Abstract

Background

In past decades, laparoscopic surgery has been introduced for the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). Recently, additional studies comparing laparoscopic versus open surgery for gastric GISTs have been published, and an updated meta-analysis of this subject is necessary.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. Comparative studies of laparoscopic and open surgery for gastric GISTs published before June 2014 were identified from databases. The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale was used to perform quality assessment and original data were extracted. The statistical software STATA (version 12.0) was used for the meta-analysis.

Results

Finally, 22 studies, including a total of 1,166 cases, meet the inclusion criteria for meta-analysis. The operation time was similar between laparoscopic and open surgery. Compared to open surgery, laparoscopic resection was associated withless blood loss (WMD = -58.91 ml; 95% CI, -84.60 to -33.22 ml; P <0.01); earlier time to flatus (WMD = -1.31 d; 95% CI, -1.56 to -1.06, P <0.01) and oral diet (WMD = -1.75 d; 95% CI, -2.12 to -1.39; P <0.01); shorter hospital stay (WMD = -3.68 d; 95% CI, -4.47 to -2.88; P <0.01); and decreased overall complications (relative risk = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.37 to 0.89; P = 0.01). For long-term outcomes, there were no significant differences between two surgical procedures on recurrence.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic surgery for gastric GISTs is acceptable for selective patients with better short-term outcomes compared with open surgery. The long-term survival situation of patients mainly depends on the nature of tumor itself, and laparoscopic surgery was not associated with worse oncological outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumor in the gastrointestinal tract and are often characterized by cellular markers, such as CD117 (a c-kit gene proto-oncogene product) and CD34 (a human progenitor cell antigen) [1–3]. GISTs, which frequently occur in the stomach and small intestine [2], have malignant potential, and recurrence of GISTs often occurs at the peritoneal surface or liver [4]. Targeted therapies have been developed for GISTs, but surgical resection remains the optimal initial treatment approach for primary GISTs with no evidence of metastasis. The surgical principles of gastrointestinal stromal tumor comprise en bloc resection (R0 resection) with avoidance of rupture, which may result in peritoneal seeding. In addition, lymphadenectomy is not indicated in GISTs because of a very low propensity for lymph node metastases [5].

With the development of minimally invasive surgical approaches, laparoscopic surgery (LAP) for gastrointestinal stromal tumors has evolved rapidly over the past decades. Various types of laparoscopic approaches for GISTs have been performed in a few specialized centers, including wedge resection of the stomach, intragastric tumor resection, and combined endoscopic-laparoscopic resection [6–9]. Owing to the technique difficulty and relative rarity of GISTs, there is few study of large scale of patients reporting the short- and long-term results for LAP for GISTs compared with open surgery (OPEN). To address these issues, our team conducted the following meta-analysis to compare short-term and long-term results of patients undergoing LAP.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science to identify articles published up to June 2014. The search terms included ‘gastrointestinal stromal tumor’, ‘GIST’, ‘laparoscop*’, ‘gastrectomy’ and “gastric resection’. A personal search was also performed with reference lists of the retrieved relevant articles and reviews to identify additional trials and ensure that all the potential studies were included. The language of the articles was limited to English and Chinese according to the reviewers’ language competence.

Study selection

The inclusion criteria were as follows: comparative, peer-reviewed studies of LAP versus OPEN for GISTs for which the full text of the article was available. If two or more studies from the same institution, the most recent study or that including informative data was selected unless the reports were from different time periods. We excluded studies including: GISTs out of the stomach; complicated with mixed disease, such as gastric cancer; studies in which fewer than two relevant indexes were reported, or where it was difficult to calculate these from the results; and studies where the measured outcomes were not clearly presented in the literature.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two researchers independently extracted the data and disagreement was resolved through discussion. Extracted data included author, study period, geographical region, number of patients, operation time, blood loss, time to flatus, time to oral intake, length of hospital stay, morbidity, mortality, and long-term outcomes. The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) was used as an assessment tool. This scale varies from zero to nine stars: studies with a score equal to or higher than six were considered methodologically sound.

Outcome definition and Statistical analysis

Postoperative complications were classified as systematic complications (cardiovascular, respiratory or metabolic events; nonsurgical infections; deep venous thrombosis; and pulmonary embolism) or surgical complications (any anastomotic leakage or fistula, any complication that required reoperation, intra-abdominal collections, wound complications, bleeding events, pancreatitis, ileus, delayed gastric emptying, and anastomotic stricture). This classification system is based on the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center complication reporting system [10]. Continuous variables were assessed using weighted mean difference (WMD), and dichotomous variables were analyzed using the risk ratio (RR). If the study provided medians and ranges instead of means and standard deviations, we estimated the means and standard deviations as described by Hozo et al. [11]. Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated by the Higgins I2 statistic [12]. Based on method reported by DerSimonian and Laird [13], substantial significance was set when P < 0.10 and a random effect model was used. We hypothesized the outcomes of the comparison may be affected by the uneven distribution of the surgical types between the LAP and OPEN groups, especially by the relatively larger proportion of extended surgeries performed in the OPEN group. Thus, we performed a subgroup analysis of patients who underwent wedge resection in the two groups to eliminate the bias from the surgical type selection. We also conducted a subgroup analysis of studies that had comparable tumor size or risk index proposed by Fletcher et al. [3], which may have an impact on the operative outcomes. The potential publication bias based on the postoperative complications was assessed Begg’s test and funnel plots. Data analyses were performed using STATA (version 12.0). P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Studies selected

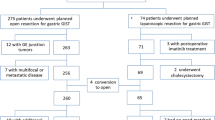

By the initial search, 768 potentially relevant articles were identified. After the titles and abstracts were reviewed, papers without comparison of LAP and OPEN were excluded, which left 28 comparative studies. An additional six [14–19] studies did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded. In total, 22 observational studies were obtained [20–41], all of which were accessible in full-text format. Twenty-one studies were published in English and one in Chinese. A flow chart of the search strategies, which contains reasons for exclusion, is presented in Figure 1.

Characteristics and quality of studies

A total of 1,166 patients were included in the analysis with 574 undergoing LAP (49.2%) and 592 undergoing OPEN (50.8%). They represented an international experience, with data included from 10 different countries or regions (six Japan, four United States, four China, two Korea, one United Kingdom, one Italy, one Belgium, one Austria, one Singapore and one Taiwan). According to the NOS, one out of the 22 observational studies got six stars, six articles got seven stars, eight articles got eight stars and the remaining seven got nine stars. Overall, all studies were evaluated as being moderate to high quality. The characteristics and methodological quality assessment scores of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Comparison of operative outcomes

The tumor size for LAP was significantly smaller than that for OPEN (WMD = -0.98 cm; 95% CI, -1.36 to -0.60; P <0.01; Figure 2). The present analysis showed no statistically significant difference in the operation time of the two groups (WMD = -11.22 min; 95% confidence interval (CI), -28.66 to 6.23; P = 0.21; Figure 3). Intraoperative blood loss was significantly lower in the LAP compared with the OPEN group (WMD = -58.91 ml; 95% CI, -84.60 to -33.22 ml; P <0.01; Figure 4).

Comparison of short-term postoperative outcomes

The outcomes also favored LAP in first flatus day (WMD = -1.31 d; 95% CI, -1.56 to -1.06; P <0.01; Figure 5) and first oral intake (WMD = -1.75 d; 95% CI, -2.12 to -1.39; P <0.01; Figure 6). Moreover, postoperative hospital day was 3.68 days shorter for LAP patients (WMD = -3.68 d; 95% CI, -4.47 to -2.88; P <0.01; Figure 7). With respect to the rate of overall postoperative complications, LAP is significantly superior to OPEN. The rate of overall postoperative complications was significantly lower for LAP (RR = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.37 to 0.89; P = 0.01; Figure 8). After further analysis, surgical complications were similar between the two groups (RR = 0.69; 95% CI, 0.37 to 1.29; P = 0.24). However, LAP was associated with a marginal reduction in systematic complications (RR = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.32 to 1.04; P = 0.07).

Comparison of oncological outcomes

15 studies reported tumor recurrence [21, 22, 24, 26–32, 34, 36, 39–41]. The recurrence risk in LAP was 3.6% (14 out of 388) and 9.7% (38 out of 393) in OPEN, and patients who underwent LAP were less likely than the OPEN group to have recurrence (RR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.28 to 0.93; P = 0.03; Figure 9). The available data about recurrence patterns and survival outcomes are summarized in Table 2.

Comparison of wedge resection

Comparison data of laparoscopic wedge resection and open wedge resection was available in eight studies[20, 22, 23, 26, 28, 30, 33, 34]. The overall effects such as operation time, blood loss, time to flatus or oral intake, hospital stay, and complications remained unchanged. However, in this subgroup analysis, the recurrence risk in LAP was 5.4% (7 out of 130) and 5.5% (9 out of 165) in OPEN, and the difference was not significant (RR = 1.01; 95% CI, 0.39 to 2.63; P = 0.99). The outcomes of subgroup analysis for studies of wedge resection are summarized in Table 3.

Subgroup analysis for studies with comparable tumor size or risk index

Thirteen studies qualified for a subgroup analysis for studies with comparable tumor size or risk index [20, 21, 23, 24, 26, 29, 30, 33, 34, 37–40]. Like the subgroup analysis for wedge resection, outcomes other than tumor recurrence remained unchanged. The recurrence risk was similar between LAP and OPEN (RR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.31 to 1.42; P = 0.29). The outcomes of subgroup analysis for studies with comparable tumor size or risk index are summarized in Table 4.

Publication bias

To test for publication bias, we used funnel plots and performed an Egger’s test based on the incidence of overall postoperative complications (Figure 10). The graphical funnel plot showed that none of the studies lay outside the 95% CI boundaries, and there was no evidence of publication bias.

Discussion

GISTs, although rare, are the most common mesenchymal tumors arising in the wall of the gastrointestinal tract. Surgery remains the mainstay of definitive therapy for non-metastatic GISTs. Recent evidence suggests that prognosis is mainly based on tumor size and histological features rather than wide resection margins [3, 42], which makes laparoscopic resection more popular for GIST treatment. Recently, some meta-analysises showed the superiority of LAP to OPEN [43, 44]. With the development of the laparoscopic technique, several additional articles that compare LAP with OPEN have been published since that analysis [36–41]. Therefore, we performed this updated meta-analysis to broaden the current knowledge on the clinical value of LAP.

We failed to include randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in this study. Although RCTs are first choice for a high-quality of meta-analysis, there are some hurdles to overcome such as learning curve effects, ethical issues, and the relatively low incidence of GISTs during the conduction of a high-quality RCT to evaluate this new surgical approach. Therefore, we made a number of efforts to ensure convincing results from non-RCTs, including the use of NOS to assess the quality of the studies and exclude low-quality studies; conducting subgroup analysis for studies of wedge resection, comparable tumor size or risk index to minimize the selection bias; and using funnel plots and Egger’s test to detect publication bias.

Our pooled analysis demonstrated faster gastrointestinal recovery in LAP. Reduced use of analgesic drugs, milder acute inflammatory response, and earlier postoperative activities are considered to be the main reasons for earlier gastrointestinal recovery in this type of surgery. The meta-analysis demonstrated a reduced number of complications in the LAP versus OPEN group, which may have resulted from a reduction in systematic complications. It is conceivable that surgical complications were similar between groups because LAP, though less invasive, results in the same resection extent as OPEN. Decreased pulmonary infection, which is the most common systemic complication, could explain the reduced systemic complications in LAP. Pain after surgery was less serious in LAP than in OPEN, reflected by a shorter duration or lower dosage of analgesics. The pain caused by the large incision as well as the use of tension sutures and abdominal bandages after laparotomy would deter patients’ attempts to cough, expectorate and perform breathing exercise effectively, resulting in complications such as pulmonary infection [45]. Our study demonstrated the postoperative hospital stay was 3.6 days shorter for LAP patients, which reasonably results from faster gastrointestinal recovery and a reduced number of complications in LAP.

The present analysis demonstrated that the operative time in the LAP group was similar to OPEN, which is in contrast to many other types of gastrointestinal surgery [46–49]. This result was mainly based on two factors. Lymphadenectomy, which is complicated and time-consuming under laparoscopy, is not generally required in LAP. Time spent on the establishment of pneumoperitoneum and the closure of the trocar incision and mini-laparotomy is likely to be shorter than the opening and closing of a laparotomy. Additionally, most studies involving less operative time in the LAP group had a relatively larger sample size or were recently published [29, 33–41], which might explain why the LAP appeared to be shorter than OPEN because of an accumulation of laparoscopic skills and the development of laparoscopic instruments.

Operative blood loss was shown in the pooled analysis to be lower in LAP. The reduced length of incision and the application of energy-dividing devices contribute to this reduction in blood loss. Moreover, the magnified view of laparoscopy allows for meticulous manipulation and reduction of injury. In our study, the asymmetric distribution of tumor size or extent of resection makes comparison of operative blood loss inherently flawed and at a high risk for confounding factors. So a subgroup analysis for studies with comparable tumor size or extent of resection was conducted, and less operative blood loss was still observed, which suggests that the technique of LAP itself might be the main reason for less operative blood loss.

Long-term survival remains critical for patients with GIST because of its malignant potential. Our study confirmed the safety of LAP for GISTs compared with OPEN. The postoperative recurrence in the LAP group was less than that of the OPEN group with statistical significance. However, the observed advantages of laparoscopy may be skewed by selection bias regarding tumor size. In several included studies, larger tumor size and higher risk classification were dominant in the OPEN group. According to the risk assessment classification [3], tumor size and mitotic index are two key factors on GISTs long-term outcomes. Thus, the studies with the same surgical approach (wedge resection) as well as those with comparable tumor size or risk classification were included in a subgroup analysis. The results of two subgroup analyses showed that the risk of postoperative recurrence in the LAP group was similar to the OPEN group. The increased experience of laparoscopic procedures, no touch of tumor and retrieving the tumor with an endobag [8, 36] may have contributed to this result. In addition, we also observed that the common sites of postoperative recurrence of GISTs included liver metastasis, peritoneal metastasis and local recurrence. Most cases of recurrence or metastasis had a trend toward higher-risk profiles and no port metastasis was identified, which suggests tumor recurrence is not clearly related to the surgical approach [21, 22, 24, 26, 27, 29, 31, 36, 39].

There are several limitations to our studies that must be taken into account when considering the results. First, all of the studies included in this meta-analysis are non-RCTs, which could lead to substantial selection and observation bias. Second, despite the majority of studies analyzed focusing only on GISTs, some included studies had several cases of other types of gastric submucosal tumors, such as neurilemmomas and leiomyomas. Because the sample size of remaining studies was still small for definitive conclusions on the safety and effectiveness of LAP, we did not exclude the study. Although such a low number does not imply a significant bias, it still can lead to clinical heterogeneity. Third, although the funnel plot showed that publication bias is unlikely, clinicians must be aware of possible publication bias when using evidence in clinical practice. Also, the follow-up duration of cases in the meta-analysis is too short for the low-risk GISTs to have developed tumor recurrence, which may have an influence on the tumor recurrence rate, and more long-term follow-up studies are awaited.

Conclusions

The current clinical evidence revealed that LAP is safe and feasible for the treatment of gastric GISTs in regards to short- and long-term outcomes. In selective patients, LAP is preferable compared with OPEN for its minimally invasive advantages. More well-designed RCTs or prospective cohort studies are awaited to adequately evaluate the status of laparoscopic resection for gastric GISTs.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- GISTs:

-

gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- LAP:

-

laparoscopic surgery

- NOS:

-

Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale

- OPEN:

-

open surgery

- RCTs:

-

randomized controlled trials

- RR:

-

relative risk

- WMD:

-

weighted mean difference.

References

Miettinen M, Majidi M, Lasota J: Pathology and diagnostic criteria of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): a review. Eur J Cancer. 2002, 38 (Suppl 5): S39-51.

Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Antonescu CR, DeMatteo RP, Ganjoo KN, Maki RG, Pisters PW, Raut CP, Riedel RF, Schuetze S, Sundar HM, Trent JC, Wayne J: NCCN Task Force report: update on the management of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010, 2: S1-41. quiz S42-44

Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, Miettinen M, O’Leary TJ, Remotti H, Rubin BP, Shmookler B, Sobin LH, Weiss SW: Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002, 33: 459-465.

DeMatteo RP, Lewis JJ, Leung D, Mudan SS, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF: Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recurrence patterns and prognostic factors for survival. Ann Surg. 2000, 231: 51-58.

Piso P, Schlitt HJ, Klempnauer J: Stromal sarcoma of the stomach: therapeutic considerations. Eur J Surg. 2000, 166: 954-958.

Xu X, Chen K, Zhou W, Zhang R, Wang J, Wu D, Mou Y: Laparoscopic transgastric resection of gastric submucosal tumors located near the esophagogastric junction. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013, 17: 1570-1575.

Kang WM, Yu JC, Ma ZQ, Zhao ZR, Meng QB, Ye X: Laparoscopic-endoscopic cooperative surgery for gastric submucosal tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2013, 19: 5720-5726.

Valle M, Federici O, Carboni F, Carpano S, Benedetti M, Garofalo A: Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: the role of laparoscopic resection. Single-centre experience of 38 cases. Surg Endosc. 2014, 28: 1040-1047.

Lee CH, Hyun MH, Kwon YJ, Cho SI, Park SS: Deciding laparoscopic approaches for wedge resection in gastric submucosal tumors: a suggestive flow chart using three major determinants. J Am Coll Surg. 2012, 215: 831-840.

Grobmyer SR, Pieracci FM, Allen PJ, Brennan MF, Jaques DP: Defining morbidity after pancreaticoduodenectomy: use of a prospective complication grading system. J Am Coll Surg. 2007, 204: 356-364.

Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I: Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005, 5: 13-

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG: Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003, 327: 557-560.

DerSimonian R, Laird N: Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986, 7: 117-188.

Basu S, Balaji S, Bennett DH, Davies N: Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) and laparoscopic resection. Surg Endosc. 2007, 21: 1685-1689.

Chen YH, Liu KH, Yeh CN, Hsu JT, Liu YY, Tsai CY, Chiu CT, Jan YY, Yeh TS: Laparoscopic resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: safe, efficient, and comparable oncologic outcomes. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012, 22: 7587-7563.

Fisher SB, Kim SC, Kooby DA, Cardona K, Russell MC, Delman KA, Staley CA, Maithel SK: Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a single institution experience of 176 surgical patients. Am Surg. 2013, 79: 657-665.

Otani Y, Furukawa T, Yoshida M, Saikawa Y, Wada N, Ueda M, Kubota T, Mukai M, Kameyama K, Sugino Y, Kumai K, Kitajima M: Operative indications for relatively small (2-5 cm) gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the stomach based on analysis of 60 operated cases. Surgery. 2006, 139: 484-492.

Wu JM, Yang CY, Wang MY, Wu MH, Lin MT: Gasless laparoscopy-assisted versus open resection for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the upper stomach: preliminary results. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010, 20: 725-729.

Bellorin O, Kundel A, Ni M, Litong D: Surgical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach. JSLS. 2014, 18: 46-49.

Shimizu S, Noshiro H, Nagai E, Uchiyama A, Mizumoto K, Tanaka M: Laparoscopic wedge resection of gastric submucosal tumors. Dig Surg. 2002, 19: 169-173.

Matthews BD, Walsh RM, Kercher KW, Sing RF, Pratt BL, Answini GA, Heniford BT: Laparoscopic vs open resection of gastric stromal tumors. Surg Endosc. 2002, 16: 803-807.

Ishikawa K, Inomata M, Etoh T, Shiromizu A, Shiraishi N, Arita T, Kitano S: Long-term outcome of laparoscopic wedge resection for gastric submucosal tumor compared with open wedge resection. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006, 16: 82-85.

Mochizuki Y, Kodera Y, Fujiwara M, Ito S, Yamamura Y, Sawaki A, Yamao K, Kato T: Laparoscopic wedge resection for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: initial experience. Surg Today. 2006, 36: 341-347.

Nishimura J, Nakajima K, Omori T, Takahashi T, Nishitani A, Ito T, Nishida T: Surgical strategy for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: laparoscopic vs. open resection. Surg Endosc. 2007, 21: 875-878.

Pitsinis V, Khan AZ: Cranshaw I. Allum WH: Single center experience of laparoscopic vs. open resection for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007, 54: 606-608.

Catena F, Di Battista M, Fusaroli P, Ansaloni L, Di Scioscio V, Santini D, Pantaleo M, Biasco G, Caletti G, Pinna A: Laparoscopic treatment of gastric GIST: report of 21 cases and literature’s review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008, 12: 561-568.

Silberhumer GR, Hufschmid M, Wrba F, Gyoeri G, Schoppmann S, Tribl B, Wenzl E, Prager G, Laengle F, Zacherl J: Surgery for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009, 13: 1213-1219.

Goh BK, Chow PK, Chok AY, Chan WH, Chung YF, Ong HS, Wong WK: Impact of the introduction of laparoscopic wedge resection as a surgical option for suspected small/medium-sized gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach on perioperative and oncologic outcomes. World J Surg. 2010, 34: 1847-1852.

Karakousis GC, Singer S, Zheng J, Gonen M, Coit D, DeMatteo RP, Strong VE: Laparoscopic versus open gastric resections for primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): a size-matched comparison. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011, 18: 1599-1605.

Dai QQ, Ye ZY, Zhang W, Lv ZY, Shao QS, Sun YS, Tao HQ: Laparoscopic versus open wedge resection for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinical controlled study. Chin J Gastrointest Surg. 2011, 14: 603-605.

De Vogelaere K, Hoorens A, Haentjens P, Delvaux G: Laparoscopic versus open resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach. Surg Endosc. 2013, 27: 1546-1554.

Melstrom LG, Phillips JD, Bentrem DJ, Wayne JD: Laparoscopic versus open resection of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012, 35: 451-454.

Lee HH, Hur H, Jung H, Park CH, Jeon HM, Song KY: Laparoscopic wedge resection for gastric submucosal tumors: a size-location matched case-control study. J Am Coll Surg. 2011, 212: 195-199.

Wan P, Yan C, Li C, Yan M, Zhu ZG: Choices of surgical approaches for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: laparoscopic versus open resection. Dig Surg. 2012, 29: 243-250.

Pucci MJ, Berger AC, Lim PW, Chojnacki KA, Rosato EL, Palazzo F: Laparoscopic approaches to gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an institutional review of 57 cases. Surg Endosc. 2012, 26: 3509-3514.

Kim KH, Kim MC, Jung GJ, Kim SJ, Jang JS, Kwon HC: Long term survival results for gastric GIST: is laparoscopic surgery for large gastric GIST feasible?. World J Surg Oncol. 2012, 10: 230-

Shu ZB, Sun LB, Li JP, Li YC, Ding DY: Laparoscopic versus open resection of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Chin J Cancer Res. 2013, 25: 175-182.

Lee PC, Lai PS, Yang CY, Chen CN, Lai IR, Lin MT: A gasless laparoscopic technique of wide excision for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor versus open method. World J Surg Oncol. 2013, 11: 44-

Kasetsermwiriya W, Nagai E, Nakata K, Nagayoshi Y, Shimizu S, Tanaka M: Laparoscopic surgery for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor is feasible irrespective of tumor size. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2014, 24: 123-129.

Lin J, Huang C, Zheng C, Li P, Xie J, Wang J, Lu J: Laparoscopic versus open gastric resection for larger than 5 cm primary gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): a size-matched comparison. Surg Endosc. 2014, [Epub ahead of print]

Takahashi T, Nakajima K, Miyazaki Y, Miyazaki Y, Kurokawa Y, Yamasaki M, Miyata H, Takiguchi S, Nishida T, Mori M, Doki Y: Surgical strategy for the gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) larger than 5 cm: laparoscopic surgery is feasible, safe, and oncologically acceptable. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014, [Epub ahead of print]

Miettinen M, El-Rifai WHL, Sobin L, Lasota J: Evaluation of malignancy and prognosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a review. Hum Pathol. 2002, 33: 478-483.

Koh YX, Chok AY, Zheng HL, Tan CS, Chow PK, Wong WK, Goh BK: A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing laparoscopic versus open gastric resections for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013, 20: 3549-3560.

Chen K, Zhou YC, Mou YP, Xu XW, Jin WW, Ajoodhea H: Systematic review and meta-analysis of safety and efficacy of laparoscopic resection for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach. Surg Endosc. 2014, [Epub ahead of print]

Ephgrave KS, Kleiman-Wexler R, Pfaller M, Booth B, Werkmeister L, Young S: Postoperative pneumonia: a prospective study of risk factors and morbidity. Surgery. 1993, 114: 815-819. discussion 819-821

Chen K, Xu XW, Zhang RC, Pan Y, Wu D, Mou YP: Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopy-assisted and open total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013, 19: 5365-5376.

Xie K, Zhu YP, Xu XW, Chen K, Yan JF, Mou YP: Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy is as safe and feasible as open procedure: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012, 18: 1959-1967.

Law WL, Lee YM, Choi HK, Seto CL, Ho JW: Impact of laparoscopic resection for colorectal cancer on operative outcomes and survival. Ann Surg. 2007, 245: 1-7.

Chen K, Mou YP, Xu XW, Cai JQ, Wu D, Pan Y, Zhang RC: Short-term surgical and long-term survival outcomes after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014, 14: 41-

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Department of Health of Zhejiang Province, China (grant number 2012ZDA024) and the Department of Education of Zhejiang Province, China (grant number Y201224313).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

QLC and YP wrote the manuscript; JQC, DW and KC performed the literature review and conducted the analysis of pooled data; YPM proofread and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Qi-Long Chen, Yu Pan contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, QL., Pan, Y., Cai, JQ. et al. Laparoscopic versus open resection for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Onc 12, 206 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-12-206

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-12-206