Abstract

Background and Objective

Although paracetamol (acetaminophen) combined with other analgesics can reduce pain intensity in some pain conditions, its effectiveness in managing low back pain and osteoarthritis is unclear. This systematic review investigated whether paracetamol combination therapy is more effective and safer than monotherapy or placebo in low back pain and osteoarthritis.

Methods

Online database searches were conducted for randomised trials that evaluated paracetamol combined with another analgesic compared to a placebo or the non-paracetamol ingredient in the combination (monotherapy) in low back pain and osteoarthritis. The primary outcome was a change in pain. Secondary outcomes were (serious) adverse events, changes in disability and quality of life. Follow-up was immediate (≤ 2 weeks), short (> 2 weeks but ≤ 3 months), intermediate (> 3 months but < 12 months) or long term (≥ 12 months). A random-effects meta-analysis was conducted. Risk of bias was assessed using the original Cochrane tool, and quality of evidence using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE).

Results

Twenty-two studies were included. Pain was reduced with oral paracetamol plus a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) at immediate term in low back pain (paracetamol plus ibuprofen vs ibuprofen [mean difference (MD) − 6.2, 95% confidence interval (CI) −10.4 to −2.0, moderate evidence]) and in osteoarthritis (paracetamol plus aceclofenac vs aceclofenac [MD − 4.7, 95% CI − 8.3 to − 1.2, moderate certainty evidence] and paracetamol plus etodolac vs etodolac [MD − 15.1, 95% CI − 18.5 to − 11.8; moderate certainty evidence]). Paracetamol plus oral tramadol reduced pain compared with placebo at intermediate term for low back pain (MD − 11.7, 95% CI − 19.2 to − 4.3; very low certainty evidence) and osteoarthritis (MD − 6.8, 95% CI − 12.7 to −0.9; moderate certainty evidence). Disability scores improved in half the comparisons. Quality of life was infrequently measured. All paracetamol plus NSAID combinations did not increase the risk of adverse events compared to NSAID monotherapy.

Conclusions

Low-to-moderate quality evidence supports the oral use of some paracetamol plus NSAID combinations for short-term pain relief with no increased risk of harm for low back pain and osteoarthritis compared to its non-paracetamol monotherapy comparator.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Paracetamol plus a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug reduced pain in back pain (paracetamol plus ibuprofen vs ibuprofen) and osteoarthritis (paracetamol plus aceclofenac vs aceclofenac) at immediate term with a moderate quality of evidence. |

Paracetamol plus non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug combinations for both back pain and osteoarthritis did not increase the risk of serious adverse events or adverse events compared to its non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug monotherapy. |

1 Introduction

Musculoskeletal pain conditions such as low back pain and osteoarthritis are very common health conditions. Nearly 2 billion people live with musculoskeletal pain worldwide and low back pain and osteoarthritis are the predominant contributors to the overall burden of musculoskeletal conditions [1]. Low back pain is the leading cause of years lived with disability globally [2] and by 2050, more than 800 million people will have low back pain [2]. With an ageing and growing population, the prevalence of both low back pain and osteoarthritis has increased over the last two decades [1], with knee osteoarthritis accounting for 85% of the burden of osteoarthritis worldwide [1]. Pain is a key characteristic of musculoskeletal disorders and can significantly affect quality of life.

The management of musculoskeletal conditions often includes pharmacotherapy. Some clinical guidelines recommend paracetamol for musculoskeletal conditions [3]. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) can provide symptomatic relief to conditions such as tension headache [4], but for other conditions, such as osteoarthritis [5] and low back pain [6], paracetamol as a single ingredient has limited or no benefit, and subsequently is not recommended by several clinical guidelines [7,8,9,10]. However, paracetamol can be offered as a combination analgesic, for example paracetamol with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). The potential benefit of two drugs working together is to provide greater pain relief, possibly with a lower drug dose than the single ingredients alone and few side effects or a reduction in other harms. In contrast, certain drug combinations may potentiate harm or provide no additional benefit. This information is important to avoid the overuse of therapies that otherwise could be considered low-value care, i.e. where there is very little or no benefit or the risk of harm exceeds probable benefit [11].

The synergistic combination of paracetamol with other analgesics compared to placebo or monotherapy has been successfully demonstrated in many acute conditions, such as the use of paracetamol plus ibuprofen after oral surgery [12, 13] and post-surgical pain [14], with this combination being able to reduce morphine consumption following a hip replacement [15]. While the combination of paracetamol with aspirin and caffeine reduces episodic tension-type headaches compared with paracetamol alone [16], some observational studies suggest that paracetamol combination therapy might be effective in controlling musculoskeletal pain persistence [17]. However, the overall evidence for using paracetamol combinations in musculoskeletal conditions, such as low back pain and osteoarthritis, is unclear. Previous meta-analyses are outdated [18] or have been focussed on specific conditions and populations including acute post-operative pain [14, 19], dental pain [13, 20, 21] and paediatrics [22, 23]. One existing review investigating combination therapy in musculoskeletal injuries excluded low back pain [24] and was limited to only including paracetamol as a comparator [1]. Hence, an overview of the evidence on the benefits and harms of paracetamol combinations for prevalent and burdensome conditions such as low back pain and osteoarthritis is needed. Therefore, this review aimed to determine the current evidence on the effects of paracetamol combination drug therapy in reducing pain in patients with musculoskeletal conditions of low back pain or osteoarthritis compared to analgesic monotherapy or placebo. A secondary objective was to investigate safety outcomes and changes in disability and quality-of-life outcomes.

2 Methods

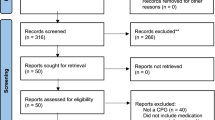

The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [25] and registered on PROSPERO (www.crd.york.ac.uk; CRD42023440808).

2.1 Data Sources and Searches

We searched the electronic databases of MEDLINE (OvidSP), Embase (OvidSP), PsycINFO (OvidSP), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (OvidSP), plus the trial registries of ClinicalTrials.gov and World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP, http://www.who.int/ictrp/en/) from their inception to 1st August, 2023 with no language or publication date restrictions. The search strategy is detailed in the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM). Manual searching and backward and forward citation tracking from the reference lists of the eligible studies were also conducted.

2.2 Study Selection

Eligible studies were randomised controlled trials that evaluated a paracetamol drug combination in a clinical setting compared to monotherapy or placebo for adult participants with low back pain or osteoarthritis. Combination drug therapy was defined as administering paracetamol combined with one or more different analgesic drugs together, compared with placebo or monotherapy. For the monotherapy comparator, we included studies where the control was either paracetamol or another analgesic that formed part of the paracetamol combination (e.g. paracetamol and NSAID vs NSAID alone). There was no restriction on the type of clinical settings included. Participants with low back pain could include referred leg pain symptoms. We excluded trials enrolling participants with low back pain attributed to pathological (e.g. cancer, infection) and non-mechanical causes of low back pain (e.g. post-surgery), dental pain and headache/migraine or those who were pregnant.

Two review authors from a panel (ZC, KH, HL, SI, SM) independently screened identified titles and abstracts to determine eligibility. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by arbitration by a third independent reviewer (SM or CAS). The authors sought colleagues to assist with reading articles written in languages that could not be read by the authors.

2.3 Data Extraction

Two reviewers from a panel (ZC, KH, HL, SI, SM) independently extracted data on standardised and piloted forms. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by arbitration by a third independent reviewer (SM or CAS). Extracted data included bibliometric information (authors, title, year of publication, language, funding, conflict of interest), study characteristics (sample size, randomisation method, concealment, blinding, setting), participant information (age, sex, diagnosis, symptom duration, rescue medicine use), intervention and control (drug dose, duration, mode of delivery), outcome data (pre/post pain intensity, disability, quality of life, serious adverse events [SAEs], adverse events [AEs], withdrawals because of AEs, study withdrawals) and data completeness (percentage of missing data, how missing data were handled). Serious AEs were defined as events that were life threatening or resulted in death, hospitalisation, significant incapacity, congenital anomaly or birth defects, or as defined by the included study. Non-SAEs were considered as non-serious or side effects, for example nausea and headache. Medicines were categorised according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system [26]. Post-treatment scores were preferentially used, and mean changes from baseline scores were used if the former was unavailable. If standard deviations (SDs) were not reported, we attempted to estimate them from the confidence intervals (CIs) or other measures of variance. If this was not possible, we used the SD for that outcome relevant for that intervention or control group at baseline. No study authors were contacted to clarify any uncertainties or obtain additional information.

Follow-up timepoints included immediate (≤ 2 weeks), short (> 2 weeks but ≤ 3 months), intermediate (> 3 months but < 12 months) or long (≥ 12 months) terms. If multiple observations were reported for each timepoint, one observation was chosen closest to 2 weeks, 7 weeks, 6 months and 12 months for each follow-up period.

2.4 Risk of Bias Assessment

Two reviewers from a panel (ZC, KH, HL, SI, SM) independently assessed the risk of bias using the original Cochrane Risk of Bias tool [27]. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by arbitration by a third independent reviewer (SM or CAS). The criteria are detailed in the ESM.

2.5 Data Synthesis

The study flow was summarised into a study flow diagram using the PRISMA statement [25]. Outcome data were organised by intervention per Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical drug group (NSAIDs, opioid analgesics, sorted by alphabetical order), then comparator (monotherapy, then placebo) per population (low back pain, osteoarthritis) followed by timepoints. Continuous data were presented as means and SDs and dichotomous data as proportions (n/N). Continuous outcomes were converted to a 0–100 scale if needed to aid comparison.

A meta-analysis was conducted using a random-effects model in Review Manger 5.3 and the results presented via forest plots. Continuous outcomes are reported as the mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs, and dichotomous outcomes are reported using risk difference with 95% CIs to accommodate zero events. The overall quality of evidence was assessed using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [28] and is detailed in the ESM.

3 Results

The search retrieved 13,186 records, of which 22 studies were included (Fig. 1). A list of studies excluded at full text are presented in the ESM. Studies were published between 1976 and 2021. All studies were published in English. Sixteen studies had some form of industry sponsorship. Sample sizes ranged from 50 to 511 participants. Study characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

3.1 Participants

Most studies focussed on participants with low back pain (16 studies [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]), followed by osteoarthritis (five studies [45,46,47,48,49]), and one study enrolled both populations [50]. Nine studies focussed on participants with acute symptoms [29,30,31, 38, 43, 44, 46,47,48], including three with acute symptoms on chronic presentation (osteoarthritis “flare up”) [46,47,48], one study of subacute symptoms (10–42 days) [40] and the remaining studies with chronic symptoms [32,33,34,35,36,37, 39, 41, 42, 45, 49, 50]. Of the low back pain studies, only one study included participants with intervertebral disc disease/nerve root entrapment [33]; other studies actively excluded participants with symptoms or neurologic deficits in the lower extremities [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44, 50], or did not state they were included [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42, 44, 50].

The mean age of participants was 52.8 years (SD 11.0; 15 studies, range 37.0–60.1 years). Studies involving participants with low back pain were, on average, younger (49.3 years, SD 11.4; 12 studies) than studies with participants with osteoarthritis (63.8 years, SD 7.4; 3 studies). Participant characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

3.2 Risk of Bias

Forty percent of risk of bias scores were marked as unclear because of insufficient available information. This was driven by the lack of detail on random sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding in studies found through clinical trial registries when no peer review publication was associated with the trial [33,34,35,36,37, 50]. These studies also scored poorly in the remaining domains. Eight studies scored a low risk of bias in at least half the domains [29, 30, 32, 39, 41, 42, 44, 49] (Fig. 2).

3.3 Interventions

All but one trial [43] delivered combination therapy orally (e.g. via tablets or capsules). Paracetamol plus tramadol was the most frequent combination assessed (ten trials [31, 32, 39,40,41,42, 45, 48,49,50]), with only one study investigating an extended-release version of the combination [32]. These trials included both low back pain and osteoarthritis populations.

Studies assessing paracetamol plus another opioid analgesic included hydrocodone [34,35,36,37], or oxycodone [33], all compared to placebo, and in chronic low back pain. Paracetamol combinations with an NSAID included aceclofenac [47], etodolac [29, 46] or ibuprofen [30, 38], with only one of these studies compared to a placebo [30]. Other paracetamol combinations included a muscle relaxant of orphenadrine [43], and one study combining paracetamol with a chlorpheniramine, aspirin and caffeine preparation [44]. Monotherapy comparators were noted to only be assessed in studies with participants having acute presentations [29, 38, 40, 43, 44, 46, 47]. Paracetamol combinations are summarised in Table 2.

3.4 Outcomes

3.4.1 Pain

All studies reported pain outcomes, 18 studies used the visual analogue scale or numerical pain rating scale, three studies use categorical measures [30, 43, 49] and one study used summed pain scores [31]. There were no long-term data.

Paracetamol plus NSAID combination therapy reduced pain intensity in low back pain in one combination, paracetamol plus ibuprofen versus ibuprofen at immediate term (MD −6.2, 95% CI −10.4 to −2.0; one study; moderate evidence), and in two combinations in osteoarthritis, paracetamol plus aceclofenac versus aceclofenac (MD −4.7, 95% CI −8.3 to −1.2; immediate term, one study; moderate evidence) and paracetamol plus etodolac versus etodolac (MD −15.1, 95% CI −18.5 to −11.8; immediate term, one study; moderate evidence) [Fig. 3]. However, paracetamol plus etodolac versus etodolac at immediate term did not reduce pain in low back pain (Fig. 3). Paracetamol plus tramadol reduced pain compared with placebo at intermediate term for low back pain (MD −11.7, 95% CI −19.2 to −4.3; two studies, very low evidence) and osteoarthritis (MD −6.8, 95% CI −12.7 to −0.9; one study, moderate evidence) [Fig. 3].

Eleven studies were unable to be included in the meta-analyses as they did not provide measures of variability for means and could not be calculated [31, 32, 48], recorded categorical outcomes [30, 43, 49], did not report group data [34] or they were industry trials in which pain scores were adjusted values from statistical models in clinical trial registration pages [33, 35,36,37]. Of these 11 studies, seven trials concluded the combination was more effective than the comparator in reducing pain [31, 32, 34,35,36, 48, 49].

3.4.2 Disability

Sixteen studies measured disability outcomes. Validated measures used included the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire [29, 30, 34, 39, 41, 42, 44], Korean Oswesty Disability Index [32], Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale [38] or Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) [35, 45,46,47,48,49]. There were no intermediate-term or long-term data.

Paracetamol plus NSAID combination therapy improved disability scores in low back pain in one combination, paracetamol plus ibuprofen versus ibuprofen, immediate term (MD −9.2, 95% CI −16.8 to −1.6; one study; moderate evidence). The paracetamol plus NSAID combination therapy improved disability scores in osteoarthritis in one combination, paracetamol plus etodolac versus etodolac, immediate term (MD −8.9, 95% CI −12.1 to −5.7; one study; moderate evidence) [ESM].

Paracetamol plus tramadol improved disability scores in low back pain when compared with placebo at short term (tramadol extended-release vs placebo MD −4.0, 95% CI −7.9 to −0.1, one study, low evidence) and in osteoarthritis at immediate term (MD −4.7, 95% CI −8.8 to −0.6, one study, moderate evidence) and intermediate term (MD −4.0, 95% CI −8.0 to −0.03, one study, moderate evidence) [ESM].

Eleven studies were not included in the meta-analyses as they did not report disability outcomes [31, 33, 36, 37, 40, 50] or data [34, 35], reported descriptively as participant’s self-reported disability in days [43], or did not provide measures of variability for means and could not be calculated [44, 48]. Of the latter, one study reported an improvement in disability in the combination group compared with placebo [48].

3.4.3 Quality of Life

Three studies reported quality-of-life outcomes, all using SF-36 questionnaire that reported long-term data [39, 41, 45]. Paracetamol plus tramadol did not improve quality of life compared with placebo in low back pain or osteoarthritis populations (ESM).

3.4.4 Harms

Fifteen studies reported SAEs (ESM). Serious AEs were infrequent. No combination therapy increased the risk of SAEs compared to individual controls (ESM). Seven studies did not report SAEs [29, 30, 38, 42, 44, 47, 49].

Nineteen studies reported AEs (Fig. 4). Paracetamol plus an NSAID did not increase the risk of AEs in low back pain or osteoarthritis compared to their NSAID monotherapy or placebo (Fig. 4; comparison 1.6.1–1.6.5). Five out of the nine comparisons of paracetamol plus an opioid analgesic (tramadol or oxycodone) compared with placebo increased the risk of adverse events in low back pain and osteoarthritis (Fig. 4; comparison 1.6.7, 1.6.8, 1.6.10, 1.6.11, 1.6.14). In contrast, there was a lower risk of AEs with the addition of paracetamol to tramadol than tramadol alone in low back pain (risk difference −0.22, 95% CI −0.4 to −0.06 at immediate term, one study, moderate evidence) [Fig. 4; comparison 1.6.6]. However, in this study, adding paracetamol may not be protective as a higher dose of tramadol was used in the control arm (50 mg; maximum 24-hour dose of tramadol 400 mg) compared with the combination tablet (paracetamol 325 mg + tramadol 37.5 mg; maximum 24-hour dose: paracetamol 2600 mg and tramadol 300 mg) [Table 2]. Study withdrawals because of AEs and for any reason were not significant in most comparisons (10 out of 14 comparisons; 10 out of 16 comparisons respectively; ESM).

4 Discussion and Conclusions

Paracetamol, in combination with oral NSAIDs of aceclofenac and etodolac, was found to reduce pain at immediate term more than its NSAID monotherapy with no increased risk of AEs in participants with osteoarthritis. While paracetamol plus etodolac at immediate term did not reduce pain compared to its NSAID monotherapy in participants with low back pain, paracetamol plus ibuprofen at immediate term did reduce pain and disability compared with ibuprofen alone without an increased risk of AEs in low back pain. However, these results are from single trials with a low-to-moderate quality of evidence. Paracetamol plus the oral opioid analgesic of tramadol reduced pain at immediate term in osteoarthritis but with increased AEs both with a moderate quality of evidence, and there was only a very low quality of evidence for this combination in providing pain relief in low back pain at immediate term. No comparison increased the risk of SAEs and no long-term data were available for any outcome.

The use of analgesics, including paracetamol, in managing low back pain and osteoarthritis is common [51,52,53] despite trials finding paracetamol being efficacious for hip and knee osteoarthritis but not for low back pain [4, 54]. The addition of another analgesic agent has the potential to provide additional pain relief compared with the single ingredient when used alone. These benefits have been identified in previous reviews in other pain conditions, for example, acute pain [55], or when paracetamol is used with other agents, such as caffeine compared to placebo in acute migraine attacks [53]. However, in these reviews, AEs are more common in the combination therapy groups [55, 56]. In contrast, paracetamol with another oral analgesic, such as an NSAID, has been found to not reduce pain more than paracetamol monotherapy in acute musculoskeletal injuries (i.e. strains, sprains or contusions, in the absence of a fracture) [24, 57]. Other reviews have been unable to make firm conclusions because of the quality of the evidence being too low [58], insufficient data [59] and the lack of relevant trials [18, 58]. The lack of trials is common to several reviews [19, 21, 24, 57, 58].

The introduction of paracetamol combination tablets to the commercial market has expanded potential options in the clinical management of pain. Simple analgesics such as paracetamol are easily accessible to consumers in many countries, often available without prescription as the ingredients are considered safe because of their long-term established safety profiles. As paracetamol lacks significant anti‐inflammatory activity, adding an NSAID can provide additional pharmacodynamic benefits in the absence of contra-indications. For example, avoiding NSAID use in the presence of peptic ulcers and cardiovascular disease [60, 61]. Although many trials used less than the recommended daily dose of paracetamol (4 g/day), this review found three paracetamol plus NSAID combinations (aceclofenac, etodolac, ibuprofen) provided greater analgesic benefits with no increase in SAEs or AEs compared to their NSAID controls [38, 46, 47]. One of these three combinations was paracetamol plus ibuprofen in participants with low back pain [38], a combination tablet available without prescription in several countries including Australia, USA, UK and NZ since 2010. They are indicated for temporary relief in arthritis and backache [62, 63]. However, this review found no trials testing this combination in osteoarthritis and only one industry-sponsored trial testing in participants with acute low back pain [38]. Robust future trials may further examine the paracetamol plus ibuprofen combination as a potential safe analgesic agent for reducing pain and improving physical function in clinical low back pain and osteoarthritis and for long-term use. One paracetamol combination trial that was excluded from this review because participants had self-reported knee pain of any origin that showed that paracetamol plus ibuprofen reduced knee pain more than the same dose of the single ingredients with a comparable frequency of AEs between groups [64].

Most clinical guidelines make pharmacotherapy recommendations based on single-ingredient medicines. Regarding clinical guidelines for the management of low back pain and osteoarthritis, most guidelines do not recommend opioid analgesics, reflecting the evidence indicating their benefits often do not outweigh their increased risk of harm [65]. However, the use of paracetamol plus a weak opioid is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence for the management of low back pain but with clear guidance; only if an NSAID is contraindicated, not tolerated or has been ineffective [8]. The routine use of weak opioids and paracetamol individually is not recommended [8]. In circumstances where clinicians are considering prescribing this combination or paracetamol with other opioids, this review provides a summary of the current evidence whereby clinicians can consider both positive and negative findings and what trials have been conducted. Furthermore, the review results do not categorise opioid analgesics based on strength, accommodating the differences in drug classifications among countries. For example, tramadol, which is not consistently classed as a weak or strong opioid internationally, may contribute to people receiving different clinical management for the same condition across countries, while the opioid codeine, generally considered as a “weak” opioid, is available in combination with paracetamol and widely available internationally. However, the effectiveness and safety of this combination have not been investigated for use in osteoarthritis or low back pain populations. The lack of this evidence for the latter has previously been identified [18].

This review provides a thorough and contemporary evaluation of the paracetamol combination therapy necessary to understand these drugs in the current management of low back pain and osteoarthritis. The search scope was not limited in date, publication source or language. This review highlights important limitations in available data. There is a paucity of trials in the field, a lack of exploration of dosage regimes and a lack of long-term data that could be important to inform clinical management, such as the long-term management of chronic osteoarthritis symptoms when combination therapy is used to manage symptom flare-ups. In response to the limited number of trials per combination, the overall assessment of the quality of evidence using the GRADE approach was adjusted accordingly. Furthermore, potential bias from funding and conflicts of interest was included when assessing the risk of bias. Including industry-funded trials is an important part of the evidence landscape and drug development for the availability of future medicines.

The ever-evolving evidence of the benefits and harms of pharmacological therapy allows for the opportunity to improve future research. Simple methodological improvements are warranted around increased reporting transparency in industry trials, as uncovered in the risk of bias assessment and understanding medium-term and long-term benefits and harms. More robust evidence could confirm the effectiveness of certain paracetamol combinations, such as paracetamol plus ibuprofen, replicated independently from industry sponsorship, and using larger sample sizes for adequate power to determine their benefits. Evidence from future trials will have the capacity to provide confidence in the effect of paracetamol combinations that currently only have evidence from single studies despite clinician support, such as the paracetamol plus etodolac combination [66]. A randomised trial using a factorial design would methodologically determine the effect of the combination therapy against each monotherapy and placebo, potentially investigating if lower doses are equally effective, and closing a current evidence gap.

References

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators, James SL, Abate D, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858.

Ferreira ML, de Luca K, Haile LM, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990–2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023;5(6):e316–29.

Qaseem A, McLean RM, O’Gurek D, Batur P, Lin K, Kansagara DL, et al. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic management of acute pain from non-low back, musculoskeletal injuries in adults: a clinical guideline from the American College of Physicians and American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(9):739–48.

Abdel Shaheed C, Ferreira G, Dmitritchenko A, McLachlan AJ, Day RO, Saragiotto B, et al. The efficacy and safety of paracetamol for pain relief: an overview of systematic reviews. Med J Aust. 2021;214(7):324–31.

Leopoldino AO, Machado GC, Ferreira PH, et al. Paracetamol versus placebo for knee and hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2(2):CD013273.

Williams CM, Maher CG, Latimer J, et al. Efficacy of paracetamol for acute low-back pain: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9954):1586–96.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC). Low back pain clinical care standard. 2022. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/clinical-care-standards/low-back-pain-clinical-care-standard/implementation-resources. Accessed 19 Jun 2024.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management [NG59]. 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59. Accessed 19 Jun 2024.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Osteoarthritis in over 16s: diagnosis and management [NG226]. 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng226. Accessed 19 Jun 2024.

Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27(11):1578–89.

Elshaug AG, Rosenthal MB, Lavis JN, et al. Levers for addressing medical underuse and overuse: achieving high-value health care. Lancet. 2017;390(10090):191–202.

Daniels SE, Goulder MA, Aspley S, Reader S. A randomised, five-parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial comparing the efficacy and tolerability of analgesic combinations including a novel single-tablet combination of ibuprofen/paracetamol for postoperative dental pain. Pain. 2011;152(3):632–42.

Mehlisch DR, Aspley S, Daniels SE, Southerden KA, Christensen KS. A single-tablet fixed-dose combination of racemic ibuprofen/paracetamol in the management of moderate to severe postoperative dental pain in adult and adolescent patients: a multicenter, two-stage, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, factorial study. Clin Ther. 2010;32(6):1033–49.

Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA. Single dose oral ibuprofen plus paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(6):CD010210.

Thybo KH, Hägi-Pedersen D, Dahl JB, et al. Effect of combination of paracetamol (acetaminophen) and ibuprofen vs either alone on patient-controlled morphine consumption in the first 24 hours after total hip arthroplasty: the PANSAID randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(6):562–71.

Diener HC, Gold M, Hagen M. Use of a fixed combination of acetylsalicylic acid, acetaminophen and caffeine compared with acetaminophen alone in episodic tension-type headache: Meta-analysis of four randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover studies. J Headache Pain. 2014;15(1):76.

Bettiol A, Marconi E, Vannacci A, et al. Effectiveness of ibuprofen plus paracetamol combination on persistence of acute musculoskeletal disorders in primary care patients. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021;43(4):1045–54.

Mathieson SKR, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, McLachlan AJ, Koes BW, Lin CC. Combination drug therapy for the management of low back pain and sciatica; systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2019;20(1):1–15.

Abushanab D, Al-Badriyeh D. Efficacy and safety of ibuprofen plus paracetamol in a fixed-dose combination for acute postoperative pain in adults: meta-analysis and a trial sequential analysis. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(1):105–20.

Miroshnychenko A, Ibrahim S, Azab M, et al. Acute postoperative pain due to dental extraction in the adult population: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Dent Res. 2023;102(4):391–401.

Bailey E, Worthington HV, van Wijk A, Yates JM, Coulthard P, Afzal Z. Ibuprofen and/or paracetamol (acetaminophen) for pain relief after surgical removal of lower wisdom teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12:CD004624.

Sjoukes A, Venekamp RP, van de Pol AC, et al. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, alone or combined, for pain relief in acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12(12):CD011534.

Perrott DA, Piira T, Goodenough B, Champion GD. Efficacy and safety of acetaminophen vs ibuprofen for treating children’s pain or fever: a meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(6):521–6.

Scott G, Gong J, Kirkpatrick C, Jones P. Systematic review and meta-analysis of oral paracetamol versus combination oral analgesics for acute musculoskeletal injuries. Emerg Med Australas. 2021;33(1):107–13.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, The PRISMA, et al. statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2020;2021(372): n71.

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment, 2023. Oslo 2022. https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index_and_guidelines/guidelines/. Accessed 19 Jun 2024.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343: d5928.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE Guidelines: 1. Introduction GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clinl Epidemiol. 2011;64:383–94.

Bayram S, Sahin K, Anarat FB, et al. The effect of oral magnesium supplementation on acute non-specific low back pain: prospective randomized clinical trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;47:125–30.

Friedman BW, Irizarry E, Chertoff A, et al. Ibuprofen plus acetaminophen versus ibuprofen alone for acute low back pain: an emergency department-based randomized study. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(3):229–35.

Lasko B, Levitt RJ, Rainsford KD, Bouchard S, Rozova A, Robertson S. Extended-release tramadol/paracetamol in moderate-to-severe pain: a randomized, placebo-controlled study in patients with acute low back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(5):847–57.

Lee JH, Lee CS, Ultracet ER Study Group. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the extended-release tramadol hydrochloride/acetaminophen fixed-dose combination tablet for the treatment of chronic low back pain. Clin Ther. 2013;35(11):1830–40.

NCT00315445. The safety and efficacy of the Buprenorphine Transdermal System (BTDS) in subjects with chronic back pain (BP96-0604). Last updated 2012. https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00315445. Accessed 19 Jun 2024.

NCT00325949. A study of pain relief in low back pain. Last updated 2011. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00325949?tab=history. Accessed 19 Jun 2024.

NCT00761150. Study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of ABT-712 in subjects with moderate to severe chronic low back pain (CLBP). Last updated 2014. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00761150. Accessed 19 Jun 2024.

NCT00763321. Study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of ABT-712 in subjects with moderate to severe chronic low back pain (CLBP). Last updated 2014. https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00763321?term=NCT00763321&rank=1. Accessed 19 Jun 2024.

NCT01364922. Phase 2 chronic low back pain study. Last updated 2014. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01364922. Accessed 19 Jun 2024.

Ostojic P, Radunovic G, Lazovic M, Tomanovic-Vujadinovic S. Ibuprofen plus paracetamol versus ibuprofen in acute low back pain: a randomized open label multicenter clinical study. Acta Reumatol Port. 2017;42(1):18–25.

Peloso PM, Fortin L, Beaulieu A, Kamin M, Rosenthal N. Analgesic efficacy and safety of tramadol/ acetaminophen combination tablets (Ultracet) in treatment of chronic low back pain: a multicenter, outpatient, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(12):2454–63.

Perrot S, Krause D, Crozes P, Naïm C. Efficacy and tolerability of paracetamol/tramadol (325 mg/37.5 mg) combination treatment compared with tramadol (50 mg) monotherapy in patients with subacute low back pain: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, 10-day treatment study. Clin Ther. 2006;28(10):1592–606.

Ruoff GE, Rosenthal N, Jordan D, Karim R, Kamin M. Tramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets for the treatment of chronic lower back pain: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled outpatient study. Clin Ther. 2003;25(4):1123–41.

Schiphorst Preuper HR, Geertzen JH, van Wijhe M, et al. Do analgesics improve functioning in patients with chronic low back pain? An explorative triple-blinded RCT. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(4):800–6.

Tervo T, Petaja L, Lepisto P. A controlled clinical trial of a muscle relaxant analgesic combination in the treatment of acute lumbago. Br J Clin Pract. 1976;30(3):62–4.

Voicu VA, Mircioiu C, Plesa C, et al. Effect of a new synergistic combination of low doses of acetylsalicylic acid, caffeine, acetaminophen, and chlorpheniramine in acute low back pain. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:607.

Emkey R, Rosenthal N, Wu SC, Jordan D, Kamin M. Efficacy and safety of tramadol/acetaminophen tablets (Ultracet) as add-on therapy for osteoarthritis pain in subjects receiving a COX-2 nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(1):150–6.

Pareek A, Chandurkar N, Ambade R, Chandanwale A, Bartakke G. Efficacy and safety of etodolac-paracetamol fixed dose combination in patients with knee osteoarthritis flare-up: a randomized, double-blind comparative evaluation. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(7):561–6.

Pareek A, Chandurkar N, Sharma VD, Desai M, Kini S, Bartakke G. A randomized, multicentric, comparative evaluation of aceclofenac-paracetamol combination with aceclofenac alone in Indian patients with osteoarthritis flare-up. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10(5):727–35.

Rosenthal NR, Silverfield JC, Wu SC, Jordan D, Kamin M, Group C-S. Tramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets for the treatment of pain associated with osteoarthritis flare in an elderly patient population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(3):374–80.

Silverfield JC, Kamin M, Wu SC, Rosenthal N. Tramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets for the treatment of osteoarthritis flare pain: a multicenter, outpatient, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, add-on study. Clin Ther. 2002;24(2):282–97.

NCT00736853. An efficacy and safety study of acetaminophen plus tramadol hydrochloride (JNS013) in participants with chronic pain. Last updated 2013. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00736853. Accesesd 19 Jun 2024.

Pickering G, Mezouar L, Kechemir H, Ebel-Bitoun C. Paracetamol use in patients with osteoarthritis and lower back pain: infodemiology study and observational analysis of electronic medical record data. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022;8(10): e37790.

Yang Z, Mathieson S, Kobayashi S, et al. Prevalence of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs prescribed osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2023;75(11):2345–58.

Wertheimer G, Mathieson S, Maher CG, et al. The prevalence of opioid analgesic use in people with chronic noncancer pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Pain Med. 2021;22(2):506–17.

Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, et al. Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. BMJ. 2015;350: h1225.

Alexander L, Hall E, Eriksson L, Rohlin M. The combination of non-selective NSAID 400 mg and paracetamol 1000 mg is more effective than each drug alone for treatment of acute pain: a systematic review. Swed Dent J. 2014;38(1):1–14.

Diener HC, Gaul C, Lehmacher W, Weiser T. Aspirin, paracetamol (acetaminophen) and caffeine for the treatment of acute migraine attacks: a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29(1):350–7.

Ridderikhof ML, Saanen J, Goddijn H, et al. Paracetamol versus other analgesia in adult patients with minor musculoskeletal injuries: a systematic review. Emerg Med J. 2019;36(8):493–500.

de Sevaux JLH, Damoiseaux RA, van de Pol AC, et al. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, alone or combined, for pain relief in acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;8(8):CD011534.

Straube C, Derry S, Jackson KC, et al. Codeine, alone and with paracetamol (acetaminophen), for cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(9):CD006601.

Australian medicines handbook online. Adelaide (SA): Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd; March 2024. https://www.amhonlineamh.net.au/. Accessed 19 Jun 2024.

Geczy QE, Thirumaran AJ, Carroll PR, McLachlan AJ, Hunter DJ. What is the most effective and safest non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug for treating osteoarthritis in patients with comorbidities? Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2023;19(10):681–95.

Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Australian Product Information: Nuromol dual action pain relief (ibuprofen 200mg and paracetamol 500mg) liquid capsule. TGA. 2020. https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/pdf?OpenAgent=&id=CP-2022-PI-01899-1&d=20240322172310101. Accessed 19 Jun 2024.

Medsafe. Mersynofen® ibuprofen and paracetamol consumer medicine information (CMI). New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority. 2023. https://www.medsafe.govt.nz/consumers/cmi/m/mersynofen.pdf. Accessed 19 Jun 2024.

Doherty M, Hawkey C, Goulder M, et al. A randomised controlled trial of ibuprofen, paracetamol or a combination tablet of ibuprofen/paracetamol in community-derived people with knee pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(9):1534–41.

Murnion B. Combination analgesics in adults. Aust Prescr. 2010;33(4):113–5.

Farinelli L, Riccio M, Gigante A, De Francesco F. Pain management strategies in osteoarthritis. Biomedicines. 2024;12(4):805.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Conflict of Interest

Zhiying Cao, Kaiyue Han, Hanting Lu, Sandalika Illangamudalige, Christina Abdel Shaheed, Lingxiao Chen, Asad E Patanwala, Christopher G Maher, Chung-Wei Christine Lin, Lyn March and Stephanie Mathieson have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article. Andrew J. McLachlan has provided education services sponsored by Bayer and Haleon. The Sydney Pharmacy School receives research funding from GSK for a scholarship supervised by Andrew J. McLachlan. Manuela L. Ferreira and Andrew J. McLachlan serve on an advisory board for Viatris related to celecoxib use in primary care.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

SM conceived the review and conducted the search. ZC, KH, HL, SI and SM extracted data. SM and ZC conducted the analyses. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. SM drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, Z., Han, K., Lu, H. et al. Paracetamol Combination Therapy for Back Pain and Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Drugs (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-024-02065-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-024-02065-w