Abstract

Background

Fungal infections are rarely reported as a complication of bronchial thermoplasty (BT) in patients without immunosuppressive comorbidity.

Case presentation

A 19-year-old woman college student was admitted to our hospital owing to uncontrolled severe asthma despite using the maximum dose of steroid inhalation. She experienced asthmatic attacks more frequently while cheerleading, which is an extracurricular activity. She received BT because she wanted to continue cheerleading. After the second BT session, she developed more sputum and cough. During the third session, white secretion and saccular bronchodilation appeared in the left lower bronchus. Aspergillus fumigatus was detected in the culture of the bronchial lavage sample, and saccular bronchodilation in the affected bronchus was observed on computed tomography (CT). Five months after the start of oral itraconazole, her subjective symptoms as well as her CT findings improved. Her asthma condition improved enough for the patient to continue cheerleading without exacerbation.

Conclusions

It is necessary to consider the possibility of respiratory tract infections including fungal infections after BT. Detailed observations of the entire bronchus and sample collection for microbial culture are highly recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bronchial thermoplasty (BT) is a medical procedure in which bronchoscopy is used and controlled thermal energy is applied to the bronchial wall to decrease the smooth muscles. This procedure is also effective for the treatment of severe asthma. Bronchial edema and radiological changes are commonly known major complications of BT, but infections are rarely reported. The AIR2 trial reported that only one patient with lower respiratory tract infection required hospitalization in the BT group [1]. Here, we present a case of aspergillosis after BT in a young asthmatic patient.

Case presentation

The patient was a 19-year-old woman with no comorbidities other than asthma. She was a non-smoker. She had been treated for severe asthma with high doses of inhaled corticosteroids plus long-acting β2-agonists, antileukotriene, theophylline, and antihistamine. The patient participated in cheerleading as an extracurricular activity at her college. During cheerleading, she experienced asthmatic attacks, which became increasingly frequent, and she therefore sought medical consultation. The patient wanted to continue cheerleading and enquired about strengthening her treatment. However, she did not want to take regular corticosteroids or antibody agents. She refused biological treatment owing to the cost associated with long-term continuation and the desire to have children. Therefore, the patient decided to undergo BT.

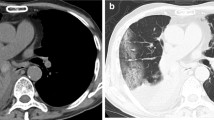

Chest computed tomography (CT) showed a thickened bronchial wall (Fig. 1a); the percentage forced expiratory volume (%FEV) was 86.2%, and exhaled nitric oxide was 45 ppm. Blood test results revealed the following: 515 U/mL, IgE; 8900/μL, white blood cell count; and 143/μL, eosinophils. The patient received 30 mg/day prednisolone for 3 days before BT treatment and continued it for 1 day post-BT treatment. The sessions for the right and left lower lobe were properly completed at 3-week intervals, and the BT activation numbers were 31 and 24 times, respectively (Fig. 2a).

Chest computed tomography images. a Left lower lobe with thickened bronchial wall before bronchial thermoplasty (BT). b Saccular bronchodilation of left lower bronchus (B9, B10) (arrows) and nodular consolidation (triangle) are seen 3 weeks after BT. c Bronchodilation and consolidation are improved 5 months after the start of oral itraconazole administration

After the second BT session, she developed more sputum and cough. During the third session, white secretion and saccular bronchodilation appeared in the left lower bronchus (B9 and B10) (Fig. 2b). At the same time, bronchial washing was performed. Her CT also showed saccular bronchodilation in the affected bronchus (Fig. 1b). Aspergillus fumigatus was detected in the bronchial lavage culture. Oral itraconazole administration was started, and serum β-d-glucan and aspergillus antigen were found to be negative. Five months later, the subjective symptoms and CT findings improved (Fig. 1c). Although respiratory function remained unchanged (%FEV, 88%), exhaled nitric oxide reduced to 15 ppm. After BT, the inhaled steroid dose was reduced owing to a remarkable improvement in asthma symptoms. The patient was able to continue her cheerleading activity without exacerbations.

Discussion and conclusions

Previous studies have evaluated the efficacy and safety of BT in patients with severe asthma. The AIR2 study showed that BT improved asthma-related quality of life (QOL) and significantly controlled the frequency of severe exacerbations [1]. In addition, the efficacy of BT can last for at least 5 years [2]. Moreover, Japanese patients with asthma had improved QOL, less exacerbations, less symptoms, and less obstructive pulmonary function after BT [3]. However, some complications associated with BT have been reported. Burn et al. reported that their BT patients experienced adverse events more frequently than those described in previous clinical trials [4]. Iikura et al. reported a case of aspergillus and nocardia infection after BT [5]: the patient was a 35-year-old man who regularly received systemic corticosteroids, which resulted in chronic immunodeficiency. In our case, the patient did not receive regular systemic corticosteroids, and the prophylactic steroid dose was 30 mg/body weight, which was less than the recommended dose of 50 mg/body weight in Japan [6]. In our experience, high-dose inhaled corticosteroids and minimal prophylactic systemic corticosteroids may cause fungal infections even in the absence of immunosuppressive comorbidities.

In addition, heat energy from BT may cause tissue fragility that predisposes the patient to respiratory tract infections [7]. However, in this case, the activation number for the left lower lobe was 24 times, which was much less than the average [6], and it developed while the damage to the respiratory tract was kept to a minimum. Potential respiratory aspergillosis has been previously reported in asthmatic patients who received inhaled corticosteroids [8, 9]. Hypothetically, it is considered that the mucosal defense is reduced following BT; thus, the pre-existing aspergillus molds become engrafted. In this case, aspergillosis was not tested for before performing BT. From this experience, pre-screening of chronic infections of the respiratory tract should be carried out. On the other hand, serum β-D-glucan and the aspergillus antigen were negative after occurring aspergillosis, the reason for the negative may be that the infection remained localized and the medication was started early. If the aspergillosis was not diagnosed and treated early, the bronchial deformity might have become irreversible.

We report a case of aspergillosis infection accompanied by saccular bronchodilation after BT. Regardless of the strength of asthma treatment and the absence of an immunosuppressive comorbidity, it is necessary to consider the possibility of respiratory tract infections, including fungal infections. Detailed observations of the entire bronchus and sample collection for microbial culture are highly recommended.

Availability of data and materials

All data and material are available for sharing if needed.

Abbreviations

- BT:

-

Bronchial thermoplasty

- CT:

-

Chest computed tomography

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- FEV:

-

Forced expiratory volume

References

Castro M, Rubin AS, Laviolette M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of bronchial thermoplasty in the treatment of severe asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:116–24.

Wechsler ME, Laviolette M, Rubin AS, et al. Bronchial thermoplasty—long term safety and effectiveness in severe persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1295–302.

Iikura M, Hojo M, Nagano N, et al. Bronchial thermoplasty for severe uncontrolled asthma in Japan. Allergol Int. 2018;67:273–5.

Burn J, Sims AJ, Keltie K, et al. Procedural and shorttermsafety of bronchial thermoplasty in clinical practice: evidence from a national registry and hospital episode statistics. J Asthma. 2016;1:1–8.

Matsubayashi S, Iikura M, Numata M, et al. A case of Aspergillus and Nocardia infections after bronchial thermoplasty. Respirol Case Rep. 2019;7:e00392.

Yamamoto S, Iikura M, Kakuwa T, et al. Can the number of radiofrequency activations predict serious adverse events after bronchial thermoplasty? A retrospective case-control study Pulm Ther. 2019;5:221–33.

Goorsenberg AWM, d’Hooghe JNS, de Bruin DM, et al. Bronchial thermoplasty-induced acute airway effects assessed with optical coherence tomography in severe asthma. Respiration. 2018;15:1–7.

Fairfax AJ, David V, Douce G, et al. Laryngeal Aspergillosis following high-dose inhaled fluticasone therapy for asthma. Thorax. 1999;54:860–1.

Leav BA, Fanburg B, Hadley S, et al. Invasive pulmonary Aspergillosis associated with high-dose inhaled fluticasone. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:586.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Masami Yoshihara, the medical interpreter and the medical coordinator at Tokyo Saiseikai Central Hospital for English language editing.

Funding

No funding sources were used.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript, and significantly contributed to this paper. SS, KO, TO, YF, SM, YT, KI, ST, MN, MK: Conception and design, literature review, manuscript writing and correction, final approval of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Appropriate written informed consent was obtained for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. It was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Saiseikai Central Hospital and was implemented (Approval Number 2020-010-1).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. This manuscript has not been published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. Additionally, all of the authors have approved the contents of this paper and have agreed to the journal´s submission policies.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sasada, S., Ohmura, K., Oguri, T. et al. A case report of aspergillosis accompanied by saccular bronchodilation after bronchial thermoplasty in a 19-year-old woman. BMC Pulm Med 20, 312 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-020-01352-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-020-01352-y