Abstract

Anthropogenic phosphorus (P) input from fertilised and unfertilised topsoils into surface water and re-dissolution from sediments can be key drivers of eutrophication. This study aimed to (1) analyse the P input processes into streams/rivers particularly via erosion from fertilised and unfertilised fields and (2) study the effectiveness of the riparian strip in reducing P emissions from diffuse sources. For the investigation, Cambisol-Tschernosem and Luvisol samples from Loess were taken from Thuringian test fields (Germany). Three laboratory simulations were designed to analyse P re-dissolution and leaching behaviour from topsoils and sediments and further extrapolated to a realistic scenario based on the P input path into receiving waters via erosion. Organic bonded phosphorus and orthophosphate were leached out at the beginning. Upscaling to a realistic scenario showed that the main source of P in receiving waters was leaching from sediment interstitial sites (57.5%) via percolation while the P re-dissolution via diffusion (13%), due to two heavy rain events (17%), and leaching from soil interstitial sites (12.5%) only played a minor role. The risk of eutrophication exceeded the threshold total P of 0.10 mg L-1 given as an orientation value by the Federal/State water consortium (LAWA). This was observed in percolates from all sandy soils (0.17–0.85 mg L-1), only slightly in the clayey soils (≤ 0.11 mg L-1) but not in either streambed sediment (≤ 0.08 mg L-1). However, local differences such as steeper slope, different soil compositions such as higher sand and lower clay percentages, and poorer buffering due to lower lime and aluminium content were identified as reasons for a higher risk of eutrophication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Phosphorus (P) is an essential and non-substitutable element for all life on Earth and a vital component of agricultural fertiliser; however, an increased release of P can have a negative environmental impact. Around 40 million tons of mineral phosphate is used in agriculture every year worldwide (Killiches et al. 2013; Stürmer and Waltner 2021). In the 1950s, when the intensive and excessive use of industrial produced fertilisers in Germany began, increased concentrations of P and nitrogen (N) were observed in surface waters, caused by agricultural runoff (Glibert et al. 2005). Diffuse P sources such as leaching from soils and sediments are alongside point sources the reason for anthropogenically caused eutrophication (Tetzlaff et al. 2017). Eutrophication triggers algae growth which means more biomass input into the aqueous environment (Seppälä et al. 2004). Microorganisms metabolise dead biomass, consuming oxygen which can be followed by a change from aerobic to anaerobic conditions. Consequently, a high number of aquatic organisms die due to lack of oxygen. To better understand P mobility in soils and sediments, and therefore the harm of this nutrient for surface waters, sorption/dissolution processes of P need to be better understood.

P mobility in soils and sediments is influenced by several environmental factors. Riddle et al. (2018) found that Swedish organic and mineral arable soils pose a eutrophication risk with 0–20 cm soil depth leaching the most P (2.1–10.3 mg L-1) following four simulated rainfall events (5 mm h-1). Heavy rain events cause soil erosion which may introduce P-loaded soils into surface waters. If P is associated with iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), aluminum (Al), calcium (Ca), and/or organic matter, its mobility may be reduced (Blume et al. 2016; Echterhoff and Meißner 2015; Holtan et al. 1988; Zorn 1998). Less mobile forms of P have a lower eutrophication potential, which also depends on grain size and soil composition. The sorption process of P leads to a short-term immobilisation and thus the soil/sediment acts as a temporary P sink. However, changes in conditions such as oxygen concentration, redox potential, temperature, or pH may mobilise the P so that re-dissolution processes occur (Holtan et al. 1988). The most common aqueous dissolved form of P is ortho-phosphate (o-PO43-), which contributes to eutrophication of surface waters.

A powerful tool to reduce diffuse P emissions into surface waters, particularly via erosion, is an unfertilised piece of land between agricultural land and receiving water (riparian strip) which was introduced by federal law (Water Resources Act (WHG)) in Germany on 19/06/2020 (Dannemann 2015; Wasserhaushaltsgesetz (WHG) 2020). For this natural buffer system, the width, soil type, slope, and type of cultivation are key to ensure a great effectiveness in reducing P emissions (Fürstenau and Harzendorf 2016). Zhang et al. (2010) found that a buffer between field and surface waters reduces the sediment export by 51–100%, depending on width and vegetation type. As such, riparian strips can be used to reduce P emission into surface waters. They observed for a 5 m riparian strip a retention increase of 29% for P and of 14% for N using trees only compared to a mixed use of grass and trees. The same study showed that the peak of retention effectiveness of sediments was reached at a riparian strip width of 10 m. Compared to the 10 m riparian strip, a 20 m riparian strip enhanced the retention effectiveness by about 20% for P and N.

Only about 10% of Thuringian surface waters are in the “good condition” required by the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD) (The European parliament and the council of the European union 2000), which shows an urgent need for action (Siegesmund 2019). 52% of all P emissions into surface waters in Thuringia are caused by diffuse sources, mainly due to erosion processes (34%) but also interflow (10%) and other sources (8%) (Tetzlaff et al. 2017). However, information regarding P input processes into receiving waters from diffuse sources such as agriculture is lacking. Our study objective was to investigate the agricultural P input processes into receiving waters at the laboratory scale. Three simulations were created to determine P re-dissolution processes in topsoils and sediments and to estimate erosion, diffusion, and interflow through soil interstitial sites on P input to streams. A further aim was to study the effectiveness of riparian strip in reducing P emissions from diffuse sources. A better understanding of these processes will allow better informed use of fertilisers which reduces the risk of eutrophication, preserves our P stocks, and is more economical for the agriculture industry.

2 Material and Methods

2.1 Sampling areas and River Basins

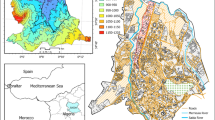

Samples were taken from Friemar (Cambisol-Tschernosem from Loess) and Großenstein (Luvisol from Loess), both in Thuringia (Central Germany) (Fig. 1). The selected samples represent the most common agricultural soil types in this region which contribute considerably to P introduction into surface waters. This allows both clayey (Cambisol-Tschernosem) and sandy (Luvisol) soils to be studied and compared. From each study site, six samples were taken: three topsoil samples with different levels of fertilisation (no fertilisation, optimum and -30% of optimum); two topsoil samples from the area next to a nearby stream (“Hillside” and “Riparian strip”); and one sediment sample from the streambed. All topsoil samples (0–25 cm) were taken randomly at each study site and mixed on site. Samples Soil 1–4 from both study sites are quadruplicates from four sections (a, b, c, and d) of the test fields run by Thuringian State Office for Agriculture and Rural Areas (TLLLR). The samples from study site Großenstein were taken on 23/03/2020 and from study site Friemar on 26/03/2020. The last time the test fields were fertilised before sampling was 08/08/2019 in Friemar and 15/11/2019 in Großenstein (Supplementary material (SM), Table S 1).

Sampling areas and river basins for study site Friemar (Cambisol-Tschernosem from Loess, Weser catchment) and for study site Großenstein (Luvisol from Loess, Elbe catchment) shown in Germany (a). Sampling and nearby gauging stations with river basins for Friemar and Großenstein shown in Thuringia (b). Exact sampling position at Friemar (c). Exact sampling positions at Großenstein (d). Created using software ArcGIS Desktop 10.7.1 from ESRI Deutschland GmbH (Kranzberg, Germany), ©TLLLR

2.2 Method Validation

Method validation for P was carried out using inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) SPECTRO ARCOS (SPECTRO Analytical Instruments GmbH, Germany) as total P (SM, Table S 2) and for flow injection analysis (FIA) QuikChem 8500 (Lachat Instruments, USA) as inorganic PO43- (SM, Table S 3). The scope of the validation included the following eight parameters: (1) Selectivity, specificity, (2) Limit of Detection/Quantification, (3) Working range / linear range, (4) Recovery, (5) Sensitivity, (6) Measurement precision, (7) Repeatability/reproducibility, and (8) Robustness. All results are listed in the supplementary material (S 1). The conclusion of the method validation was that the methods used are adequate for the questions to be answered.

2.3 Sample Preparation and Analysis

All samples were dried (40 °C), sieved (< 2 mm) (JEHMLICH BSM 53,870, Nossen, Germany), and used for all experiments to ensure comparable conditions (grain sizes and soil/sediment characterisation: Table 1‒Table 3). For standards and working solutions, deionised high purity water (> 18.2 MΩ ∙ cm, UV lamp, pH = 6.0, T = 26 °C) (GenPure, TKA Wasseraufbereitungssysteme GmbH, Germany) was used throughout. Soil composition (Köhn-pipette (DIN ISO 11277:2020–04)) and some basic parameters such as pH (Type: senTix® 81, WTW GmbH, Weilheim, Germany), element composition, and P content (Totals: X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy from ash, S8 TIGER, Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany; Pseudo totals: Aqua regia extraction, ICP-OES) were analysed by TLLLR (Table 1‒Table 2). XRF spectroscopy represents the total element content while the pseudo total element content does not include silicate-bonded P which is indeed not as important from an ecological point of view. Therefore, the term “P-pool” is used for the P pseudo total content in the following text. The plant available P was determined using the Calcium-Acetate-Lactate (CAL) method. In addition, the most likely elements to associate with P (Al, Ca, Fe, and Mn) were measured in all experiments using ICP-OES (Blume et al. 2016; Echterhoff and Meißner 2015; Holtan et al. 1988; Zorn 1998) (SM, Table S 2).

2.4 Laboratory Simulations

Three different experiments (described in detail in subsections 2.4.1‒2.4.3) were performed to investigate the dynamics of P input processes into receiving waters. In all soil experiments, deionised water (simulating rain) was used, and for the sediment samples synthetic water, representing surface water, such as in rivers/streams, was used (SM, Table S 4). In Thuringia, the water salinity varies greatly, so medium-hard synthetic water was prepared and used for sediment samples. As recommended by Smith et al. (2002), for CaCO3 containing solutions, CO2 gas was bubbled through for ca. 1 h until the poorly soluble CaCO3 precipitate was dissolved. All samples, reference soils, and blanks were extracted in duplicate due to the many samples. Soil 2 from each study site (Friemar and Großenstein) was extracted in quadruplicate to get information about the uncertainty of each experiment. The limits of our laboratory simulations are described in SM S 2.

2.4.1 Simulation of Total P Re-dissolution Following Erosion Caused by Two Heavy Rain Events

The heavy rain event simulation was designed to determine the total water-extractable content of P, simulating the situation following erosion and transport processes from soil to receiving water caused by heavy rain events. A heavy rain event was defined as ≥ 50 mm day-1 based on precipitation data from TLLLR weather stations (SM, Fig. S 1a + b). At both study sites, two heavy rain events were recorded in the months with special risk for erosion (May‒October), in Großenstein from 2005 to 2019 and in Friemar from 1994 to 2019. One event at each study site had intensities between 50 and 60 mm day-1 (2010: Friemar, 2007: Großenstein) and the other between 70 and 80 mm day-1 (2017: Friemar, 2019: Großenstein). To ensure comparability of both study sites, and to simulate extreme events in terms of increasing number and intensity of heavy rain events in future induced by climate change, an extreme value of two heavy rain events per year was chosen for the upscaling process of this simulation. Applied to sediments, it shows the total P re-dissolution from disturbed sediment into water. The experimental set-up is modified from the S 4-method (DIN 38, 414–4:1984–10). The suggested ratio of extract solution and soil (10:1) and extraction time (24 h) described in the S 4-method were used throughout. 4 ± 0.04 g of each sample was weighed into 50 mL centrifuge tubes and 40 ± 0.12 mL deionised/synthetic water was added to each sample. The suspensions were shaken in an overhead shaker ELU (Edmund Bühler GmbH) at 31 rpm for 24 h. Following extraction, the suspensions were centrifuged (4,000 rpm, 10 min; Centrifuge 5810, Eppendorf AG, Germany) and the supernatant decanted into new 50 mL centrifuge tubes. Approximately 37.5 mL was transferred to the new centrifuge tube and 2.5 mL remained, so 375 µL saturated MgSO4 solution (490 g L-1) was added to the supernatant to cause aggregation of particles, e.g. suspended matter. The supernatant was centrifuged again, filled into 13 mL tubes, and measured using ICP-OES and FIA. Additionally, organic carbon (Corg.) (centrifuged) was measured in all samples (multi N/C 2100, Analytik Jena AG, Germany; (DIN EN 1484:2019–04)). The extraction process was repeated three more times as sequential extraction. In addition, a similar laboratory simulation within 24 h was performed using Soil 2 (Großenstein) to determine the dissolution velocity of P, Al, Ca, Fe, and Mn as described previously, with the only difference being that 14 separate 50 mL centrifuge tubes were used and two tubes were sampled at every sampling timepoint. Samples were taken every 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h.

2.4.2 Simulation of P Re-dissolution via Diffusion Following Erosion

The P re-dissolution simulation investigated the P re-dissolution process from sediment via diffusion. The experimental set-up was designed to investigate P re-dissolution in lentic areas of waterbodies such as stagnant water areas (SM, Fig. S 2). The P re-dissolution from sediment under fluvial conditions such as in a river was also investigated (SM, Fig. S 3). 80 ± 0.8 g of each sample was placed into 1 L glass beakers, moistened with 30–40 mL deionised/synthetic water and a 90 mm glass fibre round filter (LABSOLUTE, particle retention 1.60 µm) was placed on top. A quartz sand–filled tube and three 1 cm diameter polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) balls were used to fix the filter in place. After that, 800 mL deionised/synthetic water was slowly filled into each beaker which was then covered with watch-glasses. A sample of 15 mL each was taken after 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10–11, 14–15, 21, and 28 days. One replica from samples Soil 1 and Soil 2 (Friemar) was continued over a period of 49 days. In addition to the main experiment, the diffusion speed of Ca3(PO4)2 was investigated by adding 0.45–0.46 g Ca3(PO4)2, based on the Ca concentration of the optimal fertilisation (Soil 2, Friemar), under 1 to 2 cm layer of quartz sand (131–136 g). The sampled volume was replaced with fresh extraction solution after each sampling and a correction was applied to account for this. The unmoved set-up, designed to simulate stagnant water bodies, was carried out in a dark cabinet to reduce biological activity. The moved set-up, designed to simulate flowing water bodies, was placed on a shaking machine SM 30 CONTROL (Edmund Bühler GmbH, 31 rpm). The centrifuged extracts (4,000 rpm, 10 min) were measured using ICP-OES and FIA. In addition, the redox potential (senTix® ORP900), oxygen concentration (FDO® 925), and conductivity (TetraCon® 325) were measured using electrodes (all: WTW GmbH, Germany).

2.4.3 Simulation of P Re-dissolution from Interstitial Sites

The percolation simulation shows the P leaching process of rain with respect to the flow of rain through the soil interstitial sites. This simulation was also applied to sediment samples, where it simulates the flow of surface water through the interstitial sites of a streambed or river sediment. Disturbed topsoils and sediments were used for this simulation, which indeed does not describe the original pore system but ensures direct comparability to the previous simulations to evaluate the P input due to re-dissolution from interstitial sites. The experimental set-up (SM, Fig. S 4) was as follows: A 25 mm glass fibre filter (1.0 µm particle retention rate, GE Water & Process Technologies; e.g. available at Fisher Scientific GmbH (2021)) was put into a 50 mL syringe and a small ceramic sieve with fine holes was placed on top of the filter for a constant flow. 65 \(\pm\) 0.65 g of each sample was added and then filled up to 1.5 cm from the top with quartz sand (1–2 cm layer) to avoid dead-volume. Another 25 mm glass fibre filter was added and the top of the syringe was closed with a plunger and silicon plug, both with a hole in the centre. Each plug was fixed using two cable ties. A tube connected the syringe to the volumetric flask for sampling and de-ionised/synthetic river water was pumped from the bottom to the top of the syringe. The main experiment (SM, Fig. S 5) was run for 28 days using two peristaltic pumps (type: 205U and 302SL, Watson-Marlow GmbH, 2.5 rpm). One replicate of Soils 1 and 2 from both study sites was continued over a period of 153 days. The percolation volume flow rate was calculated (SM, Eq. S 1) using the soil hydraulic conductivity data (10–40 cm day-1) for a comparable soil type (Eckelmann et al. 2005). Therefore, the percolation simulation was carried out using volume flow rates from 66 to 118 mL day-1. For the first 14 days, a sample was taken daily from 500 mL measuring flasks and the percolated volume noted. From day 15, a sample was taken every 2 days. The extracts were measured using the ICP-OES and FIA. In addition, dissolved Corg. (< 1.0 µm) and pH of the extracts from the first week were measured.

2.5 Upscaling to a Realistic Scenario

Upscaling from the laboratory simulations to a realistic scenario illustrates the P input processes from soil/sediment into receiving waters mainly via erosion (SM, Fig. S 6). It predicts a realistic scenario and shows the order of magnitude of the P input processes. Each experiment mimics a specific scenario which is possible in nature. The total Pload per year from soils/sediments (kg P (ha a)-1) into receiving waters at each site was calculated based on extracted P concentrations from each experiment. The Pshift, simulating water percolation through the soil interstitial sites, was extrapolated to real leaching of P into deeper regions of the soil beneath the scaling up the experimental conditions to reality using lysimeter data from TLLLR. Oehl et al. (2002) observed that 5‒11 kg P ha-1 a-1 were shifted from topsoils (0‒20 cm) to deeper subsurface layers (30‒50 cm), highlighting the need to consider shifted P. Khan et al. (2021) came to the same conclusion: available P-pools are translocated and accumulated to deeper layers in the soil profile. In addition, the resulting P concentrations (mg L-1) in the nearby surface water (river/stream) caused by soil erosion were calculated and compared to real water P concentrations measured by Thüringer Landesanstalt für Umwelt und Geologie (TLUG) (2014) to determine if the calculated P concentrations were within the real existing range. If the real values are much higher, this may be due to other point sources such as sewage waste and the P input through atmospheric deposition. They were further compared to the LAWA orientation values for total P (≤ 0.10 mg L-1) (Bund/Länderarbeitsgemeinschaft Wasser (LAWA) 2015) to judge environmental impact and evaluate eutrophication risk. The calculations used are listed in SM, Eq. S 2a–S 4c and all values reported in SM, Table S 5‒6.

3 Results

3.1 Soil Analysis/Characteristics

The pseudo total P content (P-pool) showed ca. 10–25% lower P values than the total P content (Table 1‒Table 2). For all samples, the range of plant available P (CAL) was between 37 and 117 mg kg-1 with a significantly higher value in the fertilised soils compared to the unfertilised soils. The pH values of all samples were in the range of 5.6–7.3. In the acidic pH range, it is thought that many more ions, particularly from metals such as Fe, Mn, and Al, were dissolved in aqueous solution and stopped P from being leached. 6–14% of the P-pool was plant available.

3.2 Laboratory Simulations

3.2.1 Simulation of Total P Re-dissolution Following Erosion Caused by Two Heavy Rain Events

The results from the Großenstein samples are further discussed as a representative example (Fig. 2b). The more fertiliser that is added to the field, the sharper the decrease in extracted P over time (24, 48, 72, and 96 h). The optimum fertilisation (Soil 2) results in the highest P concentration in the first extraction (24 h fraction). After that, the concentration reduces in each extraction. In the samples from test fields (Soil 1, Soil 2, and Soil 4) and “Hillside”, no difference between total P and inorganic PO43- as P was detected. Stutter et al. (2015) also found that P species were dominated by PO43- in 32 arable soils from the UK. In contrast, samples “Sediment” and particularly “Riparian strip” showed a 43% higher concentration in the 24 h fraction of total P than inorganic PO43− as P. Most of the organic P, defined as total P minus inorganic PO43- as P, is leached in the first extraction. After that, the extracted P is mostly present as inorganic PO43-. The Corg. (centrifuged) concentrations of the 24 h fractions were much higher (Fig. 3b) than the later fractions (e.g. “Riparian strip” (Großenstein), 24 h: 311 mg kg-1; 48 h: 90 mg kg-1). High concentrations of Ca (85–727 (median: 200 mg kg-1)) were extracted within 24 h and Fe, Mn, and/or Al concentrations were particularly high in the more acidic samples (“Riparian Strip” and “Sediment” from Großenstein) (SM, Fig. S 7–11). A range of 0.5–1.6% of the P-pool was extracted from soil samples from Friemar and Großenstein in one simulated heavy rain event (the first extraction). The extraction of P from sediments was lower than from the soils in both study sites (0.1–0.2% of P-pool).

Total P concentrations from study sites Friemar (a) and Großenstein (b) samples analysed via ICP-OES and PO43- as P concentrations analysed via FIA of the heavy rain event simulation using deionised water for all soil samples and synthetic water for the sediment sample as extraction agent. The error bars show the expanded uncertainties (\({k}_{95}\) = expansion factor = 2). Created using Python 3, JupyterLab 2.2.6

Corg. (centrifuged) concentrations analysed via multi N/C 2100 Analytik Jena AG, Germany from study sites Friemar (a) and Großenstein (b) of the heavy rain event simulation using deionised water for all soil samples and synthetic water for the sediment sample as extraction agent. The error bars show the expanded uncertainties (\({\mathbf{k}}_{95}\) = expansion factor = 2). Created using Python 3, JupyterLab 2.2.6

To get an idea how many heavy rain events of a similar magnitude and duration would have to follow to leach out the P concentration < LOQ, assuming that no more P is added or withdrawn, the graphs shown (Fig. 2) were linearly extrapolated (SM, Table S 7). Samples with lower extracted P concentrations such as “Hillside” from Friemar need more heavy rain events (20), compared to higher extracted P concentrations such as “Hillside” from Großenstein (9 heavy rain events), to reach a P concentration which is < LOQ because of the flatter slope of linear function. Due to the inaccuracy of such a linear extrapolation, all values given are a predicted minimum number of heavy rain events which is expected to be higher in reality due to a shallowing of the curve over time. Without outliers, a range of 7–12 (median: 9) minimum heavy rain events from all samples was achieved.

3.2.2 Simulation of P Re-dissolution via Diffusion Following Erosion

The results for the Großenstein samples are shown in Fig. 4. The fertilised samples from the test fields and sample “Hillside” showed a comparable P re-dissolution behaviour. As in the heavy rain event simulation, the optimum fertilisation (Soil 2) and “Hillside” re-dissolved the highest quantity of P. A maximum P value was reached after 10–21 days depending on experimental set-up (moved or unmoved). The P leaching behaviour commonly resembled a Gaussian bell curve. In samples from test site Friemar, no bell curve or even a plateau was reached after 28 days, but P concentrations continually increased (Fig. 5). For two metals, a polynomic relationship, similar to P (R2 = 0.86), was found over time (Ca: R2 = 0.99 and Mn: R2 = 0.62). For Al and Fe, no such similarity to P was found. To investigate the relationship between P and counter ions, a graphical stoichiometric correlation analysis for common phosphate salts associated with Al, Ca, Fe (Blume et al. 2016), and Mn (Boyle and Lindsay 1986) was carried out (SM, Fig. S 12a–b and Fig. S 13). The correlation analysis of Ca vs. P showed that when the P re-dissolution process reached a maximum, the Ca re-dissolution rate also decreased. In further support, the polynomic relationship between Ca and P could indicate that after the maximum, the precipitation process as, for example hydroxyapatite, is faster than the re-dissolution process of P and Ca from soil or sediment. This was also seen in Fe and Mn as when they finally dissolved, a high initial concentration was followed by a decrease in both the concentration of the counter ions and P. The range of P extracted from the P-pool was < 0.1–2.3% for all soil samples at Friemar and Großenstein in both set-ups. Temperature remained constant throughout the experiment (22.8–24.0 °C).

Total P concentrations analysed via ICP-OES and PO43- as P concentrations analysed via FIA from study site Großenstein of the P re-dissolution simulation for samples Soil 1 (no fertilisation) (a), Soil 2 (optimum fertilisation) (b), Soil 4 (-30% of optimum) (c), “Hillside” (d), “Riparian strip” (e) and “Sediment” (f). The error bars show the expanded uncertainties (\({\mathbf{k}}_{95}\) = expansion factor = 2). Created using Python 3, JupyterLab 2.2.6

Total P concentrations analysed via ICP-OES and PO43- as P concentrations analysed via FIA from study site Friemar of the P re-dissolution simulation for samples Soil 1 (no fertilisation) (a), Soil 2 (optimum fertilisation) (b), Soil 4 (-30% of optimum) (c), “Hillside” (d), “Riparian strip” (e) and “Sediment” (f). The error bars show the expanded uncertainties (\({k}_{95}\) = expansion factor = 2). Results for days 35, 42 and 49 are only achieved for Soil 1 and 2. The uncertainty from days 35, 42 and 49 are only 2 u (instrument) as there were no repeat determinations. In sample “Sediment” (unmoved) only one replicate was used due to a broken filter. Created using Python 3, JupyterLab 2.2.6

For study site Großenstein, from day 10 or 14, the extracted P values in the unmoved set-up were higher than in the moved set-up. This was particularly clear in sample “Riparian strip” (Großenstein). The redox potentials after finishing the experiment from the moved set-up were in a range from 144 to 220 mV, and from the unmoved set-up only from 55 to 169 mV. The oxygen concentrations of the moved set-up were constant and higher (7.7–8.0 mg L-1) than the unmoved set-up (3.6–5.7 mg L-1). The content of P extracted from soil from Friemar was 56‒85% higher than Großenstein in the moved set-up and 16‒26% lower in the unmoved set-up. The investigation into the diffusion speed using Ca3(PO4)2 found that after 28 days the saturation point of the moved set-up (6,9 mg P (kg Ca3(PO4)2)-1) was almost reached. The diffusion speed of the unmoved set-up was slightly slower; after 28 days 5,6 mg P (kg Ca3(PO4)2)-1 was extracted (SM, Fig. S 14). Error due to P adsorption onto the filters used in the P re-dissolution simulation was shown to be negligible.

3.2.3 Simulation of P Re-dissolution from Interstitial Sites

The accumulated content of P leached is shown in Fig. 6. In Friemar, the P of the fertilised soils (Soil 2 and 4) was leached quite quickly at the beginning (steep slope) while the leaching process of the unfertilised soil (Soil 1) was much slower. As shown in the previous experiments, high levels of P (68–95 mg kg−1) were leached from samples Soil 2 and “Hillside” from Großenstein after 28 days of percolation, removing high percentages from the P-pool (10–14%). Measuring P (CAL) before and after percolation showed that after 28 days of percolation using deionised/synthetic water, a large percentage of the P (CAL) was extracted (Großenstein: 21.6–47.6% and Friemar: 7.7–39.9%). The percolation simulation had comparatively high extracted P percentages of P-pool, from 0.7 to 13.9% after 28 days.

The long-term extraction behaviour (Soil 1 and Soil 2, > 28 days) from Friemar and Großenstein differed. In Großenstein, a plateau was reached comparably quickly, while in Friemar the P extraction rate reduced but total P extracted still increased. Also, the total extracted P in the optimally fertilised soil after 153 days was much higher in Großenstein than in Friemar, whereas the unfertilised soil showed comparable results in Großenstein (Soil 1: 65 mg kg-1 and Soil 2: 153 mg kg-1) and Friemar (Soil 1: 69 mg kg-1 and Soil 2: 111 mg kg-1). The results of “Riparian strip” suggested a quicker P leaching from Friemar (after 28 days: 31 mg kg-1, pH: 7.1) than from Großenstein (after 28 days: 17 mg kg-1, pH: 5.7) samples. Comparing the samples “Sediment”, in Großenstein, low total accumulated P concentrations (after 28 days: 3.3 mg kg-1), a comparably low pH (5.6) and higher concentrations of Mn (ca. 2.0‒3.5 mg kg-1 day-1) were found. In Friemar, high total accumulated P concentrations (after 28 days: 60.1 mg kg-1), a neutral pH (7.3), and low Mn (ca. 0.7‒1.5 mg kg-1 day-1) concentrations were observed. Confirming the results of the heavy rain event simulation, the total P concentration was twice as high as the inorganic PO43- concentration on the first day (SM, Fig. S 15a–f and Fig. S 16a–f). The Corg. (< 1.0 µm) also showed that on the first day the Corg. concentration was twice as high as the second day (SM, Fig. S 17a‒b).

A precipitate formed in the tubes and volumetric flasks, most apparent in two samples from Großenstein and one from Friemar. This was dissolved in 10 M HCl, to gauge the potential P measurement error due to precipitation. From Friemar: Sample “Sediment”, 5.4 mg kg-1 P and comparably low Fe, Mn, Al, and Ca concentrations (\(\le\) 20 mg kg-1) were found (SM, Fig. S 18a–b). In the Großenstein samples, relatively high concentrations of P (24.4 mg kg-1) and Fe (129 mg kg-1) were found in sample “Riparian strip” and “Sediment” (P: 17.1 mg kg-1 and Fe: 359 mg kg-1) extractions (SM, Fig. S 19a–c). The pH (26 °C) of the first week’s extracts ranged between 6.7 and 8.6 and no relationship with the P concentrations measured were found.

3.3 Upscaling to a realistic scenario

It was found that the main P input into receiving waters is from percolation through the interstitial sites of sediments. The results shown in Fig. 7a (Pload, 0.05–2.19 kg ha-1 a-1) are in line with those of Fortune et al. (2005) who estimated annual cumulative total P losses in drainage waters from four UK field sites (0.03–5 kg P ha-1, 2001–2002).

Estimated results of Pshift/load applied to reality from all laboratory simulations (a). Estimated results of Pconc. in surface (SF)-water applied to reality from all laboratory simulations (b). The red line shows the LAWA orientation value (Bund/Länderarbeitsgemeinschaft Wasser (LAWA) 2015) of 0.10 mg total P L-1). All error bars show the expanded uncertainties (\({\mathbf{k}}_{95}\) = expansion factor = 2) except the error of the grey bar (P re-dissolution via diffusion from sediments) which denotes the 5th and 95th percentile values. Created using Python 3, JupyterLab 2.2.6

The P input into receiving waters was much higher for the samples from Großenstein, especially for the fertilised samples, Soil 2 (0.64 mg L-1) and Soil 4 (0.37 mg L-1) as well as for “Hillside” (0.85 mg L-1), than for Friemar (0.02 to 0.11 mg L-1; median: 0.07 mg L-1) (Fig. 7b). This is a similar magnitude to the P concentration measured by TLUG (2014) in surface waters close to the Friemar site (0.15–0.3 mg L-1). At Großenstein, the values from TLUG were in a range of 0.10–0.15 mg L-1; however, in our study, most of the results achieved were higher (0.03–0.85 mg L-1; median: 0.30 mg L-1). All estimated results from Großenstein (except sample “Sediment”) were higher than the LAWA orientation value for total P (0.10 mg L-1). In Friemar, only the optimal fertilised soil sample exceeded the LAWA value.

A final summary of the P input into receiving or surface water via the four pathways described is schematically shown in Fig. 8. The P re-dissolution due to two heavy rain events (17%), via diffusion (13%), and leaching from soil interstitial sites (12.5%) only played a minor role compared to the main source of P in receiving waters, which was leaching from sediment interstitial sites (57.5%) via percolation.

Schematic final summary of the P input into receiving or surface water via the four pathways shown and examined in this study. Percentages are based on the median values and represent the percentage contribution of each individual P input path into surface waters, assuming that the four input paths represent the entire P input. The range and median values were extrapolated from all samples at both study sites. Created using Microsoft Paint 3D and Microsoft Word

4 Discussion

The results of all laboratory simulations are the basis for the upscaled realistic scenarios and are discussed below. All findings suggest that fertilised soils have a higher content of readily available, easily leachable P compared to unfertilised soils, as indicated by the initial spike in extracted P. This was found in all three laboratory simulations and is especially clear in the percolation simulation. The difference between total P and inorganic PO43- concentration in the first extraction is attributed to organic P and confirmed by the measured Corg. which was three times higher in the first extraction than the following extractions. High concentrations of organic P in soils are often associated with high concentrations of organic C (Frossard et al. 2000; Guggenberger et al. 1996). It is known that in soil solutions of humus rich soils, 20–70% of total dissolved P can be present as organic P (Blume et al. 2016). It is also known that adding water to dried soil results in a spike in the concentration of organic carbon (Slessarev and Schimel 2020). While fertilisation and drying of soils influenced the P content, it was not the only factor.

The comparably higher extracted P in sample “Hillside” from Großenstein compared to the same sample from Friemar is attributed to a steeper slope of hill in Großenstein than in Friemar. In Großenstein, the hillside had a slope from top to bottom (297 to 266 m above sea level), which corresponded to ~ 10% slope (GeoBasis-DE/BKG (Google) 2008). In Friemar, no significant slope (280 m above sea level, slope < 5 m) was observed (GeoBasis-DE/BKG (Google) 2008). A steeper slope could mean that P containing topsoils are shifted from the top of the hill to the flatter regions where it accumulates. In addition, the relatively sand-rich, clay-poor soil of the Großenstein “Hillside” sample means that P is more easily transported from this coarse-grained soil than the fine-grained soils found in Friemar and the rest of Großenstein (Auerswald and Weigand 1999). Furthermore, the adsorption rate for P onto clay particles is much higher than onto sand particles (Cao et al. 2013). This explains the study site-dependent P leaching behaviour over time, which showed that after 153 days almost no P could be extracted from the sand-rich, clay-poor samples from Großenstein, whereas P was still being removed from the clay-rich, sand-poor Friemar samples. A similar leaching behaviour was found by Lookman et al. (1995) for sandy Belgian and German soils over a time period of more than 1600 h.

Length of P extraction played a crucial role as high levels of P were found within the first 24 h of a heavy rain event simulation whereas, after 4 h, the P concentration within the extraction solution decreased, which is attributed to P precipitation with, e.g. metals and/or the readsorption onto clay particles (SM, Fig. S 20). As high concentrations of Ca were extracted, it is thought that high percentages of inorganic P were present as Ca-P compounds such as lime. This is in line with the findings from Cheng et al. (2019) investigating topsoils (0‒10 cm) in northwest China, who found that ca. 86% of total inorganic P is present as Ca-P. Most common Ca-P-based minerals are apatite (Ca5(PO4)3X (X = F, Cl, or OH)) and phosphorite (Ca5(PO4)3(OH, 0.5 CO3)) (Blume et al. 2016). Mn-P, Fe–P and Al-P compounds are also thought to be present, particularly in the acidic samples such as “Riparian Strip” and “Sediment” from Großenstein (Blume et al. 2016). Common examples are, for Mn-P: Lithiophilite (LiMnPO4) (Britannica 2021), for Fe–P: Vivianite (Fe3(PO4)2) ∙ 8 H2O, and for Al-P: Variscite (AlPO4 ∙ 2 H2O) (Blume et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2018). Readily available P is quickly leached from soil and then transferred into poorly soluble soil phosphates which are protected against leaching processes (Holsten et al. 2016; Pathak and Fagodiya 2022). Mineral P fertilisers such as superphosphates are highly soluble P sources which become plant available when water is present and leads to a distribution of soluble phosphates so that plants can access this readily available P. However, some of these phosphates directly react, for example with Ca, Mn, Fe, and/or Al ions to form poorly soluble compounds which might not be plant available. Anion exchange reactions or adsoption processes such as in/on clay particles are also possible. The counter ions from metals Al, Ca, Fe, and Mn led to an active retention of P and prevented it being leached by water; this was particularly clear when comparing the sediments from both study sites. When the pH was low enough to dissolve Fe and Mn, these dissolved ions immediately formed a new salt with P, so P migration was limited. If the counter ions were not present or were present in low concentrations, such as in sample “Sediment” from Friemar, much more P was dissolved. This means that high clay content and low pH reduced P leaching processes, reducing its transport to surface waters, and the eutrophication potential.

Conversely, a change from aerobic to anaerobic conditions in sediments increased the P extraction. Low redox potentials (below 100 mV or even negative based on the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE)) characterise oxygen-poor waters and high redox potentials (above 300‒500 mV, SHE) characterise oxygen-rich waters (Søndergaard 2009). The redox potential provides information about the form of P counter ions such as Fe2+/3+ and Mn2+/3+ present. Measurement of the redox potential (P re-dissolution simulation) and pH, which was assumed to be comparable to the measurements from the heavy rain and percolation simulation, allowed assessment of the predominant species present in the system by use of Pourbaix diagrams (Channei et al. 2017). This was investigated for Fe2+/3+ and Mn2+/3+ and found that Mn2+ is the predominant species under the experimental conditions, but iron was in the transition zone between Fe2+ and Fe3+. If the redox potential is low enough (above ~ 200 mV) that Fe3+ is reduced to Fe2+, then high concentrations of adsorbed or bonded P can be released (Søndergaard 2009). This could explain the higher P concentrations measured in the unmoved set-up from Großenstein. A missing oxic layer in the surface sediment and water phase allows the transformation from Fe3+ to the highly water-soluble form of Fe2+, so adsorbed or bonded P can be dissolved (Echterhoff and Meißner 2015; Mortimer 1971). In addition, it is known that obligate anaerobic microorganisms can dissolve iron oxides under reducing conditions, so phosphates adsorbed onto iron oxides are released (Blume et al. 2016). Furthermore, when there is a lack of oxygen, certain microorganisms (phosphorous-accumulating organisms (PAO)) degrade their polyphosphate pool and release orthophosphates to the environment in order to gain energy (Cydzik-Kwiatkowska and Nosek 2020). However, as stream water is highly unlikely to be anaerobic, this effect is considered negligible in such systems.

For simplicity, we analysed re-moistened soils at a constant temperature and did not account for the effect of influential factors such as temperature, season, soil water content, and bioactivity. P re-dissolution was up to 44% slower at low temperatures than at higher temperatures (SM, Table S 8 and Fig. S 21). This means that a temperature rise would increase the P re-dissolution such as P leaching from soil or P re-dissolution from sediment. Temperature is strongly related to season, soil water content, and bioactivity. Fabre et al. (1996) investigated the temporal distribution of P forms in the soil of a temporarily flooded riparian forest in France and found that organic and inorganic P (NaHCO3 and NaOH extracted) increased during winter and decreased significantly during spring by a factor of 2‒3. This finding was mainly attributed to mineralisation, plant uptake during the growing season, and erosional processes. They also concluded that increasing concentrations of labile P forms during late spring or summer can be attributed to the warm temperature and soil dryness which limited plant growth. Soil water content also strongly influences the P re-dissolution and the P plant uptake as water is the main transport P medium in soils. Bioactivity is increased during the warm season which means more P uptake and/or metabolism so bioactivity would lower the P content. However, if soils become too dry during warm weather, bioactivity would decrease, meaning that the P concentration would increase. The influence of environmental factors which we did not account for would pose an interesting avenue for future research. An important consideration is that drying and sieving of samples increases the soil pH (Penn and Bryant 2006). This should be considered if the pH values are to be interpreted in more detail. Drying led to further problems in the percolation simulation where the wetting process of all dried and sieved samples needed a long time (up to 14 days) leaving large air spaces, causing a heterogenous sample set before being completely wetted (further limitations see SM S 2). Due to errors introduced through drying and sieving, it is suggested that future studies use an undisturbed soil column.

All P-values upscaled to a realistic scenario are based on input via erosion (except the Pshift in soils (percolation simulation) which is based on leaching) which is the main P source into receiving waters (Tetzlaff et al. 2017). Diffuse sources of P such as run-off, interflow, drainage, groundwater, and deposition were not considered in this study. The main reason for the higher P input into receiving waters in Großenstein was due to the greater introduction of topsoils caused by the higher sediment delivery ratio (SDR) (20.2 vs. 17.9%) and average erosion potential (5.62 vs. 2.41 t ha-1 a-1) which was twice as high as in Friemar. Comparing both sampling sites, Großenstein (except sample “Sediment”) has a higher risk of eutrophication than Friemar.

The estimated results from the P re-dissolution simulation are only shown for the moved set-up because it is assumed that over 90% of stream water is flowing and only a negligible part of the river is stagnant. P re-dissolution is assumed to happen throughout the year although this is not known because the experiment only ran for 28 days. However, only very low P concentrations were extrapolated from both study sites, which probably plays an almost negligible role in streams. Concentrations of P in sediments were lower the limit of quantification which means that the P re-dissolution process via diffusion from sediments is negligibly small. In streams, fresh water flows above the sediment, replacing the water above the sediment layer. In the moved set-up, the water phase was moved but not replaced which might have led to different results, especially close to the end of experiment where the dissolved P concentrations were higher and therefore the diffusion potential decreased.

The estimated results from the percolation simulation, which ran only 28 days, were linearly extrapolated to 365 days per year. The P extraction in the further course of experiment (> 28 days) showed that P extraction does not increase linearly over a full year, but the curve flattens. That means that the results may have been overestimated from the percolation simulation. Furthermore, only the humus-rich topsoils (0–25 cm) were analysed but extrapolated to much deeper regions in soil depending on study site (90–230 cm). The calculation did not account for any P lost between the topsoil analysed and the groundwater. Finally, the lysimeter data used to scale up the measured results were taken from a different soil so may not accurately reflect the samples measured from Friemar and Großenstein.

Due to climate change, heavy rain events are expected with greater frequency and intensity; with this dataset, it is possible to adjust the calculations and estimate the effect of more than two heavy rain events on P-input. The estimated annual input due to heavy rain events is lower than the results from the percolation simulation, despite the extreme scenario of two heavy rain events which was selected for the upscaling simulation. However, it is expected that future changes in heavy rain frequency and intensities may result in greater P input into receiving waters.

The evaluation of effectiveness of riparian strips strongly depends on its cultivation, width, and slope. Both riparian strips were cultivated with grass; the riparian strip in Großenstein (width ~ 10 m, ca. 10% slope) was much wider than in Friemar (width ~ 5 m, flat). The riparian strip from Großenstein was effective at capturing P; Pload from the Großenstein riparian strip was almost ten times greater than in the sediment. Friemar had a neutral pH and therefore fewer counter ions, allowing greater P leaching, especially via percolation through interstitial sites. However, even if the riparian strip at Friemar works less effectively than at Großenstein, it still prevents excessive erosion processes and is a ca. 5 m space where no fertilisers are applied. It was shown that much higher P concentrations were released from the fertilised soils in both study sites than from the unfertilised soils. As shown, this does not necessarily mean that this P reaches the receiving water. In summary, it is important to keep a riparian strip between fertilised fields and nearby surface waters to reduce P input into receiving waters. This can be improved by cultivating the riparian strip so the shifted P is taken up by plants and therefore removed during harvest (Djodjic and Markensten 2019). Almeida et al. (2019) found in a 2-year Brazilian field experiment that crops such as ruzigrass decrease P mobility by reducing P diffusion and resupply from the soil solid phase, which highlights the importance of cultivation. In addition, long-term planting increases aggregate stability, particularly in topsoils, which then reduces soil erosion (Khan et al. 2022). Lastly, during this study, only the short-term effects of the riparian strip could be evaluated but not the long-term effects which could be determined doing a long-term fieldwork-based analysis.

5 Conclusion

We investigated the phosphorus (P) input and re-dissolution processes into receiving waters from topsoils and sediments using three laboratory simulations. The outcome after upscaling the results of simulations to a realistic scenario indicated that the total P re-dissolution caused by two heavy rain events and the P re-dissolution via diffusion, both following erosion, only play a minor role in the P input processes into receiving waters compared to the P re-dissolution from interstitial sites, particularly the sediment interstitial sites, also following erosion. The results indicated that the P re-dissolution, and consequently the P input processes via erosion into receiving waters, was much higher from sandy compared to clayey soils. However, the P re-dissolution potential for the stream sediments of both, the sandy and clayey study site, was below threshold indicating a risk of eutrophication. Rather, local differences such as a steeper slope, different soil compositions, and poorer buffering due to lower lime and Al content compared to the clay-rich soils at Friemar were the decisive reasons. We showed that significantly more P re-dissolution and leaching occurred from the fertilised than unfertilised soils regardless of whether they were clayey or sandy soils. In addition, the first extraction after drying and sieving had a large contribution from organic P. Furthermore, we found, particularly in sediments, that the P re-dissolution rate was strongly related to the O2 concentration, redox potential, temperature, pH, and associated dissolved P counter ions. The P re-dissolution rate was lower, the higher the concentration of dissolved P counter ions such as Ca2+, Fe2+ and Mn2+. The high effectiveness of the riparian strip in Großenstein was due to ~ 10% slope, ~ 10 m width and a high P retention potential due to low pH. Contrastingly, the riparian strip in Friemar had no slope, ~ 5 m width and a low P retention potential due to neutral pH making it comparably weak. In conclusion, the main P input process into receiving waters following erosion is the P re-dissolution from sediment interstitial sites which was significantly reduced having an appropriate riparian strip with sufficient slope, width and buffering capacity.

Data Availability

The datasets used can be found in the supplementary material or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Almeida DS, Menezes-Blackburn D, Zhang H, Haygarth PM, Rosolem CA (2019) Phosphorus availability and dynamics in soil affected by long-term ruzigrass cover crop. Geoderma 337:434–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.09.056

Auerswald K, Weigand S (1999) Kapitel 3 - Eintrag und Freisetzung von P durch Erosionsmaterial in Oberflächengewässern. VDLUFA 50(1999):37–54 (in German)

Blume H-P, Brümmer GW, Fleige H, Horn R, Kandeler E, Kögel-Knabner I, Kretzschmar R, Stahr K, Wilke B-M (2016) Inorganic soil components — minerals and rocks; soil-plant relations. In: Scheffer/Schachtschabel (ed) Soil science, 1st edn. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, pp 30, 444–454

Boyle FW, Lindsay WL (1986) Manganese phosphate equilibrium relationships in soils. Soil Sci Soc Am J 50:588–593. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1986.03615995005000030009x

Britannica (2021) Lithiophilite. In: Gaur et al (ed) Encyclopaedia britannica. Available via: https://www.britannica.com/science/lithiophilite. Accessed 13 Dec 2021

Bund/Länderarbeitsgemeinschaft Wasser (LAWA) (2015) LAWA-AO - Rahmenkonzeption Monitoring - Teil B Bewertungsgrundlagen und Methodenbeschreibungen - Arbeitspapier II Hintergrund- und Orientierungswerte für physikalisch- chemische Qualitätskomponenten zur unterstützenden Bewertung von Wasserkörpern. In: Bund/Länderarbeitsgemeinschaft Wasser Ausschuss “Oberirdische Gewässer und Küstengewässer.” Available via: https://www.gewaesser-bewertung.de/files/rakon_b_-_arbeitspapier-ii_stand_09012015.pdf. Accessed 22 Mar 2021 (in German)

Cao Y, Huang Q, Cai P (2013) Adsorption of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) from pseudomonas putida on various soil particles from an alfisol. In: Xu J, Wu J, He Y (eds) Functions of natural organic matter in changing environment. Springer, Dordrecht, p 173

Channei D, Phanichphant S, Nakaruk A, Mofarah SS, Koshy P, Sorrell CC (2017) Aqueous and surface chemistries of photocatalytic Fe-doped CeO2 nanoparticles. Catalysts 7:1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7020045

Cheng Z, Chen Y, Gale WJ, Zhang F (2019) Inorganic phosphorus distribution in soil aggregates under different cropping patterns in northwest China. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 19:157–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-019-00022-1

Cydzik-Kwiatkowska A, Nosek D (2020) Biological release of phosphorus is more efficient from activated than from aerobic granular sludge. Sci Rep 10:1–2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67896-5

Dannemann G (2015) Federal Water Act (Wasserhaushaltsgesetz (WHG) §38a). Available via: https://germanlawarchive.iuscomp.org/?p=326. Accessed 14 Mar 2022

DIN 38414–4:1984–10 (1984) Determination of leachability by water (S 4). In: Wasserchemische Gesellschaft in der GDCh (ed) German standard methods for the examination of water, waste water and sludge; sludge and sediments. Beuth, Berlin, pp 1–12

DIN EN 1484:2019–04 (2019) Water analysis - Guidelines for the determination of total organic carbon (TOC) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) (H 3). In: Wasserchemische Gesellschaft in der GDCh (ed) German standard methods for the examination of water, waste water and sludge; sludge and sediments. Beuth, Berlin, pp 1–20

DIN ISO 11277:2020-04 (2020) Soil quality - determination of particle size distribution in mineral soil material - method by sieving and sedimentation. Beuth, Berlin, pp 1–38

Djodjic F, Markensten H (2019) From single fields to river basins: identification of critical source areas for erosion and phosphorus losses at high resolution. Ambio 48:1129–1142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1134-8

Echterhoff J, Meißner J (2015) Die gewässerchemischen und chemisch-physikalischen Prozesse einer Trinkwassertalsperre unter Berücksichtigung eines dynamisierten Talsperrenbetriebs. Enerwa 02:1–66 (in German)

Eckelmann W, Finnern H, Grottenthaler W, Kühn D (2005) Bodenkundliche Kartieranleitung. KA5. Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe in Zusammenarbeit mit den Staatlichen Geologischen Diensten, Hannover, (in German)

Fabre A, Pinay G, Ruffinoni C (1996) Seasonal changes in inorganic and organic phosphorus in the soil of a riparian forest. Biogeochemistry 35:419–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02183034

Fisher Scientific GmbH (2021) Whatman 1821–025, grade GF/B filter for liquid scintillation, 25 mm circle, perticle retention rate 1.0 µm. Available via: https://www.fishersci.de/shop/products/whatman-binder-free-glass-microfiber-filters-grade-gf-b/11300574. Accessed 26 Mar 2021

Fortune S, Lu J, Addiscott TM, Brookes PC (2005) Assessment of phosphorus leaching losses from arable land. Plant Soil 269:99–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-004-1659-4

Frossard E, Condron LM, Oberson A, Sinaj S, Fardeau JC (2000) Processes governing phosphorus availability in temperate soils. J Environ Qual 29:15–23. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2000.00472425002900010003x

Fürstenau C, Harzendorf D (2016) KUP am Fließgewässer – Streifenförmiger Anbau schnellwachsender Bäume entlang eines Fließgewässers zur Vermeidung von Stoffeinträgen. Thüringer Landesanstalt für Landwirtschaft (TLL) (in German)

GeoBasis-DE/BKG (Google) (2008) Google maps. Available via: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Germany. Accessed 9 Oct 2020

Glibert PM, Seitzinger S, Heil CA, Burkholder JM, Parrow MW, Codispoti LA, Kelly V (2005) The role of eutrophication in the global proliferation of harmful algal blooms. Oceanogr 18:198–209. https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2005.54

Guggenberger G, Christensen BT, Rubæk G, Zech W (1996) Land-use and fertilization effects on P forms in two European soils: resin extraction and 31P-NMR analysis. Eur J Soil Sci 47:605–614. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.1996.tb01859.x

Hellmann S, von Tümpling W, Bräutigam P (2020) Analytical investigations to estimate phosphorus re-dissolution rates in trace levels of selected topsoils and river sediments. Friedrich Schiller University Jena, unpublished

Holsten B, Pfannerstill M, Trepel M (2016) Phosphor in der Landschaft - Management eines begrenzt verfügbaren Nährstoffes. CAU Kiel, pp 1–52, (in German)

Holtan H, Kamp-Nielsen L, Stuanes AO (1988) Phosphorus in soil, water and sediment: an overview. Hydrobiologia 170:19–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00024896

Khan A, Jin X, Yang X, Guo S, Zhang S (2021) Phosphorus fractions affected by land use changes in soil profile on the loess soil. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 21:722–732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-020-00395-8

Khan FU, Khan AA, Li K, Xu X, Adnan M, Fahad S, Ahmad R, Khan MA, Nawaz T, Zaman F (2022) Influences of long-term crop cultivation and fertilizer management on soil aggregates stability and fertility in the loess plateau, northern China. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-021-00744-1

Killiches F, Gebauer H-P, Franke G, Röhling S, Schulz P (2013) Phosphat - Mineralischer Rohstoff und unverzichtbarer Nährstoff für die Ernährungssicherheit weltweit. Bundesanstalt für Geowissenshaften und Rohstoffe (BGR), (in German)

Lookman R, Freese D, Merckx R, Vlassak K, Van Riemsdijk WH (1995) Long-term kinetics of phosphate release from soil. Environ Sci Technol 29:1569–1575. https://doi.org/10.1021/es00006a020

Mortimer CH (1971) Chemical exchanges between sediments and water in the great lakes-speculations on probable regulatory mechanisms. Limnol Oceanogr 16:387–404. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1971.16.2.0387

Oehl F, Oberson A, Tagmann HU, Besson JM, Dubois D, Mäder P, Roth HR, Frossard E (2002) Phosphorus budget and phosphorus availability in soils under organic and conventional farming. Nutr Cycling Agroecosyst 62:25–35. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015195023724

Pathak H, Fagodiya RK (2022) Nutrient budget in Indian agriculture during 1970–2018: assessing inputs and outputs of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 1:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-022-00775-2

Penn C, Bryant RB (2006) Incubation of dried and sieved soils can induce calcium phosphate precipitation/adsorption. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 37:1437–1449. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103620600628904

Riddle M, Bergström L, Schmieder F, Kirchmann H, Condron L, Aronsson H (2018) Phosphorus leaching from an organic and a mineral arable soil in a rainfall simulation study. J Environ Qual 47:487–495. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2018.01.0037

Seppälä J, Knuuttila S, Silvo K (2004) Eutrophication of aquatic ecosystems a new method for calculating the potential contributions of nitrogen and phosphorus. Int J Life Cycle Assess 9:90–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02978568

Siegesmund A (2019) Neuregelungen zum Gewässerrandstreifen anhand der Novelle des Thüringer Wassergesetzes (ThürWG) 2019. Thüringer Ministerium für Umwelt, Energie und Naturschutz, Erfurt, (in German)

Slessarev EW, Schimel JP (2020) Partitioning sources of CO2 emission after soil wetting using high-resolution observations and minimal models. Soil Biol Biochem 143:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2020.107753

Smith EJ, Davison W, Hamilton-Taylor J (2002) Methods for preparing synthetic freshwaters. Water Res 36:1286–1296. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1354(01)00341-4

Søndergaard M (2009) Redox potential. In: Likens GE (ed): Encyclopedia of inland waters. Elsevier Inc., pp 852–859

Stürmer B, Waltner M (2021) Best available technology for P-recycling from sewage sludge — an overview of sewage sludge composting in Austria. Recycl 6:1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling6040082

Stutter MI, Shand CA, George TS, Blackwell MSA, Dixon L, Bol R, MacKay RL, Richardson AE, Condron LM, Haygarth PM (2015) Land use and soil factors affecting accumulation of phosphorus species in temperate soils. Geoderma 257–258:29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2015.03.020

Tetzlaff B, Kreins P, Kuhr P, Kunkel R, Wendland F (2017) Quantifizierung der Stickstoff- und Phosphoreinträge ins Grundwasser und die Oberflächengewässer Thüringens mit eintragspfadbezogener und regionaler Differenzierung Endbericht. In: Forschungszentrum Jülich Institut für Bio- und Geowissenschaften (IBG 3: Agrosphäre). Available via: https://gewaesserschutz-thueringen.de/wp-content/uploads/Endbericht_Thüringen12_8_2017.pdf. Accessed 7 Feb 2022 (in German)

The European parliament and the council of the European union (2000) Directive 2000/60/EC of the European parliament and of the council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for community action in the field of water policy: water framework directive (WFD). OJEC L327:1–72

Thüringer Landesanstalt für Umwelt und Geologie (TLUG) (2014) Monitoringbericht 2014 Ergebnisse der biologischen und chemischen Überwachung oberirdischer Gewässer. Available via: https://docplayer.org/11618711-Ergebnisse-der-biologischen-und-chemischen-ueberwachung-oberirdischer-gewaesser.html. Accessed 7 Feb 2022 (in German)

Wasserhaushaltsgesetz (WHG) §38a (2020) Bundesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2020 Teil I Nr. 30, ausgegeben zu Bonn am 29. Juni 2020 - Erstes Gesetz zur Änderung des Wasserhaushaltsgesetzes. (in German)

Zhang X, Liu X, Zhang M, Dahlgren RA, Eitzel M (2010) A review of vegetated buffers and a meta-analysis of their mitigation efficacy in reducing nonpoint source pollution. J Environ Qual 39:76–84. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2008.0496

Zhu J, Li M, Whelan M (2018) Phosphorus activators contribute to legacy phosphorus availability in agricultural soils: a review. Sci Total Environ 612:522–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.095

Zorn W (1998) Untersuchungen zur Charakterisierung der Phosphorverfügbarkeit in Thüringer Carbonatböden. Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, unpublished, (in German)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the TLLLR employees from department 2, “Referat 22”, for measuring the soil characteristics. We would also like to acknowledge the reviewers for their constructive comments.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This paper is based on the master’s thesis of Steffen Hellmann (Friedrich Schiller University Jena), supported financially and personally by the Thuringian State Office for Agriculture and Rural Areas – TLLLR, Jena, Germany. To avoid repetition, we state here that selected content was taken directly from the original work (Hellmann et al. 2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Steffen Hellmann: sampling, interpretation, visualisation, lab-work, measurements, data analysis, extrapolation to realistic scenario, writing the original draft. Günter Kießling: experimental design, instrumentation, supervision. Matthias Leiterer: creation of study, supervision. Marcus Schindewolf: sampling, extrapolation to realistic scenario, ArcGIS work. Alice Orme: interpretation, critical manuscript revision. Wolf von Tümpling: creation of study, experimental design, critical manuscript revision, supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hellmann, S., Kießling, G., Leiterer, M. et al. Analytical Investigations to Estimate Phosphorus Re-dissolution Rates in Trace Levels of Selected Topsoils and River Sediments. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 22, 3304–3321 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-022-00888-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-022-00888-8