Abstract

Background

Although it is accepted that parents play a key role in forming children’s health behaviours, differences in parent-child physical activity (PA) have not previously been analysed simultaneously in random samples of families with non-overweight and overweight to obese preschool and school-aged children. This study answers the question which of the health-related parental indicators (daily step count (SC), screen time (ST), and weight status and participation in organized leisure-time PA) help their children achieve the step count recommendations.

Methods

A nationally representative sample comprising 834 families including 1564 parent-child dyads who wore the Yamax Digiwalker SW-200 pedometer for at least 8 h a day on at least four weekdays and both weekend days and completed a family log book (anthropometric parameters, SC, and ST). Logistic regression analyses were used to investigate whether parental achievement of the daily SC recommendation (10,000 SC/day), non-excessive ST (< 2 h/day), weight status, and active participation in organized PA were associated with children’s achievement of their daily SC (11,500 SC/day for pre-schoolers and 13,000/11,000 SC/day for school-aged boys/girls).

Results

While living in a family with non-overweight parents helps children achieve the daily SC recommendation (mothers in the model: OR = 3.50, 95% CI = 2.29–5.34, p < 0.001; fathers in the model: OR = 2.41, 95% CI = 1.37–4.26, p < 0.01) regardless of their age category, gender, or ST, for families with overweight/obese children, only the mother’s achievement of the SC recommendations and non-excessive ST significantly (p < 0.05) increase the odds of their children reaching the daily SC recommendation. The active participation of children in organized leisure-time PA increases the odds of all children achieving the daily SC recommendations (OR = 1.80–2.85); however, for overweight/obese children this remains non-significant. The participation of parents in organized leisure-time PA does not have a significant relationship to the odds of their overweight/obese or non-overweight children achieving the daily SC recommendations.

Conclusions

The mother’s health-related behaviours (PA and ST) significantly affect the level of PA of overweight/obese preschool and school-aged children. PA enhancement programmes for overweight/obese children cannot rely solely on the active participation of children in organized leisure-time PA; they also need to take other family-based PA, especially at weekends, into account.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to many theoretical models and theories [1,2,3,4] describing human behaviour, the direct influence of parents on the social development and behaviour of their children is firmly established. Parents have been termed the primary gatekeepers of their children’s health [5]. The parent-child physical activity (PA) or screen time relationship has been studied in a wide range of social [6], psychological [7, 8], educational, and health-related disciplines [9, 10], with an emphasis on healthy child development [6,7,8,9,10].

A focus on parent-child dyad analysis in preschool and preadolescent children is key to understanding the factors that are essential for shaping the active lifestyle of children, which persists until adulthood [11, 12]. Numerous longitudinal studies confirm the persistence of obesity arising in preschool age to adolescence [13, 14] and adulthood [15, 16]. An active lifestyle throughout childhood and adolescence could thus prevent the development of obesity in young adulthood [13]. Additionally, the relationship of parent-child overweight/obesity has already been proven to exist at preschool level [17,18,19]. Importantly, the risk of the transmission of obesity from childhood to adulthood seems to be stronger when a child has one obese parent than in obese children without obese parents [16].

Objective parent-child PA and screen time measurements have been analysed globally – Western Europe [7, 20,21,22] and Northern Europe [23], North and South America [17, 24,25,26,27,28,29], Africa and South Asia [17], and Australia and New Zealand [30, 31]. The emphasis in such studies is placed, for instance, on active parental participation in organized or non-organized PA [24, 26, 29, 31], parental support for PA [7, 8, 32, 33] and parenting styles [25, 32]. Other studies investigate role of parental rules and restrictions concerning screen time [30], parental education and family socioeconomic status [7, 17, 20, 21, 23, 30], variation in the weekday-weekend PA and screen time relationship [7, 24, 26, 27, 29, 33], and level of body weight [17, 20, 22, 27, 29, 34]. However, similarly valuable studies of objective parent-child PA and screen time measurements in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe are lacking.

Except for selected meta-analyses and reviews [35, 36], other parent-child PA/screen time studies are focused separately either on preschoolers [20, 22, 30, 31] or school-aged children and adolescents [7, 8, 17, 21, 24, 25, 27, 29, 32,33,34]. The parent-child PA/screen time relationship in a broader age spectrum of preschool and school-aged children is seldom analysed [26, 37]. In addition, parent-child PA/screen time relationships have been analysed only rarely in the countries of Central, Southern, and Eastern Europe [38, 39]. The countries of Central, Southern, and Eastern Europe, however, belong among those European countries that are challenged by the trend of an increase in childhood overweight/obesity [40, 41], screen time behaviours [42], and reduced PA [43]. Public health-related disciplines in these countries need to possess relevant information on the roles of families in shaping the active lifestyle of their children. It is because these countries tend to repeat the behavioural health-related patterns of children previously witnessed in children and adolescents from Western high-income countries, e.g. a decrease in PA, an increase in sedentary behaviours (especially screen time activities), an increase in the excessive consumption of sweetened beverages, and a greater intake of fast food [44]. Such behaviours consequently lead to increased rates of overweight and obesity [45,46,47]. Previous parent-child study [48] also pointed out that active participation of parent/children in organized PA as a promising “vehicle” to promote active lifestyle in children. However, it is not known whether active participation in leisure-time organized PA helps both healthy weight and overweight/obese children to reach PA recommendations. The selected physical activity behaviours are more easily modifiable, thus influenceable through eventual intervention programs or stimuli, than socioeconomic status, structure, or place of residence, which play their role too.

The study attempts to bridge the research gap of insufficient relevant information in Central European nations concerning the parent-child PA/screen time relationship in a random sample of Czech families with preschool and school-aged children whose body weight ranges from normal to overweight or obese with regard to the parents’ body weight and their participation in organized leisure-time PA.

This study aimed to estimate which of the health-related parental indicators (daily step counts, amount of screen-based entertainment time, weight status, and participation in organized leisure-time PA) help their preschool and school-aged children achieve their step count recommendations. Furthermore, we assessed whether the associations differ by gender of parents, weight status and participation in organized PA of children.

Methods

This research involved the use of data collected from the Czech-based Parent Child PA Care (PACPAC) Study. PACPAC is a three-cohort study that investigates the parent-child PA/screen time relationship in families with pre-schoolers (aged 3–6.49 years) and school-aged children (aged 6.5–12 years). This study collected data on parent-child dyads in the spring (from March until June) and autumn (from September until November) months between 2013 and 2016. The Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Physical Culture, Palacký University Olomouc approved the study design and protocol for families with school-aged children (ref. no. 17/2013) on 25 March 2013 and for families with preschool children (ref. no. 57/2014) on 10 December 2014.

Sample and inclusion criteria

Participants were recruited by means of two-stage stratified random sampling. In the first stage, nine out of 14 administrative regions, three of each in the lowest, middle, and highest terciles for gross domestic product in the Czech Republic, were randomly selected. In the second stage of sampling, the selection of kindergarten and primary schools respected the distribution of the urban-rural population in the Czech Republic [49]. A total of 296 families with preschool children and 1610 families with school-aged children were addressed in writing with an invitation to participate in the study before a joint meeting with the authors of the study. Participating children and their parents were predominantly white Caucasian (> 98%), which is representative of the ethnic demographics of the Czech Republic [50].

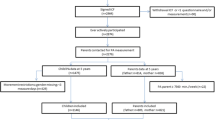

The disproportion of the sample in terms of age, i.e. higher number of school-aged children, was due to wider age range of school-aged children investigated compared with pre-schoolers. Furthermore, while school attendance is compulsory, kindergarten attendance (except for the last pre-school year is optional). The objectives, procedures/measures, and course of the project were thoroughly explained to the invited parents of the children and teachers and school/kindergarten employees at a joint meeting in each of the schools/kindergartens that participated. Written consent to participation in the study was obtained from 223 families with pre-schoolers (a response rate of 75%) and 1112 families with school-aged children (a response rate of 69%) at the end of the joint meeting (Table 1). The data of 38 families with preschool children and 463 families with school-aged children was not included in the analyses because of incompleteness (missing data on body weight, height, or age or an incomplete record of PA/screen time data in the family log book) or invalidity (an absence of more than 1 day of the child from kindergarten/school or insufficient (< 8 h) time spent wearing the pedometer each day). In accordance with the recommendations of previous studies [51, 52], the final analyses included only data from parent-child pairs (mother and child n = 707 and father and child n = 455) of participants who wore the pedometer for at least 8 h a day on at least four weekdays and both weekend days (Table 1).

Procedures and measures

During the baseline joint meeting the invited parents and kindergarten/school teachers were thoroughly acquainted with the procedures and course of the monitoring of PA and recording of the step count/screen time -related data into a family log book. The parents received instructions regarding how to use a pedometer and the process of recording the monitored values in the family log book. The family log book is composed of three sections – the first to record the anthropometric parameters of all the family members, the second for the PA-related data (step count, participation in organized PA), and the third for recording the screen time (type and duration) activities [53].

The parents were asked to record the demographic and anthropometric parameters (birth date of children and age of parents, gender, body height (with 0.5-cm accuracy), and weight (with 0.5-kg accuracy)) of all the participating family members in the first section of the family log book before the start of the one-week monitoring of PA/screen time behaviour. The parents were instructed how to measure their own body height and weight at home, as well as the height and weight of their children. The parental home measurement of the body weight and body height of their preschool [54] and school-aged children and adolescents [55] are sufficiently valid tools for determining the Body Mass Index (BMI) for the subsequent identification of overweight and obesity in children [55, 56].

The PA of all the participants in the three-cohort study was monitored using the same type of unsealed Yamax Digiwalker SW-200 pedometer (Yamax Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Participants were instructed to wear the pedometer on their right hip for eight consecutive days during waking hours except when bathing, showering, and dressing. Every morning after their personal hygiene, the parents reset the pedometers, attached them to the right hip (their children’s and their own), and recorded the time of the resetting in the family log book. In the evening, the parents removed the pedometers and, together with their children, recorded the time and overall daily step count of all the participating family members in the log book. In addition, parents also recorded whether they or their children actively participated in organized leisure-time PA during the day into the log book. Organized leisure-time PA covers all kinds of structured intentional PA performed under the guidance of an educator (such as teacher, coach, and instructor) and does not include lessons of physical education during school/kindergarten time [53]. Those who participated at least once a week, were considered to be participants in organized leisure-time PA. The values from the first day of monitoring were not included in the final analyses because of insufficient time spent wearing the pedometer and because of the novelty of wearing it, which could have affected the level of the participants’ PA [51]. The pedometer-based monitoring of ambulatory PA is an objective, cheap, and unobtrusive method providing a reasonable assessment of a child’s day-long PA, albeit only when the total amount of PA, not its intensity, is of interest [57, 58]. The good validity and reliability of the hip-worn Yamax Digiwalker SW-200 step count measurement support the use of the Digiwalker for assessing free-living PA in preschool [58] and school-aged children [57,58,59], as well as in adults [60].

The sedentary behaviour of all family members was self-reported in the family log book by the parents. However, rather than all types of sedentary behaviours, attention was focused on screen time activities only, since they allow more accurate discrimination of health-risk behaviours than total sedentary behaviour does [61, 62]. The duration and type of entertainment screen time (sitting/lying while watching TV and sitting/lying in front of a PC (notebook, tablet, or smartphone) and not for school/work purposes) was recorded with an accuracy of 10 min by the parents, together with their children, each evening. The parent-proxy assessment of the amount of time their children spent watching TV daily exhibits an acceptable 7-to-14-day test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.78, p < 0.001) [63] and shows a strong positive correlation with direct home time-lapse videos (r = 0.84, p < 0.001) [64].

Data management

The step count/screen time data was reviewed to check for extreme values. The daily step count variable represented the mean difference between the morning (pedometer turned on) and evening (pedometer turned off) step count/screen time on the days of the week that were monitored. Daily step count values below 1000 or exceeding 30,000 were truncated to these recommended limit values, respectively [37, 51], and included in the analyses. Weekly averages were calculated by adding 2/7 of the weekend day average and 5/7 of the weekday average. If step count and screen time were recorded on four weekdays, data for the one missing weekday based on the participant’s personal mean scores was added. The participants whose step count/screen time data was missing for more than 1 day were excluded from the analyses. The daily step count recommendation for preschool children was set at a value of 11,500 steps/day [65]. For school-aged children, a value of 13,000 steps/day was applied for boys and 11,000 steps/day for girls [53, 66], and for adults it was a value of 10,000 steps/day [67]. Daily screen time shorter than 10 min was not counted and if it was longer than 14 h it was shortened to this recommended value [53]. Excessive screen time for preschool children was defined as more than 1 h/day [68, 69] and for school-aged children [61, 62] and for adults as two or more hours a day [70].

The BMI was calculated as the body weight (kg) divided by the square of body height (m). The chronological age of all family members was calculated from their date of birth until the first monitoring day. Age-specific cut-off points [71,72,73] were used to define the prevalence of overweight/obesity. Overweight or obesity in children is represented by a BMI from the 85th to 97th or greater than the 97th percentile of the WHO growth charts, respectively [71, 72]. Overweight and obesity in parents is represented by a BMI from 25 kg/m2 to 29.9 kg/m2 and greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2, respectively [73].

Statistical analyses

Descriptive characteristics for the daily step count, prevalence of overweight and obesity, percentages of participants who met the daily step count recommendations, percentages of participants with excessive daily screen time, and frequency of participation in organized leisure-time PA were calculated for all family members (girls, boys, mothers, and fathers) separately. Summary sample characteristics are represented by means and standard deviations. The daily step count data is presented in the form of means and a 95% confidence interval or percentages. Logistic regression models (Enter Method) were used to identify which family-related variables (achievement of the recommended daily step count, excessive screen time, parental overweight/obesity, participation in organized leisure-time PA, and the gender of children) were associated with children of normal body weight and overweight/obese children achieving the step count recommendations separately). The models were adjusted for age category and gender of children. We used ordinary single-level regression, because initial analyses were not significantly altered by clustering of data by school/kindergarten. An independent t-test (2-tailed) was used to compare the daily step count (as presented in Fig. 1) of participants and non-participants in organized leisure-time PA split by gender and the level of body weight of the children. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows v.22 software (IBM Corp. Released 2013. Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data management and all statistical analyses. The alpha level of significance was set at the minimum value of 0.05 for all the statistical analyses.

Comparison of children’s daily step counts (mean and 95% CI) on weekdays and at weekends. Legend: CI – confidence interval; x – mean number of sessions of organized leisure-time PA per week. The statistical significance of the differences between participants in organized PA and non-participants in terms of their daily step count (independent t-test (2-tailed)) is expressed as *p < 0.05 and ‡p < 0.001

Results

Among the children (420 girls and 414 boys), the prevalence of overweight was observed in 13.6% (7.6% were classified as obese) of the girls and 14.0% (10.9% were classified as obese) of the boys. Of the 185 preschoolers, the incidence of overweight was detected in 7.6% (and that of obesity in 9.2%) of them, while among the school-aged children the representation of overweight amounted to 15.6% (and that of obesity to 9.3%) out of the total number of 649 school-aged children (Table 1).

The relationship between children’s PA and parental indicators of health-related behaviours is presented in Table 2. Using the binary measures of achieving the recommended levels of daily step count, we found strong positive associations between mothers’ and children’s step count (p < 0.05), regardless of the maternal and children’s level of body weight. Fathers’ PA and level of body weight were only significantly associated with non-overweight children achieving the daily step count recommendation (Table 2).

While achievement of the recommended step count level by fathers significantly increased the odds of non-overweight children achieving the daily step count recommendations, parental overweight/obesity status significantly reduced these odds. The active participation of parents in organized leisure-time PA, regardless of their gender, did not significantly affect the odds of their children achieving the daily step count recommendations, regardless of their level of body weight. Conversely, non-overweight children participating in organized leisure-time PA at least once weekly were more likely to meet the recommended daily step count levels than their counterparts without organized leisure-time PA.

The active participation of children in organized leisure-time PA (at least once a week) was positively associated with a significantly higher daily step count on weekdays in non-overweight and overweight/obese boys in comparison with non-participants in such activities (Fig. 1). The significant difference in the daily step count between boys (girls) who participated in organized leisure-time PA and those who did not do so ranged from 1764 to 2152 (1408–1471) steps on weekdays. Except for non-overweight boys, no significant differences in the daily step count at weekends were found in terms of gender and body weight between participants and non-participants in organized leisure-time PA. For all children, regardless of gender, body weight, or participation in organized PA, a lower daily step count was visible at weekends than on school days (Fig. 1).

Discussion

The plethora of studies confirm the influential role of parents on the PA of their children through a variety of mechanisms, including parents taking responsibility for PA care [33], support [8, 35, 36], encouragement [7], and engagement [33]. Nonetheless, it has not yet been explained sufficiently which of the parental health-related indicators help children achieve the recommended level of PA or how these indicators vary between non-overweight and overweight/obese children. The results of this three-cohort study extend the current knowledge in the area of the parent-child PA relationship in a random sample of families with non-overweight and overweight/obese preschool and school-aged children. Another original feature of the present study is represented by the gender- and age category-stratified analyses of daily step count (specifically, the achievement of the daily step count recommendations) in all the members of families with non-overweight and overweight/obese children.

In response to the specific objective of the study, it was revealed that maternal achievement of PA recommendation (≥ 10,000 steps/day) significantly helped all children, regardless of their body weight, to reach the recommended daily step count. And furthermore, the active participation of children in organized leisure-time PA increased the odds of all children achieving the daily step count recommendations; however, for overweight/obese children this remained non-significant. Many studies confirmed that there is a positive relationship between the objectively monitored PA (or proxy-reported screen time) of parents and their children [10, 17, 22,23,24, 26, 28, 37, 39, 74, 75]. However, only a few of them focused on the analyses of the parent-child relationship in terms of meeting the PA/screen time recommendations (daily hours of screen time [10, 75, 76]; pedometer-determined daily step count [39]; minutes spent daily on moderate-to-vigorous accelerometer-based PA [17]), or categorizing the level of PA/screen time (median of moderate-to-vigorous accelerometer-based PA [24]; median of Caltrac accelerometer counts per hour [28]; tertile of pedometer-determined daily step count [37]). The present study therefore adds to the body of knowledge regarding the existence of a relationship between parents’ and children’s achievement of the PA recommendations.

Similarly to other studies [22, 23, 26, 34], we found stronger positive relationships between mother-child PA than father-child PA in families with both non-overweight and overweight/obese children. In addition to those studies, we found that in families with overweight/obese children the mother’s behaviour (PA and screen time) is even more closely associated with their children’s PA than that of the father. On the other hand, only fathers’ body weight had a negative effect on the odds of their children meeting the step count recommendations. No such association was observed in our study regarding mothers’ body weight. Perhaps overweight/obese children are more likely to adopt patterns of parental behaviour than children of normal body weight. This idea is supported by the finding of lower differences in the daily step count among individual members of families with overweight/obese children compared to families with non-overweight children, where the child’s PA exceeds the parental activity.

The active participation of parents in organized leisure-time PA did not affect the odds of overweight/obese or non-overweight children achieving the daily step count recommendation. In one of the rare studies on the topic, Erkelenz et al. [77] also analysed the relationship of parental PA and the participation of their six-to-eight-year-old children in organized sports in addition to parent-child PA. They did not observe relationship between parental and children’s PA; however, children with at least one active parent displayed more minutes of participation in organized sports. The absence of a parent-child PA relationship but a higher level of participation of children in organized sport in the event of there being at least one more active parent indicates that parental support for children’s PA could be more important than parents’ joint PA [77]. The greater significance of parental support for children’s PA than of parent-child PA is also highlighted by meta-analytical studies [35, 36], which also encourage further verification of the relationship between parent-child PA and various types of parental support for their children’s PA and their children’s actual PA.

The present study showed that an active participation in organized leisure-time PA (at least once a week) is the only one of the anthropometric and behavioural correlates of non-overweight children that was analysed which significantly increased the odds of daily step count recommendations being met. In the case of overweight/obese children, active participation in organized leisure-time PA doubled the chance of their reaching the daily step count recommendation compared to those not attending organized leisure-time PA, but the result was not significant. Previous studies documented the positive contribution to the all-day objectively monitored PA of active participation in physical education lessons (step count, moderate-to-vigorous PA) in boys of normal weight and overweight/obese girls aged 9–11 [78, 79]. In addition, these studies reported a significantly higher proportion of boys of normal weight and overweight/obese girls who met the recommendation of 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous PA per day on a day with active participation in a physical education lesson than on a day without a physical education lesson. Therefore, it was expected that active participation in organized leisure-time PA would increase the chance of both non-overweight and overweight/obese children achieving the daily step count recommendations. However, a study among Finnish preschoolers did not reveal differences in light PA or moderate-or-vigorous PA among participants and non-participants in organized PA or between children of normal weight and overweight/obese children [23]. Significant differences in daily PA between participants and non-participants in organized leisure-time PA and between children of normal weight and overweight/obese children, as well as differences in PA between school days and weekend days, appear to be evident only after children start attending primary school [26, 27, 53].

We concur with the idea that parental correlates relating to PA and the overweight/obesity of their children are related in different ways in developing versus developed countries [17], and there is still a need for more detailed disclosure of parent-child PA relationships. The challenge lies in determining ways to effectively motivate and support parents and other caregivers of young children to optimize practices related to young children’s health-related behaviours [80]. There are several parental correlates of the objectively measured PA of preschool and school-aged children from Central and Eastern Europe that should receive more attention. It is necessary to include socioeconomic status of families and the level of parental education [7, 20, 23, 30, 81], incompleteness of families [6, 21], PA and support from classmates and siblings [7, 8], and the type of residence and quality of the neighbourhood [21].

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this three-cohort parent-child study is the involvement of all family members with preschool and school-aged children in the simultaneous monitoring of week-long ambulatory PA and screen time, as proxy-reported by parents. Moreover, contrary to comparable international studies [36, 80], the present research used stricter inclusion criteria for the final data analysis. Only data from children and their parents whose PA and screen time were monitored continuously for at least 8 h a day on at least four weekdays and both weekend days were analyses. This strictness provides a more valid comparison of the duration of parents’ and children’s daily step count and screen time between weekdays and weekend days, and helps reveal the variables increasing the odds of overweight/obesity among four-to-12-year-old Czech children. Another strength of the study is that the total amount of daily PA is supplemented with information about participation in organized sport.

However, the conclusions of any study need to be formulated under the spotlight of existing methodological limitations. Firstly, although the parental proxy-reported variables of their children’s health-related behaviour (PA and screen time) are considered to be valid and reliable for assessing PA and screen time levels, there is always a possible bias caused by social desirability. However, the parents, kindergarten/school teachers, and children were not told what age and gender-related step count and screen time recommendations exist prior to the commencement of the eight-day monitoring of PA or during it. Moreover, the data from the first day of measurement was also excluded from the final data analysis because the recording of the first day was incomplete and the novelty of wearing the Yamax pedometer might have affected the initial activity (reactivity) [51]. Second, the PACPAC study uses pedometers to objectively capture PA, but unlike accelerometers, these pendulum arm tools are not designed to collect information on bouts, type or, in particular, the intensity of PA. However, these less expensive devices are recommended as an inexpensive, small-sized, easy-to-use, and objective (valid, reliable, and non-reactive) method that provides a summary output of daylong ambulatory PA (quantified as the step count) of preschool [82, 83] and school-aged children [84] and adults [67] for the categorization of their achievement of the step count recommendations. Third, large differences in sample size and response rate of families with preschool and school-aged children could have a potential impact on the results of PA/screen time results. Families with preschool children were more likely to meet the inclusion criteria for weekly PA/screen time monitoring and provide valid anthropometric, PA/screen time data than families with school-aged children. It may seem that attitude of families with preschool children to research is more responsible compared to families with school children; but in families with school-aged children, a lower response rate could imply more time spent on school duties and the start of childhood puberty. Finally, the cross-sectional design of this study does not allow the causality of the parent-child PA relationships to be ascertained, despite their statistical significance. However, given the age of preschoolers and school-aged children, it is more likely that parent health-related behaviour affects the behaviour of children than vice versa.

Conclusions

Altogether, the results of this study underline the differences in the parent-child PA relationship between families with non-overweight and overweight/obese children and highlight the effect of maternal health-related behaviour on their children’s PA. The mother’s achievement of PA recommendation (≥ 10,000 steps/day) significantly helps all children, regardless of their body weight, to reach the recommended daily step count. Conversely, excessive screen time (≥ 2 h per day) in the mothers of overweight/obese children significantly reduces the odds of their achieving the recommended daily step count. Whilst the active participation of parents in organized leisure-time PA is not related to their children’s PA, the active participation of children in organized leisure-time PA almost doubles or even multiplies the odds of their meeting the daily step count recommendation in both non-overweight and overweight/obese children. Involving all family members in inexpensive PA enhancement programmes (especially at weekends) and increasing the participation of all boys and girls, regardless of body weight and age category, in organized leisure-time PA could be a promising part of strategies for increasing daily PA and shaping an active lifestyle.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ICC:

-

Intra class correlation

- LR:

-

Logistic regression

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- PC:

-

Computer use

- Ref.:

-

Reference group

- SC:

-

Step count

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for the social sciences

- ST:

-

Screen time

- TV:

-

Television viewing

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Biddle SJH, Nigg CR. Theories of exercise behavior. Int J Sport Psychol. 2000;31:290–304.

Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: research perspectives. Dev Psychol. 1986;22:723–42.

Bandura A. Social learning theory. New York: General Learning Press; 1977.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman; 1997.

Case A, Paxson C. Parental behavior and child health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21:164–78.

Carson V, Stearns J, Janssen I. The relationship between parental physical activity and screen time behaviours and the behaviours of their young children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2015;27:390–5.

McMinn AM, Griffin SJ, Jones AP, van Sluijs EMF. Family and home influences on children’s after-school and weekend physical activity. Eur J Pub Health. 2013;23:805–10.

Prochaska JJ, Rodgers MW, Sallis JF. Association of parent and peer support with adolescent physical activity. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2002;73:206–10.

Lampard AM, Jurkowski JM, Davison KK. The family context of low-income parents who restrict child screen time. Child Obes. 2013;9(5):386–92.

Wijtzes AI, Jansen W, Kamphuis CBM, Jaddoe VWV, Moll HA, Tiemeier H, et al. Increased risk of exceeding entertainment-media guidelines in preschool children from low socioeconomic background: the generation R study. Prev Med. 2012;55:325–9.

Kaseva K, Hintsa T, Lipsanen J, Pulkki-Råback L, Hintsanen M, Yang X, et al. Parental physical activity associates with offspring’s physical activity until middle age: a 30-year study. J Phys Act Health. 2017;14:520–31.

Telama R, Yang X, Leskinen E, Kankaanpää A, Hirvensalo M, Tammelin T, et al. Tracking of physical activity from early childhood through youth into adulthood. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:955–62.

Kwon S, Janz KF, Letuchy EM, Burns TL, Levy SM. Active lifestyle in childhood and adolescence prevents obesity development in young adulthood. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23:2462–9.

Shankaran S, Bann C, Das A, Lester B, Bada H, Bauer CR, et al. Risk for obesity in adolescence starts in early childhood. J Perinatol. 2011;31:711–6.

Guo S, Huang C, Maynard L, Demerath E, Towne B, Chumlea WC, et al. Body mass index during childhood, adolescence and young adulthood in relation to adult overweight and adiposity: the Fels longitudinal study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1628–35.

Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz W. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:869–73.

Muthuri SK, Onywera VO, Tremblay MS, Broyles ST, Chaput JP, Fogelholm M, et al. Relationships between parental education and overweight with childhood overweight and physical activity in 9-11 year old children: results from a 12-country study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147746.

Parrika S, Mäki P, Levälahti E, Lehtinen-Jacks S, Martelin T, Laatikainen T. Associations between parental BMI, socioeconomic factors, family structure and overweight in Finnish children: a path model approach. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:271.

Kitsantas P, Gaffney KF. Risk profiles for overweight/obesity among preschoolers. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:563–8.

Hesketh KR, McMinn AM, Ekelund U, Sharp SJ, Collings PJ, Harvey NC, et al. Objectively measured physical activity in four-year-old British children: a cross-sectional analysis of activity patterns segmented across the day. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:1.

Pouliou T, Sera F, Griffiths L, Joshi H, Geraci M, Cortina-Borja M, et al. Environmental influences on children’s physical activity. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:77–85.

Sijstma A, Sauer PJJ, Corpeleijn E. Parental correlation of physical activity and body mass index in young children- the GECKO Drenthe cohort. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:132.

Matarma T, Tammelin T, Kulmala J, Koski P, Hurme S, Langström H. Factors associated with objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time of 5–6-year-old children in the STEPS study. Early Child Dev Care. 2017;187:1863–73.

Fuemmeler BF, Anderson CB, Mâsse LC. Parent-child relationship of directly measured physical activity. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:17.

Hennessy E, Hughes SO, Goldberg JP, Hyatt R, Economos CD. Parent-child interactions and objectively measured child physical activity: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:71.

Jacobi D, Caille A, Borys J-M, Lommez A, Couet C, Charles M-A, et al. Parent-offspring correlations in pedometer-assessed physical activity. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29195.

McMurray RG, Berry DC, Schwartz TA, Hall EG, Neal MN, Li S, et al. Relationships of physical activity and sedentary time in obese parent-child dyads: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:124.

Moore LL, Lombardi DA, White MJ, Campbell JL, Oliveria SA, Ellison RC. Influence of parents’ physical activity levels on activity levels of young children. J Pediatr. 1991;118:215–9.

Tu AW, Watts AW, Masse LC. Parent-adolescent patterns of physical activity, sedentary behaviors and sleep among a sample of overweight and obese adolescents. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12:1469–76.

Downing KL, Hinkley T, Hesketh KD. Associations of parental rules and socioeconomic position with preschool children’s sedentary behaviour and screen time. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12:515–21.

Oliver M, Schofield GM, Schluter PJ. Parent influences on preschoolers’ objectively assessed physical activity. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13:403–9.

Langer SL, Crain AL, Senso MM, Levy RL, Sherwood NE. Predicting child physical activity and screen time: parental support for physical activity and general parenting styles. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39:633–42.

Vander Ploeg KA, Kuhle S, Maximova K, McGavock J, Wu B, Veugelers PJ. The importance of parental beliefs and support for pedometer-measured physical activity on school days and weekend days among Canadian children. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1132.

Griffith JR, Clasey JL, King JT, Gantz S, Kryscio RJ, Bada HS. Role of parents in determining children’s physical activity. World J Pediatr. 2007;3:265–0.

Gustafson SL, Rhodes RE. Parental correlates of physical activity in children and early adolescents. Sports Med. 2006;36:79–97.

Yao CA, Rhodes RE. Parental correlates in child and adolescent physical activity: a meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:10.

Craig C, Cameron C, Tudor-Locke C. CANPLAY pedometer normative reference data for data for 21,271 children and 12,956 adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:123–9.

Sigmundova D, Sigmund E, Vokacova J, Kopcakova J. Parent-child associations in pedometer-determined physical activity and sedentary behaviour on weekdays and weekends in random sample of families in the Czech Republic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:7163–81.

Sigmundová D, Sigmund E, Badura P, Vokacova J, Trhlikova L, Bucksch J. Weekday-weekend patterns of physical activity and screen time in parents and their pre-schoolers. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:898.

Ahluwalia N, Dalmasso P, Rasmussen M, Lipsky L, Currie C, Haug E, et al. Trends in overweight prevalence among 11-, 13- and 15-years-olds in 25 countries in Europe, Canada and USA from 2002 to 2010. Eur J Pub Health. 2015;25(Suppl 2):28–32.

Wang Y, Lobstein T. Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2006;1:11–25.

Bucksch J, Sigmundova D, Hamrik Z, Troped PJ, Melkevik O, Ahluwalia N, et al. International trends in adolescent screen time behaviors from 2002 to 2010. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58:417–25.

Kalman M, Inchley J, Sigmundova D, Iannotti RJ, Tynjälä JA, Hamrik Z, et al. Secular trends in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in 32 countries from 2002 to 2010: a cross-national perspective. Eur J Pub Health. 2015;25(Suppl 2):37–40.

Berghöfer A, Pischon T, Reinhold T, Apovian CM, Sharma AM, Willich SN. Obesity prevalence from a European perspective: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:200.

Lakshman R, Elks CE, Ong KK. Childhood obesity. Circulation. 2012;126:1170–9.

Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Suger-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;84:274–88.

Wang Y, Lim H. The global childhood obesity epidemic and the association between socio-economic status and childhood obesity. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2012;24:176–88.

Sigmund E, Sigmundová D. Parent-child physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and obesity. 1st ed. Olomouc: Palacký University Olomouc; 2017. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5507/ftk.17.24451824

Ritschelová I, Boušková M, Holý D, Hrbek J, Kadlecová I, Konečný F, et al. Statistical Yearbook of the Czech Republic. 1st ed. Prague: Scientia, Czech Republic; 2012.

Ritschelová I, Bartoňová E, Rojíček M. Demographic yearbook of the Czech Republic 2014. 1st ed. Prague: Czech statistical Office; 2015. Code: 130067–15

Rowe DA, Mahar MT, Raedeke TD, Lore J. Measuring physical activity in children, with pedometers: reliability, reactivity, and replacement of missing data. Ped Exerc Sci 2004. 2004;16:343–54.

Trost SG, Pate RR, Freedson PS, Sallis JF. Using objective physical activity measures with youth: how many days of monitoring are needed? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:426–31.

Sigmund E, Sigmundová D. School-related physical activity, lifestyle and obesity in children. 1st ed. Olomouc: Palacký University in Olomouc; 2014. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5507/ftk.14.24439266

Huybrechts I, Himes JH, Ottevaere C, De Vriendt T, De Keyzer W, Cox B, et al. Validity of parent-reported weight and height of preschool children measured at home or estimated without home measurement: a validation study. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:63.

Chan NPT, Choi KC, Nelson EAS, Sung RYT, Chan JCN, Kong APS. Self-reported body weight and height: an assessment tool for identifying children with overweight/obesity status and cardiometabolic risk factors clustering. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17:282–91.

Stommel M, Schoenborn A. Accuracy and usefulness of BMI measures based on self-reported weight and height: findings from the NHANES & NHIS 2001-2006. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:421.

Hands B, Parker H, Larkin D. Physical activity measurement methods for young children: a comparative study. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2006;10:203–14.

McNamara E, Hudson Z, Taylor SJC. Measuring activity levels of young people: the validity of pedometers. Br Med Bull. 2010;95:121–37.

Kilanowski CK, Consalvi AR, Epstein LH. Validation of an electronic pedometer for measurement of physical activity in children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 1999;11:63–8.

Kooiman TJM, Dontje ML, Sprenger SR, Krijnen WP, van der Schans CP, de Groot M. Reliability and validity of ten consumer activity trackers. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2015;7:24.

Chaput JP, Saunders TJ, Mathieu MÈ, Henderson M, Tremblay MS, O’Loughlin J, et al. Combined associations between moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary behaviour with cardiometabolic risk factors in children. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013;38:477–83.

Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Kho ME, Saunders TJ, Larouche R, Colley RC, et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:98.

Salmon J, Campbell KJ, Crawford DA. Television viewing habits associated with obesity risk factors: a survey of Melbourne schoolchildren. Med J Aust. 2006;184:64–7.

Anderson DR, Field DE, Collins PA, Lorch EP, Nathan JG. Estimates of young children’s time with television: a methodological comparison of parent reports with time-lapse video home observation. Child Dev. 1985;56:1345–57.

De Craemer M, De Decker E, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Verloigne M, Manios Y, Cardon G. The translation of preschoolers’ physical activity guidelines into a daily step count target. J Sports Sci. 2015;33:1051–7.

Tudor-Locke C, Craig C, Beets MW, Belton S, Cardon GM, Duncan S, et al. How many steps/day are enough? For children and adolescents. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:78.

Tudor-Locke C, Craig C, Brown W, Clemes S, De Cocker K, Giles-Corti B, et al. How many steps/day are enough? For adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:79.

Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing. Get up and grow: Healthy eating and physical activity for early childhood. Staff and carer book. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/phd-gug-staffcarers Accessed 7 December 2017.

Pyper E, Harrington D, Manson H. The impact of different types of parental support behaviours on child physical activity, healthy eating, and screen time: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:568.

Tremblay MS, Colley RC, Saunders TJ, Healy GN, Owen N. Physiological and health implications of a sedentary lifestyle. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2010;35:725–40.

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:660–7.

Growth reference data for 5–19 years. WHO Reference 2007. http://www.who.int/growthref/en. Accessed 24 May 2017.

WHO. Obesity and overweight. Fact sheet No°311 http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/. Accessed 24 May 2017.

Jago R, Sebire SJ, Wood L, Pool L, Zahra J, Thompson JL, et al. Associations between objectively assessed child and parental physical activity: a cross-sectional study of families with 5-6 year old children. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:655.

Jago R, Davison KK, Thompson JL, Page AS, Brockman R, Fox KR. Parental sedentary restriction, maternal parenting style, and television viewing among 10- to 11-year-olds. Pediatrics. 2011;128:572–8.

Jago R, Thompson JL, Sebire SJ, Wood L, Pool L, Zahra J, et al. Cross-sectional associations between the screen-time of parents and young children: differences by parent and child gender and day of the week. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:54.

Erkelenz N, Kobel S, Kettner S, Drenowatz C, Steinacker JM. Parental activity as influence on children’s BMI percentiles and physical activity. J Sports Sci Med. 2014;13:645–50.

Sigmund E, Sigmundová D, Hamrik Z, Madarásová Gecková A. Does participation in physical education reduce sedentary behaviour in school and throughout the day among normal-weight and overweight-to-obese Czech children aged 9-11 years? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:1076–93.

Sigmund E, Sigmundová D, Šnoblová R, Gecková AM. ActiTrainer-determined segmented moderate-to-vigorous physical activity patterns among normal-weight and overweight-to-obese Czech schoolchildren. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:321–9.

Cardon G, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Iotova V, Latomme J, Socha P, Koletzko B, et al. Health related behaviours in normal weight and overweight preschoolers of a large pan-european sample: the ToyBox-study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150580.

Stearns JA, Rhodes R, Ball GDC, Boule N, Veugelers PJ, Cutumisu N, et al. A cross-sectional study of the relationship between parents’ and children’s physical activity. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1129.

Cardon G, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Comparison of pedometer and accelerometer measures of physical activity in preschool children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2007;19:205–14.

Pagels P, Boldemann C, Raustorp A. Comparison of pedometer and accelerometer measures of physical activity during preschool time on 3- to 5-year-old children. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:116–20.

Peters BP, Kate A, Abbey BM. Validation of Omron™ pedometers using MTI accelerometers for use with children. Int J Exerc Sci. 2013;6:106–13.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all children and parents for participation in the study. Special thanks go to the school management members who helped facilitate the research.

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant from the Czech Science Foundation under reg. No. 16-14620S titled “Association between physical activity behaviour in parents and their children: A three-cohort study of children aged 4-12 years”. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the study.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author ES. The data are not publicly available due to rules of funded projects.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DS conceived the study, obtained the funding, and led manuscript writing. DS, ES, and PB prepared a research protocol survey and participated in data collection. DS and ES undertook the data analysis and interpreted the results. ES and AMG wrote the core of the manuscript with inputs from DS and PB. ES and AMG revised the manuscript during the review process. All authors interpreted, read and approved the final version of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics committee of the Faculty of Physical Culture, Palacký University on 25th March 2013 for families with school-aged children (ref. no. 17/2013), and on 10th December 2014 for families with preschool children (ref. no. 57/2014). All children, teachers, and school management received detailed information on the design and purpose of the survey at a meeting at each of the participating schools. Participation of children and parents in each part of data collection was voluntary and without any financial incentives. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Parents consented to the inclusion of their children in this study. All participating members received feedback on the overall school results after data processing.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Dr. Erik Sigmund is an Associate Editor for BMC Public Health.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sigmund, E., Sigmundová, D., Badura, P. et al. Health-related parental indicators and their association with healthy weight and overweight/obese children’s physical activity. BMC Public Health 18, 676 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5582-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5582-7