Abstract

Background

The study aimed to evaluate the combined effect of Pulsed Electromagnetic Field (PEMF) biophysical stimulation and bone marrow concentrate (BMC) in osteochondral defect healing in comparison to the treatment with scaffold alone.

Methods

An osteochondral lesion of both knees was performed in ten rabbits. One was treated with a collagen scaffold alone and the other with scaffold seeded with BMC. Half of the animals were stimulated by PEMFs (75 Hz, 1.5 mT, 4 h/day) and at 40 d, macroscopic, histological and histomorphometric analyses were performed to evaluate osteochondral defect regeneration.

Results

Regarding cartilage, the addition of BMC to the scaffold improved cell parameters and the PEMF stimulation improved both cell and matrix parameters compared with scaffold alone. The combination of BMC and PEMFs further improved osteochondral regeneration: there was an improvement in macroscopic, cartilage cellularity and matrix parameters and a reduction in the percentage of cartilage under the tidemark. Epiphyseal bone healing improved in all the osteochondral defects regardless of treatment, although PEMFs alone did not significantly improve the reconstruction of subchondral bone in comparison to treatment with scaffold alone.

Conclusions

Results show that BMC and PEMFs might have a separate effect on osteochondral regeneration, but it seems that they have a greater effect when used together. Biophysical stimulation is a non-invasive therapy, free from side effects and should be started soon after BMC transplantation to increase the quality of the regenerated tissue. However, because this is the first explorative study on the combination of a biological and a biophysical treatment for osteochondral regeneration, future preclinical and clinical research should be focused on this topic to explore mechanisms of action and the correct clinical translation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Regenerative therapy for osteochondral lesions aims to produce a durable cartilage-like and bone tissues with the same structure and function as the native cartilage and well integrated with the surrounding tissues [1]. However, until now, the traditional surgical strategies have not been able to repair completely osteochondral lesions, but often produce a fibrous or fibrocartilaginous tissue that undergoes degeneration in the long term, with reduced biological, biomechanical and biochemical features [2].

Recently, tissue engineering (TE) approaches have emerged in the scenario of orthopedics as a promising alternative to overcome the limitations of traditional surgery [3]. Among the different scaffolds, collagen-based ones provide a natural cartilage and bone microenvironment, which promote mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) or chondrocyte attachment, proliferation, activity and extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition [4].

A one-step TE procedure, based on the use of bone marrow concentrate (BMC) transplantation, has gained popularity because it overcomes the limits and risks of the in vitro MSC expansion procedures (long times, costs, cell transformation, contamination and unnatural differentiation), usually performed to obtain a useful amount of cells for scaffold colonization. BM cells can be harvested easily from the patient’s iliac crest, concentrated directly in the operating theatre and implanted arthroscopically once seeded onto a scaffold, thus avoiding the need for two surgical stages (one for cell harvesting and another for implantation) [4]. In addition, autologous BMC carries also accessory cells and several growth factors that induce angiogenesis and vasculogenesis [5].

Hyaluronic acid and collagen have been used for osteochondral regeneration in combination with BMC for the regeneration of osteochondral lesions in patients. Good results have been obtained independently of the scaffold used in some cases [5, 6], whereas better results have been reported with a collagen scaffold compared to a hyaluronic acid membrane in others [7].

There is an increasing awareness of the importance of the microenvironment where both scaffolds and cells are transplanted. The inflammatory joint microenvironment, produced by the lesion itself or subsequent to the surgical procedure, should be considered as an important variable that causes MSC differentiation towards a fibroblastic phenotype and might also affect scaffold degradation [8]. The rationale for using Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields (PEMFs) in association with TE strategies was recently supported by evidence of both an anabolic effect on implanted cells and surrounding tissues and an anti-inflammatory effect protecting cells from the catabolic effects of inflammation [8]. Besides improvements in cartilaginous tissue healing [8, 9], it has been observed that biophysical stimulation with PEMFs, promotes osteochondral graft healing and integration [10, 11]. Boopalan et al., showed the effectiveness of PEMF stimulation in hyaline cartilage formation six weeks after the implantation of a calcium phosphate scaffold in ostechondral defects in rabbits [12].

Therefore, the hypothesis of the present in vivo study was that the combination of PEMF stimulation and the seeding of BMCs onto a collagenous scaffold might have a potential additive or synergic therapeutic effect in enhancing osteochondral regeneration in comparison to scaffold alone.

We evaluated the regenerative potential through macroscopic, histological and histomorphometric analyses in a rabbit model of osteochondral defect.

Methods

The study was performed according to European and Italian legislation on animal experimentation (Law by Decree No.116/92). The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Rizzoli Orthopaedic Institute and Italian Ministry of Health. Ten adult male New Zealand rabbits (about 5 months old, 3.0 ± 0.3 kg) (HARLAN Laboratories SRL, Udine-Italy) were housed under controlled conditions and supplied with standard diets. General anaesthesia was induced with an intramuscular injection of 44 mg/kg ketamine (Imalgene 1000, Merial Italia SPA, Padova-Italy) and 3 mg/kg xylazine (Rompum, Bayer Italia SpA, Milan-Italy) and maintained with O2 and air (0.5 l/min) mixed with 2-3 % Isofluoran (Aerrane, Baxter S.p.A, Rome-Italy) in spontaneous ventilation.

BMC isolation

Before joint surgery, 6.0 ± 1.5 ml of BM from the posterior iliac crest of each animal was aspirated into a syringe coated with saline-heparin solution and the needle was rotated to prevent venous return. The samples were immediately sent to the laboratory and an equal volume of physiological solution (Fresenius Kabi Italia s.r.l., Verona-Italy) was added to the BM aspirate, then stratified on Ficoll-Paque (density 1.083 g/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan-Italy) and subsequently centrifuged at 600 g for 30 min. The low-density cellular layer was separated, counted and resuspended in 200 μl of physiological solution for immediate surgical implantation.

Joint surgery

Through a lateral knee arthrotomy, an osteochondral defect of 4 × 4 mm was performed in the loading area of both medial femoral condyles with a dimension comparable to that of a clinical microfracture [13]. In each animal, one defect was filled with a scaffold (BIOPAD, Novagenit, Trento-Italy) consisting of heterologous equine type I collagen, and the other one with the scaffold seeded with BMC (2.03 × 106 BM mononuclear cells). The joint capsule and skin were sutured and after surgery the animals received antibiotics, 30 mg/Kg of Flumequine (Flumexil, Fatro SpA, Bologna-Italy) for 4 d and analgesics, 80 mg/Kg of sodium metamizole (Farmolisina, Ceva SpA, Monza-Italy).

From the first post-operative day, half of the animals underwent biophysical PEMF stimulation with 1.5 mT, 75 Hz (I-ONE, Igea SpA, Modena-Italy) 4 h/day until the end of the experimental time. Two solenoids, positioned at the level of articulations, were placed outside Plexiglas cages and connected to a pulsed generator. The same conditions were maintained also in the other half of the animals, but without the activation of the generator (not stimulated animals).

After 40 d, under general anaesthesia, the animals were pharmacologically euthanized with intravenous injection of 1 ml Tanax (Hoechst AG, Frankfurt-am-Mein-Germany).

Four groups of five treated knees were examined: Group 1 (scaffold), Group 2 (scaffold seeded with BMC), Group 3 (scaffold and PEMFs), and Group 4 (scaffold seeded with BMC and PEMFs).

Post-surgical evaluations

The Niederauer score was used for gross morphological evaluation [14].

Both condyles of all animals were processed and sectioned as in a previous study [15]. For each sample three consecutive central sections of the entire volume of the lesion were stained with Safranin-O/Fast Green. Histological analysis was performed by a light optical microscope (Olympus-BX51, Italia Srl, Milan-Italy), equipped with a camera and connected to an imaging analysis system (Leica QWIN, Leica Microsystems Srl, Milan-Italy). A semi-quantitative O’Driscoll modified grading score [16] was used to evaluate both cartilage and bone compartments by two blinded investigators (Table 1).

The amount of new cartilaginous tissue, over and under the tidemark, was calculated in a region of interest (ROI) inside the osteochondral defect [17]. The percentage (%) of new cartilage, obtained by binarizing the area of positive Safranin-O staining, was calculated as (new cartilage area/ROI area) × 100.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics v.21 software. After checking the normal distribution and the homogeneity of the variance, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to verify if there were significant differences in the macroscopic and histomorphometric results among groups. Then, the Mann–Whitney U test was evaluated by the Monte Carlo method to compute two-sided probability to compare the results of Group 2, Group 3 and Group 4 with Group 1.

Results

Macroscopic evaluations

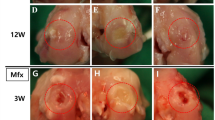

No surgical or post-operative complications were observed and the animals tolerated both surgery and PEMF stimulation well. The Group 1 defects were partially empty with a rough brown fibrous tissue surface and a slight depression in the center and those of Group 2 appeared translucent with a high degree of filling and integration. In both cases the margins of the lesion were almost indistinguishable. Group 3 presented irregularities in the well-integrated and barely noticeable surface that was approximately filled up to the level of adjacent cartilage and those of Group 4 were filled with a fully-integrated and transparent cartilage-like tissue, quite indistinguishable from normal adjacent tissue.

The total and subcategories Niederauer score showed significantly higher values in Group 4 in comparison with Group 1 (p < 0.05), except for the surface smoothness parameter (Fig. 1).

Histological and histomorphometric evaluations

Forty days after surgery, the scaffold was no longer recognizable in any of the Groups and no inflammatory cells or fibrous capsules were found regardless of treatment.

The Group 1 defects were characterized by the presence of a fibrocartilage, with a poor glycosaminoglycan (GAG) staining, an altered distribution of chondrocytes, grouped in clusters, and zones of hypocellularity (Fig. 2a). Group 2 showed a fibrocartilage with a normal cell distribution, few clusters and slight hypocellularity (Fig. 2b). After PEMF stimulation, the repaired tissue of Group 3 was a mix of hyaline cartilage and fibrocartilage with moderate matrix staining, slight fibrillation and some clusters of chondrocytes in a few zones (Fig. 2c). Group 4 defects presented mainly hyaline cartilage, with a normal GAG content, nearly smooth surface, no clusters, no hypocellularity and cells with a columnar aspect (Fig. 2d). In all Groups, both edges were integrated with the adjacent cartilage, which appeared normal with no signs of degeneration. In Group 4 bone reconstruction was complete.

Table 2 and Fig. 3 show the modified O’Driscoll score results.

Considering the effect of BMC, the total modified O’Driscoll score was significantly higher in Group 2 than in Group 1 (p < 0.05), with an improvement in hypocellularity (p < 0.005), cell distribution (p < 0.05), bone infiltration (p < 0.005) and the other bone parameters (p < 0.05).

Regarding PEMF effect, the total modified O’Driscoll score was significantly higher in Group 3 than in Group 1 (p < 0.05), with low hypocellularity (p < 0.005) and better tissue morphology (p < 0.05) and bone microarchitecture parameters (p < 0.005), except for the reconstruction of bone parameters.

Group 4 showed a significantly higher modified O’ Driscoll score (p < 0.05) than Group 1, concerning matrix staining, neocartilage alignment (p < 0.05), hypocellularity and cell distribution (p < 0.005) and bone parameters (p < 0.005).

Finally, the percentage of cartilage under the tidemark was significantly lower in Group 4 than in Group 1 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Discussion

This study evaluated the separate and combined effect of BMC implantation and PEMF stimulation on osteochondral healing potential of collagenous scaffold alone.

Besides cartilage, the bone compartment was also assessed because proper bone healing influences the long-term articular cartilage repair, with high quality and smoother surface, gives mechanical support for both cartilage formation and lateral integration and protects cartilage from loss and stresses [18].

Seeding BMC on the scaffold improved the cartilage cellularity parameters of the modified O’Driscoll score, because BM cells are able to undergo a chondrogenic differentiation once implanted in the joint microenvironment and influence the microenvironment through a paracrine effect. Similar results were also observed in previous studies where enhanced healing of equine and mini-pig osteochondral defects was obtained with BMC [19, 20].

PEMF stimulation significantly improved not only cartilage cellularity, but also the neo-tissue morphology, whereas the combination of PEMFs and BMC improved their separate effects: macroscopic appearance, cellularity, neo-tissue staining and alignment were significantly better and the amount of cartilage under the tidemark was significantly reduced when PEMFs were combined with BMC in comparison to scaffold alone. The amount of cartilage under the tidemark is an index of subchondral bone regeneration, because the less the subchondral bone defect is filled by cartilage or fibrous tissue, the more it is filled by bone [17]. The histological parameters of bone improved, regardless of treatments, even if only the reconstruction of subchondral bone in Group 3 was similar to that of Group 1. In agreement with literature data [18], in this study the improvement of bone was associated not only with a better trabecular bone architecture, but also an improvement in cartilage cellularity, structure, alignment and ECM component synthesis, thus confirming that a proper bone regeneration contributes to a better cartilage repair.

It is also important to underline that lateral integration of neocartilage and attachment to the underlying bone occurred in all the treated groups.

In the current study a scaffold already used with good results in clinical practice was implanted, to measure the effect of BMC and PEMFs and to avoid the variability of innovative scaffolds and to easily translate our research results to patients. Forty days after surgery, the scaffold was no longer present in any treatment group but was replaced by more or less mature cartilage and bone tissues.

In the treatment of osteochondral defects several studies have evaluated separately the biophysical stimulation [10, 12] and BMC implantation technique [4, 19, 20] but to our knowledge, there is a lack of preclinical data on the combined effects of the cell therapy and PEMFs on osteochondral defect regeneration. In addition, a previous in vitro study by Wang Q et al. also underlined the effects of PEMF on MSC osteogenic differentiation as a new TE technique to be employed before the in vivo use of MSC for bone regeneration [21]. The authors observed the osteogenic differentiation of amniotic epithelial cells, as the MSC source, thus showing that the combination of PEMF stimulation and osteoinductive medium improved cell osteogenic differentiation in comparison to their use separately [21]. In the scope of a larger project it was recently shown by Cadossi et al. that PEMF stimulation improved recovery, pain control and clinical outcome in patients treated with collagen scaffold combined with BMC in osteochondral lesions of the talus after 60 d of treatment [22]. The present in vivo data strongly support the first clinical evidence with the help of histological and histomorphometric analyses, but the short-term follow-up and the single experimental time do not allow further maturation or gradual deterioration of the regenerated tissues to be observed. In addition, a mechanistic explanation of the PEMF effects has to be explored in other specific studies with an appropriate set-up.

Conclusions

The results suggest that a TE approach, represented by BMC seeding on a collagen scaffold, combined with low-frequency PEMF stimulation, rather than separately, improves osteochondral regeneration, thus confirming the hypothesis of the study. Even if all treatments significantly enhanced bone architecture, only the combined use of BMC and PEMF stimulation improved cartilage cellularity and matrix GAG content, the macroscopic appearance and the percentage of cartilage under the tidemark. Biophysical stimulation is a non-invasive therapy, free from side effects and should be started soon after BMC transplantation to increase the quality of the regenerated tissue. However, because this is the first explorative study on the combination of a biological and a biophysical treatment for osteochondral regeneration, future preclinical and clinical research should focus on this topic to explore mechanisms of action and the correct clinical translation.

Abbreviations

- TE:

-

Tissue engineering

- MSC:

-

Mesenchymal stem cell

- ECM:

-

Extracellular matrix

- BMC:

-

Bone marrow concentrate

- PEMFs:

-

Pulsed electromagnetic fields

- ROI:

-

Region of interest

- GAG:

-

Glycosaminoglycan.

References

Redman SN, Oldfield SF, Archer CW. Current strategies for articular cartilage repair. Eur Cell Mater. 2005;9:23–32.

Becerra J, Andrades JA, Guerado E, Zamora-Navas P, López-Puertas JM, Reddi AH. Articular cartilage: structure and regeneration. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2010;16(6):617–27. doi:10.1089/ten.TEB.2010.0191.

Gikas PD, Bayliss L, Bentley G, Briggs TW. An overview of autologous chondrocyte implantation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(8):997–1006. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.91B8.21824.

Veronesi F, Giavaresi G, Tschon M, Borsari V, Nicoli Aldini N, Fini M. Clinical use of bone marrow, bone marrow concentrate, and expanded bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in cartilage disease. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22(2):181–92. doi:10.1089/scd.2012.0373.

Buda R, Vannini F, Cavallo M, Baldassarri M, Natali S, Castagnini F, et al. One-step bone marrow derived cell transplantation in talarosteochondral lesions: mid-term results. Joints. 2014;1(3):102–7.

Buda R, Vannini F, Castagnini F, Cavallo M, Ruffilli A, Ramponi L, et al. Regenerative treatment in osteochondral lesions of the talus: autologous chondrocyte implantation versus one step bone marrow derived cells transplantation. 2015; Int Orthop [Epub ahead of print].

Cavallo M, Buda R, Vannini F, Castagnini F, Ruffilli A, Giannini S. Subchondral bone regenerative effect of two different biomaterials in the same patients. Case Rep Orthop. 2013:850502. doi:10.1155/2013/850502.

Fini M, Pagani S, Giavaresi G, De Mattei M, Ongaro A, Varani K, et al. Functional tissue engineering in articular cartilage repair: is there a role for electromagnetic biophysical stimulation? Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2013;19(4):353–67. doi:10.1089/ten.TEB.2012.0501.

Vincenzi F, Targa M, Corciuolo C, Gessi S, Merighi S, Setti S, et al. Pulsed electromagnetic fields increased the anti-inflammatory effect of A2A and A3 adenosine receptors in human T/C-28a2 chondrocytes and hFOB 1.19 osteoblasts. Plos One. 2013;8(5), e65561. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065561.

Benazzo F, Cadossi M, Cavani F, Fini M, Giavaresi G, Setti S, et al. Cartilage repair with osteochondral autografts in sheep: effect of biophysical stimulation with pulsed electromagnetic fields. J Orthop Res. 2008;26(5):631–42. doi:10.1002/jor.20530.

van Bergen CJ, Blankevoort L, de Haan RJ, Sierevelt IN, Meuffels DE, d'Hooghe PR, et al. Pulsed electromagnetic fields after arthroscopic treatment for osteochondral defects of the talus: double-blind randomized controlled multicenter trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:83. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-10-83.

Boopalan PR, Arumugam S, Livingston A, Mohanty M, Chittaranjan S. Pulsed electromagnetic field therapy results in healing of full thickness articular cartilage defect. Int Orthop. 2011;35(1):143–8. doi:10.1007/s00264-010-0994-8.

Goyal D, Keyhani S, Lee EH, Hui JH. Evidence-based status of microfracture technique: a systematic review of level I and II studies. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(9):1579–88. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2013.05.027.

Niederauer GG, Slivka MA, Leatherbury NC, Korvick DL, Harroff HH, Ehler WC, et al. Evaluation of multiphase implants for repair of focal osteochondral defects in goats. Biomaterials. 2000;21(24):2561–74.

Veronesi F, Giavaresi G, Guarino V, Raucci MG, Sandri M, Tampieri A, et al. Bioactivity and bone healing properties of biomimetic porous composite scaffold: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2015 Feb 17. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.35433. [Epub ahead of print].

Olivos-Meza A, Fitzsimmons JS, Casper ME, Chen Q, An KN, Ruesink TJ, et al. Pretreatment of periosteum with TGF-b1 in situ enhances the quality of osteochondral tissue regenerated from transplanted periosteal grafts in adult rabbits. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(9):1183–91. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2010.06.003.

Jiang Y, Chen LK, Zhu DC, Zhang GR, Guo C, Qi YY, et al. The inductive effect of bone morphogenetic protein-4 on chondral-lineage differentiation and in situ cartilage repair. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16(5):1621–32. doi:10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0681.

Fortier LA, Potter HG, Rickely EJ, Schnabel LV, Foo LF, Chong LR, et al. Concentrated bone marrow aspirate improves full-thickness cartilage repair compared with microfracture in the equine model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(10):1927–37. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.01284.

Betsch M, Thelen S, Santak L, Herten M, Jungbluth P, Miersch D, et al. The role of erythropoietin and bone marrow concentrate in the treatment of osteochondral defects in mini-pigs. PLoS One. 2014;9(3), e92766. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092766.

Betsch M, Schneppendahl J, Thuns S, Herten M, Sager M, Jungbluth P, et al. Bone marrow aspiration concentrate and platelet rich plasma for osteochondral repair in a porcine osteochondral defect model. PLoS One. 2013;8(8), e71602. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0071602.

Wang Q, Wu W, Han X, Zheng A, Lei S, Wu J, et al. Osteogenic differentiation of amniotic epithelial cells: synergism of pulsed electromagnetic field and biochemical stimuli. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:271. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-271.

Cadossi M, Buda RE, Ramponi L, Sambri A, Natali S, Giannini S. Bone marrow-derived cells and biophysical stimulation for talar osteochondral lesions: a randomized controlled study. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35(10):981–7. doi:10.1177/1071100714539660.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by Rizzoli Orthopedic Institute “5 × mille” 2010, “PRRIITT-Programma regionale per la ricerca industriale, l’innovazione e il trasferimento tecnologico” 2008 and Regione Emilia-Romagna Programma di Ricerca Regione Università 2010–2012 "Regenerative Medicine of Cartilage and Bone" projects.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Stefania Setti is employed in IGEA, that developed the PEMF generator.

Authors’ contributions

FV has made substantial contributions to acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, has been involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved; MC has made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data; GG has made substantial contributions to acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and has been involved in drafting the manuscript; LM has made substantial contributions to acquisition of data; SS has been involved in drafting the manuscript; RB has made substantial contributions to the design and interpretation of data; SG has made substantial contributions to conception and has been involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; MF has been made substantial contributions to conception and design, has been involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, has given final approval of the version to be published and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Veronesi, F., Cadossi, M., Giavaresi, G. et al. Pulsed electromagnetic fields combined with a collagenous scaffold and bone marrow concentrate enhance osteochondral regeneration: an in vivo study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 16, 233 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0683-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0683-2