Abstract

Background

A deeply rooted phylogenetic lineage of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) termed lineage 7 was discovered in Ethiopia. Whole genome sequencing of 30 lineage 7 strains from patients in Ethiopia was performed. Intra-lineage genome variation was defined and unique characteristics identified with a focus on genes involved in DNA repair, recombination and replication (3R genes).

Results

More than 800 mutations specific to M. tuberculosis lineage 7 strains were identified. The proportion of non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (nsSNPs) in 3R genes was higher after the recent expansion of M. tuberculosis lineage 7 strain started. The proportion of nsSNPs in genes involved in inorganic ion transport and metabolism was significantly higher before the expansion began. A total of 22346 bp deletions were observed. Lineage 7 strains also exhibited a high number of mutations in genes involved in carbohydrate transport and metabolism, transcription, energy production and conversion.

Conclusions

We have identified unique genomic signatures of the lineage 7 strains. The high frequency of nsSNP in 3R genes after the phylogenetic expansion may have contributed to recent variability and adaptation. The abundance of mutations in genes involved in inorganic ion transport and metabolism before the expansion period may indicate an adaptive response of lineage 7 strains to enable survival, potentially under environmental stress exposure. As lineage 7 strains originally were phylogenetically deeply rooted, this may indicate fundamental adaptive genomic pathways affecting the fitness of M. tuberculosis as a species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) has been a major cause of morbidity and mortality among humans for millennia. Each year, approximately 9 million people contract TB and 1.5 million die from the disease [1]. TB is caused by bacterial strains belonging to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC). Whole genome sequencing (WGS) analysis classifies MTBC into seven main lineages (lineages 1–7); lineages 2, 3 and 4 belong to the evolutionary modern group and are considered more recently diversified compared to the ancient lineages of 1, 5 and 6 [2]. An improved understanding of the evolutionary constraints and facilitators on natural populations of MTBC strains is required to develop TB control strategies that efficiently consider the dynamics of mycobacterial evolution.

MTBC and the human host have a long-term co-evolutionary relationship. It is presumed that M. tuberculosis originated in Africa and co-evolved into modern lineages with the out-migration of humans from Africa 70–80 thousand years ago [3]. The lineage distribution among cases caused by M. tuberculosis exerts distinct geographical associations worldwide [2, 4]. While lineages 1 and 3 are prevalent in East Africa, Central, South- and South-East Asia, lineages 2 and 4 are the most widely distributed worldwide. Lineages 5 and 6, which are also known as M. africanum West Africa 1 and West Africa 2, respectively, are localized in West Africa [5, 6]. Lineage 7 is a M. tuberculosis lineage recently discovered in north-western Ethiopia and among Ethiopian immigrants in Djibouti [7–10].

We previously investigated the clinical relevance of M. tuberculosis lineage 7 as compared to other lineages and found that lineage 7 is associated with prolonged patient delay and slow growth in vitro [11]. Furthermore, phylogenetic characterization of lineage 7 strains by mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit-variable-number tandem-repeat (MIRU-VNTR) revealed deep phylogenetic branching and recent expansion of this lineage [11]. Factors that may have contributed to the recent expansion are not known. It also remains to be determined which factors may have contributed to growth rate and how this relates to the maintained fitness of lineage 7 strains.

Thirty M. tuberculosis lineage 7 strains were subjected to WGS. The genomic profiles were analyzed, evolution was characterized and potential drivers of the recent phylogenetic expansion were identified. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) specific to lineage 7 strains were specified. We focused specifically on the presence of repair, recombination and replication (3R) gene mutations relative to the timing of pre- and post-expansion, and on mutations that may be associated with the success of slow-growing lineage 7 M. tuberculosis strains.

Methods

Bacterial strains, genotyping and drug susceptibility testing

This study included 30 M. tuberculosis isolates that were cultivated from sputum samples collected from pulmonary TB patients presenting at selected health care facilities in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia during the period 2008–10 as previously described [9, 10]. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics in Eastern Norway (REK Øst) and the Ethiopian Science and Technology Ministry in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Written informed consent was obtained from the study participants before the study was commenced.

Strains defined as lineage 7 were identified by spoligotyping as SIT910 and SIT1724 [9] as previously described [3, 8]. The strains were transferred to Oslo University Hospital, Norway and checked for purity by culturing on Middlebrook 7H10 agar, chocolate agar, and MGIT™ Middlebrook 7H9 in a BACTEC™ 960 (BD, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Drug susceptibility testing (DST) was performed by the proportional absolute concentration [12] and BACTEC™ MGIT™ 960 (BD, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions [13].

DNA isolation and whole genome sequencing

Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (gDNA) was isolated from M. tuberculosis lineage 7 strains grown on Middlebrook 7H10 agar according to standard procedures [14]. Genomic libraries were paired-end sequenced using the MiSeq Gene and Small Genome Sequencer (Illumina, USA) according to the manufacturer’s specifications (GATC Biotech AG, Germany). Samples were prepared to produce a mean fragment size ~300 bp. To optimize downstream analyses, quality control was performed using the Qualimap [15] and FASTQC programs (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Sequence data have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive with the study accession code PRJEB13960.

Bioinformatics analyses

Paired-end lineage 7 genome sequence reads were mapped to the genome sequence of the M. tuberculosis H37Rv reference strain (version NC_000962.3) using BWA aligner [16]. The genome sequence mapping results were visualized according to the WGS of the H37Rv reference strain and its genome annotation using Unipro UGENE. In order to identify SNPs uniquely associated with lineage 7 strains, the sequences were compared with those available from previously sequenced MTBC strains stored on publicly available databases (Additional file 1). Comparative SNP typing was performed on 161 isolates (33 lineage 7 and 128 representative of lineages 1–6) using the Unified Genotyper of the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK). In-house Python modules were applied to all generated Variant Call Format (VCF) files in parallel to comparatively analyse and filter the SNPs detected, and to produce a comparative multiple sequence alignment of all positions for which a SNP was called in at least one of the strains in the complete dataset. SNPs were retained if they were supported by 5 reads with a quality control (QC) score ≥ 30. SNPs in PE/PGRS genes, mobile elements, and those linked to insertion/deletion regions were excluded from the analysis. Indels were mapped by combining BreakDancer [17] and Pindel [18] outputs. All DNA sequence structural variations identified were inspected manually. Genes harbouring nsSNPs or indels were grouped according to the different classes of the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) classification [19, 20]. Deletions were visualised using the matplotlib library.

Phylogeny and evolutionary predictions

Phylogeny was inferred using RaxML (version 8.1.3). RaxML was used for Maximum likelihood (ML) based estimates of the MTBC phylogeny and 1000 bootstrap replicates were performed to assess statistical support. The phylogenetic trees were visualized using FigTree (version 1.4.0). The substitutions leading to each SNP were mapped to the phylogenetic tree using Mesquite version 3.02 using the parsimony ancestral state reconstruction method (Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis, Version 3.02) [21]. Identification of the ML-based common ancestor (MLCA) and the presence of a clock-like signal in this dataset were investigated by plotting the root-to-tip distance against time using a linear regression model using Path-O-Gen software.

Statistical analysis

The binomial test was used to compare the sSNPs vs nsSNPs distribution of COG categories in lineage 7 strains. We took into account the number of SNPs in each category and the total length of the genes where mutations are located. For each cell, the binomial test was calculated using Excel as follows: BINOMIAL DIST (Number of SNPs, Total number of SNPs, gene length/Total gene length, 1).

Results

MTBC lineage 7 strains are originally deeply rooted in the phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree was built based on the complete number of SNPs extracted from genomic DNA sequences as compared to a diverse set of whole genome sequences from 161 MTBC WGS (Fig. 1a). Lineage 7 strains form a distinct group which is positioned deeply between the “ancient” and evolutionary “modern” lineages. Furthermore, lineage 7 strains were shown to exhibit a recent expansion (Fig. 1a). Bayesian statistical methods employed to estimate the time of the primary lineage 7 expansion suggested that it started approximately 310 years ago (Additional file 2).

Lineage 7 strains exhibit a high number of nsSNPs in metabolic genes

A total of 3215 SNPs were observed in lineage 7 when compared to other MTBC lineages (Fig. 1b). The proportions of synonymous SNPs (sSNPs) and non-synonymous SNPs (nsSNPs) distribution in the lineage 7 isolates were compared. sSNPs and nsSNPs accounted for 1140 (35.45 %) and 2075 (64.5 %) events, respectively, with an overall SNP ratio of 1.8. The number of SNPs in intergenic regions was 334.

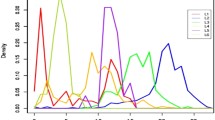

More than 800 SNPs specific to lineage 7 isolates were identified when compared to the WGS of isolates that belong to the different MTBC lineages. The SNP distribution in the lineage 7 strains showed variation as shown in Fig. 2a.

a Distribution of all identified SNPs in lineage 7 strains based on the Cluster of Orthologous Classification (COG). The green color defines the synonymous SNPs and the red color the non-synonymous SNPs. b Similarity matrix based on whole genome analysis. The percentages indicated in each box correspond to the identity between two isolates at the genomic level. Letter codings are described as follows: [C] Energy production and conversion, [D] Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning, [E] Amino acid transport and metabolism, [F] Nucleotide transport and metabolism, [G] Carbohydrate transport and metabolism, [H] Coenzyme transport and metabolism, [I] Lipid transport and metabolism, [K] Transcription, [L] Replication, recombination and repair, [M] Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis, [N] Cell motility, [O] Post-translational modification, protein turnover, and chaperones, [Q] Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism, [T] Signal transduction mechanisms, [U] Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport, [V] Defense mechanisms

We analyzed the distribution of the total 3215 SNPS observed in lineage 7. Accordingly, 1974 SNPs were located in the genomic coding regions that were classified in the following cluster of orthologous gene (COG) categories: secondary metabolite biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism (Q) (n = 280); energy production and conversion (C) (n = 205); lipid transport and metabolism (I) (n = 185); amino acid transport and metabolism (E) (n = 170); transcription (K) (n = 154); signal transduction mechanisms (T) (n = 143); inorganic ion transport and metabolism (P) (n = 132); replication, recombination, and repair (L) (n 126); coenzyme transport and metabolism (H) (n =125); carbohydrate transport and metabolism (G) (n = 116); cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis (M) (n = 109); posttranslational modification, protein turnover, and chaperones (O) (n = 72); cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning (D) (n = 52); nucleotide transport and metabolism (F) (n = 50); defense mechanisms (V) (n = 43); intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport (U) (n =12) (Fig. 2b and Table 1).

Lineage 7 strains exhibited a high proportion of mutations inducing an amino acid change in genes involved in carbohydrate transport and metabolism, energy production and conversion, defense mechanisms, secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism, inorganic ion transport and metabolism, and post-translational modification, protein turnover, and chaperone. In contrast, a low frequency of mutation was observed in genes involved in nucleotide transport and metabolism, intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport, and cell motility (Fig. 2b and Table 1).

To elucidate drivers of recent lineage 7 expansion, mutations in major COG categories before and after the phylogenetic expansion period were compared. Accordingly, the number of nsSNPs in 3R genes (COG category L) were significantly higher after than before the expansion started (nsSNP/sSNP ratios of 2.3 and 1.2, respectively, P-value < 0.05, χ 2 test) (Fig. 3).

The number of nsSNPs in genes involved in inorganic ion transport and metabolism were significantly higher before than after the expansion began (nsSNP/sSNP ratios of 3.9 and 2.5, respectively, P-value < 0.05, χ 2 test) (Fig. 3). Among the genes involved in inorganic ion transport and metabolism (COG category P), polyphosphate kinase (PPK1) exhibited a high number of nsSNP (Additional file 3). A high number of nsSNPs were also observed in the following genes: dnaB and Rv2090 (3R genes), glpk (gene involved in glycerol metabolism); pks12 and pks8 (genes involved in secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism); mmpl12, mmpl4 and mmpl3 (genes involved in fatty acid transport); and mbtE and accA3 (genes involved in long fatty acid synthesis) (Additional file 3).

Deletion analyses

A total of 22346 bp deletion events occurred along the WGS phylogeny. The specific sites of the deleted genes including their functional categories were: Rv2650c-Rv2659c (insertion sequences and phages); lppO or Rv2290 (cell wall and cell processes); sseB or Rv2291 (intermediary metabolism and respiration); rmlB3 (Rv 3468), mhpE (Rv3669), ilvB2 (Rv 3470) (intermediary metabolism and respiration); Rv2645-Rv2647 (insertion sequences and phages); Rv2645 (unknown functional category); Rv2646 (insertion sequences and phages); and Rv1573-Rv1587(insertion sequences and phages) (Fig. 4).

List of specific deletions identified in all lineage 7 isolates included in this study. Deletions were identified by calculating the coverage rate throughout the genome using bedtools on the alignment files generated by samtools. Each line corresponds to the coverage rate for each strain. The gray line corresponds to a control strain that does not include any of the identified deletions specific for the lineage isolates. For each deletion, the information is: genomic coordinates, size of the deleted region and the genes concerned.

Discussion

This is the first genomic study that provides an insight into the recent evolution and drivers of fitness for survival among M. tuberculosis lineage 7 strains. Genomic phylogenetic tree analysis positioned lineage 7 between “ancient” and “modern” lineages, confirming the findings in previous MIRU-VNTR studies [5, 6]. More than 800 SNPs specific to M. tuberculosis lineage 7 strains were identified, indicating that the bacterium was accumulating specific mutations for a long time before the phylogenetic expansion began.

In contrast to the deeply rooted M. canettii, which grows faster than MTBC strains of other lineages [22], lineage 7 strains grow slowly in vitro [11]. To identify SNPs that potentially could be associated with the expansion event, the proportion of nsSNP and sSNP mutations in functional components according to COG were compared. Mutations in genes involved in inorganic ion transport and metabolism were significantly higher before rather than after the expansion started while mutations in 3R genes were significantly higher after the expansion began. The significant increase of nsSNPs in 3R genes corroborates our previous finding on M. tuberculosis adaptive responses [23–25] and may be related to fitness for survival. This could be a consequence of selected critical mutations induced at a specific time point, presumably at an early stage of the lineage 7 expansion, leading to a transient or constitutive adapted mutator phenotype.

Other factors may also have contributed to the recent expansion. Hosts with reduced immune competence due to poor nutrition could have facilitated lineage 7 strains to evolve rapidly leading to more mutations and hence diversity. In addition, poor living conditions, frequent drought and rapid population growth in the country may have given lineage 7 ample opportunity for diversification.

The significant increase in nsSNP in inorganic ion transport and metabolism before the expansion period may indicate a coping strategy adopted by lineage 7 strains against a potential environmental stress factor to which the bacteria were exposed. M. tuberculosis may encounter a multitude of stress factors (e.g. oxidative, acidic, nutrient, membrane damage, heat shock and ribosomal stress factors) when interacting with the host that potentially induce adaptive responses enabling improved survival [26]. Specifically, the high proportion of nsSNP observed in the polyphosphate kinase 1 (PPK1) gene may indicate possible exposure of lineage 7 strains to stressful environmental conditions. Previous studies showed that the PPK1 gene plays a crucial role in bacterial survival under conditions of stress including lag-phase, under nutrient starvation and oxidative stress [27, 28]. It may be speculated that lineage 7 strains accumulated mutations to adapt to such types of stress before the recent expansion started. An earlier study showed that bacteria without the ability to adapt to oxidative and nitrosative stress grow slowly in macrophages and are likely to die [29]. Additional transcriptomic and proteomic studies are warranted to further investigate the adaptive responses of lineage 7 strains to stress factors that are likely to be associated with the timing of the recent expansion. A significant decrease of nsSNPs in genes involved in inorganic ion transport and metabolism was observed after the recent expansion of lineage 7 started (Fig. 3). Very low levels of nsSNPs have previously been attributed to the effect of purifying selection [30].

A high frequency of nsSNPs mutation in the dnaB gene was observed. A former biochemical study indicated that the dnaB gene plays an important role in both initiation and elongation of DNA helicase [31]. A very high proportion of nsSNPs in the glpk gene, involved in glycerol utilization [6], was also observed. An earlier study identified the glpk gene as one of the 42 growth-attenuating genes in M. tuberculosis [32]. Therefore, the high frequency of mutations observed in this gene may be linked to the slow in vitro growth of lineage 7 strains reported in our previous study [11]. Further investigations into the enzymatic function of these genes are warranted to analyze the effect on in vitro growth of lineage 7 stains.

A number of gene deletions specific to lineage 7 strains were observed. One area of deletion was in the regions of Rv3468-Rv3470. Valine and isoleucine biosynthesis that involve Rv3470 [32] are essential pathways required for optimal growth of the bacteria. The deletion of RV3470 is thus likely to have contributed to the phenotypic consequences of slow in vitro growth among lineage 7 strains [11].

To date, the distribution of the “ancient” M. tuberculosis lineages, 5, 6 and M. canettii is restricted to Africa, now supplemented by lineage 7. It is not known why these three lineages are found only in specific regions of Africa. The ability to cause secondary cases and/or outbreaks is considered to be a measure of fitness or success in MTBC transmission. Given the restricted geographic distribution, “ancient” M. tuberculosis lineages are not as successful as “modern” lineages. Despite the fast-growing nature of M. canettii as compared to other strains, only 60 M. canettii strains have been recognized to date [33]. Ancient lineages are being replaced by modern strains; the prevalence of M. africanum West African 2 in Guinea-Bissau decreased from 51 % to 39 % between 1989 and 2008 [34]. The prevalence of M. africanum lineages in other countries including Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Cameroon is also declining [35–38]. More studies are needed to characterize the transmission pattern of the recently identified M. tuberculosis lineage 7 strains.

Results of a previous study indicated that natural variation among clinical isolates may change epidemiologic patterns in a population [39]. Infection with M. tuberculosis strains that illicit pro-inflammatory cytokines are very well controlled in healthy persons with effective innate responses [39]. In contrast, another study demonstrated that a slower growing M. tuberculosis strain causing a less protective innate immune response may more effectively elicit active disease and increase transmission in the community [40]. Lineage 7 accounted for 16 % of the distribution and was the second largest cluster among the strains collected in our previous study [9]. This shows that lineage 7, despite growing slowly in vitro, is responsible for significant transmission in a heterogeneous community. This may indicate that the fitness of lineage 7 strains results in relatively efficient transmission of TB.

Lineage 7 is prevalent in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia (9). An earlier study by Firdessa et al. [8] reported lineage 7 strains from the Woldiya area of the Amhara Region. Genotyping data from the national prevalence survey in Ethiopia reported two SIT910 lineage 7 strains from East Gojjam Zone of the Amhara Region [41]. Our study included a higher number of lineage 7 strains than any other study to date, which might suggest that the Amhara Region of Ethiopia may be the cradle of M. tuberculosis lineage 7.

Conclusions

TB caused by M. tuberculosis lineage 7 strains is an emerging disease in Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa. Due to the high mobility and migration of people in this region, the presence of ecological and individual risk factors, and the increasing trend of surveillance, it is likely that the number of MTBC lineage 7 cases diagnosed will increase.

This study identified unique genomic signatures associated with MTBC lineage 7 strains and identified SNPs in genes possibly related to the clinical and microbiological features observed. We suggest that the relatively high proportion of nsSNPs in 3R genes may have contributed to the recent phylogenetic expansion of lineage 7 strains that started approximately 310 years ago. The high frequency of mutations in genes involved in inorganic ion transport and metabolism before the expansion period may indicates an adaptive response of lineage 7 strains to stress factors experienced by the bacteria. The high proportion of nsSNPs and deletions observed in specific genes may have contributed to phenotypic consequences including slow growth. Further functional biochemical studies addressing specific SNPs and gene deletions associated with lineage 7 strains are warranted to delineate the relative association to virulence and relation to clinical presentation.

Abbreviations

3R genes: DNA repair, recombination and replication genes; COG; clusters of orthologous groups; ML, maximum likelihood; MIRU-VNTR, mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit-variable-number tandem-repeat; MTBC, mycobacterium tuberculosis complex; nsSNPs, non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms; SIT, spoligo international type; WGS, whole genome sequencing.

References

Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (2015). Accessed 30 Sep 2015

Coscolla M, Gagneux S. Consequences of genomic diversity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Semin Immunol. 2014;26:431–44.

Galagan JE. Genomic insights into tuberculosis. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:307–20.

Hershberg R, Lipatov M, Small PM, Sheffer H, Niemann S, Homolka S, et al. High functional diversity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis driven by genetic drift and human demography. PLoS Biol. 2008; doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060311.

de Jong BC, Antonio M, Gagneux S. Mycobacterium africanum--review of an important cause of human tuberculosis in West Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e744.

Gehre F, Otu J, DeRiemer K, de Sessions PF, Hibberd ML, Mulders W, et al. Deciphering the growth behavior of Mycobacterium africanum. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;16, e2220.

Blouin Y, Hauck Y, Soler C, Fabre M, Vong R, Dehan C. Significance of the identification in the Horn of Africa of an exceptionally deep branching Mycobacterium tuberculosis clade. PLoS One. 2013; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.005284.

Firdessa R, Berg S, Hailu E, Schelling E, Gumi B, Erenso G, et al. Mycobacterial lineages causing pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis, Ethiopia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:460–3.

Yimer SA, Hailu E, Derese Y, Bjune GA, Holm-Hansen C. Spoligotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. APMIS. 2013;121:878–85.

Comas I, Hailu E, Kiros T, Bekele S, Mekonnen W, Gumi B, et al. Population Genomics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Ethiopia Contradicts the Virgin Soil Hypothesis for Human Tuberculosis in Sub-Saharan Africa. Curr Biol. 2015;25:3260–6.

Yimer SA, Norheim G, Namouchi A, Zegeye ED, Kinander W, Tønjum T, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis lineage 7 strains are associated with prolonged patient delay in seeking treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. J ClinMicrobiol. 2015;53:1301–9.

van Klingeren B, Dessens-Kroon M, van der Laan T, Kremer K, van Soolingen D. Drug susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by use of a high-throughput, reproducible, absolute concentration method. J ClinMicrobiol. 2007;45:2662–8.

Siddiqi SH, Rüsch-Gerdes S. MGIT procedure manual. Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics, Geneva, Switzerland: Global Laboratory Initiative; 2006.

van Helden PD, Victor TC, Warren RM, van Helden EG. Isolation of DNA from Mycobacterium tubercolosis. Methods Mol Med. 2001;54:19–30.

García-Alcalde F, Okonechnikov K, Carbonell J, Cruz LM, Götz S, Tarazona S, et al. Qualimap: evaluating next-generation sequencing alignment data. Bioinformatics. 2012;15:2678–9.

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SA Mtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;15:2078–9.

Fan X, Zhou W, Chong Z, Nakhleh L, Chen K. Towards accurate characterization of clonal heterogeneity based on structural variation. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;8:299.

Ye K, Schulz MH, Long Q, Apweiler R, Ning Z. Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2865–71.

Tatusov RL, Fedorova ND, Jackson JD, Jacobs AR, Kiryutin B, Koonin EV. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;11:41.

Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science. 1997;278:631–7.

Maddison, W. P. and D.R. Maddison. 2015. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 3.04 http://mesquiteproject.org.

Miltgen J, Morillon M, Koeck JL, Varnerot A, Briant JF, Nguyen G, et al. Two Cases of Pulmonary Tuberculosis Caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis subsp canetti. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:1350–2.

Dos Vultos T, Mestre O, Rauzier J, Golec M, Rastogi N, Rasolofo V. Evolution and diversity of clonal bacteria: the paradigm of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2008;3(2):e1538.

Albert TJ, Dailidiene D, Dailide G, Norton JE, Kalia A, Richmond TA. Mutation discovery in bacterial genomes: metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Nat Methods. 2005;2:951–3.

Jin DJ, Gross CA. Characterization of the pleiotropic phenotypes of rifampin-resistant rpoB mutants of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5229–31.

Saviola B. Mycobacterium tuberculosis adaptation to survival in a human host. In: Science, Technology and Medicine open access publisher. 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/54956. Mycobacterium tuberculosis adaptation to survival in a human host. Accessed 16 Jun 2015.

Smith NH, Kremer K, Inwald J, Dale J, Driscoll JR, Gordon SV, et al. Ecotypes of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J Theor Biol. 2006;239:220–5.

Kuroda A, Tanaka S, Ikeda T, Kato J, Takiguchi N, Ohtake H. Inorganic polyphosphate kinase is required to stimulate protein degradation and for adaptation to amino acid starvation in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14264–9.

Zhan W, Wang Y, Lee OO, Tian R, Cao H, Gao Z, et al. Adaptation of intertidal biofilm communities is driven by metal ion and oxidative stresses. Scientific Reports 3. 2013 doi:10.1038/srep03180.

Pepperell CS1, Casto AM, Kitchen A, Granka JM, Cornejo OE, Holmes EC, et al. The role of selection in shaping diversity of natural M. tuberculosis populations. PLoS Pathog. 2013; doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003543.

Zhang H, Zhang Z, Yang J, He ZG. Functional characterization of DnaB helicase and its modulation by single-stranded DNA binding protein in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEBS J. 2014;281:1256–66.

Sassetti CM, Boyd DH, Rubin EJ. Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:77–84.

Walker TM, Ip CLC, Harrell RH, Evans JT, Kapatai G, Dedicoat MJ, et al. Whole-genome sequencing to delineate Mycobacterium tuberculosis outbreaks: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:137–46.

Gehre F, Ejo M, Fissette K, de Rijk P, Uwizeye C, Nduwamahoro E, et al. Shifts in Mycobacterial Populations and Emerging Drug-Resistance in West and Central Africa. Caramelli D, ed. PLoS One. 2014; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110393.

Groenheit R, Ghebremichae S, Svensson J, Rabna P, Colombatti R, Riccardi F, et al. The Guinea-Bissau family of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex revisited. PLoS One. 2011; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018601.

Koro Koro F, Kamdem Simo Y, Piam FF, Noeske J, Gutierrez C, Kuaban C, et al. Population dynamics of tuberculous Bacilli in Cameroon as assessed by spoligotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:299–302.

Ouassa T, Borroni E, Loukou GY, Faye-Kette H, Kouakou J, Menan H, et al. High prevalence of shared international type 53 among Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains in retreated patients from Côte d'Ivoire. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45363.

Yeboah-Manu D, Asante-Poku A, Bodmer T, Stucki D, Koram K, Bonsu F, et al. Genotypic diversity and drug susceptibility patterns among M. tuberculosis complex isolates from South-Western Ghana. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21906.

Mathema B, Kurepina N, Yang G, Shashkina E, Manca C, Mehaffy C, et al. Epidemiologic consequences of microvariation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2012;15:964–74.

Valway SE, Sanchez MP, Shinnick TF, Orme I, Agerton T, Hoy D, et al. An outbreak involving extensive transmission of a virulent strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:633–9.

Getahun M, Ameni G, Kebede A, Yaregal Z, Hailu E, Medihn G, et al. Molecular typing and drug sensitivity testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated by a community-based survey in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:751.

Acknowledgments

We thank patients for consenting to participate in the study. We also thank study health facilities in Amhara Region, Ethiopia for facilitating the study. We are grateful to the Armauer Hansen Research Institute (AHRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health for facilitating the transfer of lineage 7 strains for WGS at Oslo University Hospital.

Funding

Funding was received from the Research Council of Norway (RCN) FRIMEDBIO project # 204747 and RCN GLOBVAC projects #234506 and 192468. The funders did not have any role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and material

Sequence data have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive with the study accession code PRJEB13960”.

Authors’ contributions

TT & SY conceived the study and study design. SY initially collected the isolates. SY and EDZ performed specimen handling and cultivation. EDZ performed DNA isolation. AN performed the bioinformatics and statistical analyses. SY, TT and AN evaluated and interpreted the data and drafted the paper. All authors edited and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics in Eastern Norway (REK Øst) and the Ethiopian Science and Technology Ministry in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Written informed consent was obtained from the study participants before the study was commenced.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Is a table listing databases used for comparative analysis of WGS. (XLSX 12 kb)

Additional file 2:

Shows time of the primary lineage 7 expansion. (PDF 8 kb)

Additional file 3:

Is a table listing the SNPs in genes. (XLSX 11 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yimer, S.A., Namouchi, A., Zegeye, E.D. et al. Deciphering the recent phylogenetic expansion of the originally deeply rooted Mycobacterium tuberculosis lineage 7. BMC Evol Biol 16, 146 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-016-0715-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-016-0715-z