Abstract

Phosphodiesterases (PDEs) are enzymes involved in the homeostasis of both cAMP and cGMP. They are members of a family of proteins that includes 11 subfamilies with different substrate specificities. Their main function is to catalyze the hydrolysis of cAMP, cGMP, or both. cAMP and cGMP are two key second messengers that modulate a wide array of intracellular processes and neurobehavioral functions, including memory and cognition. Even if these enzymes are present in all tissues, we focused on those PDEs that are expressed in the brain. We took into consideration genetic variants in patients affected by neurodevelopmental disorders, phenotypes of animal models, and pharmacological effects of PDE inhibitors, a class of drugs in rapid evolution and increasing application to brain disorders. Collectively, these data indicate the potential of PDE modulators to treat neurodevelopmental diseases characterized by learning and memory impairment, alteration of behaviors associated with depression, and deficits in social interaction. Indeed, clinical trials are in progress to treat patients with Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, depression, and autism spectrum disorders. Among the most recent results, the application of some PDE inhibitors (PDE2A, PDE3, PDE4/4D, and PDE10A) to treat neurodevelopmental diseases, including autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability, is a significant advance, since no specific therapies are available for these disorders that have a large prevalence. In addition, to highlight the role of several PDEs in normal and pathological neurodevelopment, we focused here on the deregulation of cAMP and/or cGMP in Down Syndrome, Fragile X Syndrome, Rett Syndrome, and intellectual disability associated with the CC2D1A gene.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The family of phosphodiesterases

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) are second messengers that regulate a variety of signaling pathways via direct interaction with cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) and cAMP-dependent protein kinase G (PKG), respectively [1]. Adenylate and guanylate cyclases (AC and GC) catalyze the synthesis of cAMP and cGMP starting from ATP and GTP, respectively. In the brain, activation of AC is mediated by heterotrimeric G proteins upon activation of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) by extracellular stimuli (Fig. 1), while soluble AC is directly activated by Ca2+ [2] (Fig. 1). In the brain, soluble GC is mainly activated by nitric oxide (NO) and transmembrane GC is activated by C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) [3] (Fig. 1). cAMP and cGMP are hydrolized by phosphodiesterases (PDEs). The enzymatic activity of PDEs was used as one of the initial processes providing evidence for the physiological importance of cAMP. Today, we know that PDEs catalyze the hydrolysis of the 3′ phosphate bond of cAMP and cGMP to generate 5′ AMP and 5′ GMP, respectively [1]. Mammalian PDEs are classified in 11 subfamilies of proteins encoded by 21 different genes, each one displaying multiple splice variants. These spliced variants often have different subcellular localization (Fig. 2) [1, 4]. PDEs are divided into three groups based on their specificity to cyclic nucleotides: specific to cAMP (PDE4, PDE7, and PDE8), specific to cGMP (PDE5, PDE6, and PDE9), and hydrolyzing both cAMP and cGMP (PDE1, PDE2, PDE3, PDE10, and PDE11). The PDEs in the last group have a higher affinity for one of the two cyclic nucleotides [1, 4]. This specificity is associated with a “glutamine switch”, a highly conserved glutamine residue that regulates the binding of the cyclic nucleotide purine ring in the binding domain [5]. The structural features of these enzymes, their regulatory domains, and catalytic regions are common among isoforms and are highly conserved across species. In each subfamily, the main variable regions between each member are the N- and C-terminal domain-containing elements for subcellular localization that is a critical element to define the specific function of each PDE [4, 6]. In Fig. 2, the 11 subfamilies are shown and for each one the functional domains are presented. Moreover, the activity of some PDEs depends on cGMP (PDE2, PDE3, PDE5, and PDE6), while cAMP activates PDE10A [1] (Fig. 1). PDEs are expressed in the cells of all tissues. The precise spatiotemporal expression of PDEs is crucial for the accurate regulation of cAMP and cGMP levels. Indeed, all PDEs appear to be expressed in the brain according to http://mousebrain.org/celltypes/ and each PDE displays a specific expression pattern, as illustrated in Supplementary Table I [7]. A study by Lakics et al. compared the expression levels of PDEs in different human brain regions [8]. In Supplementary Table II, we summarize the results of this study indicating the 2–3 most highly expressed PDEs in each of the analyzed brain regions. The expression of PDEs during brain development is poorly studied. In Supplementary Table III, we summarized the studies on this subject reported on Mouse Brain Atlas https://mouse.brain-map.org/static/atlas.

Schematic of the regulation of cAMP synthesis by Adenylate Cyclases (AC) or s(soluble)AC and of cGMP synthesis by guanylate cyclases (GC) or s(soluble)GC. Specific degradation of cAMP and cGMP is catalyzed by various PDEs whose specificity is shown. Targets of cAMP and cGMP are shown, as well as well-known neuronal pathways involved in neurodevelopment. Red arrows indicate inhibition while green arrows indicate activation. PKA cAMP-dependent Protein Kinase, Ca2+CaM Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, EPAC Exchange Protein directly Activated by cAMP, Rap Ras-related protein, ERK Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinase, Raf rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma, DARP32 dopamine- and cAMP-regulated neuronal phosphoprotein, PP1 protein phosphatase-1, MEK MitogEn-activated protein kinase Kinase, PKG cGMP-dependent protein kinase, PrKG protein kinase, cGMP-dependent, GSK3 glycogen synthase kinase 3, iNOS inducible nitric oxide synthase; NO nitric oxide, CREB cAMP response element-binding protein, CNP C-type natriuretic peptide.

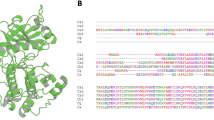

Left panel. The structure of each PDE subfamily is indicated by representing the various domains. Catalytic domain providing the substrate specificity: CAT. Regulatory domains: GAF: the name is related to the proteins it is found in: cGMP-specific phosphodiesterases, adenylyl cyclases and the bacterial transcription factor FhlA. Ca2+CaM Ca2+/calmodulin binding site; PAS Per-ARNT-Sim domain, that is a structural motif. TD transmembrane domain. REC cheY-homologous receiver domain. UCR upstream conserved region. ISD isoform specific domain. Regions that are submitted to alternative splicing have been indicated as VSD variant-specific domain. This domain is called PAT7 in PDE9A variants [148] Pγ is part of the PDE6 holoenzyme in rod. Isoforms originated by different genes exist and are indicated for the following subfamily: PDE1 (A, B, and C), PDE3 (A and B), PDE4 (A, B, C and D), PDE6 (A, B and C), PDE7 (A and B) and PDE8 (A and B). PDE2, PDE5, PDE9, PDE10 and PDE11 subfamilies are represented by only one member, namely PDE2A, PDE5A, PD9A, PDE10A and PDE11A. Splicing variants (in blue) of the same protein are indicated when they determine a specific subcellular localization. Middle panel. Localization of each isoform and variant is indicated [4, 6, 148]. Cy Cytosol, Me membrane; Mi mitochondria; Nu Nucleus. Right panel. Brain disorders involving the various PDEs are indicated according to all the genetic and pharmacological information considered in the text. Neurodevelopmental disorders are highlighted in red. AD Alzheimer disease; ASD autism spectrum disorder; BP bipolar disorder; DS down syndrome; HD Huntington disease; ID intellectual disability; FXS fragile X syndrome; MDD major depression disorder, RTT Rett syndrome, SCZ schizophrenia.

Role of PDEs in the brain

In the brain, both cAMP and cGMP are essential during neurodevelopment as well as in maintaining synaptic plasticity, and ultimately in learning and memory [9,10,11]. Indeed, it has been reported that the levels of both cAMP and cGMP have critical roles in axon elongation and guidance [12, 13] and in regulating the morphology and growth of dendritic spines, where they have opposite effect [12]. cAMP abundance coupled to PKA signaling is critical to modulate assembly/disassembly/priming/recycling of neurotransmitter vesicles and, consequently, for synaptic transmission and plasticity events [14]. cGMP signaling can be transmitted through cyclic nucleotide-gated or hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of soluble GC or PKG slowed down the rate of recycling as well as endocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Indeed, the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway is known to modulate transmitter release and long-term changes of synaptic activity in various brain regions [15]. Overall, the balance between cAMP and cGMP levels is considered to be essential for shaping neuronal circuits [16]. Both cAMP- and cGMP-dependent signaling have been involved in neuronal migration [17]. In particular, a recent study suggested that primary cilium and centrosome integrate the cAMP signaling to favor neuronal migration [18]. Signal transduction starts when cAMP and cGMP induce the activation of PKA and PKG, respectively. Hence, PKA and PKG phosphorylate key proteins of a large array of downstream pathways. As an example, Fig. 1 illustrates the role of PKA and PKG in pathways involved in learning and memory (e.g., cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) [19]) and in a large number of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders (e.g., GSK3) [20]. Furthermore, cAMP activates the exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (EPAC), which regulates kinases (e.g., ERK and Raf) and Rap GTP-binding protein, a small-GTPase similar to Ras. These factors have key roles in modulation of molecular signaling involved in various aspects of neuronal differentiation, like the establishment of neuronal polarity or axonal growth and cone movement [21,22,23,24] (Fig. 1).

Genetic evidence of the implication of PDEs in neurodevelopmental disorders

Recent large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) conducted by the Science Genetic Association Consortium [25] linked genetic variation in some PDE genes with multiple measures of human cognitive function. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) found in PDE1C, PDE2A, PDE4B, and PDE4D reached genome-wide significance with educational attainment and cognitive performance [26]. Of note, in this study, the highest statistical significance was reached by SNP rs72962169 in the PDE2A gene for GWAS/Educational attainment as measured by the highest level of education achieved (Eduyears), conjoint analysis/Eduyears, and multi-trait analysis/Eduyears [25]. Starting from this information, we considered here the genetic evidence in patients and in transgenic animals (See also Supplementary Table IV) supporting the implication of PDEs in neurodevelopmental brain disorders.

Three PDE1 genes (PDE1A, PDE1B, and PDE1C) have thus far been identified. Enzyme activity is increased by Ca2+/calmodulin binding to the regulatory site located in the N-terminal region of the enzyme [27]. An intronic SNP in the PDE1C gene was found to be associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD; p value < 1.0E−04) in a GWAS meta-analysis of 7387 ASD cases and 8567 controls [28]. Inherited missense variants in PDE1B gene have also been identified in probands with ASD [29] and with schizophrenia (SCZ) [30]. The knockdown of Pde1b in the hippocampus enhances spatial and contextual memory [31]. Conversely, Pde1b-knockout (KO) mice display locomotor hyperactivity, spatial learning deficits [32], and antidepressant-like phenotypes [33]. These findings indicate the need to tightly modulate Pde1b expression levels by pharmacological approaches to observe an impact on socio-cognitive behavior.

PDE2A is a dual-specific PDE that breaks down both cAMP and cGMP and is activated by cGMP. A homozygous splicing mutation in PDE2A was found in two patients with atypical Rett syndrome (RTT), displaying neurodevelopmental delay [34], while a homozygous loss-of-function mutation in PDE2A was associated with early-onset hereditary chorea-predominant movement disorder and intellectual disability (ID) [35]. Patients with bipolar disorder showed reduced PDE2A mRNA levels in the hippocampus, caudal entorhinal cortex, and striatum, while patients with SCZ, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder (MDD) showed reduced PDE2A mRNA levels in the amygdala. Furthermore, patients with schizophrenia have reduced PDE2A mRNA levels in the frontal cortical region [36]. Pde2a-KO mice have been generated but they are lethal during embryogenesis due to cardiac failure [37]. To our knowledge, no studies have been performed on heterozygous animals so far.

The PDE4 family comprises four genes, PDE4A–D, each expressed as multiple variants. The selective modulation of individual PDE4 subtypes revealed that individual subtypes exert unique and non-redundant functions in the brain [38]. The role of PDE4 in learning and memory has been studied extensively in the Drosophila fruit fly, where only one homolog of the family known as dunce (dnc) is present, and in mice. Mutational studies in flies have identified PDE4 as a key modulator of a signaling pathway critical for associative learning, courtship behavior, and neurodevelopment. Deletion of the dnc gene in Drosophila disrupts learning and memory by preventing the hydrolysis of cAMP, thereby altering the normal spatial and temporal patterning of cAMP signaling [39, 40].

PDE4B interacts directly with DISC1, which is a well-known genetic risk factor for mental illness. Mutations in the DISC1 and PDE4B genes reduce the association between both proteins, reducing PDE4B activity, which has been shown to be correlated with SCZ [41]. In particular, it was reported that an SNP in PDE4B conferred a protective effect against SCZ in women [42]. The implication of the PDE4B gene in behavior and mood is also supported by the association of PDE4B gene polymorphisms with protection from panic disorder in Russians subjects [43]. Pde4b-KO mice show a significant reduction in prepulse inhibition and an exaggerated locomotor response to amphetamine correlated with decreased striatal dopamine and serotonin activity [44]. Pde4b-KO mice display enhanced early long-term potentiation following multiple induction protocols, and they exhibit significant behavioral deficits in associative learning using a conditioned fear paradigm [45]. In addition, they display decreased head-dips and time spent in head-dipping in the hole-board test, reduced transitions and time on the light side in the light–dark transition test, and decreased initial exploration and rears in the open-field test were observed [46]. Overall, these studies suggest that PDE4B is involved in signaling pathways that contribute to anxiogenic-like effects on behavior [46]. PDE4D mutations have been reported as causative for acrodysostosis type 2 with or without hormone resistance (ACRDYS2), a disorder characterized by severe ID [47, 48], leading to the conclusion that altered PDE4D levels may affect brain functioning. Pde4d-KO mice exhibit decreased immobility in tail suspension and forced swim tests [49], suggesting that PDE4D may play a role in the pathophysiology and pharmacotherapy of depression.

PDE10A is a dual-specific PDE that breaks down both cAMP and cGMP. Pde10-KO mice display a modest impairment of latent inhibition, a decrease in exploratory locomotor activity, and a delay in the acquisition of conditioned avoidance responses. Furthermore, a decrease in spontaneous firing in striatal medium spiny neurons and a significant change in striatal dopamine turnover, which is accompanied by an enhanced locomotor response to amphetamines, was observed in these mice [50]. All these data support the strong implication of PDE10A in striatal function, and thus its possible involvement in the pathophysiology of disorders such as Huntington (HD) and Parkinson disease (PD) and SCZ [51,52,53] (see below).

PDE11A is also a dual-specific PDE that breaks down both cAMP and cGMP. PDE11A4, one of the four PDE11A splice variants, is involved in the hippocampal formation in humans and rodents, and is highly enriched in the rodent ventral hippocampal formation compared to the dorsal hippocampal formation [54]. Pde11A-KO mice show enlarged lateral ventricles and increased activity in CA1, altered formation of social memories and abnormal stabilization of mood [54, 55]. This latter conclusion is also supported by other authors associating PDE11A with both MDD and response to antidepressant drugs [56]. Indeed, 16 SNPs in PDE11A were studied in patients affected by MDD and sharing 18 common haplotypes. Six haplotypes showed significantly different frequencies between the MDD group and the control group. Furthermore, in patients treated with two different antidepressant drugs—increasing the cGMP/cAMP ratio [57, 58]—the frequency of one haplotype was significantly lower in the remitter group than in the nonremitter group [56].

Pharmacological modulation of PDEs

Similar to the generation of animal models, the identification of specific and powerful inhibitors of PDEs allowed studying the functional role of these enzymes, paving the way for their use in the clinic.

A well-known inhibitor of PDE1B is DSR-141562, which inhibits locomotor hyperactivity and reverses social interaction and novel object recognition in normal mice and rats. This molecule was also shown to improve cognition in the marmoset, a non-human primate [59] by acting through CREB and DARPP32 [32, 59] (Fig. 1). DSR-141562 has been proposed as a therapeutic candidate for positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia [59].

Many specific PDE2A inhibitors have been generated and characterized. Hcyb1 produces neuroprotective and antidepressant‐like effects in mice [60]. TAK-915 shows efficacy in ameliorating cognitive and social impairment in induced rat models of SCZ [61] and it improves cognitive impairment associated with aging in mice [62]. To date, one phase I clinical trial has been reported for this compound (Supplementary Table V). A clinical trial has been carried out using a specific PDE2A inhibitor by Pfizer to treat migraine, but the results have not been communicated to the scientific community (Supplementary Table V). This study suggests a possible role of PDE2A in pain control. This hypothesis is supported by a study reporting that Bay 60–7550, another well-known inhibitor of PDE2A, alleviates radicular inflammation and mechanical allodynia in a rat model of non-compressive lumbar disc herniation [63]. Bay 60–7550 is likely the most studied PDE2A inhibitor, probably due to its commercial availability. It has been reported to have anxiolytic properties and to ameliorate learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity in normal animals [64,65,66] and in neurodegeneration models [67, 68]. This drug could also be used for treatment of alcoholism since it was reported to decrease ethanol intake and preference in mice [69]. Despite all these results, no clinical trials testing Bay 60–7550 have been reported, suggesting possible toxicity of this compound. Controversial results concerning the poor ability to cross the blood-brain barrier after oral administration to adult rats [64, 70] and the efficacy of this drug in treating brain disorders when used by intraperitoneal injection in adult and infant mice and rats, might suggest that the bioavailability of Bay 60–7550 in the brain is dependent on the route of administration and/or by the age of the treated subject [65, 71, 72]. PDE2A has been also involved in the pathophysiology of FXS (see below).

Cilostazol is the most studied PDE3-specific inhibitor already used in clinics for the treatment of symptoms of intermittent claudication due to its vasodilator and antiplatelet actions [73]. A clinical trial in patients with mild cognitive impairment is in progress using this compound (Supplementary Table V). This new potential use of cilostazol is based on retrospective study showing that patients using this drug daily as an antiplatelet drug have a decreased risk of developing dementia [74] and reduces the decline in cognitive function in patients with stable AD [75]. In the hippocampus, Cilostazol increases the levels of c-fos and of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) [76] and activates CREB in PC12 cells [77].

Several clinical trials have been carried out using roflumilast, a highly specific PDE4 inhibitor. Double-blind studies have shown that acute treatment with roflumilast improves verbal memory performance in elderly and healthy participants [78] and in patients with SCZ [79]. FCPR16 also shows antidepressant-like effects in mice exposed to chronic unpredictable mild stress [80]. Rolipram is another well-known PDE4 inhibitor, whose utilization results into the increased phosphorylation of CREB [81]. Consistently, a single injection of rolipram improves spatial memory deficits in aged mice [82] and memory consolidation of conditioned fear [81]. Furthermore, in the model of Amyloidβ-induced memory impairment, mimicking AD, both treatments with rolipram or BPN14770 improve memory performances [83,84,85]. Rolipram abolishes long-term memory defects in a mouse model of Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, caused by the presence of a truncated form of CREB [86] and has antipsychotic properties [87]. This drug was used to improve the phenotype of both fly and mouse models of FXS [88].

PDE5 inhibitors are essential for the vascular effects and treatment of erectile dysfunction. However, PDE5A inhibitors have been implicated in memory function in various studies. In rats, sildenafil, an inhibitor of PDE5, promotes neurogenesis, reduces neurological deficits, and promotes functional recovery after stroke and focal cerebral ischemia [89]. In addition, this drug improves cognition and spatial learning [90, 91]. Sildenafil has been shown to produce long-lasting amelioration of synaptic function, CREB phosphorylation and to increase Brain-Derived Neutrophic Factor (BDNF) levels [92]. In humans, sildenafil affects selective auditory attention and verbal recognition memory [93]. In particular in AD patients, a single dose of this drug increased cerebral blood flow and the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen [92].

WYQ-C36D, a high-affinity PDE9A inhibitor, produces antidepressant-like, anxiolytic-like, and memory-enhancing effects in stressed mice [94]. Inhibition of PDE9A in rats with PF-4447943 and PF-4449613 demonstrated the implication of this PDE in tasks depending on hippocampal cholinergic function and sensory gating. These results suggested the utilization of PDE9A inhibitors to treat AD, SCZ, or HD [95]. However, two double-blind randomized controlled phase II studies using two different inhibitors of PDE9A, namely BI 409306 or PF-04447943, failed to prove efficacy in improving cognition in patients with AD [96, 97]. Another clinical trial testing the effect of BI 409306 on SCZ patients is currently ongoing (Supplementary Table V). Recently, the treatment of a HD rat model with PF-4447943 suggested that this drug facilitates striatal cGMP signaling and glutamatergic cortico-striatal transmission. This could help to alleviate motor and cognitive symptoms associated with HD by restoring striatal function [98].

Data obtained by studying a mouse model supported the pivotal role of PDE10A in striatal signaling and striatum-mediated salience attribution, a process that is severely disrupted in patients affected by schizophrenia [99]. Indeed, TAK-063 (Balipodect) and T-251 dose-dependently suppress hyperactivity and improve cognitive deficits, respectively, in MK-801 mice, a model for acute psychosis [99, 100]. A phase II randomized and placebo-controlled clinical trial showed a potential beneficial effect of TAK-063 in subjects with acute exacerbation of SCZ [101]. Two clinical trials are currently testing another PDE10A inhibitor, Lu AF11167, for the treatment of negative symptoms in patients with SCZ (Supplementary Table V). These latter results are consistent with the observation that Pde10a mRNA is a target of miR-137, whose absence is associated with SCZ. Partial loss of miR-137 in heterozygous conditional KO mice results in increased PDE10A levels and in deregulated synaptic plasticity, repetitive behavior, and impaired learning and social behavior. Both treatment with papaverine, a PDE10A inhibitor, and knockdown of Pde10a ameliorate the deficits observed in the miR-137 mouse model [102]. PDE10 inhibition increases the expression of BDNF and the phosphorylation of both CREB and the alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate (AMPA) receptor GLUA1 in a mouse model of HD [103]. Of note, the implication of this receptor in neurodevelopmental disorders is well known [104]. Indeed, recently, papaverin has been reported to attenuate neurobehavioral abnormalities in a rat model of ASD [105] and to ameliorate hyperactivity, inattention and anxiety in a model of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [106].

Altered activity of PDEs in neurodevelopmental disorders—preclinical conclusion and translational elements

Down syndrome (DS) is the most frequent form of ID (1:600 newborns) and is caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21. A specific region on this chromosome, namely the DS critical region, is necessary and sufficient to produce the main phenotype of DS: cognitive congenital malformations (particularly cardiovascular) and dysmorphic features. Immune disturbances in DS account for autoimmune alopecia, autoimmune thyroiditis and leukemia, respiratory tract infections, and pulmonary hypertension [107]. Several genes in triple dosage have been reported to contribute to ID in patients with DS. The most studied is the dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A (DYRK1A) gene encoding a kinase involved in the formation and maturation of dendritic spines from dendrites [108]. Mutations in DYRK1A have been found in patients affected by ASD [109]. DYRK1A has CREB among its targets [110], whose activity is regulated by both cAMP and cGMP (Fig. 1), thus suggesting a clear interference of deregulated expression of DYRK1A in cAMP and/or cGMP pathway in DS. Another factor with elevated expression levels in DS is the amyloid precursor protein. This deregulated expression is likely the cause of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques that are present in young patients with DS and represent one of the neuropathology hallmarks shared between DS and AD [111]. As reported in Supplementary Table V, several clinical trials to treat AD with PDE inhibitors are currently ongoing. Hence, this information, together with reduced levels of cAMP reported in one of the most-widely used models of DS, the Ts65Dn mouse [112], pushed some authors to study the implication of PDE activity in the pathophysiology of DS. In a recent study, the administration of cilostazol (PDE3 inhibitor) to Ts65Dn mice from fetal to adult age ameliorated cognition and sensorimotor function in females. The same treatment in males improved their hyperactive locomotion and spatial memory [113]. Overall, these results seem to be consistent with the previous observation that cilostazol promotes the clearance of Aβ plaques and rescues cognitive deficits in a mouse model [113] of AD and reduces the cognitive decline in patients affected by AD [75].

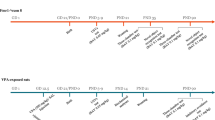

FXS is caused by the silencing of the fragile X mental retardation gene (FMR1). FXS is the most common form of inherited ID (1:4000 males and 1:7000 females). Patients might also display hyperactivity, attention deficit, ASD, language problems, and seizures [114]. Deregulation of cAMP was one of the first molecular hallmarks defined in FXS patients [115]. FMR1 encodes the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), an RNA-binding protein that is highly expressed in all brain regions in both neurons and glial cells and mainly involved in translational regulation, being both a repressor and an enhancer of translation [116]. Among the mRNA targets of FMRP, three PDEs, PDE1A, PDE2A, and PDE10A, have been identified [116]. The expression of PDE2A in the cortex and hippocampus is negatively modulated by FMRP both on a translational level and by affecting dendritic transport of encoding mRNAs [116]. Consistently, PDE2A expression levels are elevated in Fmr1-KO brains, resulting in reduced levels of both cAMP and cGMP. Treatment of Fmr1-KO mice with Bay 60–7550 normalizes the social and cognitive deficits of infant and adolescent Fmr1-KO mice, increased the maturity of axons and dendritic spines of Fmr1-KO neurons and normalizes the exaggerated hippocampal m-GluR5 long-term depression of Fmr1-KO CA1 [72]. Inhibition of PDE2A activity by Bay 60–7550 rescues the release of synaptic vesicles, which is reduced in the absence of FMRP [117]. Consistently, PDE2A is the only PDE associated with docked vesicles [118]. Collectively these findings suggest the implication of PDE2A in the release of neurotransmitters. Another target of FMRP is the mRNA encoding Pde10a, whose expression is likely increased in the Fmr1-KO mouse brain [116]. Balipodect, an inhibitor of PDE10A, has been accepted by the European Medicine Agency as a potential treatment for FXS (EMADOC-628903358-742). The specific inhibition of PDE4D by BNP14770, a drug developed by Tetra Therapeutics, was shown to be potentially useful for the treatment of FXS. While rolipram—already used to treat FXS animal models [88] inhibits all subtypes of PDE4, BPN14770 is selective for PDE4D. BNP14770 inhibits the enzyme by closing one of the two upstream conserved regions at the regulatory domains across the active site, which limits cAMP access. Daily treatment of Fmr1-KO mice for 14 days with BNP14770 improves social interaction and natural behaviors (such as nesting and marble burying), and rescues the altered dendritic spine morphology of Fmr1-null neurons [119]. The details of two clinical trials for this molecule are shown in Supplementary Table V. Positive results obtained in the phase II clinical trial with BNP14770 and enrolling 30 FXS adult male subjects (age 18–41 years) were recently announced: https://www.fraxa.org/positive-results-reported-in-phase-ii-fragile-x-clinical-trial-of-pde4d-inhibitor-from-tetra-therapeutics/. It was reported that BPN14770 antagonizes the amnesic effects of scopolamine, increases cAMP signaling in the brain, and increases BDNF and markers of neuronal plasticity associated with memory [85]. This might suggest that this drug will be beneficial to other forms of ID and ASD.

ID associated with the coiled-coil and C2 domain-containing 1A (CC2D1A) gene. Functional loss of CC2D1A causes a rare form of autosomal recessive ID, sometimes associated with ASD and seizures [120]. While in Drosophila, the loss of the ortholog of CC2D1A, lgd, is embryonically lethal [121], Cc2d1a conditional KO mice display deficits in neuronal plasticity and in spatial learning and memory, which are accompanied by reduced sociability, hyperactivity, anxiety, and excessive grooming [122]. The CC2D1A gene encodes a transcriptional repressor with essential functions in controlling synapse maturation. This protein regulates the expression of the 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 1A gene in neuronal cells (HTR1A), likely playing a role in the altered regulation of HTR1A, that is known to be associated with SCZ, anxiety, and MDD [123]. CC2D1A is also localized in cytoplasm where it acts as a scaffold protein in the PI3K/PDK1/AKT pathway [124]. CC2D1A is an interactor of PDE4D regulating its activity and thereby fine-tuning cAMP-dependent downstream signaling [125]. Indeed, it regulates CREB activation in hippocampal neurons by increasing PDE4D activity only in male Cc2d1a-deficient mice. Consistently, the male mouse model for CC2D1A-associated disorder shows a deficit in spatial memory that can be restored by inhibiting PDE4D activity. Cc2d1a-deficient female mice do not display this phenotype and pharmacological treatment has no effect on their behavior [125].

RTT is a neurodevelopmental disorder that mostly affects girls (1:10000 newborns). In classical RTT, girls display an apparently normal development for 6–18 months before developing severe phenotypes characterized by language problems, deficits in learning and coordination, stereotypies, sleep disturbances, seizures, and breathing deficiencies. Overall, RTT is considered to have a characteristic clinical course of four stages: (I) early-onset stagnation, (II) developmental regression, (III) pseudostationary period, and (IV) late motor deterioration. RTT is caused by mutations in Methyl CpG binding Protein 2 (MECP2), an X-linked gene encoding a transcription factor that binds methylated DNA and acts both as a repressor and enhancer of transcription [126]. The protein modulates a network of pathways, including the BDNF, PI3K, and ERK pathways [127]. Dysfunction of MECP2 affects morphology and density of dendritic spines, synaptic plasticity, and neuronal migration [126]. Furthermore, reduced cAMP levels were found in neurons of organotypic slices obtained from the brain of a mouse model of RTT due to increased activity of PDE4. Indeed, treatment with rolipram allowed normalization of the growth of neuronal processes and the cAMP transients evoked by electrical stimulation in preBötC neurons [128]. Consistently, reduced levels of CREB and phospho-CREB have been reported in neurons differentiated from human embryonic stem cells and from induced pluripotent stem cells lacking functional MECP2 and displaying an altered arborization. Rolipram rescued these cellular phenotypes as well as several behavioral phenotypes in female RTT mice [129].

Discussion

The results obtained thus far indicate that modulation of PDE activity can be effective for disorders characterized by depressive behavior or memory deficits (Fig. 2) [130, 131]. Clinical trials have mostly addressed the treatment of AD [132] and schizophrenia [133], while two trials are in progress for a form of ASD and only one for depression (Supplementary Table V). We believe that understanding the role of PDE treatment in neurodevelopmental disorders, such as ID, ASD, or both is a very important result obtained from recent studies. Indeed, the pharmacological inhibition of two PDEs (PDE2A and PDE4D) has been associated with multiple autism-like behaviors and cognitive deficit at different ages in mouse models [116, 119, 125]. The inhibition of PDE10A has been proposed for FXS (even if no data have been published yet), ASD [105], and ADHD [106]. The inhibition of PDE3 has been used in DS and is potentially useful for ASD [113]. Indeed, this drug protects against cognitive impairment and white matter disintegration in a mouse model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion [73], a phenotype characterizing some ASD patients [134]. It is also interesting to consider that low cAMP concentrations favor inflammation due to the increase in IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, IL-22, IL-23, tumor necrosis factor-α, γ-interferon, chemokine C–X–C motif ligand 9 (CXCL9), and CXC10 levels [135]. This suggests that PDE inhibitors are thought to have anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects. Increasing experimental evidence supports the presence of neuroinflammation as a relevant element of neurodevelopmental disorders [136, 137]. This indicates the importance of carrying out specific screenings of the expression levels of PDEs in cohorts of patients affected by idiopathic neurodevelopmental diseases such as ASD and/or ID. To achieve this, it could be useful to measure the levels of cAMP and/or cGMP in neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells or in extracellular vesicles from the central nervous system obtained from fibroblasts and blood, respectively, of these patients. The most accurate method to measure the dynamic levels of these second messengers in real-time is represented by the use of specific FRET-based cAMP (or cGMP) biosensors [18, 138]. This could help to establish therapeutic approaches with molecules modulating the activity of specific PDEs.

PDEs involved in various brain disorders so far (Fig. 2) are cAMP-specific, cGMP-specific or have a double target. This can raise the issue whether an altered cAMP/cGMP ratio could represent a pathophysiological element for these diseases. In this context, a good example is provided by the studies on depression showing that phenotypic improvement can be reached by changing the cGMP/cAMP ratio and then, paradoxically, both by increasing cGMP levels or by reducing cAMP levels [56,57,58, 130]. Moreover, also PDEs involved in FXS target both cAMP and cGMP [72, 116, 119] (Fig. 1). Indeed, PDE4 is a cAMP-specific isoform, while both cAMP and cGMP are targets of PDE10A and PDE2A, this latter enzyme being stimulated by cGMP (Fig. 1) [1]. PDE1A is activated by Ca2+ [1] and is involved in FXS [116], a disorder displaying a deregulated Ca2+ homeostasis in brain [139, 140]. We can speculate that an altered cAMP/cGMP ratio is a pathophysiological element in FXS and the modulation of one of those PDEs is sufficient to restore it. This could explain the results in preclinical tests [72, 119] and clinical assays (Supplementary Table V). Thus, it would be difficult to dissect the impact of each PDE in the neurological-psychiatric phenotypes present in FXS. This led to the conclusion that PDE transgenic animals are a main need in the field. Indeed, it is surprising that only a few PDEs have been extensively studied for their impact on brain function by using classical KO animal models. Here, we have reported those models displaying clear psychiatric or neurodevelopmental disorders. In the case of Pde2a, the KO phenotype has never been studied since homozygous mutant mice are not viable [37]. In other cases, a phenotype was not known or was never reported (e.g., PDE5). This latter example is very interesting because pharmacological inhibition of PDE5 resulted in potentiating neurogenesis and memory enhancement [89,90,91,92]. The use of pharmacological preclinical studies is critical to reach the clinical setting but is not enough to understand the role of PDEs during brain development. Indeed, these drugs are administrated only during the post-natal life and often after the weaning, thus missing the possibility to evaluate their impact in early steps of brain development and/or synaptogenesis. Furthermore, genetic silencing of specific PDEs’ variants could allow to study the modulation of cAMP and cGMP abundancy in subcellular compartments (Fig. 2). Studying such a large family of proteins is challenging due to their overlapping functions and because of their actions that are not brain specific. However, tools exist today (e.g., conditional KO and optogenetics) to conduct studies focused on the spatio-temporal role of each PDE in normal and pathological brain development and to elucidate their effects on socio-cognitive behaviors at different ages. These studies should also allow the identification of compensation activities by the various members of the PDE family, as suggested, for instance, by the observation that the expression levels of Pde10a mRNA are elevated in the striatum of Pde1b-KO mice [33].

It is critical that the effects of genes and pathways impacted by the various brain-expressed PDEs be studied in detail in various brain regions and at the synaptic level during brain development. These studies will result in the precise identification of the molecular pathways modulated by each PDE. For instance, an link between PDE3-dependent cAMP signaling with the IGF-1 pathway was established using the specific PDE3 inhibitor cilostazol [76]. Recombinant IGF-1 and some related compounds have emerged as potential therapeutics for the treatment of neurodevelopmental disorders [141]. Trofinetide is a neurotrophic peptide derived from IGF-1 that has a long half-life and is well tolerated. Chronic treatment of Fmr1-KO mice with trofinetide corrects learning and memory deficits, hyperactivity, and social interaction deficits displayed by these animals [142]. Thus, a phase II clinical trial for trofinetide was performed. After only 28 days of treatment, improvements in higher sensory tolerance, reduced anxiety, better self-regulation, and more social engagement were observed (NCT01894958). Interestingly, upon the sponsoring of ACADIA Pharmaceuticals Inc., a phase III clinical trial with trofinetide is in progress in 5–15 years old girls affected by RTT (NCT04181723). On the same way and consistent with previous results linking cAMP with BDNF transcription [143], inhibition of PDEs has been reported to increase BDNF levels [52, 53, 85, 92, 103], whose deregulation is involved in the pathophysiology of depression [144], SCZ [133, 145], RTT [126, 146], and FXS [147]. Therefore, we conclude that these findings support the idea of future therapies for psychiatric disorders at the crossroads of pathways involving cAMP and/or cGMP and neurotrophic factors.

Finally, the surprising results from Zamarbide et al. (CC2D1A) and Tsuji et al. (DS) suggest the possibility that a sex-specific regulation (or deregulation) of cAMP or cGMP levels exists [113, 125]. These findings are particularly important for the treatment of ASD and ID, since the ratio of incidence of this disorder is 3:2 in males vs. females, and this could result in a sex-specific treatment. This possibility should be considered for future studies on PDEs, reinforcing the need to study their relevance for PDE action on brain development and functioning at various ages when sex hormones are present (or not) and they can affect PDE-related pathways differently.

References

Azevedo MF, Faucz FR, Bimpaki E, Horvath A, Levy I, de Alexandre RB, et al. Clinical and molecular genetics of the phosphodiesterases (PDEs). Endocr Rev. 2014;35:195–233.

Steegborn C. Structure, mechanism, and regulation of soluble adenylyl cyclases - similarities and differences to transmembrane adenylyl cyclases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:2535–47.

Potter LR. Guanylyl cyclase structure, function and regulation. Cell Signal. 2011;23:1921–6.

Bender AT, Beavo JA. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular regulation to clinical use. Pharmacol Rev 2006;58:488–520.

Zhang KYJ, Card GL, Suzuki Y, Artis DR, Fong D, Gillette S, et al. A glutamine switch mechanism for nucleotide selectivity by phosphodiesterases. Mol Cell. 2004;15:279–86.

Thul PJ, Åkesson L, Wiking M, Mahdessian D, Geladaki A, Ait Blal H, et al. A subcellular map of the human proteome. Science. 2017;356:eaal3321.

Zeisel A, Hochgerner H, Lönnerberg P, Johnsson A, Memic F, van der Zwan J, et al. Molecular architecture of the mouse nervous system. Cell. 2018;174:999–1014.e22.

Lakics V, Karran EH, Boess FG. Quantitative comparison of phosphodiesterase mRNA distribution in human brain and peripheral tissues. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59:367–74.

Esteban JA, Shi S-H, Wilson C, Nuriya M, Huganir RL, Malinow R. PKA phosphorylation of AMPA receptor subunits controls synaptic trafficking underlying plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:136–43.

Son H, Lu YF, Zhuo M, Arancio O, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. The specific role of cGMP in hippocampal LTP. Learn Mem. 1998;5:231–45.

Banke TG, Bowie D, Lee H, Huganir RL, Schousboe A, Traynelis SF. Control of GluR1 AMPA receptor function by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Neurosci. 2000;20:89–102.

Shelly M, Lim BK, Cancedda L, Heilshorn SC, Gao H, Poo M. Local and long-range reciprocal regulation of cAMP and cGMP in axon/dendrite formation. Science. 2010;327:547–52.

Akiyama H, Fukuda T, Tojima T, Nikolaev VO, Kamiguchi H. Cyclic nucleotide control of microtubule dynamics for axon guidance. J Neurosci. 2016;36:5636–49.

Crawford DC, Mennerick S. Presynaptically silent synapses: dormancy and awakening of presynaptic vesicle release. Neuroscientist. 2012;18:216–23.

Kleppisch T, Feil R. cGMP signalling in the mammalian brain: role in synaptic plasticity and behaviour. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;191:549–79.

Averaimo S, Nicol X. Intermingled cAMP, cGMP and calcium spatiotemporal dynamics in developing neuronal circuits. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:376.

Kumada T, Lakshmana MK, Komuro H. Reversal of neuronal migration in a mouse model of fetal alcohol syndrome by controlling second-messenger signalings. J Neurosci. 2006;26:742–56.

Stoufflet J, Chaulet M, Doulazmi M, Fouquet C, Dubacq C, Métin C, et al. Primary cilium-dependent cAMP/PKA signaling at the centrosome regulates neuronal migration. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaba3992.

Carlezon WA, Duman RS, Nestler EJ. The many faces of CREB. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:436–45.

Portis S, Giunta B, Obregon D, Tan J. The role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 signaling in neurodevelopment and fragile X syndrome. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2012;4:140–8.

Li Z, Theus MH, Wei L. Role of ERK 1/2 signaling in neuronal differentiation of cultured embryonic stem cells. Dev Growth Differ. 2006;48:513–23.

Albert-Gascó H, Ros-Bernal F, Castillo-Gómez E, Olucha-Bordonau FE. MAP/ERK signaling in developing cognitive and emotional function and its effect on pathological and neurodegenerative processes. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:4471.

Spilker C, Kreutz MR. RapGAPs in brain: multipurpose players in neuronal Rap signalling. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32:1–9.

Zhong J. RAS and downstream RAF-MEK and PI3K-AKT signaling in neuronal development, function and dysfunction. Biol Chem. 2016;397:215–22.

Lee JJ, Wedow R, Okbay A, Kong E, Maghzian O, Zacher M, et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1112–21.

Gurney ME. Genetic association of phosphodiesterases with human cognitive performance. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:22.

Sharma RK, Wang JH. Purification and characterization of bovine lung calmodulin-dependent cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. An enzyme containing calmodulin as a subunit. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:14160–6.

Autism Spectrum Disorders Working Group of The Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Meta-analysis of GWAS of over 16,000 individuals with autism spectrum disorder highlights a novel locus at 10q24.32 and a significant overlap with schizophrenia. Mol Autism. 2017;8:21.

De Rubeis S, He X, Goldberg AP, Poultney CS, Samocha K, Cicek AE, et al. Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature. 2014;515:209–15.

John J, Bhattacharyya U, Yadav N, Kukshal P, Bhatia T, Nimgaonkar VL, et al. Multiple rare inherited variants in a four generation schizophrenia family offer leads for complex mode of disease inheritance. Schizophrenia Res. 2020;216:S288–294.

McQuown S, Xia S, Baumgärtel K, Barido R, Anderson G, Dyck B, et al. Phosphodiesterase 1b (PDE1B) regulates spatial and contextual memory in hippocampus. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:21.

Reed TM, Repaske DR, Snyder GL, Greengard P, Vorhees CV. Phosphodiesterase 1B knock-out mice exhibit exaggerated locomotor hyperactivity and DARPP-32 phosphorylation in response to dopamine agonists and display impaired spatial learning. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5188–97.

Hufgard JR, Williams MT, Skelton MR, Grubisha O, Ferreira FM, Sanger H, et al. Phosphodiesterase-1b (Pde1b) knockout mice are resistant to forced swim and tail suspension induced immobility and show upregulation of Pde10a. Psychopharmacology. 2017;234:1803–13.

Haidar Z, Jalkh N, Corbani S, Abou-Ghoch J, Fawaz A, Mehawej C, et al. A homozygous splicing mutation in PDE2A in a family with atypical Rett syndrome. Mov Disord. 2020;35:896–9.

Salpietro V, Perez-Dueñas B, Nakashima K, San Antonio-Arce V, Manole A, Efthymiou S, et al. A homozygous loss-of-function mutation in PDE2A associated to early-onset hereditary chorea. Mov Disord. 2018;33:482–8.

Farmer R, Burbano SD, Patel NS, Sarmiento A, Smith AJ, Kelly MP. Phosphodiesterases PDE2A and PDE10A both change mRNA expression in the human brain with age, but only PDE2A changes in a region-specific manner with psychiatric disease. Cell Signal. 2020;70:109592.

Assenza MR, Barbagallo F, Barrios F, Cornacchione M, Campolo F, Vivarelli E, et al. Critical role of phosphodiesterase 2A in mouse congenital heart defects. Cardiovasc Res. 2018;114:830–45.

Richter W, Menniti FS, Zhang H-T, Conti M. PDE4 as a target for cognition enhancement. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2013;17:1011–27.

Byers D, Davis RL, Kiger JA. Defect in cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase due to the dunce mutation of learning in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 1981;289:79–81.

Gervasi N, Tchénio P, Preat T. PKA dynamics in a Drosophila learning center: coincidence detection by rutabaga adenylyl cyclase and spatial regulation by dunce phosphodiesterase. Neuron. 2010;65:516–29.

Millar JK, Pickard BS, Mackie S, James R, Christie S, Buchanan SR, et al. DISC1 and PDE4B are interacting genetic factors in schizophrenia that regulate cAMP signaling. Science. 2005;310:1187–91.

Pickard BS, Thomson PA, Christoforou A, Evans KL, Morris SW, Porteous DJ, et al. The PDE4B gene confers sex-specific protection against schizophrenia. Psychiatr Genet. 2007;17:129–33.

Malakhova AV, Rudko OI, Sobolev VV, Tretiakov AV, Naumova EA, Kokaeva ZG, et al. PDE4B gene polymorphism in Russian patients with panic disorder. AIMS Genet. 2019;6:55–63.

Siuciak JA, Chapin DS, McCarthy SA, Martin AN. Antipsychotic profile of rolipram: efficacy in rats and reduced sensitivity in mice deficient in the phosphodiesterase-4B (PDE4B) enzyme. Psychopharmacology. 2007;192:415–24.

Rutten K, Wallace TL, Works M, Prickaerts J, Blokland A, Novak TJ, et al. Enhanced long-term depression and impaired reversal learning in phosphodiesterase 4B-knockout (PDE4B-/-) mice. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:138–47.

Zhang H-T, Huang Y, Masood A, Stolinski LR, Li Y, Zhang L, et al. Anxiogenic-like behavioral phenotype of mice deficient in phosphodiesterase 4B (PDE4B). Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1611–23.

Linglart A, Fryssira H, Hiort O, Holterhus P-M, Perez de Nanclares G, Argente J, et al. PRKAR1A and PDE4D mutations cause acrodysostosis but two distinct syndromes with or without GPCR-signaling hormone resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2328–38.

Michot C, Le Goff C, Blair E, Blanchet P, Capri Y, Gilbert-Dussardier B, et al. Expanding the phenotypic spectrum of variants in PDE4D/PRKAR1A: from acrodysostosis to acroscyphodysplasia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2018;26:1611–22.

Zhang H-T, Huang Y, Jin S-L, Frith SA, Suvarna N, Conti M, et al. Antidepressant-like profile and reduced sensitivity to rolipram in mice deficient in the PDE4D phosphodiesterase enzyme. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:587–95.

Siuciak JA, McCarthy SA, Chapin DS, Martin AN, Harms JF, Schmidt CJ. Behavioral characterization of mice deficient in the phosphodiesterase-10A (PDE10A) enzyme on a C57/Bl6N congenic background. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:417–27.

Cardinale A, Fusco FR. Inhibition of phosphodiesterases as a strategy to achieve neuroprotection in Huntington’s disease. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24:319–28.

Nthenge-Ngumbau DN, Mohanakumar KP. Can cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase inhibitors be drugs for Parkinson’s disease? Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55:822–34.

Bollen E, Prickaerts J. Phosphodiesterases in neurodegenerative disorders. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:965–70.

Kelly MP, Logue SF, Brennan J, Day JP, Lakkaraju S, Jiang L, et al. Phosphodiesterase 11A in brain is enriched in ventral hippocampus and deletion causes psychiatric disease-related phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8457–62.

Kelly MP. A role for phosphodiesterase 11A (PDE11A) in the formation of social memories and the stabilization of mood. Adv Neurobiol. 2017;17:201–30.

Luo H-R, Wu G-S, Dong C, Arcos-Burgos M, Ribeiro L, Licinio J, et al. Association of PDE11A global haplotype with major depression and antidepressant drug response. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:163–70.

Reierson GW, Mastronardi CA, Licinio J, Wong M-L. Chronic imipramine downregulates cyclic AMP signaling in rat hippocampus. Neuroreport. 2009;20:307–11.

Reierson GW, Mastronardi CA, Licinio J, Wong M-L. Repeated antidepressant therapy increases cyclic GMP signaling in rat hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 2009;466:149–53.

Enomoto T, Tatara A, Goda M, Nishizato Y, Nishigori K, Kitamura A, et al. A novel phosphodiesterase 1 inhibitor DSR-141562 exhibits efficacies in animal models for positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms associated with schizophrenia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2019;371:692–702.

Liu L, Zheng J, Huang X-F, Zhu X, Ding S-M, Ke H-M, et al. The neuroprotective and antidepressant-like effects of Hcyb1, a novel selective PDE2 inhibitor. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24:652–60.

Nakashima M, Imada H, Shiraishi E, Ito Y, Suzuki N, Miyamoto M, et al. Phosphodiesterase 2A inhibitor TAK-915 ameliorates cognitive impairments and social withdrawal in N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist-induced rat models of schizophrenia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2018;365:179–88.

Nakashima M, Suzuki N, Shiraishi E, Iwashita H. TAK-915, a phosphodiesterase 2A inhibitor, ameliorates the cognitive impairment associated with aging in rodent models. Behav Brain Res. 2019;376:112192.

Wang J-N, Zhao X-J, Liu Z-H, Zhao X-L, Sun T, Fu Z-J. Selective phosphodiesterase-2A inhibitor alleviates radicular inflammation and mechanical allodynia in non-compressive lumbar disc herniation rats. Eur Spine J. 2017;26:1961–8.

Boess FG, Hendrix M, van der Staay F-J, Erb C, Schreiber R, van Staveren W, et al. Inhibition of phosphodiesterase 2 increases neuronal cGMP, synaptic plasticity and memory performance. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:1081–92.

Domek-Łopacińska K, Strosznajder JB. The effect of selective inhibition of cyclic GMP hydrolyzing phosphodiesterases 2 and 5 on learning and memory processes and nitric oxide synthase activity in brain during aging. Brain Res. 2008;1216:68–77.

Bollen E, Akkerman S, Puzzo D, Gulisano W, Palmeri A, D’Hooge R, et al. Object memory enhancement by combining sub-efficacious doses of specific phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Neuropharmacology. 2015;95:361–6.

Ruan L, Du K, Tao M, Shan C, Ye R, Tang Y, et al. Phosphodiesterase-2 Inhibitor Bay 60-7550 ameliorates Aβ-induced cognitive and memory impairment via regulation of the HPA axis. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:432.

Soares LM, Meyer E, Milani H, Steinbusch HWM, Prickaerts J, de Oliveira RMW. The phosphodiesterase type 2 inhibitor BAY 60-7550 reverses functional impairments induced by brain ischemia by decreasing hippocampal neurodegeneration and enhancing hippocampal neuronal plasticity. Eur J Neurosci. 2017;45:510–20.

Shi J, Liu H, Pan J, Chen J, Zhang N, Liu K, et al. Inhibition of phosphodiesterase 2 by Bay 60-7550 decreases ethanol intake and preference in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235:2377–85.

Reneerkens OAH, Rutten K, Bollen E, Hage T, Blokland A, Steinbusch HWM, et al. Inhibition of phoshodiesterase type 2 or type 10 reverses object memory deficits induced by scopolamine or MK-801. Behav Brain Res. 2013;236:16–22.

Wang L, Xiaokaiti Y, Wang G, Xu X, Chen L, Huang X, et al. Inhibition of PDE2 reverses beta amyloid induced memory impairment through regulation of PKA/PKG-dependent neuro-inflammatory and apoptotic pathways. Sci Rep. 2017;7:12044.

Maurin T, Melancia F, Jarjat M, Castro L, Costa L, Delhaye S, et al. Involvement of phosphodiesterase 2A activity in the pathophysiology of fragile X syndrome. Cereb Cortex. 2019;29:3241–52.

Kitamura A, Manso Y, Duncombe J, Searcy J, Koudelka J, Binnie M, et al. Long-term cilostazol treatment reduces gliovascular damage and memory impairment in a mouse model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4299.

Tai S-Y, Chien C-Y, Chang Y-H, Yang Y-H. Cilostazol use is associated with reduced risk of dementia: a nationwide cohort study. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14:784–91.

Tai S-Y, Chen C-H, Chien C-Y, Yang Y-H. Cilostazol as an add-on therapy for patients with Alzheimer’s disease in Taiwan: a case control study. BMC Neurol. 2017;17:40.

Zhao J, Harada N, Kurihara H, Nakagata N, Okajima K. Cilostazol improves cognitive function in mice by increasing the production of insulin-like growth factor-I in the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:774–83.

Zheng W-H, Quirion R. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) induces the activation/phosphorylation of Akt kinase and cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) by activating different signaling pathways in PC12 cells. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:51.

Blokland A, Van Duinen MA, Sambeth A, Heckman PRA, Tsai M, Lahu G, et al. Acute treatment with the PDE4 inhibitor roflumilast improves verbal word memory in healthy old individuals: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;77:37–43.

Gilleen J, Farah Y, Davison C, Kerins S, Valdearenas L, Uz T, et al. An experimental medicine study of the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, roflumilast, on working memory-related brain activity and episodic memory in schizophrenia patients. Psychopharmacology. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-018-5134-y.

Zhong Q, Yu H, Huang C, Zhong J, Wang H, Xu J, et al. FCPR16, a novel phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, produces an antidepressant-like effect in mice exposed to chronic unpredictable mild stress. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;90:62–75.

Monti B, Berteotti C, Contestabile A. Subchronic Rolipram delivery activates hippocampal CREB and Arc, enhances retention and slows down extinction of conditioned fear. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006;31:278–86.

Wimmer ME, Blackwell JM, Abel T. Rolipram treatment during consolidation ameliorates long-term object location memory in aged male mice. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2020;169:107168.

Xu Y, Zhu N, Xu W, Ye H, Liu K, Wu F, et al. Inhibition of phosphodiesterase-4 reverses Aβ-induced memory impairment by regulation of HPA axis related cAMP signaling. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:204.

Cui S-Y, Yang M-X, Zhang Y-H, Zheng V, Zhang H-T, Gurney ME, et al. Protection from amyloid β peptide-induced memory, biochemical, and morphological deficits by a phosphodiesterase-4D allosteric inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2019;371:250–9.

Zhang C, Xu Y, Chowdhary A, Fox D, Gurney ME, Zhang H-T, et al. Memory enhancing effects of BPN14770, an allosteric inhibitor of phosphodiesterase-4D, in wild-type and humanized mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:2299–309.

Bourtchouladze R, Lidge R, Catapano R, Stanley J, Gossweiler S, Romashko D, et al. A mouse model of Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome: defective long-term memory is ameliorated by inhibitors of phosphodiesterase 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10518–22.

Wiescholleck V, Manahan-Vaughan D. PDE4 inhibition enhances hippocampal synaptic plasticity in vivo and rescues MK801-induced impairment of long-term potentiation and object recognition memory in an animal model of psychosis. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e89.

Choi CH, Schoenfeld BP, Weisz ED, Bell AJ, Chambers DB, Hinchey J, et al. PDE-4 inhibition rescues aberrant synaptic plasticity in Drosophila and mouse models of fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci. 2015;35:396–408.

Zhang R, Wang Y, Zhang L, Zhang Z, Tsang W, Lu M, et al. Sildenafil (Viagra) induces neurogenesis and promotes functional recovery after stroke in rats. Stroke. 2002;33:2675–80.

Prickaerts J, van Staveren WCG, Sik A, Markerink-van Ittersum M, Niewöhner U, van der Staay FJ, et al. Effects of two selective phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, sildenafil and vardenafil, on object recognition memory and hippocampal cyclic GMP levels in the rat. Neuroscience. 2002;113:351–61.

Devan BD, Bowker JL, Duffy KB, Bharati IS, Jimenez M, Sierra-Mercado D, et al. Phosphodiesterase inhibition by sildenafil citrate attenuates a maze learning impairment in rats induced by nitric oxide synthase inhibition. Psychopharmacology. 2006;183:439–45.

Sanders O. Sildenafil for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2020;4:91–106.

Schultheiss D, Müller SV, Nager W, Stief CG, Schlote N, Jonas U, et al. Central effects of sildenafil (Viagra) on auditory selective attention and verbal recognition memory in humans: a study with event-related brain potentials. World J Urol. 2001;19:46–50.

Huang X-F, Jiang W-T, Liu L, Song F-C, Zhu X, Shi G-L, et al. A novel PDE9 inhibitor WYQ-C36D ameliorates corticosterone-induced neurotoxicity and depression-like behaviors by cGMP-CREB-related signaling. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24:889–96.

Kleiman RJ, Chapin DS, Christoffersen C, Freeman J, Fonseca KR, Geoghegan KF, et al. Phosphodiesterase 9A regulates central cGMP and modulates responses to cholinergic and monoaminergic perturbation in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;341:396–409.

Frölich L, Wunderlich G, Thamer C, Roehrle M, Garcia M, Dubois B. Evaluation of the efficacy, safety and tolerability of orally administered BI 409306, a novel phosphodiesterase type 9 inhibitor, in two randomised controlled phase II studies in patients with prodromal and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11:18.

Schwam EM, Nicholas T, Chew R, Billing CB, Davidson W, Ambrose D, et al. A multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the PDE9A inhibitor, PF-04447943, in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2014;11:413–21.

Chakroborty S, Manfredsson FP, Dec AM, Campbell PW, Stutzmann GE, Beaumont V, et al. Phosphodiesterase 9A inhibition facilitates corticostriatal transmission in wild-type and transgenic rats that model Huntington’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:466.

Suzuki K, Harada A, Shiraishi E, Kimura H. In vivo pharmacological characterization of TAK-063, a potent and selective phosphodiesterase 10A inhibitor with antipsychotic-like activity in rodents. J Pharmpacol Exp Ther. 2015;352:471–9.

Takakuwa M, Watanabe Y, Tanaka K, Ishii T, Kagaya K, Taniguchi H, et al. Antipsychotic-like effects of a novel phosphodiesterase 10A inhibitor T-251 in rodents. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2019;185:172757.

Macek TA, McCue M, Dong X, Hanson E, Goldsmith P, Affinito J, et al. A phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of TAK-063 in subjects with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Res. 2019;204:289–94.

Cheng Y, Wang Z-M, Tan W, Wang X, Li Y, Bai B, et al. Partial loss of psychiatric risk gene miR-137 in mice causes repetitive behavior and impairs sociability and learning via increased Pde10a. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:1689–703.

Giralt A, Saavedra A, Carretón O, Arumí H, Tyebji S, Alberch J, et al. PDE10 inhibition increases GluA1 and CREB phosphorylation and improves spatial and recognition memories in a Huntington’s disease mouse model. Hippocampus. 2013;23:684–95.

Guang S, Pang N, Deng X, Yang L, He F, Wu L, et al. Synaptopathology involved in autism spectrum disorder. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:470.

Luhach K, Kulkarni GT, Singh VP, Sharma B. Attenuation of neurobehavioural abnormalities by papaverine in prenatal valproic acid rat model of ASD. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020:173663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173663

Sharma N, Dhiman N, Golani LK, Sharma B. Papaverine ameliorates prenatal alcohol-induced experimental attention deficit hyperactivity disorder by regulating neuronal function, inflammation, and oxidative stress. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2020; https://doi.org/10.1002/jdn.10076.

Antonarakis SE, Skotko BG, Rafii MS, Strydom A, Pape SE, Bianchi DW, et al. Down syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2020;6:9.

De Toma I, Ortega M, Aloy P, Sabidó E, Dierssen M. DYRK1A overexpression alters cognition and neural-related proteomic pathways in the hippocampus that are rescued by green tea extract and/or environmental enrichment. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:272.

van Bon BWM, Coe BP, Bernier R, Green C, Gerdts J, Witherspoon K, et al. Disruptive de novo mutations of DYRK1A lead to a syndromic form of autism and ID. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:126–32.

Yang EJ, Ahn YS, Chung KC. Protein kinase Dyrk1 activates cAMP response element-binding protein during neuronal differentiation in hippocampal progenitor cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39819–24.

Lott IT, Head E. Dementia in Down syndrome: unique insights for Alzheimer disease research. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:135–47.

Dierssen M, Vallina IF, Baamonde C, García-Calatayud S, Lumbreras MA, Flórez J. Alterations of central noradrenergic transmission in Ts65Dn mouse, a model for Down syndrome. Brain Res. 1997;749:238–44.

Tsuji M, Ohshima M, Yamamoto Y, Saito S, Hattori Y, Tanaka E, et al. Cilostazol, a phosphodiesterase 3 inhibitor, moderately attenuates behaviors depending on sex in the Ts65Dn mouse model of down syndrome. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:106.

Dahlhaus R. Of men and mice: modeling the fragile X syndrome. Front Mol Neurosci 2018;11:41.

Berry-Kravis E, Huttenlocher PR. Cyclic AMP metabolism in fragile X syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1992;31:22–26.

Maurin T, Lebrigand K, Castagnola S, Paquet A, Jarjat M, Popa A, et al. HITS-CLIP in various brain areas reveals new targets and new modalities of RNA binding by fragile X mental retardation protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:6344–55.

García-Font N, Martín R, Torres M, Oset-Gasque MJ, Sánchez-Prieto J. The loss of β adrenergic receptor mediated release potentiation in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;130:104482.

Boyken J, Grønborg M, Riedel D, Urlaub H, Jahn R, Chua JJE. Molecular profiling of synaptic vesicle docking sites reveals novel proteins but few differences between glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses. Neuron. 2013;78:285–97.

Gurney ME, Cogram P, Deacon RM, Rex C, Tranfaglia M. Multiple behavior phenotypes of the fragile-X syndrome mouse model respond to chronic inhibition of phosphodiesterase-4D (PDE4D). Sci Rep. 2017;7:14653.

Manzini MC, Xiong L, Shaheen R, Tambunan DE, Di Costanzo S, Mitisalis V, et al. CC2D1A regulates human intellectual and social function as well as NF-κB signaling homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2014;8:647–55.

Gallagher CM, Knoblich JA. The conserved c2 domain protein lethal (2) giant discs regulates protein trafficking in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2006;11:641–53.

Oaks AW, Zamarbide M, Tambunan DE, Santini E, Di Costanzo S, Pond HL, et al. Cc2d1a Loss of function disrupts functional and morphological development in forebrain neurons leading to cognitive and social deficits. Cereb Cortex. 2017;27:1670–85.

Guan F, Lin H, Chen G, Li L, Chen T, Liu X, et al. Evaluation of association of common variants in HTR1A and HTR5A with schizophrenia and executive function. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38048.

Al-Tawashi A, Gehring C. Phosphodiesterase activity is regulated by CC2D1A that is implicated in non-syndromic intellectual disability. Cell Commun Signal. 2013;11:47.

Zamarbide M, Mossa A, Muñoz-Llancao P, Wilkinson MK, Pond HL, Oaks AW, et al. Male-specific cAMP signaling in the hippocampus controls spatial memory deficits in a mouse model of autism and intellectual disability. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85:760–8.

Lombardi LM, Baker SA, Zoghbi HY. MECP2 disorders: from the clinic to mice and back. J Clin Investig. 2015;125:2914–23.

Sanfeliu A, Kaufmann WE, Gill M, Guasoni P, Tropea D. Transcriptomic studies in mouse models of Rett syndrome: a review. Neuroscience. 2019;413:183–205.

Mironov SL, Skorova EY, Kügler S. Epac-mediated cAMP-signalling in the mouse model of Rett Syndrome. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:869–77.

Bu Q, Wang A, Hamzah H, Waldman A, Jiang K, Dong Q, et al. CREB Signaling Is Involved in Rett Syndrome Pathogenesis. J Neurosci. 2017;37:3671–85.

Esposito K, Reierson GW, Luo HR, Wu GS, Licinio J, Wong M-L. Phosphodiesterase genes and antidepressant treatment response: a review. Ann Med. 2009;41:177–85.

Blokland A, Schreiber R, Prickaerts J. Improving memory: a role for phosphodiesterases. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:2511–23.

Prickaerts J, Heckman PRA, Blokland A. Investigational phosphodiesterase inhibitors in phase I and phase II clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26:1033–48.

Heckman PRA, Blokland A, Ramaekers J, Prickaerts J. PDE and cognitive processing: beyond the memory domain. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2015;119:108–22.

Bjørklund G, Kern JK, Urbina MA, Saad K, El-Houfey AA, Geier DA, et al. Cerebral hypoperfusion in autism spectrum disorder. Acta Neurobiol Exp. 2018;78:21–29.

Pieretti S, Dominici L, Di Giannuario A, Cesari N, Dal Piaz V. Local anti-inflammatory effect and behavioral studies on new PDE4 inhibitors. Life Sci. 2006;79:791–800.

Matta SM, Hill-Yardin EL, Crack PJ. The influence of neuroinflammation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;79:75–90.

Hagberg H, Mallard C, Ferriero DM, Vannucci SJ, Levison SW, Vexler ZS, et al. The role of inflammation in perinatal brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:192–208.

Zaccolo M, Cesetti T, Di Benedetto G, Mongillo M, Lissandron V, Terrin A, et al. Imaging the cAMP-dependent signal transduction pathway. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:1323–6.

Ferron L. Fragile X mental retardation protein controls ion channel expression and activity. J Physiol. 2016;594:5861–7.

Castagnola S, Cazareth J, Lebrigand K, Jarjat M, Magnone V, Delhaye S, et al. Agonist-induced functional analysis and cell sorting associated with single-cell transcriptomics characterizes cell subtypes in normal and pathological brain. Genome Res. 2020;30:1633–42.

Wrigley S, Arafa D, Tropea D. Insulin-like growth factor 1: at the crossroads of brain development and aging. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:14.

Deacon RMJ, Glass L, Snape M, Hurley MJ, Altimiras FJ, Biekofsky RR, et al. NNZ-2566, a novel analog of (1-3) IGF-1, as a potential therapeutic agent for fragile X syndrome. Neuromolecular Med. 2015;17:71–82.

Esvald E-E, Tuvikene J, Sirp A, Patil S, Bramham CR, Timmusk T. CREB family transcription factors are major mediators of BDNF transcriptional autoregulation in cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2020;40:1405–26.

Björkholm C, Monteggia LM. BDNF—a key transducer of antidepressant effects. Neuropharmacology. 2016;102:72–79.

Libman-Sokołowska M, Drozdowicz E, Nasierowski T. BDNF as a biomarker in the course and treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Pol. 2015;49:1149–58.

Downs J, Rodger J, Li C, Tan X, Hu N, Wong K, et al. Environmental enrichment intervention for Rett syndrome: an individually randomised stepped wedge trial. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13:3.

Nomura T, Musial TF, Marshall JJ, Zhu Y, Remmers CL, Xu J, et al. Delayed maturation of fast-spiking interneurons is rectified by activation of the TrkB receptor in the mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci. 2017;37:11298–310.

Wang P, Wu P, Egan RW, Billah MM. Identification and characterization of a new human type 9 cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase splice variant (PDE9A5): differential tissue distribution and subcellular localization of PDE9A variants. Gene. 2003;314:15–27.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Inserm, CNRS, Université Côte d’Azur, Féderation Recherche sur le Cerveau, Fondation Jérôme Lejeune, and Agence Nationale de la Recherche: ANR-20-CE16-0016 and ANR-15-IDEX-0001. The authors are grateful to M. Capovilla, E. Lalli, T. Maurin, and D. Tropea for critical reading of the manuscript and discussion and they are indebted to F. Aguila for graphical artwork.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Delhaye, S., Bardoni, B. Role of phosphodiesterases in the pathophysiology of neurodevelopmental disorders. Mol Psychiatry 26, 4570–4582 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-00997-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-00997-9

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Beyond traditional pharmacology: evaluating phosphodiesterase inhibitors in autism spectrum disorder

Neuropsychopharmacology (2024)

-

Erythropoietin restrains the inhibitory potential of interneurons in the mouse hippocampus

Molecular Psychiatry (2024)

-

Cilostazol pretreatment prevents PTSD-related anxiety behavior through reduction of hippocampal neuroinflammation

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (2024)

-

Role of interaction mode of phenanthrene derivatives as selective PDE5 inhibitors using molecular dynamics simulations and quantum chemical calculations

Molecular Diversity (2024)

-

The Lack of Alterations in Metabolites in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex and Amygdala, but Their Associations with Autistic Traits, Empathy, and Personality Traits in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Preliminary Study

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2024)