Abstract

Background

Primary varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection is a common illness, predominantly affecting children. Its course is typically benign, although severe complications have been described. Splenic rupture is an extremely rare and potentially fatal complication of primary VZV infection, with only a handful of cases reported in the literature.

Case Presentation

A 32-year-old Romanian man with no significant past medical history, presented with a 2 day history of sudden onset, worsening generalised abdominal pain and a 1 day history of vomiting. The following day he developed fevers and a generalised widespread erythematous rash consisting of clusters of macules, papules and vesicles at different stages of development. There was no history of sore throat, coryza, arthralgia, myalgia, cough, shortness of breath, weight loss, or night sweats. There was no recent illness and no history of trauma. CT abdomen showed splenic rupture with intra-abdominal haemorrhage. Admission bloods showed anaemia and thrombocytopenia, with haemoglobin 110 g/l and platelets 78 × 109/l. Viral PCR of vesicle fluid from the rash was positive for VZV DNA confirming the clinical diagnosis of primary varicella zoster infection. Viral serology also confirmed recent infection. He was haemodynamically resuscitated, and underwent laparotomy and splenectomy. He was commenced on IV acyclovir and completed a 5 day course. Prior to discharge he was commenced on recommended splenectomy secondary prevention treatment.

Conclusion

There are several reported complications of varicella infection, more commonly in the immunocompromised population. Spontaneous splenic rupture is an unusual complication of primary VZV infection. Here we report the sixth known case in the literature. Splenic rupture should be considered in cases of primary varicella in young adults presenting with abdominal pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Primary varicella zoster virus (VZV) is a ubiquitous virus of the family herpesviridae. Infection is typically seen in childhood, and typically follows a benign, self-limiting course. It is highly infectious, spread by close contact or respiratory droplets, with the secondary infection rate from a household contact of chickenpox as high as 90% [1].

This case highlights a potentially life threatening complication of a common infection caused by an ubiquitous virus, which may easily be missed if not considered. It is the 6th report of this complication developing secondary to VZV, which infects approximately 90% of people by adulthood.

Case presentation

A 32-year-old Romanian man presented with a 2 day history of sudden onset, worsening generalised abdominal pain and a 1 day history of vomiting. On the day after admission he developed fevers and a generalised rash which was neither itchy nor painful. There was no history of sore throat, coryza, arthralgia, myalgia, cough, shortness of breath, weight loss, or night sweats. There was no recent illness and no history of trauma.

There was no significant past medical history or previous surgery. He had no known history of chickenpox. He took no medications of any kind. He was a heavy smoker, and reported minimal alcohol intake. He was originally from Romania, and had lived in the UK for 7 months. He had no other travel history. He lived alone and had one regular female sexual partner for the past 3 months.

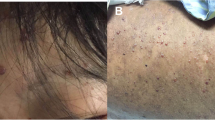

On examination he was alert and comfortable. His pulse was 110 bpm, blood pressure 145/100 mmHg, respiratory rate 24/min, temperature 37.2 °C, oxygen saturations 97% on room air. He had a widespread erythematous rash consisting of clusters of macules, papules and vesicles at different stages of development, worse on upper limbs, torso, and back. The chest was clear to auscultation and the abdomen was generally tender, with a palpable enlarged spleen. There was no guarding or percussion tenderness. Neurological examination was normal.

Admission bloods (see Table 1) showed haemoglobin (Hb) 110 g/l, white cell count (WCC) 3.6 × 109/l, with lymphocyte count of 0.6 × 109/l, platelets 78 × 109/l. C-reactive protein (CRP) was 59 mg/l. Clotting screen, renal function, liver function and amylase were normal. Hepatitis B surface antigen hepatitis C antibody, and HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) 1 and 2 antibody tests were negative. Epstein barr virus (EBV) serology was viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgM negative, VCA IgG negative, and Epstein Barr Nuclear Antigen (EBNA) IgG positive, consistent with infection more than 8 weeks previously. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgG was positive, and CMV IgM negative, consistent with previous infection. Serum VZV IgM was negative, serum VZV IgG equivocal (value 0.65 mIU/ml; reference range-negative < 0.65 mIU/ml, equivocal 0.65–0.9 mIU/ml, positive > 0.9 mIU/ml), and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of vesicle fluid from the rash was positive for VZV DNA and negative for herpes simplex virus (HSV) DNA, confirming the clinical diagnosis of primary varicella zoster infection.

Subsequent CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed a splenic rupture of an enlarged spleen (18 cm diameter) with visible capsular haematoma, and extensive high density intra-abdominal free fluid surrounding the spleen and liver, in keeping with haemorrhage (see Fig. 1). The bowel, liver, biliary system, adrenals, pancreas, kidneys and bladder were normal. An ultrasound guided aspiration of the free intra-abdominal fluid revealed frank blood. Subsequent CT angiogram did not identify a bleeding point and illustrated stable appearances of intra-abdominal free fluid.

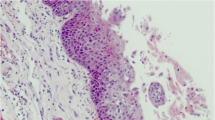

IV acyclovir 10 mg/kg, 8-hourly and oral co-amoxiclav 625 mg 8-hourly were started on admission. Two units of packed red cells and one pool of platelets were transfused alongside IV 0.9% sodium chloride solution, before undergoing laparotomy and splenectomy on day two of the admission. Surgical findings were of gross peritoneal blood, and ruptured splenic capsule with large adherent haematoma. Histological analysis of the spleen showed normal tissue, with no evidence of amyloid, haematological malignancy or EBV.

He remained alert and haemodynamically stable throughout the perioperative period. He improved clinically and biochemically, with normalisation of the thrombocytopenia and lymphopenia seen on admission. His rash significantly improved, with only a small number of crusted vesicles still present at time of discharge. Co-amoxiclav was stopped after laboratory confirmation of the diagnosis; IV acyclovir was changed to an oral formulation after 4 days, with 5 days acyclovir being given in total. Lifelong prophylactic penicillin V was commenced before discharge, with early follow up booked to administer meningococcus ACWY, conjugate pneumococcus, haemophilus influenzae B, and seasonal influenza vaccines.

He remained well at follow up, with no sign of on-going or recurrent disease.

Discussion and conclusions

Primary VZV infection causes chickenpox, which is characterised by a prodrome of fever and malaise, which may be absent, followed by a widespread vesicular rash which typically starts on the face and scalp before spreading to the torso and back, and then the limbs. Lesions may be sparse or numerous, and are seen in different stages of development. The infectious period is 2 days before the onset of the rash, and the patient is non-infectious when all lesions have crusted over. Latency is then established in the sensory ganglia, and may reactivate as shingles in later life. Seropositivity is seen in up to 90% of adults [1].

Severe complications are described, and infections can be more serious in the adult or immunocompromised population. Secondary bacterial infections, pneumonitis, meningoencephalitis are well described and are associated with high mortality and morbidity [2]. Cerebellar ataxia is the commonest neurological complication and carries a good prognosis [2]. Transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, thrombocytopenia, haemorrhagic varicella, purpura fulminans, glomerulonephritis, myocarditis, arthritis, orchitis, uveitis, iritis, and hepatitis have also been rarely described [2]. Splenic rupture is an extremely rare complication of primary VZV infection with only a handful of cases reported in the literature. Splenic rupture is more commonly associated with other herpesviridae, notably in glandular fever (infectious mononucleosis) caused by Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), where it complicates 0.1–0.5% of cases [3], and is typically seen in young adults, most frequently men. Splenomegaly and capsular thinning increases the risk of rupture, which may be due to minimal trauma, or occur spontaneously [4]. Other causes of non-traumatic spontaneous splenic rupture include haematological abnormalities such as lymphoma and myelofibrosis, amyloidosis, and other infections including malaria. Spontaneous splenic rupture has a mortality of 12.2% [5], and may require urgent surgical or radiological intervention. In the setting of EBV infection estimates of mortality of spontaneous splenic rupture are between 30 and 100% [6].

Splenomegaly [7], and increased uptake in the spleen seen on Positron emission tomography- computed tomography (PET-CT) [8], has been described in primary VZV infection. Macroscopic splenic nodularity is also described in the setting of primary VZV infection [9]. However, there are only five reports of splenic rupture occurring in the setting of primary VZV infection [9,10,11,12,13]. All cases are reported in young, adult males, as with our case [9,10,11,12,13]. In all cases, abdominal pain preceded the onset of rash, and in all cases but one [9], there was no haemodynamic compromise. The case we present is consistent with these reports, with abdominal pain, likely representing splenic rupture itself, preceding the rash by 48 h. Haemodynamic instability was not present, as with four of the five published reports. Splenomegaly was present as would be expected with a spontaneous splenic rupture, although there is one case in the literature which reported splenic rupture of a normal sized spleen [12]. There was no history of even minimal trauma, as with previous reports.

Spontaneous splenic rupture is an unusual complication of primary VZV infection. Here we report the sixth known case in the literature. Splenic rupture should be considered in cases of primary varicella in young adults presenting with abdominal pain.

Abbreviations

- VZV:

-

varicella zoster virus

- HIV:

-

human immunodeficiency virus

- EBV:

-

Epstein Barr Virus

- VCA:

-

viral capsid antigen

- EBNA:

-

Epstein Barr Nuclear Antigen

- CMV:

-

cytomegalovirus

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- HSV:

-

herpes simplex virus

- PET-CT:

-

positron emission tomography-computed tomography

References

Public Health England (PHE). The green book, Chapter 34: Varicella. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/varicella-the-green-book-chapter-34. Accessed 13 Feb 2017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The pink book, Chapter 22: Varicella. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/varicella.html. Accessed 13 Feb 2017.

Chapman AL, Watkin R, Ellis CJ. Abdominal pain in acute infectious mononucleosis. BMJ. 2002;324:660–1.

Schuler JG, Filtzer H. Spontaneous splenic rupture. The role of non-operative management. Arch Surg. 1995;130:662–5.

Renzulli P, Hostettler A, Schoepfer A, Gloor B, Candinas D. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br J Surg. 2009;96(10):1114–21.

Rothwell S, McAuley D. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Emerg Med. 2001;13:364–6.

Higgins PM. Splenomegaly in acute infections due to group A Streptococci and viruses. Epidemiol Infect. 1992;109:199–209.

Sheehy N, Israel DA. Acute varicella infection mimics recurrent Hodgkin’s disease on F-18 FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2007;32(10):820–1.

Tapp E. Ruptured spleen associated with chicken-pox. BMJ. 1969;1(5644):617–8.

Clifton LJ, Dhaliwal KS, Saif D, Mullerat P. Varicella zoster virus infection is an unusual case of splenic rupture. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2015-210909.

Ul Yaqin H. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in the prodromal period of chickenpox. Postgrad Med J. 1969;45(519):51–3.

Vial I, Hamidou M, Coste-Burel M, Baron D. Abdominal pain in varicella: an unusual case of spontaneous splenic rupture. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:176–7.

Harris RA, Boland SL. Varicella zoster associated with spontaneous splenic rupture. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68(2):162–3.

Authors’ contributions

Both DH and AU were doctors within the medical team responsible for the care of the patient. AU was responsible for data collection including patient notes, lab results and imaging. AU wrote the case description. DH was also responsible for the analysis and discussion within the case report. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All results available included in figures and tables.

Consent for publication

Patient has given written consent for publication of information and images.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

There were no funding sources.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Uthayakumar, A., Harrington, D. Spontaneous splenic rupture complicating primary varicella zoster infection: a case report. BMC Res Notes 11, 334 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3430-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3430-6