Abstract

Background

Glutenin contents and compositions are crucial factors influencing the end-use quality of wheat. Although the composition of glutenin fractions is well known, there has been relatively little research on the genetic basis of glutenin fractions in wheat.

Results

To elucidate the genetic basis for the contents of glutenin and its fractions, a population comprising 196 recombinant inbred lines (RILs) was constructed from two parents, Luozhen No.1 and Zhengyumai 9987, which differ regarding their total glutenin and its fraction contents (except for the By fraction). Forty-one additive Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) were detected in four environments over two years. These QTL explained 1.3% - 53.4% of the phenotypic variation in the examined traits. Forty-three pairs of epistatic QTL (E-QTL) were detected in the RIL population across four environments. The QTL controlling the content of total glutenin and its seven fractions were detected in clusters. Seven clusters enriched with QTL for more than three traits were identified, including a QTL cluster 6AS-3, which was revealed as a novel genetic locus for glutenin and related traits. Kompetitive Allele-Specific PCR (KASP) markers developed from the main QTL cluster 1DL-2 and the previously developed KASP marker for the QTL cluster 6AS-3 were validated as significantly associated with the target traits in the RIL population and in natural varieties.

Conclusions

This study identified novel genetic loci related to glutenin and its seven fractions. Additionally, the developed KASP markers may be useful for the marker-assisted selection of varieties with high glutenin fraction content and for identifying individuals in the early developmental stages without the need for phenotyping mature plants. On the basis of the results of this study and the KASP markers described herein, breeders will be able to efficiently select wheat lines with favorable glutenin properties and develop elite lines with high glutenin subunit contents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Glutenins consist of high- and low-molecular-weight subunits (HMW-GS and LMW-GS), which are linked by disulfide bonds to form polymeric proteins in wheat [1]. The HMW-GS content is highly associated with dough viscoelasticity and bread-baking quality, despite only accounting for only about 7%-15% of the total protein in flour [2]. Additionally, HMW-GSs are encoded by three homologous loci located on the long arm of chromosome 1 in each genome (Glu-A1, Glu-B1 and Glu-D1) which contribute two tightly linked genes for x- and y- type subunits that are distinguished by molecular weights and the conserved N~terminal domain sequences [3, 4]. The LMW-GSs, which account for 60% of the total glutenins, are also major determinants of viscoelastic properties of dough [5]. The genetic loci related to LMW-GSs are Glu-A3, Glu-B3 and Glu-D3, which are located on the short arm of chromosome 1. In addition to these homologous loci, three new loci, Glu-2, Glu-4 and Glu-5, have been identified on chromosomes 1B, 1D and 7D, respectively [6, 7].

The various alleles at the HMW-GS and LMW-GS loci are responsible for the diverse combinations of subunits that contribute to the end-use quality of wheat [8]. For example, 1Dx5 + 1Dy10 (Glu-D1d), 1Bx7 + 1By8 (Glu-B1b), and 1Bx17 + 1By18 (Glu-B1i) lead to higher quality, whereas 1Dx2 + 1Dy12 (Glu-D1a), 1Bx20 (Glu-B1e), and 1Bx7 + 1By9 (Glu-B1c) are related to poor quality [9,10,11,12]. Interestingly, there are interactions between the Glu-1 loci and Glu-3 loci, implying there is a complex network controlling the composition and content of glutenin in wheat grains [13]. Additionally, modifying the contents of certain glutenin fractions induces properties changes in dough. More specifically, the absence of Dx2 decreases the dough quality through delaying glutenin polymerization [14]. In contrast, the over-expression of Ax1, Dx5 and Dy10 significantly increases glutenin polymers so as to improve the strength and elasticity of dough. Applying transgenic technologies to silence Dx5 significantly decreases the Zeleny sedimentation value, gluten index, and dough formation time and stability [15].

Quantitative trait loci (QTL) associated with the total glutenin, HMW-GS and LMW-GS contents have been detected, and the Glu-A1, Glu-B1, Glu-A3 and Glu-B3 genetic loci have been elucidated [16]. The QTL for Glu-B1x, Glu-D1x and Glu-D1y were mapped on chromosome 5A in wheat [17]. However, there have been relatively few studies on the QTL for these traits in wheat, with investigations restricted to low density markers in only a few environments. Little research has also been done to systematically identify genetic loci corresponding to the x- and y- type subunits of HMW-GS and to evaluate the allelic contributions in natural varieties. In the present study, a recombinant inbred line (RIL) population constructed from two parents, Luozhen No. 1 and Zhengyumai 9987, which differ regarding the quality and content of glutenin fractions, was used for dissecting QTL associated with total glutenin and seven fractions (HMW-GS, LMW-GS, Ax, Bx, By, Dx, and Dy) in four environments. We excluded Ay because the corresponding gene is usually silenced [18]. These QTL preferentially clustered in specific chromosomal regions. We subsequently developed and tested molecular markers for the two main QTL clusters. This research highlights the content of different glutenin fractions as a new aspect and strategy for quality improvement in wheat.

Results

Phenotypic variation and genetic effects of the parents and RILs

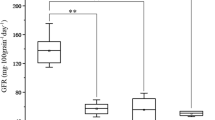

The contents of total glutenin and its seven fractions Ax, Bx, By, Dx, Dy, HMW-GS and LMW-GS were investigated in the parents and the RIL population under four environments (Table S1). The parent Luozhen No.1 had approximately twice as much glutenin as Zhengyumai 9987 (Fig. 1 and Table S2). The total glutenin and glutenin fractions (except for By) contents differed significantly between the two parents. The Ax, Bx, Dx, Dy and HMW-GS contents differed at the P < 0.01 level, whereas LMW-GS and total glutenin contents differed at the P < 0.05 level (Fig. 1 and Table 1). All traits were normally distributed in the RIL population (Fig. 2). In the two 2018 environments, the rank order for the relative abundance of each fraction was Bx> Dx > Ax> Dy > By, whereas in 2019, the rank order for the relative abundance was Bx > Dx > Dy > Ax > By in Yuanyang and Dx > Bx > Dy > Ax > By in Shangqiu (Fig. 2 and Table S2). The effects of the genotype, the environment and genotype-by-environment interactions significantly influenced all traits (P < 0.001) (Table 1). The broad-sense heritability of the traits was higher than 65%, with the exception of the By content, which was only 39.1% heritable (Table 1). All traits were significantly positively correlated with each other in all environments (P < 0.01). The correlation coefficient (r) between traits varied from 0.268 to 0.909. The highest correlation (r = 0.909) was between HMW-GS and Ax. The correlation between total glutenin and the glutenin fractions were lower (r =0.484 - 0.891) (Table S3).

Phenotypic divergence between the two parents in four environments. The average values of each fraction are indicated on the y-axis. Significant differences between the parents are indicated (* P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01). Only the By content did not differ significantly between the two parents of the RIL population

Phenotypic variations of each glutenin fraction in the RIL population in different environments. The phenotypic distribution of each glutenin fraction in the RIL population in four environments is presented. The four different environments are indicated on the left side and the different colored dots and bars represent different traits

Genetic loci controlling the total glutenin and its fraction contents

A total of 41 additive QTL related to the total glutenin and its fraction contents were detected (Fig. 3 and Table S4). These QTL were distributed on 16 chromosomes: 1A (2 QTL), 1B (2 QTL), 1D (6 QTL), 2B (2 QTL), 3A (4 QTL), 3B (1QTL), 3D (5 QTL), 4A (3 QTL), 4D (2 QTL), 5A (2 QTL), 5B (1 QTL), 6A (3 QTL), 6D (2 QTL), 7A (2 QTL), 7B (2 QTL) and 7D (2 QTL) (Fig. 3, Table S4 and Figure S1-7). Individual QTL explained 1.3%-53.4% of the phenotypic variation, with the logarithm of the odds (LOD) ranging from 2.54 to 39.7 (Table S4). Regarding the individual traits, 10 (Ax), 7 (Bx), 8 (By), 10 (Dx), 9 (Dy), 4 (HMW-GS), 14 (LMW-GS) and 11 (total glutenin) QTL were detected (Table S4 and Figure S4).

Distribution of QTL associated with total glutenin and its fractions content on the physical map. The QTL represented by black bars are marked according to the physical position on the map. The physical positions are indicated to the left of the first chromosome in each row. The marker names are provided to the right of each chromosome. The QTL associated with different traits are assigned different colors (legend in the lower right corner). The red bars indicate the centromeres positions

The eleven QTL related to the total glutenin content were detected on chromosomes 1D (2 QTL), 2B (1 QTL), 3A (2 QTL), 4D (1 QTL), 6A (1 QTL), 6D (2 QTL), 7B (1 QTL) and 7D (1 QTL), respectively, explained 2.3%-26.9% of the phenotypic variation. Four QTL, QGlu.1DL-2, QGlu.3AS-2, QGlu.4DS and QGlu.6AS-3, were repeatedly detected in more than three environments (BLUP included) (Table S4 and Figure S1). Some environment-specific QTL were also detected, among which six and one were detected only in E2 and E3, respectively (Table S4 and Figure S1).

Four HMW-GS related QTL were detected, among which two (QHMW.1DL-2 and QHMW.6AS-3) were identified in all environments, one (QHMW.1AS-1) was identified in two environments (BLUP included), and another (QHMW.3AL-2) was E2-specific (Table S4 and Figure S2). Individual loci contributed 4.0%-24.4 % to the phenotypic variation. However, the five fractions, Ax, Bx, By, Dx, and Dy, seemed quite susceptible to environmental conditions. Although there were 10, 7, 8, 9 and 9 QTL associated with Ax, Bx, By, Dx and Dy, respectively, most of these were environment-specific QTL. Hence, only nine QTL were repeatedly detected in more than three environments (BLUP included) (Table S4 and Figures S4-7). One of the QTL located in the Whass16441-Whass16657 marker interval on chromosome 1D was associated with all glutenin fractions and contributed up to 53.4% of the phenotypic variation in the By content (Fig. 3 and Table S4).

Fourteen QTL associated with LMW-GS were distributed on 10 chromosomes (Figure S3). Four of these QTL (QLMW.1DS-1, QLMW.1DL-2, QLMW.3AS-2 and QHMW.6AS-3) explained 3.1% - 22.2% of the phenotypic variation with a LOD of 2.66-15.28 and were detected in more than three environments (BLUP included). The other QTL were specific to certain environments (Table S4 and Figure S3).

Detection of epistatic QTL for all traits

Forty-three pairs of epistatic QTL (E-QTL) were detected for total glutenin and its fractions in the RIL population across four environments (Table S5 and Fig. 4). More specifically, 9, 5, 1, 10, 7, 7 and 4 E-QTL detected for total glutenin, HMW-GS, LMW-GS, Dy, By, Dx and Bx, respectively. These E-QTL were estimated to explain 2.61% – 11.18% of the phenotypic variation. No E-QTL was detected for Ax (Table S5 and Fig. 4). Of the E-QTL, seven were detected in two environments, whereas two were revealed in three environments (Table S5). The QTL interval flanked by the molecular markers Whass24363 and Whass24444 on chromosome 2B revealed for total glutenin and Ax (QGlu.2BS-2and QAx1.2BS-1 in E2) was estimated involving the interaction with the QTL region anchored between Whass120631 and Whass120491 on chromosome 6A.

E-QTL for total glutenin and its fractions in the RIL population across four environments. The E-QTL interval pairs are linked by curves. Seven colors were used to represent the E-QTL for different glutenin fractions (legends in the lower right corner). Chromosomes are represented by grey bars. The bar length reflects the relative length of each chromosome

Dissection of the QTL clusters

All forty-one QTL were mapped on the physical map constructed according to the sequence information derived from the specific locus amplified fragment (SLAF) tag and aligned with the reference genome sequence. Some QTL controlling the total glutenin and its fraction contents tended to co-localize on particular chromosomes (Fig. 3 and Figures S8-11). Seven regions enriched with QTL for more than three traits were designated as QTL clusters, which were distributed on the regions of 1AS-1, 1BL-1, 1DL-2, 1DL-3, 3AS-2, 4DS and 6AS-3 (Fig. 3 and Figures S8-11). The 1DL-2 QTL cluster controlled all eight traits (Fig. 5), whereas 6AS-3 included QTL affecting seven traits; the exception was the By fraction content (Fig. 3).

QTL cluster for total glutenin and its fraction contents detected on 1DL. The QTL cluster on 1DL was associated with all eight investigated traits. Curves with different colors indicate different traits. Molecular markers around the peak of the cluster and their corresponding genetic positions are labeled. The major locus for controlling the glutenin content, Glu-D1 (purple), was mapped in this cluster. Two SNPs flanking the cluster, which were used for developing and validating KASP markers are in red

Candidate gene analysis for the two main QTL clusters

A total of 164 annotated genes were identified from the two main QTL clusters, 1DL-2 and 6AS-3, with the chromosome region on 1DL (409.26-416.45Mb) and 6AS (44.02-50.35Mb) (Table S6). Among them, 112, 53, 49 and 103 annotated genes had identified in the GO, KEGG, KOG and Swiss-prot database, respectively (Table S6). By GO analysis, 22 genes were detected in the cellular component category, 37 genes in the molecular function category, and 19 genes in the biological process category (Table S6 and Figure S12). Through KEGG analysis, 53 genes were detected in 29 pathways (Table S6 and Figure S13). In the KOG analysis, only two genes had unknown function (Table S6 and Figure S14). Among other genes, eight genes were related with posttranslational modification, protein turnover and chaperones, and four of them had a relation to transcription.

Contribution of the two main QTL clusters to phenotypic variation

In this study, KASP markers were developed from two SNPs. Specifically, Whaas16493 was derived from the SNP which underlying the overlapping region of the QTL cluster 1DL-2 for glutenins and for gluten aggregation properties reported by our previous study) [19], whereas Whaas115399 was located in the QTL cluster regions 6AS-3 (Table S7). These markers were used for evaluating the contribution of these regions to total glutenin and its fraction contents in the RIL population and in a set of 207 natural varieties (Tables S8-S10). In the RIL population, the lines with Whass16493-G and Whass115339-A had significantly higher total glutenin and its fraction contents than the lines with Whass16493-A and Whass115339-G which was as expected considering the additive effect of two parents (Table S9). Moreover, some lines harbored recombined genotypes in Whass16493 and Whass115339. The lines with Whaas16493-A + Whaas115399-G, Whaas16493-A + Whaas115399-A, Whaas16493-G + Whaas115399-G or Whaas16493-G+ Whaas115399-A differed significantly in terms of the total glutenin and LMW-GS, Dx and Dy contents (Table S9). An evaluation of the genetic effects in the natural population revealed Whass16493 influenced the content of glutenin fractions more than Whaas115399. Additionally, there was no significant difference in the effects of the Whaas115399-A and Whaas115399-G alleles among the varieties (Fig. 6, Tables S8 and S10). However, similar to the effects observed in the RIL population, the glutenin fraction content was higher for Whass16493-A than for Whaas16493-G (Fig. 6, Tables S8-10).

Effects of two SNP loci on glutenin fractions in a set of bread wheat cultivars. The effects of two SNPs on the content of glutenin fractions in 207 wheat varieties are presented. The genotypes labeled under each chart are for the SNPs Whaas16493 and Whaas115399. The y-axis indicates the content of each trait. Significance differences among the various genotypes are indicated by lowercase letter (P < 0.05; ANOVA)

Discussion

Although the glutenin content is significantly influenced by environment, this trait is mainly controlled by genetic factors. We identified genetic loci controlling total glutenin and its fraction contents via a QTL analysis, which revealed 41 QTL distributed on 16 chromosomes in an F6 RIL population over the 2-year investigation. Eight QTL associated with the glutenin content were revealed on chromosomes 1A, 1B, 1D, 3A, 4A and 5D. In addition to Glu1A, Glu1B and Glu1D, which were previously characterized as functional loci controlling the HMW-GS content in wheat, we also detected other loci located on chromosomes 5A, 2B, 7A and 5D known to contribute to the HMW-GS content [16, 17]. The main QTL related to the LMW-GS were located on chromosomes 1A, 1B, 1D, 2B, 3A, 5D, 7A and 7D [16, 17]. As predicted, QTL controlling the HMW-GS content were detected on the long arm of chromosome 1D, whereas the QTL for the LMW-GS content were present on the short arm of chromosomes 1A and 1D. The QTL on 1AS and 1DL control both HMW- and LMW-GS. The major QTL cluster 1DL-2 between markers Whass16441 and Whass16657 revealed in the present study partially overlapped the QTL cluster associated with gluten aggregation between markers Whaas16407 and Whaas16588 which we detected in an earlier study in which the Glu-D1 was considered as the most likely candidate gene for the QTL cluster [19]. However, QTL were not detected on 1AL and 1BL for HMW-GS or on 1BS for LMW-GS. Additionally, QTL for HMW-GS were also detected on 3AL, 6AS and 7BS, whereas QTL for LMW-GS were detected on 3AS, 3AL, 3DL, 4DL, 5AL, 5BL, 6AS, 7BS and 7DS. Although relatively few studies have systematically assessed genetic loci affecting Ax (and Ay), Bx, By, Dx and Dy content, QTL associated with Bx and Dy have previously been mapped on chromosome 1B, and QTL associated with Dx have been located on chromosomes 1B and 5A [17]. The QTL cluster 6AS-3, which included QTL controlling seven glutenin fractions (i.e., except for By), was not identified by previous studies. A comparison of the protein content-related QTL revealed in common and tetraploid wheat indicated QTL were distributed on 2A, 2B, 3A, 4BS, 4D, 5AL, 6AS, 6BS, 7AS, 7BS, 7BL and 7D [20]. To date, no QTL has been detected in a physical position similar to that of the QTL cluster 6AS-3. More interestingly, the QTL cluster 6AS-3 is a pleiotropic locus that controls the content of total glutenin, GMW-GS, LMW-GS, Ax, Bx, Dx and Dy, and contributes to 3.1%-13.8% of the phenotypic variation for these traits. The detection of the QTL cluster 6AS-3 may provide a promising approach for improving all glutenin fraction contents at the same time by manipulating a single locus.

The QTL controlling the total glutenin and its fraction contents tended to cluster at the same physical positions in the genome. The seven QTL clusters detected in this study contained 32 of the 41 QTL detected for individual traits. The genes underlying these QTL clusters may function to increase the contents of all glutenin fractions. Previous studies revealed that in addition to allelic variations of glutenin synthesis genes, transcription factors may play an important role in regulating the expression of genes related to glutenin and its fractions. For example, a G-box element located in the promoter region of HMW-GS Dx5 can initiate gene-specific expression in the endosperm [21]. These elements can also be specifically recognized and interact with different transcription factors that regulate the expression of HMW-GS and LMW-GS genes. More specifically, SPA transcription factors in the bZIP family can bind to the GCN4-like motif in the LMW-GS gene promoter to increase the expression level of this gene in wheat [22]. Additionally, the NAC family transcription factor TaNAC100 significantly increases the expression level of genes located downstream of the Glu-1 promoter [23]. The By15, Dx2 and Dy12 contents as well as the total HMW-GS content significantly increase in transgenic lines over-expressing TaNAC100 [23]. Epigenetic modifications are also an important molecular mechanism for the regulation of the glutenin synthesis genes [24]. The histone acetyltransferase TaGCN5 interacts with the TaGAMyB transcription factor and together they bind to the promoter region of the HMW-GS genes, causing an increase in gene expression [25]. Our present study identified two major QTL clusters: 1DL-2 contributing to all eight investigated traits and 6AS-3 contributing to seven of the investigated traits (the exception was By). Other QTL clusters affected more than three traits. The genes in these pleiotropic QTL clusters may not be known genes for HMW-GS or LMW-GS genes, but they may encode other factors, perhaps including transcription factors or divergent chromatin status. We conclude that the synthesis and regulation of glutenin and its fractions involve a complex spatially and temporally specific network that will need to be further investigation.

Of the three HMW-GS loci located in the homologous regions of chromosome 1 (Glu-1), Glu-D1 had the biggest impact on quality in wheat [26, 27]. The compositions of the subunits encoded by Glu-D1 exert divergent effects on viscoelasticity and strength of dough [28, 29]. The rank order of the contribution of different subunits to dough strength is commonly assumed to be as follows: Dx5 + Dy10 > Dx2 + Dy12 > Dx3 + Dy12 > Dx4 + Dy12 [30]. An earlier study indicated that the bread-baking quality is greater for Dx2 + Dy12 than for Dx5 + Dy10 [31]. This phenomenon may derive from the higher content of Dx2 + Dy12 subunits according to the higher accumulation rate of the polymer and the higher proportion of polymer protein relative to monomer protein in the grain, which confers stronger gluten qualities [32]. Although the x- and y- type subunits of HMW-GS are tightly linked, there are also varieties containing recombinant subunits [31]. The recombinant subunit Dx5 + Dy12 confers higher baking quality than that of Dx5 + Dy10 and Dx2 + Dy12 [30, 32]. In the Glu-B1 and Glu-A1 loci, the contributions of different subunit compositions are as follows: Bx17 + By18 > Bx13 + By16 > Bx7 + By9 > Bx7 + By8 > Bx6 + By8 and Ax2* > Ax1 > Null, respectively [33,34,35]. In the present study, subunit-specific QTL for Ax (2BS-1, 3BL, 4AS, 4AL-1 and 4AL-2), Dx (1AS-2, 1BL-2 and 7AS-2), QDy (1DS-3, 5AL-2, 6AS-2), QBy (3DL-1, 7AS-1) and Bx (6AS-1) were detected. These results provide a possibility for selecting and creating germplasm harboring specific recombinant subunits as required. Production of lines with different x- and y- subunits through pyramiding of subunit-specific genetic loci may be facilitated by molecular markers for the specific glutenin fraction variants.

Conclusions

In the present study, forty-one additive QTL and forty-three pairs of E-QTL associated with total glutenin and glutenin fraction contents were detected in a RIL population in four environments across two years. The detected QTL anchored to seven clusters which controlling more than three traits, whereas the QTL cluster 6AS-3 was recognized as a novel genetic locus. Two KASP markers for the two main QTL clusters 1DL-2 and 6AS-3 which can be used to effectively evaluate the content of glutenin fractions in the progeny of the two original parents as well as in natural wheat varieties. In practice, it is preferable to have more information about variants present for each gene related to quality in individual lines and to be able to evaluate the contributions of these variants to quality improvement. These two KASP markers can be used for marker-assisted selection of varieties with high glutenin fraction contents and for selecting individuals at the early developmental stages without needing to phenotype mature plants. This will increase the efficiency of selection and facilitate the creation of elite lines with high glutenin subunit contents for quality improvement in wheat.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growing environments

The mapping population consists of 196 F6 Recombinant Inbred Lines (RILs) derived from two common wheat cultivars, Luozhen No.1 and Zhengyumai9987, which were originally provided by the Luohe Academy of Agricultural Sciences and the Youbang Crop Breeding Institute in Zhengzhou, respectively [19]. The two parents are divergent in quality related traits, not only in composition of glutenin but also in the quantity of each fraction of storage protein.

The RIL population was planted in the field experimental station of Henan Academy of Agricultural Science in Yuanyang (YY, E113°97′, N35°05′) and Yanjin (YJ, E114°36′, N35°10′) in 2017 – 2018, and in Yuanyang and Shangqiu (SQ, E115° 65′, N34° 45′) in 2018 – 2019. These cities are located in Henan province, which is the main wheat growing region in China. Each line was planted in a plot with two rows of 2 by 0.3 m, with 10 cm spaces between adjacent plants. Seeds were sown in October and the plants were harvested in May of the next year with normal treatments during the whole developmental period. A panel of 207 cultivars, collected from the Henan Province Crop Germplasm Bank and The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) [36, 37] were also planted in the same environments in order to investigate whether the RIL results to a wider panel of cultivars. The authors declare the total permissions to use the collections.

Glutenin extraction

The glutenins were extracted from 45 mg flour according to a published protocol [38] of with minor modifications. During the extraction procedure, 7% N-propanol (with 0.3M NaI), 70% ethanol and 50% isopropanol were used sequentially and the liquid glutenin extractions were filter-sterilized. Two replicates of each line were prepared for extraction.

Measuring glutenin quantity and fractions

A reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) system (Waters E2695+2998DAD,Waters Corporation, MA USA) with chromatographic column Vydac 218TP C18 (250mm × 4.6mm) was used for measuring glutenin quantity and fractions within 200 μl extractions [39]. The parameters were set as follows: the elution flow rate of elution was 0.8 ml/minute, the elution gradient was 0-10 minutes, 90% elution A (0.06% TFA solution in ddH2O) and 10% elution B (0.05% TFA solution in acetonitrile); elution A was linear decreasing to 35% within 10-65minutes, and the column temperature was 60°C. The content of each fraction was calculated according to the area value of corresponding peaks as follows:

Yu (106AU/mg): content of each fraction; M (mg): weight of sample for extraction; X (%): water content of wheat flour measured by near infrared spectrum analyzer; Tu (AU): the peak area of each fraction; *100: 10 μl extraction was run on the RP-HPLC while the total extraction was 1 ml.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using various sets of tools or software packages. Significance was calculated by the t-test module of Microsoft Office Excel. The phenotypic description parameters, such as variation, mean value, standard deviation, coefficient of variation, were analyzed using the “psych” package of R (version 3.5.3) (R Core Team 2020). BLUP (Best Linear Unbiased Prediction) and broad-sense heritability for each trait were calculated by the “Lme4” package in R. Phenotypic variations and correlations were analyzed by SAS 9.2 and IBM SPSS Statistics 22, respectively.

Construction of the genetic map

The SLAF (Specific Locus Amplified Fragment Sequencing) technology was used for mining SNPs (Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms) between the two parents and in the RILs. The mLOD between SLAF tags was calculated and used to distinguish different linkage groups. The HighMap software was used for evaluating the genetic distance between SLAF tags according to Maximum Likelihood Estimation and arranging their order in each linkage group. A total of 1,544.06 M reads were obtained, of which 90.37% of reads were pair-end aligned with the reference genome sequence [40]. Finally, a genetic map was constructed with 8,942 total SNPs located on 21 linkage groups. The total genetic length was 3,140.54 cM and the average genetic distance between two adjacent markers was 0.35 cM.

Analysis of QTL and epistatic QTLs

The software package “QTL.gCIMapping.GUI” in R was used for QTL mapping. The genetic map constructed by SLAF tags and all RIL phenotype data was imported into the software, which was run as follows: data format = GCIM, logarithm of the odds (LOD) score = 2.5 for the random model used for QTL screening. The additive-by-additive E-QTL were analyzed using QTL IciMapping software. More specifically, the ICIM-EPI method was used with the mapping parameters set as follows: step (cM): 25; probability in stepwise regression: 0.0001; LOD Threshold 1.000 [41, 42].

Candidate gene analysis for the two main QTL clusters

The confidence intervals of the QTL clusters which can be identified with seven or more surveyed traits were selected to detect the candidate genes. Based on the physical position of flanking markers according to the Chinese Spring reference genome (IWGSC v1.1), all genes harbored in the confidence intervals were regarded as the candidate genes. All the annotated candidate genes were categorized through Gene Ontology (GO), the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), eukaryotic orthologous groups (KOG) and the Swiss-prot database analysis.

KASP marker development

Genomic sequences with a length of 100 bp on the 5′ and 3′ strands surrounding the target SNP were extracted. Two allele-specific primers were designed carrying the FAM: (5′-TGAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCT3-′) and HEX: (5′- GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATT 3-′) sequences at the 5′ end. The target SNP was anchored at the 3′ end of each primer. The sequences from which the target SNPs were derived were used to identify homologous sequences via BLAST using the website EnsemblPlants database (http://plants.ensembl.org/index.html). Five to eight sequences with the highest homology were selected. These sequences were aligned and the conserved regions were used for designing allele-specific primer pairs. The PCR reactions were prepared using the KASP Assay mixture and a Bio-Rad CFX Maestro was used for fluorescence detection and data analysis.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files] and the raw SLAF sequencing data can be found in Genome Sequence Archive (https://bigd.big.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA003543).

Abbreviations

- RILs:

-

Recombinant Inbred Lines

- QTL:

-

Quantitative Trait Loci

- KASP:

-

Kompetitive Allele-Specific PCR

- HMW-GS:

-

High Molecular Weight Subunits

- LMW-GS:

-

Low Molecular Weight Subunits

- LOD:

-

Logarithm of the Odds

- BLUP:

-

Best Linear Unbiased Prediction

References

Anjum FM, Khan MR, Din A, Saeed M, Pasha I, Arshad MU. Wheat gluten: high molecular weight glutenin subunits--structure, genetics, and relation to dough elasticity. J Food Sci. 2007;72(3):R56–63.

Li Y, An X, Yang R, Guo X, Yue G, Fan R, et al. Dissecting and enhancing the contributions of high-molecular-weight glutenin subunits to dough functionality and bread quality. Mol Plant. 2015;8(2):332–4.

Payne PI, Holt LM, Worland AJ, Law CN. Structural and genetical studies on the high-molecular-weight subunits of wheat glutenin : Part 3. Telocentric mapping of the subunit genes on the long arms of the homoeologous group 1 chromosomes. Theor Appl Genet. 1982;63(2):129–38.

Shewry PR, Halford NG, Lafiandra D. Genetics of wheat gluten proteins. Adv Genet. 2003;49:111–84.

Bietz JAHF, Sanderson JE, Wall JS. Wheat gliadin homology revealed through N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis. Cereal Chem. 1977;54:1070–83.

Jackson EA, Holt LM, Payne PI. Glu-B2, a storage protein locus controlling the D group of LMW glutenin subunits in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum). Genetics Res. 1985;46:11–7.

Liu CY, Shepherd KW. Variation of B subunits of glutenin in durum, wild and less-widely cultivated tetraploid wheats. Plant Breeding. 1996;115(3):172–8.

Ravel C, Faye A, Ben-Sadoun S, Ranoux M, Dardevet M, Dupuits C, et al. SNP markers for early identification of high molecular weight glutenin subunits (HMW-GSs) in bread wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2020;133(3):751–70.

Gianibelli MC, Larroque OR, Macritchie F, Wrigley CW. Biochemical, Genetic, and Molecular Characterization of Wheat Glutenin and Its Component Subunits. Cereal Chem. 2001;78(6):635–46.

Shewry PR, Halford NG, Tatham AS. High molecular weight subunits of wheat glutenin. J Cereal Sci. 1992;15(2):105–20.

Peihong J, Jiesheng X, Luning D, Yunsong G, Junyi M. Effects of high-molecular-weight glutenin subunit combination in common wheat on the quality of crumb structure. J Sci Food Agric. 2018;99(4):1501–8.

Weegels LP. Depolymerisation and re-polymerisation of wheat glutenin during dough processing and effects of low Mr wheat proteins: King's College London (University of London); 1994.

Krystkowiak K, Langner M, Adamski T, Salmanowicz BP, Surma M. Interactions between Glu-1 and Glu-3 loci and associations of selected molecular markers with quality traits in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) DH lines. J Appl Genetics. 2017;58(1):37–48.

Song L, Li L, Zhao L, Liu Z, Xie T, Li X. Absence of Dx2 at Glu-D1 Locus Weakens Gluten Quality Potentially Regulated by Expression of Nitrogen Metabolism Enzymes and Glutenin-Related Genes in Wheat. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(4):1383.

Yue SJ, Li H, Li YW, Zhu YF, Guo JK, Liu YJ, et al. Generation of transgenic wheat lines with altered expression levels of 1Dx5 high-molecular weight glutenin subunit by RNA interference. J Cereal Sci. 2008;47(2):153–61.

Zhang Y, Tang J, Zhang Y, Yan J, Xiao Y, Zhang Y, et al. QTL mapping for quantities of protein fractions in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2011;122(5):971–87.

Guillaumie S, Charmet G, Linossier L, Torney V, Robert N, Ravel C. Colocation between a gene encoding the bZip factor SPA and an eQTL for a high-molecular-weight glutenin subunit in wheat (Triticum aestivum). Genome. 2004;47(4):705–13.

Gutiérrez M, Guzmán C, Martín L, Alvarez JB. Molecular characterization of the Glu-Ay gene from Triticum urartu for its potential use in quality wheat breeding. Plant Genetic Resour. 2011;9(2):334–7.

Zhou Z, Zhang Z, Jia L, Qiu H, Guan H, Liu C, et al. Genetic Basis of Gluten Aggregation Properties in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Dissected by QTL Mapping of GlutoPeak Parameters. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:611605.

Groos C, Robert N, Bervas E, Charmet G. Genetic analysis of grain protein-content, grain yield and thousand-kernel weight in bread wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2003;106(6):1032–40.

Norre F, Peyrot C, Garcia C, Rancé I, Drevet J, Theisen M, et al. Powerful effect of an atypical bifactorial endosperm box from wheat HMWG-Dx5 promoter in maize endosperm. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;50(4-5):699–712.

Boudet J, Merlino M, Plessis A, Gaudin JC, Dardevet M, Perrochon S, et al. The bZIP transcription factor SPA Heterodimerizing Protein represses glutenin synthesis in Triticum aestivum. Plant J. 2019;97(5):858–71.

Li J, Wang K, Li G, Li Y, Zhang Y, Liu Z, et al. Dissecting conserved cis-regulatory modules of Glu-1 promoters which confer the highly active endosperm-specific expression via stable wheat transformation. Crop J. 2019;7(01):8–18.

Zhou Z, Liu C, Qin M, Li W, Wu Z. Promoter DNA hypermethylation of TaGli-γ-2.1 positively regulates gluten strength in bread wheat. J Adv Res. 2021; Available online; doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2021.06.021.

Guo W, Yang H, Liu Y, Gao Y, Ni Z, Peng H, et al. The wheat transcription factor TaGAMyb recruits histone acetyltransferase and activates the expression of a high-molecular-weight glutenin subunit gene. Plant J. 2015;84(2):347–59.

Wang Z, Li Y, Yang Y, Liu X, Qin H, Dong Z, et al. New insight into the function of wheat glutenin proteins as investigated with two series of genetic mutants. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3428.

Yang Y, Li S, Zhang K, Dong Z, Li Y, An X, et al. Efficient isolation of ion beam-induced mutants for homoeologous loci in common wheat and comparison of the contributions of Glu-1 loci to gluten functionality. Tagtheoretical Applied Geneticstheoretische Und Angewandte Genetik. 2014;127(2):359–72.

Hernández-Estrada ZJ, Rayas-Duarte P, Cárdenas JDF. Creep Recovery of Wet Gluten and High-Molecular-Weight Glutenin Subunit Composition: Relationship with Viscoelasticity of Dough and Breadmaking Quality of Hard Red Winter Wheat. Cereal Chem. 2017;94(2):223–9.

Zhang Y, Hu M, Liu Q, Sun L, Chen X, Lv L, et al. Deletion of high-molecular-weight glutenin subunits in wheat significantly reduced dough strength and bread-baking quality. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18(1):319.

Payne PI, Lawrence GJ. Catalogue of alleles for the complex gene loci, Glu-A1, Glu-B1, and Glu-D1 which code for high-molecular-weight subunits of glutenin in hexaploid wheat. Cereal Res Commun. 1983;11(1):29–35.

Wrigley CW, Lawrence GJ, Shepherd KW. Association of Glutenin Subunits With Gliadin Composition and Grain Quality in Wheat. Functional Plant Biol. 1982;9(1):15–30.

Shewry PR, Halford NG, Tatham AS, Popineau Y, Belton PS. The high molecular weight subunits of wheat glutenin and their role in determining wheat processing properties. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2003;45(03):219–302.

Li S, Pei A, Dong B, Liu Y. Effect of 1BL/1RS Translocation on Wheat Quality Breeding of Shaanxi Province. J Triticeae Crops. 2005;025(006):40–3.

Patil VR, Talati JG, Singh C, Parekh VB, Jadeja GC. Genetic Variation in Glutenin Protein Composition of Aestivum and Durum Wheat Cultivars and Its Relationship with Dough Quality. Int J Food Properties. 2015;18(9-12):2393–408.

Zhang Y, Tang J, Yan J, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Xia X, et al. The gluten protein and interactions between components determine mixograph properties in an F6 recombinant inbred line population in bread wheat. J Cereal Sci. 2009;50(2):219–26.

Zhou Z, Shi X, Zhao G, Qin M, Wang J. Identification of Novel Genomic Regions and Superior Alleles Associated With Zn Accumulation in Wheat Using A Genome-Wide Association Analysis Method. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(6):1928.

Liu C, Zhou Z, Wu Z, Qin M, Shi X, Wang Y, et al. In-depth genetic analysis reveals conditioning of polyphenol oxidase activity in wheat grains by cis regulation of TaPPO2A-1 expression level. Genomics. 2020;112(6):4690–700.

Dupont FM, Chan R, Lopez R, Vensel WH. Sequential extraction and quantitative recovery of gliadins, glutenins, and other proteins from small samples of wheat flour. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53(5):1575–84.

González-Torralba J, Arazuri S, Jarén C, Arregui LM. Stable Quality Traits of Soft Winter Wheat under Nonlimiting Nitrogen Conditions. Crop Sci. 2011;51(6):2820–8.

Sun S, Zhou Y, Chen J, Shi J, Zhao H, Zhao H, et al. Extensive intraspecific gene order and gene structural variations between Mo17 and other maize genomes. Nat Genet. 2018;50(9):1289–95.

Li H, Ye G, Wang J. A modified algorithm for the improvement of composite interval mapping. Genetics. 2007;175(1):361–74.

Li H, Ribaut JM, Li Z, Wang J. Inclusive composite interval mapping (ICIM) for digenic epistasis of quantitative traits in biparental populations. Theor Appl Genet. 2008;116(2):243–60.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by the NationalKey Research and Development Program of China (2017YFD0100704), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy - EXC 2070 - 390732324, the Scientific and Technological Research Project of Henan Province (202102110027), the Scientific and Technological Innovation Project of Henan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2020CX01), and Outstanding youth fund of Henan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2021JQ04) .

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZL, ZW and JH designed and supervised the study. ZfZ, ZwZ and CL investigate the content of glutenin and the fractions. JH, ZwZ, AM and BT conducted data analysis. ZfZ wrote the manuscript. JH and AM revised the manuscript. ZfZ, MQ and WL developed the RIL population and constructed the genetic mapped. WL conducted the field experiment. All the authors discussed the results and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest/competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1

Phenotypic data of all the traits under all the four environments. Table S2 Phenotypic variation of two parents and RIL population in four environments and the average value. Table S3 The correlation coefficient between different traits. Table S4 QTL associated with content of glutenin and its fractions in a bread wheat RIL population across four environments. Table S5 E-QTL for total glutenin and its fractions in four environments of the RIL population. Table S6 List of 164 annotated genes located in the two main QTL clusters of 1DL-2 and 6AS-3. Table S7 Sequence for KASP markers development. Table S8 Genotyping by two KASP markers and glutenin and its fractions content in natural accessions. Table S9 Additive effect analysis of two KASP markers for glutenin content and fractions in the RIL population. Table S10 Additive effect analysis of the significant SNPs on major QTL clusters associated with content of glutenin subunits fractions in natural population.

Additional file 2: Figure S1.

QTL detected for the content of total glutenin. E1, E2, E3 and E4 represent the environments of Yuanyang (2018), Yanjin (2018), Yuanyang (2019), Shangqiu (2019), respectively. BLUP represents the QTL analysis with best linear unbiased prediction. The red peak represent the QTL screened. The name of each QTL assigned according to nomenclature were labeled. Figure S2. QTL detected for HMW-GS content. Legends accordingly with Figure S1. Figure S3. QTL detected for LMW-GS content. Legends accordingly with Figure S1. Figure S4. QTL detected for Ax content. Legends accordingly with Figure S1. Figure S5. QTL detected for Bx content. Legends accordingly with Figure S1. Figure S6. QTL detected for By content. Legends accordingly with Figure S1. Figure S7. QTL detected for Dy content. Legends accordingly with Figure S1. Figure S8. QTL cluster for glutenin and its fractions detected in 1AS-1 region. Curves with different colors indicated different traits. Molecular markers around the peak of the cluster and their corresponding genetic position were labeled. The major locus for controlling glutenin content, Glu-D1 which coloured with purple, was mapped in this cluster. Two SNPs flanking the cluster which were used for KASP marker development coloured in red. Figure S9. QTL cluster for glutenin and its fractions detected in 1BL-1 region. Legends accordingly with Figure S8. Figure S10. QTL cluster for glutenin and its fractions detected in 1DL-3 region. Legends accordingly with Figure S8. Figure S11. QTL cluster for glutenin and its fractions detected in 3AS-2 region. Legends accordingly with Figure S8. Figure S12. GO analysis of the annotated candidate genes in the two main QTL clusters. Figure S13. KEGG analysis of the annotated candidate genes in the two main QTL clusters. Figure S14. KOG analysis of the annotated candidate genes in the two main QTL clusters.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Z., Zhang, Z., Mason, A.S. et al. Quantitative traits loci mapping and molecular marker development for total glutenin and glutenin fraction contents in wheat. BMC Plant Biol 21, 455 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-021-03221-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-021-03221-0