Abstract

Background

Data on changes in lung function in eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are limited. We investigated the longitudinal changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and effects of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) in Korean COPD patients.

Methods

Stable COPD patients in the Korean COPD subgroup study (KOCOSS) cohort, aged 40 years or older, were included and classified as eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic COPD based on blood counts of eosinophils (greater or lesser than 300 cells/μL). FEV1 changes were analyzed over a 3-year follow-up period.

Results

Of 627 patients who underwent spirometry at least twice during the follow up, 150 and 477 patients were classified as eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic, respectively. ICS-containing inhalers were prescribed to 40% of the patients in each group. Exacerbations were more frequent in the eosinophilic group (adjusted odds ratio: 1.49; 95% confidence interval: 1.10–2.03). An accelerated FEV1 decline was observed in the non-eosinophilic group (adjusted annual rate of FEV1 change: − 12.2 mL/y and − 19.4 mL/y for eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic groups, respectively). In eosinophilic COPD, the adjusted rate of annual FEV1 decline was not significant regardless of ICS therapy, but the decline rate was greater in ICS users (− 19.2 mL/y and − 4.5 mL/y, with and without ICS therapy, respectively).

Conclusions

The annual rate of decline in FEV1 was favorable in eosinophilic COPD compared to non-eosinophilic COPD, and ICS therapy had no beneficial effects on changes in FEV1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive inflammatory airway disease characterized by reduced airflow, and is a leading cause of mortality worldwide [1].

COPD is regarded as heterogeneous condition and chronic airway inflammation in COPD is thought to be driven by neutrophils and lymphocytes [2]. This type of airway inflammation is a prominent feature in most COPD patients unlike in asthmatic patients, and related to the degree of airflow limitation [3].

Airway inflammation in asthma is mediated by type-2 T helper (Th2) cells and eosinophils, associated with an exacerbation risk and poor disease control following inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) withdrawal [4, 5]. The presence of eosinophils has been reported in the blood or sputum of 30–40% COPD patients [6]. Excluding patients with clinical features suggestive of asthma, such as bronchial hyperresponsiveness, history of asthma, atopy, and reversible airflow limitation, a subset of COPD patients demonstrates eosinophilic airway inflammation and responds to corticosteroid therapy [7,8,9].

Several studies have reported a greater risk for COPD exacerbation with higher blood counts of eosinophils, although the relationship remains controversial. In the general population, spirometry-based COPD patients experience more exacerbations with high blood eosinophil counts [10, 11]. Although higher eosinophil levels increase the risk for COPD exacerbation, they are also associated with a greater risk reduction after the use of ICS [12,13,14].

However, few studies have investigated the effects of blood levels of eosinophils on lung function. In this study, we evaluated longitudinal changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) in patients with eosinophilic COPD, and analyzed the effects of ICS on this parameter.

Methods

Study population

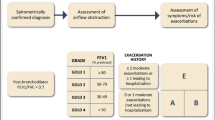

Data were obtained from the Korean COPD Subgroup Study (KOCOSS; 2012–2019), an ongoing prospective multicenter observational cohort, which has recruited COPD patients from 48 referral hospitals in the Republic of Korea [15]. The inclusion criteria were (1) age ≥ 40 years; and (2) COPD diagnosed by pulmonologists based on respiratory symptoms and spirometry-confirmed fixed airflow limitation (post-bronchodilator FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) < 0.70). Only patients with blood eosinophil count data at baseline enrollment during stable state and followed up at least 3 years from enrollment were included in the analyses.

Clinical data

KOCOSS cohort contained detailed information regarding sociodemographics (including age, sex, smoking history, and education level), symptoms (chronic cough or persistent phlegm ˃ 3 months), dyspnea severity based on the Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale (mMRC), and quality of life based on the COPD assessment test (CAT) and the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ). Data on comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, tuberculosis, and asthma, were also collected. The treatment of the subjects depended on their attending pulmonologist.

The KOCOSS cohort patients were followed-up at least every 6 months, and moderate and severe exacerbations were recorded at each visit. Moderate exacerbation was defined as an exacerbation leading to an outpatient-clinic visit earlier than scheduled and prescribed systemic steroids and/or antibiotics, whereas severe exacerbation was defined as leading to an emergency department visit or hospitalization.

Pulmonary function test

Spirometry was performed based on American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society guidelines [16]. Absolute FEV1 values were obtained, and the predicted percentage values (% pred) for FEV1 were calculated using an equation developed for the Korean population [17]. Positive bronchodilator response (BDR) was defined as post-bronchodilator FEV1 increase in 12% or more, and 200 mL from baseline. Subjects were followed-up at least every 6 months, and spirometry was performed annually.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were expressed as means ± standard deviations and absolute numbers with percentages. Continuous and categorical variables were compared using t-test and chi-square test, respectively.

In this study, we assess the longitudinal changes in post-bronchodilator FEV1 (mL). To exclude the immediate effects of bronchodilator treatment, lung function data used for longitudinal analysis were collected one year after enrollment.

Although variability on serial blood eosinophil counts may be concernable, over 300 cells/µL is regarded as threshold for predicting increased risk of exacerbation and high likelihood of benefit with ICS [18, 19]. We compared the longitudinal FEV1 change between eosinophilic (blood eosinophil count ≥ 300 cells/μL) and non-eosinophilic (blood eosinophil count < 300 cells/μL) COPD, using a linear mixed-effects model with random intercepts and slopes. We analyzed mean annual rates of FEV1 change based on multiple covariates: age, sex, smoking (pack-years), and body mass index (BMI). Then, we analyzed FEV1 changes based on ICS usage.

All tests were two-sided and a p-value less than.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata (v. 16; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Study subjects

A total of 2,181 COPD patients were enrolled between January 2012 and December 2019. FEV1 change analysis based on blood counts of eosinophils was available for 627 patients (Fig. 1). Comparison of clinical features between eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic COPD is shown in Table 1. Eosinophilic COPD was more prevalent in males (98.7% and 91.2%, for eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic groups, respectively). There were no significant differences in age, smoking status, symptoms, and quality of life. Past exacerbations were more common in eosinophilic COPD group, compared to non-eaosinophilic group (25.3% and 18.5%, respectively), but the difference was not statistically significant.

Baseline pulmonary function test results are shown in Table 2. More than 60% of the patients in both groups were GOLD stage 1 or 2 (FEV1 ≥ 50% of predicted value), and there were no significant differences in the severity of airflow limitation and exercise capacity. Mean blood counts of eosinophils were higher in the eosinophilic COPD group (546.1 vs. 141.8 cells/μL).

ICS therapy, either alone or in combination with long-acting β2-agonists (LABA) and/or long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA), was prescribed in 41.1% and 40.7% in non-eosinophilic and eosinophilic groups, respectively.

Exacerbation risk

Exacerbations were identified in 414 of the 627 patients. Moderate to severe exacerbations occurred in 71.0% of the patients (294/414), and 20.8% of the patients (86/414) experienced frequent exacerbations (≥ 2 events/year).

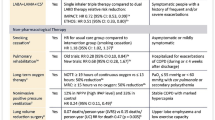

Exacerbations were occurred in 76.6% (82/107) of eosinophilic COPD group, while in 69.1% (212/307) of non-eosinophilic group. The exacerbation risk was significantly higher in the eosinophilic group compared to the non-eosinophilic group (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 1.49; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.10–2.03; p < 0.05). However, the statistical significance was lost with adding ICS therapy as covariate (aOR: 1.63; 95% CI: 0.89–2.99) (Table 3).

Longitudinal FEV 1 change

A greater FEV1 decline rate was observed in the non-eosinophilic group, compared to the eosinophilic group (− 19.6 mL/y and − 12.9 mL/y, respectively) (Fig. 2). The adjusted annual FEV1 declined significantly in the non-eosinophilic COPD group (− 19.4 mL/y). Although the adjusted annual FEV1 also decreased in the eosinophilic COPD group, the rate of decline was not significant (− 12.2 mL/y) (Table 4). In the eosinophilic COPD group, the adjusted annual FEV1 decline rate was not significant regardless of ICS therapy, but the decline rate was greater in ICS users (− 19.2 mL/y and − 4.5 mL/y, with and without ICS therapy, respectively) (Table 5). The exact values of FEV1 changes during two years of follow-up between eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic COPD are shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Discussion

There is limited data regarding the effects of ICS on FEV1 change in COPD. We hypothesized that the rate of FEV1 change differed based on the baseline blood eosinophil counts and ICS therapy. The adjusted annual rate of FEV1 change declined significantly in the low-blood-eosinophil group, compared to the high-blood-eosinophil group, although the difference was not statistically significant. Analyses of ICS effects on FEV1 change in high-blood eosinophil group showed no statistically significant differences.

It is widely accepted that COPD develops because of a genetic susceptibility for progressive airway inflammation, triggered by complex environmental factors over time, such as smoking, pollutants, and allergens, which leads to irreversible damage and airflow obstruction [3, 20]. Typically, airways of COPD patients exhibit increased CD8 + T cells and neutrophils. Although Th2 inflammatory pathway is considered a feature of asthma rather than COPD, 30–40% of COPD patients demonstrated eosinophilic-inflammation [6]. These heterogeneity of disease are now accepted as various clinical phenotypes with different pathophysiologies and endotypes. Therefore, response to therapies might also be variable. The ECLIPSE (Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate End points) cohort study reported that 37.4% of COPD patients had persistently high (≥ 2%), 13.6% had persistently low (< 2%), and 49% had variable eosinophil counts over a 3-year follow-up period [6]. A subset of COPD patients demonstrate eosinophilic inflammation either in stable period or during acute exacerbations. Blood eosinophilia was associated with increased exacerbation risk, and this phenotype could benefit from corticosteroid therapy directed against eosinophilic inflammation [13, 14, 21,22,23]. A recent trial targeted eosinophilic inflammation (IL-5) to reduce exacerbation risk in eosinophilic COPD patients, suggesting that selectively eosinophilic-pathway blockers may be effective for such patients [24]. Elevated peripheral blood eosinophil counts in COPD may be used to identify patients who are expected to have favorable response to ICS therapy or biologics targeting Th2 inflammatory pathway. Conversely, ICS withdrawal in eosinophilic COPD leads to increases exacerbation risk [25]. Following ICS withdrawal, trough FEV1 decreased and exacerbation risk increased only in the high eosinophil group [26].

Most trials assess the impact of ICS on COPD using exacerbation risk as the outcome, therefore data regarding ICS effects on FEV1 change is limited. A post hoc study reported favorable effects of extrafine beclomethasone dipropionate and formoterol fumarate, compared to formoterol fumarate alone, on FEV1 change in the highest blood eosinophil quartile (≥ 279.8 cells/μL). In this trial, severe COPD patients with FEV1 of 30–50% of predicted value, and at least one exacerbation in the previous year were included [27].

A study on effects of ICS monotherapy on disease progression in moderate to severe COPD reported no differences in the rate of decline of post-bronchodilator FEV1 between fluticasone propionate and placebo over 3 years. However, when analyzed using baseline blood eosinophil levels, the rate of FEV1 decline was significantly lower in the fluticasone propionate group compared to placebo in the ≥ 2% eosinophil group (− 40.6 mL/y and − 74.5 mL/y, respectively; p = 0.003)[22].

In the present study, annual rate of FEV1 change declined significantly in the lower blood eosinophil group. Analyses of ICS effects on longitudinal FEV1 change in high-blood-eosinophil group revealed a greater decline rate in ICS users. Although we demonstrated increased exacerbation risk in the eosinophilic COPD group, consistent with previous studies [10,11,12], the annual FEV1 decline rate was low in eosinophilic COPD compared to non-eosinophilic COPD, and ICS provided no benefits. Unlike previous trials [22, 27], only 20% of subjects had previous exacerbations and approximately 66% had mild to moderate FEV1 severities in the KOCOSS cohort. Different airflow obstruction severities and previous exacerbation history may have caused the differences in FEV1 change.

In this study, we used blood eosinophil count as a marker of treatment response to ICS in COPD cohort. In consideration of patients with asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) high probability, we defined ACO by eosinophil count of cells/μL and/or extreme BDR criteria (> 15% and 400 mL). More than 98% were classified according to the eosinophil criteria. Absence of unified diagnostic criteria for ACO resulted in inconsistent clinical manifestations and outcomes. Moreover, in our previous study, we showed that blood eosinophil was the single most important biomarker to predict the decrease of exacerbation by ICS [28]. Recently, interests in precision medicine according to the subtype of COPD, rather than ACO is increasing. Blood eosinophil count is considered as the reliable biomarker in identifying subtype that might be benefitted by ICS. Although we did not find meaningful relation between FEV1 change and ICS use in eosinophilic COPD in real world data, additional prospective studies will be needed.

There were several limitations in this study. First, we analyzed subsequent 2 years of FEV1 data, which is a relatively short follow-up period. Second, we defined eosinophilic COPD using blood eosinophil counts at a stable period, and variation over time were not reflected. Third, COPD patients in our study were enrolled irrespective of treatment- naïve status. Whether blood eosinophil count less than or over 300cell/μL, the prescription rate for ICS containing inhalers was similar, which implies considerable numbers of subjects who have already been exposed to ICS are included, and this might be related to attenuation of ICS effects on eosinophilic COPD. Fourth, this was not a randomized clinical trial. Although the prescription rate for ICS containing inhalers was similar in both groups (41.1% and 40.7% in non-eosinophilic and eosinophilic groups, respectively.), ICS containing inhalers was not randomly assigned. ICS prescription was decided by pulmonologists. Thus, there can be a bias for the prescription of ICS. Caution is needed to interpret the impact of ICS on eosinophilic COPD. Fifth, changes in FEV1 according to GOLD classification could not be performed because approximately 90% of subjects were in GOLD group A or B. Lastly, we aimed to assess the rate of decline of FEV1 according to blood eosinophil count and whether FEV1 decline differs between eosinophilic COPD with and without ICS. Whittaker et al. [29] reported ICS use is associated with slower rates of FEV1 decline in COPD regardless of blood eosinophil level in a cohort of 26,675 COPD patients. On the other hand, Celli et al. [30] reported ICS plus LABA combination or the component, reduces the rate of decline of FEV1 in moderate to severe COPD. This study included more than 1,000 patients in each of subgroups. However, our study is underpowered to address intended questions about rate of decline of FEV1 due to small number of subjects.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that the favorable longitudinal FEV1 change in eosinophilic COPD patients compared to non-eosinophilic COPD over 3 years in a Korean COPD cohort. ICS use did not have any beneficial effects on FEV1 change in eosinophilic COPD, but FEV1 decreased more rapidly with ICS use. Further studies with longer follow-up periods in larger number of patients are required.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Requests to obtain the raw data used for this study should be directed to the corresponding author, Chin Kook Rhee, at chinkook77@gmail.com.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Acute exacerbation

- ATS:

-

American Thoracic Society

- BDR:

-

Bronchodilator response

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CAT:

-

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Assessment Test

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DLCO:

-

Diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide

- FEV1 :

-

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- GOLD:

-

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

- ICS:

-

Inhaled corticosteroid

- LABA:

-

Long acting beta2 receptor agonist

- LAMA:

-

Long acting muscarinic receptor agonist

- mMRC:

-

Modified Medical Research Council

- PDE4 inhibitor:

-

Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor

- PY:

-

Pack-year

- SGRQ:

-

St. George's Respiratory Disease Questionnaire

- 6MWD:

-

6-Min walk distance

References

Mannino DM, Braman S. The epidemiology and economics of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4(7):502–6.

O’Donnell R, Breen D, Wilson S, Djukanovic R. Inflammatory cells in the airways in COPD. Thorax. 2006;61(5):448–54.

Di Stefano A, Capelli A, Lusuardi M, Balbo P, Vecchio C, Maestrelli P, et al. Severity of airflow limitation is associated with severity of airway inflammation in smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(4):1277–85.

Barnes PJ. Immunology of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(3):183–92.

Aleman F, Lim HF, Nair P. Eosinophilic endotype of asthma. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2016;36(3):559–68.

Singh D, Kolsum U, Brightling CE, Locantore N, Agusti A, Tal-Singer R. Eosinophilic inflammation in COPD: prevalence and clinical characteristics. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1697–700.

Brightling CE, McKenna S, Hargadon B, Birring S, Green R, Siva R, et al. Sputum eosinophilia and the short term response to inhaled mometasone in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005;60(3):193–8.

Brightling CE, Monteiro W, Ward R, Parker D, Morgan MD, Wardlaw AJ, et al. Sputum eosinophilia and short-term response to prednisolone in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356(9240):1480–5.

Leigh R, Pizzichini MM, Morris MM, Maltais F, Hargreave FE, Pizzichini E. Stable COPD: predicting benefit from high-dose inhaled corticosteroid treatment. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(5):964–71.

Vedel-Krogh S, Nielsen SF, Lange P, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG. Blood eosinophils and exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Copenhagen General Population Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(9):965–74.

Zeiger RS, Tran TN, Butler RK, Schatz M, Li Q, Khatry DB, et al. Relationship of blood eosinophil count to exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(3):944-54.e5.

Pascoe S, Locantore N, Dransfield MT, Barnes NC, Pavord ID. Blood eosinophil counts, exacerbations, and response to the addition of inhaled fluticasone furoate to vilanterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a secondary analysis of data from two parallel randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(6):435–42.

Papi A, Vestbo J, Fabbri L, Corradi M, Prunier H, Cohuet G, et al. Extrafine inhaled triple therapy versus dual bronchodilator therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRIBUTE): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1076–84.

Pascoe S, Barnes N, Brusselle G, Compton C, Criner GJ, Dransfield MT, et al. Blood eosinophils and treatment response with triple and dual combination therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: analysis of the IMPACT trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(9):745–56.

Lee JY, Chon GR, Rhee CK, Kim DK, Yoon HK, Lee JH, et al. Characteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at the first visit to a pulmonary medical center in Korea: The KOrea COpd Subgroup Study Team Cohort. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(4):553–60.

Wanger J, Clausen JL, Coates A, Pedersen OF, Brusasco V, Burgos F, et al. Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(3):511–22.

Choi JK, Paek D, Lee JO. Normal predictive values of spirometry in Korean population. Tubercul Respir Dis. 2005;58(3):230–42.

Bafadhel M, Peterson S, De Blas MA, Calverley PM, Rennard SI, Richter K, et al. Predictors of exacerbation risk and response to budesonide in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a post-hoc analysis of three randomised trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(2):117–26.

Yun JH, Lamb A, Chase R, Singh D, Parker MM, Saferali A, et al. Blood eosinophil count thresholds and exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(6):2037-47.e10.

Castaldi PJ, Benet M, Petersen H, Rafaels N, Finigan J, Paoletti M, et al. Do COPD subtypes really exist? COPD heterogeneity and clustering in 10 independent cohorts. Thorax. 2017;72(11):998–1006.

Wedzicha JA, Singh D, Vestbo J, Paggiaro PL, Jones PW, Bonnet-Gonod F, et al. Extrafine beclomethasone/formoterol in severe COPD patients with history of exacerbations. Respir Med. 2014;108(8):1153–62.

Barnes NC, Sharma R, Lettis S, Calverley PM. Blood eosinophils as a marker of response to inhaled corticosteroids in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(5):1374–82.

Anzueto AR, Kostikas K, Mezzi K, Shen S, Larbig M, Patalano F, et al. Indacaterol/glycopyrronium versus salmeterol/fluticasone in the prevention of clinically important deterioration in COPD: results from the FLAME study. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):121.

Pavord ID, Chanez P, Criner GJ, Kerstjens HAM, Korn S, Lugogo N, et al. Mepolizumab for eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(17):1613–29.

Watz H, Tetzlaff K, Wouters EF, Kirsten A, Magnussen H, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Blood eosinophil count and exacerbations in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids: a post-hoc analysis of the WISDOM trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(5):390–8.

Chapman KR, Hurst JR, Frent SM, Larbig M, Fogel R, Guerin T, et al. Long-term triple therapy de-escalation to indacaterol/glycopyrronium in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (SUNSET): a randomized, double-blind, triple-dummy clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(3):329–39.

Siddiqui SH, Guasconi A, Vestbo J, Jones P, Agusti A, Paggiaro P, et al. Blood eosinophils: a biomarker of response to extrafine beclomethasone/formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(4):523–5.

Jo YS, Hwang YI, Yoo KH, Kim TH, Lee MG, Lee SH, et al. Effect of inhaled corticosteroids on exacerbation of asthma-COPD overlap according to different diagnostic criteria. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(5):1625-33.e6.

Whittaker HR, Müllerova H, Jarvis D, Barnes NC, Jones PW, Compton CH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids, blood eosinophils, and FEV(1) decline in patients with COPD in a large UK primary health care setting. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:1063–73.

Celli BR, Thomas NE, Anderson JA, Ferguson GT, Jenkins CR, Jones PW, et al. Effect of pharmacotherapy on rate of decline of lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the TORCH study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(4):332–8.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Program funded Korea National Institute of Health (Fund CODE 2016ER670100, 2016ER670101, 2016ER670102, 2018ER67100, 2018ER67101, 2018ER67102, and 2021ER120500).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. YSJ, CKR, KHY, and YBP take responsibility for the data and analysis. YSJ, CKR, JYM, YHK, SJU, WJK, HKY, and KSJ designed the study and YSJ did statistical analysis of data. YSJ, CKR, KHY, and YBP wrote the initial manuscript. JYM, YHK, SJU, WJK, HKY, and KSJ provided critical review and approved of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All of the hospitals involved in the KOCOSS cohort obtained approval from the Institutional Review Board Committee and informed consent from their patients. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of KONKUK university medical center and all participants in the cohorts provided written informed consent (IRB No. KHH1010338). The present study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No, I declare that the authors have no competing interests as defined by BMC, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and/or discussion reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary Figure 1. Values of FEV: over follow-up period in patients with eosinophillic and non-eosinophillic COPD.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jo, Y.S., Moon, JY., Park, Y.B. et al. Longitudinal changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 s in patients with eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm Med 22, 91 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-022-01873-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-022-01873-8