Abstract

Background

Polypharmacy, and the associated adverse drug events such as non-adherence to prescriptions, is a common problem for elderly people living with multiple comorbidities. Deprescribing, i.e. the gradual withdrawal from medications with supervision by a healthcare professional, is regarded as a means of reducing adverse effects of multiple medications including non-adherence. This systematic review examines the evidence of deprescribing as an effective strategy for improving medication adherence amongst older, community dwelling adults.

Methods

A mixed methods review was undertaken. Eight bibliographic database and two clinical trials registers were searched between May and December 2017. Results were double screened in accordance with pre-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria related to polypharmacy, deprescribing and adherence in older, community dwelling populations. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used for quality appraisal and an a priori data collection instrument was used. For the quantitative studies, a narrative synthesis approach was taken. The qualitative data was analysed using framework analysis. Findings were integrated using a mixed methods technique. The review was performed in accordance with the PRISMA reporting statement.

Results

A total of 22 original studies were included, of which 12 were RCTs. Deprescribing with adherence as an outcome measure was identified in randomised controlled trials (RCTs), observational and cohort studies from 13 countries between 1996 and 2017. There were 17 pharmacy-led interventions; others were led by General Practitioners (GP) and nurses. Four studies demonstrated an overall reduction in medications of which all studies corresponded with improved adherence. A total of thirteen studies reported improved adherence of which 5 were RCTs. Adherence was reported as a secondary outcome in all but one study.

Conclusions

There is insufficient evidence to show that deprescribing improves medication adherence. Only 13 studies (of 22) reported adherence of which only 5 were randomised controlled trials. Older people are particularly susceptible to non-adherence due to multi-morbidity associated with polypharmacy. Bio-psycho-social factors including health literacy and multi-disciplinary team interventions influence adherence. The authors recommend further study into the efficacy and outcomes of medicines management interventions. A consensus on priority outcome measurements for prescribed medications is indicated.

Trial registration

PROSPERO number CRD42017075315.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The management of many chronic diseases depends chiefly on the assumption that the medications prescribed by the clinician are taken by the individual being treated. Medication adherence is defined as the extent to which prescribed medications are taken according to the dosage and frequency recommended by the provider [1]. It is estimated, however, that between 30 and 50% of people do not take their medications as prescribed [2]. Theories as to the causes of non-adherence generally recognise socio-economic, healthcare system, condition- and patient-related factors [3]. Methods to combat non-adherence are wide-ranging; from practical interventions, to behaviour change interventions targeting psychological barriers to medication use [4]. The resulting costs of non-adherence are both human, the individual not gaining the benefit of treatment, and economic [5,6,7], resulting in unused medication, for example. Older people are particularly susceptible to non-adherence due to multi-morbidity associated polypharmacy [8], and owing to particular constraints such as physical, cognitive or sensory impairments [9].

In this review polypharmacy is the taking of any medication that is potentially inappropriate, rather than exceeding a defined number of drugs [10] because adherence to an inappropriate medication can lead to harm. However, available evidence regarding polypharmacy and drug adherence in the older population living at home is scarce [11]. Most studies have focused on improving adherence to one drug group, and thus have limited applicability to the older population who commonly use multiple medications [12,13,14].

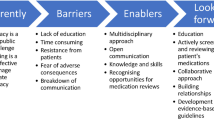

The term ‘deprescribing’ is the process of the gradual withdrawal and cessation of potentially inappropriate medications, supervised by a healthcare professional with the goal of reducing unnecessary medications and their related problems [15]. Deprescribing attempts to balance the potential for benefit and harm by systematically withdrawing inappropriate medications with the goal of managing polypharmacy and improving outcomes [16]. Guidelines that have been developed to facilitate this process advocate involving the individual themselves in decisions relating to their prescription [17,18,19,20]. In spite of their potential to improve safety, significant barriers to these interventions exist [21,22,23].

Previous studies have examined the impact of deprescribing processes in residential care settings [24]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there has been no investigation as to the potential of deprescribing as an effective strategy for improving medication adherence in community-dwelling older adults. This is a population who are largely independent and live in their own home, but for whom the number, dosage and complexity of medications demands considerable health literacy [25, 26].

The aim of the review was to explore the impact of deprescribing interventions on adherence measures in this unique population.

Methods

A mixed methods systematic review of the literature was undertaken on deprescribing interventions and medication adherence in community-dwelling older adults with polypharmacy. Registered as PROSPERO CRD42017075315, this systematic review used qualitative and quantitative data to explore a range of factors associated with the effectiveness of deprescribing interventions in tackling medication non-adherence, and in doing so, offers a more complete picture of the area of investigation [27]. The search, screening, quality appraisal and data extraction processes were led by an Information Scientist (DH) and the lead for the review team (JU). This systematic review is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement.

Eligibility criteria

Papers were selected using the criteria as follows. Study type: primary qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods studies were sought. Protocols, conference abstracts, academic thesis, editorials, commentaries and opinion articles were excluded. Review papers were excluded, but were used to cross-check for relevant primary papers. Population: papers must have reported data on community dwelling older people (aged ≥65 years) experiencing polypharmacy. In this review, polypharmacy is the taking of any medication that is potentially inappropriate, rather than exceeding a defined number of drugs [10]. Intervention: a paper must have explored the effect of a deprescribing intervention which included any medication review that was in line with the definition agreed by the Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe 2013. [28]. Comparator: a study must have included a control to have been eligible for inclusion. Outcomes: a paper must have reported data on adherence, measured by any means; i.e., pill count, self-reported, questionnaire, ‘drug or prescription or medications’ ‘renewal or refill’, blood level analysis. Adherence could have been reported as a primary or a secondary outcome. Any study that did not report adherence was excluded.

Search strategy

An information scientist (DH) undertook a comprehensive search of eight bibliographic databases between May and August 2017: ASSIA (ProQuest), CENTRAL (Wiley), CINAHL (EBSCO), MEDLINE (EBSCO), PsycINFO (ProQuest), Scopus (Elsevier), Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), Web of Science (Thomson Reuters). Two clinical trials registers were searched in December 2017: UK Clinical Trials Gateway (NHS, National Institute for Health Research), International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (World Health Organization).

The search strategy comprised four facets: (i) older people, and (ii) polypharmacy, deprescribing or medications reviews, and (iii) adherence or instruments/measurements relating to adherence, and (iv) the community setting, such as independent living, or the community based professional delivering the intervention. All terms were searched for in the title and abstract fields and controlled vocabulary terms were included where available. The Boolean operators AND and OR were used, alongside truncation, phrase searching and proximity operators. Only papers published in the English language were sought, no date limits were applied. The search syntax was adapted for use on each information source. The full search strategy, written up for MEDLINE (EBSCO) is provided in Additional file 1: Appendix 1.

Data management

The bibliographic software, RefWorks (ProQuest) was used to store and organise all results from the bibliographic databases, and Excel was used for results from the clinical trials registers. Microsoft Excel 2015 was used to support the selection of papers and data extraction process, and Microsoft Word 2015, the quality appraisal process.

Study selection

All papers retrieved from the literature searches were assessed against the inclusion criteria. The study selection process was piloted by all members of the review team using a sample of 100 papers. All results were independently screened by two members of the review team. In the first instance the title and abstract of all papers were screened to determine their relevancy, followed by a full text screening of all remaining papers. Any disagreement in screening outcome between reviewers was resolved through discussion or the use of a third reviewer. Reviewers were not blinded to a paper’s author/s.

Data extraction

An a priori data collection instrument was created and piloted by the review team. Data extraction was undertaken by one reviewer and double checked for accuracy by a second. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and further scrutiny of the included paper. Extracted data were as follows: information on the author/s, year of publication, name of paper, title of journal; the study setting, duration and geographic location; the study type, design, aim, objectives, context, and data collection and analysis techniques; the number of participants, participant demographics, e.g. age, gender, baseline cognitive function, number of medications taken, health conditions experienced; the aim and description of the intervention, the intervention instrument, baseline adherence, how the intervention was delivered; time from the intervention to the follow-up; theoretical framework underpinning an intervention; author stated strengths/weaknesses and conclusions; reviewers comments. Outcomes of adherence included: (i) the adherence measure reported, (ii) the number of drugs prescribed and their appropriateness, (iii) and whether the adherence measure improved with intervention or not. Secondary measures of interest included: self-reported quality of life, primary care visits, hospital visits and mortality; indicators of acceptability to users, and evidence of shared decision making.

Risk of bias in individual studies

The Mixed Methods Quality Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [29] was used to explore the risk of bias at study level. An overall quality score was attributed to each study. An incremental score of 25% is given for each of the four criteria met for quantitative and qualitative studies and each of the three criteria for mixed methods studies.

Data synthesis

Qualitative and quantitative data were analysed separately. If a paper reported mixed methods data, a decision was taken as to what the majority of the data comprised. The quantitative data was not homogenous; there was variability in data collection, data source, and statistical analysis across most studies. Therefore for the quantitative studies, a narrative synthesis approach was taken. The qualitative data was analysed using Framework Analysis [30]. Findings were integrated using the ‘Following a Thread’ technique described by O’Cathain et al., [31]. Using this approach all data sets were scanned for key themes and questions in need of further exploration.

Results

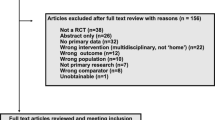

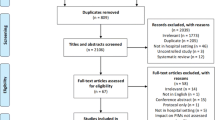

A total of 1980 unique papers were yielded from the database searches, and an additional 140 papers from the clinical trials registers searches. Screening title and abstracts resulted in 119 papers being retained from the database searches and 21 papers from the clinical trials registries. After full-text reading, author citation and reference list evaluation a total of 22 met the eligibility criteria and underwent quality appraisal and data extraction processes. Nine additional trials were found, but no data was found due to either non-publication or ongoing research. The literature review screening process is summarised in Fig. 1.

Outcomes from the MMAT exercise for the 22 papers from the database searches showed that ten studies scored 100%, six scored 75% and six scored 50% or less. Non-RCT data exhibited somewhat greater risk of bias (see MMAT summary Table 1). Quantitative and qualitative findings were collated but the framework analysis was limited by the very small amount of qualitative data about adherence, medicines’ management methods and patient outcomes. A summary of study characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Studies and participants

Twenty-two studies in 13 different countries were included (10 in Europe, 5 in North America, 7 elsewhere (Australia, New Zealand, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Jordan), with publication dates between 1996 and 2017, involving 5118 participants. Thirteen studies were controlled clinical trials (1 non-randomised), and nine were cross-sectional studies. The age range of the participants was 46 and 97 years. Three studies included patients < 65 years, 13 studies age range 65–85, 6 studies included patients >86y. Eight study interventions were based in primary care or GP practices, seven in community pharmacies, three in an outpatient clinic, two as home visits, one as remote prescribing and one from a community centre for older people. The follow-up period for the interventions ranged between four weeks and 41 months, with a mean of eight months.

Types of interventions

The healthcare professional leading the intervention varied significantly. Most commonly, a pharmacist led (in 18 studies [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48], while a GP and pharmacist co-led in 1 study [49], a GP alone in another study [50], a community nurse led in another study [51] and the participants themselves led in another [52]. While all interventions included a process of deprescribing, study interventions used ‘deprescribing’ specifically in nine studies [32, 35, 40, 42, 47, 48, 52, 53], while in 12 studies the description was ‘medication use review’ [33, 34, 36,37,38, 41, 43,44,45,46, 49,50,51].

Where specific deprescribing tools were used they included the GP-GP (good palliative-geriatric practice) [32], STOPP/START, 2 [32, 39], Beers, 1 [52], e-medicines information, one [35], IMAP (individualised medication assessment and planning program), 1 [42]. In four studies no particular deprescribing tool was mentioned [40, 47, 48, 52]. Only four of the 22 studies yielded significant reductions in tablet burden [32, 46, 47, 50]. Regime complexity, i.e. the frequency and dosing, was not recorded in any of the studies. Of those studies with no decrease in overall medications; seven demonstrated a comparable number pre- and post-intervention [33, 36, 42, 43, 45, 48, 52]; 1 study reported an overall increase [44], and nine did not record the numbers (either pre or post) [34, 35, 37,38,39,40,41, 49, 51, 53].

Medication adherence

Thirteen studies reported improved adherence following study interventions [32, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41, 43, 46, 47, 50] of which 5 studies were RCTs. Of the four studies that report a reduction in medication burden, all reported improved adherence [32, 46, 47, 50]. Exclusion of studies at moderate to high risk of bias (MMAT score 50% or less) did not alter the overall findings. The adherence tool varied between studies, but not to the same extent as the intervention tool. The Morisky-Green scale or a derivative was used in 10 studies [32,33,34,35, 38,39,40, 42, 46, 49, 52]; Medication possession ratio/pill count in five studies [36, 37, 43, 45, 49, 52]; self-report only in three studies [48, 50, 51] and self-report and pill count in three studies [44, 47, 50]. An unspecified adherence scale was used in one study [41]. All studies reported adherence as a secondary outcome, except Twigg [39] and Messerli [53]. The proposed mechanisms of success for those that reported improved adherence were: reduced number of medications, 1 [32]; good relationship between clinical professionals/ collaborative working, 3 [34, 43, 50]; practical aspect only, 1 [45]; educational or motivational impact, 5 [36, 38,39,40,41], both practical and behavioural impact, 3 [35, 37, 47].

In terms of the secondary measures of interest, self-reported quality of life was reported in five of the 22 studies [32, 34, 39, 44, 48], of which one study [39] reported an improvement. The other four studies had no statistical impact. Primary care visits were reported in four studies [32, 39, 40, 44] of which one study reported a change in number of visits [39] (an increase from a mean of 1.65 to 2.04 visits per patient in a 6 month period). Unplanned or emergency care visits were reported in 6 studies [32, 33, 39, 40, 42, 44]. Two studies suggested that interventions resulted in reductions to unplanned care but this was not statistically significant; four studies demonstrated no impact on unplanned or emergency care. Mortality was reported in four studies [32, 33, 44, 45]; none of these reported any impact.

Discussion

The issue of adherence is manifestly complicated. A broad range of studies was deliberately included to enhance understanding of the potential mechanisms of any intervention effect but qualitative data were limited. It is clear that no routine or consistent method of deprescribing is implemented, and no consistent outcome from the practice, such as a reduction in the number of prescriptions, is reported. Therefore it was impossible to demonstrate that an improved adherence was a consequence of a reduced medication burden.

Adherence is regarded as an important indicator of the quality of the doctor–patient relationship [54] and by extension that offered by other multidisciplinary team members. It is important to note that there are different understandings of adherence according to clinical and research priorities. This study identified that improved adherence depended on the measurement tool and the method of statistical analysis. For example, a self-report scale questionnaire would differ in analysis to the proportion of days covered. One study incorporated the understanding of the individual as to the purpose of each of their medications [41], where others merely counted the number of pills left at the end of a month [36, 37, 43, 47].

There is an extremely mixed body of literature reporting strategies to improve medication adherence [55]. Adherence was measured as a secondary outcome in all but two studies which meant that more subtle reasons for non-adherence could not be established from this review. Follow-up periods were generally short, making it difficult to draw any conclusions as to the lasting impact of the interventions themselves.

The range of professional practitioners engaged in deprescribing implies that international models of practice are continuing to adopt an interdisciplinary team approach. Of the three studies that did not involve pharmacists, none showed a difference in adherence measures. Of the 18 remaining studies, the majority (13 studies) demonstrated improved outcomes. From this review it would seem that pharmacist-led deprescribing interventions are effective.

Independent prescribing status in the UK has been awarded by the General Pharmaceutical Council since 2006 and nurses, podiatrists, physiotherapists and therapeutic radiographers may complete additional post-registration training to become independent prescribers [56]. One study commented that the success of the intervention depended, in large part, on the physician’s acceptance of the recommended changes in a person’s medications [34]. Collaborative working between professionals to achieve deprescribing or increased adherence may be key to the success of these interventions.

A systematic method of enhancing the quality of research into medication use is now being proposed, particularly focusing on seven factors that are consistent with the findings of this study; vulnerable patient populations; polypharmacy and multi-morbidity; person-centered practice and research; deprescribing or medicines use review; methodological development; variability in medication use; and national and international comparative research [56].

From this review there is little data suggesting that deprescribing interventions improve outcomes such as quality of life, primary or secondary care visits or affect mortality [57]. On the other hand, neither is there much evidence that these interventions lead to a negative impact on these measures; something that has already been suggested elsewhere [58]. Large RCTs evaluating multidisciplinary interventions and clinical outcomes of deprescribing are lacking [59,60,61], but there are examples of individual studies suggesting that deprescribing can improve outcomes such as falls, hospital admissions and mortality [62].

There was a surprisingly low level of reporting of socio-economic components. In a sub group analysis of four studies that reported both deprescribing with reduction in medication and an improvement in adherence the intervention cohort (N = 847) were 44% men and 56% women. The studies reported inconsistently, on marital status educational level and household income. Further consideration of these socio-economic components is indicated to deliver a patient-centred deprescribing process [63, 64].

The strengths of this review include careful attention to screening and data extraction of the adherence outcome and the focus on the outcome of the complex medicines management intervention. ‘Deprescribing’ was carefully defined to include all forms of medication review interventions where the intention was to reduce treatment burden.

The evidence found was from different study designs: RCTs, prospective/ retrospective cohort, prospective cross-sectional, cohort and prospective uncontrolled and is a limitation of the literature. Meta-analyses of data were not possible, and this is a limitation, owing to the diversity of measures used in calculating adherence. A number of potentially interesting sub-group analyses (e.g. ethnicity, degree of frailty, economic impact of intervention) could not be completed due to varied and incomplete reporting of populations studied, interventions delivered, and outcome measurements. Qualitative data analysis revealed a number of factors associated with non-adherence but limited narrative explanation was possible within the data.

Conclusion

This systematic review found that deprescribing as an intervention did not routinely improve medication adherence in this patient population. The theory that a reduced medication burden would improve adherence could not be substantiated in the literature. This is because the interventions described in the studies did not convincingly reduce medication burden. There is a range of bio-psycho-social factors reported that associate with improved adherence, but medicines review processes vary and rarely report the population demographic. Adherence is mostly reported as a secondary outcome and there is no standard report of successful adherence to medication. The authors recommend further study into the efficacy and outcomes of medicines management interventions. A consensus on priority outcome measurements for prescribed medications is indicated.

Abbreviations

- ASSIA:

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and abstracts

- CENTRAL:

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trails

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- MEDLINE:

-

Medical Literature

- MMAT:

-

Mixed Methods Quality Appraisal Tool

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis

- PROSPERO:

-

Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- PsycINFO:

-

Psychology Informatics

- RCT:

-

Randomised Controlled Trial

- USA:

-

United States of America

References

Cramer J, Roy A, Burrell A, Fairchild C, Fuldeore M, Ollendorf D, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11(1):44–7.

World Health Organization. Adherence to Long Term Therapies. Geneva: Evidence for Action; World Health Organization; 2003. http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_report/en.

Kardas P, Lewekm P, Matyjaszczyk M. Determinants of patient adherence: a review of systematic reviews. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:91.

Patton DE, Hughes CC, Ryan M. Theory-based interventions to improve medication adherence in older adults prescribed polypharmacy: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2017;34(2):97–113.

Laufs U, Rettig-Ewen V, Böhm M. Strategies to improve drug adherence. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(3):264–8.

Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–97.

Mickelson RS, Holden RJ. Medication adherence: staying within the boundaries of safety. Ergonomics. 2018;61(1):82–103.

Pérez-Jover V, Mira JJ, Carratala-Munuera C, Gil-Guillen VF, Basora J, López-Pineda A, et al. Inappropriate use of medication by elderly, polymedicated, or multipathological patients with chronic diseases. Int J Enviro Res Public Health. 2018;15(2):310.

Vlasnik JJ, Aliotta SL, DeLor B. Medication adherence: factors influencing compliance with prescribed medication plans. Case Manager. 2005;16(2):47–51.

Rambhade S, Chakarborty A, Shrivastava A, Patil UK, Rambhade A. A survey on polypharmacy and use of inappropriate medications. Toxicol Int. 2012;19(1):68–73.

Gellad WF, Grenard JL, Marcum ZA. A systematic review of barriers to medication adherence in the elderly: looking beyond cost and regime complexity. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9(1):11–23.

Zelko E, Klemenc-Ketis Z, Tusek-Bunc K. Medication adherence in elderly with polypharmacy living at home: a systematic review of existing studies. Mater Sociomed. 2016;28(2):129–32.

George J, Elliott RA, Stewart DC. A systematic review of interventions to improve medication taking in elderly patients prescribed multiple medications. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(4):307–24.

Guthrie B, Makubate B, Hernandez-Santiago V, Dreischulte T. The rising tide of polypharmacy and drug-drug interactions: population database analysis 1995-2010. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):74.

Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, Potter K, Le Couteur D, Rigby D, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827–34.

Page AT, Potter K, Clifford R, Etherton-Beer C. Deprescribing in older people. Maturitas. 2016 Sep 1;91:115–34.

Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, Kennedy J, O'Mahony DO. STOPP (screening tool of older Person’s prescriptions) and START (screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment). Consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;46(2):72–83.

Scottish Government Model of Care Polypharmacy Working Group. Polypharmacy Guidance (2nd edition). 2015. Scottish Government. http://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/publications/DC20150415polypharmacy.pdf.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management’ NICE Guideline [NG56]. 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes’NICE guideline (NG5) publication date March 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5.

Raae-Hansen C, Byrne S, O'Mahony D, Kearney PM, Sahm LJ, Cullinan S. Challenges of deprescribing in older patients with multimorbidity, from healthcare professionals' perspectives-a narrative review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(Suppl 1):16–7.

Scott IA, Anderson K, Freeman CR, Stowasser DA. First do no harm: a real need to deprescribe in older patients. Med J Aust. 2014;201(7):390–2.

Woodward MC. Deprescribing: achieving better health outcomes for older people through reducing medications. Journal Pharm Pract Res. 2003;33(4):323–8.

Kua CH, Yeo CYY, Char CWT, Tan CWY, Tan PC, Mak VS, et al. Nursing home team-care deprescribing study: a stepped-wedge randomised controlled trial protocol. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e015293.

Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch L, Caughey G. Systematic review of polypharmacy definition, assessment tools, and association with clinical outcomes. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2017;13(4):e28–9.

Mortazavi SS, Shati M, Keshtkar A, Malakouti SK, Bazargan M, Assari S. Defining polypharmacy in the elderly: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e010989.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe ‘PCNE statement on medication review’ v3.01012013 https://www.pcne.org/upload/files/150_20160504_PCNE_MedRevtypes.pdf.

Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, Bartlett G, O’Cathain A, Griffiths F, et al. Proposal: A mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews. 2011. http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/84371689/MMAT%202011%20criteria%20and%20tutorial%202011-06-29updated2014.08.21.pdf. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5tTRTc9yJ.

Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research. In: Bryman A, Burgess B, editors. Analyzing Qualitative Data. London: Routledge: Chapter 9. Routledge, London; 1994.

O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ. 2010;341(7783):1147.

Campins L, Serra-Prat M, Gózalo I, López D, Palomera E, Agustí C, et al. Randomized controlled trial of an intervention to improve drug appropriateness in community-dwelling polymedicated elderly people. Fam Pract. 2017;34(1):36–42.

Haag JD, et al. Impact of Pharmacist-Provided medication therapy management on healthcare quality and utilisation in recently discharged elderly patients. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9(5):259–68.

Basheti IA, Al-Qudah R, Obeidat NM, Bulatova NR. Home medication management review in outpatients with chronic diseases in Jordan: a randomized control trial. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(2):404–13.

Chen C, Kuo L, Cheng K, Shen W, Bai K, Wang C, et al. The effect of medication therapy management service combined with a national PharmaCloud system for polypharmacy patients. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 2016;134:109–19.

Hedegaard U, Kjeldsen LJ, Pottegård A, Henriksen JE, Lambrechtsen J, Hangaard J, et al. Improving Medication Adherence in Patients with Hypertension: A Randomized Trial. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1351–61.

Steele KM, Ruisinger JF, Bates J, Prohaska ES, Melton BL, Hipp S. Home-based comprehensive medication reviews: Pharmacist's impact on drug therapy problems in geriatric patients. Consult Pharm. 2016;31(10):598–605.

Lee VW, Choi LM, Wong WJ, Chung HW, Ng CK, Cheng FW. Pharmacist intervention in the prevention of heart failure for high-risk elderly patients in the community. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15:178.

Twigg MJ, Wright D, Barton GR, Thornley T, Kerr C. The four or more medicines (FOMM) support service: results from an evaluation of a new community pharmacy service aimed at over-65s. Int J Pharm Pract. 2015;23(6):407–14.

Tan ECK, Stewart K, Elliott RA, George J. Pharmacist consultations in general practice clinics: the pharmacists in practice study (PIPS). Res Social Adm Pharm. 2014;10(4):623–32.

Hatah E, Tordoff J, Duffull SB, Cameron C, Braund R. Retrospective examination of selected outcomes of medicines use review (MUR) services in New Zealand. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36(3):503–12.

Roth MT, Ivey JL, Esserman DA, Crisp G, Kurz J, Weinberger M. Individualized medication assessment and planning: optimizing medication use in older adults in the primary care setting. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(8):787–97.

Vinks THAM, Egberts TCG, de Lange TM, de Koning FHP. Pharmacist-based medication review reduces potential drug-related problems in the elderly: the SMOG controlled trial. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(2):123–33.

Sturgess I, McElnay J, Hughes C, Crealey G. Community pharmacy based provision of pharmaceutical care to older patients. Pharm World Sci. 2003;25(5):218–26.

Grymonpre RE, Williamson DA, Montgomery PR. Impact of a pharmaceutical care model for non-institutionalised elderly: results of a randomised, controlled trial. Int J Pharm Pract. 2001;9(4):235–41.

Raynor DK, Nicolson M, Nunney J, Petty D, Vail A, Davies L. The development and evaluation of an extended adherence support programme by community pharmacists for elderly patients at home. Int J Pharm Pract. 2000;8(3):157–64.

Lowe CJ, Raynor DK, Purvis J, Farrin A, Hudson J. Effects of a medicine review and education programme for older people in general practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;50(2):172–5.

Hanlon JT, Weinberger M, Samsa GP, Schmader KE, Uttech KM, Lewis IK, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a clinical pharmacist intervention to improve inappropriate prescribing in elderly outpatients with polypharmacy. Am J Med. 1996;100(4):428–37.

Fiβ T, Meinke-Franze C, van den Berg N, Hoffmann W. Effects of a three party healthcare network on the incidence levels of drug related problems. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(5):763–71.

Jäger C, Freund T, Steinhaeuser J, Stock C, Krisam J, Kaufmann-Kolle P, et al. Impact of a tailored program on the implementation of evidence-based recommendations for multimorbid patients with polypharmacy in primary care practices-results of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):8.

Griffiths R, Johnson M, Langdon R, Piper M. A nursing intervention for the quality use of medicines by elderly community clients. Int J Nurs Pract. 2004;10(4):166–76.

Beer C, Loh P, Peng YG, Potter K, Millar A. A pilot randomized controlled trial of deprescribing. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2011;2(2):37–43.

Messerli BE, Vriends N, Hersberger KE. Impact of a community pharmacist-led medication review on medicines use in patients on polypharmacy - a prospective randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:145.

de Wit L, Fenenga C, Giammarchi C, di Furia L, Hutter I, de Winter A, et al. Community-based initiatives improving critical health literacy: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative evidence. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:40.

Marcum ZA, Hanlon JT, Murray MD. Improving medication adherence and health outcomes in older adults: an evidence-based review of randomized controlled trials. Drugs Aging. 2017;34(3):191–201.

Health and Care Professions Council. Standards for prescribing. No date. https://www.hcpc-uk.org/resources/standards/standards-for-prescribing/.

Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, Schwartz D, Etherton-Beer CD. The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016 Sep 1;82(3):583–623.

Tan EC, Sluggett JK, Johnell K, Onder G, Elseviers M, Morin L, et al. Research priorities for optimizing geriatric pharmacotherapy: an international consensus. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(3):193–9.

Thillainadesan J, Gnjidic D, Green S, Hilmer SN. Impact of deprescribing interventions in older hospitalised patients on prescribing and clinical outcomes: a systematic review of randomised trials. Drugs Aging. 2018;35(4):303–19.

Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG, Kouladjian L, Hilmer SN. Deprescribing trials: methods to reduce polypharmacy and the impact on prescribing and clinical outcomes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):237–53.

Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, Schwartz D, Etherton-Beer CD. The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J of Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(3):583–623.

Thomas R, Huntley AL, Mann M, Huws D, Elywn G, Paranjothy S, et al. Pharmacist-led interventions to reduce unplanned admissions for older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Age Ageing. 2014;43(2):174–87.

Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: A systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30:793–807.

Zermansky AG, Alldred DP, Petty DR, Raynor DK, Freemantle N, Eastaugh J, et al. Clinical medication review by a pharmacist of elderly people living in care homes-a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2006;35(6):586–91.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Andrew Adams, Clinical Pharmacist, Northern General Hospital, Sheffield, for his contribution to the initial stages of the review process.

Funding

This work was undertaken by arrangement between Sheffield Hallam University and Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and did not receive funding from any funding agency.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials are available on request from the corresponding author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SFD led the project, and was responsible for the review with substantial contribution to conception, design, drafting and completion of the manuscript. JU made substantial contribution to the conception and design, was involved in drafting the manuscript and contributed critically for important intellectual content. DH made substantial contributions to the design and acquisition of data and analysis and contributed to drafting of the manuscript, AA contributed to the design and acquisition of data and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. SA made a substantial contribution to the design and acquisition of data and was involved in the drafting of the manuscript. SFD, JU, DH, AA and SA give final approval for the final version and take full responsibility for the content and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, associated with accuracy and integrity. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

N/A

Consent for publication

Non applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Appendix 1. Search terms for the study. (DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ulley, J., Harrop, D., Ali, A. et al. Deprescribing interventions and their impact on medication adherence in community-dwelling older adults with polypharmacy: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 19, 15 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1031-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1031-4