Abstract

Background

Because of the adverse effects of morphine and its derivatives, non-opioid analgesia procedures are proposed after outpatient surgery. Without opioids, the ability to provide quality analgesia after the patient returns home may be questioned. We examined whether an opioid-free strategy could ensure satisfactory analgesia after ambulatory laparoscopic colectomy.

Methods

We performed a retrospective observational single-center study (of prospective collected database) including all patients eligible for scheduled outpatient colectomy. Postoperative analgesia was provided by paracetamol and nefopam. Postoperative follow-up included pain at mobilization (assessed by a numerical rating scale, NRS), hemodynamic variables, temperature, resumption of transit and biological markers of postoperative inflammation. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients with moderate to severe pain (NRS > 4) the day after surgery.

Results

Data from 144 patients were analyzed. The majority were men aged 59 ± 12 years with a mean BMI of 27 [25-30] kg/m2. ASA scores were 1 for 14%, 2 for 59% and 3 for 27% of patients. Forty-seven patients (33%) underwent surgery for cancer, 94 for sigmoiditis (65%) and 3 (2%) for another colonic pathology. Postoperative pain was affected by time since surgery (Q3 = 52.4,p < 0.001) and decreased significantly from day to day. The incidence of moderate to severe pain at mobilization (NRS > 4) on the first day after surgery was (0.19; 95% CI, 0.13–0.27).

Conclusion

Non-opioid analgesia after ambulatory laparoscopic colectomy seems efficient to ensure adequate analgesia. This therapeutic strategy makes it possible to avoid the adverse effects of opioids.

Trial registration

The study was retrospectively registered and approved by the relevant institutional review board (CERAR) reference IRB 00010254–2018 – 188). All patients gave written informed consent for analysis of their data. The anonymous database was declared to the French Data Protection Authority (CNIL) (reference 221 2976 v0 of April 12, 2019).

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

For several years, health regulatory authorities have multiplied incentives to develop outpatient surgery. This reduces infectious and thromboembolic risks and social morbidity, and allows faster functional recovery [1, 2]. Outpatient care has become essential for increasingly varied and major procedures [3]. Its development has been encouraged by enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) techniques, minimally invasive surgical techniques and above all by the optimization of peri-anesthetic management, particularly postoperative analgesia. The latter frequently involves opioids [4]. Because of concern about the undesirable effects of morphine and its derivatives [5], non-opioid analgesia after discharge has been considered. This strategy has value in resumption of transit after colonic surgery [6] and avoids the risk of morphine addiction [7]. However, the absence of opioids postoperatively has raised concerns that quality analgesia may not be possible after patients return home.

The main objective of this observational study was to describe the effect of a postoperative analgesic protocol without opioids after laparoscopic outpatient colectomy.

Methods

Ethics

This retrospective observational single-center study was conducted from December 4, 2014, to November 5, 2020 in the Hopital Privé de l’Estuaire (Le Havre, France). It was approved by the relevant institutional review board (Comité d’Ethique pour la Recherche en Anesthésie Réanimation [CERAR] reference IRB 00010254–2018 – 188). All patients gave written informed consent for analysis of their data. The anonymous database was declared to the French Data Protection Authority (CNIL) (reference 221 2976 v0 of April 12, 2019). This report follows the STROBE recommendations [9].

Study population

All patients requiring scheduled outpatient colectomy for a cancerous lesion or a single degenerating polyp with left, right or high rectal (above the pouch of Douglas) colonic location or diverticular pathology with multiple episodes of acute sigmoiditis were included consecutively. Patients who were not eligible for a laparoscopic procedure were excluded from ambulatory care and from the present study. These were patients who had already undergone multiple surgeries, who were receiving anticoagulant treatment, insulin-dependent diabetic patients, patients who refused or did not understand the ambulatory care pathway, socially and emotionally isolated patients, minors, pregnant women and patients in custody.

Perioperative care

Anesthetic and surgical diagnostic and therapeutic management was not modified for the purpose of this study. It was consistent with the management of patients operated on as outpatients prior to this study and with the state of the art [2].

Ambulatory care was proposed during the surgery consultation and validated during the anesthesia consultation. The steps of the care pathway were explained orally and by means of an information booklet. The patients’ attention was drawn to the known benefits of outpatient care, the need to take 400 ml isotonic sugar solution 2 h before the procedure, and the need for systematic adherence for the postoperative analgesic prescription. They were given a contact number for help and assistance after returning home, particularly in the event of uncontrolled pain. Postoperative analgesics (paracetamol 15 mg/kg every 6 h and nefopam 40 mg 4 times a day on a sugar cube) and thromboembolic prophylaxis (subcutaneous enoxaparin 4000 IU once a day) were prescribed during these consultations. The surgical assistant then again fully explained the care pathway and was also in charge of organizing and coordinating the nursing follow-up.

No anxiolytic premedication was given. The anesthesia and surgery protocol was the same for all patients (Table 1) and was based on French [10] and international [2] recommendations. All procedures were performed laparoscopically. No colonic preparation was performed and no drains of the abdominal cavity or urinary catheters were left in place. No patient had a gastric tube inserted. Anesthesia induction and maintenance were achieved by Total Intravenous Anesthesia (TIVA) using remifentanil and propofol. The intraoperative analgesia consisted both by intravenous analgesia (paracetamol and nefopam just after the anesthetic induction associated to dexamethasone 0.2 mg.kg− 1 and Ketamine) and local anesthetics administration by bilateral TAP block (30 to 40 ml of ropivacaine 5 mg/ml). At the skin closure, a morphine bolus (0.15 mg.kg− 1) was given). There was nor infiltration of trocar sites nor intravenous lidocaine.

Patients were encouraged to chew gum as soon as they were able to cooperate adequately in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU). When the Aldrete score was > 9, allowing patients to return to their rooms [11], they were cared for by the outpatient department nurse according to a pre-established protocol (Table 1). After a Post Anesthetic Discharge Scoring System (PADSS) score > 9 was achieved [12], discharge was validated by the surgeon and the anesthesiologist at the same time after checking the stability of the hemoglobin level (postoperative control value compared with preoperative value with acceptance of a variation < 1 g/dl or 10% of the initial value). The patient and their relatives were reminded of the instructions given preoperatively.

As soon as the patient returned home, postoperative supervision was ensured by a visiting home nurse on the evening of the procedure, twice daily from postoperative day 1 (POD 1) to POD 5 and then daily from POD 6 to POD 10. The surgical assistant contacted the patients daily by telephone until they were seen again by the surgeon. Blood samples were taken at home at POD 1, POD 3 and POD 5 for blood count and serum C-reactive protein (CRP) measurement. All patients were seen by the surgeon during a scheduled consultation around POD 10 and again at POD 21.

Collected variables

The intensity of postoperative pain at mobilization was self-assessed using a numerical rating scale (NRS) at discharge from the ambulatory care unit, twice daily from POD 1 to POD 5 and then daily during the nurse’s home visit. From POD 1 to POD 5, the average of the two NRS values was retained. Medical data (heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, nausea or vomiting, time of first drink, getting up, meals, discharge from the PACU and from hospital, flatus, resumption of transit) as well as medication administration or intake were collected from the medical record.

Statistical analysis

Outcome criteria

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients with mobilization pain intensity NRS > 4 on the first postoperative day (POD 1).

Data

Categorical variables are presented as percentages (95% confidence interval). Continuous variables are presented as mean (SD) or median [interquartile] depending on the normality of the distribution.

The effect of time on continuous variables was evaluated using a Friedman test followed by a post-hoc Dunn test using PRISM 5 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif.). The difference was considered statistically significant when the risk of first-order error was < 5%.

Missing data were replaced by the median of distribution for calculation of the Friedman test and the post-hoc Dunn test.

Results

Study population

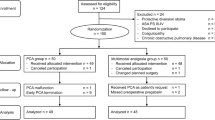

A pilot study including the first 15 patients was conducted from December 4, 2014, to April 16, 2016. Recruitment continued until November 5, 2020. During the study period, 359 colectomies were performed including 65 emergency procedures. Of the 294 patients who had scheduled surgery, 197 (67%) were eligible for outpatient colectomy but 6 (3% of eligible patients) refused this care pathway. A total of 191 patients entered the outpatient procedure but only 176 patients were included in the present study because the pilot study patients were excluded from analysis. Four of these patients refused use of their data and 2 could not be contacted. Ten patients were not discharged on the day of surgery due to disabling postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) (n = 2), residual sedation (n = 1), acute gastric pain (n = 1), absence of a caregiver (n = 1), last-minute refusal of discharge by the family (n = 1), intraoperative spleen injury (n = 1) and conversion to laparotomy (n = 3). Except for one of these 10 patients who was hospitalized for 8 days, the other 9 patients were discharged the day after surgery.

A total of 160 patients underwent colectomy and were discharged the same day. Main outcome data (postoperative pain assessed by NRS) were missing in 16 patients. Final statistical analysis was conducted in 144 patients. The flow chart is shown in Fig. 1.

Patients were aged 59 ± 12 years and 80 (56%) were male. Their mean body mass index (BMI) was 27 [25-30] kg/m2. ASA score was 1 in 14% of patients, 2 in 59% and 3 in 27%. Smoking (17%), hypertension (38%), type II diabetes (12%) and dyslipidemia (27%) were common. Forty-seven patients (33%) had surgery for cancer, 94 for sigmoiditis (65%) and 3 (2%) for another colonic pathology. Mean duration of surgery was 95 [78–110] min. Mean duration of stay in the PACU was 83 [70–101] min. Only one patient required additional morphine titration during this time. No patient had PONV in the PACU.

Patients drank fluids 5 [2-35] min after arrival in the outpatient surgery department. They woke after 46 [45–60] min to take a chairside meal 52 [45–65] min after arrival. Only 2 patients experienced nausea. Most patients (92%) received oral analgesics (paracetamol, nefopam or both). Eleven patients refused additional analgesics after discharge from the PACU. None required morphine. After surgery, patients spent 7 h 13 min [6 h 23 min − 7 h 57 min] in the hospital before discharge.

Postoperative pain and main outcome criteria

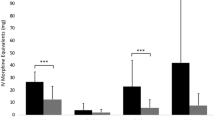

Postoperative pain was affected by time since surgery (Q3 = 52.4, P < 0.001) and decreased significantly from day to day (Fig. 2).

The incidence of moderate to severe pain (NRS > 4) at POD 1 was (0.19; 95% CI 0.13 to 0.27).

Postoperative events

All patients operated during the study period had the same follow-up. For the 144 patients included in final analysis, postoperative home monitoring showed 126 patients (87.5%) first passed flatus at POD 1 and 127 (88%) first passed stool between POD 1 and POD 2.

In accordance with the established monitoring protocol, 14 patients had an unscheduled surgical consultation before POD 10. No patient needed medical assistance to return to the hospital. Ten patients returned home after clinical examination, 6 of these with a reminder of analgesia instructions and 4 with a home nursing prescription for parietal infection or hematoma. Four patients were rehospitalized: one for secondary ileus at POD 2, one for low oxygen saturation at POD 2. This patient was morbidly obese (BMI 43) and subsequently had active pulmonary physiotherapy. Both these patients were discharged before POD 5 and follow-up was uneventful. Two patients required surgery for anastomotic fistula, one of whom experienced severe septic shock and was admitted to intensive care (Clavien-Dindo grade IIIb). No patient died. Blood pressure, heart rate and temperature remained within physiological limits during the first 5 postoperative days (Table 2). Laboratory tests showed an inflammatory syndrome that progressively decreased (Table 2).

The other patients not included in final analysis (patients who were not discharged on the same day or who had missing data) had identical follow-up. Thirteen patients had an unscheduled surgical consultation before POD 10. Six patients returned home after clinical examination, 3 of these with a reminder of analgesia instructions and 3 with a home nursing prescription for parietal infection or hematoma. Seven patients were rehospitalized: one for secondary ileus at POD 2 which resolved spontaneously before POD 4, one with tachycardia revealing arrhythmia and who was transferred to the cardiology unit, one for PONV at POD 1 but who was discharged at POD 2, and one with a history of throat cancer who developed inhalation pneumopathy. Three patients underwent further surgery: one for eventration at POD 1, one at POD 10 for necrosis of the epiploon and one for anastomotic fistula at POD 3. Follow-up was uneventful. No patient died.

Discussion

Our study describes the evolution of pain intensity in the immediate postoperative period after ambulatory laparoscopic colectomy. We found that postoperative analgesic management without morphine provided satisfactory pain control, not different during the first 2 days to that reported after opioid use in most studies [4, 13].

Outpatient surgery is developing in response to joint demand from medical scientific societies and health regulatory authorities. It seems difficult to extend ambulatory care if postoperative pain control cannot be ensured. Recent studies show that pain, together with PONV [14], is at the forefront of postoperative complaints and is the main reason for patients’ calls during the first week after surgery [15]. Pain relief is considered a fundamental right by some authors [16] and justifies optimal care. But it has been questioned [17] whether achieving postoperative pain close to 0 is realistic when this involves widespread use of opioids [4], whose dangerousness is now proven by the addiction epidemic in the USA [18, 19]. The American directive published in 2000 by the Joint Commission of Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations made pain assessment mandatory, but led to a wider use of opioids, with their associated side-effects [20]. However, patient satisfaction is not related to pain management alone, since less than 4% of outpatients would have preferred hospitalization although 30% reported moderate or severe pain [21, 22].

Most studies relate to interventions classically performed on an outpatient basis (arthroscopy, hallux valgus, cholecystectomy, gynecological or parietal surgery). Unlike our series, they do not concern major abdominal surgery. We demonstrate that opioid-free analgesia yielded satisfactory results in patients discharged home after outpatient colectomy. At POD 1, 19% (28 of 144 patients) had an NRS score > 4, which is identical to or lower than that reported in the literature for less serious procedures [14, 23, 24]. In an older Canadian study, 30% of patients had an NRS > 4 the day after ambulatory surgery [24]. In a more recent, smaller study, 68% of patients had an NRS > 4 at POD 1 [25]. At POD 3, 75% of our patients had an NRS ≤ 3. The NRS score and all vital signs and variables were followed until POD 10.

Our study is the first that focuses specifically on the quality of opioid-free postoperative analgesia in outpatient surgery for a major procedure such as colectomy. Of note, it is not based on an assessment of pain at rest. Indeed, patients are not laying in a hospital bed but live their lives at home. The NRS was assessed twice daily until POD 5 and continued daily until POD 10. Such evaluation reduced the risk of undetected uncontrolled pain. Patients could also call a dedicated number at any time for any pre- and postoperative questions.

Post-colectomy pain has so far only been assessed for hospitalized cases [4, 25]. Gerbershagen et al., evaluating pain at POD 1 for 170 surgical procedures, found a mean NRS after sigmoidectomy of 5 (range, 4–7) [25]. Although the procedure was performed by open surgery and not by laparoscopy, patients had epidural analgesia or received an average of 18 mg intravenous morphine. Grass et al. assessed pain scores and daily analgesics consumption until 96 h postoperatively after colectomies, comparing laparoscopic and open surgeries [4]. The analgesic strategy included epidural for open surgery and various painkillers for laparoscopic approach but always with postoperative opioids.

In our study, all the patients underwent laparoscopic surgery and the intra and postoperative analgesic strategy was identical for all patients. Although we excluded opioid prescriptions from our postoperative protocol, the pain relief obtained at POD 1 with oral administration of 2 opioid-free analgesics was therefore satisfactory. The first-line prescription did not include a third analgesic as we considered that pain could be a warning sign of surgical complications. Also, the chosen analgesics (paracetamol, nefopam) have shown their effectiveness [26] and synergistic action [27] with few side-effects that could delay resumption of transit. The effectiveness of multimodal analgesia has been demonstrated [28] with a dose-effect curve related to the number of drugs used [29]. This combination of analgesics avoids the complications and side-effects of morphine [30]. It follows ERAS recommendations that encourage morphine saving and the PROSPECT group guidelines [31]. In the event of uncontrolled pain, we first checked compliance with the analgesic treatment before considering an unscheduled consultation. The quality of analgesia in our study is explained above all by the intraoperative measures that aimed to reduce pain. Postoperative pain is a complex phenomenon [32] but central sensitization and the inflammatory component explain why pain persists long after the end of the surgical procedure. Our perioperative management aimed above all to reduce the intensity of pain. The first measure was the exclusive laparoscopic approach. Laparoscopy has been shown to greatly reduce the inflammatory response compared with open surgery [33]. We also prevented pain [34, 35] by initiating multimodal analgesia upon anesthetic induction with ketamine for NMDA receptor blockade, dexamethasone administration at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg [36] and regional anesthesia by bilateral TAP block whose value and low morbidity have previously been described [37,38,39]. As the patients were called each day, they were reminded of their medication instructions (based on a regular intake) but we did not collect specific data on the analgesics intake.

An important finding of this study was the wide acceptance by patients of ambulatory management for colectomy. Implementation of the ERAS program since 2011 by the surgeon involved in this study had reduced length of stay for left colectomies to 48 h. Careful explanation of both the safety of the outpatient care pathway and postoperative pain management helped gain the support and confidence of most patients; only 6 refused the proposed treatment. Moreover, outpatient care is of great value for elderly patients by avoiding hospitalization that leads to loss of bearings and increased risk of institutionalization [40].

Our study has some limitations. It was an observational retrospective study even if all the data were prospectively collected. A randomized study (with or without postoperative opioids) was not an option because it would have run counter to the ERAS recommendations for postoperative analgesia. Another limitation is the small patient population and the fact that it was a single-center, single-operator study. It is therefore difficult to judge the reproducibility of our results. As the operation time is recognized as an independent risk factor increasing postoperative pain peaks [4], the surgical duration associated to our study surgeon could be a confounding factor. Grass et al. have also shown that duration of surgery less than 180 min is an independent factor favouring a short hospital stay [41]. The home nurse concept could be difficult to implement even if all patients need postoperative thrombotic prophylaxis so nurses at home each day for up to 4 weeks. But home nurses collect data used in an algorithm designed for patient safety and early complications detection. This data collection can be done by digital application.

Even if this study was conducted on a long period (6 years), the perioperative anesthetic and surgical management remained strictly the same, based on the Evidence Based Medicine (ERAS recommendations).

Conclusion

Home analgesia without opioids after ambulatory laparoscopic colectomy seems efficient to ensure pain relief. Such a therapeutic strategy avoids the adverse effects of opioids regarding both resumption of transit and risk of misuse. This high-quality management allows patients to benefit from all the advantages of the ambulatory care pathway without fear of inadequate pain relief.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ERAS:

-

enhanced recovery after surgery

- NMDA blockade:

-

N-methyl-D-aspartate blockade

- PEEP:

-

positive end expiratory pressure

- POD:

-

postoperative day

- PONV:

-

postoperative nausea and vomiting

- TAP block:

-

transverse abdominal plane block

- NRS:

-

Numerical Pain Rating Scale

References

Gignoux B, Pasquer A, Vulliez A, Lanz T. Outpatient colectomy within an enhanced recovery program. J Visc Surg. 2015;152:11–5.

Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, Nygren J, Demartines N, Francis N, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colonic surgery: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations 2018. World J Surg. 2019;43(3):659–95.

Badaoui R, Alami Chentoufi Y, Hchikat A, Rebibo L, Popov I, Dhahri A, et al. Outpatient laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: first 100 cases. J Clin Anesth. 2016;34:85–90.

Grass F, Cachemaille M, Martin D, Fournier N, Hahnloser D, et al. Pain perception after colorectal surgery: a propensity score matched prospective cohort study. Biosci Trends. 2018;12:47–53.

Colvin LA, Bull F, Hales TG. Perioperative opioid analgesia-when is enough too much? A review of opioid-induced tolerance and hyperalgesia. Lancet. 2019;393:1558–68.

Drewes AM, Munkholm P, Simrén M, Breivik H, Kongsgaard UE, Hatlebakk JG, et al. Of the nordic Working Group. Scand J Pain. 2016;11:111–22.

Hah JM, Bateman BT, Ratliff J, Curtin C, Sun E. Chronic opioid use after surgery: implications for perioperative management in the face of the opioid epidemic. Anesth Analg. 2017;125:1733–40.

Gramke HF, de Rijke JM, van Kleef M, Kessels AG, Peters ML, Sommer M, et al. Predictive factors of postoperative pain after day-case surgery. Clin J Pain. 2009;25:455–60.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, STROBE Initiative Collaborators. The strengthening the reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9.

Alfonsi P, Slim K, Chauvin M, Mariani P, Faucheron JL, Fletcher D. Le Groupe De travail de la Société française d’anesthésie et réanimation (Sfar) et de la Société française de chirurgie digestive. [Guidelines for enhanced recovery after elective colorectal surgery]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2014;33(5):370–84.

Aldrete JA. The post-anesthesia recovery score revisited. J Clin Anesth. 1995;7:89–91.

Chung F. Discharge criteria–a new trend. Can J Anesth. 1995;42:1056–8.

Chung F, Ritchie E, Su J. Postoperative pain in ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 1997;85:808–16.

Bruderer U, Fisler A, Steurer MP, Steurer M, Dullenkopf A. Post-discharge nausea and vomiting after total intravenous anaesthesia and standardised PONV prophylaxis for ambulatory surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2017;61:758–66.

Brix LD, Bjørnholdt KT, Thillemann TM, Nikolajsen L. Pain-related unscheduled contact with healthcare services after outpatient surgery. Anaesthesia. 2017;72:870–8.

Brennan F, Carr DB, Cousins M. Pain management: a fundamental human right. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:205–21.

McAlister VC. Tyranny of the pain score question after surgery. Can J Surg. 2018;61:364–5.

Yaster M, Benzon HT, Anderson TA. Houston, we have a problem! The role of the anesthesiologist in the current opioid epidemic. Anesth Analg. 2017;125:1429–31.

Skolnick P. The opioid epidemic: Crisis and solutions. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018;58:143–59.

Levy N, Sturgess J, Mills P. Pain as the fifth vital sign and dependence on the numerical pain scale is being abandoned in the US: why ? Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:435–8.

Burch T, Seipel SJ, Coyle N, Ortega KH, DeJesus O. Postoperative visual analog pain scores and overall anesthesia patient satisfaction. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2017;29:419–26.

Beauregard L, Pomp A, Choinière M. Severity and impact of pain after day-surgery. Can J Anesth. 1998;45:304–11.

McGrath B, Elgendy H, Chung F, Kamming D, Curti B, King S. 30% of patients have moderate to severe pain 24 hr after ambulatory surgery: a survey of 5,703 patients. Can J Anesth. 2004;51:886–91.

Fahmy N, Siah J, Umo-Etuk J. Patient compliance with postoperative analgesia after day case surgery: a multisite observational study of patients in North East London. Br J Pain. 2016;10:84–9.

Gerbershagen HJ, Aduckathil S, van Wijck AJ, Peelen LM, Kalkman CJ, Meissner W. Pain intensity on the first day after surgery: a prospective cohort study comparing 179 surgical procedures. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:934–44.

Rai A, Meng H, Weinrib A, Englesakis M, Kumbhare D, Grosman-Rimon L, et al. A review of adjunctive CNS medications used for the treatment of post-surgical pain. CNS Drugs. 2017;31:605–15.

Martinez V, Beloeil H, Marret E, Fletcher D, Ravaud P, Trinquart L. Non-opioid analgesics in adults after major surgery: systematic review with network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118:22–31.

Tan M, Law LS, Gan TJ. Optimizing pain management to facilitate enhanced recovery after surgery pathways. Can J Anesth. 2015;62:203–18.

Memtsoudis SG, Poeran J, Zubizarreta N, Cozowicz C, Mörwald EE, Mariano ER, et al. Association of multimodal pain management strategies with perioperative outcomes and resource utilization: a population-based study. Anesthesiology. 2018;128:891–902.

Kumar K, Kirksey MA, Duong S, Wu CL. A review of opioid-sparing modalities in perioperative pain management: methods to decrease opioid use postoperatively. Anesth Analg. 2017;125:1749–60.

Lirk P, Badaoui J, Stuempflen M, Hedayat M, Freys SM, Joshi GP, for the PROSPECT group of the European Society for Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy (ESRA). PROcedure-SPECific postoperative pain management guideline for laparoscopic colorectal surgery. A systematic review with recommendations for postoperative pain management. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2024;41:161–73.

Brennan TJ. Pathophysiology of postoperative pain. Pain. 2011;152:S33–40.

Veenhof AA, Vlug MS, van der Pas MH, Sietses C, van der Peet DL, de Lange-de Klerk ES, et al. Surgical stress response and postoperative immune function after laparoscopy or open surgery with fast track or standard perioperative care: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2012;255:216–21.

Katz J, Clarke H, Seltzer Z. Review article: preventive analgesia: quo vadimus? Anesth Analg. 2011;113:1242–53.

Vadivelu N, Mitra S, Schermer E, Kodumudi V, Kaye AD, Urman RD. Preventive analgesia for postoperative pain control: a broader concept. Local Reg Anesth. 2014;7:17–22.

De Oliveira GS, Almeida MD, Benzon HT, McCarthy RJ. Perioperative single dose systemic dexamethasone for postoperative pain: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:575–88.

Favuzza J, Delaney CP. Outcomes of discharge after elective laparoscopic colorectal surgery with transversus abdominis plane blocks and enhanced recovery pathway. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:503–6.

Keller DS, Ermlich BO, Delaney CP. Demonstrating the benefits of transversus abdominis plane blocks on patient outcomes in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: review of 200 consecutive cases. J Am Coll Sur. 2014;219:1143–8.

Brogi E, Kazan R, Cyr S, Giunta F, Hemmerling TM. Transversus abdominal plane block for postoperative analgesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Can J Anesth. 2016;63:1184–96.

White PF, White LM, Monk T, Jakobsson J, Raeder J, Mulroy MF, et al. Perioperative care for the older outpatient undergoing ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:1190–215.

Grass F, Hübner M, Mathis KL, Dozolis EJ, Kelley SR, Demartines N, et al. Identification of patients eligible for discharge within 48 h of colorectal resection. Br J Surg. 2020;107:546–51.

Martin C, Auboyer C, Boisson M, Dupont H, Gauzit R, Kitzis M, et al. Steering committee of the French Society of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine (SFAR) responsible for the establishment of the guidelines. Antibioprophylaxis in surgery and interventional medicine (adult patients). Update 2017. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2019;38:549–62.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank, Nina Crowte, medical translator, for assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Marilyn Gosgnach: Conceptualization, Methodology, Original draft preparation, Discussing the results, Commenting the manuscript. Philippe Chasserant: Conceptualization, Methodology, Discussing the results, Commenting the manuscript. Mathieu Raux: Methodology, Formal analysis, Discussing the results, Commenting the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

It was approved by the relevant institutional review board (Comité d’Ethique pour la Recherche en Anesthésie Réanimation [CERAR] reference IRB 00010254–2018 – 188).

Consent for publication

not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it.The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gosgnach, M., Chasserant, P. & Raux, M. Opioid free analgesia after return home in ambulatory colonic surgery patients: a single-center observational study. BMC Anesthesiol 24, 260 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-024-02651-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-024-02651-1