Abstract

Background

Pain, neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) and functional impairment are prevalent in patients with dementia and pain is hypothesized to be causal in both neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) and functional impairment. As the exact nature of the associations is unknown, this review examines the strength of associations between pain and NPS, and pain and physical function in patients with dementia. Special attention is paid to the description of measurement instruments and the methods used to detect pain, NPS and physical function.

Methods

A systematic search was made in the databases of PubMed (Medline), Embase, Cochrane, Cinahl, PsychINFO, and Web of Science. Studies were included that described associations between pain and NPS and/or physical function in patients with moderate to severe dementia.

Results

The search yielded 22 articles describing 18 studies, including two longitudinal studies. Most evidence was found for the association between pain and depression, followed by the association between pain and agitation/aggression. The longitudinal studies reported no direct effects between pain and NPS but some indirect effects, e.g. pain through depression. Although some association was established between pain and NPS, and pain and physical function, the strength of associations was relatively weak. Interestingly, only three studies used an observer rating scale for pain-related behaviour.

Conclusions

Available evidence does not support strong associations between pain, NPS and physical function. This might be due to inadequate use or lack of rating scales to detect pain-related behaviour. These results show that the relationship between pain and NPS, as well as with physical function, is complicated and warrants additional longitudinal evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pain is common among older persons due to the increased prevalence of age-related diseases like osteoporosis and arthritis [1]. This also applies to patients with dementia living in nursing homes: around 50% is in pain [2,3].

Due to the changed perception of pain and loss of language skills in dementia, pain is often not communicated as such. In these patients, pain is often reported to be expressed as challenging behaviour (e.g. agitation or withdrawal) and is also known as neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) [4-6]. NPS includes depressive symptoms, agitated/aggressive behaviour, and psychotic symptoms like hallucinations and delusions [7].

NPS is highly prevalent: up to 80-85% of patients with dementia experience these symptoms [7-9] and they are one of the main reasons for institutionalisation [9,10]. The aetiology of NPS is multifactorial and includes neuropathological changes in the brain related to dementia and dementia severity, as well as unmet physical and psychological needs, physical illness (e.g. urinary tract infections), and pain [11].

Furthermore, pain influences the patient’s physical function, including sleep, nutrition, and mobility [12-15]. Therefore, physical inactivity and disability in patients with dementia may be an expression of pain, but can also be the cause of pain [16,17]. This illustrates that, due to its diverse presentation, the interpretation of potential signs and symptoms of pain in dementia is difficult; moreover, to date, most studies still report a systematic under-recognition and under-treatment of pain [18-20]. There is evidence for specific pain-related behaviour, such as increased wandering or irritability, but facial expressions, body movements, and vocalizations are also common [21]. These behaviours can help in the clinical decision-making process [22]. Consequently, in the last decades, measurement and assessment of pain in patients with dementia by means of observations of these behaviours have received increasing attention. However, clinicians still have insufficient tools to face the challenges in the diagnostics and treatment of pain in this vulnerable group, [22,23] and this may result in clinical indecisiveness. Nevertheless, there are validated measurement instruments available to detect pain in patients with dementia, such as the PACSLAC, DOLOPLUS-2, and the MOBID-2, based on observations [24,25]. Adequate use of these measurement instruments is of utmost importance in the management of pain.

Due to the challenges in the assessment and management of pain [26], people with dementia and NPS are more likely to receive antipsychotic drugs, despite the adverse side-effects like falls, somnolence and even death [27-29]. The latter underlines the importance of understanding the attributive effect of pain as a cause of NPS and decline in physical function. This would give healthcare workers more insight as to whether to target their treatment primarily on pain, NPS, disability, or on these conditions simultaneously.

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to assess the strength of associations between pain and NPS, and between pain and physical function, in patients with dementia. Special attention is paid to the description of measurement instruments and the method of detecting pain, NPS, and physical function to give clinical and scientific direction to the assessment and treatment of pain.

Methods

Study selection

This review was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews [30]. A systematic search of the following databases was performed in March 2013: PubMed (Medline), Embase, Cochrane, Cinahl, PsychINFO, and Web of Science. In addition, the reference lists of the retrieved articles were screened. The following search terms (Additional file 1) were applied: Dementia AND Pain AND ((depression) OR (BPSD) OR (mobility) OR (sleep) OR (eating) OR (ADL)). Two reviewers, AvD and MP, independently, screened each title and abstract for suitability for inclusion; they decided independently on the eligibility of the article according to the predetermined selection criteria. Disagreement was resolved by consensus after review of the full article, or after the input of a third author (WA/MdW).

Articles that met the following criteria were included: patients with moderate to severe dementia (defined as a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of ≤18 or a Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) score of 5–7 [31]), description of data on pain, description of NPS, and/or physical function [eating, sleep, activities of daily living (ADL) and mobility]. For the purpose of this review, articles that described patients with mild to moderate dementia, but reported statistical data separately for the subgroup ‘moderate dementia’, were also included.

Eligible study designs included clinical trials, cohort, cross-sectional, observational, and longitudinal studies. Unless there was a clear description of the original data and baseline statistics, systematic reviews, qualitative studies, study protocols, (editorial) letters, case reports and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were excluded. However, the reference lists of these articles were screened for eligible studies that were missed during the initial search. Only published data was included.

Excluded were articles that described patients who suffer from dementia resulting from Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease, AIDS dementia complex, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob Syndrome. Furthermore, we excluded articles that did not report correlation coefficients or odds ratio’s (OR), or when the articles did not provide sufficient information to calculate the OR ourselves. No time range or language restrictions were used.

Data extraction

Data were independently extracted by two reviewers (AvD and MP). A data extraction form was designed before extracting data from the included articles.

We recorded data on: study characteristics (design, country, setting, study population), pain and NPS measurement, prevalence of pain, and correlations of pain, NPS, and physical function. Where possible we present unadjusted associations, as these reflect the presence of co-occurrence as perceived by the caregivers. In addition we calculated the OR ourselves if not reported. These ORs are reported as self-calculated odds ratio (SOR).

Furthermore, we recorded data on the use of rating scales to measure pain, NPS and physical function, as well as the method of detection. For example, if pain was measured with a rating scale for observational behaviours indicating pain and who performed the observation, i.e. a research nurse, a professional or patient’s proxy.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality assessment of the included cross-sectional and longitudinal studies was based on previously developed checklists [32,33]. Two reviewers (AvD and MP) independently assessed the quality of each study. Disagreement was resolved by consensus or after input of a third author (MdW/WA). The maximum total score possible for cross-sectional studies was 12 points and for longitudinal studies 14 points. Cross-sectional studies that scored 0–4 points were considered to be of ‘low quality’, scores of 5–9 to be of ‘moderate quality’, and scores of ≥10 points were considered to be of ‘high quality’. For longitudinal studies, scores of 0–5 points were considered to be of ‘low quality’, scores of 6–11 points to be of ‘moderate quality’, and scores of ≥12 points were considered to be of ‘high quality’. See Additional file 2 for a more detailed overview of the awarded points and scores to the articles.

Scoring items

We selected items relevant for the assessment of observational studies, such as a description of a clearly stated objective, use of valid selection criteria, a response rate of ≥80%, valid/reproducible measurement of the outcome, adjusting for possible confounders, and the presentation of an association. One point was awarded for each questions answered with ‘yes’ and 0 points for every ‘no’ or ‘?’. We added two questions concerning the study objective and population: i) was the selected objective similar to our objective, and ii) was the study population a selected population.

Furthermore, we wanted the quality assessment to reflect the ability to study our research objective. Therefore, we added a few items focusing on the measurement of pain, i.e. the use of specific rating scales, the method of detection, and information about the rater. Awarded points ranged from 0–2.

Additionally, two questions were added to the quality assessment for the longitudinal studies: i) was there major and selective loss to follow-up, and ii) was there a sufficiently long follow-up period [32,33]. Again, 1 point was awarded for each questions answered with ‘yes’ and 0 points for each ‘no’ or ‘?’.

Statistical analysis

To provide a more comprehensive overview of the association between pain, NPS and physical function, the available ORs are displayed in forest plots (using the program Review Manager 5.2) including the pooled ORs using a random effects model.

Results

Selected articles

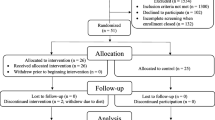

The literature search yielded 1386 articles; 786 from PubMed (Medline), 304 from Embase, 77 from Cinahl, 57 from PsychINFO, 96 from Cochrane, and 66 from Web of Science. Additionally, 22 articles were retrieved from other sources (mainly through checking the reference lists). After removing duplicates, 1091 unique articles were identified. After carefully screening the titles, abstracts and full text, 22 publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in the present review (Figure 1).

Description of included studies

All included articles were published between 2002 and 2013.

Of these 22 articles, eight articles illustrate correlates of pain with specified behavioural problems such as delusions/psychosis [3,34], anxiety [35], wandering [3,36], and resistance to care [3,37,38]. Furthermore, seven articles described associations between pain and unspecified behavioural problems, such as behavioural/psychiatric problems and dysfunctional behaviours [3,4,39-43]. It was not clarified which types of NPS were embedded in this term.

Eleven articles described the association between pain and depression [4,8,34,35,43-49] and eight articles between pain and aggression/agitation [8,34,36,38,47,48,50,51] In addition, relationships between pain and physical function (e.g. ADL dependency and mobility) were described in ten articles [3,4,39,40,43,44,46,48,49,52]. The characteristics of these articles are presented in Table 1.

Most of the studies described patients aged ≥ 65 years, who were mainly diagnosed with moderate to severe dementia and resided in long-term care facilities throughout the USA [4,8,34,36,39-43,45,47,48,50]. Three studies took place in Europe [3,51-53], three studies in Canada [38,44,49], and two studies took place in Asia [35,46].

Of the 20 cross-sectional studies, five studies were considered to be of high quality [3,36,37,43,46]. The remaining 15 studies were of low to moderate quality. Of the two longitudinal studies, that of Volicer et al. was considered to be of high quality [51] (Table 1).

Five studies described the use of selection criteria, mostly on NPS, and in eight other studies there might have been an indirect (unintentional) selection on pain, NPS or functioning. For instance, an indirect selection on pain by including patients with pressure ulcers [8].

Eight articles described the same study populations, sometimes with additional selection criteria, e. g. the two articles by Cipher et al. [4,41]. Kunik et al. and Morgan et al. used data from a large longitudinal study on the causes and consequences of aggression in persons with dementia. Another two articles extracted data from the Dementia Care project of the Collaborative Studies of Long-Term Care [43,45] and two articles derived their data from the same Minimum Dataset 2.0 for nursing home care [37,51].

Overview of measurement instruments

Table 2 describes how pain, NPS, and physical function were measured.

Measurement of pain

Three articles describe rating scales for observational behaviours indicating pain; both scales are validated for patients with moderate to severe dementia, i.e. the PAINAD [35,46] and DS-DAT [38]. The remaining articles describe other methods to measure pain (Additional file 3); some articles used the MDS dataset [3,36,37,50,51] and others used a variety of rating scales, e.g. the Faces Pain Scale [40], the Geriatric Multidimensional Pain and Illness Inventory [4,41], the Proxy Pain Questionnaire [52] and the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Pain Intensity Scale [34,43,45,47]. The Verbal Descriptive Scale and Verbal Rating Scale were also used to measure pain, sometimes combined with self-report [48,49,52]. Three articles used no rating scales to measure pain; they extracted data form patient’s medical records [8,44] and interviewed patient’s proxy and/or healthcare worker [39].

Additional file 3 provides a complete overview of the methods used.

Measurement of NPS

There was no uniform way of reporting NPS. The terms ‘behavioural symptoms’, ‘psychiatric symptoms’, and ‘disruptive behaviour’ were commonly used to describe any type of behavioural symptoms, e.g. agitation, depression, and anxiety [3,4,39-41].

The most common type of reported NPS was depression, followed by symptoms such as wandering, resistance to care, and verbal or physical abuse [36,37,42]. Four articles used no rating scales to measure NPS; they screened medical records instead [8,39,44,46]. Nine articles used more than one rating scale simultaneously to asses NPS [4,34,35,42,43,45,47,49,50]. Eight of those articles used rating scales to assess behaviour in patients with dementia; the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia [43,45], the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory [34,43,45,47,49], Behavioural Pathology in Alzheimer’s disease [42], and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory [34] (Table 2). One article used the Mental Health screening questionnaire to assess depressed mood [49]. The MDS Dataset was also frequently used [8,36,37,50,51].

Measurement of Physical Function

Physical function was described in eleven articles [3,4,39,40,43-46,48,49,52].

Types of physical function that were reported in the articles are malnourishment [39,43,45], ADL dependency [3,4,40,43,49,52], and mobility [43,44,46].

Five articles used the MDS-ADL scale for measuring patient’s physical function (Table 2). This was also the most frequently used measurement [3,8,36,43-45].

Associations between pain, NPS and physical function

Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6 describe the associations between pain, NPS, and physical function.

In total we found 81 associations expressed in either ORs or correlations. The prevalence rates of pain, NPS, and impairment of physical function ranged from 19-72% [3,4], 2-85% [37,39] and 12-92%, respectively [40,43,45].

Of the 22 included articles, the ORs could be extracted in six and the correlation coefficient in nine articles; in addition, we could calculate the SOR for the associations in ten articles.

Pain and neuropsychiatric symptoms

The most commonly described associations were between pain and depression (Table 3), pain and agitation (Table 4), and pain and specified NPS (Table 5), such as a negative association between pain and wandering, resistance to care, physical and verbal abuse, and aberrant vocalizations [3,36-38].

Eleven articles described associations between pain and depression (Table 3); in seven of these there was a positive association, with three articles reporting a strong association with an OR >3 or = 0.5. In four articles the association was not significant: one article did not use a rating scale but examined medical records, one article used the rating scale PAINAD to measure pain, one article measured pain by observations, and another article used self-report. Remarkably, in the study by Shega et al. the OR for pain and depression was lower when pain was rated by the caregiver compared to the self-report of pain: OR 0.47 (95% CI: 0.20-1.14) and OR 1.52 (95% CI: 0.63-3.68), respectively [48]. We could include seven articles in the meta-analysis (see Figure 2) and the pooled OR for pain and depression was 1.84 (95% CI 1.23-2.80).

Eight articles described cross-sectional associations between pain and agitation/aggression (Table 4): four found positive associations, one found a negative association, two found no association, and one study found no association with pain self-report but a positive association with caregiver pain report. The strongest correlation found was in the study by Zieber et al., i.e. r = 0.51 (p < 0.01) between the DS-DAT scores and agitation.

Interestingly, two articles reported on longitudinal changes with follow-up data. In veterans living at home without aggressive behaviour in the preceding year or in the first five months of follow-up, Morgan et al. found that depression indirectly predicted the onset of aggression through pain [47]. In an unselected population Volicer et al. found that changes in agitation scores were related to changes in depression score but not to pain [51].

Furthermore, in a subsample of patients with moderate dementia without the use of psychotropic medication, the association between pain and agitation/aggression was similar compared to residents who used psychotropic drugs [36]. Only two articles could be incorporated in the meta-analysis (see Figure 3) resulting in a pooled OR of 0.95 (95% CI 0.67-1.34).

Table 5 describes NPS, other than depression and agitation/aggression. Relations between pain and anxiety, hallucinations and delusions, were rarely studied. Only one article described an association between pain and anxiety, which was positive: SOR 1.8 (95% CI 1.0-3.0) [35]. Two articles described psychosis and delusions as being related to pain [3,34]. Kunik et al. found a small but non-significant association (r = 0.15; p >0.05) with psychosis and Tosato et al. found an OR of 1.5 (95% CI 1.07-2.03) between pain and delusions.

Furthermore, terms like ‘behavioural/psychiatric problems’ and ‘disruptive behaviour’ were also frequently used to describe unspecified NPS (Table 5). Two out of seven articles reported moderate positive associations, with r = 0.22 (p <0.05) as the strongest correlation between pain and dysfunctional behaviour [4].

Pain and physical function

Eleven articles reported associations between pain and physical function, although in most cases this was not the main topic of the study (Table 6). We found associations between pain and ADL or iADL impairment [3,4,40,48,49,52]. One article reported a positive association between pain and iADL impairment: OR 1.74 (95% CI 1.15-2.62) [49]. Other associations (although not significant) with physical impairment described in the articles were immobility [44,46] and malnourishment [43].

Only two articles described a positive association: one study used the PAINAD to objectify pain and one study used a five-point verbal descriptive scale to measure pain and a three-point scale (OARS/IADL) to measure functional impairment [46,49].

The strongest reported association was with assisted transfer compared to self-transfer; however, this had a very broad confidence interval: OR 29.7 (95% CI 3.6-242) [46]. The remaining eight articles reported associations which were not significant. Based on five articles, the pooled OR (see Figure 4) for pain and overall physical function was 1.01 (95% CI 0.85-1.20).

Discussion

Despite the increased attention for pain in dementia, relatively few studies have explored associations between pain and NPS, and pain and physical function. We found 22 articles reporting the strength of associations between these three modalities, including only two longitudinal studies.

We found most evidence for the association between pain and depression (in 7 of 11 articles), followed by the association between pain and agitation/aggression (in 5 of 8 articles). The two longitudinal studies reported no direct effects between pain and NPS but only some indirect effects, e.g. of pain through depression. Interestingly, articles reporting a significant positive association between pain and NPS, and between pain and physical function, were mainly of low methodological quality. One article with high methodological quality reported a non-significant correlation between pain frequency and verbal abuse [37]. Four high-quality articles reported a positive association between pain, aggression/agitation and wandering [36,51], between pain and functional impairment [46], and between pain and behavioural symptoms [43].

Due to the hypothesized effect of pain on NPS and physical function, and some overlap of items in the measurement instruments, we expected to find stronger associations; particularly since pain interventions targeting NPS and behavioural interventions targeting pain are reported to reduce both pain and NPS (such as depression and agitation/aggression) [54]. In addition, a cluster RCT by Husebo et al., investigating a sample of moderate to severe dementia patients with challenging behaviour, showed that treating pain led to a significant improvement in mood symptoms such as depression, apathy, and eating disorders, and improvements in ADL function were also found [12]. Furthermore, research among elderly without cognitive impairment shows an association between pain and depression; there is also evidence that treatment of depression in cognitively intact older patients improves pain and physical function [46,55,56]. It is plausible that this also applies to patients with dementia.

However, the associations found in the present systematic review were rather weak. This may be the result of inadequate assessment of both pain and NPS in the included studies. Most studies did not use measurement instruments developed for the assessment of pain in people with dementia. For example, D’Astolfo et al. did not use a measurement instrument for pain or for NPS, but only screened medical records and found relatively weak and non-significant associations. Also, it is possible that healthcare workers interpret NPS as symptoms of either pain or challenging behaviour; if this is the case, then only pain or NPS is reported in the medical records and no association will be found.

Five articles used the MDS-RAI Dataset to measure pain and also reported weak associations [3,36,37,50,51]. These articles also report weak associations. This might be due to the doubt about the accuracy of measuring pain in people suffering from dementia with the MDS-RAI Dataset [57,58].

We hypothesize that validated rating scales, used by a professional, will provide a more accurate reflection of the relationship between pain and NPS. This is illustrated by the study of Zieber et al. in which a clear distinction is seen in the strength of the correlations between pain and agitation when rated by a palliative nurse consultant or when rated by the facility nurse [38]. When rated by the palliative nurse consultant the correlation was stronger: = 0.49 (p < 0.01) compared with the rating by the facility nurse: r = 0.28 (p < 0.05). This also applied to the correlation between pain and aberrant vocalizations: r < 0.40 (p < 0.01) and r = 0.065 (p < 0.63), respectively, but not between pain and resisting care: r < 0.51 (p < 0.01) and r = 0.48 (p < 0.01), respectively. In addition, in a study by Leong et al. a professional used the PAINAD to asses pain and found a SOR of 3.2 (95% CI 1.8-5.9) between pain and depression [35]. However, other studies with a relative strong association between pain and depression did not use professionals or validated rating scales to assess pain in patients with dementia [43,45]. Therefore, the results of the present review cannot fully support the hypothesis of a better reflection of the relationship between pain and NPS when validated rating scales are used by professionals.

Another explanation for the rather weak associations found in this review could be the inclusion of six articles which described individuals with predominantly severe dementia. Together with the progression of dementia, the assessment of pain becomes even more difficult due to diminished pain behaviours [59], but facial expressions tend to increase in the course of dementia [60]. Of the measurement instruments used in the included studies, only the PAINAD and DS-DAT include facial expressions of pain. In addition, in the included studies, the use of antipsychotic drugs could also explain the weak associations. Antipsychotic drugs may distort and diminish the expression of NPS while a possible cause of NPS, for instance pain, is not treated. This may have resulted in the under-recognition and poor report of NPS. However, the study by Ahn et al. shows that, in a subsample of patients without psychotropic drugs, the association between pain and agitation/aggression, and between pain and wandering, was similar to that in residents who used psychotropic drugs [36].

Moreover, we could have anticipated finding rather weak associations, because most of the included studies were cross-sectional in design. This is illustrated by studies that found that a change in pain after an intervention is related to a decrease in NPS or function [61,62].

To some extent the included articles measured overall functional impairment with, for example, total ADL scores. Some articles focused on specific components of physical function, like nutritional status and mobility, which are often hampered in patients with dementia. However, because the focus of these articles was not on the association between pain and physical function, in most cases we had to calculate the association between pain and physical function (SOR) ourselves. This raises the question as to whether physical function is receiving the attention it deserves and, possibly, may even lead to publication bias. Physical inactivity or impairment is an important sign that a patient with dementia could be in pain; this is illustrated by a study in which patients with moderate to severe dementia (treated with acetaminophen) tend to spend more time in social interaction and engage with the environment more actively, than patients who received placebo [62]. Unfortunately, until now, no longitudinal studies are available that describe the course of physical function in patients with dementia in relation to pain.

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first to give a comprehensive and systematic analysis of the associations between pain and NPS, and pain and physical function, in patients with dementia. One of the strengths of this study is that we not only included publications that presented associations between pain and NPS and pain and physical function, but also publications that provide enough information to compute ORs, thus taking full advantage of the available evidence. In addition, when possible, we present the crude OR as this reflects the presence of co-occurrence as perceived by the caregivers. Furthermore, we used a methodological quality assessment based on previously developed checklists [32,33]. By adding extra items focusing on the measurement of pain, study objective and population, we tailored the quality assessment to the purpose of this review. We believe that this strategy has led to a better reflection of the challenges in the assessment of pain and NPS.

A possible limitation could be some publication bias, e.g. if some studies do not report the associations because they were negative. Also, we explicitly searched for publications about pain and not for terms like ‘distress’ or ‘discomfort’. However, we believe that this approach provides the best reflection of the complex relation between pain, NPS and physical function. Furthermore, we were unable to include every study in the meta-analysis due to missing data. In addition, the forest plots should be interpreted with caution, since the included studies are heterogeneous and studies with a large sample size (e.g. studies using the MDS Dataset) were awarded more weight in the meta-analysis; however, this weighting is not necessarily justified because, in observational studies, a larger sample size does not necessarily means that these studies are of good methodological quality. Another possible limitation is that we did not include delirium as a separate search term in our search strategy. However, as delirium is a syndrome with specific neuropsychiatric symptoms, we looked at the clinical features of a delirium by including these symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, in our search strategy.

Clinical implications

The American Geriatrics Society (AGS) published clinical guidance on persistent pain, outlining 26 behavioural expressions of pain in the elderly [21]. The AGS panel advises clinicians to assess pain in older persons with moderate to severe dementia via direct observation of this pain-related behaviour, or via history from caregivers. Several observational scales are available based on the presence of or alterations in behaviours, emotions, interactions, and facial expressions. However, there is little empirical evidence that these 26 behavioural expressions are indeed related to pain. In our review, only depression and agitation/aggression seem to be associated with pain.

The advice of direct observation of pain-related behaviour seems to be poorly implemented, as illustrated by this review, in which only three studies used rating scales based on behavioural observations [35,38,46]. It can be assumed that, when this non-optimal situation exists in a research setting, then routine implementation of rating scales based on behavioural observation in clinical practice will be even less optimal.

The results presented in this review do not fully support the association between pain, NPS and functional impairment in dementia. However, they do highlight the presence of difficulties in the management of pain in dementia. This is illustrated by the frequent use of terms like ‘behavioural symptoms’, ‘disruptive behaviour’, and ‘psychiatric symptoms’. There is no uniform way of reporting neuropsychiatric symptoms; this could complicate the comparison between behavioural symptoms and also reveals the challenges in differentiating between the different, but often very similar, types of challenging behaviour. This also applies to the description of physical function; the specific functions and activities should be properly described (e.g. malnutrition, sleep disturbances, and immobility) and not merely presented as a total ADL score.

Clearly, co-occurrence will not (and can not) be easily observed, probably leading to clinical indecisiveness. However, regardless of co-occurrence, we want to stress the importance of pain detection in patients with dementia because pain can be the cause of other disorders, such as NPS. Moreover, it has been proven that pain treatment significantly reduces behavioural disturbances, such as agitation [12,54,61]. Pain and it’s consequences have an impact on the quality of life and therefore should be recognized, measured and treated.

Conclusions

This review shows, unexpectedly, rather weak associations between pain and NPS, and between pain and physical function. Nevertheless, the relationship between pain and the onset of NPS, as well as the effect on physical function, remains unclear and should be further explored. To unravel this complex relationship, the course of pain, NPS and physical function should be examined longitudinally, using valid measurement instruments. A longitudinal study design will provide more information on causality and the sequence of these modalities, providing evidence that can be incorporated in clinical practice to improve the management of pain for people with dementia.

References

Feldt KS, Warne MA, Ryden MB. Examining pain in aggressive cognitively impaired older adults. J Gerontol Nurs. 1998;24(11):14–22.

Zwakhalen SM, Koopmans RT, Geels PJ, Berger MP, Hamers JP. The prevalence of pain in nursing home residents with dementia measured using an observational pain scale. Eur J Pain. 2009;13(1):89–93.

Tosato M, Lukas A, van der Roest HG, Danese P, Antocicco M, Finne-Soveri H, et al. Association of pain with behavioral and psychiatric symptoms among nursing home residents with cognitive impairment: results from the SHELTER study. Pain. 2012;153(2):305–10.

Cipher DJ, Clifford PA. Dementia, pain, depression, behavioral disturbances, and ADLs: toward a comprehensive conceptualization of quality of life in long-term care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(8):741–8.

Buffum MD, Miaskowski C, Sands L, Brod M. A pilot study of the relationship between discomfort and agitation in patients with dementia. Geriatr Nurs. 2001;22(2):80–5.

Geda YE, Schneider LS, Gitlin LN, Miller DS, Smith GS, Bell J, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: past progress and anticipation of the future. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(5):602–8.

Ballard C, Bannister C, Solis M, Oyebode F, Wilcock G. The prevalence, associations and symptoms of depression amongst dementia sufferers. J Affect Disord. 1996;36(3–4):135–44.

Bartels SJ, Horn SD, Smout RJ, Dums AR, Flaherty E, Jones JK, et al. Agitation and depression in frail nursing home elderly patients with dementia: treatment characteristics and service use. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(2):231–8.

Zuidema S, Koopmans R, Verhey F. Prevalence and predictors of neuropsychiatric symptoms in cognitively impaired nursing home patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2007;20(1):41–9.

Heeren O, Borin L, Raskin A, Gruber-Baldini AL, Menon AS, Kaup B, et al. Association of depression with agitation in elderly nursing home residents. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2003;16(1):4–7.

Lyketsos CG, Colenda CC, Beck C, Blank K, Doraiswamy MP, Kalunian DA, et al. Position statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry regarding principles of care for patients with dementia resulting from Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(7):561–72.

Husebo BS, Ballard C, Fritze F, Sandvik R, Aarsland D. Efficacy of pain treatment on mood syndrome in patients with dementia: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2013;29(2):828–36.

Won A, Lapane K, Gambassi G, Bernabei R, Mor V, Lipsitz LA. Correlates and management of nonmalignant pain in the nursing home. SAGE Study Group. Systematic Assessment of Geriatric drug use via Epidemiology. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(8):936–42.

Beullens J, Schols J. [Treatment of insomnia in demented nursing home patients: a review]. Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr. 2002;33(1):15–20.

Giron MS, Forsell Y, Bernsten C, Thorslund M, Winblad B, Fastbom J. Sleep problems in a very old population: drug use and clinical correlates. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(4):M236–40.

Plooij B, Scherder EJ, Eggermont LH. Physical inactivity in aging and dementia: a review of its relationship to pain. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(21–22):3002–8.

Scherder EJ, Sergeant JA, Swaab DF. Pain processing in dementia and its relation to neuropathology. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2(11):677–86.

Achterberg WP, Scherder E, Pot AM, Ribbe MW. Cardiovascular risk factors in cognitively impaired nursing home patients: a relationship with pain? Eur J Pain. 2007;11(6):707–10.

Nygaard HA, Jarland M. Are nursing home patients with dementia diagnosis at increased risk for inadequate pain treatment? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(8):730–7.

Tait RC, Chibnall JT. Under-Treatment of Pain in Dementia: Assessment is Key. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(6):372–4.

AGS Panel on Persistant Pain in Older Persons. The management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(6 Suppl):S205–24.

Achterberg WP, Pieper MJ, van Dalen-Kok AH, de Waal MW, Husebo BS, Lautenbacher S, et al. Pain management in patients with dementia. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1471–82.

Corbett A, Husebo B, Malcangio M, Staniland A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Aarsland D, et al. Assessment and treatment of pain in people with dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8(5):264–74.

Zwakhalen SM, Hamers JP, Abu-Saad HH, Berger MP. Pain in elderly people with severe dementia: a systematic review of behavioural pain assessment tools. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6:3.

Husebo BS, Ostelo R, Strand LI. The MOBID-2 pain scale: Reliability and responsiveness to pain in patients with dementia. Eur J Pain. 2014;18(10):1490–500.

Husebo BS, Corbett A. Dementia: Pain management in dementia-the value of proxy measures. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(6):313–4.

Briesacher BA, Limcangco MR, Simoni-Wastila L, Doshi JA, Levens SR, Shea DG, et al. The quality of antipsychotic drug prescribing in nursing homes. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(11):1280–5.

Advisory. FPH: Deaths with antipsychotics in elderly patients with with behavioral disturbances. 2005.

Desai VC, Heaton PC, Kelton CM. Impact of the Food and Drug Administration’s antipsychotic black box warning on psychotropic drug prescribing in elderly patients with dementia in outpatient and office-based settings. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(5):453–7.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(9):1136–9.

van der Windt DA, Thomas E, Pope DP, de Winter AF, Macfarlane GJ, Bouter LM, et al. Occupational risk factors for shoulder pain: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57(7):433–42.

van der Windt DA, Zeegers MP, Kemper HC, Assendelft WJ, Scholten RJ. [Practice of systematic reviews. VI. Searching, selection and methodological evaluation of etiological research]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2000;144(25):1210–4.

Kunik ME, Cully JA, Snow AL, Souchek J, Sullivan G, Ashton CM. Treatable comorbid conditions and use of VA health care services among patients with dementia. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(1):70–5.

Leong IY, Nuo TH. Prevalence of pain in nursing home residents with different cognitive and communicative abilities. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(2):119–27.

Ahn H, Horgas A. The relationship between pain and disruptive behaviors in nursing home resident with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:14.

Volicer L, Van der Steen JT, Frijters DH. Modifiable factors related to abusive behaviors in nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(9):617–22.

Zieber CG, Hagen B, Armstrong-Esther C, Aho M. Pain and agitation in long-term care residents with dementia: use of the Pittsburgh Agitation Scale. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2005;11(2):71–8.

Black BS, Finucane T, Baker A, Loreck D, Blass D, Fogarty L, et al. Health problems and correlates of pain in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(4):283–90.

Brummel-Smith K, London MR, Drew N, Krulewitch H, Singer C, Hanson L. Outcomes of pain in frail older adults with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(11):1847–51.

Cipher DJ, Clifford PA, Roper KD. Behavioral manifestations of pain in the demented elderly. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7(6):355–65.

Norton MJ, Allen RS, Snow AL, Hardin JM, Burgio LD. Predictors of need-driven behaviors in nursing home residents with dementia and associated certified nursing assistant burden. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(3):303–9.

Williams CS, Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Reed PS. Characteristics associated with pain in long-term care residents with dementia. Gerontologist. 2005;45(1):68–73.

D’Astolfo CJ, Humphreys BK. A record review of reported musculoskeletal pain in an Ontario long term care facility. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6:5.

Gruber-Baldini AL, Zimmerman S, Boustani M, Watson LC, Williams CS, Reed PS. Characteristics associated with depression in long-term care residents with dementia. Gerontologist. 2005;45 Spec No 1(1):50–5.

Lin PC, Lin LC, Shyu YIL, Hua MS. Predictors of pain in nursing home residents with dementia: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(13–14):1849–57.

Morgan RO, Sail KR, Snow AL, Davila JA, Fouladi NN, Kunik ME. Modeling Causes of Aggressive Behavior in Patients With Dementia. Gerontologist. 2012;53(5):13–23.

Shega JW, Hougham GW, Stocking CB, Cox-Hayley D, Sachs GA. Factors associated with self- and caregiver report of pain among community-dwelling persons with dementia. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(3):567–75.

Shega JW, Ersek M, Herr K, Paice JA, Rockwood K, Weiner DK, et al. The multidimensional experience of noncancer pain: does cognitive status matter? Pain Med. 2010;11(11):1680–7.

Leonard R, Tinetti ME, Allore HG, Drickamer MA. Potentially modifiable resident characteristics that are associated with physical or verbal aggression among nursing home residents with dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(12):1295–300.

Volicer L, Frijters DH, Van der Steen JT. Relationship between symptoms of depression and agitation in nursing home residents with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;27(7):749–54.

Torvik K, Kaasa S, Kirkevold O, Rustoen T. Pain and quality of life among residents of Norwegian nursing homes. Pain Manag Nurs. 2010;11(1):35–44.

Volicer L, Krsiak M. Assessment and measurement of pain in patients with advanced dementia. [Czech]. Bolest. 2006;9(1):8–13.

Pieper MJ, van Dalen-Kok AH, Francke AL, Van der Steen JT, Scherder EJ, Husebo BS, et al. Interventions targeting pain or behaviour in dementia: A systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(4):1042–55.

Smalbrugge M, Jongenelis LK, Pot AM, Beekman AT, Eefsting JA. Pain among nursing home patients in the Netherlands: prevalence, course, clinical correlates, recognition and analgesic treatment–an observational cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7:3.

Landi F, Onder G, Cesari M, Russo A, Barillaro C, Bernabei R. Pain and its relation to depressive symptoms in frail older people living in the community: an observational study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29(3):255–62.

Lukas A, Mayer B, Fialova D, Topinkova E, Gindin J, Onder G, et al. Pain Characteristics and Pain Control in European Nursing Homes: Cross-sectional and Longitudinal Results From the Services and Health for Elderly in Long TERm care (SHELTER) Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(6):421–8.

Fisher SE, Burgio LD, Thorn BE, Allen-Burge R, Gerstle J, Roth DL, et al. Pain assessment and management in cognitively impaired nursing home residents: association of certified nursing assistant pain report, Minimum Data Set pain report, and analgesic medication use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(1):152–6.

Monroe TB, Gore JC, Chen LM, Mion LC, Cowan RL. Pain in people with Alzheimer disease: Potential applications for psychophysical and neurophysiological research. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;25(4):240–55.

Kunz M, Scharmann S, Hemmeter U, Schepelmann K, Lautenbacher S. The facial expression of pain in patients with dementia. Pain. 2007;133(1–3):221–8.

Husebo BS, Ballard C, Sandvik R, Nilsen OB, Aarsland D. Efficacy of treating pain to reduce behavioural disturbances in residents of nursing homes with dementia: cluster randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2011;343:d4065.

Chibnall JT, Tait RC, Harman B, Luebbert RA. Effect of acetaminophen on behavior, well-being, and psychotropic medication use in nursing home residents with moderate-to-severe dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(11):1921–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the COST program for COST action TD 1005.

The authors thank Mr. J.W. Schoones from the Walaeus Library of the Leiden University Medical Centre for his advice on the construction of the electronic search strategies.

Funding

This study was supported by the SBOH (employer of elderly care medicine/general practitioner trainees).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AvD performed the literature searches and selected eligible articles, extracted data from these articles, did the analyses and prepared the first draft of the review. MP contributed to the selection of articles, data extraction and methodological quality assessment of the systematic review. MdW and WA helped to determine the concept of the review and contributed to the writing. All authors reviewed and commented on the report. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0085-1.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

PRISMA 2009 checklist.

Additional file 2:

Quality assessment of longitudinal studies.

Additional file 3:

Rating scales for pain that were used in the reported studies.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

van Dalen-Kok, A.H., Pieper, M.J., de Waal, M.W. et al. Association between pain, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and physical function in dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 15, 49 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0048-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0048-6