Abstract

Background

Thermotolerance is a highly desirable trait of microbial cell factories and has been the focus of extensive research. Yeast usually tolerate only a narrow temperature range and just two species, Kluyveromyces marxianus and Ogataea polymorpha have been described to grow at reasonable rates above 40 °C. However, the complex mechanisms of thermotolerance in yeast impede its full comprehension and the rare physiological data at elevated temperatures has so far not been matched with corresponding metabolic analyses.

Results

To elaborate on the metabolic network response to increased fermentation temperatures of up to 49 °C, comprehensive physiological datasets of several Kluyveromyces and Ogataea strains were generated and used for 13C-metabolic flux analyses. While the maximum growth temperature was very similar in all investigated strains, the metabolic network response to elevated temperatures was not conserved among the different species. In fact, metabolic flux distributions were remarkably irresponsive to increasing temperatures in O. polymorpha, while the K. marxianus strains exhibited extensive flux rerouting at elevated temperatures.

Conclusions

While a clear mechanism of thermotolerance is not deducible from the fluxome level alone, the generated data can be valued as a knowledge repository for using temperature to modulate the metabolic activity towards engineering goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

For centuries, yeasts have been essential to many applications for the betterment of human life. With the rise of metabolic engineering and due to manifold beneficial traits, ranging from ethanol tolerance to protein glycosylation, these organisms have also found various applications outside the baking and beverage industries [1, 2]. While the engineering of microbial strains for biotechnological processes has profited intensively from rapid advances in the accuracy, applicability, and availability of genetic engineering tools, rational strain development must be based on comprehensive knowledge on genomics, physiology, and metabolism [3, 4]. Metabolic flux analysis provides the means for the necessary exploration of the intracellular metabolic network operation beyond measuring growth, substrate consumption, and metabolite secretion [5,6,7].

Thermotolerance is a rare trait among yeasts, but has been described for few species and was improved for example in baker’s yeast [8, 9]. Thermotolerant yeasts have been applied in industrial processes but not exclusively for the reason of thermotolerance [10, 11]. While a general interest in thermotolerant strains can be raised from universal process requirements, like less expensive cooling and lower risk of contamination, a popular process example that would benefit extensively from thermotolerant strains is the production of second-generation bioethanol [12]. Kluyveromyces marxianus (synonym: Candida macedoniensis) and Ogataea polymorpha (synonyms: Hansenula polymorpha, Candida thermophila, Pichia angusta) are the two most prominent examples of thermotolerant yeasts and both have beneficial traits besides their thermotolerance. K. marxianus can grow at staggering growth rates and produces ethanol if cultivated at temperatures above 40 °C [13]. O. polymorpha is methylotrophic and exhibits desirably low levels of hyperglycosylation [13, 14]. Conversion of xylose to ethanol at elevated temperatures has also been reported [15].

The relationships of these taxa are shown in Fig. 1, contextualized with prominent yeast evolution events [19].

Phylogenetic tree of thermotolerant yeast and related species. The relationships were inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method [16]. The tree is drawn to scale based on evolutionary distances, which were calculated with MEGA7 [17] using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method [18] based on 26S ribosomal RNA sequences

Both species seem to have surpassed their non-conventional status and have been successfully targeted with novel metabolic engineering tools [20,21,22,23,24]. However, the mechanisms enabling thermotolerance remain unclear and no quantitative physiology data including information on intracellular fluxes is available for growth at elevated temperatures. The aim of this study was to provide this missing data and explore trends in the metabolic network responses of the most prominent thermotolerant yeasts.

Results

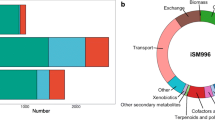

Available literature on thermotolerant yeasts clearly suggests that K. marxianus and O. polymorpha perform well at high temperatures [13, 25]. This was further supported by an initial screening of strains from an internal strain collection (data not shown). To obtain a comprehensive overview on physiology and flux distributions at elevated temperatures and to also explore differences between those two species, three strains of each of the two species were examined at temperatures ranging from 30 to 49 °C. Each of these experiments yielded a comprehensive physiological data set from which specific growth rates, substrate consumption and metabolite secretion rates were calculated. The physiological data sets of three growth experiments are exemplarily shown in Fig. 2); the entirety of calculated physiological data from the shake-flask batch cultures is summarized in Fig. 3. Secretion rates of acetate and glycerol were marginal in all experiments and are not shown here but are presented in the Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Experimental data, generated in minimal medium batch cultivations, and corresponding non-linear fits with (left column) - K. marxianus CBS 2080 at 40 °C, (middle column) – K. marxianus ATCC 748 at 47 °C, and (right column) – O. polymorpha KCTC 17233 at 47 °C. Equivalent data sets were generated for six strains in total and at temperatures varying from 30 °C to 49 °C. The physiological rates calculated from these data sets are condensed in Fig. 3 and furthermore given in more detail in Additional file 2: Tables S1 and S2

Physiological data of O. polymorpha strains (left hand side) and K. marxianus strains (right hand side) from batch experiments on glucose at different temperatures. Depending on the strain, the cultivation temperature was varied between 30 °C and 49 °C in independent experiments. To better illustrate the adaptive responses, the extracellular rates were accentuated with a line corresponding to a fitted spline curve generated from the measured data. The data of O. polymorpha CLIB 421 at 40 °C are taken from Lehnen et al. [26]. μ – specific growth rate

The Ogataea strains showed a phenotype that was highly stable over the investigated range of temperatures, especially up to 40 °C, with growth rates narrowing around 0.4 1/h, glucose uptake rates of 4 mmol/gCDW/h, and oxygen uptake rates of around 8 mmol/gCDW/h. No glycerol production was observed, and significant amounts of acetate were produced only by O. polymorpha KCTC 17233 at 37 °C and 40 °C. O. polymorpha KCTC 17233 was furthermore unique in having a maximum growth rate at 47 °C, while all other strains showed a maximum growth rate at 40 °C. Although O. polymorpha KCTC 17233 was still able to grow at 49 °C, this dataset is excluded here because growth was not exponential. The data of O. polymorpha CLIB 421 at 40 °C has been used in a previous study to validate a 13C-based metabolic flux analysis model [26] and is included here to complement the strain’s fluxome and physiological data at higher temperatures. This strain showed a similar physiological behavior as O. polymorpha NCYC 495 but did not produce any byproducts at the tested temperatures. As an example of the common Ogataea phenotype, a comprehensive flux map of O. polymorpha KCTC 17233 at 47 °C is given in Fig. 5.

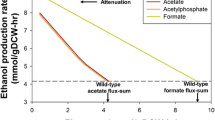

In contrast to the phenotypic stability of the Ogataea strains, the Kluyveromyces strains were highly adaptive to temperature changes exhibiting a variety of phenotypes with large differences also between the individual strains. Two outstanding phenotypes, one defined by a very high growth rate and a second, defined by a high ethanol yield, have already been subject of extensive research [13, 27] and were observed in K. marxianus strains at 40 °C and 47 °C, respectively. Two strains, specifically K. marxianus CBS 712 and K. marxianus ATCC 748, showed growth rates above 0.9 1/h at 40 °C, which is approximately double the maximal growth rate reported for S. cerevisiae [28]. These maximum growth rates were accompanied by high glucose (up to 12 mmol/gCDW/h) and oxygen uptake rates (40 mmol/gCDW/h), and TCA cycle rates reaching 9.5 mmol/gCDW/h (Figs. 3 and 4). Astonishingly, these high growth rates were achieved without compromising the biomass yield, which was maintained above 0.5 gCDW/gglucose. At even higher temperatures, two of the K. marxianus strains produced ethanol reaching production rates as high as 14 mmol/gCDW/h in K. marxianus ATCC 748 at 47 °C. The entire collection of the obtained physiological data is given in the Additional file 2: Tables S1 and S2.

Excerpt of metabolic network responses of O. polymorpha strains (left hand side) and K. marxianus strains (right hand side) in glycolysis (represented by the the phosphoglucose isomerase reaction), the pentose phosphate pathway (represented by the glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase reaction), the tricarboxylic acid cycle (represented by the citrate synthase reaction), and malic enzyme activity to cultivation at higher temperatures. The malic enzyme fluxes producing NADH and NADPH were combined in this representation. Flux values are normalized to the glucose uptake rate. To better illustrate adaptive responses, the fluxes are accentuated with a spline curve fitted to the computed flux data. The reactions are designated by the stoichiometric reaction equation as defined in the model. G6P – glucose-6-phosphate; F6P – fructose-6-phosphate; 6PG – 6-phosphogluconate; ACCOA – acetyl-CoA; OAA – oxaloacetate CIT – citrate; MAL – malate; PYR – pyruvate; mit –mitochondrial localization

To get a better insight into how intracellular flux changes contribute to the observed phenotypic changes, we conducted 13C-metabolic flux analyses (13C-MFA) for all strains and for all temperatures. Both genera showed distinctive flux distributions characterized by a very high pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) flux in the Ogataea strains and comparably higher glycolytic and TCA cycle fluxes for Kluyveromyces. Compared with the Crabtree-positive yeast S. cerevisiae at 30 °C under otherwise identical culture conditions, these oxidative metabolic schemes sustained much higher rates of redox cofactor reduction in all experiments (Figs. 4 and 5) [26].

Simulated flux distributions of (a) - K. marxianus CBS 2080 during growth at 40 °C, (b) – K. marxianus ATCC 748 during growth at 47 °C, and (c) – O. polymorpha KCTC 17233 during growth at 47 °C. The boxed numbers next to the reaction arrows represent the flux values, which were normalized to the glucose uptake rate. Arrow thickness was scaled to the flux value for enhanced visualization. Metabolite abbreviations are defined in the Additional file 3: Flux solutions & sensitivity

To simulate the flux distributions of O. polymorpha NCYC 495 above 40 °C, an additional NADPH consuming flux had to be allowed to generate flux solutions, which were statistically acceptable as checked by a χ2 test. For the datasets generated at temperatures of 45 °C and above this relaxation of the NADPH balance resulted in flux solutions with a partially cyclic PPP activity, i.e., relative PPP fluxes above 1 mol/molglucose.

Not surprisingly, the TCA cycle activity of the investigated Crabtree-negative yeasts was considerably higher in all strains and at all investigated temperatures compared to S. cerevisiae under standard growth conditions with a high of 80% (mol/molglucose) [26, 29]. However, at temperatures above 40 °C, the TCA cycle activity showed a stark decrease accompanied with ethanol formation in two of the Kluyveromyces strains (Fig. 3), while such a metabolic change was not observed with any of the tested O. polymorpha strains.

An excerpt of the flux distribution data of all investigated strains is presented in Fig. 4 focusing on important central metabolic reactions. A collection of all generated flux distribution data and flux maps is given in Additional file 3: Flux solutions & sensitivity.

Discussion

The most notable difference in the metabolic response of Ogataea and Kluyveromyces strains to increased cultivation temperature was the remarkable metabolic variability of Kluyveromyces strains, which is absent in Ogataea. Special focus of the discussion around the metabolic basis of thermotolerance lies on the activity of the PPP, which was increased in all investigated strains compared to S. cerevisiae [28], but it still clustered on distinct levels in the different species. The divergence of metabolic responses becomes readily apparent from the observed secretion rates of metabolites. While the secretion of glycerol, acetate, and ethanol increases in correlation with temperature in S. cerevisiae [30], such a correlation was not observed for the thermotolerant species. Although cells may profit from the thermoprotective property of glycerol [30], none of it was produced by Ogataea and no correlation with temperature was found for Kluyveromyces. Secretion of pyruvate, as described by Fonseca et al. [31] for a different K. marxianus strain and during growth on higher sugar concentrations, was not observed in the present study. This indicates that the response to increased temperature is not conserved among thermotolerant yeast species, much less among yeasts in general.

In the Kluyveromyces strains, the temperature increase resulted in a stark increase of metabolic activities, thereby being in accordance with the temperature dependence of reaction rates described by Arrhenius. The optimal temperature of all three Kluyveromyces strains was around 40 °C at which they showed approximately doubled glucose uptake and growth rates compared to growth at 30 °C. Apparently, at mesophilic temperatures, the strain is not exploiting its maximal metabolic capacity. Additionally, we observed an up to 2-fold increase of the TCA cycle activity indicating that the elevated temperatures cause a typical metabolic stress response. Specifically, the cells experience an increased mitochondrial membrane permeability, concomitant proton influx, protein damage, and lipid peroxidation, which needs to be counteracted by ATPase activity and cell repair mechanisms [32]. These mechanisms explain an increased ATP demand and observed high flux through the TCA cycle [33], climaxing at 40 °C in Kluyveromyces (Fig. 3). At temperatures beyond 40 °C, the collapse of the oxygen uptake rate (Fig. 3) and the TCA cycle activity (Fig. 4) indicates that the damage to the mitochondrial membranes reaches a level that can no longer support respiratory metabolism as previously discussed by M Zhang, J Shi and L Jiang [34]. Alternatively, K. marxianus might actively downregulate the genes of the respiratory chain as has been observed for another strain of this species [35] and discussed as a means to reduce the formation of reactive oxygen species. Both mechanism can explain the onset of fermentative metabolism, apparent from the production of ethanol and acetate.

In contrast to Kluyveromyces, no drastic metabolic shifts, but relatively moderate changes in the flux distributions in Ogataea strains were observed in accordance with the relatively stable phenotype. Of the three tested strains, only O. polymorpha NCYC 495 showed a drop in the glycolytic flux for growth at or above 45 °C and an associated increase in PPP and TCA cycle activity. This might be an indication that thermotolerance in Ogataea is mainly governed by structural predisposition, for example membrane composition that allows for higher stability, or protective mechanisms like glutathione reductase.

One common trait in all flux distributions was the elevated PPP activity compared with S. cerevisiae grown at 30 °C and under standard cultivation conditions. This might be correlated to the high NADPH demand under increased temperatures for glutathione reductase-mediated protection against oxidative stress [36,37,38]. The rerouting of metabolic flux from glycolysis to PPP is reported to be a conserved response to oxidative stress [39] and has also been observed in S. cerevisiae [30, 40]. Ogataea flux distributions were further characterized by a high PPP flux even at moderate temperatures. In this methylotrophic yeast, high PPP activity may also be an inherent characteristic as several PPP associated enzymes are involved in the pathway for methanol assimilation [41]. A cyclic mode of the PPP, as simulated for O. polymorpha NCYC 495 above 40 °C, has recently been discussed as a means to sustain increased NADPH demands [42]. The corresponding, massive increase of excess NADPH production further supports glutathione mediated thermotolerance of this strain [37, 38]. Likewise, cyclic operation of the Entner-Doudoroff pathway has been determined for obligate aerobic bacteria, which might face an increased NADPH demand due to reactive oxygen species and other environmental stresses [43,44,45].

However, a higher potential for glutathione mediated protection against oxidative stress as it results from higher NADPH production is not sufficient for thermotolerance. While it is known that S. cerevisiae, too, is capable of achieving very high PPP activities [40, 46], this strain is not capable of growing at elevated temperatures and has been shown by Blank and Sauer [28] to maintain a low PPP activity in batch at 37 °C [28]. The high PPP activity reported for thermosensitive P. pastoris [47] and K. lactis [48] further support this hypothesis. Hence, structural specialties of the membranes and enzymes of thermotolerant yeasts seem to be more important conditions for metabolic activity at high temperatures [49, 50].

From an applied perspective, the generated quantitative data is valuable for strain and process development purposes as it demonstrates how temperature modulates metabolic fluxes and can be used to explore and tune desirable phenotypes. The presented, comprehensive overview of phenotypes and flux distributions of several interesting Kluyveromyces and Ogataea strains forms a foundation for a reasonable choice of a suitable production host with desirable properties. For example, strains with high PPP activities have an industrial potential for the production of aromatic compounds, relying on the PPP intermediate erythrose-4-phosphate [51]. In K. marxianus, this positive trait is further enhanced by its fast growth rate of 0.94 h− 1 and the simultaneous high biomass yield of 0.5 gCDW/gglucose. Temperature-insensitive physiology, another central result of this study, is highly desirable to confer robustness towards temperature gradients often encountered in large-scale and solid-state fermentations [52, 53].

Conclusion

The generated physiology and fluxome data suggests that there are no highly conserved metabolic traits among thermotolerant yeasts. While the physiological changes and observed metabolic shifts indicate a response to several of the most prominent effects of high temperature and concomitant stresses, like loss of membrane integrity and protective action against reactive oxygen species [34], the response behavior of the various strains varied significantly. When compared to the metabolic fluxes of S. cerevisiae, both analyzed species show increased PPP and TCA cycle activity under all temperature conditions, paired with high biomass yields even at very high growth rates. These quantitative physiological and fluxome data underpin the potential of these two species for biomanufacturing purposes.

Materials and methods

Strains and culture conditions

The strains used in this study were Kluyveromyces marxianus ATCC 748, Kluyveromyces marxianus CBS 2080, Kluyveromyces marxianus CBS 712, Ogataea polymorpha CLIB 421, Ogataea polymorpha NCYC 495, and Ogataea polymorpha KCTC 17233. To produce high quality flux distributions, physiological data, which was used to constrain the flux estimations, and samples of 13C-labeled biomass were obtained from growth experiments, executed according to a standard protocol, only changing strain or temperature between experiments. Cultivations were performed in 1.3 L shake flasks, equipped with O2- and CO2-sensors (BlueSens gas sensor GmbH, Herten, Germany). The flasks were filled with 50 mL of Verduyn medium [54], and shaken at 130 rpm with an amplitude of 30 mm as described in Lehnen et al. [26]. The closed shake flask was equipped with an air-tight sample port. The medium contained per liter 5 g (NH4)2SO4, 3 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g MgSO4∙7H2O, 4.5 mg ZnSO4∙7H2O, 0.3 mg CoCl2∙6H2O, 1.0 mg MnCl2∙4H2O, 0.3 mg CuSO4∙5H2O, 4.5 mg CaCl2∙2H2O, 3.0 mg FeSO4∙7H2O, 0.4 mg NaMoO4∙2H2O, 1.0 mg H3BO3, 0.1 g KI, 15 mg EDTA, 0.05 mg biotin, 1.0 mg calcium pantothenate, 1.0 mg nicotinic acid, 25 mg inositol, 1.0 mg pyridoxine, 0.2 mg p-aminobenzoic acid, 1.0 mg thiamine. The medium was supplemented with 5 g/L glucose consisting of 80% (n/n) 1-13C-glucose and 20% (n/n) U-13C-glucose (both purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany, with 99 atom-% purity), because it allows the determination of intracellular fluxes with good resolution at reasonable costs per experiment [7]. Precultures were grown in the same minimal medium but supplemented with naturally labeled glucose. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed with 0.9% NaCl solution, and used to inoculate the main cultures to a starting optical density (OD600) of 0.05. Biomass samples for determination of the 13C-labeling of proteinogenic amino acids by GC-MS analysis were taken during the exponential growth phase no earlier than five generations after inoculation.

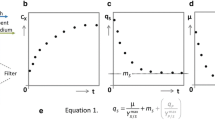

Physiological data acquisition and processing

During the exponential growth phase, samples were taken via the sample port to not disturb the gas composition in the head space as described by Lehnen et al. [26]. The OD600 was measured immediately after sampling. The samples were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 5 min in a Thermo Scientific Heraeus Pico 17 tabletop centrifuge. The biomass pellet and the supernatant were stored separately at − 20 °C until further analysis. The pellet was used for GC-MS analysis of proteinogenic amino acids (see below). The concentrations of glucose and the excreted metabolites ethanol, glycerol, and acetate were determined by HPLC analysis of the supernatant. A constant flow of 0.8 mL/min of 5 mM H2SO4 was used to separate the metabolites on an Aminex HPX-87H column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 60 °C. Glucose, ethanol, and glycerol were quantified with a Shodex RI-101 detector, and a variable wavelength detector of an UltiMate 3000 HPLC system (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was used at 210 nm to quantify acetate. The cell dry weight (CDW) of samples was calculated from the measured OD600 and calibration curves, which were specific for the experimental conditions. The off-gas analysis system provided by BlueSens gas sensor GmbH (Herten, Germany) and included BCP-O2 and BCP-CO2 sensors connected to a BACCom12 communication box to obtain signlas in units Vol-% using the FermVis software. These signlas were transformed into molar concentrations as described by J Heyland, J Fu and LM Blank [29]. Exponential growth rate, substrate uptake rates, and metabolite secretion rates were calculated by a simultaneous nonlinear fit of the time-dependent concentration changes, using SigmaPlot Version 12.5 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) and the CO2 production rate was corrected for the insensitivity of the sensors towards labeled CO2, as described by M Lehnen, BE Ebert and LM Blank [26].

13C-labeling analysis

13C-labeling patterns of proteinogenic amino acids were determined from biomass samples taken in the mid-exponential growth phase. Approximately 0.3 mg of biomass was hydrolyzed at 105 °C for 6 h after resuspension of the pellet in 6 M HCl and then dried overnight at 80 °C. Derivatization of the dried hydrolysate was done in a mix of 30 μL acetonitrile and 30 μL N-methyl-N-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-trifluoroacetamide (CS-Chromatographie Service GmbH, Langerwehe, Germany) for one our at 85 °C for 1 h to allow derivatization. The derivatized samples were analyzed on a gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) triple quadrupole system. The GC-MS system consisted of a TRACE™ GC Ultra and a TSQ triple quadrupole MS with electron impact ionization (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a TraceGOLD TG-5SilMS fused silica column (length, 15 m; inner diameter, 0.25 mm; film thickness, 0.25 μm) and was operated as described by Schmitz et al. [55]. Helium was used as carrier gas at a constant gas flow rate of 1 mL/min and at a split ratio of 1:15. The injector temperature was set to 270 °C, and the column oven was heated according to a ramped program. The initial temperature of 140 °C was held for 1 min, the temperature was then increased with a rate of 10 °C/min to a final value of 310 °C, which was held time for 1 min. iMS2Flux [56] was used to correct the raw GC-MS data for unlabeled biomass, introduced with the inoculum, and the natural abundance of heavy isotopes and to transform the corrected data into mass distribution vectors.

13C-MFA method and model constraints

To compute the intracellular fluxes, OpenFLUX was used [5, 57], based on a model that described the central carbon metabolism compartmented into cytosol and mitochondria [26] and included glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, with approximately 50 reactions. Biomass production was linked to twelve intermediates of this central network [58]. The model was constrained with experimentally determined uptake and secretion rates, precursor drains into biomass, and compartmental localization of amino acid biosynthesis. As shown by M Lehnen, BE Ebert and LM Blank [26], it is most effective to constrain amino acid biosynthesis only for those amino acids where pathway localization information is unambiguous and to allow parallel biosynthesis in both compartments for all other amino acids. Based on the genome sequence of O. polymorpha NCYC 495, available from the homepage of the Joint Genome Institute (JGI) (http://genome.jgi.doe.gov/Hanpo2/Hanpo2.home.html, accessed in April 2016) and the genome sequence of K. marxianus KCTC 17555, which is deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession number AKFM00000000 [59], pathway localizations where computationally predicted using TARGETP 1.1 [60] and WoLF PSORT [61] for all strains as discussed in [62]. Detailed information on model constraints applied to evaluate the Ogataea and Kluyveromyces datasets, respectively, is given in the supplement.

Abbreviations

- CDW:

-

Cell dry weight

- GC-MS:

-

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- MFA:

-

Metabolic flux analysis

- PPP:

-

Pentose phosphate pathway

- TCA:

-

Tricarboxylic acid

References

Pscheidt B, Glieder A. Yeast cell factories for fine chemical and API production. Microb Cell Factories. 2008;7:25.

Liu L, Redden H, Alper HS. Frontiers of yeast metabolic engineering: diversifying beyond ethanol and Saccharomyces. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24(6):1023–30.

Toya Y, Shimizu H. Flux analysis and metabolomics for systematic metabolic engineering of microorganisms. Biotechnol Adv. 2013;31(6):818–26.

Stephanopoulos G. Metabolic fluxes and metabolic engineering. Metab Eng. 1999;1(1):1–11.

Quek L-E, Nielsen LK: Steady-state 13C fluxomics using OpenFLUX. In: Metabolic flux analysis: methods and protocols. Edited by Krömer JO, Nielsen LK, Blank LM. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2014: 209–224.

Weitzel M, Noh K, Dalman T, Niedenfuhr S, Stute B, Wiechert W. 13CFLUX2 - high-performance software suite for 13C-metabolic flux analysis. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(1):143–5.

Zamboni N, Fendt S-M, Ruhl M, Sauer U. 13C-based metabolic flux analysis. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(6):878–92.

Shi DJ, Wang CL, Wang KM. Genome shuffling to improve thermotolerance, ethanol tolerance and ethanol productivity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;36(1):139–47.

Caspeta L, Nielsen J. Thermotolerant yeast strains adapted by laboratory evolution show trade-off at ancestral temperatures and preadaptation to other stresses. Mbio. 2015;6:4.

Shin KS, Shin YK, Yoon JH, Park YH. Candida thermophila sp. nov., a novel thermophilic yeast isolated from soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001;51(Pt 6:2167–70.

Banat IM, Nigam P, Marchant R. Isolation of thermotolerant, fermentative yeasts growing at 52°C and producing ethanol at 45°C and 50°C. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 1992;8(3):259–63.

Radecka D, Mukherjee V, Mateo RQ, Stojiljkovic M, Foulquie-Moreno MR, Thevelein JM: Looking beyond Saccharomyces: the potential of non-conventional yeast species for desirable traits in bioethanol fermentation. FEMS Yeast Res 2015, 15(6):fov053-fov053.

Lane MM, Burke N, Karreman R, Wolfe KH, O'Byrne CP, Morrissey JP. Physiological and metabolic diversity in the yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2011;100(4):507–19.

van Dijk R, Faber KN, Kiel JA, Veenhuis M, van der Klei I. The methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha: a versatile cell factory. Enzym Microb Technol. 2000;26(9–10):793–800.

Ryabova OB, Chmil OM, Sibirny AA. Xylose and cellobiose fermentation to ethanol by the thermotolerant methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha. FEMS Yeast Res. 2003;4(2):157–64.

Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4(4):406–25.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–4.

Tamura K, Nei M, Kumar S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(30):11030–5.

Dujon B, Sherman D, Fischer G, Durrens P, Casaregola S, Lafontaine I, De Montigny J, Marck C, Neuveglise C, Talla E, et al. Genome evolution in yeasts. Nature. 2004;430(6995):35–44.

Lobs AK, Engel R, Schwartz C, Flores A, Wheeldon I. CRISPR-Cas9-enabled genetic disruptions for understanding ethanol and ethyl acetate biosynthesis in Kluyveromyces marxianus. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10(1):164.

Fonseca GG, de Carvalho NM, Gombert AK. Growth of the yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus CBS 6556 on different sugar combinations as sole carbon and energy source. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(11):5055–67.

Gombert AK, Madeira JV Jr, Cerdan ME, Gonzalez-Siso MI. Kluyveromyces marxianus as a host for heterologous protein synthesis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100(14):6193–208.

Saraya R, Gidijala L, Veenhuis M, van der Klei IJ: Tools for genetic engineering of the yeast Hansenula polymorpha. In: Yeast metabolic engineering: methods and protocols. Edited by Mapelli V. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2014: 43–62.

Kata I, Semkiv MV, Ruchala J, Dmytruk KV, Sibirny AA. Overexpression of the genes PDC1 and ADH1 activates glycerol conversion to ethanol in the thermotolerant yeast Ogataea (Hansenula) polymorpha. Yeast. 2016;33(8):471–8.

Cabecasilva C, Madeiralopes A. Temperature relations of yield, growth and thermal death in the yeast Hansenula polymorpha. Z Allg Mikrobiol. 1984;24(2):129–32.

Lehnen M, Ebert BE, Blank LM. A comprehensive evaluation of constraining amino acid biosynthesis in compartmented models for metabolic flux analysis. Metab Eng Commun. 2017;5:34–44.

Nonklang S, Abdel-Banat BM, Cha-aim K, Moonjai N, Hoshida H, Limtong S, Yamada M, Akada R. High-temperature ethanol fermentation and transformation with linear DNA in the thermotolerant yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus DMKU3-1042. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(24):7514–21.

Blank LM, Sauer U. TCA cycle activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a function of the environmentally determined specific growth and glucose uptake rates. Microbiology. 2004;150(4):1085–93.

Heyland J, Fu J, Blank LM. Correlation between TCA cycle flux and glucose uptake rate during respiro-fermentative growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology. 2009;155(Pt 12:3827–37.

Woo JM, Yang KM, Kim SU, Blank LM, Park JB. High temperature stimulates acetic acid accumulation and enhances the growth inhibition and ethanol production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae under fermenting conditions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(13):6085–94.

Fonseca GG, Gombert AK, Heinzle E, Wittmann C. Physiology of the yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus during batch and chemostat cultures with glucose as the sole carbon source. FEMS Yeast Res. 2007;7(3):422–35.

Piper PW. Molecular events associated with acquisition of heat tolerance by the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;11(4):339–55.

Gao L, Liu Y, Sun H, Li C, Zhao Z, Liu G. Advances in mechanisms and modifications for rendering yeast thermotolerance. J Biosci Bioeng. 2016;121(6):599–606.

Zhang M, Shi J, Jiang L. Modulation of mitochondrial membrane integrity and ROS formation by high temperature in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Electron J Biotechnol. 2015;18(3):202–9.

Lertwattanasakul N, Kosaka T, Hosoyama A, Suzuki Y, Rodrussamee N, Matsutani M, Murata M, Fujimoto N, Suprayogi TK, et al. Genetic basis of the highly efficient yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus: complete genome sequence and transcriptome analyses. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2015;8:47.

Konings AWT: Importance of the glutathione level and the activity of the pentose phosphate pathway in cellular heat sensitivity. In: Preclinical Hyperthermia. Edited by Hinkelbein W, Bruggmoser G, Engelhardt R, Wannenmacher M. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 1988: 109–125.

Grant CM. Role of the glutathione/glutaredoxin and thioredoxin systems in yeast growth and response to stress conditions. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39(3):533–41.

Sugiyama K, Izawa S, Inoue Y. The Yap1p-dependent induction of glutathione synthesis in heat shock response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(20):15535–40.

Morano KA, Grant CM, Moye-Rowley WS. The response to heat shock and oxidative stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2012;190(4):1157–95.

Celton M, Sanchez I, Goelzer A, Fromion V, Camarasa C, Dequin S. A comparative transcriptomic, fluxomic and metabolomic analysis of the response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to increases in NADPH oxidation. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:317.

Yurimoto H, Oku M, Sakai Y. Yeast methylotrophy: metabolism, gene regulation and peroxisome homeostasis. Int J Microbiol. 2011;2011:101298.

Rui B, Yi Y, Shen T, Zheng M, Zhou W, Du H, Fan Y, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Xu S, et al. Elementary flux mode analysis revealed cyclization pathway as a powerful way for NADPH regeneration of central carbon metabolism. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129837.

Nikel PI, Chavarria M, Fuhrer T, Sauer U, de Lorenzo V. Pseudomonas putida KT2440 strain metabolizes glucose through a cycle formed by enzymes of the Entner-Doudoroff, Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas, and pentose phosphate pathways. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(43):25920–32.

Lien SK, Niedenfuhr S, Sletta H, Noh K, Bruheim P. Fluxome study of Pseudomonas fluorescens reveals major reorganisation of carbon flux through central metabolic pathways in response to inactivation of the anti-sigma factor MucA. BMC Syst Biol. 2015;9:6.

Hanke T, Noh K, Noack S, Polen T, Bringer S, Sahm H, Wiechert W, Bott M. Combined fluxomics and transcriptomics analysis of glucose catabolism via a partially cyclic pentose phosphate pathway in Gluconobacter oxydans 621H. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79(7):2336–48.

Frick O, Wittmann C. Characterization of the metabolic shift between oxidative and fermentative growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by comparative 13C flux analysis. Microb Cell Factories. 2005;4(1):30.

Jorda J, Rojas HC, Carnicer M, Wahl A, Ferrer P, Albiol J. Quantitative metabolomics and instationary 13C-metabolic flux analysis reveals impact of recombinant protein production on trehalose and energy metabolism in Pichia pastoris. Metabolites. 2014;4(2):281–99.

Tarrio N, Becerra M, Cerdan ME, Gonzalez Siso MI. Reoxidation of cytosolic NADPH in Kluyveromyces lactis. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6(3):371–80.

Mejia-Barajas J, Montoya-Perez R, Manzo-Avalos S, Cortes-Rojo C, Riveros-Rosas H, Cervantes C, Saavedra-Molina A. Fatty acid addition and thermotolerance of Kluyveromyces marxianus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2018;365:7.

Fields PA. Review: protein function at thermal extremes: balancing stability and flexibility. Comp Biochem Phys A. 2001;129(2–3):417–31.

Kromer JO, Nunez-Bernal D, Averesch NJ, Hampe J, Varela J, Varela C. Production of aromatics in Saccharomyces cerevisiae--a feasibility study. J Biotechnol. 2013;163(2):184–93.

Mitchell DA, Krieger N, Stuart DM, Pandey A. New developments in solid-state fermentation II. Rational approaches to the design, operation and scale-up of bioreactors. Process Biochem. 2000;35(10):1211–25.

Bück A, Casciatori FP, Thomeo JC, Tsotsas E. Model-based control of enzyme yield in solid-state fermentation. Procedia Engineer. 2015;102:362–71.

Verduyn C, Postma E, Scheffers WA, Van Dijken JP. Effect of benzoic acid on metabolic fluxes in yeasts: a continuous-culture study on the regulation of respiration and alcoholic fermentation. Yeast. 1992;8(7):501–17.

Schmitz A, Ebert BE, Blank LM. GC-MS-based determination of mass isotopomer distributions for 13C-based metabolic flux analysis. In: Hydrocarbon and lipid microbiology protocols: genetic, genomic and system analyses of pure cultures; 2017. p. 223–43.

Poskar CH, Huege J, Krach C, Franke M, Shachar-Hill Y, Junker BH. iMS2Flux - a high-throughput processing tool for stable isotope labeled mass spectrometric data used for metabolic flux analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13(1):295.

Quek LE, Wittmann C, Nielsen LK, Kromer JO: OpenFLUX: efficient modelling software for 13C-based metabolic flux analysis. In: Microb Cell Fact. vol. 8, 2009/05/05 edn; 2009: 25.

Christen S, Sauer U. Intracellular characterization of aerobic glucose metabolism in seven yeast species by 13C flux analysis and metabolomics. FEMS Yeast Res. 2011;11(3):263–72.

Jeong H, Lee DH, Kim SH, Kim HJ, Lee K, Song JY, Kim BK, Sung BH, Park JC, Sohn JH, et al. Genome sequence of the thermotolerant yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus var. marxianus KCTC 17555. Eukaryot Cell. 2012;11(12):1584–5.

Emanuelsson O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(4):953–71.

Horton P, Park KJ, Obayashi T, Fujita N, Harada H, Adams-Collier CJ, Nakai K. WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Web Server issue:W585–7.

Forster J, Halbfeld C, Zimmermann M, Blank LM. A blueprint of the amino acid biosynthesis network of hemiascomycetes. FEMS Yeast Res. 2014;14(7):1090–100.

Acknowledgements

Holger Müller from BlueSens is acknowledged for his support with off-gas analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and the Biotechnology Research and Information Network AG (BRAIN AG) as part of the Strategic Alliance Zero Carbon Footprint (Grant No. FKZ 031A217F). The GC-MS/MS was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG; Grant No. INST 2221018–1 FUGG). The funders had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Declarations

All data are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ML, BEE, and LMB conceived and designed the study and evaluated the data. ML performed all experiments and analyses. ML and BEE wrote the manuscript; LMB edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Supplementary physiological data of K. marxianus strains and O. polymorpha strains from batch experiments on glucose at different temperatures. Figures S2-S25. Flux maps of all strains for all tested temperatures. (DOCX 6050 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Physiological rates of K. marxianus strains from batch experiments on glucose at different temperatures. Depending on the strain, the cultivation temperature was varied between 30 °C and 49 °C in different experiments. Table S2. Physiological rates of O. polymorpha strains from batch experiments on glucose at different temperatures. Depending on the strain, the cultivation temperature was varied between 30 °C and 49 °C in different experiments. (DOCX 26 kb)

Additional file 3:

Optimal flux solutions for all simulated data sets, including the corresponding smallest sum of residual errors (fval) and the constraints for uptake and production rates of metabolites and biomass constituents, which were used in the simulations. (XLSX 516 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lehnen, M., Ebert, B.E. & Blank, L.M. Elevated temperatures do not trigger a conserved metabolic network response among thermotolerant yeasts. BMC Microbiol 19, 100 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-019-1453-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-019-1453-3