Abstract

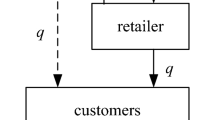

Product cannibalization can push some consumers to shift their purchasing preferences from new to used products. This is a costly issue for manufacturers, who have to adjust their pricing strategies accordingly to mitigate the negative effect of cannibalization. In this paper, we characterize an atypical channel to examine the effect of product cannibalization within the DellReconnect project. In particular, we investigate how the presence of a Goodwill agency in a second-hand market impacts the business of a manufacturer (e.g., Dell) in a new market through cannibalization, and how the manufacturer reacts to mitigate its effects. We show that even if the manufacturer adjusts its price to decrease the negative effects of cannibalization, this effect is so severe that it always loses some profits. Nevertheless, when the manufacturer provides some additional services to new consumers, the negative effects of cannibalization can be partially overcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Throughout the paper we will use the term manufacturer and Dell, and collector and Goodwill agency analogously.

Check the website www.dell.com for the complete list of services provided to new consumers by Dell.

In supply chain, the demand can be used as a proxy for social performance as it indicates the impact of firms’ strategies on the consumers’ willingness to (re)purchase and thus sales (De Giovanni et al, 2016).

While these simulations are less relevant for the purpose of the paper, we provide two Mathematica files which contains both the Mathematica code algorithm we have used to carry out the simulations that contains some dynamic objects. Interested readers can use the Mathematica file to comprehensively investigate all model parameters within some ranges.

The constant terms \(L_{k}\) are given as follows: \(L_{1}=2\beta _{C}^{2}+2\beta _{C}\gamma +\gamma ^{2},\ L_{2}=3\gamma ^{2}-4\beta _{C}\beta _{M},\,L_{3}=4\beta _{C}^{2}+6\beta _{C}\gamma +3\gamma ^{2},\,L_{4}=\alpha _{C}-(c_{p}-H+J)\beta _{C},\,L_{5}=\beta _{M}\gamma ^{2}+4\beta _{C}(\beta _{M}+\gamma )^{2}.\)

References

Amrouche N and Zaccour G (2007). Shelf-space allocation of national and private brands. European Journal of Operational Research 180(2):648–663.

Albuquerque P and Bronnenberg BJ (2009). Estimating demand heterogeneity using aggregated data: An application to the frozen pizza category. Marketing Science 28(2):356–372.

Atasu A, Guide DR and van Wassenhove LN (2010). So what if remanufacturing cannibalizes my new product sales? California Management Review 52(2):1–21.

Blattberg RC, Briesch R and Fox EJ (1995). How promotions work. Marketing Science 14(3):G122–G132.

Cachon GP (2003). Supply chain coordination with contracts. In Graves S and de Kok T (eds). Handbooks in Operations Research and Management Science: Supply Chain Management. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Cachon GP and Lariviere MA (2005). Supply chain coordination with revenue sharing contracts: Strength and limitations. Management Science 51(1):30–44.

Choi B and Ishii J (2010). Consumer Perception of Warranty as Signal of Quality: An Empirical Study of Power Train Warranties. Working paper. https://www3.amherst.edu/~jishii/files/WT_final_mar_2010.pdf. Accessed March 2010.

Corbett CJ and Savaskan RC (2003). Contracting and coordination in closed-loop supply chains. In Daniel V, Guide Jr R and Van Wassenhove LN (eds). Business Aspects of Closed-Loop Supply Chains: Exploring the Issues. Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Mellon University Press.

Dawes JD (2012). Brand-pack size cannibalization arising from temporary price promotions. Journal of Retailing 88(3):343–355.

De Giovanni P (2012). Do internal and external environmental management contribute to the triple bottom line? International Journal of Operations and Production Management 32(3):265–290.

De Giovanni P (2014). Environmental collaboration through a reverse revenue sharing contract. Annals of Operations Research 220(1):1–23.

De Giovanni P (2015). State- and control-dependent incentives in a closed-loop supply chain with dynamic returns. Dynamic Games and Applications 1(4):1–35.

De Giovanni P (2016). Coordination in a distribution channel with decisions on the nature of incentives and share-dependency on pricing. Journal of the Operational Research Society 67(8):1–16.

De Giovanni P and Zaccour G (2014). A two period game of closed-loop supply chain. European Journal of Operational Research 232(1):22–40.

De Giovanni P, Reddy PV and Zaccour G (2016). Incentive strategies for an optimal recovery program in a closed-loop supply chain. European Journal of Operational Research 249(2):605–617.

Debo LG, Tokay LB and Van Wassenhove LN (2006). Joint life-cycle dynamics of new and remanufactured products. Production and Operations Management 10(14):498–513.

Desai PS (2001). Quality segmentation in spatial markets: When does cannibalization affect product line design? Marketing Science 20(3):265–283.

Desai PS (2000). Multiple messages to retain retailers: Signaling new product demand. Marketing Science 19(4):381–389.

El Ouardighi F, Jørgensen S and Pasin F (2008). A dynamic game of operations and marketing management in a supply chain. International Journal of Game Theory Review 10(4):59–77.

Ferrer G and Ketzenberg ME (2004). Value of information in remanufacturing complex products. IIE Transactions 36(3):265–277.

Genc TS and De Giovanni P (2017). Trade-in and save: A two-period closed-loop supply chain game with price and technology dependent returns. International Journal of Production Economics 183(7):514–527.

Ghose A, Smith MD and Telang R (2006). Internet exchanges for used books: An empirical analysis of product cannibalization and welfare impact. Information Systems Research 17(1):3–19.

Green PE and Krieger AM (1992). An application of a product positioning model to pharmaceutical products. Marketing Science 11(2):117–132.

Guide VDR and Van Wassenhove LN (2009). The evolution of closed-loop supply chain research. Operations Research 57(1):10–18.

Guide VDR, Jayaraman V and Linton JD (2003). Building contingency planning for closed-loop supply chains with product recovery. Journal of Operations Management 21(3):259–279.

Guide VDR and Li J (2010). The potential for cannibalization of new products sales by remanufactured products. Decision Sciences 41(3):547–572.

Hattangadi V (2015). Is cannibalization good or bad? http://drvidyahattangadi.com/is-cannibalization-good-or-bad/. Accessed 12 January 2015.

Ingene C, Taboubi S and Zaccour G (2012). Game-theoretic coordination mechanisms in distribution channels: Integration and extensions for models without competition. Journal of Retailing 88(4):476–496.

Jayaraman V, Guide VDR and Srivastava R (1999). A closed-loop logistics model for remanufacturing. Journal of the Operational Research Society 50(5):497–508.

Jørgensen S, Taboubi S and Zaccour G (2001). Cooperative advertising in a marketing channel. Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications 110(1):145–158.

Karray S and Martin-Herran G (2009). A dynamic model for advertising and pricing competition between national and store brands. European Journal of Operational Research 193(2):451–467.

Karray S and Martin-Herran G (2008). Investigating the relationship between advertising and pricing in a channel with private label offering: A theoretic model. Review of Marketing Science 6(1):1–39.

Karray S and Zaccour G (2006). Could co-op advertising be a manufacturer’s counterstrategy to store brand? Journal of Business Research 59(9):1008–1015.

Mar-Ortiz J, Adenso-Diaz B and Gonzalez Velarde JL (2011). Design of recovery network for WEEE collection: The case of Galicia, Spain. Journal of the Operational Research Society 62(5):1471–1484.

Meredith L and Maki D (2001). Product cannibalization and the role of prices. Applied Economics 33(14):1785–1793.

Raju JS, Sethuraman R and Dhar SK (1995). The introduction and performance of store brands. Management Science 41(6):957–978.

Savaskan RC, Bhattacharya S and Van Wassenhove LN (2004). Closed loop supply chain models with product remanufacturing. Management Science 50(2):239–252.

Shubik M and Levitan R (1980). Market Structure and Behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Souza GC (2013). Closed-loop supply chains: A critical review, and future research. Decision Sciences 44(1):7–38.

Toktay B, Wein LM and Zenios SA (2000). Inventory management of remanufacturable products. Management Science 46(11):1412–1426.

van der Laan E and Teunter RH (2006). Simple heuristics for push and pull remanufacturing policies. European Journal of Operational Research 175(2):1084–1102.

van Heerde HJ, Srinivasan S and Dekimpe MG (2010) Estimating cannibalization rates for pioneering innovations. Marketing Science 29(6):1024–1039.

Vorasayan J and Ryan SM (2006). Optimal price and quantity of refurbished products. Production and Operations Management 15(3):369–383.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1: Analytical developments

Appendix 1: Analytical developments

Proof of Proposition 1

Since both players choose their strategies simultaneously, we will characterize the non-cooperative Nash equilibrium solution. Taking the derivatives of the profit functions in Eqs. (3) and (4) with respect to \(p_{M}\) and \(p_{C},\) respectively, and setting them equal to zero, we can derive the following reaction functions:

These reaction functions are upward sloping because \(\frac{\partial p_{M}}{\partial p_{C}}=\frac{\gamma }{2(\beta _{M}+\gamma )}>0\) and \(\frac{\partial p_{C}}{\partial p_{M}}=\frac{\gamma }{2(\beta _{C}+\gamma )}>0.\) Furthermore, the slope of the manufacturer’s reaction function is strictly greater than the slope of the collector’s reaction function. To see this, note that \(\frac{2(\beta _{M}+\gamma )}{\gamma }>\frac{\gamma }{2(\beta _{C}+\gamma )}\), implies that \(4(\beta _{M}+\gamma )(\beta _{C}+\gamma )-\gamma ^{2}>0\), which is always true in our model. This implies that the two reaction functions intersect only once and hence the optimal solution is unique.

Solving simultaneously the reaction functions yields the optimal prices; \( p_{M}^{\mathcal {B}}\) and \(p_{C}^{\mathcal {B}}\) are given in Eqs. (5) and (6) in Proposition 1. In addition, the Nash equilibrium prices of the manufacturer and the collector are stable, because if any of the players were to deviate from the optimal solution, based on the reaction functions, \( p_{M}(p_C)\) and \(p_C(p_M)\), the solution would converge back to \(p_{M}^{\mathcal {B}}\) and \(p_{C}^{\mathcal {B}}\).

The expressions for optimal profit of the manufacturer and the collector are

with \(\Omega _{1}={\rm DEN}\{ p_{M}^{\mathcal {B}}\}, \Omega _{2}={\rm NUM}\{ p_{C}^{\mathcal {B}}\} \) and \(\Omega _{3}={\rm NUM}\{ p_{M}^{\mathcal {B}}\} \square\).

Proof of Proposition 2

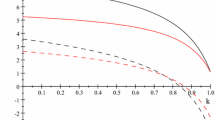

We compute the derivatives of firms’ prices with respect to the cannibalization effect, \(\gamma ,\) to show that:

-

\(\frac{\partial p_{M}^{\mathcal {B}}}{\partial \gamma }=-\frac{2(\alpha _{M}-H_{M}\beta _{M}) ( 4\beta _{C}^{2}+6\beta _{C}\gamma +3\gamma ^{2}) +( \alpha _{C}-H_{C}\beta _{C}) ( 3\gamma ^{2}-4\beta _{C}\beta _{M}) +2c_{p}\gamma ( \beta _{M}\gamma +\beta _{C}( 2\beta _{M}+\gamma ) ) }{[ 4(\beta _{M}+\gamma )(\beta _{C}+\gamma )-\gamma ^{2}] ^{2}}<0,\forall \gamma .\)

-

the sign of \(\frac{\partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {B}}}{\partial \gamma }= \frac{[ 2( \alpha _{C}-H_{C}\beta _{C}) +K_{1}] [ 4( \beta _{C}+\gamma ) ( \beta _{M}+\gamma ) -\gamma ^{2}] -2[ 2( \beta _{M}+\beta _{C}) +3\gamma ] [ 2( \alpha _{C}+H_{C}\beta _{C}) ( \beta _{M}+\gamma ) +\gamma K_{1}] }{[ 4(\beta _{M}+\gamma )(\beta _{C}+\gamma )-\gamma ^{2}] ^{2}}\) depends on \(\gamma ,\) where \( K_{1}=\alpha _{M}-H_{M}\beta _{M}+c_{p}( \beta _{M}+\gamma ) >0.\) Solving that derivative with respect to \(\gamma \) gives two roots, one positive and one negative; indeed, only one of those is feasible \(({\rm e.g.},\,\gamma \in (0,1)) \) and results in \(\gamma ^{ \mathcal {B}*}=\frac{2\beta _{M}K_{2}-\sqrt{( 2\beta _{M}K_{2}^{{}}) ^{2}+16\beta _{M}K_{3}[ \alpha _{M}\beta _{C}+\beta _{M}( ( 2H_{C}-H_{M}+c_{p}) \beta _{C}-2\alpha _{C}) ] }}{2K_{3}}\), where \(K_{2}=2[ 3( \alpha _{C}-H_{C}\beta _{C}) -2c_{p}\beta _{C}] >0\) and \(K_{3}=-( K_{2}+3( \alpha _{M}-H_{M}\beta _{M}) -c_{p}\beta _{M}) <0\). Consequently, \(\frac{\partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {B}}}{\partial \gamma } \ge 0,\forall \gamma \in (0,\gamma ^{\mathcal {B}*}]\) and \(\frac{ \partial p_{C}^{{\mathcal {B}}}}{\partial \gamma }<0\forall \gamma \in (\gamma ^{\mathcal {B}*},1].\) Intuitively, because \(p_{M}^{\mathcal {B} }>p_{C}^{\mathcal {B}}, \frac{\partial ( p_{M}^{\mathcal {B}}-p_{C}^{ \mathcal {B}}) }{\partial \gamma }<0,\forall \gamma .\) \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 3

\(\frac{{\rm d}\Pi _{M}^{\mathcal {B}}}{{\rm d}\gamma }= \frac{\partial \Pi _{M}^{\mathcal {B}}}{\partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {B}}}\frac{ \partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {B}}}{\partial p_{M}^{\mathcal {B}}}\frac{\partial p_{M}^{\mathcal {B}}}{\partial \gamma }-[p_{M}^{\mathcal {B}}-p_{C}^{\mathcal {B }}][p_{M}^{\mathcal {B}}-c_{P}]<0\) as \(\frac{\partial \Pi _{M}^{\mathcal {B}}}{ \partial p_{C}}>0, \frac{\partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {B}}}{\partial p_{M}^{ \mathcal {B}}}>0\), and \(\frac{\partial p_{M}^{\mathcal {B}}}{\partial \gamma } <0\) by Proposition 2. Similarly, \(\frac{{\rm d}\Pi _{C}^{\mathcal {B}}}{{\rm d}\gamma }= \frac{\partial \Pi _{C}^{\mathcal {B}}}{\partial p_{M}^{\mathcal {B}}}\frac{ \partial p_{M}^{\mathcal {B}}}{\partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {B}}}\frac{\partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {B}}}{\partial \gamma }+[p_{M}^{\mathcal {B}}-p_{C}^{\mathcal {B }}]p_{C}>0,\) as \(\frac{\partial \Pi _{C}^{\mathcal {B}}}{\partial p_{M}^{ \mathcal {B}}}>0, \frac{\partial p_{M}^{\mathcal {B}}}{\partial p_{C}^{ \mathcal {B}}}>0\), and \(\frac{\partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {B}}}{\partial \gamma } >0\) by Proposition 2. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 4

Since M and C choose their strategies simultaneously, we characterize first the non-cooperative Nash equilibrium solution. Using the given demand functions and the firms’ profit functions, we compute the derivatives of Eq. (3) with respect to \(p_{M}\) and A, and the derivative of Eq. (4) with respect to \(p_{C}\). Putting these derivatives equal to zero, the first-order necessary conditions lead to the following reaction functions:

From (12) and (13), we can see that the reaction curves for M and C are upward sloping because \(\frac{\partial p_{M}}{ \partial p_{C}}=\frac{\gamma }{2(\beta _{M}+\gamma )}>0,\frac{\partial p_{M} }{\partial A}=\frac{n}{2(\beta _{M}+\gamma )}>0,\frac{\partial p_{C}}{\partial p_{M}}=\frac{\gamma }{2(\beta _{C}+\gamma )}>0\), and \(\frac{ \partial A}{\partial p_{M}}=\frac{n}{l}>0\). Solving the reaction curves yields the optimal prices chosen by the firms, \(p_{M}^{\mathcal {A}}\) and \( p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}}\) as well as the optimal level of service efforts, A, as given in Proposition 4. The Nash equilibrium solution is unique and stable. To see this note that substituting \(A(p_{M})=\frac{ n(p_{M}-c_{p}+H_{M})}{l}\) into (12), we get \(\frac{\partial p_{M}(p_{C})}{\partial p_{C}}=\frac{\gamma l}{2(\beta _{M}+\gamma )l-n^{2}}\). Now, the reaction functions will intersect only once if \(\frac{2(\beta _{M}+\gamma )l-n^{2}}{\gamma l}>\frac{\gamma }{2(\beta _{C}+\gamma )}\), implying that \(4l(\beta _{M}+\gamma )(\beta _{C}+\gamma )-2n^{2}(\beta _{C}+\gamma )-l\gamma ^{2}>0\), which is always true in our model.

The expressions for optimal profits of the manufacturer and the collector are:

where \(\Psi _{1}={\rm DEN}\{ p_{M}^{\mathcal {A}}\},\; \Psi _{2}={\rm NUM}\{ p_{M}^{\mathcal {A}}\}, \Psi _{3}={\rm NUM}\{ p_{C}^{ \mathcal {A}}\} \) and \(\Psi _{4}={\rm NUM}\{ A\} \). \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 5

Consider the set of constant terms \( L_{k}>0,k=1,\ldots ,5\).Footnote 5 We compute the derivatives of the firms’ strategies with respect to \(\gamma \) to show that:

-

\(\frac{\partial p_{M}^{\mathcal {A}}}{\partial \gamma }=-\frac{ \begin{array}{c}l(2n^{2}((\alpha _{C}-(2H_{M}+H_{C})\beta _{C})\beta _{C}+(3H_{M}-cp)L_{1})+(\alpha _{C}-H_{C}\beta _{C})L_{2}\\ +2(H_{M}\beta _{M}-\alpha _{M})L_{3})-l(2c_{p}\gamma (\beta _{M}\gamma +\beta _{C}(2\beta _{M}+\gamma )))\end{array}}{( 2( \beta _{C}+\gamma ) ( 2l( \beta _{M}+\gamma ) -n^{2}) -l\gamma ^{2}) ^{2}}<0,\quad\forall \gamma \in [ 0,1] \),

-

\(\frac{\partial A}{\partial \gamma }=-\frac{\begin{array}{c}n(2n^{2}(\alpha _{C}\beta _{C}-H_{C}\beta _{C}^{2}+H_{M}L_{3}-cpL_{1})+l(( \alpha _{C}-H_{C}\beta _{C}) L_{2}-2c_{p}\gamma (\beta _{M}\gamma\\ +\beta _{C}(2\beta _{M}+\gamma ))+2(\alpha _{M}-H_{M}\beta _{M})L_{3}))\end{array}}{( 2( \beta _{C}+\gamma ) ( 2l( \beta _{M}+\gamma ) -n^{2}) -l\gamma ^{2}) ^{2}}<0,\quad \forall \gamma \in [ 0,1],\)

-

\(\frac{\partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}}}{\partial \gamma }=\frac{\left\{ \begin{array}{c} -2n^{4}L_{4}+ln^{2}\left[ 6L_{4}\beta _{M}+2(\alpha _{C}-H_{C}\beta _{C})(\beta _{M}+3\gamma )+(c_{p}-3H_{M})\gamma ^{2}+2\beta _{C}(2c_{p}\gamma +\alpha _{M})\right] \\ -l^{2}\left[ 2\left( \alpha _{M}-H_{M}\beta _{M}\right) L_{2}+2\left( \alpha _{C}-H_{C}\beta _{C}\right) L_{3}-c_{p}L_{5}\right] \end{array} \right\} }{( 2( \beta _{C}+\gamma ) ( 2l( \beta _{M}+\gamma ) -n^{2}) -l\gamma ^{2}) ^{2}}\) depends on the amplitude of \(\gamma .\) By solving \(\frac{\partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}}}{ \partial \gamma }\) with respect to \(\gamma \) we find two roots and only one of these is feasible \(({\rm e.g.},\,\gamma \in ( 0,1) ) \) and turns out to be: \(\gamma ^{\mathcal {A}*}=\frac{2ln^{2}((2c_{p}+3H_{C})\beta _{C}-3\alpha _{C})+\sqrt{\left\{ \begin{array}{c} 4l^{2}n^{4}((2c_{p}+3H_{C})\beta _{C}-3\alpha _{C})^{2}-4n^{2}l(c_{p}-3H_{M})[c_{p}l^{2}L_{5}-2L_{4}(n^{4}-3ln\beta _{M})\\ -l(l(2L_{3}(\alpha _{C}-H_{C}\beta _{C})+L_{2}(\alpha _{M}+H_{M}\beta _{M}))+2n^{2}(\alpha _{M}\beta _{C}-(\alpha _{C}-H_{C}\beta _{C})\beta _{M})] \end{array} \right\} }}{2ln^{2}(c_{p}-3H_{M})}.\) Thus \(\frac{\partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}} }{\partial \gamma }\ge 0\Rightarrow \forall \gamma \le \gamma ^{\mathcal {A} *}. \square \)

Proof of Proposition 5

\(\frac{{\rm d}\Pi _{M}(p_{M}^{\mathcal {A} },p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}},A)}{{\rm d}\gamma }=\frac{\partial \Pi _{M}^{\mathcal {A}}}{ \partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}}}\frac{\partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}}}{\partial p_{M}^{\mathcal {A}}}\frac{\partial p_{M}^{\mathcal {A}}}{\partial \gamma } -[p_{M}^{\mathcal {A}}-p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}}][p_{M}^{\mathcal {A}}-c_{p}^{ \mathcal {A}}]<0\) as \(\frac{\partial \Pi _{M}^{\mathcal {A}}}{\partial p_{C}^{ \mathcal {A}}}>0, \frac{\partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}}}{\partial p_{M}^{ \mathcal {A}}}>0\) (see Eq. 12), and \(\frac{\partial p_{M}^{\mathcal {A }}}{\partial \gamma }<0\) by Proposition 5. Similarly, \(\frac{{\rm d}\Pi _{C}^{ \mathcal {A}}(p_{M}^{\mathcal {A}},p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}},A)}{{\rm d}\gamma }=\frac{ \partial \Pi _{C}^{\mathcal {A}}}{\partial p_{M}^{\mathcal {A}}}\frac{\partial p_{M}^{\mathcal {A}}}{\partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}}}\frac{\partial p_{C}^{ \mathcal {A}}}{\partial \gamma ^{\mathcal {A}}}+p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}}[p_{M}^{ \mathcal {A}}-p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}}]>0, \frac{\partial \Pi _{M}^{\mathcal {A}} }{\partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}}}>0, \frac{\partial p_{M}^{\mathcal {A}}}{ \partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}}}>0\) (see Eq. 12), and \(\frac{\partial p_{C}^{\mathcal {A}}}{\partial \gamma }>0\) by Proposition 5. \(\square \)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De Giovanni, P., Ramani, V. Product cannibalization and the effect of a service strategy. J Oper Res Soc (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41274-017-0224-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41274-017-0224-5