Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization supports interprofessional collaboration in primary care. On over the past 20 years, community pharmacists had been taking a growing number of new responsibilities and they are recognized as a core member of collaborative care teams as patient-centered care providers. This systematic review aimed to describe interprofessional collaboration in primary care involving a pharmacist, and its effect on patient related outcomes.

Methods

A systematic review of randomized controlled trials cited in the MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycInfo and CINAHL in English and French was conducted from inception to November 2022. Studies were included if they described an intervention piloted by a primary care provider and included a pharmacist and if they evaluated the effects of intervention on a disease or on patient related outcomes. The search generated 3494 articles. After duplicates were removed and titles and abstracts screened for inclusion, 344 articles remained.

Results

Overall, 19 studies were included in the review and assessed for quality. We found 14 studies describing an exclusive collaboration between physician and pharmacist with for all studies a three-step model of pharmacist intervention: a medication review, an interview with the patient, and recommendations made to physician. Major topics in the articles eligible for inclusion included cardiovascular diseases with blood pressure, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and risk of cardiovascular diseases. Positive effects concerned principally blood pressure.

Conclusions

Collaboration involving pharmacists is mainly described in relation to cardiovascular diseases, for which patient-centered indicators are most often positive. It underscores the need for further controlled studies on pharmacist-involved interprofessional collaboration across various medical conditions to improve consensus on core outcomes measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Health Organization supports interprofessional collaboration in primary care [1]. Interprofessional collaboration is defined as multiple health professionals from different backgrounds working together with patients, their families, carers and communities to deliver high quality patient-centered care [1]. In primary care, interprofessional collaboration has been shown to improve patient pathways, healthcare efficiency and cost-effectiveness [2,3,4], and job satisfaction for healthcare providers [5, 6].

Delegating healthcare responsibilities to pharmacists in the context of interprofessional collaboration is one aspect of healthcare that has been adapted to meet the increasing demands and needs to access safe and effective healthcare [5, 7]. This became particularly necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic when interprofessional collaboration rapidly developed to support severely challenged healthcare systems worldwide [8]. To address the heightened strain on healthcare resources, several countries have restructured emergency medical services and reassigned healthcare professional responsibilities [9]. This includes the participation of community pharmacists in COVID-19 screening and vaccination [10, 11]. These additional responsibilities further expanded the growing number of new responsibilities that pharmacists had been taking on over the past 20 years. They include screening for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [12], diabetes [13], or cancer [14, 15], prescribing medication (initiation, continuation or modification) [16,17,18] and reviewing and monitoring prescribing guidelines [19].

To date, some reviews have investigated interprofessional collaborations in healthcare [20, 21]. However, little information is available in the literature about the effects of pharmacist involvement in interprofessional collaboration in primary care, and how it is organized. This systematic review aimed to describe interprofessional collaboration in primary care involving a pharmacist, and its effect on disease or patient related outcome.

Method

This systematic review was performed according to PRISMA guidelines [22], using MEDLINE (Pubmed), EMBASE, PsycInfo and CINAHL from inception to July 2021. Subsequently, an abbreviated MEDLINE search update from July 2021 to November 2022 was performed. This review constitutes a secondary analysis of a systematic review conducted on interprofessional collaborations in primary care [23].

The following search strategy was used in PubMed: (“Intersectoral Collaboration“[Mesh] OR “Cooperative Behavior“[Mesh] OR “Patient Care Team“[Mesh:NoExp]) AND (“Primary Health Care“[Mesh]) AND (“Outcome and Process Assessment, Health Care“[Mesh]). “This search strategy was adapted to the syntax of Embase, PsychINFO, and CINHAL databases: “intersectoral collaboration”, “cooperative behavior”, “patient care team” AND “primary health care” AND “outcome and process assessment, health care”. The details concerning the search strategy were presented in Supplementary material 1.

To be included, a study had to have reported a randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the effects of a pharmacist intervention on a disease or patient related outcome. The intervention had to be in the context of interprofessional collaboration, which was piloted by a primary care provider and published in English or French. Studies were excluded if they did not report interprofessional collaboration and if they were not in IMRAD format.

Four reviewers (SG, LR, AN and AM) screened the titles and abstracts of the database records and retrieved the full texts and independently examined the studies for eligibility. Disagreements were resolved by consensus discussion with three reviewers (MJ, MA, JFH). The reference lists of included studies were hand searched for additional citations. In a second stage, given the large number of articles, only articles involving a pharmacist were selected.

From those studies included, data concerning the study (authors, publication date, country, sample size, objective and pathology, study duration, inclusion criteria), the intervention (professionals involved, intervention type or practice collaboration), and measures to assess the intervention effect (main outcome measure, secondary outcomes) were extracted.

Two independent reviewers (MA, JFH) appraised the risk of bias and quality of each included study using the Integrated Quality Criteria for Review of Multiple Study Designs (ICROMS) tool [24].

The systematic review was registered in PROSPERO under number CRD42021278461. The registered protocol substantially differs from the review methods. We have focused on pharmacist interventions and presented only results on the effects of interprofessional collaboration on patients to enhance clarity. We have increased reviewers from two to four to address the paper volume.”

Results

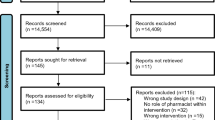

Figure 1 presents the PRISMA Flow Diagram. In total, 3472 records were identified of which 2242 were excluded. The excluded studies were interventions delivered by a secondary care professional or did not investigate interprofessional collaboration. Then, 1230 abstracts and 344 full text papers were screened for eligibility and 19 were included in the review.

Study characteristics

Table 1 lists the study characteristics. Among the 19 studies included, most were performed in North America (n = 16), only two in Asia and one in Europe. A majority (n = 14) were published in 2009 or later [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], the oldest study (Finley et al.) was published in 2002 [39]. Eight studies evaluated a collaborative pharmacist intervention for six months [25, 28, 32, 36, 37, 39,40,41] and eight studies for more than 12 months [26, 27, 29,30,31, 33, 34, 42]. The median follow-up time was 9 months. Median study sample size was 260 ranging from 104 to 6963 participants.

Characteristics of pharmacist intervention

Supplementary material 2 lists the characteristics of pharmacist intervention. Most studies investigated a collaborative intervention involving only a physician and a pharmacist [25,26,27,28,29, 32, 33, 35,36,37,38, 41,42,43]. Two studies involved a physician, a pharmacist, and a nurse [30, 31]. Three studies involved a pharmacist and an allied health team consisting of physicians, nurses, dietitians, psychotherapists, care managers, social workers or psychiatrists [34, 39, 40].

Overall, the pharmacist intervention typically involved medication review, patient interviews, and recommendations to physicians. The medication review was performed using data recorded in an electronic medical record database, then completed with a telephone or face-to-face patient interview [26, 34,35,36, 38, 39, 43]. One study involved nurses who developed an individualized care plan with the patient and in consultation with the pharmacist and the physician [30]. The frequency of clinical contact with patients varied from 2 [41, 43] to 12 or more contacts [27]. The physician was free to accept or reject pharmacist recommendations except in one study where the pharmacist had the authorization to directly modify medications, and the physician was solely informed [29]. In all the other studies, recommendations to physicians were provided either during face-to-face contact [25, 26, 28, 37, 41,42,43], or by telephone [37, 40, 42] or email [26, 27, 29, 33, 35, 39, 42, 43]. The acceptance rate for pharmacist interventions was reported in seven studies and was between 76.6% and 96.2% [25, 27, 28, 33, 36, 38, 43].

However, three studies, also assessed additional activities combined with the typical pharmacist intervention. Heisler et al. (2012), investigated an intervention in which the pharmacist suggested and prescribed treatment changes directly to the patient [29]. Three studies investigated a pharmacist intervention that involved taking clinical measurements (blood pressure, heart rate or weight) and laboratory tests [25, 29, 34].

In all studies, participants in the control group did not benefit from pharmacist intervention; instead, they were exclusively received usual care from physicians alone [25,26,27,28,29, 31, 33, 35,36,37,38, 40, 41, 43] or from primary care teams composed on physicians and nurses [30, 32, 34, 39, 42].

Effect of pharmacist intervention on patient-related outcomes

Figure 2 illustrates the various conditions in which the pharmacist intervention was investigated. Of the 19 studies included, 13 involved patients with cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension [25,26,27,28,29, 35, 37, 38], diabetes [27, 29, 31,32,33,34] and/or dyslipidemia [27, 36]). Three studies included patients with depression [39, 40, 42] and three studies included elderly people with multiple chronic diseases [30, 41, 43].

Table 2 lists the outcome measures and significant results studied for the various pathologies. We found that the effect of pharmacist intervention varied depending on the outcome measure and follow-up duration. In supplementary material 3, a table lists the outcome measures and significant and non-significant results.

Concerning blood pressure reduction, most studies reported that the pharmacist intervention significantly lowered blood pressure [25, 26, 28, 34, 35, 37, 38] with a follow-up duration ranging from 6 to 12 months. Four studies did not report any effect [27, 29, 30, 33]. Concerning blood pressure control, defined as blood pressure measured lower than 130/80 mmHg for patients with diabetes mellitus or chronic disease and lower than 140/90 for all other patients, two studies found pharmacist intervention had a positive effect [25, 28] and four studies did not find any effect [26, 27, 35, 37].

Seven studies measured glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels [29, 31,32,33,34,35,36]. However, only one study reported finding significantly improved HbA1c levels following a pharmacist intervention, among males and ethnic minority subgroups [31].

Concerning pharmacist interventions to reduce cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, Simpson et al. (2011) reported a significant reduction of 1.5% (95% CI -0.2 to 3.3) in predicted 10-year cardiovascular event risk [34]. More specifically, Tobari et al. (2010) reported lower Body Mass Index (BMI), sodium score and fewer smokers, but no effect was demonstrated among patients with alcohol consumption > 23 g/day or with brisk walking > 30 min/day [37].

Furthermore, among those interventions to control dyslipidemia [27, 29, 33, 34, 36], two studies reported that pharmacist intervention resulted in significantly lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) after 6 or 24 months [33, 36] and total cholesterol after 6 months [36] but three studies did not demonstrate any effect [27, 29, 34].

Two studies focused on depressive disorders with one showing that patients expressed greater satisfaction than controls with a pharmacist intervention but neither reported an effect of pharmacist intervention on patient related outcome [40, 42].

Five studies evaluated medication adherence [25, 32, 35, 39, 40], two of which reported a positive effect of pharmacist intervention on patient adherence to medication, including a post-hoc analysis among an ethnic minority group [35, 39]. Three studies did not report significant results [25, 32, 40].

None of the three studies identified demonstrated an effect of pharmacist intervention on the quality of life in older people [30, 41, 43].

For the studies evaluating the pharmacist role in preventative medicine, a positive effect was observed for influenza vaccination, colorectal cancer screening, hearing and eye examination [30], BMI screening and follow-up and alcohol use [27]. However, no effect was observed on breast and cervical cancer screening [30], diabetic foot examination, dilated eye examination, microalbumin measurement and proportion of smokers advised to quit [27]. Pape et al. (2011) found that a higher proportion of patients underwent a LDL-C test in the intervention group [33].

Lastly, a positive effect of pharmacist intervention was observed in an interprofessional collaboration. Patients appreciated the personal nature of care, provider availability, provider ability to listen, explanation of why antidepressants were prescribed, and the explanation of how to take the antidepressants and, overall, patients were satisfied with the pharmacist intervention [39, 40]. Pape et al. (2011) did not find significant results [33].

Fig. 3 provides a synthesized overview of the evidence pertaining on interprofessional collaboration

Critical appraisal of studies

According to the ICROMS quality assessment, six studies had a low risk of bias [30, 31, 33, 34, 37, 41], meeting both minimum score and mandatory criteria. Nine studies had a moderate risk of bias; minimum ICROMS scores were met but mandatory scores were not [25,26,27,28,29, 35, 38, 40, 43]. The remaining four studies had a high risk of bias, with neither minimum or mandatory scores being met [32, 36, 39, 42]. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Discussion

This systematic review identified 19 randomized controlled trials evaluating the effects of pharmacist interventions in primary care conducted in various countries and different health care settings. Most studies concerned a physician-pharmacist collaboration and only five studies included a physician and other health professionals. All studies included a standard pharmacist intervention involving medication review, patient interview, and recommendations to the physician. However, three studies also included additional responsibilities. Interestingly we found an over-representation of RCTs among patients with cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia. Only six studies evaluated pharmacist involvement in interprofessional collaboration among patients with other pathologies and with mixed results.

The standard pharmacist intervention involving medication review, patient interview, and recommendations to the physician is in accordance with previously described literature [44, 45]. However, some studies also included additional responsibilities in the intervention including new medicine prescription, laboratory assessments or deprescribing which is also consistent with existing literature [44, 46]. The additional responsibilities identified in our review should be compared with the roles assigned to community pharmacists in different countries. Notably, the implementation of legislation supporting pharmacist prescribing in the United Kingdom, Canada, the United States, and New Zealand may explain the emergence of these new responsibilities highlighted in our review [47, 48]. In this collaboration, physicians were also core members. Previous authors have analyzed pharmacist-physician collaboration [45, 49, 50], either to determine factors influencing collaboration [51] or to explore attitudes towards interprofessional collaboration [52]. Only five studies involved other health professionals, which was less than expected.

Because of the limited number of studies incorporating more than two professionals, we were unable to investigate the correlation between the number of professions in a collaboration and its impact on patient health and satisfaction outcomes. However, this variable was explored in a recent systematic review which found no association between the number of professions in the interprofessional collaboration and HbA1c reduction [53].

A large majority of included articles evaluated the role of a pharmacist intervention in managing cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, particularly blood pressure. This supports evidence from recent reviews [44, 53, 54]. Indeed, the meta-analysis of Tan et al. (2014), including four studies that were also included in our review [29, 30, 34, 37], reported that interventions involving pharmacists or nurses were associated with significantly improved BP control [44]. Moreover, some included studies reported that pharmacist care improved lipid parameters, notably LDL-C levels, as well as increasing the proportion of patients who achieved targeted levels which is consistent with existing literature [55]. In contrast, results concerning HbA1c were conflicting. Whilst we found only one study reporting positive effects, previous research reported more studies with positive effects on HbA1c with pharmacist interventions [44, 56, 57]. Tan et al. (2014) found four studies with positive effects and two studies with no effect and concluded with a meta-analysis that HbA1c reduced by 0.88% in the intervention group [44]. In Pousinho et al. (2016) review, HbA1c was considered as an outcome measure in 26 studies and 24 studies reported a greater improvement in this outcome in the intervention group compared with the control group [56]. The divergence in results could be explained by the fact that in our included studies, the pharmacist interventions were not directly focused on diabetes but were a secondary outcome measure.

Concerning quality of life and patient satisfaction, our review did not report significant results. Many different assessment tools were used to explore these two variables which may explain these results. Similarly, an umbrella review conducted by Abdulrhim et al. (2020) was unable to conclude about improvements in quality of life for patients with diabetes due to the use of diverse quality of life assessment tools [57].

Bias of included studies

Only randomized controlled trials were included in this systematic review because they provide the most reliable evidence on intervention effectiveness. However, the quality assessment revealed that the majority of the included studies had a moderate risk of bias mainly due to their methodological quality. No article had a methodology with double blinding, which is a strong criterion in quality assessment. This absence was anticipated, considering the nature of the interventions, where professionals involvement precludes blinding. Therefore, the certainty of evidence supporting the conclusions about intervention effectiveness is low.

Limitations

Despite following PRISMA guidelines, our systematic review did have some limitations. Firstly, the exclusive focus on RCTs improves the robustness of the review. However, there is limited availability of relevant RCTs for significant primary care topics, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [58], or infection [59], which were consequently omitted from our synthesis. Secondly, even though we chose to only include RCTs, it was still difficult to group the outcomes to assess the effect of pharmacist involvement in a primary care interprofessional team. A number of factors explain this, including the differences in patient populations, follow-up durations, instruments used to measure outcome and intervention complexity. These discrepancies deserve further thought and investigation into appropriate core outcome measure to be used in primary care research and strategies and methods currently used to optimize implementation of complex interventions [60, 61]. Thirdly, the quality assessment revealed that the majority of included studies had a moderate risk of bias due to their methodological quality. Finally, there is no existing consensus defining interprofessional collaboration [62, 63] and the search strategy had to consider several terms. We used Mesh terms in the search strategy to be more specific. Moreover, to our knowledge, there are no recommendations about professions which should be involved in a primary care interprofessional team, and this made it difficult to select studies.

Conclusion

This review revealed that pharmacists are mainly responsible for medication review, interview with patients and recommendations to physicians, and most commonly collaborate with physicians. Pharmacist collaboration particularly improved blood pressure and cholesterol control. Our review highlights the need for further controlled studies into interprofessional collaboration interventions involving a pharmacist in primary care across the full range of medical conditions.

Data availability

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article and its supplementary materials.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Index Mass

- BP:

-

blood pressure

- DBP:

-

diastolic blood pressure

- HbA1c:

-

glycosylated hemoglobin

- HDL-C:

-

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C:

-

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- RCT:

-

randomized controlled trials

- SBP:

-

systolic blood pressure

References

Gilbert JH, Yan J, Hoffman SJ. A WHO report: framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. J Allied Health. 2010 Fall;39 Suppl 1:196-7. PMID: 21174039.

Jiao F, Fung CSC, Wan YF, McGhee SM, Wong CKH, Dai D, et al. Long-term effects of the multidisciplinary risk assessment and management program for patients with diabetes mellitus (RAMP-DM): a population-based cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2015;14(1):105.

Matzke GR, Moczygemba LR, Williams KJ, Czar MJ, Lee WT. Impact of a pharmacist-physician collaborative care model on patient outcomes and health services utilization. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(14):1039–47.

Veet CA, Radomski TR, D’Avella C, Hernandez I, Wessel C, Swart ECS, et al. Impact of healthcare delivery system type on clinical, utilization, and cost outcomes of patient-centered medical homes: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(4):1276–84.

Körner M, Bütof S, Müller C, Zimmermann L, Becker S, Bengel J. Interprofessional teamwork and team interventions in chronic care: a systematic review. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(1):15–28.

Song H, Ryan M, Tendulkar S, Fisher J, Martin J, Peters AS, et al. Team dynamics, clinical work satisfaction, and patient care coordination between primary care providers: a mixed methods study. Health Care Manage Rev. 2017;42(1):28–41.

Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573–6.

Haldane V, De Foo C, Abdalla SM, Jung AS, Tan M, Wu S, et al. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from 28 countries. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):964–80.

Davis B, Bankhead-Kendall BK, Dumas RP. A review of COVID-19’s impact on modern medical systems from a health organization management perspective. Health Technol (Berl). 2022;12(4):815–24.

Jordan D, Guiu-Segura JM, Sousa-Pinto G, Wang LN. How COVID-19 has impacted the role of pharmacists around the world. Farm Hosp. 2021;45(2):89–95.

Costa S, Romão M, Mendes M, Horta MR, Rodrigues AT, Carneiro AV, et al. Pharmacy interventions on COVID-19 in Europe: Mapping current practices and a scoping review. Res Social Administrative Pharm. 2022;18(8):3338–49.

Crawford ND, Myers S, Young H, Klepser D, Tung E. The role of pharmacies in the HIV Prevention and Care continuums: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(6):1819.

Banh HL, Chow S, Li S, Letassy N, Cox C, Cave A. Pharmacy students screening for pre-diabetes/diabetes with a validated questionnaire in community pharmacies during their experiential rotation in Alberta, Canada. SAGE Open Med. 2015;3:2050312115585040.

Holle LM, Levine J, Buckley T, White CM, White C, Hadfield MJ. Pharmacist intervention in colorectal cancer screening initiative. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2020;60(4):e109–16.

Mir JF, Estrada-Campmany M, Heredia A, Rodríguez-Caba C, Alcalde M, Espinosa N, et al. Role of community pharmacists in skin cancer screening: a descriptive study of skin cancer risk factors prevalence and photoprotection habits in Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2019;17(3):1455.

Lewis J, Barry AR, Bellefeuille K, Pammett RT. Perceptions of Independent Pharmacist Prescribing among Health Authority- and community-based pharmacists in Northern British Columbia. Pharm (Basel). 2021;9(2):92.

Bužančić I, Kummer I, Držaić M, Ortner Hadžiabdić M. Community-based pharmacists’ role in deprescribing: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(2):452–63.

Wu JHC, Khalid F, Langford BJ, Beahm NP, McIntyre M, Schwartz KL, et al. Community pharmacist prescribing of antimicrobials: a systematic review from an antimicrobial stewardship perspective. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2021;154(3):179–92.

Luchen GG, Prohaska ES, Ruisinger JF, Melton BL. Impact of community pharmacist intervention on concurrent benzodiazepine and opioid prescribing patterns. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2019;59(2):238–42.

Pascucci D, Sassano M, Nurchis MC, Cicconi M, Acampora A, Park D, et al. Impact of interprofessional collaboration on chronic disease management: findings from a systematic review of clinical trial and meta-analysis. Health Policy. 2021;125(2):191–202.

Wei H, Horns P, Sears SF, Huang K, Smith CM, Wei TL. A systematic meta-review of systematic reviews about interprofessional collaboration: facilitators, barriers, and outcomes. J Interprof Care. 2022;36(5):735–49.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ [Internet]. 2015 Jan 2 [cited 2020 Apr 13];349. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g7647.

Bouton C, Journeaux M, Jourdain M, Angibaud M, Huon JF, Rat C. Interprofessional collaboration in primary care: what effect on patient health? A systematic literature review. BMC Prim Care. 2023;24(1):253.

Zingg W, Castro-Sanchez E, Secci FV, Edwards R, Drumright LN, Sevdalis N, et al. Innovative tools for quality assessment: integrated quality criteria for review of multiple study designs (ICROMS). Public Health. 2016;133:19–37.

Carter BL, Ardery G, Dawson JD, James PA, Bergus GR, Doucette WR, et al. Physician and pharmacist collaboration to improve blood pressure control. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1996–2002.

Carter BL, Coffey CS, Ardery G, Uribe L, Ecklund D, James P, et al. Cluster-randomized trial of a physician/pharmacist collaborative model to improve blood pressure control. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(3):235–43.

Carter BL, Levy B, Gryzlak B, Xu Y, Chrischilles E, Dawson J, et al. Cluster-randomized trial to evaluate a centralized clinical Pharmacy Service in Private Family Medicine offices. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(6):e004188.

Chen Z, Ernst ME, Ardery G, Xu Y, Carter BL. Physician-pharmacist co-management and 24-hour blood pressure control. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2013;15(5):337–43.

Heisler M, Hofer TP, Schmittdiel JA, Selby JV, Klamerus ML, Bosworth HB, et al. Improving blood pressure control through a clinical pharmacist outreach program in patients with diabetes mellitus in 2 high-performing health systems: the adherence and intensification of medications cluster randomized, controlled pragmatic trial. Circulation. 2012;125(23):2863–72.

Hogg W, Lemelin J, Dahrouge S, Liddy C, Armstrong CD, Legault F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of anticipatory and preventive multidisciplinary team care: for complex patients in a community-based primary care setting. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(12):e76–85.

Jameson JP, Baty PJ. Pharmacist collaborative management of poorly controlled diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(4):250–5.

Omran D, Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, Tsuyuki RT, Lewanczuk RZ, Guirguis LM et al. Pharmacists on primary care teams: Effect on antihypertensive medication management in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2015;55(3):265–8.

Pape GA, Hunt JS, Butler KL, Siemienczuk J, LeBlanc BH, Gillanders W, et al. Team-based care approach to cholesterol management in diabetes mellitus: two-year cluster randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(16):1480–6.

Simpson SH, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Lewanczuk RZ, Spooner R, Johnson JA. Effect of adding pharmacists to primary care teams on blood pressure control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):20–6.

Smith SM, Carris NW, Dietrich E, Gums JG, Uribe L, Coffey CS, et al. Physician-pharmacist collaboration versus usual care for treatment-resistant hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2016;10(4):307–17.

Tahaineh L, Albsoul-Younes A, Al-Ashqar E, Habeb A. The role of clinical pharmacist on lipid control in dyslipidemic patients in North of Jordan. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(2):229–36.

Tobari H, Arimoto T, Shimojo N, Yuhara K, Noda H, Yamagishi K, et al. Physician-pharmacist cooperation program for blood pressure control in patients with hypertension: a randomized-controlled trial. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23(10):1144–52.

Weber CA, Ernst ME, Sezate GS, Zheng S, Carter BL. Pharmacist-physician comanagement of hypertension and reduction in 24-hour ambulatory blood pressures. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1634–9.

Finley PR, Rens HR, Pont JT, Gess SL, Louie C, Bull SA, et al. Impact of a collaborative pharmacy practice model on the treatment of depression in primary care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(16):1518–26.

Finley PR, Rens HR, Pont JT, Gess SL, Louie C, Bull SA, et al. Impact of a collaborative care model on depression in a primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(9):1175–85.

Lenaghan E, Holland R, Brooks A. Home-based medication review in a high risk elderly population in primary care - the POLYMED randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2007;36(3):292–7.

Adler DA, Bungay KM, Wilson IB, Pei Y, Supran S, Peckham E, et al. The impact of a pharmacist intervention on 6-month outcomes in depressed primary care patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26(3):199–209.

Sellors J, Kaczorowski J, Sellors C, Dolovich L, Woodward C, Willan A, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a pharmacist consultation program for family physicians and their elderly patients. CMAJ. 2003;169(1):17–22.

Tan ECK, Stewart K, Elliott RA, George J. Pharmacist services provided in general practice clinics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2014;10(4):608–22.

Hwang AY, Gums TH, Gums JG. The benefits of physician-pharmacist collaboration. J Fam Pract. 2017;66(12):E1–8.

Famiyeh IM, MacKeigan L, Thompson A, Kuluski K, McCarthy LM. Exploring pharmacy service users’ support for and willingness to use community pharmacist prescribing services. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;15(5):575–83.

Zhou M, Desborough J, Parkinson A, Douglas K, McDonald D, Boom K. Barriers to pharmacist prescribing: a scoping review comparing the UK, New Zealand, Canadian and Australian experiences. Int J Pharm Pract. 2019;27(6):479–89.

Riordan DO, Walsh KA, Galvin R, Sinnott C, Kearney PM, Byrne S. The effect of pharmacist-led interventions in optimising prescribing in older adults in primary care: a systematic review. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4:2050312116652568.

Farland MZ, Byrd DC, McFarland MS, Thomas J, Franks AS, George CM, et al. Pharmacist-physician collaboration for diabetes care: the diabetes initiative program. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(6):781–9.

McKinnon A, Jorgenson D. Pharmacist and physician collaborative prescribing: for medication renewals within a primary health centre. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(12):e86–91.

Bollen A, Harrison R, Aslani P, van Haastregt JCM. Factors influencing interprofessional collaboration between community pharmacists and general practitioners - a systematic review. Health Soc Care Commun. 2019;27(4):e189–212.

Löffler C, Koudmani C, Böhmer F, Paschka SD, Höck J, Drewelow E, et al. Perceptions of interprofessional collaboration of general practitioners and community pharmacists - a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):224.

Lee JK, McCutcheon LRM, Fazel MT, Cooley JH, Slack MK. Assessment of Interprofessional Collaborative Practices and outcomes in adults with diabetes and hypertension in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2036725.

Yuan C, Ding Y, Zhou K, Huang Y, Xi X. Clinical outcomes of community pharmacy services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Soc Care Commun. 2019;27(5):e567–87.

Charrois TL, Zolezzi M, Koshman SL, Pearson G, Makowsky M, Durec T, et al. A systematic review of the evidence for pharmacist care of patients with dyslipidemia. Pharmacotherapy: J Hum Pharmacol Drug Therapy. 2012;32(3):222–33.

Pousinho S, Morgado M, Falcão A, Alves G. Pharmacist interventions in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. JMCP. 2016;22(5):493–515.

Abdulrhim S, Sankaralingam S, Ibrahim MIM, Awaisu A. The impact of pharmacist care on diabetes outcomes in primary care settings: an umbrella review of published systematic reviews. Prim Care Diabetes. 2020;14(5):393–400.

Kimball BK, Tutalo RA, Minami T, Eaton CB. Evaluating an integrated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management program implemented in a primary care setting. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2021;4(6):697–710.

Swart A, Benrimoj SI, Dineen-Griffin S. The clinical and economic evidence of the management of urinary tract infections by community pharmacists in women aged 16 to 65 years: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pharm. 2024.

Levati S, Campbell P, Frost R, Dougall N, Wells M, Donaldson C, et al. Optimisation of complex health interventions prior to a randomised controlled trial: a scoping review of strategies used. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2016;2(1):17.

Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Bayliss E, Nothelle S, Senn N, Shadmi E. Challenges and Next steps for Primary Care Research. Annals Family Med. 2018;16(1):85–6.

Mahler C, Gutmann T, Karstens S, Joos S. Terminology for interprofessional collaboration: definition and current practice. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2014;31(4):Doc40.

Chamberlain-Salaun J, Mills J, Usher K. Terminology used to describe health care teams: an integrative review of the literature. JMDH. 2013;6:65–74.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the staff of the Bibliothèque Universitaire Santé, Université de Nantes for their help in developing the search strategy and Colin Sidre (Bibliothèque inter-universitaire Santé médecine, Université Paris Cité) for his help in data extraction from the CINAHL database.

This article received financial support for critical revision and editing from the French network of University Hospitals HUGO (‘Hôpitaux Universitaires du Grand Ouest’), and the critical revision and editing were performed by Amy Whereat of Speak the Speech Consulting.

Funding

The authors declare this research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to study design. SG, LR, AN and AM assessed studies for inclusion and participated in data extraction. MA, JFH and MJ contributed to data analysis. MA and JFH did the critical appraisal of the studies. MA contributed to writing, and JFH and CR contributed to revising of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Angibaud, M., Jourdain, M., Girard, S. et al. Involving community pharmacists in interprofessional collaboration in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Prim. Care 25, 103 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02326-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02326-3