radiation in accordance with the Swedish national treatment guidelines for rectal cancer. Also, many centers in Sweden have accepted the results from the RECTODES trial that diverting loop stomas are reported to decrease the rate of symptomatic anastomotic leakage [42, 43]. A higher rate of conversion in the MIS group when compared to the randomized controlled trials was also found, with lower figures noted in the ROBOT group. The rate of conversion rate is used to assess the MIS learning curve, and ROBOT is considered to have a shorter learning curve compared to LAP. This could in part explain the differences between the two groups, despite ROBOT being introduced at a later stage. The centralisation for surgical treatment of rectal cancer in Sweden started in the early 2000s, though, only half of all rectal resections are performed in high volume hospitals with a yearly volume of around 50 cases, which could in part explain the higher conversion rate [33, 37]. The number of resections per surgeon is also known to influence conversion rate, however, this information is not readily available in the SCRCR. Nevertheless, this study exhibits a high proportion of adequate cancer resection and favourable short-term outcomes, indicating a safe implementation of MIS in Sweden.

Recognised drawbacks with MIS include longer operating time and higher costs for the health care sector although without a cost-difference in long- term societal perspective [44]. Studies have however invariably reported higher hospital costs related to robotic assisted laparoscopic surgery when compared to conventional laparoscopic surgery [45, 46]. We have not evaluated the health economic aspects in this study but can confirm longer operating times.

Strengths of this study include the population based setting and the combination of two high quality registers including close to all patients who have undergone curative surgery for rectal cancer in Sweden 2012–2018 with a 90 day follow up. Another strength is the consistency of the results following two different statistical methods indicating the robustness of the findings.

Limitations of this study are similar to those of other population-based register studies including the potential for selection bias and residual confounding. The indications for the choice of MIS or OPEN surgery were not available. However, the use of different statistical models demonstrating comparable results may have reduced the potential problem of residual confounding.

Conclusions

In conclusion this population based study indicated that MIS is non-inferior to OPEN for rectal cancer with regard to adequacy of cancer resection in routine healthcare. It also demonstrated favourable short-term outcomes including significantly less bleeding, shorter hospital stay lower and lower 30- and 90-day mortality and re-admission rate. This study support that MIS for rectal cancer is a safe oncologic procedure when performed by experienced surgeons in routine health care.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are from the National Patient Registry and the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry under license for the current study. Data are available from the corresponding author with the permission of National Patient Registry (https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/en/) and the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry (https://scrcr.se).

Abbreviations

- CRM:

-

Circumferential resection margin

- R1:

-

Positive resection margin

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

- MIS:

-

Minimally invasive surgery

- OPEN:

-

Open surgery

- ROBOT:

-

Robotic assisted laparoscopic surgery

- SCRCR:

-

Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry

- NPR:

-

National Patient Register

- DRM:

-

Distal resection margin

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists classification

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- cTNM:

-

Clinical tumour stage

- AR:

-

Anterior resection

- APR:

-

Abdominoperineal resection

- LAP:

-

Laparoscopic surgery

References

van der Pas MH, Haglind E, Cuesta MA, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer (COLOR II): short-term outcomes of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(3):210–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70016-0.

Vennix S, Pelzers L, Bouvy N, et al. Laparoscopic versus open total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005200.pub3.

Martinez-Perez A, Carra MC, Brunetti F, de'Angelis N. Short-term clinical outcomes of laparoscopic vs open rectal excision for rectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(44):7906–7916. doi:https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i44.7906

Kang SB, Park JW, Jeong SY, et al. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid or low rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): short-term outcomes of an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(7):637–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70131-5.

Jeong S-Y, Park JW, Nam BH, et al. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid-rectal or low-rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): survival outcomes of an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(7):767–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(14)70205-0.

Bonjer HJ, Deijen CL, Abis GA, et al. A randomized trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(14):1324–32. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1414882.

Jayne DG, Guillou PJ, Thorpe H, et al. Randomized Trial of Laparoscopic-Assisted Resection of Colorectal Carcinoma: 3-Year Results of the UK MRC CLASICC Trial Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(21):3061–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2006.09.7758.

Stevenson AR, Solomon MJ, Lumley JW, et al. Effect of Laparoscopic-Assisted Resection vs Open Resection on Pathological Outcomes in Rectal Cancer: The ALaCaRT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;314(13):1356–63. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.12009.

Fleshman J, Branda M, Sargent DJ, et al. Effect of Laparoscopic-Assisted Resection vs Open Resection of Stage II or III Rectal Cancer on Pathologic Outcomes: The ACOSOG Z6051 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;314(13):1346–55. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10529.

Jiang WZ, Xu JM, Xing JD, et al. Short-term Outcomes of Laparoscopy-Assisted vs Open Surgery for Patients With Low Rectal Cancer: The LASRE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(11):1607–15. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.4079.

Acuna SA, Chesney TR, Ramjist JK, Shah PS, Kennedy ED, Baxter NN. Laparoscopic Versus Open Resection for Rectal Cancer: A Noninferiority Meta-analysis of Quality of Surgical Resection Outcomes. Ann Surg. 2019;269(5):849–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003072.

Martinez-Perez A, Carra MC, Brunetti F, de’Angelis N. Pathologic Outcomes of Laparoscopic vs Open Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA surgery. 2017;152(4):e165665. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2016.5665.

Lujan J, Valero G, Biondo S, Espin E, Parrilla P, Ortiz H. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer: results of a prospective multicentre analysis of 4,970 patients. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(1):295–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2444-8.

Klein MF, Vogelsang RP, Gögenur I. Circumferential Resection Margin After Laparoscopic and Open Rectal Resection: A Nationwide Propensity Score Matched Cohort Study. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2019;62(10):1177–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/dcr.0000000000001460. (Diseases of the Colon & Rectum).

Schnitzbauer V, Gerken M, Benz S, et al. Laparoscopic and open surgery in rectal cancer patients in Germany: short and long-term results of a large 10-year population-based cohort. Surg Endosc. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-06861-4.

Dehlaghi Jadid K, Cao Y, Petersson J, Angenete E, Matthiessen P. Long term oncological outcomes for laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer - A population-based nationwide noninferiority study. Colorectal Dis. 2022;24(11):1308–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.16204.

Jones K, Qassem MG, Sains P, Baig MK, Sajid MS. Robotic total meso-rectal excision for rectal cancer: A systematic review following the publication of the ROLARR trial. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;10(11):449–64. https://doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v10.i11.449.

Prete FP, Pezzolla A, Prete F, et al. Robotic Versus Laparoscopic Minimally Invasive Surgery for Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann Surg. 2018;267(6):1034–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002523.

Park JS, Lee SM, Choi GS, et al. Comparison of Laparoscopic Versus Robot-Assisted Surgery for Rectal Cancers: The COLRAR Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2023;278(1):31–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000005788.

Jayne D, Pigazzi A, Marshall H, et al. Effect of Robotic-Assisted vs Conventional Laparoscopic Surgery on Risk of Conversion to Open Laparotomy Among Patients Undergoing Resection for Rectal Cancer: The ROLARR Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318(16):1569–80. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7219.

Moberger P, Skoldberg F, Birgisson H. Evaluation of the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry: an overview of completeness, timeliness, comparability and validity. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(12):1611–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186x.2018.1529425.

Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):450. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-450.

Acuna SA, Chesney TR, Amarasekera ST, Baxter NN. Defining Non-inferiority Margins for Quality of Surgical Resection for Rectal Cancer: A Delphi Consensus Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(11):3171–8. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6639-7.

Matsuyama T, Endo H, Yamamoto H, et al. Outcomes of robot-assisted versus conventional laparoscopic low anterior resection in patients with rectal cancer: propensity-matched analysis of the National Clinical Database in Japan. BJS Open. 2021;5(5)doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsopen/zrab083

Giesen LJX, Dekker JWT, Verseveld M, et al. Implementation of robotic rectal cancer surgery: a cross-sectional nationwide study. Surg Endosc. 2023;37(2):912–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09568-1.

Nagtegaal ID, Quirke P. What is the role for the circumferential margin in the modern treatment of rectal cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(2):303–12. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2007.12.7027.

Adam IJ, Mohamdee MO, Martin IG, et al. Role of circumferential margin involvement in the local recurrence of rectal cancer. Lancet. 1994;344(8924):707–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92206-3.

Galvez A, Biondo S, Trenti L, et al. Prognostic Value of the Circumferential Resection Margin After Curative Surgery For Rectal Cancer: A Multicenter Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000002294

Manchon-Walsh P, Aliste L, Biondo S, et al. A propensity-score-matched analysis of laparoscopic vs open surgery for rectal cancer in a population-based study. Colorectal Dis. 2019;21(4):441–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.14545.

de Nes LCF, Drager LD, Verstegen MG, et al. Persistent High Rate of Positive Margins and Postoperative Complications After Surgery for cT4 Rectal Cancer at a National Level. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2021;64(4):389–98. https://doi.org/10.1097/dcr.0000000000001855. (Diseases of the Colon & Rectum).

Kong JC, Prabhakaran S, Choy KT, Larach JT, Heriot A, Warrier SK. Oncological reasons for performing a complete mesocolic excision: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2021;91(1–2):124–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.16518.

Warrier SK, Kong JC, Guerra GR, et al. Risk Factors Associated With Circumferential Resection Margin Positivity in Rectal Cancer: A Binational Registry Study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(4):433–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000001026.

Warps AK, Saraste D, Westerterp M, et al. National differences in implementation of minimally invasive surgery for colorectal cancer and the influence on short-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2022;36(8):5986–6001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08974-1.

Panis Y, Maggiori L, Caranhac G, Bretagnol F, Vicaut E. Mortality after colorectal cancer surgery: a French survey of more than 84,000 patients. Ann Surg. 2011;254(5):738–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31823604ac. (discussion 743-4).

Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, et al. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9472):1718–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(05)66545-2.

Archampong D, Borowski D, Wille-Jorgensen P, Iversen LH. Workload and surgeon's specialty for outcome after colorectal cancer surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD005391. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005391.pub3

Smedh K, Olsson L, Johansson H, Aberg C, Andersson M. Reduction of postoperative morbidity and mortality in patients with rectal cancer following the introduction of a colorectal unit. Br J Surg. 2001;88(2):273–7. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01675.x.

Layfield DM, Flashman KG, Benitez Majano S, et al. Changing patterns of multidisciplinary team treatment, early mortality, and survival in colorectal cancer. BJS Open. 2022;6(5)doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsopen/zrac098

Benitez Majano S, Di Girolamo C, Rachet B, et al. Surgical treatment and survival from colorectal cancer in Denmark, England, Norway, and Sweden: a population-based study. The Lancet Oncology. 2019;20(1):74–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30646-6.

Mroczkowski P, Hac S, Smith B, Schmidt U, Lippert H, Kube R. Laparoscopy in the surgical treatment of rectal cancer in Germany 2000–2009. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(12):1473–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03058.x.

Kolfschoten NE, van Leersum NJ, Gooiker GA, et al. Successful and safe introduction of laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery in Dutch hospitals. Ann Surg. 2013;257(5):916–21. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825d0f37.

Matthiessen P, Hallbook O, Rutegard J, Simert G, Sjodahl R. Defunctioning stoma reduces symptomatic anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection of the rectum for cancer: a randomized multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246(2):207–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180603024.

Gu WL, Wu SW. Meta-analysis of defunctioning stoma in low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: evidence based on thirteen studies. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-014-0417-1.

Gehrman J, Angenete E, Björholt I, Lesén E, Haglind E. Cost-effectiveness analysis of laparoscopic and open surgery in routine Swedish care for colorectal cancer. Surgical Endoscopy. 2020;34(10):4403–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-07214-x.

Jayne D, Pigazzi A, Marshall H, et al. Effect of Robotic-Assisted vs Conventional Laparoscopic Surgery on Risk of Conversion to Open Laparotomy Among Patients Undergoing Resection for Rectal Cancer. JAMA. 2017;318(16):1569. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7219.

Pai A, Marecik SJ, Park JJ, Melich G, Sulo S, Prasad LM. Oncologic and Clinicopathologic Outcomes of Robot-Assisted Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(7):659–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000385.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg. This study was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society 19 0333 Pj, ALF Sahlgrenska University Hospital, ‘Agreement concerning research and education of doctors’ ALFGBG-716581, Anna-Lisa and Bror Björnsson’s Foundation. The funding sources had no influence on data acquisition, data management, analyses and interpretations of data or writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P. was involved in the writing of the statistical analysis plan, the datacleaning, the analysing and the interpretation of data and results as well as the writing of the manuscript and the preparation of figures and tables. All authors were involved in the writing of the statistical analysis plan, interpretation of data and results including the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority through the Regional Ethics Board of Uppsala, Dnr 2018/129 and Dnr 2019–01787. The Regional Ethics Board of Uppsala waived consent as the study is an observational study using prospectively recorded registry data. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Petersson, J., Matthiessen, P., Jadid, K.D. et al. Short-term results in a population based study indicate advantage for minimally invasive rectal cancer surgery versus open. BMC Surg 24, 52 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-024-02336-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-024-02336-z