Abstract

Background

In a period of change in the organization of primary care, Interprofessional Collaboration (IPC) is presented as one of the solutions to health issues. Although the number of inter-professional interventions grounded in primary care increases in all developed countries, evidence on the effects of these collaborations on patient-centred outcomes is patchy. The objective of our study was to assess the effects of IPC grounded in the primary care setting on patient-centred outcomes.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature review using the PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO and CINAHL databases from 01/01/1995 to 01/03/2021, according to the PRISMA guidelines. Studies reporting the effects of IPC in primary care on patient health outcomes were included. The quality of the studies was assessed using the revised Downs and Black checklist.

Results

Sixty-five articles concerning 61 interventions were analysed. A total of 43 studies were prospective and randomized. Studies were classified into 3 main categories as follows: 1) studies with patients at cardiovascular risk (28 studies)—including diabetes (18 studies) and arterial hypertension (5 studies); 2) studies including elderly and/or polypathological patients (18 studies); and 3) patients with symptoms of mental or physical disorders (15 studies). The number of included patients varied greatly (from 50 to 312,377). The proportion of studies that reported a positive effect of IPC on patient-centred outcomes was as follows: 23 out of the 28 studies including patients at cardiovascular risk, 8 out of the 18 studies of elderly or polypathological patients, and 11 out of the 12 studies of patients with mental or physical disorders.

Conclusions

Evidence suggests that IPC is effective in the management of patients at cardiovascular risk. In elderly or polypathological patients and in patients with mental or physical disorders, the number of studies remains very limited, and the results are heterogeneous. Researchers should be encouraged to perform studies based on comparative designs: it would increase evidence on the positive effect and benefits of IPC on patient variables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of primary care, defined as a model of care that supports first-contact, accessible, continuous, comprehensive and coordinated person-focused care, is a global priority [1]. Studies have already shown that most patients are treated in a primary care setting [2, 3]. Most patients suffering from common diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma only consult a primary care provider [4]. The ageing of populations, the growing importance of chronic pathologies, the international shortage in the health care workforce [5], and the growing complexity of care pathways call for development of new modalities of practice in primary care.

Functioning in a primary care team, based on Interprofessional Collaboration (IPC), is widely supported by the health authorities in France [6], similar to existing models in several countries [7]. IPC is defined as several health workers from different professional backgrounds providing comprehensive services by working with patients, their families, and other caregivers [8]. This definition can be supplemented by the need for contact, negotiation and interaction among health care professionals. As this concept is recent and vast, several terms have been used, but the term IPC is the most currently used [9]. Part of these IPC teams regroup professionals in the same practice. Many practices work as a team of GP's, nurses (including Advanced Nurse Practitioners), paramedics (including Advanced Clinical Practitioners), clinical pharmacists, physiotherapists, physician associates and others. In this model, an integrated and collaborative approach to patient care has been developed. The literature on this subject shows a recent emulation with numerous articles in many journals [1, 7,8,9,10,11]. Several authors have reported that working as a team is a source of satisfaction among professionals [7, 10]. A 2018 literature review reported how primary care teams were formed [11], but it did not report any information on the effect of these organizations on patient-centred outcomes.

Some authors have focused on the team-based approach for specific pathologies for which collaborations largely mobilize specialists and hospital professionals, but these investigations concern secondary rather than primary care services [12,13,14]. While a recent literature review [15] investigated the effect of IPC in a primary care setting on adults with diabetes and/or hypertension, we wanted to further investigate which areas of treatment and primary care team organization had an effect on patient-centred outcomes.

A better understanding and better characterization the composition of IPC teams and the health fields in which this collaboration would be relevant and effective for patients is important for decision-makers and professionals who wish to engage in the evolution of their practice. Which professionals are involved in IPC? For which treatments and illnesses have results been obtained? For which treatments and diseases have we not obtained convincing results?

The objective of this study was to assess the effects of IPC grounded in primary care setting on patients-centred outcomes.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines [16]. We searched for studies published between January 1st, 1995 and March 1st, 2021. To ensure that we found all research articles published by the various health professionals, we chose to increase the number of search engines normally used. The following databases were searched: PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO and CINAHL. Additional articles that were found by hand searching the references were also reviewed. The following research algorithms were used 1) PubMed: ("Intersectoral Collaboration"[Mesh] OR "Cooperative Behavior"[Mesh] OR "Patient Care Team"[Mesh:NoExp]) AND ("Primary Health Care"[Mesh]) AND ("Outcome and Process Assessment, Health Care"[Mesh]); and 2) Embase, PsycINFO and CINAHL: « intersectoral collaboration», « cooperative behaviour», « patient care team» AND « primary health care» AND « outcome and process assessment, health care». First, the titles were reviewed, and then the abstracts and full texts of the selected articles were reviewed independently by two reviewers with the Abstrackr tool [17]. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus; MJ, MA, and JFH resolved any remaining disagreements.

After reading the full texts, we included the following studies in this analysis:

-

studies reporting on IPC

-

studies conducted in the primary care setting, involving primary care providers exclusively

-

studies involving at least 2 different primary care providers, regardless of the type and level of collaboration (from a simple phone call to a multidisciplinary medical appointment).

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

interventions involving multidisciplinary teams working between primary and secondary care

-

the absence of a primary endpoint centred on patient health (studies focusing on economic outcomes, manuscripts reporting practices for declarative data only)

-

the absence of a comparative design with a control group and statistical analysis (studies based on a before-after design involving the follow-up of only one cohort of patients were excluded)

-

abstracts not respecting the IMRAD structure

-

manuscripts not accessible in English.

One reviewer (MA) independently extracted data using a prepiloted form and was supervised by a second reviewer (CB), and the following data were collected: study country, pathology(ies) studied, intervention, the number of patients included, design, study duration, main outcome measures, and patient outcomes (selected on the basis of frequency of reporting and clinical relevance). For consistency and clarify of presentation, the results centred on patient outcomes are grouped within 3 categories in the remainder of the manuscript: 1- patients at cardiovascular risk, 2-polypathological and elderly patients, and 3- patients with mental health problems, chronic pain and unexplained complaints.

The quality of the studies was then assessed using the revised Downs and Black Checklist [18]. The checklist includes 27 items on reporting (10 items), external validity (3 items), internal validity (13 items), and power (1 item). Similar to others studies, the power item was modified regarding whether a power analysis was described (0 = not reported, 1 = reported). The maximum possible score is 28 for randomized studies and 25 for nonrandomized studies. Quality was categorized by using the following Downs and Black score ranges: strong (21-28), moderate (14-20), limited (7-13), and poor (≤ 7) [19].

Results

Selection and general description of the studies

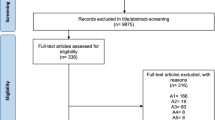

In total, 3494 titles, 1280 abstracts and 342 full-text papers were screened for eligibility using the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Sixty-five papers were included in the review, comprising 61 interventions [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84].

A large majority of the included studies were from North America (40) or Europe (13). The other studies were from Asia (5), Australia (2), and South America (1). Forty-three studies were prospective and randomized. Four studies were carried out over a period of more than 24 months [32, 34, 36, 64].

Depending on the studies, the number of patients included varied between 50 and 312,377: 5 studies included more than 5,000 patients, 37 studies included between 200 and 5,000 patients, and 19 studies included fewer than 200 patients.

Constitution of the teams (Table 1)

Pathologies

All the studies evaluating the effect of IPC on patients with chronic diseases: patients at cardiovascular risk (28 studies), elderly and/or polypathological patients (18 studies), or patients with mental health problems (12 studies). One study addressed chronic pain related to musculoskeletal disorders [78], and 2 other studies included patients with medically unexplained complaints [77, 82]. We chose to include these studies in the same paragraph and in the same table as patients with mental health difficulties. One study included in the polypathology group evaluated criteria for monitoring comorbidities (warfarin testing compliance, eye care compliance for diabetes, etc.) and cancer screening in the general population (mammograms and occult blood screenings) [67].

Effect on patient variables

Patients at cardiovascular risk (Tables 2 and 3)

The 28 studies addressing cardiovascular risk focused particularly on diabetes (18 studies), hypertension (5 studies), overall cardiovascular risk (4 studies), or dyslipidaemia (1 study). The most common primary endpoints were glycated haemoglobin levels (14 studies), blood pressure (14 studies) and LDL-c or total cholesterol levels (9 studies). Three studies had a real morbidity criterion (cardiovascular events) as the primary endpoint, and 3 other studies assessed the number of visits to the emergency department. Fifteen studies described IPC with pharmacists, and 15 described IPC with nurses.

Interventions around cardiovascular pathologies were mainly based on team-based patient education or doctor/pharmacist collaboration (medication review, blood pressure monitoring, frequent contact about treatment by phone, through the patient's file or concertation meetings).

Of the 28 studies focusing on cardiovascular risk, five reported no significant results for their main endpoints. Benedict's study [22] which included 1960 patients, showed effects on the secondary endpoints, particularly in the short term.

The Heisler [34] cluster randomized trial focused on physician/pharmacist collaboration. It included 4100 patients but failed to show positive effects on blood pressure at 6 months, and only short-term secondary results showed a 2.4 mmHg improvement in blood pressure related to the intervention. Both groups (control and intervention) showed improvement during the study. The nonrandomized study by Manns [38] including 150,000 diabetic patients was able to show the effectiveness of the management of diabetic patients in the primary care network, with a reduction in the number of hospital and emergency department visits. Secondary analyses also showed an improvement in ophthalmological follow-up and glycaemic control. Jiao [36, 37] also showed an improvement in HbA1c levels and in the occurrence of cardiovascular events (from 2.89% to 1.21%) for the group participating in a diabetes monitoring program. These 2 studies offered network support that included many diabetes professionals: podiatrists, nurses, and dietitians.

Of the 15 studies analysing effects on glycated haemoglobin levels as the primary outcome, 10 reported positive results [21, 28,29,30,31,32,33, 36, 39, 40]. Conversely, 5 studies reported no significant effect on this variable as the primary outcome measure [22, 27, 35, 45, 49].

Among the 15 studies analysing effects on blood pressure, 10 reported positive results [23, 26, 28, 29, 31, 32, 43, 46, 48, 50]. In 3 studies the positive results were only for diastolic blood pressure, with no effect on systolic blood pressure, and one article found an improvement only in systolic pressure without improvement in diastolic blood pressure. Five studies concluded that there was no effect on blood pressure [21, 27, 34, 41, 49].

Among the 9 studies analysing an effect on cholesterol levels, 6 reported positive results while 3 concluded that there was no effect [21, 41, 49].

Elderly and/or polypathological patients (Tables 4 and 5)

The results of studies on the effect of IPC on the care of elderly or polypathological patients are inconsistent. Of the 18 studies included, 10 reported significant positive results, of which 8 were randomized controlled trials. Fifteen of these studies included doctors and nurses, after which pharmacists were the professionals most involved in care. The retrospective study by Riverin [64] associated nurses with doctors and was based on a population of 312,377 patients. The study did not demonstrate any improvement in the primary outcome measure: hospitalization 3 months after hospital discharge. It showed only a short-term decrease in the number of emergency room visits and deaths (fewer than 4 deaths per 1000 treated) in the group receiving the IPC intervention.

Eight studies did not show the effectiveness of their intervention on their primary outcome measure or variable. Eight randomized trials had documented effects. Three randomized trials [52, 55, 69] showed that the quality of care received by elderly patients was perceived as better when care was provided within the framework of a formalized collaboration among health professionals. The measurement tool in these 3 trials was the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC). The same type of result was observed in a study using the Quality of Care for Chronic Disease Management score [59].

With regard to functional abilities and patient symptoms, the randomized trial by Burns [57] showed beneficial effects of collaborative outpatient practices on patient variables relating to addiction (IADL, MMSE, maintenance of social activity) or mental health (CES-depression, general well-being, life satisfaction). The effect of IPC on hospital readmissions varied greatly among studies. Sommers et al. [66] reported a significant decrease in the number of admissions to the hospital or intensive care unit. Riverin et al. reported a decrease in the use of emergency rooms and a decrease in mortality (secondary outcome measure of the study) [64]. Conversely, some randomized trials concluded that there was no impact on their primary outcome measure [51, 53, 57, 60].

The only study focusing on cancer screening by mammograms and occult blood screenings in the general population showed better follow-up for patients followed by a health care team [67].

Patients with symptoms of mental or physical distress (Tables 6 and 7)

Among the 12 studies addressing mental health, the outcome measures sometimes included depression (10 studies), anxiety (1 study), or posttraumatic stress (1 study). Eleven studies were prospective and randomized, and 2 randomized trials included more than 1200 patients [72, 83]. Only one study did not show a significant result on the primary outcome measure [83], which was the clinical depression score at 2 years.

The evaluation of the effect of IPC treatment on psychological disorders involved various tools: the Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Scale [81], the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [73], the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [70], the Symptom checklist-core depression (SCL) [71, 72, 74], the PACIC [80], the Composite International Diagnostic Validity [83], the HSCL [71], and the Patient Health Questionnaire [79]. Often, the studies did not use validated scores but simply used the rates of cure, recourse to care or therapy use [70,71,72, 75, 76, 84].

A positive effect of the IPC intervention on patients with psychological disorders was reported in 10 studies, at least in the short term (6 months). There were no significantly positive results for 2 studies [83, 84], including that of Sherbourne, which was the only study to assess depression at 2 years. Chan's study [73] showed an improvement in the HAD score at 6 months in the intervention group, but this effect was no longer statistically significant at 12 months.

Arean et al., Engel et al. and Aragonès et al. reported an improvement in the SCL-20 score [71, 72, 74]. Four articles reported the effect of collaboration on medication compliance in depressed patients [70, 72, 75, 76], while Petersen concluded that there was no effect on compliance with these treatments [80].

Two studies were only interested in medically unexplained symptoms: that of Kolk [77] did not report a positive effect, and that of Shaefert [82] only reported an improvement in the "mental health" component of the quality of life score (SF-36) but no improvement in physical symptoms or care utilization at 12 months.

A study on musculoskeletal disorders showed that multiprofessional management involving general practitioners, occupational therapists, physiotherapists and rheumatologists significantly reduced the number of days off work: 63.8 days in the intervention group versus 92.8 days in the control group [78].

Assessment of study quality

The studies had an average quality score of 17 points (out of 28 points) using the revised Down’s and Black Checklist [min = 9, max = 21]. Eight studies had a high-quality score, 41 had a moderate-quality score, 12 had a limited-quality score (between 9 to 14 points), and no studies had a poor-quality score (< 9).

Discussion

The studies that assessed the effect of IPC on patient outcomes could be grouped into 3 categories, depending on whether the patients 1) were at cardiovascular risk, 2) were elderly and/or had polypathology, or 3) had mental or physical disorders. One study also aimed to improve prevention care. Our review of the literature did not find any studies that evaluated the effect of IPC on patient outcomes in the following fields: orthopaedics and the musculoskeletal system, cancer care, paediatrics, current infectious diseases, and patient health monitoring. Only one study analysed cancer screening in addition to monitoring comorbidities. The positive effect of IPC on patient outcomes has been widely described in patients at vascular risk. Of 28 studies, only 5 reported no significant effect on their primary outcome measures. For the 2 other categories (elderly and/or polypathological patients, patients with physical or mental disorders), the reported effects varied from one study to another. Among 18 studies that assessed the effect of IPC on the outcomes of elderly or polypathological patients, only 10 studies reported positive effects on the primary outcome measure, and 11 out of 12 reported positive effects in the category of patients with mental disorders. In this last category, 10 studies focused on patients with depressive syndrome. The majority of studies reported clinical improvement in patients. The majority of the proposed interventions relied on 3 main health professionals: general practitioners, pharmacists and nurses. Other professions were less frequently included in the studies.

In general, studies evaluating the effect of IPC are difficult to compare since the interventions are often very different, and the designs and the evaluation criteria vary, making it impossible to conduct a meta-analysis of the data. The number of studies is often very limited: many fields of care have not been the subject of any study. Some pathologies are only approached in a very isolated way, e.g., chronic pain and anxiety disorders. Finally, for the two topics best covered (cardiovascular risk and depressive syndrome), the differences among the studies remain significant and limit the opportunity to aggregate the results. It is notable that the judgement outcomes are also very different. Compliance [44], patient satisfaction [42], or improvement in blood pressure or HbA1c levels [25, 29] cannot be compared. Finally, even when the studies analysed a bioclinical measure such as HbA1C levels, the authors chose different judgement criteria: the rate of prescription of an examination [51], the examination completion rate [30, 40, 49], the variation of the result over time or the rate of patients reaching their objective for this measure [22]. This complicates the comparison of studies. Smith did not show any effectiveness of his intervention on the HbA1c level in diabetic patients (the primary outcome measure) but showed that the proportion of patients who carried out the recommended monitoring examinations had increased [45]. For the 15 studies evaluating the effect of ICP on arterial hypertension, the diversity of judgement outcomes still remains significant, depending on whether the authors chose to analyse the mean systolic blood pressure value in the intervention arm [29], the change in systolic blood pressure over one year [34, 43], the change in diastolic blood pressure over one year [36], the proportion of patients with controlled systolic blood pressure (less than 140 mmHg) [43], the proportion of patients for whom the systolic blood pressure was measured (care procedure indicator) [26], the proportion of patients for whom an anti-hypertensive treatment dose adjustment was carried out [44], the evolution of the mean 24-h SBP [24], or the evolution of the SBP at home [48].

The clinical impact of the effects observed can also be questioned. For example, the study by Heisler [34], a large randomized study (4100 patients), showed a reduction of 2.4 mmHg in blood pressure thanks to the help of the pharmacist, which is clinically limited. With regard to depression, one can wonder about the benefit of a 3.6-point reduction in the Hamilton score for patients, even if the result is statistically significant [81].

As in other studies, we found that GPs, nurses and pharmacists were the most represented professionals in the IPC teams in the primary care setting [11, 85].

Several authors have shown that IPC would increases patient use and costs of care [86]. These indicators of the use and costs of the health care system are important from the perspective of the decision-maker, but they must be interpreted with caution. On the one hand, less use of to the health care system can testify to better individual health with lower morbidity (a reduction in the number of visits to the emergency room for example, or a reduction in the number of hospitalizations) [38, 66, 87]. On the other hand, these indicators can also attest to a positive effect with regard to issues of compliance and improvement of patient health: in many patients with chronic diseases monitored in primary care, the recommendations emphasize the prevention of serious events through the implementation of reinforced medical monitoring, resulting in an increase in the use of health care system by patients. Thus, the increase in the number of consultations with a health care professional may be appropriate during a period of antihypertensive treatment dosage adjustment to allow the achievement of the objectives [29].

Strengths and limitations

This literature review has several strengths. First, it is the first to identify in a transversal way in which fields the effect of IPC has been analysed and in which fields this effect has been demonstrated. In 2020, Pascucci carried out a literature review and a meta-analysis on the subject, but without restricting its research equation to the primary care setting and only focusing on patients with chronic pathologies [88]. It concluded that IPC would improve the 3 following cardiovascular outcomes: BP, HbA1c levels, and the number of days of hospitalization in patients undergoing the IPC intervention. Second, our systematic review was based on the PRISMA quality guidelines; the research was carried out in 4 databases. Third, we assume that the focus on studies conducted in a primary care setting, involving primary care providers exclusively, might be a strength, while previous authors focused on the collaborations between primary and secondary care professionals.

This review also has limitations. The formalization of the search equation leading to the selection of studies required tedious work since there is no published search filter to search for articles addressing IPCs. It might be the main limitation of this review. Future work should consist of a specific and sensitive search filter developed by researchers in the field.

It was not possible to perform a bias analysis with the iCROMs [89] tool because the designs of the studies were too disparate. The quality of the studies was therefore assessed using the revised Downs and Black Checklist [18].

Effective studies are probably overrepresented compared to ineffective studies due to publication bias [90]. Similarly, many studies presented significant results but were based on post hoc or subgroup analyses.

The low level of evidence of clinical efficacy may be linked to the low level of internal validity of these studies, which are mainly pragmatic clinical trials [91, 92]. These trials are complex and therefore give positive results with greater difficulty.

In our review, the analysis of the differences between the control group and the multiprofessional intervention groups may have been biased by the fact that the primary care teams studied set up collaborative actions based on different concepts, e.g., the use of information technology, the training of health professionals or the therapeutic education of patients. Therefore, it is sometimes impossible to differentiate for these interventions whether the demonstrated effect is linked to the action implemented by a tool or solely by the IPC.

The concrete typology and level of collaboration among professionals differs greatly from one team to another, and this aspect was not the focus of our research. We therefore chose to describe IPC from the perspective of the most common definition and real life practice [8] without detailing the interactions involved in collaboration or its level. The type and level of interaction within the IPC teams depends on local contexts, dependent on national support for primary care and IPC [8, 9]. Reviews have already confirmed that, in this context and in the absence of new work on the subject, it is difficult to find a consensual definition of the typology of IPC [9, 11].

Perspective

Primary care research within the framework of IPC must be able to invest in the field of primary prevention and screenings; currently, IPC is underrepresented in the fields of chronic diseases, cancers, vaccination, addictions, etc., as well as some fields mentioned above (locomotor, oncology) that have not benefited or in which little research with a high level of evidence exists. These areas have already been explored and described in the literature, but not with a comparative trial evaluation in the specific field of IPC in primary care. Our focus was quite narrow and doesn’t give a wide picture of the IPC in primary care.

The interventions offered to patients are often well described in the articles, but the description of the type of professionals and their levels of collaboration is often limited. For example, a patient will be able to benefit from an exchange regarding his pathology and treatment with a pharmacist, who will make recommendations that will be discussed with the doctor, but exchanges between health professionals are insufficiently described in terms of the methods, duration, and frequencies of interactions [43].

Further work should focus on the intensity of IPC and the elements needed to achieve effective IPC. The following organizational elements are necessary: health policies structuring primary care and funding the time needed to work together, networks with local governance, secure and shared IT systems for working together on patient records, trainings for primary care teams to learn how to work together in confidence without losing sight of the patient's objectives [93].

Some studies, such as that of Benedict in 2018, showed an improvement in the primary outcome measure in the short term (3 or 6 months) without long-term maintenance [22]. As multiprofessional primary care teams have to deal with an increasing number of patients with chronic pathologies, it would therefore be logical to hope for a long-term effect of these interventions: studies with longer period of follow-up would be needed in this context.

Conclusion

Many studies have shown that IPC can improve the management of patients at cardiovascular risk. Other studies have investigated the effect of IPC in polypathological elderly patients and in patients with mental or physical disorders. For these pathologies, the number of studies remains limited, and the results are heterogeneous. Researchers should be encouraged to perform studies based on comparative designs: it would increase evidence on the positive effect and benefits of IPC on patient variables.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Adj:

-

Adjusted

- C:

-

Control group

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DBP:

-

Diastolic Blood Pression

- HSCL score:

-

Hopkins Symptom Checklist score

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- I:

-

Intervention Group

- IPC:

-

Interprofessional Collaboration

- LDL-c:

-

Low Density Lipoprotein cholesterol

- OR:

-

Odds-Ratio

- MPR:

-

Medication Possession Ratio

- MSDs:

-

Musculoskeletal Disorders

- NRd:

-

Not Randomized

- NS:

-

Not Significant

- P:

-

Prospective

- PACIC:

-

Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care

- PTSD:

-

Post traumatic stress disorder

- R:

-

Retrospective

- Rd:

-

Randomised

- Rd C:

-

Randomised in Cluster

- SBP:

-

Systolic Blood Pression

- SCL:

-

Symptom Checklist-core depression

References

World Health Organization, Fund (UNICEF) UNC. A vision for primary health care in the 21st century: towards universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals. World Health Organization. 2018. Report No.: WHO/HIS/SDS/2018.15. Disponible sur: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/328065. Cité 6 déc 2022.

White KL. The ecology of medical care: origins and implications for population-based healthcare research. Health Serv Res. 1997;32(1):11–21.

Green LA, Fryer GE Jr, Yawn BP, Lanier D, Dovey SM. The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(26):2021–5.

Kirkwood J, Ton J, Korownyk CS, Kolber MR, Allan GM, Garrison S. Who provides chronic Disease management? Population-based retrospective cohort study in Alberta. Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. 2023;69(6):e127-133.

Džakula A, Relić D, Michelutti P. Health workforce shortage – doing the right things or doing things right? Croat Med J. 2022;63(2):107–9.

Law 2009 − 879 21 july 2009 portant réforme de l’hôpital et relative aux patients, à la santé et aux territoires: JORF n°0167 du 22 juillet 2009. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000020879475.

Wranik WD, Price S, Haydt SM, Edwards J, Hatfield K, Weir J, et al. Implications of interprofessional primary care team characteristics for health services and patient health outcomes: a systematic review with narrative synthesis. Health Policy. 2019;123(6):550–63.

Gilbert JHV, Yan J, Hoffman SJ. A WHO report: framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. J Allied Health. 2010;39(Suppl 1):196–7.

Reeves S, Pelone F, Harrison R, Goldman J, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2017(6):CD000072.

Dahlke S, Hunter KF, Reshef Kalogirou M, Negrin K, Fox M, Wagg A. Perspectives about interprofessional collaboration and patient-centred care. Can J Aging Rev Can Vieil. 2020;39(3):443–55.

Saint-Pierre C, Herskovic V, Sepúlveda M. Multidisciplinary collaboration in primary care: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2018;35(2):132–41.

Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, Lovell K, Richards D, Gask L, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525.

Johnson JM, Carragher R. Interprofessional collaboration and the care and management of type 2 diabetic patients in the Middle East: a systematic review. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(5):621–8.

Li M, Kennedy EB, Byrne N, Gérin-Lajoie C, Katz MR, Keshavarz H, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of collaborative care interventions for depression in patients with cancer. Psychooncology. 2017;26(5):573–87.

Lee JK, McCutcheon LRM, Fazel MT, Cooley JH, Slack MK. Assessment of Interprofessional collaborative practices and outcomes in adults with diabetes and hypertension in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2036725.

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160.

Rathbone J, Hoffmann T, Glasziou P. Faster title and abstract screening? Evaluating Abstrackr, a semi-automated online screening program for systematic reviewers. Syst Rev. 2015;4:80.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–84.

Huffer D, Hing W, Newton R, Clair M. Strength training for plantar fasciitis and the intrinsic foot musculature: a systematic review. Phys Ther Sport off J Assoc Chart Physiother Sports Med. 2017;24:44–52.

Agarwal G, Gaber J, Richardson J, Mangin D, Ploeg J, Valaitis R, et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of a complex intervention for Diabetes self-management supported by volunteers, technology, and interprofessional primary health care teams. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019;27(1):118.

Barceló A, Cafiero E, de Boer M, Mesa AE, Lopez MG, Jiménez RA, et al. Using collaborative learning to improve Diabetes care and outcomes: the VIDA project. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4(3):145–53.

Benedict AW, Spence MM, Sie JL, Chin HA, Ngo CD, Salmingo JF, et al. Evaluation of a pharmacist-managed diabetes program in a primary care setting within an integrated health care system. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(2):114–22.

Carter BL, Ardery G, Dawson JD, James PA, Bergus GR, Doucette WR, et al. Physician and pharmacist collaboration to improve blood pressure control. Arch Intern Med. 2009;23(21):1996–2002.

Chen Z, Ernst ME, Ardery G, Xu Y, Carter BL. Physician-pharmacist co-management and 24-hour blood pressure control. J Clin Hypertens Greenwich Conn. 2013;15(5):337–43.

Carter BL, Coffey CS, Ardery G, Uribe L, Ecklund D, James P, et al. Cluster-randomized trial of a physician/pharmacist collaborative model to improve blood pressure control. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(3):235–43.

Carter BL, Levy B, Gryzlak B, Xu Y, Chrischilles E, Dawson J, et al. Cluster-Randomized Trial to Evaluate a Centralized Clinical Pharmacy Service in Private Family Medicine Offices. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(6). Disponible sur: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.004188. Cité 7 déc 2021.

Chen EH, Thom DH, Hessler DM, Phengrasamy L, Hammer H, Saba G, et al. Using the teamlet model to improve chronic care in an academic primary care practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(Suppl 4):610–4.

Choi YK, Han JH, Li R, Kung K, Lam A. Implementation of secondary stroke prevention protocol for ischaemic stroke patients in primary care. Hong Kong Med J. 2015;21(2):136–42.

Chwastiak LA, Jackson SL, Russo J, DeKeyser P, Kiefer M, Belyeu B, et al. A collaborative care team to integrate behavioral health care and treatment of poorly-controlled type 2 Diabetes in an urban safety net primary care clinic. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;44:10–5.

Edwards HD, Webb RD, Scheid DC, Britton ML, Armor BL. A pharmacist visit improves Diabetes standards in a patient-centered medical home (PCMH). Am J Med Qual. 2012;27(6):529–34.

ElGerges NS. Effects of therapeutic education on self-efficacy, self-care activities and glycemic control of type 2 diabetic patients in a primary healthcare center in Lebanon. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2020;19(2):813–21.

Fokkens AS, Wiegersma PA, Beltman FW, Reijneveld SA. Structured primary care for type 2 Diabetes has positive effects on clinical outcomes. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(6):1083–8.

Furler J, O’Neal D, Speight J, Manski-Nankervis JA, Gorelik A, Holmes-Truscott E, et al. Supporting insulin initiation in type 2 diabetes in primary care: results of the Stepping Up pragmatic cluster randomised controlled clinical trial. BMJ. 2017;356:j783.

Heisler M, Hofer TP, Schmittdiel JA, Selby JV, Klamerus ML, Bosworth HB, et al. Improving blood pressure control through a clinical pharmacist outreach program in patients with diabetes mellitus in 2 high-performing health systems: the adherence and intensification of medications cluster randomized, controlled pragmatic trial. Circulation. 2012;125(23):2863–72.

Jameson JP, Baty PJ. Pharmacist collaborative management of poorly controlled Diabetes Mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(4):250–5.

Jiao FF, Fung CSC, Wong CKH, Wan YF, Dai D, Kwok R, et al. Effects of the multidisciplinary Risk Assessment and Management Program for patients with Diabetes Mellitus (RAMP-DM) on biomedical outcomes, observed cardiovascular events and cardiovascular risks in primary care: a longitudinal comparative study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:127.

Jiao F, Fung CSC, Wan YF, McGhee SM, Wong CKH, Dai D, et al. Long-term effects of the multidisciplinary risk assessment and management program for patients with Diabetes Mellitus (RAMP-DM): a population-based cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2015;14(1):105.

Manns BJ, Tonelli M, Zhang J, Campbell DJT, Sargious P, Ayyalasomayajula B, et al. Enrolment in primary care networks: impact on outcomes and processes of care for patients with Diabetes. CMAJ. 2012;184(2):E144-152.

McAdam-Marx C, Dahal A, Jennings B, Singhal M, Gunning K. The effect of a diabetes collaborative care management program on clinical and economic outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(6):452–68.

Mousquès J, Bourgueil Y, Le Fur P, Yilmaz E. Effect of a French experiment of team work between general practitioners and nurses on efficacy and cost of type 2 Diabetes patients care. Health Policy Amst Neth. 2010;98(2–3):131–43.

Mundt MP, Gilchrist VJ, Fleming MF, Zakletskaia LI, Tuan WJ, Beasley JW. Effects of Primary care team social networks on quality of care and costs for patients with cardiovascular disease. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):139–48.

Pape GA, Hunt JS, Butler KL, Siemienczuk J, LeBlanc BH, Gillanders W, et al. Team-based care approach to cholesterol management in diabetes mellitus: two-year cluster randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;12(16):1480–6.

Simpson SH, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Lewanczuk RZ, Spooner R, Johnson JA. Effect of adding pharmacists to primary care teams on blood pressure control in patients with type 2 Diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):20–6.

Omran D, Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, Tsuyuki RT, Lewanczuk RZ, Guirguis LM, et al. Pharmacists on primary care teams: Effect on antihypertensive medication management in patients with type 2 Diabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc JAPhA. 2015;55(3):265–8.

Smith S, Bury G, O’Leary M, Shannon W, Tynan A, Staines A, et al. The North Dublin randomized controlled trial of structured diabetes shared care. Fam Pract. 2004;21(1):39–45.

Smith SM, Wallace E, O’Dowd T, Fortin M. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD006560.

Tahaineh L, Albsoul-Younes A, Al-Ashqar E, Habeb A. The role of clinical pharmacist on lipid control in dyslipidemic patients in North of Jordan. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(2):229–36.

Tobari H, Arimoto T, Shimojo N, Yuhara K, Noda H, Yamagishi K, et al. Physician-pharmacist cooperation program for blood pressure control in patients with hypertension: a randomized-controlled trial. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23(10):1144–52.

Vitale M, Xu C, Lou W, Horodezny S, Dorado L, Sidani S, et al. Impact of diabetes education teams in primary care on processes of care indicators. Prim Care Diabetes. 2020;14(2):111–8.

Weber CA, Ernst ME, Sezate GS, Zheng S, Carter BL. Pharmacist-physician comanagement of hypertension and reduction in 24-hour ambulatory blood pressures. Arch Intern Med. 2010;11(18):1634–9.

Aigner MJ, Drew S, Phipps J. A comparative study of nursing home resident outcomes between care provided by nurse practitioners/physicians versus physicians only. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5(1):16–23.

Boult C, Reider L, Frey K, Leff B, Boyd CM, Wolff JL, et al. Early effects of “Guided Care” on the quality of health care for multimorbid older persons: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(3):321–7.

Leff B, Reider L, Frick KD, Scharfstein DO, Boyd CM, Frey K, et al. Guided care and the cost of complex healthcare: a preliminary report. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(8):555–9.

Boult C, Reider L, Leff B, Frick KD, Boyd CM, Wolff JL, et al. The effect of guided care teams on the use of health services: results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):460–6.

Boyd CM, Reider L, Frey K, Scharfstein D, Leff B, Wolff J, et al. The effects of guided care on the Perceived quality of health care for multi-morbid older persons: 18-month outcomes from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):235–42.

Brown L, Tucker C, Domokos T. Evaluating the impact of integrated health and social care teams on older people living in the community. Health Soc Care Community. 2003;11(2):85–94.

Burns R, Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J, Graney MJ. Interdisciplinary geriatric primary care evaluation and management: two-year outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(1):8–13.

Dolovich L, Oliver D, Lamarche L, Thabane L, Valaitis R, Agarwal G, et al. Combining volunteers and primary care teamwork to support health goals and needs of older adults: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Can Med Assoc J. 2019;191(18):E491-500.

Hogg W, Lemelin J, Dahrouge S, Liddy C, Armstrong CD, Legault F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of anticipatory and preventive multidisciplinary team care: for complex patients in a community-based primary care setting. Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. 2009;55(12):e76-85.

Lenaghan E, Holland R, Brooks A. Home-based medication review in a high risk elderly population in primary care–the POLYMED randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing Mai. 2007;36(3):292–7.

Lin EHB, Von Korff M, Peterson D, Ludman EJ, Ciechanowski P, Katon W. Population targeting and durability of multimorbidity collaborative care management. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(11):887–95.

Matzke GR, Moczygemba LR, Williams KJ, Czar MJ, Lee WT. Impact of a pharmacist–physician collaborative care model on patient outcomes and health services utilization. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(14):1039–47.

Melis RJF, van Eijken MIJ, Teerenstra S, van Achterberg T, Parker SG, Borm GF, et al. A randomized study of a multidisciplinary program to intervene on geriatric syndromes in vulnerable older people who live at home (Dutch EASYcare study). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(3):283–90.

Riverin BD, Li P, Naimi AI, Strumpf E. Team-based versus traditional primary care models and short-term outcomes after hospital discharge. Can Med Assoc J. 2017;189(16):E585-593.

Sellors J, Kaczorowski J, Sellors C, Dolovich L, Woodward C, Willan A, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a pharmacist consultation program for family physicians and their elderly patients. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc Medicale Can. 2003;169(1):17–22.

Sommers LS, Marton KI, Barbaccia JC, Randolph J. Physician, nurse, and social worker collaboration in primary care for chronically ill seniors. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(12):1825–33.

Taplin S, Galvin MS, Payne T, Coole D, Wagner E. Putting population-based care into practice: real option or rhetoric? J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11(2):116–26.

van Lieshout MRJ, Bleijenberg N, Schuurmans MJ, de Wit NJ. The effectiveness of a PRoactive multicomponent intervention program on disability in independently living older people: a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22(9):1051–9.

Wolff JL, Giovannetti ER, Boyd CM, Reider L, Palmer S, Scharfstein D, et al. Effects of guided care on family caregivers. The Gerontologist. 2010;50(4):459–70.

Adler DA, Bungay KM, Wilson IB, Pei Y, Supran S, Peckham E, et al. The impact of a pharmacist intervention on 6-month outcomes in depressed primary care patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26(3):199–209.

Aragonès E, Rambla C, López-Cortacans G, Tomé-Pires C, Sánchez-Rodríguez E, Caballero A, et al. Effectiveness of a collaborative care intervention for managing major depression and chronic musculoskeletal pain in primary care: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2019;252:221–9.

Areán PA, Gum AM, Tang L, Unützer J. Service use and outcomes among elderly persons with low incomes being treated for depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(8):1057–64.

Chan WS, Whitford DL, Conroy R, Gibney D, Hollywood B. A multidisciplinary primary care team consultation in a socio-economically deprived community: an exploratory randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:15.

Engel CC, Jaycox LH, Freed MC, Bray RM, Brambilla D, Zatzick D, et al. Centrally assisted collaborative telecare for posttraumatic stress disorder and depression among military personnel attending primary care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):948–56.

Finley PR, Rens HR, Pont JT, Gess SL, Louie C, Bull SA, et al. Impact of a collaborative pharmacy practice model on the treatment of depression in primary care. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2002;59(16):1518–26.

Finley PR, Rens HR, Pont JT, Gess SL, Louie C, Bull SA, et al. Impact of a collaborative care model on depression in a primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(9):1175–85.

Kolk AMM, Schagen S, Hanewald GJFP. Multiple medically unexplained physical symptoms and health care utilization: outcome of psychological intervention and patient-related predictors of change. J Psychosom Res oct. 2004;57(4):379–89.

Marklund B, Månsson J, Anderberg CP, Hagberg K, Lyder I, Bengtsson C, et al. Effects on Sickness Pattern of Early Mini-rehabilitation Groups Among Patients with Musculoskeletal Problems in Primary Healthcare. Scand J Occup Ther. 1999;6(2):90–4.

Morgan MAJ, Coates MJ, Dunbar JA, Reddy P, Schlicht K, Fuller J. The TrueBlue model of collaborative care using practice nurses as case managers for depression alongside diabetes or heart disease: a randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1). Disponible sur: http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=84873473869&partnerID=8YFLogxK. Cité 13 août 2022.

Petersen JJ, König J, Paulitsch MA, Mergenthal K, Rauck S, Pagitz M, et al. Long-term effects of a collaborative care intervention on process of care in family practices in Germany: a 24-month follow-up study of a cluster randomized controlled trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(6):570–4.

Rollman BL, Belnap BH, Mazumdar S, Houck PR, Zhu F, Gardner W, et al. A randomized trial to improve the quality of treatment for panic and generalized anxiety disorders in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry déc. 2005;62(12):1332–41.

Schaefert R, Kaufmann C, Wild B, Schellberg D, Boelter R, Faber R, et al. Specific collaborative group intervention for patients with medically unexplained symptoms in general practice: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2013;82(2):106–19.

Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Duan N, Miranda J, Unützer J, Jaycox L, et al. Long-term effectiveness of disseminating quality improvement for depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(7):696–703.

Simon GE, Katon W, Rutter C, VonKorff M, Lin E, Robinson P, et al. Impact of improved depression treatment in primary care on daily functioning and disability. Psychol Med Mai. 1998;28(3):693–701.

Carron T, Rawlinson C, Arditi C, Cohidon C, Hong QN, Pluye P, et al. An overview of reviews on interprofessional collaboration in primary care: effectiveness. Int J Integr Care. 2021;21(2):31.

van Steenbergen-Weijenburg KM, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Horn EK, van Marwijk HWJ, Beekman ATF, Rutten FFH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for the treatment of major depressive disorder in primary care. A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:19.

Mason A, Goddard M, Weatherly H, Chalkley M. Integrating funds for health and social care: an evidence review. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2015;20(3):177–88.

Pascucci D, Sassano M, Nurchis MC, Cicconi M, Acampora A, Park D, et al. Impact of interprofessional collaboration on chronic disease management: findings from a systematic review of clinical trial and meta-analysis. Health Policy Amst Neth févr. 2021;125(2):191–202.

Zingg W, Castro-Sanchez E, Secci FV, Edwards R, Drumright LN, Sevdalis N, et al. Innovative tools for quality assessment: integrated quality criteria for review of multiple study designs (ICROMS). Public Health. 2016;133:19–37.

Mlinarić A, Horvat M, Šupak Smolčić V. Dealing with the positive publication bias: why you should really publish your negative results. Biochem Med. 2017;27(3):030201.

Schwartz D, Lellouch J. Explanatory and pragmatic attitudes in therapeutical trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):499–505.

Godwin M, Ruhland L, Casson I, MacDonald S, Delva D, Birtwhistle R, et al. Pragmatic controlled clinical trials in primary care: the struggle between external and internal validity. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3: 28.

Rawlinson C, Carron T, Cohidon C, Arditi C, Hong QN, Pluye P, et al. An overview of reviews on interprofessional collaboration in primary care: barriers and facilitators. Int J Integr Care. 2021;21(2):32.

Acknowledgements

We thank Solène Girard, Adam Mouhib, Antoine Nogueira, and Louise Rouxel for their help during the data collection. This article is supported by the French network of University Hospitals HUGO (‘Hôpitaux Universitaires du Grand Ouest’).

Funding

The study was funded by the French Ministry of Health. The research team members were independent from the Ministry. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CB and CR were responsible for conducting the systematic review, including the interpretation of the results and the drafting of the full report of the systematic review. MJn, MA, JFH conducted the search and data extraction. MJx contributed to the data analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript prior submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Revised Downs and Black checklist for assessment of methodological quality.

Additional file 2.

Assessment of studies quality.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bouton, C., Journeaux, M., Jourdain, M. et al. Interprofessional collaboration in primary care: what effect on patient health? A systematic literature review. BMC Prim. Care 24, 253 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02189-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02189-0