Abstract

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) accumulate in the organisms due to their hydrophobicity and resistance to xenobiotic metabolism. 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) is one of most representative POPs. Its pathophysiological effects have been extensively studied on many types of tissues but not on muscles. In this study, female C57BL/6J mouse model was used to analyze the long-term effects of maternal exposure to TCDD during gestation and lactation on the skeletal muscles (soleus, plantaris, and gastrocnemius) of the progeny during adulthood. The effects of re-exposure to TCDD in mice exposed during their development were also characterized. Female C57BL/6J mice were maternally exposed to TCDD or its vehicle (n-nonane in corn oil) and then re-exposed to TCDD or its vehicle at 9 weeks of age. The metabolites in the skeletal muscles were analyzed by gas chromatography–quadrupole time of flight-mass spectrometry (GC–qTOF-MS). Univariate analysis showed significant effects in certain metabolites in the skeletal muscle. It also showed that TCDD exerts a more significant impact on exposure to TCDD at 9 weeks of age than during maternal exposure for the soleus. On the other hand, TCDD exerts a more significant impact on mice maternally exposed to TCDD than at 9 weeks of age for the gastrocnemius. Multivariate analysis showed clear discrimination between the TCDD-exposed mice and the control. This study demonstrates the effects of TCDD observed following maternal exposure; some of them can be reinforced or attenuated by a re-exposure at the adult age, suggesting that the POP which mainly acts through the activation of the AhR leads to metabolic adaptation in the skeletal muscles. The period of exposure was a key factor in our study with TCDD playing a crucial role during the maternal period, as compared to when they were exposed at 9 weeks of age. It was inferred that disruption in amino acid metabolism might lead to a loss in muscle mass which may result in muscular atrophy. Our results also show that the metabolite profiles after perinatal exposure are different in different types of muscles even though they are all classified as skeletal muscles. Therefore, TCDD may affect the organism (specifically different skeletal muscles) in a non-homogenous manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

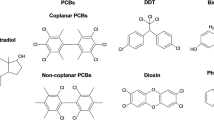

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are ‘forever’ compounds that tend to persist in the environment. They are of high concern since they are hydrophobic, resistant to chemical degradation, and thus tend to persist in ecosystems for a long period. Due to their lipophilic properties, POPs can bio-accumulate for long durations in fatty tissues (adipose tissue, liver, brain, etc.), in the bloodstream (perfluorinated compounds), and the dermal layer of many organisms (invertebrates, vertebrates); they can lead to various endocrine, immune and reproductive-related diseases such as obesity, diabetes and metabolic syndrome [20]. Some of these compounds include dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), organochlorine pesticides (OCs), as well as contaminants such as flame-retardants. TCDD (2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin), the Seveso dioxin, is an environmental contaminant with no distinguishable odor at room temperature that exists throughout the world. It is found mainly as a side-product in herbicides (e.g., chlorophenoxy herbicides and Agent Orange) or from the incomplete combustion of organic materials [30]. It is also one of the most toxic molecules [5]. Human exposure to TCDD results in diverse harmful effects like chloracne (an acne-like eruption) and has been associated with birth defects, cancers [6], and metabolic disruption [10].

In May 2001, the Stockholm Convention, conducted under the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) was implemented to protect human health and the environment from POPs including dioxins. In 2014, about 179 countries have adhered to this convention [1]. Despite the worldwide regulations to ban or reduce the levels of POPs for consumers, the impact of environmental exposure on consumers’ health is still of very high concern especially since the exposure is often chronic. The question of how POPs might affect human health remains poorly understood. One of the most intriguing aspects of POP toxicities is their impact on young individuals and the consequences of this perinatal exposure in adults or subsequent generations (transgenerational effects). Young individuals (including fetuses and embryos) are more vulnerable to exposure to pollutants because of their immature metabolic detoxicating systems [27]. Early exposure to POPs could lead to metabolic adaptations, allowing better protection of the organisms against potential re-exposures at later stages of development. Besides the metabolism of xenobiotics, the endogenous metabolisms (carbohydrates, lipids, amino acids, etc.) could also be impacted by such early exposure to pollutants.

Hence in this study, the effects of TCDD, a POP model known to activate the AhR signaling pathway which impacts general metabolism, were characterized in the skeletal muscles [19]. Indeed, the metabolic effects of TCDD have been extensively studied on the liver. Exposure of the host to TCDD results in disruption of several metabolic pathways including lipid metabolism and glycolysis [2, 17]. Subsequently, exposure to TCDD is also described as a cause of type 2 diabetes [13, 33]. However, few studies focused on the effects of TCDD in the skeletal muscles, which display adaptative and active metabolic functions [11, 12].

We used an original protocol of exposure to TCDD using a mouse model which allows the characterization of the metabolic consequences at the adulthood of low dose maternal exposure of TCDD, and to gain insight into the effects of perinatal exposure of TCDD on different skeletal muscles. As the mice exposed maternally are exposed again at adulthood, the protocol of exposure also allows the exploration of the mechanisms of adaptation to TCDD. GC–MS-qTOF coupled with univariate and multivariate statistical analyses was specifically used to study the metabolic disruptions in the skeletal muscles of mice exposed to TCDD. This study aims to shed new insights on the effects of TCDD on the skeletal muscles of mice during the perinatal period.

Material and methods

Chemicals and reagents

2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) (CAS# 1746-01-6) was purchased from LGC Standards; n-nonane (CAS# 111-84-2) and corn oil (CAS# 8001-30-7) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Analytical grade chemicals including methanol (CAS# 67-56-1), dichloromethane (CAS# 75-09-2), hexane (CAS# 110-54-3), chloroform (CAS# 67–66-3) and N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) (with 1% trimethylchlorosilane, TMCS) (CAS# 25561-30-2) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich.

Design of the study

The study conducted is the result of a larger study designed to investigate the transgenerational epigenetic effects of TCDD. To reduce the number of animals (3R) and to exploit the maximum number of biological samples, we chose to study the effect of perinatal exposure to TCDD on three types of skeletal muscles (soleus, plantaris, and gastrocnemius) focusing on metabolic regulations. As stated previously, few studies focused on the effects of TCDD in the skeletal muscles. The analysis of metabolites was performed on the soleus, plantaris, and gastrocnemius, collected from mice from the 4 groups of exposure (Nonane/Nonane, Nonane/TCDD, TCDD/Nonane, TCDD/TCDD) (Table 1). The tabulated results of the metabolomic raw data and multivariate analysis are given in Additional file 1: Material S1. The GC–MS-based metabolomic and correlation analysis are given in Additional file 2: Material S2.

Animals and treatment

C57BL/6J mice were provided by the CDTA (Center for Animal Distribution, Typing, and Archiving, CNRS, Orléans, France). Experiments on animals were performed in the animal facilities of CDTA (CNRS, Orléans, France) and subsequently at the animal facility of the BioMed Tech (Campus Saint Germain des Prés, INSERM US36, CNRS UMS2009, Université de Paris, Paris, France) according to previously reported procedures [15]. The European Communities Council directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of the animals were followed for the experiments using animals. Animals were treated humanely and with regard to the alleviation of suffering. All procedures were approved by the ethical committees for animal research of CNRS (Orléans) and Université de Paris (Paris) (n°CEEA34.XC.049.12).

Animals' maintenance and exposure to TCDD during the perinatal period and/or at 9 weeks of age

C57BL/6J mice were housed in a temperature-controlled room (22 ± 1 °C) with a relative humidity of 55 ± 5% and a 12 h light/dark cycle. Water and food (Safe® D30) were provided ad libitum.

Pregnant CD57Bl/6J mice were randomly administered either once-weekly oral dose of TCDD (1 ng TCDD/g body weight) or n-nonane/corn oil vehicle (1/24 v/v) on embryonic days E7.5, E14.5, and post-natal days P0.5, P7.5, P14.5, P21) in the CDTA animal facility by using a curved gavage probe fitted to the mouse mounted on a 1-mL syringe. The oral route of exposure was used to mimic the major route of exposure in humans. Each administration corresponded to 1 ng/g body weight of TCDD in n-nonane (corresponding to 0.2 µL/g body weight) or n-nonane alone (0.2 µL/g body weight) in the same total volume completed to 150 µL with corn oil. No statistically significant differences in mass were observed in the number of pups per litter among the different groups. The female pups were weaned at 3 weeks of age and allowed to acclimate to the BioMed Tech animal facility from 5 to 9 weeks of age.

The pups born in these two groups were re-exposed to either TCDD (1 ng/g body weight) or vehicle by a single oral dose, 24 h before tissue collection. Four exposure groups were thus designed: (i) maternal exposure to vehicle and re-exposure to vehicle at 9 weeks of age (Nonane/Nonane group or control); (ii) maternal exposure to vehicle and exposure to TCDD at 9 weeks of age (Nonane/TCDD group); (iii) maternal exposure to TCDD and exposure to vehicle at 9 weeks of age (TCDD/Nonane group); and (iv) maternal exposure to TCDD and re-exposure to TCDD at 9 weeks of age (TCDD/TCDD group) (Fig. 1).

Skeletal muscle tissue collection

Mice were fasted overnight before killing. Mice were weighed for body weight. Briefly, mice were anesthetized under isoflurane flow, the blood was then collected by the intracardiac route and, finally, mice were decapitated using a guillotine. Skeletal (soleus, plantaris, and gastrocnemius) muscles were rapidly dissected, weighed, and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Metabolite extraction and quantification by GC–qTOF-MS

Tissue metabolome extraction and derivatization

To each weighed and frozen skeletal muscle sample (average mass of soleus: 12 mg, plantaris: 25 mg, gastrocnemius: 190 mg), pre-cooled extraction solvents (1:1:1 v/v MeOH: CH2Cl2: Hexane; 15 µL/mg for muscles) were added. Each mixture was homogenized using a Bertin Minilys tissue homogenizer for 30–45 s with 30-45 s intervals. The homogenate was then vortexed for 20 s and then centrifuged at 12000g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was then dried under N2 and vacuum centrifugation. The dried extract was redissolved with CHCl3 and derivatized with 100 µL BSTFA + TCMS for at 60 °C for 30 min.

Metabolite separation and data acquisition

Gas chromatography–quadrupole time of flight-mass spectrometry (GC–qTOF-MS) (Agilent 7200, Santa Clara, CA) analysis was conducted. 1 µL of the sample extract was injected (split mode 20:1) with a PAL autosampler of the GC–qTOF-MS with helium as the carrier gas at a constant flow of 1.3 ml/min. The temperature program for the DB-5MS column began at 60 °C for 0.25 min and then ramped up at 12 °C/min to a final temperature of 280 °C. Mass scanning in EI (electron impact) mode was carried out for the range of 50-500 m/z at a scan time of 0.5 s. The detector voltage was set to 500 V and the setting of the electrospray ionization (EI) source was 70 eV. All data were collected consecutively in one analysis series to minimize chromatography difference and the injection sequence was randomized.

Statistical analysis and data processing

For qualitative analysis, Agilent Mass Hunter B.05.00 was used to deconvolute and evaluate the spectra. Metabolites were identified by matching their mass spectra to the NIST library. For quantitative analysis, the changes in metabolite concentrations were determined and normalized by calculating the percentages of the component peak areas in the total ion chromatograms. This is done by dividing each peak by the sum of all peaks, causing each peak value to become a fraction of the total. This is necessary for direct comparison of peak value between samples. This is because GC–MS data normalization usually works upon the principle that profiles contains relative information rather than absolute information. Hence, it should therefore be expressed in terms of ratios [26]. MetaboAnalyst 5.0 was used for correlation studies, univariate and multivariate analysis. Kruskal–Wallis test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test were the statistical methods chosen for statistical analysis. Statistical significance was determined based on p-value < 0.01, p-value < 0.05 and p-value < 0.1 to determine significantly altered metabolites. Pearson r correlation was performed for correlation studies. Diagrams were created with BioRender (available at Biorender.com).

Results

Univariate analysis

Three mice skeletal muscles representing the diversity of these tissues (i.e., soleus, plantaris, and gastrocnemius) were studied. As mentioned, the mice were maternally exposed to n-nonane/corn oil vehicle or TCDD and then exposed to n-nonane/corn oil vehicle or TCDD at 9 weeks of age (Table 1). This design allows the study of the consequences of perinatal exposure to TCDD (in terms of metabolic adaptations) and the subsequent consequences of a new exposure at the adult age. We identified several differentially expressed metabolites (DEM) in the 3 types of skeletal muscle samples, i.e., selected amino acids in soleus and plantaris and creatinine in gastrocnemius: the statistical data of significant compounds as the differentiating metabolites are summarized in Table 2 while the statistical data of the other metabolites for soleus, plantaris and gastrocnemius are summarized in Additional file 1: Tables S1–S5 in the Additional file 1: Material S1.

After tabulating the results in Table 2 and running statistical analysis, the Univariate Analysis was performed on the differential metabolites to compare the difference in metabolite changes in the skeletal muscles (Fig. 2).

Boxplot scoring (total area covered) of differential metabolites for the skeletal muscle (soleus, plantaris and gastrocnemius) of female mice maternally exposed to nonane or TCDD and then exposed to the nonane or TCDD at 9 weeks of age. Exposure to nonane at birth and at 9 weeks of age serves as the control. Plots were categorized as Nonane/Nonane, Nonane/TCDD, TCDD/Nonane and TCDD/TCDD. 25th, 50th (median labeled with a yellow dot) and 75th percentiles constitute the boxes. Whiskers extend to 1.5 interquartile range and outliers are displayed as black dots. The p-value of p < 0.1*, p < 0.05** and p < 0.01*** indicates that the result is significant

Based on the p-value obtained (Table 2), TCDD was found to exert a significant effect on the metabolites in the soleus of the female mice. Pairwise comparison was performed on the differential metabolites (Additional file 1: Table S5). For phosphate, with reference to the control group Nonane/Nonane, there is more significant effect on the Nonane/TCDD group (p-value = 0.02597) as compared to TCDD/No (p-value = 0.8357). For 2E-Butanedioc acid, TCDD has a more significant effect for Nonane/TCDD Group (p-value = 0.0001166) than TCDD/Nonane group (p-value of 0.04480). Similarly, for myo-inositol, with reference to the control group, there is more significant effect of Nonane/TCDD group (p-value = 0.004337) as compared to TCDD/No (p-value = 0.8398). Indeed, a double exposure (TCDD/TCDD group) leads to a significant effect on Phosphate (p-value = 0.0001166), L5-Oxoproline (p-value = 0.02215) and L-glutamic acid (p-value = 0.008159) with reference to the control group.

Based on the p-value obtained (Table 2), TCDD was found to exert a significant effect on the metabolites in the plantaris of the female mice. Pairwise comparison was performed on the differential metabolites (Additional file 1: Table S5). For L5-Oxoproline, with reference to the control group, there is a more significant effect on the TCDD/Nonane group (p-value = 0.007872) than on the Nonane/TCDD group (p-value = 0.6991). However, for pyrophosphate content, TCDD has a more significant impact on the Nonane/TCDD group (p-value = 0.01515) than TCDD/Nonane group (p-values = 0.07410). A double exposure (TCDD/TCDD group) leads to an even more significant effect on this metabolite (p-value = 0.01399).

Based on the p-value obtained (Table 2), TCDD was found to exert a significant effect on the metabolites in the gastrocnemius of the female mice. Pairwise comparison was performed on the differential metabolites (Additional file 1: Table S5). For Phosphate (p-value = 0.04113) and Arachidonic Acid (p-value = 0.001166), TCDD has a more significant effect on the Nonane/TCDD group than the TCDD/Nonane group. However, for Lactic Acid, with reference to the control, TCDD has a more significant effect on the TCDD/Nonane group (p-value = 0.01012) than the Nonane/TCDD group (p-value = 0.1320) Similarly for the TCDD/Nonane group of the metabolites Creatinine (p-value = 0.05128), L-Phenylalanine (p-value = 0.05128), Hypoxanthine (p-value = 0.0002861), L-Tyrosine (p-value = 0.09854) and Squalene (p-value = 0.0738). However, for Phosphate (p-value = 0.04113) and Arachidonic Acid (p-value = 0.001166), TCDD has a more significant effect on the TCDD/group than the TCDD/Nonane group. A double exposure (TCDD/TCDD group) leads to an even more significant effect for the metabolite Phosphate (p-value = 0.0004662).

Multivariate analysis

The same metabolites found in the soleus, plantaris, and gastrocnemius were also pooled together for multivariate analysis (Fig. 3). Principal component analysis with component 1 accounting for 28.5% of the variation and component 2 accounting for 15.9% of the variation showed that the 3 types of skeletal muscles are well discriminated. This shows that the metabolite profile is different in each muscle even though they are classified as skeletal muscles. Therefore, TCDD seems to affect the organism (specifically different skeletal muscles) in a non-homogenous manner.

The pooled comparison of all the 4 conditions in the soleus was considered. Principal component analysis with component 1 accounting for 30.3% of the variation and component 2 accounting for 12.9% of the variation (Additional file 1: Fig. S1) showed that there is a significant difference in metabolites between the maternal exposed group TCDD/Nonane and TCDD/TCDD on the TCDD-exposed group from the control group. As PCA is an unsupervised method, partial least-squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), a supervised method is carried out to supply information about each sample group. PLS-DA with component 1 accounting for 14.7% of the variation and component 2 accounting for 22.8% of the variation helps further distinguished the sample groups. Pairwise comparison in the soleus was also carried out to compare 1 sample group with another sample group. The different combination of the groups was compared with each other (Additional file 1: Fig. S2) using ortho-partial least squares-discriminant analyses (o-PLSDA). Regardless of the combination, the plots show clear discrimination between the groups.

The pooled comparison of all the 4 conditions in the plantaris was considered. PCA with component 1 accounting for 20.9% of the variation and component 2 accounting for 15.5% of the variation showed some difference between the groups (Additional file 1: Fig. S3). PLS-DA with component 1 accounting for 9.0% of the variation and component 2 accounting for 12.9% of the variation helps further distinguished the sample groups. There is an overlap of the TCDD/TCDD group with both Nonane/TCDD and TCDD/Nonane groups. However, they are distinguished from the control group. For pairwise comparison, the different combination of the groups was compared with each other (Additional file 1: Fig. S4). When Nonane/Nonane-treated mice were compared with TCDD/TCDD-treated mice and when Nonane/TCDD-treated mice are compared to TCDD/TCDD-treated mice, there was slight overlap due to 1 data point serving as an outlier. Nonetheless, there is still clear discrimination between the 2 groups. As for the other combinations, the plots show clear discrimination.

The pooled comparison of all the 4 conditions in the gastrocnemius was considered. PCA with component 1 accounting for 28.3% of the variation and component 2 accounting for 15.1% of the variation (Additional file 1: Fig. S5), showed some difference between groups TCDD/Nonane and other groups. From PCA, the data points of the other group seem to overlaps with the one from the control group (Nonane/Nonane). As PCA is an unsupervised method, PLS-DA with component 1 accounting for 21.1% of the variation and component 2 accounting for 15.0% of the variation helps further distinguished the sample groups (Additional file 1: Fig. S5). From PLS-DA, the other groups are well distinguished from the control group. This might be an indication that in the gastrocnemius, TCDD has a higher metabolic impact when the mice were maternally exposed than at 9 weeks of age. However, such a result is not conclusive. Hence, pairwise analysis was performed. For pairwise comparison in the gastrocnemius (Additional file 1: Fig. S6), regardless of the combination, the plots show clear discrimination between groups.

Correlation studies

Correlation studies of the similar metabolites found in the skeletal muscles: soleus, plantaris, and gastrocnemius were conducted. Such associations between metabolite levels can provide a promising additional source of information about the overall metabolic state in the skeletal muscles. The metabolites detected in each type of skeletal muscle were pooled together and subjected to Pearson r correlation (Fig. 4). The values of each metabolite are listed in Additional file 2: Material S2.

The differential metabolites common to all 3 types of skeletal muscle were considered. Lactic Acid has a relatively strong negative correlation with L-valine (− 0.4910). L5-oxoproline has a relatively strong negative correlation with 9-octadecanoic acid (− 0.4733), 9,12-octadecanoic acid (− 0.5048), L-proline (− 0.5745) and Pyrophosphate (− 0.4591). L-glutamic acid has a strong positive correlation with Aspartic Acid (0.538) and negative correlation with α-D-glucose (− 0.4513). Creatinine has a strong negative correlation with stearic acid (− 0.4836) and strong positive correlation with myo-inositol (0.4517) and α-D-glucose (0.4895) Myo-inositol has a strong positive correlation with α-D-glucose (0.6268) and β-D-glucose (0.5689). have a strong negative correlation with α-D-glucose has strong negative correlation with stearic acid (− 0.5059) and L-glutamic acid (− 0.4513) and strong positive correlation with pyrophosphate (0.5892), L-phenylalanine (0.4807), L-Tyrosine (0.5872), Creatinine (0.4895), Myo-inositol (0.6268) and β-D-glucose (0.7285).

Discussion

An overview of metabolism in skeletal muscles and its relationship with the intermediate metabolism of amino acids is shown (Fig. 5).

Amino acids that are naturally produced in the body are essential for muscle growth. Glutamine is one of the most important amino acids of the intermediate metabolism during the process, especially in muscle cells [31]. Other essential amino acids include L5-oxoproline, a precursor to glutamate [18], and glutamic acid, which exists as glutamate at physiological pH. As seen from the correlation studies, the metabolism of glutamine is linked with Fatty Acid metabolism whereby cells synthesized fatty acid via acetyl-CoA [32]. This is to ensure proper cell functioning. Other amino acids like proline and L5-oxoproline are produced through the catalytic activity of 5-oxoprolinase. This enzyme is ATP-dependent enzyme, thus reinforcing the correlation between L5-oxoproline and pyrophosphate. Other studies have also pointed out correlation between plasma L-phenylalanine and L-glutamine, in the occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma [21]. In our study, while we did not observe an alteration of glutamine levels, it is intriguing to quantify modifications in the content of amino acids which are metabolically linked to this important amino acid. It is possible to pinpoint various mechanisms that give rise to observed correlations between metabolite levels. From the univariate analysis, TCDD down-regulates the level of L-glutamic acid and L-phenylalanine in the soleus and L5-oxoproline in the plantaris. Hence, this observation (still, observed in different muscles) is coherent with the influence of TCDD on the occurrence of muscle wasting syndrome, characterized by loss of weight and muscular atrophy [23]. Moreover, L-glutamic acid is linked to aspartic acid which is then linked to metabolic pathways (e.g., conversion into oxaloacetate) involving carbohydrates [3, 29]. Thus, it is also coherent with L-glutamic acid linked to α-D-glucose.

Creatinine is a breakdown product of creatine phosphate from muscle and protein metabolism. It is released at a constant rate by the body (depending on muscle mass). Creatinine excretion is also influenced by muscle mass because creatinine formation occurs almost exclusively in the muscle [4]. From the results, it can be noted that TCDD exposure maternally results in a decrease in creatinine in the gastrocnemius part of the muscle, suggesting that in this part of the body, the catabolism of creatine phosphate is altered.

Dietary intakes of non-essential amino acids such as glutamate can have an impact on the growth of organisms [35]. Glutamate falls into this category; supplementation or a diet rich in this amino acid increases growth in vertebrates or protects against severe pathologies such as stroke in pigs and humans [24, 28] This effect of glutamate could be related to the stimulation of signaling pathways leading to the production of proteins like mTOR [34]. In rodents, TCDD administration is associated with cachexia, i.e., loss of muscle mass, and death [8]. The effect of TCDD is therefore consistent with the decrease in intramuscular glutamate concentrations (here in the soleus), but also with the decrease in creatinine observed in the gastrocnemius.

Several studies have reported an effect of TCDD in favor of a Warburg effect [25] leading to a favored glycolytic metabolism at the expense of mitochondrial metabolic processes. The reduction of the latter could lead to a depletion of the anaplerotic functions of the Krebs cycle, in particular for the use of alpha-ketoglutarate to maintain intracellular glutamate levels. This effect of TCDD (observed upon chronic and acute exposures) is to be compared with those of other toxins such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) which can also cause a decrease in protein synthesis and increase their degradation in muscle [14] and induce a loss of muscle protein or muscle atrophy. This decrease in glutamate concentrations could also impact glutathione levels [9]. Glutamate supplementation in pathophysiological situations may promote AKT/FOXO and mTOR signaling pathways and counteract this muscle loss [16]. However, this effect remains controversial but potentially related to compartmentalization effects of glutamate depending on the route of administration [7]. The effects of phenylalanine on muscle are less well known individually, but as an essential amino acid, a decrease in phenylalanine concentration may also affect muscle growth.

In fact, studies conducted in humans on the loss of muscle tissue are quite rare; one of the most frequently reported effects is the wasting syndrome associated with cachexia. For example, US veterans of the Vietnam War contaminated with Agent Orange, itself contaminated with TCDD, show cachexia for those with the higher levels of contamination; however, this is mainly related to a significant loss of fatty tissues [22]. The weight loss is classically described as being related to inflammatory processes. In animals, one of the consequences of TCDD exposure is also an inflammation [22].

Finally, it must be noticed that most effects of TCDD are observed following maternal exposure; some of them can be reinforced (e.g., L5-Oxoproline in the soleus) or attenuated (e.g., L-Glutamic Acid in the soleus) by a re-exposure at the adult age suggesting that the POP which mainly acts through the activation of the AhR leads to metabolic adaptation in the muscles. The metabolic, genomic and epigenomic consequences of TCDD exposures should be further explored in subsequent studies.

Conclusion and future work

TCDD disrupts various metabolites, particularly the levels of certain amino acids, carbohydrates, fatty acid and creatinine in the skeletal muscles. The period of exposure was a key factor in our study with TCDD playing a crucial role during the maternal period, as compared to when they were exposed at 9 weeks of age. It was inferred that disruption in amino acid metabolism might lead to a loss in muscle mass which may result in muscular atrophy. Our results also show that the metabolite profiles after perinatal exposure are different in different types of muscles even though they are all classified as skeletal muscles. Therefore, TCDD may affect the organism (specifically different skeletal muscles) in a non-homogenous manner.

As this is the first TCDD–muscle metabolic study, the future work may include the expansion of this model to study the effects of mixtures of POPs at different dosages on the skeletal muscles of mice and other organs like hearts, lungs, and kidneys to provide a more precise cartography of POPs distribution.

References

Alharbi OML, Basheer AA, Khattab RA, Ali I (2018) Health and environmental effects of persistent organic pollutants. J Mol Liq. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2018.05.029

Angrish MM, Dominici CY, Zacharewski TR (2013) TCDD-Elicited effects on liver, serum, and adipose lipid composition in C57BL/6 mice. Toxicol Sci 131(1):108–115. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfs277

Azevedo RA (2002) Analysis of the aspartic acid metabolic pathway using mutant genes. Amino Acids 22(3):217–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007260200010

Baxmann AC, Ahmed MS, Marques NC, Menon VB, Pereira AB, Kirsztajn GM, Heilberg IP (2008) Influence of muscle mass and physical activity on serum and urinary creatinine and serum cystatin C. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3(2):348–354. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.02870707

Bock KW, Köhle C (2006) Ah receptor: dioxin-mediated toxic responses as hints to deregulated physiologic functions. Biochem Pharmacol 72(4):393–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2006.01.017

Boffetta P, Mundt KA, Adami HO, Cole P, Mandel JS (2011) TCDD and cancer: a critical review of epidemiologic studies. Crit Rev Toxicol 41(7):622–636. https://doi.org/10.3109/10408444.2011.560141

Boutry C, Matsumoto H, Bos C, Moinard C, Cynober L, Yin Y, Tomé D, Blachier F (2012) Decreased glutamate, glutamine and citrulline concentrations in plasma and muscle in endotoxemia cannot be reversed by glutamate or glutamine supplementation: Aprimary intestinal defect? Amino Acids 43(4):1485–1498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-012-1221-2

Clark GC, Taylor MJ (1994) Tumor necrosis factor involvement in the toxicity of TCDD: The role of endotoxin in the response. Exp Clin Immunogenet 11(2–3):136–141. https://doi.org/10.1159/000424204

Engelen MPKJ, Schols AMWJ, Does JD, Deutz NEP, Wouters EFM (2000) Altered glutamate metabolism is associated with reduced muscle glutathione levels in patients with emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161(1):98–103. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.9901031

Fader KA, Nault R, Zhang C, Kumagai K, Harkema JR, Zacharewski TR (2017) 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD)-elicited effects on bile acid homeostasis: Alterations in biosynthesis, enterohepatic circulation, and microbial metabolism. Sci Rep 7(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05656-8

Guo J, Sartor M, Karyala S, Medvedovic M, Kann S, Puga A, Ryan P, Tomlinson CR (2004) Expression of genes in the TGF-β signaling pathway is significantly deregulated in smooth muscle cells from aorta of aryl hydrocarbon receptor knockout mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 194(1):79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2003.09.002

Hofsteen P, Plavicki J, Johnson SD, Peterson RE, Heideman W (2013) Sox9b is required for epicardium formation and plays a role in TCDD-induced heart malformation in zebrafish. Mol Pharmacol 84(3):353–360. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.113.086413

Hoyeck MP, Blair H, Ibrahim M, Solanki S, Elsawy M, Prakash A, Rick KRC, Matteo G, O’Dwyer S, Bruin JE (2020) Long-term metabolic consequences of acute dioxin exposure differ between male and female mice. Sci Rep 10(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-57973-0

Jepson MM, Pell JM, Bates PC, Millward DJ (1986) The effects of endotoxaemia on protein metabolism in skeletal muscle and liver of fed and fasted rats. Biochemical Journal 235(2):329–336. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj2350329

Joffin N, Noirez P, Antignac JP, Kim MJ, Marchand P, Falabregue M, Le Bizec B, Forest C, Emond C, Barouki R, Coumoul X (2018) Release and toxicity of adipose tissue-stored TCDD: direct evidence from a xenografted fat model. Environ Int 121(June):1113–1120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.10.027

Kang P, Wang X, Wu H, Zhu H, Hou Y, Wang L, Liu Y (2017) Glutamate alleviates muscle protein loss by modulating TLR4, NODs, Akt/FOXO and mTOR signaling pathways in LPS-challenged piglets. PLoS ONE 12(8):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182246

Kennedy LH, Sutter CH, Carrion SL, Tran QT, Bodreddigari S, Kensicki E, Mohney RP, Sutter TR (2013) 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-mediated production of reactive oxygen species is an essential step in the mechanism of action to accelerate human keratinocyte differentiation. Toxicol Sci 132(1):235–249. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfs325

Kumar A, Bachhawat AK (2012) Pyroglutamic acid: throwing light on a lightly studied metabolite. Curr Sci 102(2):288–297

Larigot L, Benoit L, Koual M, Tomkiewicz C, Barouki R, Coumoul X (2022) Aryl hydrocarbon receptor and its diverse ligands and functions: an exposome receptor. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 62(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-052220-115707

Lesage G (2015) Persistent organic pollutant. In: Giorno L, Drioli E (eds) Encyclopedia of membranes. Springer, Berlin, pp 1–2 (10.1007/978-3-642-40872-4)

Liang KH, Cheng ML, Lo CJ, Lin YH, Lai MW, Lin WR, Yeh CT (2020) Plasma phenylalanine and glutamine concentrations correlate with subsequent hepatocellular carcinoma occurrence in liver cirrhosis patients: an exploratory study. Sci Rep 10(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67971-x

Matsumura F (2003) On the significance of the role of cellular stress response reactions in the toxic actions of dioxin. Biochem Pharmacol 66:527–540

Max SR, Silbergeld EK (1987) Skeletal muscle glucocorticoid receptor and glutamine synthetase activity in the wasting syndrome in rats treated with 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 87:523–527

Nagata C, Wada K, Tamura T, Kawachi T, Konishi K, Tsuji M, Nakamura K (2015) Dietary intakes of glutamic acid and glycine are associated with stroke mortality in Japanese adults. J Nutr 145(4):720–728. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.114.201293

Nault R, Fader KA, Kirby MP, Ahmed S, Matthews J, Jones AD, Lunt SY, Zacharewski TR (2016) Pyruvate kinase isoform switching and hepatic metabolic reprogramming by the environmental contaminant 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Toxicol Sci 149(2):358–371. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfv245

Noonan MJ, Tinnesand HV, Buesching CD (2018) Normalizing gas-chromatography–mass spectrometry data: method choice can alter biological inference. BioEssays 40(6):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201700210

Olson KR, Morton LW (2019) Long-term fate of agent orange and dioxin TCDD contaminated soils and sediments in vietnam hotspots. Open J Soil Sci 09(01):1–34. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojss.2019.91001

Rezaei R, Knabe DA, Tekwe CD, Dahanayaka S, Ficken MD, Fielder SE, Eide SJ, Lovering SL, Wu G (2013) Dietary supplementation with monosodium glutamate is safe and improves growth performance in postweaning pigs. Amino Acids 44(3):911–923. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-012-1420-x

Rubi B, Del Arco A, Bartley C, Satrustegui J, Maechler P (2004) The malate-aspartate NADH shuttle member aralar1 determines glucose metabolic fate, mitochondrial activity, and insulin secretion in beta cells. J Biol Chem 279(53):55659–55666. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M409303200

Schecter A, Birnbaum L, Ryan JJ, Constable JD (2006) Dioxins: an overview. Environ Res 101(3):419–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2005.12.003

Tirapegui J, Cruzat VF (2015) Glutamine and skeletal muscle. Gln Clin Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-1932-1_38

Tumanov S, Bulusu V, Kamphorst JJ (2015) Analysis of fatty acid metabolism using stable isotope tracers and mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.mie.2015.05.017

White SS, Birnbaum LS (2009) An overview of the effects of dioxins and dioxin-like compounds on vertebrates, as documented in human and ecological epidemiology. J Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev 27(4):197–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/10590500903310047

Wu G (1998) Intestinal mucosal amino acid catabolism. J Nutr 128(8):1249. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/128.8.1249

Wu G, Wu Z, Dai Z, Yang Y, Wang W, Liu C, Wang B, Wang J, Yin Y (2013) Dietary requirements of “nutritionally non-essential amino acids” by animals and humans. Amino Acids 44(4):1107–1113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-012-1444-2

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Ministry of Education (R-143-000-B48-114), Université de Paris-National University of Singapore (NUS) Programme (R-143-000-B18-133), and Alexandre Diet from the CDTA (CNRS, Orléans, 3B rue de la Ferollerie, 45071 Orléans cedex 2).

Funding

Ministry of Education—Singapore, R-143-000-B48-114, Sam Li,USPC-NUS, Alexandre Diet from the CDTA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GL: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, data curation, writing—original draft. LJ: investigation, methodology. HD: investigation, methodology. AKCL: investigation, methodology. MH: investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing. EB: investigation, methodology writing—review and editing. CC: investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing. PN: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing. XC: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing. SFYL: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

The tabulated results of the Metabolomic Statistical data and Multivariate Analysis are given in Additional file 1: Material S1.

Additional file 2:

The tabulated results of the GC–MS-Raw Data and correlation analysis are given in Additional file 2: Material S2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lam, G., Juricek, L., Dayal, H. et al. Toxicological effects of 2,3,7,8 tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin on the skeletal muscle of mice during the perinatal period: a metabolomics study. Environ Sci Eur 34, 57 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-022-00633-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-022-00633-z