Abstract

Trichinella spiralis is a zoonotic nematode and food borne parasite and infection with T. spiralis leads to suppression of the host immune response and other immunopathologies. Alternative activated macrophages (M2) as well as Treg cells, a target for immunomodulation by the helminth parasite, play a critical role in initiating and modulating the host immune response to parasite. The precise mechanism by which helminths modulate host immune response is not fully understood. To determine the functions of parasite-induced M2 macrophages, we compared the effects of M1 and M2 macrophages obtained from Trichinella spiralis-infected mice with those of T. spiralis excretory/secretory (ES) protein-treated macrophages on experimental intestinal inflammation and allergic airway inflammation. T. spiralis infection induced M2 macrophage polarization by increasing the expression of CD206, ARG1, and Fizz2. In a single application, we introduced macrophages obtained from T. spiralis-infected mice and T. spiralis ES protein-treated macrophages into mice tail veins before the induction of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis, ovalbumin (OVA)-alum sensitization, and OVA challenge. Colitis severity was assessed by determining the severity of colitis symptoms, colon length, histopathologic parameters, and Th1-related inflammatory cytokine levels. Compared with the DSS-colitis group, T. spiralis-infected mice and T. spiralis ES protein-treated macrophages showed significantly lower disease activity index (DAI) at sacrifice and smaller reductions of body weight and proinflammatory cytokine level. The severity of allergic airway inflammation was assessed by determining the severity of symptoms of inflammation, airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), differential cell counts, histopathologic parameters, and levels of Th2-related inflammatory cytokines. Severe allergic airway inflammation was induced after OVA-alum sensitization and OVA challenge, which significantly increased Th2-related cytokine levels, eosinophil infiltration, and goblet cell hyperplasia in the lung. However, these severe allergic symptoms were significantly decreased in T. spiralis-infected mice and T. spiralis ES protein-treated macrophages. Helminth infection and helminth ES proteins induce M2 macrophages. Adoptive transfer of macrophages obtained from helminth-infected mice and helminth ES protein-activated macrophages is an effective treatment for preventing and treating airway allergy in mice and is promising as a therapeutic for treating inflammatory diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Macrophage activation can be generally divided into two distinct categories: classically activated macrophages (M1) and alternatively activated macrophages (AAM, M2). After infection with bacteria or viruses, Th1 cytokine interferon (IFN)-gamma and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) polarize macrophages toward the M1 phenotype, which induces macrophages to upregulate interleukin (IL)-12 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expressions. In contrast, M2 macrophages are driven by the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. M2 cells also express high levels of arginase-1 (ARG1), mannose receptor, and resistance-like molecule-α1,2,3,4.

In addition, M2 macrophages can be further subdivided into the M2a, M2b, and M2c categories based on gene expression profiles. The common characteristic of all three subpopulations is the low production of IL-12 accompanied by high IL-10 production. One of their signatures is the production of enzyme Arg1, which depletes L-arginine to suppress T-cell responses and deprive iNOS of its substrate5,6. M2a macrophages are related to the Th2 immune response such as that against parasites, and they are known to be profibrotic. They secrete profibrotic factores such as insulin- like growth factor(IGF), TGF- β and fibronectin to contribute to tissue repair7,8,9. These cells also express high levels of IL-4R, FcεR, Dectin-1, CD163, CD206, CD209, and other scavenger receptors. M2b macrophages are induced upon combine exposure to IC and TLR agonist or by IL-1R agonists and express high level s of TNF superfamily 14 and CCL1. These cells express and secrete high levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 and low levels of IL-22, which is the function al converse of M1 macrophages. They also produce IL-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α Base on the expression of cytokines and molecules, M2b macrophages regulate the immune response and the inflammatory reaction8,10,11,12. M2c induced by IL-10 via activating signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) through IL-10R and strongly exhibit anti -inflammatory activities by releasing substantial amounts of IL-10 and profibrotic activity secreting high levels of TGF- β7,8,13.

The regulation of macrophage function involves the activation of various transcriptional pathway-related molecules including members of the interferon-regulatory factor (IRF) family, signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) families, and nuclear factor-κB14,15,16,17. A recent study described a role for IRFs in macrophage polarization18,19. Many studies have demonstrated that IRF5 promotes inflammatory macrophage polarization in LPS-stimulated macrophages20,21. Additionally, LPS signaling through TLR4 pathways induces the activation and phosphorylation of the transcription factor IRF3, which regulates M1 gene expression22,23. In addition, numerous studies have shown that IRF4 promotes M2 macrophage polarization, and that expression of ARG1 was induced in IL-4-stimulated macrophages24,25.

For many studies, there is much interest in whether helminth-associated immune regulation may alleviate disease such as allergy and IBD26,27. Many helminth species have been showed to modulate allergic responses, most notably the intestinal nematode H . polygyrus, which suppresses airway hyperresponsiveness, lung histopathology, eosinophil recruitment, and Th2 cytokines in alum-sensitized models and IgE and anaphylaxis in a peanut allergy model28,29,30,31. Schistosome infections, egg or adult worm extract suppressed Th1/17 responses and pathology and induced the Th2 cytokines IL-10 and TGF- β32,33,34. Also, our previous study demonstrated that Trichinella spiralis infection derived Treg cells were the key cells mediating the amelioration of allergic airway inflammation and DSS-induced colitis in mice35,36. Infection with parasites such as Brugia malayi and Schistosoma mansoni triggers M2 macrophages37,38,39,40,41. A previous study reported that T. spiralis infection induced YM1-expressing M2 macrophages, but the function of these cells remains unclear42,43,44. Evidence of immune modulation of macrophage derives from cancer models in which tumor-associated macrophages have been reported to both promote tumor survival and suppress tumor immunity. Several studies have investigated the regulatory role of macrophages in inhibiting inflammation, including models of spinal cord injury, kidney disease, and multiple sclerosis. Although these findings clearly indicate the important role of macrophages in the alleviation of inflammation45,46,47,48,49.

In this study, the functional characteristics of macrophages induced by T. spiralis infection in the regulation of DSS-colitis and allergic airway inflammation were examined. The ability of T. spiralis ES proteins to modulate macrophage activation in vitro was determined by detecting the production of the effector molecules iNOS, Arg1, and cytokines. In addition, the effects of ES proteins in a dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-colitis model and an allergic airway inflammation model were investigated.

Results

T. spiralis infection induced M2 macrophage polarization

To determine which type of macrophage was activated during T. spiralis infection, the expression levels of M1 and M2 marker including CD11c. iNOS (M1 marker), and CD206, Argninase 1 (Arg1) (M2 marker) were evaluated in macrophages obtained from peritoneium of T. spiralis-infected mice at 2 weeks post infection (PI). The expression of M2 markers including CD206 and ARG 1 was significantly increased in of T. spiralis-infected mice compared to control mice at 2 weeks (PI) Whereas, the expression of M1 markers including CD11c and iNOS was not significant (Fig. 1A–D).

Expression of M1 and M2 markers on peritoneal macrophage. Expression levels of M1 (CD11c (A), iNOS (B) and M2 (CD206 (C), Arg1(D)) markers were analyzed in macrophages from the peritoneal macrophages (C) of T. spiralis-infected or control mice (2 weeks P.I) by using FACS canto II. After staining, the expressions of CD11c, iNOS, CD206 and Arg1 were plotted. After staining, the macrophages were firstly gated with F4/80 -positive cells and the percentage of CD11c, iNOS, CD206 and Arg1 positive cells calculated using FACS analysis. The graphs show the mean of the fluorescence intensity experimental group in the right panel. Statistical analysis was performed with Student’t t-test. (***p < 0.001; n = 3 mice/group; these results are representative of three independent experiments).

As a result, T. spiralis infection induced M2 macrophage polarization by inducing the expression of ARG1 and CD206 at 2 weeks (PI).

Adoptive transfer of peritoneal macrophages from T. spiralis-infected mice inhibited DSS-induced colitis

To ascertain whether T. spiralis-induced macrophages can prevent intestinal inflammation in the DSS-colitis model, the mice were injected with peritoneal macrophages isolated from T. spiralis-infected mice and assessed for intestinal inflammation responses after DSS administration. Figure Fig. 2A,B shows the experimental protocol of macrophage adoptive transfer and the DSS-colitis model. DSS administration to mice induced an acute histological change in the colon and pronounced weight loss. DSS-treated mice exhibited significant colon shortening, but the large intestines of the peritoneal macrophage-injected mice were longer than those of DSS-treated mice (6.53 ± 0.11 vs . 7.4 ± 0.1, p < 0.001; Fig. 3A,B). DSS-treated mice showed pronounced weight loss, with diarrhea and bloody stool and increased DAI from days 3 to 8. However, these clinical symptoms of DSS-treated mice after peritoneal macrophage injection were less minimized or profound compared to those of the peritoneal macrophage non-injected group at sacrifice (8 ± 1.15 vs. 6.75 ± 0.5, p < 0.05; Fig. 3C). Figure 3D shows the histological changes in the large intestine after DSS treatment. The epithelium and submucosa of the colons in DSS-untreated mice were maintained. However, the submucosa of the colon in DSS-treated mice showed immune cell infiltration, villi destruction, and ulcerative mucosa in the epithelium. While most of the epithelium remained intact, ulcerative lesions and inflammatory cell recruitment were rarely detected, and the degree of colon destruction was lower in DSS-treated mice after peritoneal macrophage injection than in DSS-treated mice. To characterize the manner in which peritoneal macrophages of T. spiralis-infected mice affect cytokine production from the MLN, the production of various cytokines was measured by ELISA. Peritoneal macrophage injection significantly reduced the secretion of IL-1β (314 ± 24.2 vs. 243.3 ± 15.27, p < 0.05; Fig. 3E), whereas the reduction of IFN-γ was not significant (data not shown). Furthermore, IL-10 secretion significantly increased (1757.5 ± 155.2 vs. 2082.5 ± 303.04, p < 0.05; Fig. 3F). These results indicate that T. spiralis-induced macrophages can inhibit the production of proinflammatory cytokines, which is consistent with the ameliorated DSS-induced colitis observed in T. spiralis-induced macrophage-transferred mice.

Experimental protocol of macrophage adoptive transfer and DSS-induced colitis model. Colitis was induced via DSS administration according to the experimental protocols in Methods (A). First, peritoneal macrophages were isolated from T. spiralis-infected mice at 2 weeks post-infection. The cells were stained with CellTracker CM-DiI (Life Technologies). The mice were injected intravenously with 5 × 105 cells before the first DSS administration [day 0] (B). Second, BMDMs were isolated from C57BL/6 mice and treated with ES proteins (1 μg/mL) for 24 h. The mice were injected intravenously with 5 × 105 cells before the first DSS administration [day 0] (C).

Adoptive transfer of peritoneal macrophages from T. spiralis-infected mice inhibited DSS-induced colitis. After sacrificing the mice, colon length was measured (A,B). The percentage weight loss, changes in stool states including consistency, and blood presence in stools of mice were examined daily during the experimental period and represented as DAI. The DAI standard is shown in Table 2. The DAI results are shown in (C). The large intestines were isolated from mice, rolled up, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with H&E, and examined for histopathological changes under a microscope (D). Arrows indicate sub-mucosal thickening and immune cell infiltration, characteristic of colitis. The immune cells of MLN were incubated for 72 h with anti-CD3 antibody (0.5 μg/mL) for T-cell stimulation. After incubation, cytokine production in the supernatant was determined by ELISA (E, F). Large intestine sections from mice receiving peritoneal macrophages (CM-Dil, red) were immunofluorescently stained for cell nuclei (DAPI, blue). Representative pictures are shown. White bar: 100 μm (G) Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA ((*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001; n = 3 to 5 mice/group; these results are representative of three independent experiments).

Transferred peritoneal macrophages infiltrate the site of inflammation

Peritoneal macrophages of DSS-colitis induction were stained with Cm-DiI fluorescent carbocyanite. Interestingly, peritoneal macrophages in the large intestine were detected in peritoneal macrophage-transferred mice. In mice without DSS administration, few peritoneal macrophages were detected in the large intestine. However, numerous peritoneal macrophages were detected in DSS-colitis induced mice (Fig. 3G). These data reveal that macrophages induced with T. spiralis can regulate intestinal inflammation via migration to inflamed tissues, activation, and regulation.

Adoptive transfer of peritoneal macrophages from T. spiralis-infected mice inhibited airway inflammation

To evaluate whether T. spiralis-induced macrophages can inhibit airway inflammation in the OVA-alum model, mice were injected with peritoneal macrophages isolated from T. spiralis-infected mice and intestinal inflammation responses were examined after OVA-alum induction. Figure 4 and B shows the experimental protocol of macrophage adoptive transfer and airway inflammation. PenH was used an indicator of lung function. Mice were challenged with increasing methacholine aerosols (0, 12.5, 25 and 50 mg/ml). Methacholine dose-dependently increased the value of PenH in the OVA-alum induction group. Pretreatment with T. spiralis-induced macrophages decreased the PenH value in OVA-alum induction (5.9 ± 1.2 vs. 4.6 ± 0.7, p < 0.05; Fig. 5A).

Experimental protocol of macrophage adoptive transfer and airway inflammation induction model. Airway inflammation was induced via OVA-alum administration according to the protocols in Methods (A). First, peritoneal macrophages were isolated from T. spiralis-infected mice at 2 weeks post-infection. The cells were stained with CellTracker CM-DiI (Life Technologies). The mice were injected intravenously with 5 × 105 cells before the first OVA-alum sensitization [day 0] (B). Second, BMDMs were isolated from C57BL/6 mice and treated with ES proteins (1 μg/mL) for 24 h. The mice were injected intravenously with 5 × 105 cells before OVA-alum sensitization [day 0] (C).

Amelioration of airway inflammation by peritoneal macrophage transfer before asthma induction. PenH was determined at baseline and after administration with increasing doses of aerosolized methacholine (0, 12.5, 25, 50 mg/mL) at day 24 (A). All animals were sacrificed on day 25. After sacrificing the mice, the number of differential immune cells in the BALF was counted after Diff-Quik staining (B). The lungs were isolated from mice, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with H&E, and examined for histopathological changes under a microscope. Cytokine production was measured in lymphocytes isolated from the BALF (D,E) and LLN (F,G) by ELISA. Lung sections from mice receiving peritoneal macrophages (CM-DiI, red) were immunofluorescently stained for cell nuclei (DAPI, blue). Representative pictures are shown (H). White bar: 100 μm. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA and Student’t t-test (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001; n = 3–5 mice/group; these results are representative of three independent experiments).

Different counts of cells in the BALF revealed that pretreatment with T. spiralis-induced macrophages before OVA sensitization and challenge significantly decreased the number of total cells and eosinophils in the BALF compared to that in mice treated with OVA only (50,000 ± 160 vs. 41,000 ± 300, p < 0.05, 25,000 ± 450 vs. 12,000 ± 210, p < 0.05, respectively; Fig. 5B). After pretreatment with T. spiralis-induced macrophages before OVA treatment, tissue inflammation after OVA challenge markedly decreased, and significantly less peribronchial and perivascular cellular infiltration was observed compared to that in OVA-treated mice (Fig. 5C).

To characterize the manner in which peritoneal macrophages of T. spiralis-infected mice affect cytokine production from BALF and LLN, the production of various cytokines was measured by ELISA. In BALF, peritoneal macrophage injection resulted in significant reductions of Th2 cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-5 (155 ± 21.2 vs. 86.6 ± 15.27, p < 0.05, 111.3 ± 7.5 vs. 83.3 ± 9.1, p < 0.01, respectively; Fig. 5D,E). In the LLN, peritoneal macrophage injection significantly reduced the secretion of Th2 cytokines such as IL-4 (230 ± 26.4 vs. 167.5 ± 30.9, p < 0.05; Fig. 5F), whereas the concentrations of TGF-β significantly increased (320 ± 26.4 vs. 376 ± 20.8, p < 0.05; Fig. 5G). Thus, these results indicate that T. spiralis-induced macrophages inhibit the production of Th2 cytokines, which is consistent with the ameliorated airway inflammation observed in T. spiralis-induced macrophage-transferred mice.

Transferred peritoneal macrophages infiltrate the site of allergic airway inflammation

Peritoneal macrophages were stained with Cm-DiI fluorescent carbocyanite before airway inflammation. Interestingly, peritoneal macrophages in the lung were detected in peritoneal macrophage-transferred mice. Numerous peritoneal macrophages were detected in the lung of airway inflammation–induced mice (Fig. 5H). These data demonstrate that T. spiralis-induced macrophages can regulate airway allergic responses by migrating to inflamed tissues.

T. spiralis ES proteins induced M2 macrophages

To investigate the effect of ES proteins on macrophage activation, we evaluated the mRNA expression of genes in BMDM cultured with or without ES proteins for 24 h. Cells were left untreated or were treated with ES proteins (1 μg/mL) for 24 h before stimulation with LPS (100 ng/mL) or IL-4 (20 ng/mL) for 1 h. As shown in Fig. 6A, ES proteins suppressed the mRNA level of M1 markers in LPS-stimulated macrophages (M1). Additionally, ES proteins alone increased the mRNA level of M2 markers in BMDM (2.12 ± 0.45 vs. 3.6 ± 0.24, p < 0.01; Fig. 6B).

Effects of ES proteins from T. spiralis on M1 and M2 marker expressions in peritoneal macrophages. Primary macrophages were derived from cells in the peritoneal cavity and were cultured for 24 h in media. The gene expression levels of M1 and M2 markers were analyzed via real-time PCR (A–G). CON, cell culture medium; LPS, LPS (100 μg/mL) treatment; ES, ES proteins (1 μg/mL) treatment; LPS + ES, LPS and ES treatment; IL-4, IL-4 (20 ng/mL) treatment; IL-4+ ES, IL-4 and ES treatment. LPS and IL-4 served as M1 and M2 positive control. The cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies specific for phosphorylated forms of IRF3 and total forms of IRF4 and ARG1. The blot was re-probed with an antibody to β-actin as a control. These figures are representative of three independent experiments (areas of the detected bands were determined and compared by using Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) Statistical analysis was performed with Student’t t-test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; n = 3–5 mice/group; these results are representative of three independent experiments).

To distinguish classical from alternative macrophage activation in BMDM, the gene expression levels of markers were examined. The expression of NOS2 (nitric oxide synthase) increased in LPS-treated macrophages (1.01 ± 0.219 vs. 1.6 ± 0.3, p < 0.001; Fig. 6C). Treatment with ES proteins significantly decreased expression of NOS2 compared to that in the control (1.01 ± 0.219 vs. 0.6 ± 0.0.32, p < 0.05; Fig. 6C). The mRNA expression of Il4ra (IL-4Rα) observed in IL-4-treated BMDM was significantly increased (1.01 ± 0.219 vs. 4.136 ± 0.059, p < 0.001). Treatment with ES proteins remarkably increased this expression (1.01 ± 0.219 vs. 5.95 ± 0.059, p < 0.001; Fig. 6D). The expressions of these two markers were markedly increased in ES protein-treated macrophages, suggesting alternative activation of macrophages.

Upon LPS stimulation of TLR4, a range of metabolic changes occurs in macrophages. LPS activates mTOR, thereby increasing translation of mRNA with 5′-TOP sequences, including hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α mRNA; subsequently, HIF-1α increases the expression of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1)50. In this study, the expressions of genes related to metabolic regulation were measured (Fig. 6E–G). Treatment of BMDM with LPS increased the expression of GLUT1 and HIF1-α; however, IL-4 and ES protein treatments did not affect the expression of these two genes. In addition, numerous studies have indicated that strong STAT6 activation results in M2 macrophage polarization, which is associated with immune suppression51. The mRNA expression of STAT6 was significantly increased in the presence of IL-4 compared to that in the control. Interestingly, treatment with ES proteins significantly increased the expression of STAT6 by more than that following treatment with IL-4 (1 ± 0.165 vs. 1.89 ± 0.4, p < 0.05).

To determine whether phosphorylation of IRF3 were related to the suppression of LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokines by ES proteins, the phosphorylation of IRF3 were examined in LPS-induced macrophages by western blotting (Fig. 6H). The results showed that the levels of IRF3 phosphorylation were remarkably increased by LPS stimulation. However, treatment with ES proteins dramatically decreased phosphorylation (ratio of phosphorylated IRF3 to the total IRF3 (pIRF3:IRF3) 0.92 vs 0.57). Additionally, the expression levels of IRF4 were greatly increased by IL-4 stimulation. Treatment with ES proteins considerably increased the expression of IRF4. The expression of ARG1 was slightly increased by IL-4 stimulation. Treatment with ES proteins slightly increased the expression of ARG1 compared to that in untreated macrophages. The results demonstrate that ES protein treatment increased IRF4 and STAT6 expression related to M2 macrophages polarization.

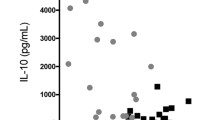

Naïve T cells with BMDMs stimulated by ES proteins induced anti-inflammatory cytokines

ES protein-activated BMDMs from mice were co-cultivated with naïve T cells (CD4+CD25−CD62L+ T cells) for 72 h. After co-culture, the expression levels of cytokines in the culture supernatant were evaluated by ELISA (Fig. 7). Naïve T cells with BMDMs stimulated with ES proteins as well as IL-4 induced the production of IL-10 and TGF-β. Naïve T cells co-cultivated with ES protein stimulated macrophages did not affect the production of IFN-γ and IL-17A (data not shown). The production of Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-5, was strongly suppressed in the supernatant of naive T cells with BMDMs stimulated with ES proteins. As a result, naive T cells with BMDMs stimulated with ES proteins increased the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as TGF-β and IL-10, whereas the production of Th2 cytokines was suppressed.

Naïve T cells with BMDM stimulated with ES proteins induced anti-inflammatory cytokines, not Th2 cytokines . Naïve T cells were cultured with BMDM stimulated by ES proteins, IL-4, or LPS or with non-stimulated BMDMs from mice for 3 days. Subsequently, the cells were incubated in the presence of anti-CD3 antibody. Expression levels of cytokines were determined in cultured supernatant by ELISA (Non: naïve T cells with non-stimulated BMDMs. LPS: naïve T cells with BMDMs stimulated with LPS. IL-4: naïve T cells with BMDMs stimulated with IL-4. ES: naïve T cells with BMDMs stimulated with ES proteins). LPS and IL-4 served as M1 and M2 positive control. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; n = 4, these results are representative of three independent experiments).

Adoptive transfer of T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophages inhibited DSS-induced colitis

To evaluate whether T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophages can prevent intestinal inflammation in a DSS-colitis model, the mice were injected with T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophages and intestinal inflammation responses were evaluated after DSS administration. Figure 2A,C show the experimental protocol for macrophage adoptive transfer and the DSS-colitis model. DSS administration to mice induced acute inflammation in the colon and caused marked weight loss and bloody diarrhea. DSS-treated mice exhibited significant shortening of the colon (8.26 ± 0.4 vs. 5.93 ± 0.4, p < 0.01), but the large intestines of T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophage-injected mice were longer than those of DSS-treated mice (5.93 ± 0.4 vs. 7.02 ± 0.27, p < 0.05; Fig. 8A,B). DSS-treated mice showed continuing weight loss, with diarrhea and blood in the stool, and increased DAI scores from 1 to 8 days. However, these symptoms in DSS-treated mice after T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophage injection were minimized compared to those in the T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophage non-injected group (8.6 ± 0.5 vs. 7.4 ± 0.5, p < 0.05; Fig. 8C). Figure 8D shows the histological changes in the large intestine after DSS treatment. The epithelium and a sub-mucosal layer of the colons of DSS-untreated mice remained intact. However, the sub-mucosal layers of the colon in DSS-treated mice showed villi destruction and inflammatory cell infiltration as well as ulcerative mucosa in the epithelium. While most of the epithelium was intact, ulcerative lesions and inflammatory cell recruitment were rarely detected, and the degree of colon destruction was lower in DSS-treated mice after T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophage injection than that in DSS-treated mice. To characterize how T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophages affect cytokine production in the MLN, various cytokines were measured by ELISA. T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophage injection resulted in a significant reduction in IL-1β secretion compared to that in the DSS-treated group (DSS-treated only; 535.4 ± 144.7 vs. 388.6 ± 25.7, p < 0.05; Fig. 8E) but IL-1β showed no significant reduction (data not shown). Furthermore, the secretion of IL-10 and TGF-β significantly increased (1828.6 ± 4.89 vs. 1195.9 ± 109.7, p < 0.05; 995.9 ± 4.89 vs. 1195.9 ± 109.7, p < 0.05, respectively; Fig. 8F,G). These results indicate that T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophages inhibit the production of proinflammatory cytokines, which is consistent with the ameliorated DSS-induced colitis observed in T. spiralis-induced macrophage-transferred mice.

Adoptive transfer of T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophages inhibited DSS-induced colitis. After sacrificing the mice, colon length was measured (A,B). The percentage of weight loss, changes in stool states including consistency, and blood presence in the stool of mice were determined daily during the experimental period and represented as DAI. The DAI standard is shown in Table 2. The DAI results are shown in (C). The large intestines were isolated from mice, rolled up, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with H&E, and their histopathological changes were examined under a microscope (D). Arrows indicate sub-mucosal thickening and immune cell infiltration, characteristic of colitis. The immune cells of MLN were incubated for 72 h with anti-CD3 antibody (0.5 μg/mL) for T-cell stimulation. After incubation, cytokine production levels in the supernatant were determined by ELISA (E–G). Representative pictures are shown. White bar: 100 μm (H) Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA. (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001; n = 3–5 mice/group; these results are representative of three independent experiments).

Adoptive transfer of T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophages inhibited airway inflammation

To evaluate whether T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophages can prevent airway inflammation in the OVA-alum model, mice injected with peritoneal macrophages isolated from T. spiralis-infected mice were examined for intestinal inflammation responses after OVA-alum induction. Figure 4A,C show the experimental protocol of macrophage adoptive transfer and the airway inflammation. To assess lung function, mice were challenged with increasing methacholine aerosols (0, 12.5, 25, and 50 mg/mL). Methacholine dose-dependently increased the value of PenH in the OVA-alum induction. Pretreatment with T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophages decreased the value of PenH in OVA-alum induced mice (7.37 ± 1.2 vs. 4.2 ± 1.2, p < 0.01; Fig. 9A). Differential cell counts in the BALF revealed that pretreatment of T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophages before OVA sensitization and challenge significantly decreased the numbers of total cells and eosinophils in the BALF compared to that in OVA-treated mice (60,000 ± 800 vs. 35,000 ± 420, p < 0.01; 30,000 ± 430 vs. 12,000 ± 260, p < 0.05, respectively; Fig. 9B). After pretreatment of T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophages before OVA treatment, tissue inflammation after OVA challenge was greatly reduced with significantly less peribronchial and perivascular cellular infiltration compared to that in OVA-treated mice and non-treated macrophage-transferred mice.

Amelioration of airway inflammation by T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophage transfer before asthma induction. PenH was evaluated at baseline and after administration with increasing doses of aerosolized methacholine (0, 12.5, 25, and 50 mg/mL) at day 24 (A). All animals were sacrificed on day 25. After sacrificing the mice, the numbers of differential immune cells in the BALF were counted after Diff-Quik staining (B). The lungs were isolated from mice, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with H&E, and then examined for histopathological changes under a microscope. Cytokine production was measured in lymphocytes isolated from BALF (D–F) and LLN (G) by ELISA. White bar: 100 μm. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001; n = 3–5 mice/group; these results are representative of independent experiments).

Additionally, pretreatment with T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophages suppressed mucus production and hypertrophy of goblets cells compared to that in OVA-treated mice (Fig. 9C). To characterize how T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophages affect cytokine production from the BALF and LLN, productions of various cytokines were measured by ELISA. In the BALF, T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophage injection significantly reduced the secretion of Th2 cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-5, whereas the secretion of IL-13 showed no significant reduction (74 ± 10.5 vs. 91.6 ± 7.6, p < 0.01; 106.6 ± 1.1 vs. 79.4 ± 5.9, p < 0.001; 497.5 ± 68.9 vs. 630 ± 120.4, p < 0.05, respectively; Fig. 9D–F). Furthermore, the secretions of TGF-β were significantly increased. In the LLN, T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophage injection significantly reduced the secretion of Th2 cytokines such as IL-5 (102.5 ± 3.53 vs. 68.5 ± 13.02, p < 0.05; Fig. 9G), whereas the reductions in IL-4 secretion were not significant (data not shown). These results indicate that T. spiralis-induced macrophages inhibit the production of Th2 cytokines, which is consistent with the ameliorated airway inflammation observed in T. spiralis ES protein-induced macrophage-transferred mice.

Discussion

During helminth infections, M2 macrophages, as well as Treg cells, are expanded. These cells have been shown to induce Treg cell differentiation52,53 and, through upregulation of ARG1, have a role in tissue repair and important immune regulation by competing for L-arginine and generating proline54,55. Many study reveals an important role of YM1+ M2 macrophages in allergic lung inflammation. M2 macrophages are present in high numbers in lungs of humans and mice with allergic lung inflammation56,57,58,59, but their role in this disease remains controversial.

Previous study reported that M1 and M2 macrophages play opposing roles in DSS-induced colitis60. M1 macrophages comprise to the pathogenesis of DSS-induced colitis by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines and causing tissue damage61. In contrast, similar to our observations showing that M2 macrophages contribute to the resolution of DSS-induced colitis primarily by expressing high levels of IL-10, but low levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines60,62,63. It has been reported chemerin aggravates DSS- induced colitis by suppresin g M2 macrophage polarization64. The activation of these regulatory cells during helminth infection may be responsible for the bystander suppression of immune diseases, which has been observed in several studies65. The purpose of this study was to determine the role of macrophages induced by T. spiralis . We investigated the relationship between macrophages induced by T. spiralis infection and immune disease. First, the M2 macrophage population, as well as that of Treg cells, increased during T. spiralis infection (Fig. 3). T. spiralis-induced macrophage-transferred mice reduced the symptoms and inflammation in DSS-colitis and airway inflammation by suppressing the increased levels of Th1 and Th2 cytokines, respectively (Figs 4 and 5).

Helminths have evolved to produce molecules that enhance immune regulation. For example, the intestinal nematode parasite Heligmosomoides polygyrus bakeri secretes a TGF-β-like ligand that differentiates Treg cells66,67,68. Given the recent advances in understanding ES proteins in helminths, we investigated the immune modulation action of ES proteins in macrophages. Pretreatment of BMDM with T. spiralis ES proteins significantly suppressed the expression of iNOS in LPS-induced macrophages (M1). However, pretreatment of macrophages with T. spiralis ES proteins significantly induced the expression of ARG1 in IL-4-induced macrophages (M2) (Fig. 6). These results suggest that ES proteins inhibit M1 marker expression in LPS-stimulated macrophages and induce M2 marker expression in IL-4-stimulated macrophages. The suppression of proinflammatory activity is involved in a reduction in the severity of inflammatory diseases in T. spiralis infection. These results coincide with previous results in which T. spiralis infection suppressed host iNOS expression69,70,71,72. Additionally, T. spiralis ES products regulate proinflammatory cytokines73,74,75. Macrophages treated with ES proteins induced the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β. Similar to that observed in this study, Broadhurst et al. reported that M2 macrophages promote Foxp3+ Treg cell differentiation by increasing IL-10 and TGF-β52,76. IRFs were originally found to regulate type I IFN expression and signal pathways. However, a recent study showed that IRF regulates dendritic cells and macrophages77. Particularly, IRF4 was shown to regulate M2 macrophage polarization in response to parasites or chitin in the fungal cell wall78,79.

T. spiralis ES proteins promoted IRF4 and M2-related metabolic regulation via STAT6 signaling (Fig. 6). ES products of Fasciola hepatica were previously reported to induce M2-like phenotypes by increasing the expression of Arg-180,81. Furthermore, similar to our results, YM1-expressing M2 induction has been reported in T. spiralis-infected mice, but the function of these cells is not established42,43. To directly determine the role of ES protein-induced macrophages, macrophages treated with ES proteins were prepared and transferred into mice to prepare a mouse disease model. The results show that M2 macrophages induced by T. spiralis ameliorated the symptoms of DSS-colitis and inhibited the Th1 response (Fig. 8). Additionally, M2 macrophages induced by T. spiralis reduced the symptoms of OVA-induced allergic airway inflammation and suppressed allergic Th2 responses (Fig. 9). Our data correspond well with those of Leung et al., who reported that M2 macrophages inhibited colitis in a dinitrobenzene sulfonic murine colitis model82,83. ARG1 was originally hypothesized to promote Th2-driven inflammation84,85,86. In contrast, there are some reports indicating that ARG1-expressing macrophages inhibit chronic Th2 responses. It has also been shown that ARG1-expressing macrophages suppress Th2 inflammation and fibrosis in Schistosoma mansoni infection87,88. How do M2 macrophages regulate air way inflammation? Are they activated in the peritoneum, at peripherally located lymph nodes, or at inflammatory sites? In this study, although we could not directly evaluate M2 macrophages cell population in the lung by FACS analysis because we have technical limitation such for preparation. However, we observed many CM-DII stained cells (injected cell) around inflammation sites in the airways, but it was difficult to detect cells in the absence of inflammation (Figs 4 and 5). M2 macrophages may regulate their recruitment and activation at sites of inflammation. We also did not specifically examine the cytokine/chemokine expression by macrophages in this study, but the data suggest that recruited macrophages in inflamed tissues actively contributed to the inhibiting inflammation. Taylor et al., reported that rodent filarial nematode Litomosoides sigmodontis infection of the pleural cavity, M2 macrophages are recruited to both the draining lymph nodes and the site of infection and suppress T cell responses at both sites89.

Indeed, there is currently controversy regarding whether M2 macrophages are effector or regulatory populations in vivo. The homeostatic role of M2 macrophages also extends to protecting the host from potentially harmful inflammation. A broader question yet to be resolved is whether M2 macrophages mediate primarily immunity rather than regulation. Further studies are needed to determine the specific mechanism of expansion and suppressive function of macrophages induced during helminth infection or ES proteins. Adoptive transfer of macrophages induced by T. spiralis is effective for preventing DSS-colitis and allergic airway inflammation and could be a promising therapeutic approach for immune diseases.

Methods

Animals

Six-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Orient Bio Inc (Seongnam, Korea). They were bred in-house at the Pusan National University specific pathogen-free animal facility and accommodated according to regulations. The animals were acclimatized at a temperature of 25 °C ± 2 °C and relative humidity of 50–60% under natural light and dark condition (12 h light-dark cycle) with standard diet for 1 week prior to experimentation.

Parasites and preparation of ES proteins of muscle larvae

The T. spiralis strain (isolate code ISS623) used in this study was maintained in our laboratory via serial passage in mice. The T. spiralis muscle larvae were collected as previously described90. After euthanizing mice via the inhalation of CO2 in a chamber, eviscerated mouse carcasses were cut into pieces and digested in 1% pepsin-hydrochloride digestion fluid for 1 h at 37 °C. The larvae were collected from the muscle digestion solution under a microscope. ES proteins were obtained as previously reported91.

Cell culture and stimulation

Bone marrow-derived macrophage cells (BMDMs) were prepared as previously described92. Briefly, bone marrow cells were flushed from tibiae and femurs of mice. BMDM were differentiated with macrophage colony-stimulating factor (20 ng/mL) containing in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin over 7 days at 37 °C. To evaluate the role of the ES proteins in macrophage activation, BMDM were left untreated or were treated with 1 μg/mL ES proteins, LPS (100 ng/mL), or IL-4 (20 ng/mL) for 24 h. The cells and culture supernatants were collected and stored at −80 °C for subsequent quantitative real-time PCR. Spleen, mesenteric lymph node (MLN) and lung draining lymph node (LLN) were harvested from mice euthanized by CO2 inhalation. Peritoneal macrophages were obtained from peritoneal lavage. Cells were isolated as previously reported35,36,90,93. Single cell suspensions were prepared by forcing tissue through a fine wire mesh using a syringe plunger, which was followed by repeated pipetting in RPMI-1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin. RBC depletion involved cell lysis in 3 mL ACK hypotonic lysis solution (Sigma-Aldrich).

Flow cytometry

To investigate macrophage transition during infection, live cells were isolated from the spleen and MLN of T. spiralis-infected mice at several times. The cell surfaces were stained with anti-F4/80-FITC(11-4801-82), anti-CD206-APC (17-2069-41) and anti-CD11c-PE (12-0114-82). anti-iNOS –PE cyanine7 (25-5920-82), and anti-Arginase 1-PerCP-eFluor 710 (46-3697-82)(eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) were stained using the Intracellular Fixation and Permeabilization Buffer Set in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations. During sample gating, cells were first gated for macrophages. The macrophage gate determined the F4/80-positive cells. CD206, CD 11c, iNOS and s Arginase 1 expression was then determined from this gated population.

Mouse model of DSS-colitis

A mouse model of DSS-colitis was induced as previously reported with a minor modification36,94. Mice in the colitis induction group received 3% (wt/vol) DSS (molecular weight, approximately 40,000; MP Biomedicals, LLC, Santa Ana, CA, USA) in drinking water for 4 days, and then received drinking water for 4 days. The mice were monitored every day for morbidity and their weights were recorded. The mice were examined for weight loss, rectal bleeding, and stool consistency. The disease activity index (DAI) was used to assess the grade of colitis as described previously94,95.

Mouse model of allergic airway inflammation

A mouse model of allergic airway inflammation was induced as previously reported35,96,97,98. Briefly, mice were sensitized by an intraperitoneal injection of 75 μg of OVA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 200 μL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10 mg/mL aluminum hydroxide (Sigma-Aldrich) on days 1, 2, 8, and 9. On days 15, 16, 22, and 23 after the initial sensitization, the mice were anesthetized by using isoflurane and challenged intranasally with 50 μg of OVA in 50 μL PBS (Fig. 1A). After the last OVA challenge, airway responsiveness was monitored for change in response to aerosolized methacholine (Sigma Chemical, USA) by using whole-body plethysmography for animals (Allmedicus, Korea). The enhanced pause (PenH) was evaluated at baseline (PBS) and after treatment with increasing doses of aerosolized methacholine (0–50 mg/mL) for obtaining measurements of bronchoconstriction. The mice were permitted to acclimate for 3 min, exposed to nebulized PBS for 10 min, and then subsequently treated in methacholine using an ultrasonic nebulizer (Omron, Japan) for 10 min. After each nebulization, the average PenH values were determined during each 3 min period. Analyses of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and airway responsiveness were conducted as previously reported35.

Cell transfer

First, peritoneal macrophages were isolated from T. spiralis-infected mice at 2 weeks post-infection. The cells were stained with CellTracker CM-DiI (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The mice were injected intravenously with 5 × 105 cells before the first DSS administration and OVA-alum sensitization [day 0]. Second, BMDM were isolated from C57BL/6 mice and treated with ES proteins (1 μg/mL) for 24 h. And then, the mice were injected intravenously with 5 × 105 cells before the first DSS administration and OVA-alum sensitization [day 0].

ELISA

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed to measure the culture supernatants of MLN, LLN, and BALF by using an ELISA kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (eBioscience).

Histopathology

Histological analyses were conducted as previously described99. Briefly, lungs were harvested from mice euthanized by CO2 inhalation. The left lobe of a lung and the large intestine (cecum, colon and rectum) were fixed in formaldehyde and paraffin-embedded. Thin sections of the embedded tissues were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E). After staining, the stained sections were evaluated under a microscope as previously described100.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

The large intestine and lung slides were rinsed in PBS and incubated with DAPI only for 2 min. Confocal images of stained tissue were obtained with an inverted microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) using the Zeiss LSM program (Jena, Germany).

Real-time PCR

Peritoneal macrophages and BMDMs were collected with 1 mL of QIAzol (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and RNA extraction was conducted in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocols for transcription of 2 μg of RNA. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR assays were performed by using AmpiGene q PCR Green Mix (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) in a LightCycler 96 Real-Time PCR System (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). GAPDH was used as a reference gene. The primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Western blot

Cell pellets were harvested, placed on ice, washed with PBS, and resuspended in 50 μL of PRO-PREP protein extraction solution (Intron Biotechnology, Sungnam, Korea). After incubation on ice for 30 min, the lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C to obtain the proteins. Protein concentrations were measured using Bradford reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). To analyze IRF3 phosphorylation, IRF4, IRF5, and ARG1 expression, 30 μg of total cellular protein was separated by 10% SDS gel electrophoresis at 100 V for 90 min. The separated proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Amersham, UK), and the membranes blocked overnight with 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Triton X-100. The membranes were washed five times and incubated with anti-IRF3 (rabbit monoclonal Ab, # 4302), anti-phospho-IRF3 (rabbit polyclonal Ab# 4961), anti-IRF4 (rabbit polyclonal Ab, # 4948), or anti-beta-actin (mouse monoclonal Ab#A5441) antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) diluted at 1:1000 in blocking buffer for overnight at 4 °C, and then underwent detection with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit antibody and anti-mouse antibody were used at a 1:1000 dilution for 1 hr at room temperature. The blot for horseradish peroxidase was developed by using ECL substrate (Amersham Bioscience).

Naïve T-cell differentiation and BMDM and naïve T-cell co-culture

Naïve T cells were isolated from the spleens and lymph nodes of C57BL/6 mice by using a CD4+CD62L+ T cells isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Briefly, non-CD4+ T cells were eliminated by incubating cells with a cocktail of biotin-conjugated antibodies and anti-biotin microbeads. Next, CD4+CD62L+ T cells were labeled with CD62L microbeads and isolated by positive selection. Isolated naive T cells were co-cultured with BMDM untreated or treated with ES proteins (1 μg/mL), LPS (100 ng/mL), or IL-4 (20 ng/mL) at a BMDM:T cell ratio of 1:5 at 37 °C for 72 h in 5% CO2. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with anti-CD3 antibody (1 μg/mL) for 72 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. The naive T-cell differentiation rate was evaluated by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) and applying Student’s t-test or ANOVA. For multivariate data analysis, group differences were assessed with one-way or two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. All experiments were conducted in triplicate and showed similar results. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD from each experiment.

Ethics statement

All animal studies presented were conducted in a specific pathogen-free facility at the Institute for Laboratory Animals of the Pusan National University. The experiments were registered and approved by the Pusan National University Animal Care and Use Committee (Approval No. PNU- 2016-1110) in accordance with “The Act for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” of Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, Korea.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All experimental procedures complied with the Guidelines and Policies for Ethical and Regulatory for Animal Experiments as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Pusan National University (Approval No. PNU-2016-1110).

Consent for publication

All co-authors gave consent for publication.

Data Availability

All relevant data are contained within the manuscript.

References

Bowdridge, S. & Gause, W. C. Regulation of alternative macrophage activation by chromatin remodeling. Nature immunology 11, 879–881 (2010).

O’Neill, L. A. & Pearce, E. J. Immunometabolism governs dendritic cell and macrophage function. The Journal of experimental medicine 213, 15–23 (2016).

Bhattacharya, S. & Aggarwal, A. M2 macrophages and their role in rheumatic diseases. Rheumatology international (2018).

Jablonski, K. A. et al. Novel Markers to Delineate Murine M1 and M2 Macrophages. PloS one 10, e0145342 (2015).

Martinez, F. O. & Gordon, S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000prime reports 6, 13 (2014).

Mills, C. D. Anatomy of a discovery: m1 and m2 macrophages. Frontiers in immunology 6, 212 (2015).

Wynn, T. A. & Vannella, K. M. Macrophages in Tissue Repair, Regeneration, and Fibrosis. Immunity 44, 450–462 (2016).

Ambarus, C. A. et al. Soluble immune complexes shift the TLR-induced cytokine production of distinct polarized human macrophage subsets towards IL-10. PLoS One 7, e35994 (2012).

Roszer, T. Understanding the Mysterious M2 Macrophage through Activation Markers and Effector Mechanisms. Mediators Inflamm 2015, 816460 (2015).

Wang, L. X., Zhang, S. X., Wu, H. J., Rong, X. L. & Guo, J. M2b macrophage polarization and its roles in diseases. J Leukoc Biol (2018).

Yue, Y. et al. M2b macrophages reduce early reperfusion injury after myocardial ischemia in mice: A predominant role of inhibiting apoptosis via A20. Int J Cardiol 245, 228–235 (2017).

Graff, J. W., Dickson, A. M., Clay, G., McCaffrey, A. P. & Wilson, M. E. Identifying functional microRNAs in macrophages with polarized phenotypes. J Biol Chem 287, 21816–21825 (2012).

Mantovani, A. et al. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol 25, 677–686 (2004).

Liu, G. & Yang, H. Modulation of macrophage activation and programming in immunity. Journal of cellular physiology 228, 502–512 (2013).

Wang, N., Liang, H. & Zen, K. Molecular mechanisms that influence the macrophage m1-m2 polarization balance. Frontiers in immunology 5, 614 (2014).

Davis, M. J. et al. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization dynamically adapts to changes in cytokine microenvironments in Cryptococcus neoformans infection. mBio 4, e00264–00213 (2013).

Lawrence, T. & Natoli, G. Transcriptional regulation of macrophage polarization: enabling diversity with identity. Nature reviews. Immunology 11, 750–761 (2011).

Gunthner, R. & Anders, H. J. Interferon-regulatory factors determine macrophage phenotype polarization. Mediators of inflammation 2013, 731023 (2013).

Chistiakov, D. A., Myasoedova, V. A., Revin, V. V., Orekhov, A. N. & Bobryshev, Y. V. The impact of interferon-regulatory factors to macrophage differentiation and polarization into M1 and M2. Immunobiology 223, 101–111 (2018).

Krausgruber, T. et al. IRF5 promotes inflammatory macrophage polarization and TH1-TH17 responses. Nature immunology 12, 231–238 (2011).

Weiss, M., Blazek, K., Byrne, A. J., Perocheau, D. P. & Udalova, I. A. IRF5 is a specific marker of inflammatory macrophages in vivo. Mediators of inflammation 2013, 245804 (2013).

Biswas, S. K. & Mantovani, A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nature immunology 11, 889–896 (2010).

Goriely, S. et al. Interferon regulatory factor 3 is involved in Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)- and TLR3-induced IL-12p35 gene activation. Blood 107, 1078–1084 (2006).

Chistiakov, D. A., Myasoedova, V. A., Revin, V. V., Orekhov, A. N. & Bobryshev, Y. V. The impact of interferon-regulatory factors to macrophage differentiation and polarization into M1 and M2. Immunobiology 223, 101–111 (2017).

Huang, S. C. C. et al. Metabolic Reprogramming Mediated by the mTORC2-IRF4 Signaling Axis Is Essential for Macrophage Alternative Activation. Immunity 45, 817–830 (2016).

Mangan, N. E., van Rooijen, N., McKenzie, A. N. & Fallon, P. G. Helminth-modified pulmonary immune response protects mice from allergen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness. J Immunol 176, 138–147 (2006).

Cancado, G. G. et al. Hookworm products ameliorate dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in BALB/c mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis 17, 2275–2286 (2011).

Kitagaki, K. et al. Intestinal helminths protect in a murine model of asthma. J Immunol 177, 1628–1635 (2006).

Hartmann, S. et al. Gastrointestinal nematode infection interferes with experimental allergic airway inflammation but not atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy 39, 1585–1596 (2009).

Grainger, J. R. et al. Helminth secretions induce de novo T cell Foxp3 expression and regulatory function through the TGF-beta pathway. J Exp Med 207, 2331–2341 (2010).

McSorley, H. J. et al. Suppression of type 2 immunity and allergic airway inflammation by secreted products of the helminth Heligmosomoides polygyrus. Eur J Immunol 42, 2667–2682 (2012).

Moreels, T. G. et al. Concurrent infection with Schistosoma mansoni attenuates inflammation induced changes in colonic morphology, cytokine levels, and smooth muscle contractility of trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid induced colitis in rats. Gut 53, 99–107 (2004).

Zhao, Y., Zhang, S., Jiang, L., Jiang, J. & Liu, H. Preventive effects of Schistosoma japonicum ova on trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid-induced colitis and bacterial translocation in mice. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 24, 1775–1780 (2009).

Ruyssers, N. E. et al. Worms and the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: are molecules the answer? Clin Dev Immunol 2008, 567314 (2008).

Kang, S. A. et al. Parasitic nematode-induced CD4+Foxp3+ T cells can ameliorate allergic airway inflammation. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8, e3410 (2014).

Cho, M. K. et al. Trichinella spiralis infection suppressed gut inflammation with CD4(+)CD25(+)Foxp3(+) T cell recruitment. Korean J Parasitol 50, 385–390 (2012).

Khan, A. R. & Fallon, P. G. Helminth therapies: translating the unknown unknowns to known knowns. International journal for parasitology 43, 293–299 (2013).

McSorley, H. J., Harcus, Y. M., Murray, J., Taylor, M. D. & Maizels, R. M. Expansion of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in mice infected with the filarial parasite Brugia malayi. Journal of immunology 181, 6456–6466 (2008).

O’Regan, N. L. et al. Brugia malayi Microfilariae Induce a Regulatory Monocyte/Macrophage Phenotype That Suppresses Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 8 (2014).

Sharma, A. et al. Infective Larvae of Brugia malayi Induce Polarization of Host Macrophages that Helps in Immune Evasion. Frontiers in immunology 9, 194 (2018).

Tang, C. L., Liu, Z. M., Gao, Y. R. & Xiong, F. Schistosoma Infection and Schistosoma-Derived Products Modulate the Immune Responses Associated with Protection against Type 2 Diabetes. Frontiers in immunology 8, 1990 (2017).

Beiting, D. P., Bliss, S. K., Schlafer, D. H., Roberts, V. L. & Appleton, J. A. Interleukin-10 limits local and body cavity inflammation during infection with muscle-stage Trichinella spiralis. Infection and immunity 72, 3129–3137 (2004).

Chang, N. C. et al. A macrophage protein, Ym1, transiently expressed during inflammation is a novel mammalian lectin. The Journal of biological chemistry 276, 17497–17506 (2001).

Chen, Z. B. et al. Recombinant Trichinella spiralis 53-kDa protein activates M2 macrophages and attenuates the LPS-induced damage of endotoxemia. Innate immunity 22, 419–432 (2016).

Shechter, R. et al. Infiltrating blood-derived macrophages are vital cells playing an anti-inflammatory role in recovery from spinal cord injury in mice. PLoS Med 6, e1000113 (2009).

Munn, D. H., Pressey, J., Beall, A. C., Hudes, R. & Alderson, M. R. Selective activation-induced apoptosis of peripheral T cells imposed by macrophages. A potential mechanism of antigen-specific peripheral lymphocyte deletion. J Immunol 156, 523–532 (1996).

Miyake, Y. et al. Critical role of macrophages in the marginal zone in the suppression of immune responses to apoptotic cell-associated antigens. J Clin Invest 117, 2268–2278 (2007).

Weber, M. S. et al. Type II monocytes modulate T cell-mediated central nervous system autoimmune disease. Nat Med 13, 935–943 (2007).

Savage, N. D. et al. Human anti-inflammatory macrophages induce Foxp3+GITR+CD25+ regulatory T cells, which suppress via membrane-bound TGFbeta-1. J Immunol 181, 2220–2226 (2008).

El Kasmi, K.C. & Stenmark, K.R. Contribution of metabolic reprogramming to macrophage plasticity and function. Seminars in immunology (2015).

Sica, A. & Mantovani, A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. The Journal of clinical investigation 122, 787–795 (2012).

Broadhurst, M. J. et al. Upregulation of retinal dehydrogenase 2 in alternatively activated macrophages during retinoid-dependent type-2 immunity to helminth infection in mice. PLoS pathogens 8, e1002883 (2012).

Motran, C. C. et al. Helminth Infections: Recognition and Modulation of the Immune Response by Innate Immune Cells. Frontiers in immunology 9, 664 (2018).

Allen, J. E. & Maizels, R. M. Diversity and dialogue in immunity to helminths. Nature reviews. Immunology 11, 375–388 (2011).

Gordon, S. & Martinez, F. O. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity 32, 593–604 (2010).

Melgert, B. N. et al. Macrophages Regulators of Sex Differences in Asthma? Am J Resp Cell Mol 42, 595–603 (2010).

Melgert, B. N. et al. More alternative activation of macrophages in lungs of asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immun 127, 831–833 (2011).

Draijer, C., Robbe, P., Boorsma, C. E., Hylkema, M. N. & Melgert, B. N. Characterization of Macrophage Phenotypes in Three Murine Models of House-Dust-Mite-Induced Asthma. Mediat Inflamm (2013).

Martinez, F. O. et al. Genetic programs expressed in resting and IL-4 alternatively activated mouse and human macrophages: similarities and differences. Blood 121, e57–69 (2013).

Arranz, A. et al. Akt1 and Akt2 protein kinases differentially contribute to macrophage polarization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 9517–9522 (2012).

Heinsbroek, S. E. M. & Gordon, S. The role of macrophages in inflammatory bowel diseases. Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine 11 (2009).

Weisser, S. B. et al. SHIP-deficient, alternatively activated macrophages protect mice during DSS-induced colitis. J Leukocyte Biol 90, 483–492 (2011).

Hunter, M. M. et al. In Vitro-Derived Alternatively Activated Macrophages Reduce Colonic Inflammation in Mice. Gastroenterology 138, 1395–1405 (2010).

Lin, Y. L. et al. Chemerin aggravates DSS-induced colitis by suppressing M2 macrophage polarization. Cellular & Molecular Immunology 11, 355–366 (2014).

Wiria, A. E., Djuardi, Y., Supali, T., Sartono, E. & Yazdanbakhsh, M. Helminth infection in populations undergoing epidemiological transition: a friend or foe? Seminars in immunopathology 34, 889–901 (2012).

Hewitson, J. P., Grainger, J. R. & Maizels, R. M. Helminth immunoregulation: the role of parasite secreted proteins in modulating host immunity. Molecular and biochemical parasitology 167, 1–11 (2009).

Pelly, V. S. et al. Interleukin 4 promotes the development of ex-Foxp3 Th2 cells during immunity to intestinal helminths. The Journal of experimental medicine 214, 1809–1826 (2017).

Smyth, D. J. et al. TGF-beta mimic proteins form an extended gene family in the murine parasite Heligmosomoides polygyrus. International journal for parasitology 48, 379–385 (2018).

Bian, K. et al. Down-regulation of inducible nitric-oxide synthase (NOS-2) during parasite-induced gut inflammation: a path to identify a selective NOS-2 inhibitor. Molecular pharmacology 59, 939–947 (2001).

Passos, L. S. A. et al. Regulatory monocytes in helminth infections: insights from the modulation during human hookworm infection. BMC infectious diseases 17 (2017).

Rolot, M. & Dewals, B. G. Macrophage Activation and Functions during Helminth Infection: Recent Advances from the Laboratory Mouse. Journal of immunology research (2018).

Steinfelder, S., O’Regan, N. L. & Hartmann, S. Diplomatic Assistance: Can Helminth-Modulated Macrophages Act as Treatment for Inflammatory Disease? PLoS pathogens 12 (2016).

Bai, X. et al. Regulation of cytokine expression in murine macrophages stimulated by excretory/secretory products from Trichinella spiralis in vitro. Molecular and cellular biochemistry 360, 79–88 (2012).

Yang, X. D. et al. Excretory/Secretory Products from Trichinella spiralis Adult Worms Ameliorate DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice. PloS one 9 (2014).

Ilic, N. et al. Trichinella spiralis excretory-secretory Products induce Tolerogenic Properties in human Dendritic cells via Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Frontiers in immunology 9 (2018).

Maizels, R. M. & McSorley, H. J. Regulation of the host immune system by helminth parasites. J Allergy Clin Immun 138, 666–675 (2016).

Savitsky, D., Tamura, T., Yanai, H. & Taniguchi, T. Regulation of immunity and oncogenesis by the IRF transcription factor family. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy: CII 59, 489–510 (2010).

Satoh, T. et al. The Jmjd3-Irf4 axis regulates M2 macrophage polarization and host responses against helminth infection. Nature immunology 11, 936–944 (2010).

Wiesner, D. L. et al. Chitin Recognition via Chitotriosidase Promotes Pathologic Type-2 Helper T Cell Responses to Cryptococcal Infection. PLoS pathogens 11 (2015).

Donnelly, S., O’Neill, S. M., Sekiya, M., Mulcahy, G. & Dalton, J. P. Thioredoxin peroxidase secreted by Fasciola hepatica induces the alternative activation of macrophages. Infection and immunity 73, 166–173 (2005).

Valero, M. A. et al. Fasciola hepatica reinfection potentiates a mixed Th1/Th2/Th17/Treg response and correlates with the clinical phenotypes of anemia. PloS one 12 (2017).

Leung, G., Wang, A., Fernando, M., Phan, V. C. & McKay, D. M. Bone marrow-derived alternatively activated macrophages reduce colitis without promoting fibrosis: participation of IL-10. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology 304, G781–792 (2013).

Meers, G. K., Bohnenberger, H., Reichardt, H. M., Luhder, F. & Reichardt, S. D. Impaired resolution of DSS-induced colitis in mice lacking the glucocorticoid receptor in myeloid cells. PloS one 13, e0190846 (2018).

Mills, C. D., Kincaid, K., Alt, J. M., Heilman, M. J. & Hill, A. M. M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. Journal of immunology 164, 6166–6173 (2000).

Yang, M. et al. Inhibition of arginase I activity by RNA interference attenuates IL-13-induced airways hyperresponsiveness. Journal of immunology 177, 5595–5603 (2006).

Monin, L. et al. Helminth-induced arginase-1 exacerbates lung inflammation and disease severity in tuberculosis. The Journal of clinical investigation 125, 4699–4713 (2015).

Rodriguez, P. C. et al. Regulation of T cell receptor CD3zeta chain expression by L-arginine. The Journal of biological chemistry 277, 21123–21129 (2002).

Bronte, V. & Zanovello, P. Regulation of immune responses by L-arginine metabolism. Nature reviews. Immunology 5, 641–654 (2005).

Taylor, M. D., Harris, A., Nair, M. G., Maizels, R. M. & Allen, J. E. F4/80+ alternatively activated macrophages control CD4+ T cell hyporesponsiveness at sites peripheral to filarial infection. J Immunol 176, 6918–6927 (2006).

Kang, S. A. et al. Alteration of helper T-cell related cytokine production in splenocytes during Trichinella spiralis infection. Veterinary parasitology 186, 319–327 (2012).

Park, M. K. et al. Protease-activated receptor 2 is involved in Th2 responses against Trichinella spiralis infection. The Korean journal of parasitology 49, 235–243 (2011).

Lutz, M. B. et al. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. Journal of immunological methods 223, 77–92 (1999).

Zhang, X., Goncalves, R. & Mosser, D. M. The isolation and characterization of murine macrophages. Current protocols in immunology Chapter 14, Unit 14 11 (2008).

Kim, J. Y. et al. Inhibition of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced intestinal inflammation via enhanced IL-10 and TGF-beta production by galectin-9 homologues isolated from intestinal parasites. Molecular and biochemical parasitology 174, 53–61 (2010).

Jang, S. W. et al. Parasitic Helminth Cystatin Inhibits DSS-Induced Intestinal Inflammation Via IL-10(+)F4/80(+) Macrophage Recruitment. Korean Journal of Parasitology 49, 245–254 (2011).

Park, H. K., Cho, M. K., Choi, S. H., Kim, Y. S. & Yu, H. S. Trichinella spiralis: infection reduces airway allergic inflammation in mice. Experimental parasitology 127, 539–544 (2011).

Yu, H. S. et al. Culture supernatant of adipose stem cells can ameliorate allergic airway inflammation via recruitment of CD4+CD25+ Foxp3 T cells. Stem cell research & therapy 8, 8 (2017).

Park, M. K. et al. Acanthamoeba protease activity promotes allergic airway inflammation via protease-activated receptor 2. PloS one 9, e92726 (2014).

Trujillo-Vargas, C. M. et al. Vaccinations with T-helper type 1 directing adjuvants have different suppressive effects on the development of allergen-induced T-helper type 2 responses. Clin Exp Allergy 35, 1003–1013 (2005).

Taube, C. et al. Mast cells, Fc epsilon RI, and IL-13 are required for development of airway hyperresponsiveness after aerosolized allergen exposure in the absence of adjuvant. J Immunol 172, 6398–6406 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2017R1D1A3B05035680).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A.K. participated in collecting data, statistical analysis of the results, writing the “Abstract”, “Materials and Methods” and “Results” sections and collecting the results that contributed to the “Discussion”. H.S.Y. designed the study and revised the manuscript. S.K.P. and J.H.C. participated in the colitis experiments. D.I.L. participated in the asthma experiments. M.K.P. carried out the in vitro experiments. K.S.C. designed the study and the methods, isolated the stem cells from mice and analyzed the stem cell characteristics. S.M.S. contributed to producing the pathology scores, pathology results, and imaging. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, S.A., Park, MK., Park, S.K. et al. Adoptive transfer of Trichinella spiralis-activated macrophages can ameliorate both Th1- and Th2-activated inflammation in murine models. Sci Rep 9, 6547 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43057-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43057-1

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Colonization with ubiquitous protist Blastocystis ST1 ameliorates DSS-induced colitis and promotes beneficial microbiota and immune outcomes

npj Biofilms and Microbiomes (2023)

-

Regulation of human THP-1 macrophage polarization by Trichinella spiralis

Parasitology Research (2021)

-

Trichinella spiralis co-infection exacerbates Plasmodium berghei malaria-induced hepatopathy

Parasites & Vectors (2020)