Abstract

Background

Appendicitis in elderly patients is associated with increased risk of postoperative complications. The choice between laparoscopy and open appendectomy remains controversial in treating elderly patients with appendicitis.

Methods

Comprehensive search of literature of MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library and ClinicalTrials was done in January 2019. Studies compared laparoscopy and open appendectomy for elderly patients with appendicitis were screened and selected. Postoperative mortality, complications, wound infection, intra-abdominal abscess and operating time, length of hospital stay were extracted and analyzed. The Review Manage 5.3 was used for data analysis.

Results

Twelve studies with 126,237 patients in laparoscopy group and 213,201 patients in open group. Postoperative mortality was significantly lower following laparoscopy (OR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.28 to 0.39). Postoperative complication and wound infection were reduced following laparoscopy ((OR, 0.65 95% CI, 0.62 to 0.67; OR,0.27, 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.32). Intra-abdominal abscess was similar between LA and OA (OR,0.44;95% CI, 0.19 to 1.03). Duration of surgery was longer following laparoscopy and length of hospital stay was shorter following laparoscopy (MD, 7.25, 95% CI, 3.13 to 11.36; MD,-2.72, 95% CI,-3.31 to − 2.13).

Conclusions

Not only laparoscopy is safe and feasible, but also it is related with decreased rates of mortality, post-operative morbidity and shorter hospitalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Appendicitis is the most common cause of abdominal pain and a prevalent reason for emergency surgery. The risks of developing appendicitis through lifetime is approximately 8.6% for male and 6.7% for female [1]. Aging of population has been a serious problem in many counties, according to prediction, by 2050, the population of elderly people (age more than 65) will be around 498 million in China [2]. The prevalence of appendicitis will increase following the population changes [3]. Previous studies demonstrated that appendicitis in elderly are associated with higher risk of perforation and complications due to more comorbidities and more challenge of accurate diagnosis [4, 5]. Therefore, precise diagnosis coupled with appropriate procedure are crucial for treating appendicitis in elderly population [6, 7].

Laparoscopic appendectomy (LA) was first mentioned by Kurt Semm in 1983 [8], since that, numerous studies have focused on the comparison of laparoscopy and conventional open appendectomy (OA). In adults, LA is associated with less postoperative pain, faster recovery and less surgical complications. However, there are a great amount of debate concerning postoperative intra-abdominal abscess (IAA) after LA. A recent Cochrane review has demonstrated increased risk of IAA following LA, on the other hand, a cumulative meta-analysis by Ukai et al. demonstrated that increased risk of IAA following LA disappeared in studies published after 2001 [9,10,11]. The use of LA in elderly patients is still under debate. Previous studies suggested the same advantages of LA for elderly patients as for adults whereas some argued that the use of carbon dioxide for pneumoperitoneum increasing the risk of cardiovascular comorbidities.

In the present study, we searched several database for studies of LA versus OA for elderly patients and tried to reach a conclusion based on quantification analysis.

Methods

The study was conducted following the published protocol for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [12].

Search & Study selection

Comprehensive literature search of several database (MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, Clinical Trials) of relevant studies was conducted in Jan. 2019. The searching strategy was based on Mesh terms plus entry terms for each component of the PICOS question [13]. The exact searching terms were shown in Additional file 1. The reference lists of relevant studies were also screened. We also contacted the corresponding author for more information if necessary.

Selecting and screening of the studies were conducted by two independent reviewers (DY W and T D). When the two independent authors disagree with each other while screening, a call of term meeting was needed to discuss whether we should include the study or not.

Eligibility criteria

Identified studies were collected for further selection if they meet the following eligibility criteria: comparison studies focused on laparoscopy and open appendectomy; enrolled patients older than 65 years old; complete records of clinical data and postoperative follow up records.

Data collection & grading of individual study

The following data was extracted from the enrolled studies: name of the study, country, type of study design, baseline characteristic of the participants and outcomes. Assessing the quality of the study was based on the type of the study, for observational studies, we used the Newcastle Ottawa Quality assessment Scale [14] (NOS Scale).

Data analysis

We performed data analysis by using Review Manager 5.3 Software. The choice between Fix or Random effects model was based on the degree of heterogeneity. The heterogeneity of the included studies was determined by I2 statistic. If I2 was greater than 70%, we used subgroup analysis to explore the cause of great heterogeneity.

The Peto odds ratio (OR) or Mean difference (MD) was calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous outcomes and continuous outcomes. Funnel plot was conducted to detect publication bias for each pooled outcome.

A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study selection & characteristics

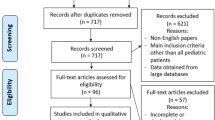

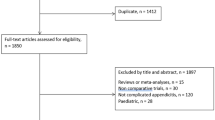

The searching and screening process was shown in Fig. 1. Twelve studies were finally included [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. The basic characteristics of the studies were summarized in Table 1. Two studies used the same database with potential overlap population [21, 23], however, after screening the full texts, we found that these studies reported different outcomes focusing on different aspect of the procedures, so we decided to include the two studies. All included studies were observational studies hence the NOS scale was used for assessment of quality. (Shown in Additional file 2). The quality score of studies varied from 7 to 9.

Postoperative mortality

Six studies reported postoperative mortality data with 125,996 in LA group and 212,940 patients in OA group. Postoperative mortality was significantly reduced following LA (OR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.28 to 0.39, shown in Fig. 2). Moderate heterogeneity was found between the studies (I2 = 42%). Funnel plot for publication bias detection showed no obvious bias in postoperative mortality (Fig. 3).

Overall complications

Eight studies reported overall complication data with 17,806 patients in LA group and 29,526 patients in OA group. Overall complication was significantly reduced following laparoscopy (OR, 0.65 95% CI, 0.62 to 0.67, shown in Fig. 4). We conducted subgroup analysis by dividing the studies into studies containing complicated appendicitis (CA) and studies which did not.

The subgroup analysis showed significantly reduced overall complications following laparoscopy in both subgroups (OR,0.65, 95% CI, 0.62 to 0.68; OR,0.64, 95% CI, 0.57 to 0.71). Funnel plot for publication bias showed asymmetry which indicated publication bias may exist (Fig. 5).

Wound infections

Six studies reported data of wound infection with 18,082 patients in LA group and 28,158 patients in OA group. Wound infection was lower in LA group (OR,0.27, 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.32, shown in Fig. 6). We conducted subgroup analysis. The subgroup analysis showed a reduced rate of wound infection following LA in both subgroups (OR,0.24; 95% CI, 0.20 to 0.30;OR,0.35, 95% CI,0.25 to 0.49). Funnel plot for publication bias showed asymmetry which indicated publication bias may exist (Fig. 7).

Intra-abdominal abscess

Three studies reported data of postoperative intra-abdominal abscess formation. No significant difference was found between LA and OA (OR,0.44; 95% CI, 0.19 to 1.03, shown in Fig. 8). Medium heterogeneity was found (I2 = 53%). Funnel plot for publication bias showed asymmetry which indicated publication bias may exist (Fig. 9).

Duration of surgery

Five studies reported data of operating time with 290 patients in LA group and 289 patients in open group. Operating time was longer following LA (MD, 7.25, 95% CI, 3.13 to 11.36, shown in Fig. 10). Moderate heterogeneity was found (I2 = 44%). Funnel plot for publication bias detection showed no obvious bias in postoperative mortality (Fig. 11).

Length of hospital stay

Eight studies have reported length of hospital stay with 91,618 patients in LA group and 179,569 patients in OA group. Length of hospital stay was significantly shorter following LA (MD,-2.72, 95% CI,-3.31 to − 2.13, shown in Fig. 12). Low heterogeneity was found (I2 = 7%). Funnel plot for publication bias detection showed no obvious bias in postoperative mortality (Fig. 13).

Discussion

Elderly patients with appendicitis are associated with higher perforation rate due to atypical symptoms and more comorbidities [27, 28]. Previous studies have demonstrated that postoperative mortality and complication rate were higher in elderly population compared with younger population [29]. The World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) have recommended LA for elderly patients in their Jerusalem guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis [30], however, this recommendation was based on the results from several observational studies without quantitative analysis. As a result, the guideline graded this recommendation as level B, which was generalized from consistent level 2 or 3 (cohort study or case control study) and reflected moderate clinical certainty [31].

Based on our results, the postoperative mortality and complications rate was significantly lower in the LA group. This finding was consistent with adults studies [10]. According to previous studies, death risk of older appendicitis patients is 14 times higher than that of general adult population [32]. With this relatively high risk of mortality, the choice of an appropriate procedure is critical. Laparoscopy seemed to be safer than conventional open procedure due to its low invasiveness and faster recovery. However, the existed studies have also pointed out that in cases of complicated appendicitis, more OA is performed due to more straightforward operating view of the abdominal adhesion and peritonitis. The relatively high postoperative mortality and complication in OA group may be partly accounted for a larger proportion of complicated appendicitis. Perforation rate was also higher in elderly population, due to the atypical symptoms and usually sicker condition of elderly patients, misdiagnosis of a perforated appendix happened in nearly a third of the elderly patients resulting in delay of appropriate treatment [3]. The use of laparoscopy combined with preoperative CT may helped to reduce the rate of misdiagnosis hence prevent perforation. Wound infection was lower following LA in our results. Many studies have demonstrated that compared with OA, LA was associated with less wound infection [33] The use of a wound protective plastic bag when moving out the inflamed appendix in LA may be the primary reason for this result [34]. Less surgical incision, more uncomplicated appendicitis cases in LA group may also account for the lower wound infection rate of LA. The superiority of LA in reducing wound infection was shown in both studies containing CA and uncomplicated appendicitis, existed study suggested that delay of treatment and general condition contributed mostly to wound infection [35]. Our study found no significant difference between LA and OA concerning intra-abdominal abscess, which was inconsistent with previous studies. Limited extracted data pooled in this outcome may be the reason for this finding.

Great heterogeneity is the primary cause to diminish the credibility of a pooled outcome in a meta-analysis [36]. As in the present study, heterogeneity existed in some pooled outcomes. The different postoperative follow up period, the definition of postoperative complication may be the reasons for existed heterogeneity among the studies. Another reason may be the severity of appendicitis in each study, as the range of acute appendicitis covers from uncomplicated appendicitis to abscess and perforation. The precise diagnosis of the type of appendicitis is mainly depended on postoperative pathology, which makes preoperative stratification of the patients unpractical.

Duration of surgery was significantly longer in LA group. Many existed RCTs or meta-analysis focused on adults have also demonstrated the same trend in operating time [37]. Longer operating time can be contributed by several factors, the more equipment used and longer setup time in LA procedure, the learning curve of laparoscopy and the status of the appendix. Length of hospital stay was shorter following LA. This results may due to the less invasiveness of the procedure hence faster recovery. Previous studies have also suggested that after LA, patients can return to normal activity and diet earlier than OA [38]. Although we did not analyze the medical charge between the two groups, many studies have demonstrated that even with higher surgical expenses of LA, the shorter postoperative hospital stay endows the total medical charge almost equivalent between LA and OA [39, 40].

The present study has certain limitations. Firstly, due to the low participant rate of elderly patients in RCTs, all of our enrolled studies were retrospectively observational studies. The results may be influenced by selection bias. Secondly, due to the availability of data from enrolled studies, we only analyzed six outcomes. More comparable outcomes like postoperative pain, return to normal activity and readmission were not investigated. Thirdly, some of the enrolled studies included both uncomplicated and complicated appendicitis, the type of appendicitis and comorbidities of the patient can be confounding factors for the results. Fourthly, although we tried to search as comprehensively as possible to avoid publication bias, it was still detected in overall complications, wound infection and intra-abdominal abscess. The results might be exaggerated due to publication bias. Fifth, study by Masoomi et al. and studies by Kim et al. and Moazzez et al. which analyzed data from the National Inpatient sample database (NIS) and National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) may have data overlap. These two database are both primarily composed by hospitals from the United States hence double count of patients may exist in the present meta-analysis.

The current meta-analysis showed that LA is a safe and feasible procedure for elderly appendicitis patients with lower rate of postoperative mortality and complication and shorter hospital stay. Laparoscopy should be recommended to elderly patients when there are no contraindications. However, larger high quality RCTs are still needed to form a more solid conclusion.

Conclusions

For elderly patients with appendicitis, laparoscopy is associated with less postoperative mortality and complication, less wound infection, shorter hospital stay. The use of laparoscopy is safe and feasible for elderly population.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- LA:

-

Laparoscopic appendectomy

- MD:

-

Mean difference

- NOS Scale:

-

Newcastle Ottawa Quality assessment scale

- OA:

-

Open appendectomy

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RCT:

-

Randomized control studies

- WSES:

-

World society of emergency surgery

References

Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):910–25.

Yixiang CYLZH. The aging trend of Chinese population and the prediction of aging population in 2015-2050. Chin J Soc Med. 2018;35(5):480–3.

Storm-Dickerson TL, Horattas MC. What have we learned over the past 20 years about appendicitis in the elderly? Am J Surg. 2003;185(3):198–201.

Bhullar JS, Chaudhary S, Cozacov Y, Lopez P, Mittal VK. Acute appendicitis in the elderly: diagnosis and management still a challenge. Am Surg. 2014;80(11):E295–7.

Gürleyik G, Gürleyik E. Age-related clinical features in older patients with acute appendicitis. Eur J Emerg Med. 2003;10(3):200–3.

Andersson RE. The natural history and traditional management of appendicitis revisited: spontaneous resolution and predominance of prehospital perforations imply that a correct diagnosis is more important than an early diagnosis. World J Surg. 2007;31(1):86–92.

Podda M, Gerardi C, Cillara N, Fearnhead N, Gomes CA, Birindelli A, Mulliri A, et al. Antibiotic treatment and appendectomy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in adults and children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2019.

Semm K. Endoscopic appendectomy. Endoscopy. 1983;15(2):59–64.

Jaschinski T, Mosch C, Eikermann M, Neugebauer EA. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in patients with suspected appendicitis: a systematic review of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:48.

Jaschinski T, Mosch CG, Eikermann M, Neugebauer EA, Sauerland S. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:Cd001546.

Ukai T, Shikata S, Takeda H, Dawes L, Noguchi Y, Nakayama T, Takemura YC. Evidence of surgical outcomes fluctuates over time: results from a cumulative meta-analysis of laparoscopic versus open appendectomy for acute appendicitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:37.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2009;339:b2535.

Baumann N. How to use the medical subject headings (MeSH). Int J Clin Pract. 2016;70(2):171–4.

GA Wells BS, D O'Connell, J Peterson, V Welch, M Losos, P Tugwell. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses [Available from: www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

Yang J, Yu K, Li W, Si X, Zhang J, Wu W, Cao Y. Laparoscopic appendectomy for complicated acute appendicitis in the elderly: a single-center experience. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2017;27(5):366–8.

Masoomi H, Mills S, Dolich MO, Ketana N, Carmichael JC, Nguyen NT, Stamos MJ. Does laparoscopic appendectomy impart an advantage over open appendectomy in elderly patients? World J Surg. 2012;36(7):1534–9.

Ferrarese AG, Martino V, Enrico S, Falcone A, Catalano S, Pozzi G, Marola S, et al. Laparoscopic appendectomy in the elderly: our experience. BMC Surg. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S22.

Ward NT, Ramamoorthy SL, Chang DC, Parsons JK. Laparoscopic appendectomy is safer than open appendectomy in an elderly population. JSLS. 2014;18(3).

Wu SC, Wang YC, Fu CY, Chen RJ, Huang HC, Huang JC, Lu CW, et al. Laparoscopic appendectomy provides better outcomes than open appendectomy in elderly patients. Am Surg. 2011;77(4):466–70.

Paranjape C, Dalia S, Pan J, Horattas M. Appendicitis in the elderly: a change in the laparoscopic era. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(5):777–81.

Kim MJ, Fleming FJ, Gunzler DD, Messing S, Salloum RM, Monson JRT. Laparoscopic appendectomy is safe and efficacious for the elderly: an analysis using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project database. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(6):1802–7.

Harrell AG, Lincourt AE, Novitsky YW, Rosen MJ, Kuwada TS, Kercher KW, Sing RF, et al. Advantages of laparoscopic appendectomy in the elderly. Am Surg. 2006;72(6):474–80.

Ashkan M, Mason RJ, Namir K. Thirty-day outcomes of laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in elderly using ACS/NSQIP database. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(4):1061–71.

Wu TC, Lu Q, Huang ZY, Liang XH. Efficacy of emergency laparoscopic appendectomy in treating complicated appendicitis for elderly patients. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(11):1108–12.

Guller U, Jain N, Peterson ED, Muhlbaier LH, Pietrobon R. Laparoscopic appendectomy in the elderly. Surgery (St Louis). 2004;135(5):479–88.

Wang YC, Yang HR, Chung PK, Jeng LB, Chen RJ. Laparoscopic appendectomy in the elderly. Surg Endosc. 2006;20(6):887–9.

Shchatsko A, Brown R, Reid T, Adams S, Alger A, Charles A. The utility of the Alvarado score in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in the elderly. Am Surg. 2017;83(7):793–8.

Omari AH, Khammash MR, Qasaimeh GR, Shammari AK, Yaseen MK, Hammori SK. Acute appendicitis in the elderly: risk factors for perforation. World J Emerg Surg. 2014;9(1):6.

Segev L, Keidar A, Schrier I, Rayman S, Wasserberg N, Sadot E. Acute appendicitis in the elderly in the twenty-first century. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(4):730–5.

Di Saverio S, Birindelli A, Kelly MD, Catena F, Weber DG, Sartelli M, Sugrue M, et al. WSES Jerusalem guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2016;11:34.

Group LoEW. Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine – Levels of Evidence 2009 [Available from: http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/.

Kraemer M, Franke C, Ohmann C, Qin Y. Acute appendicitis in late adulthood: incidence, presentation, and outcome. Results of a prospective multicenter acute abdominal pain study and a review of the literature. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2000;385(7):470–81.

Athanasiou C, Lockwood S, Markides GA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic versus open Appendicectomy in adults with complicated appendicitis: an update of the literature. World J Surg. 2017;41(12):3083–99.

Southgate E, Vousden N, Karthikesalingam A, Markar SR, Black S, Zaidi A. Laparoscopic vs open appendectomy in older patients. Arch Surg. 2012;147(6):557–62.

Baumann LM, Williams K, Oyetunji TA, Grabowski J, Lautz TB. Optimal timing of postoperative imaging for complicated appendicitis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech Part A. 2018;28(10):1248–52.

Higgins JPT GS. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviewsof interventions version 5.1.0 2011 [updated March 2011. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Dai L, Shuai J. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in adults and children: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5(4):542–53.

Wei B, Qi CL, Chen TF, Zheng ZH, Huang JL, Hu BG, Wei HB. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy for acute appendicitis: a metaanalysis. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(4):1199–208.

Masoomi H, Nguyen NT, Dolich MO, Mills S, Carmichael JC, Stamos MJ. Laparoscopic appendectomy trends and outcomes in the United States: data from the Nationwide inpatient sample (NIS), 2004-2011. Am Surg. 2014;80(10):1074–7.

Yeh CC, Wu SC, Liao CC, Su LT, Hsieh CH, Li TC. Laparoscopic appendectomy for acute appendicitis is more favorable for patients with comorbidities, the elderly, and those with complicated appendicitis: a nationwide population-based study. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(9):2932–42.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

The study was not funded or sponsored by any funding.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DY W and T D performed the searching and screening process, Y S and TT G analyzed the data. DT W and T D, Y S wrote the manuscript together, Y X and Y J supervised and instructed the whole process. All co-authors have read and approved the final submitted manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not required for systematic review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Searching Terms in MEDLINE. (DOCX 12 kb)

Additional file 2:

NOS scale for enrolled studies. (DOCX 15 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, D., Dong, T., Shao, Y. et al. Laparoscopy versus open appendectomy for elderly patients, a meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Surg 19, 54 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-019-0515-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-019-0515-7