Abstract

Background

Varicella is normally a self-limited childhood disease caused by varicella-zoster virus infection. However, it sometimes causes severe diseases, especially in immunocompromised individuals. We report a case of severe varicella in a young woman.

Case presentation

A 19-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain and a rash after taking methylprednisolone for 2 weeks for systemic lupus erythematosis. The laboratory data showed leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, an elevated level of the liver transaminases and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed multiple air-fluid levels in the intestines. Hemorrhagic varicella was considered and antiviral therapy as well as immunoglobin were applied. Her condition deteriorated and she eventually died due to multi-organ failure and refractory shock. Next-generation sequencing performed on fluid from an unroofed vesicle confirmed the diagnosis of varicella.

Conclusion

In its severe form, VZV infection can be fatal, especially in immunocompromised patients. Hemorrhagic varicella can be misdiagnosed by clinicians because of unfamiliar with the disease, although it is associated with a high mortality rate. In patients with suspected hemorrhagic varicella infection, antiviral therapies along with supportive treatment need to be initiated as soon as possible in order to minimize the case fatality rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Varicella is normally a self-limited disease caused by varicella-zoster virus(VZV) infection. However, it sometimes causes severe diseases, especially in immunocompromised individuals such as those are taking chemotherapy or steroid therapy, and those who have had a renal transplant or a bone marrow transplant [1,2,3,4]. Few immunocompetent hosts were also involved [5, 6].

We describe a case of atypical varicella in a woman who presented with abdominal pain and a rash after being treated with methylprednisolone.

Case presentation

A 19-year-old Chinese woman was admitted to the emergency department of our hospital because of a three-day absence of defecation and a one-day history of abdominal pain. Two weeks previously, she had been discharged from the Department of Dermatology with a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus(SLE). She was being treated with methylprednisolone at a dose of 24 mg per day.

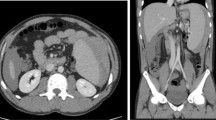

On examination, there was a diffuse brown pigmentation on the skin, with vesiculopapular rash on the forehead and over the trunk (Fig. 1). There was tender on palpation of the epigastric area, without rebound or guarding. The intestinal sounds were diminished. No palpable abdominal mass or hepatosplenomegaly was observed. The emergency computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed multiple air-fluid levels in the intestines. Intestinal obstruction was suspected (Fig. 2a) and an emergency surgery was arranged. Before surgery, laboratory testing revealed leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia and elevated liver transaminases. In addition, prolonged prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time, decreased fibrinogen and increased D-dimer level indicated disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)(Table 1). The surgery was therefore cancelled, and plasma and prothrombin complex were administered. Gastrointestinal decompression was implemented and then plenty of blood was drained out. Four hours after admission, she suffered from an epileptic seizure for five minutes. Cranial CT ruled out intracranial hemorrhage, but a repeated abdominal CT showed an increased amount of free gases and fluids in the colon (Fig. 2b) and cystorrhagia was suspected (Fig. 2c). A urinary catheter was inserted and hematuria was observed. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit to monitor vital signs more closely. Hemorrhagic varicella was considered and antiviral therapy of ganciclovir at 2.5 mg/kg/day as well as immunoglobin at 20 g/day were applied. However, six hours after admission, her blood pressure stared to decrease and norepinephrine was administered. Twelve hours after admission, repeated laboratory testing showed non-corrected leukocytosis and thrombocytopenia, elevated liver transaminases and a considerably prolonged prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time. In addition, anemia and elevated creatinine was also revealed (Table 1). Then, blood oxygen saturation started to decrease and a trachea cannula was carried out. Eighteen hours after admission, the patient died due to multi-organ failure and refractory shock. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) performed on fluid from an unroofed vesicle confirmed the diagnosis of varicella (the reads of human herpes virus 3 is 32,486, accounting for 99.90%).

CT of the abdomen. a. The CT scan shows multiple air-fluid levels in the bowels suggestive of bowel obstruction on admission. b. The CT scan shows extensive free gases and fluids in the colon four hours after admission. c. The CT scan shows a high density mass in the bladder suggestive of cystorrhagia four hours after admission

Discussion and conclusions

In its severe form, VZV infection can be fatal, especially in immunocompromised patients. Visceral disseminated disease is associated with a high mortality rate of 46–55% [7]. In normal varicella infection, as Kole AK et al. reported, hemorrhage vesicle is a relative unusual complication occurred in 3.3% of the patients [8]. However, it’s more common in visceral disseminated varicella. In a report of 38 cases of visceral disseminated varicella, rash was the presenting complaint in 89% of the cases [9]. However, some patients have no skin involvement, which probably leads to misdiagnosis and poses diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, especially when some other disease manifestations exist [7, 10]. Despite skin involvement, the symptoms of disseminated varicella also include multiple hemorrhage (including intracranial hemorrhage, hemorrhagic gastritis, hemorrhagic pulmonary edema, splenic rupture, adrenal hemorrhage, cystorrhagia and hyphema), encephalitis, pneumonia and abdominal pain [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

Intense abdominal pain is often an early symptom of dissemination, which reveals that multi-system organs are involved, such as the stomach, intestines and spleen (which may lead to hemorrhagic gastritis, intestinal obstruction and splenic rupture) [12, 14, 21]. Abdominal pain usually presents earlier before the appearance of the rash with a mean interval of 6.5 days [9, 20, 22]. Visceral VZV infection often presents as epigastric abdominal pain, occasionally involving the right upper quadrant or radiating to the back [23].The patient in our case began with abdominal pain and was initially diagnosed with intestinal obstruction, which led to schedule an emergency laparotomy. Thrombocytopenia and DIC was observed, which may have lead to the occurrence of gastrorrhagia, cystorrhagia and finally hemorrhagic shock. A review of 270 patients with varicella infection found that thrombocytopenia was very common, with 30% of patients having a platelet count < 150 × 109/L [24]. Although our patient did not have purpura, purpura is often a sign of thrombocytopenia. The estimated incidence of thrombocytopenic purpura as a complication of varicella infection is approximately 1:25,000 [25]. In addition, varicella is frequently accompanied by some degree of DIC, particularly in immunocompromised patients [26].

VZV is usually confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified VZV DNA and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) detection of anti-VZV antibody [27]. In our case, we applied a novel method, referred to as next-generation sequencing (NGS). As a complementary method to conventional methods of diagnosis such as viral isolation in cell culture, viral detection by molecular testing and genetic analysis by cycle sequencing, NGS provides a powerful tool to address the challenges of viral infections, which has been applied to a metagenomics-based strategy for rapid and accurate discovery and characterization of new viruses and detection of unexpected viral pathogens in clinical specimens [28].

The patient with SLE in our case was just discharged from the Department of Dermatology, where she had many opportunities for exposure to patients with herpes zoster or varicella. And the patient had never been vaccinated against varicella before. Vaccination of close contacts should be considered for immunocompetent individuals [29]. However, for immunocompromised individuals, VZV vaccination is contraindicated and can be fatal because the vaccine contains live attenuated virus. In case of exposure, medical care should be sought immediately as varicella-zoster immune globulin (VariZig) may be effective in reducing disease severity and should be administered as soon as possible after exposure [30]. However, VariZig is not available in China up to now because it has not been licensed. As clinicians, once virus infection of immunocompromised patients is observed or considered, antiviral therapies should been initiated along with supportive treatment as soon as possible so that the patients can have a slim chance of survival.

Availability of data and materials

All data contained within the article.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DIC:

-

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- SLE:

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- VariZig:

-

Varicella-zoster immune globulin

- VZV:

-

Varicella-zoster virus

References

Akiyama M, Kobayashi N, Fujisawa K, Eto Y. Disseminated varicella-zoster virus infection in a girl with T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(7):716.

Wu CT, Tsai SC, Lin JJ, Hsia SH. Disseminated varicella infection in a child receiving short-term steroids for asthma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25(4):484–6.

Rommelaere M, Marechal C, Yombi JC, Goffin E, Kanaan N. Disseminated varicella zoster virus infection in adult renal transplant recipients: outcome and risk factors. Transplant Proc. 2012;44(9):2814–7.

Schiller GJ, Nimer SD, Gajewski JL, Golde DW. Abdominal presentation of varicella-zoster infection in recipients of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1991;7(6):489–91.

Mpaka M, Karantanas AH, Zakynthinos E. Atypical presentation of varicella-zoster virus encephalitis in an immunocompetent adult. Heart Lung. 2008;37(1):61–6.

Beby-Defaux A, Brabant S, Chatellier D, Bourgoin A, Robert R, Ruckes T, et al. Disseminated varicella with multiorgan failure in an immunocompetent adult. J Med Virol. 2009;81(4):747–9.

Grant RM, Weitzman SS, Sherman CG, Sirkin WL, Petric M, Tellier R. Fulminant disseminated varicella zoster virus infection without skin involvement. J Clin Virol. 2002;24(1–2):7–12.

Kole AK, Roy R, Kole DC. An observational study of complications in chickenpox with special reference to unusual complications in an apex infectious disease hospital, Kolkata, India. J Postgrad Med. 2013;59(2):93–7.

Tsuji H, Yoshifuji H, Fujii T, Matsuo T, Nakashima R, Imura Y, et al. Visceral disseminated varicella zoster virus infection after rituximab treatment for granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2017;27(1):155–61.

Muller I, Aepinus C, Beck R, Bultmann B, Niethammer D, Klingebiel T. Noncutaneous varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection with fatal liver failure in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;37(2):145–7.

Matsuo K, Uozumi Y, Miyamoto H, Tatsumi S, Kohmura E. Varicella-zoster vasculitis presenting with cerebellar hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24(6):e153–5.

Serris A, Michot JM, Fourn E, Le Bras P, Dollat M, Hirsch G, et al. Disseminated varicella-zoster virus infection with hemorrhagic gastritis during the course of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: case report and literature review. Rev Med Interne. 2014;35(5):337–40.

Martin Ibanez I, Diaz Gonzalez EP, Rodriguez Miguelez JM, Figueras AJ. Neonatal varicella: report of a case of bronchopneumonia and hemorrhagic pulmonary edema. An Esp Pediatr. 2001;55(1):58–60.

Uthayakumar A, Harrington D. Spontaneous splenic rupture complicating primary varicella zoster infection: a case report. BMC Res notes. 2018;11(1):334.

Heitz AFN, Hofstee HMA, Gelinck LBS, Puylaert JB. A rare case of Waterhouse- Friderichsen syndrome during primary varicella zoster infection. Neth J Med. 2017;75(8):351–3.

Amar AD. Hematuria caused by varicella lesions in the bladder. Jama. 1966;196(5):450.

Hosogai M, Nakatani Y, Mimura K, Kishi S, Akiyama H. Genetic analysis of varicella-zoster virus in the aqueous humor in uveitis with severe hyphema. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):427.

Chai W, Ho MG. Disseminated varicella zoster virus encephalitis. Lancet. 2014;384(9955):1698.

Umstattd LJ, Reichenberg JS. Varicella pneumonia with immune thrombocytopenic purpura: a patient with multiple complications. Cutis. 2008;82(6):399–402.

Balkis MM, Ghosn S, Sharara AI, Atweh SF, Kanj SS. Disseminated varicella presenting as acute abdominal pain nine days before the appearance of the rash. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(3):e93–5.

Chang AE, Young NA, Reddick RL, Orenstein JM, Hosea SW, Katz P, et al. Small bowel obstruction as a complication of disseminated varicella-zoster infection. Surgery. 1978;83(4):371–4.

Ohara F, Kobayashi Y, Akabane D, Maruyama D, Tanimoto K, Kim SW, et al. Abdominal pain and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion as a manifestation of visceral varicella zoster virus infection in a patient with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2007;82(5):416.

David DS, Tegtmeier BR, O'Donnell MR, Paz IB, McCarty TM. Visceral varicella-zoster after bone marrow transplantation: report of a case series and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(5):810–3.

Ali N, Anwar M, Majeed I, Tariq WU. Chicken pox associated thrombocytopenia in adults. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2006;16(4):270–2.

Amir A, Gilad O, Yacobovich J, Scheuerman O, Tamary H, Garty BZ. Post-varicella thrombocytopenic purpura. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99(9):1385–8.

Hollenstein U, Thalhammer F, Burgmann H. Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and rhabdomyolysis in fulminant varicella infection--case report and review of the literature. Infection. 1998;26(5):306–8.

Sauerbrei A. Diagnosis, antiviral therapy, and prophylaxis of varicella-zoster virus infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35(5):723–34.

Barzon L, Lavezzo E, Militello V, Toppo S, Palu G. Applications of next-generation sequencing technologies to diagnostic virology. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12(11):7861–84.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended adult immunization schedule-United States, 2012. MMWR. 2012;61:1–7.

American Academy of Pediatrics. In: Pickering LK, editor. Red Book: 2003 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 26th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2003. p. 672–86.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This case report is funded by Shanghai Sailing Program 18YF1402800. The funding is used for language editing and publishing fees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WZ drafted the manuscript, QLR, YF and YKH revised the manuscript. All authors were involved in the care of the patient. WZ, QLR, YF and YKH performed the NGS diagnosis and associated testing. All authors made important contributions and have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We identified this patient during routine clinical practice and consented to give venous blood samples after elaborate information. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents for publication of this case report and the accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review. Involvement of the ethical committee of the Huashan Hospital of Fudan University was considered unnecessary, since the project was not based on a study protocol.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents for publication of this case report and the accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, W., Ruan, Ql., Yan, F. et al. Fatal hemorrhagic varicella in a patient with abdominal pain: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 20, 54 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4716-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4716-6