Abstract

No studies to investigate the effect of a deprescribing intervention on the occurrence of potential prescribing omissions (PPOs) among elderly patients with polypharmacy have been conducted. Therefore, the effect of deprescribing on PPOs among elderly patients with polypharmacy was investigated. All 121 consecutive elderly patients who received in-hospital deprescribing interventions were evaluated. The primary outcome was any occurrence of PPOs based on the 2015 STOPP/START criteria. The proportion of patients who had any PPOs significantly increased after the deprescribing interventions (52.9% vs 77.7%, p < 0.001). In the multivariable analysis, older age was the only independent risk factor associated with an increased risk of any PPOs after the deprescribing interventions (OR 1.08, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.16). In-hospital deprescribing interventions for elderly patients with polypharmacy may increase the occurrence of PPOs. Further study is warranted to investigate the effects on clinical outcomes of the increased occurrence of PPOs due to the deprescribing intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polypharmacy refers to the use of multiple medications. In various studies, polypharmacy has been varyingly defined. Some investigators have defined it as the use of unnecessary medications1, while others have defined it as the use of two or more medications for the same conditions2. However, the most commonly used definition of polypharmacy is the numerical definition of polypharmacy of regular use of five or more medications regardless of whether they are necessary or unnecessary3, although there is no universal consensus for the optimal number of concomitant medications that would be defined as polypharmacy3,4.

Polypharmacy is common among elderly patients because they have multiple comorbidities that lead to the use of multiple medications5. Population-level data reports that 30 to 40% of noninstitutional people aged more or 65 years old take 5 or more medications6,7. The prevalence of polypharmacy roses to up to 60% in long-term care facilities8 and in-hospital settings9,10. Although prescribing medications is critical for elderly patient care, as the number of medications increases, the risk of adverse drug reactions increases11. In fact, polypharmacy for elderly patients is associated with an increased risk of adverse drug reactions12,13, fall injuries14, frailty15, and mortality16,17. Moreover, polypharmacy is also associated with nonadherence to medications18 and inappropriate prescription19,20. Therefore, some strategies to improve polypharmacy and inappropriate prescription among elderly patients are needed.

One strategy to resolve these problems is deprescribing, which is the systematic process of identifying and discontinuing medications for which the potential harms outweigh the potential benefits within the context of an individual patient’s care goals as supervised by healthcare professionals21. Deprescribing interventions can reduce inappropriate medications and medication-related problems22,23,24 and improve adherence to medications25. However, recent meta-analyses reported that deprescribing interventions cannot reduce the risk of hospital admission and death22,23,24. Thus, deprescribing interventions are still not proven to have a beneficial effect on clinically important outcomes except medication-related adverse events. It remains uncertain why deprescribing interventions cannot improve these outcomes.

Underprescribing is another important aspect of an inadequate prescription practice. The omission of drug therapy indicated for the prevention or treatment of specific diseases or conditions is associated with adverse outcomes26. Therefore, geriatric experts have recommended reducing potential prescribing omissions (PPOs) as much as possible among elderly patients27. However, the prevalence of PPOs is high in elderly patients20. Moreover, patients who take more medications have more PPOs28,29. Although the true reason for this remains unknown, it is thought that physicians may be reluctant to add new medications to polypharmacy29. In addition, the limited life expectancy and frailty of elderly patients may prevent physicians from prescribing preventive medications.

The relationship between deprescribing and underprescribing is complicated. For example, statins are beneficial for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD), even in elderly patients. Therefore, unless statins have been prescribed for elderly patients with CVD, this would be considered an inappropriate prescribing omission. However, statin use may be discouraged for the secondary prevention of CVD in patients with advanced illness or limited life expectancy30. In this case, deprescribing statins for these patients would be justified. However, given that estimation of the prognosis of elderly patients is difficult31, physicians’ underestimation of patients’ life expectancy may result in an unintentional increase in PPOs due to deprescribing. Moreover, an intervention to improve PPOs is not included in the deprescribing intervention. Therefore, a lack of efficacy of the deprescribing intervention on clinically important outcomes may be caused by the increase or lack of change of PPOs.

Nonetheless, no studies have been conducted to investigate the effect of the deprescribing intervention on the occurrence of PPOs among elderly patients with polypharmacy. Thus, our aim was to investigate the effect of the deprescribing intervention on the occurrence of PPOs among elderly patients with polypharmacy. The risk factors associated with the occurrence of PPOs after the in-hospital deprescribing interventions were also determined.

Results

A total of 121 elderly patients were included. The mean age of the patients was 80.5 (SD 7.4) years, 83 (68.6%) were women, and the mean Charlson Comorbidity Index score was 1.9 (SD 1.6) (Table 1 and Table S1). Twenty-four patients (19.8%) had dementia, 15 (12.4%) were nursing home residents, and 77 (63.6%) were able to walk independently. The most common admission ward was the orthopedic ward (n = 86, 85.2%), followed by the general surgery ward (n = 7, 5.8%). Only one patient (0.9%) died during the index hospitalization.

Although a mean of 0.8 medications were newly started during the index hospitalization, the mean number of total medications was significantly reduced after the deprescribing interventions (9.1 medications vs 4.7 medications, p < 0.001) (Table 2, Table S2, and Supplementary Data). The proportion of patients who took any PIMs was also significantly reduced after the deprescribing interventions (71.1% vs 43.0%, p < 0.001). However, the proportion of patients who had any PPOs significantly increased after the deprescribing interventions (52.9% vs 77.7%, p < 0.001). The most common type of PPO identified after the deprescribing interventions was musculoskeletal system drugs. More than half of all patients had at least one PPO for the musculoskeletal system. In the multivariable analysis, older age was the only independent risk factor associated with an increased risk of any PPOs after the deprescribing interventions (OR 1.08, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.16) (Table 3).

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the effect of a deprescribing intervention on the occurrence of PPOs among elderly patients with polypharmacy. Our study revealed that the in-hospital deprescribing intervention increased the occurrence of PPOs, although it significantly reduced the total number of medications and the use of any PIMs. Older age was the only independent predictive factor for any use of PPOs after the deprescribing intervention.

Several explanations for the increase in the use of PPOs after the in-hospital deprescribing intervention can be considered. First, some potentially necessary medications based on the 2015 START criteria might be judged to be unnecessary during the deprescribing intervention after sufficient assessment of these medications by the physicians who performed the deprescribing intervention. A previous study reported that one of the independent risk factors for not following the START criteria was patients’ inability to walk32. Moreover, given that older age was an independent predictive factor for the occurrence of PPOs after the deprescribing intervention, physicians might think that deprescribing potentially necessary medications based on the START criteria outweighs starting or continuing these medications from the viewpoint of the severe disability and limited life expectancy of the patients. If so, the occurrence of PPOs after the deprescribing intervention may be safe.

Second, the present study included only patients or their caregivers who chose to participate in the deprescribing intervention. Therefore, there might be some preferences on the part of the patients or their caregivers for the deprescribing intervention rather than starting new medications. Third, not starting or continuing potentially necessary medications may be caused by newly published evidence available after the release of the 2015 STOPP/START criteria32 and the limitations of past evidence. For example, a recent randomized controlled trial suggested that there was a lack of benefit of bisphosphonate with regard to preventing fractures in frail elderly women with osteoporosis33. Moreover, a past randomized controlled trial showing the efficacy of bisphosphonate excluded patients who could not walk independently before hip fracture34. This evidence may lead physicians not to start or continue potentially necessary medications among frail older patients.

Given that the effect of the deprescribing intervention on improving clinically important outcomes remains uncertain, further study is warranted to confirm our findings at other hospitals and investigate whether the increase in the occurrence of PPOs after the deprescribing intervention is safe or harmful for elderly patients with polypharmacy.

Several limitations need to be mentioned. First, this study had no control group that did not undergo the in-hospital deprescribing intervention. Therefore, the changes in PIMs and PPOs after the deprescribing interventions in this study did not necessarily derive from the effects of the intervention. However, given that the number of total medications and PIMs were unchanged or increased without the deprescribing intervention35,36, our results probably reflect the effect of the deprescribing intervention. Second, the information that was needed to evaluate PPOs was collected retrospectively. Therefore, the assessment of the occurrence of PPOs might be inaccurate37. Third, a single-center study design limits the generalization of our results. Fourth, only 121 elderly patients received the deprescribing intervention, although the interventions were performed over a 3-year period. Therefore, the low rate of recruitment among the patients who met the screening criteria for the deprescribing intervention also limits the generalizability of the present study. Fifth, geriatricians were not involved in the deprescribing intervention, although most past studies regarding deprescribing intervention also involved no geriatricians22,25. Sixth, our method of the deprescribing intervention may be implicit. Therefore, its external validity may be limited. However, we used a similar approach as the past study did38. Moreover, the method of deprescribing interventions used in some past studies is also implicit22. Finally, we did not collect information on medications after discharge. Given that discrepancies between medications at discharge and after discharge are common39, it is uncertain whether the effect of the deprescribing intervention continued after discharge.

Methods

Study setting and design

A retrospective single-center observational study was conducted by using medical electronic records to investigate the effect of deprescribing interventions on PPOs among hospitalized elderly patients with polypharmacy. Our hospital is a 350-bed acute care hospital, and it is one of the largest community hospitals in Utsunomiya, which has a population of approximately 0.5 million and is located in the central part of Japan. Geriatricians and geriatric care units are not available in our hospital. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the National Hospital Organization Tochigi Medical Center (No. 30-4). This study was conducted in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Research in Japan and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The need for individual informed consent was formally waived by the Medical Ethical Committee of the National Hospital Organization Tochigi Medical Center because deidentified data were collected without contacting the patients. However, as per Japanese Ethical Guidelines, we displayed an opt-out statement in the waiting room and webpage of the hospital to inform the study and provide the opportunity to refuse the use of data for the patients.

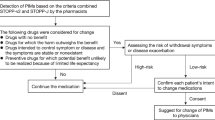

In-hospital deprescribing intervention

Our hospital started performing in-hospital deprescribing interventions for hospitalized elderly patients with polypharmacy in the orthopedic ward in January 201540. Other surgical wards, such as general surgery and urology, were added as target wards. The prevalence of polypharmacy is high among elderly patients hospitalized due to fractures41. Moreover, in our hospital, deprescribing intervention has been a routine care for elderly patients in the internal medicine ward since 201442. Therefore, we chose the orthopedic ward rather than the internal medicine ward. Patients aged 65 years old or older who were hospitalized in a target ward and took 5 or more regular medications were screened and contacted by pharmacists after admission. In addition, a list of medications that were judged to be potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) based on the 2015 screening tool of older persons’ prescriptions (STOPP) criteria27 were documented at medical records by the pharmacists. Then, patients consulted with internal medicine physicians who deprescribed inappropriate or unnecessary medications, if possible, during the index hospitalization. The internal medicine physicians evaluated the appropriateness of the polypharmacy and changed medications as needed. The appropriateness of medications was determined based on the STOPP criteria and the following38: (1) Does evidence exist supporting the use of the medication for the indication given for this patient? (2) Does an indication seem valid and relevant given this patient’s age and disability level? (3) Do the known possible adverse reactions of the medication outweigh the possible benefits for this patient? (4) Has any adverse event that may be related to the medication occurred? (5) Is there alternative medication or nonpharmacological treatment that may be safer and similarly effective compared with the current medication? The deprescribing intervention was performed until discharge. Four internal medicine physicians and three clinical pharmacists were mainly involved in this process. One of those physicians was trained in geriatrics, and all physicians received two lectures about polypharmacy and deprescribing annually since 2012. All three pharmacists, including MK and ST, were trained in geriatric pharmacy.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All consecutive elderly patients who received the in-hospital deprescribing intervention from internal medicine physicians from January 2015 to December 2017 were included. Patients aged less than 65 years old were excluded. The target patients were identified in the database of our hospital. During the study period, 123 patients received the in-hospital deprescribing intervention from internal medicine physicians. After excluding two patients aged less than 65 years old, a total of 121 patients were included in the final analysis.

Data collection and outcome measures

Pharmacists (MK, ST) reviewed the electronic medical records and retrieved information on patient age, sex, past medical history, medication use, Charlson Comorbidity Index score43, renal function, and prognosis. The Charlson Comorbidity Index score was determined via chart review. Information on medications at admission was based on a comprehensive list of current medications that was compiled by pharmacists after admission. Information on medications at discharge was based on the discharge prescriptions issued by physicians. For renal function, the best value during the index hospitalization was adopted.

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who had any PPOs. The secondary outcome was the proportion of patients who took any potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs). We defined PPOs and PIMs based on the 2015 screening tool of older persons’ prescriptions (STOPP) and the screening tool to alert to right treatment (START) criteria27. Section I of the START criteria (vaccine criteria) was excluded because information on vaccination was often not documented in the medical electronic records in our hospital. The total number of medications was also evaluated. Oral medications, inhalers, and injections were included. However, eye drops, intranasal infusers, topical medications, and over-the-counter drugs were excluded. As-needed medications were also excluded. Changes in the primary and secondary outcomes before and after the deprescribing intervention were investigated. The data collection and assessment of outcomes were performed from October 2019 to December 2019.

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics of patients are described with descriptive statistics. For the changes in the primary outcome, a comparison of the proportions of patients who had any PPOs at admission and at discharge was performed by using Fisher’s exact test. The same analysis was performed for the proportions of patients who took any PIMs. For the total number of medications, Student’s t-test was used to compare the totals at admission and at discharge. To determine the predictive factors associated with the occurrence of PPOs at discharge, a multivariable analysis using binary logistic regression was performed to examine the associations between PPOs at discharge and the following variables: age, sex, residence before admission, Charlson Comorbidity Index, ambulatory status, and number of medications at discharge. Stata V.15 (LightStone, Tokyo Japan) was used for these analyses. The level of statistical significance was set at 5%.

Conclusions

The in-hospital deprescribing intervention increased the occurrence of PPOs. Older age was the only independent predictive factor associated with the occurrence of PPOs after the deprescribing intervention. Further study is warranted to investigate the effect of the increased occurrence of PPOs due to the deprescribing intervention on clinical outcomes.

References

Colley, C. A. & Lucas, L. M. Polypharmacy: The cure becomes the disease. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 8(5), 278–283 (1993).

Brager, R. & Sloand, E. The spectrum of polypharmacy. Nurse Pract. 30(6), 44–50 (2005).

Masnoon, N., Shakib, S., Kalisch-Ellett, L. & Caughey, G. E. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 17, 230. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2 (2017).

Cadogan, C. A., Ryan, C. & Hughes, C. M. Appropriate polypharmacy and medicine safety: When many is not too many. Drug Saf. 39(2), 109–116 (2016).

Boyd, C. M. et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: Implications for pay for performance. JAMA 294, 716–724 (2005).

Nishtala, P. S. & Salahudeen, M. S. Temporal trends in polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy in older New Zealanders over a 9-year period: 2005–2013. Gerontology 61, 195–202 (2015).

Kantor, E. D., Rehm, C. D., Haas, J. S., Chan, A. T. & Giovannucci, E. L. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999–2012. JAMA 314(17), 1818–1831 (2015).

Jokanovic, N., Tan, E. C. K., Dooley, M. J., Kirkpatrick, C. M. & Bell, J. S. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. J. Am. Med. Dir Assoc. 16(6), 535.e1–12 (2015).

Nobili, A. et al. Polypharmacy, length of hospital stay, and in-hospital mortality among elderly patients in internal medicine wards. The REPOSI study. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 67, 507–519 (2011).

Gallagher, P. et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in an acutely ill population of older patients admitted to six European hospitals. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 67, 1175–1188 (2011).

Denham, M. J. Adverse drug reactions. Br. Med. Bull. 46(1), 53–62 (1990).

Alhawassi, T. M., Krass, I., Bajorek, B. V. & Pont, L. G. A systematic review of the prevalence and risk factors for adverse drug reactions in the elderly in the acute care setting. Clin. Interv. Aging 9, 2079–2086 (2014).

Oscanoa, T. J., Lizaraso, F. & Carvajal, A. Hospital admissions due to adverse drug reactions in the elderly. A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 73(6), 759–770 (2017).

Laflamme, L., Monárrez-Espino, J., Johnell, K., Elling, B. & Mӧller, J. Type, number or both? A population-based matched case-control study on the risk of fall injuries among older people and number of medications beyond fall-inducing drugs. PLoS ONE 10(3), e0123390 (2015).

Saum, K. U. et al. Is polypharmacy associated with frailty in older people? Results from the ESTHER cohort study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 65(2), e27–e32 (2017).

Leelakanok, N., Holcombe, A. L., Lund, B. C., Gu, X. & Schweizer, M. L. Association between polypharmacy and death: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 57(6), 729–738 (2017).

Chang, T. I. et al. Polypharmacy, hospitalization, and mortality risk: A nationwide cohort study. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 18964 (2020).

Stoehr, G. et al. Factors associated with adherence to medication regimens by older primary care patients: The Steel Valley Seniors Survey. Am. J. Geriatr. Pharmacother. 6(5), 255–263 (2008).

Cahir, C. et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and cost outcomes for older people: A national population study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 69(5), 543–552 (2010).

Tommelein, E. et al. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 71, 1415–1427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-015-1954-4 (2015).

Scott, I. A. et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: The process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern. Med. 175(5), 827–834. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0324 (2015).

Thillainadesan, J., Gnjidic, D., Green, S. & Hilmer, S. N. Impact of deprescribing interventions in older hospitalized patients on prescribing and clinical outcomes: A systematic review of randomised trials. Drugs Aging 35, 303–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-018-0536-4 (2018).

Page, A. T., Clifford, R. M., Potter, K., Schwartz, D. & Etherton-Beer, C. D. The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 82, 583–623. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12975 (2016).

Pruskowski, J. P., Springer, S., Thorpe, C. T., Klein-Fedyshin, M. & Handler, S. M. Does deprescribing improve quality of life? A systematic review of the literature. Drugs Aging 36(12), 1097–1110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00717-1 (2019).

Ulley, J., Harrop, D., Ali, A., Alton, S. & Davis, S. F. Deprescribing interventions and their impact on medication adherence in community-dwelling older adults with polypharmacy: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 19(1), 15 (2019).

Counter, D., Millar, J. W. T. & McLay, J. S. Hospital readmissions, mortality and potentially inappropriate prescribing: A retrospective study of older adults discharged from hospital. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 84(8), 1757–1763. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.13607 (2018).

O’Mahony, D. et al. TOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: Version 2. Age Ageing 44, 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/aful45 (2015).

Galvin, R. et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing and prescribing omissions in older Irish adults: Findings from The Irish LongituDinal Study on Ageing study (TILDA). Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 70, 599–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-014-1651-8 (2014).

Blanco-Reina, E., Ariza-Zafra, G., Ocaña-Riola, R., León-Ortíz, M. & Bellido-Estévez, I. Optimizing elderly pharmacotherapy: Polypharmacy vs. undertreatment. Are these two concepts related?. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 71(2), 199–207 (2015).

Kutner, J. S. et al. Safety and benefit of discontinuing statin therapy in the setting advanced, life-limiting illness. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 175(5), 691–700 (2015).

Gill, T. M., Gahbauer, E. A., Han, L. & Allore, H. G. Trajectories of disability in the last year of life. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 1173–1180 (2010).

Lozano-Montoya, I., Vélez-Diaz-Pallaréz, M., Delgado-Silveira, M.-E. & Jentoft, A. J. C. Potentially inappropriate prescribing detected by STOPP-START criteria: are they really inappropriate?. Age Ageing 44, 861–866. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv079 (2015).

Greenspan, S. L., Perera, S., Ferchak, M. A., Nace, D. A. & Resnick, N. M. Efficacy and safety of single-dose zolendronic acid for osteoporosis in frail elderly women: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 175(6), 913–921. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0747 (2015).

Lyles, K. W. et al. Zolendronic acid and clinical fractures and mortality after hip fracture. N. Engl. J. Med. 357(18), 1799–1809. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa074941 (2007).

Pérez, T. et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people in primary care and its association with hospital admission: Longitudinal study. BMJ 363, k4524. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k4524 (2018).

Juliano, A. C. D. S. R. S. et al. Inappropriate prescribing in older hospitalized adults: A comparison of medical specialists. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 66(2), 383–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15138 (2018).

Lönnbro, J. & Wallerstedt, S. M. Clinical relevance of the STOPP/START criteria in hip fracture patients. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 73, 499–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-016-2188-9 (2017).

Garfinkel, D. & Mangin, D. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults: Addressing polypharmacy. Arch. Intern. Med. 170(18), 1648–1654 (2010).

Coleman, E. A., Smith, J. D., Raha, D. & Min, S. J. Posthospital medication discrepancies: Prevalence and contributing factors. Arch. Intern. Med. 165(16), 1842–1847. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.16.1842 (2005).

Komagamine, J., Sugawara, K. & Hagane, K. Characteristics of elderly patients with polypharmacy who refuse to participate in an in-hospital deprescribing intervention: A retrospective cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 18, 96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0788-1 (2018).

Kragh, A., Elmståhl, S. & Atroshi, I. Older adults’ medication use 6 months before and after hip fracture: A population-based cohort study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 59, 863–868 (2011).

Komagamine, J. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications at admission and discharge among hospitalised elderly patients with acute medical illness at a single centre in Japan: a retrospective cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 8, e021152 (2018).

Charlson, M. E., Pompei, P., Ales, K. L. & MacKenzie, C. R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J. Chron. Dis. 40(5), 373–383 (1987).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K. conceived this study. J.K. and M.K. designed and wrote the protocol of this study. M.K. and S.T. collected data. J.K. analysed and guaranteed the data. J.K. and M.K. wrote the draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaminaga, M., Komagamine, J. & Tatsumi, S. The effects of in-hospital deprescribing on potential prescribing omission in hospitalized elderly patients with polypharmacy. Sci Rep 11, 8898 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88362-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88362-w

- Springer Nature Limited