Key Summary Points

The aim was to examine factors associated with different subtypes (stress, urgency and mixed) of urinary incontinence among older female hip fracture patients using a cross-sectional design.

AbstractSection FindingsUrinary incontinence was frequent, and the most common type was urgency incontinence. Stress incontinence and urgency incontinence were associated with different modifiable risk factors, all of which were associated also with mixed incontinence.

AbstractSection MessageDifferent risk factors converge in mixed urinary incontinence. Comprehensive geriatric assessment is key in the assessment of UI in older hip fracture patients.

Abstract

Purpose

Urinary incontinence (UI) is known to be common among older female hip fracture patients. Little is known about different subtypes of UI among these patients. Our aim was to identify factors associated with subtypes of UI in a cross-sectional design.

Methods

1,675 female patients aged ≥ 65 and treated for their first hip fracture in Seinäjoki Central Hospital, Finland, during 2007–2019, were included in a prospective cohort study. Of these, 1,106 underwent comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), including questions on continence, at our geriatric outpatient clinic 6 month post-fracture. A multivariable-adjusted multinomial logistic regression model was used to examine factors associated with UI subtypes.

Results

Of the 779 patients included, 360 (46%) were continent and 419 (54%) had UI 6-month post-fracture. Of the women with UI, 117 (28%) had stress UI, 183 (44%) had urgency UI and 119 (28%) had mixed UI, respectively. Mean age of the patients was 82 ± 6,91. In multivariable analysis, depressive mood and poor mobility and functional ability were independently associated with stress UI. Fecal incontinence (FI) and Body Mass Index (BMI) over 28 were independently associated with urgency UI. Mixed UI shared the aforementioned factors with stress and urgency UI and was independently associated with constipation.

Conclusions

Mixed UI was associated with most factors, of which depressive mood and impaired mobility and poor functional ability were shared with stress UI, and FI and higher BMI with urgency UI. CGA is key in assessing UI in older hip fracture patients, regardless of subtype.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI), defined as any reported involuntary loss of urine according to the International Continence Society [1], affects women disproportionately compared to men, and its prevalence increases with advancing age. Nearly 40% of women older than 60 years and 80% of women residing in long-term care have UI [2, 3]. UI is one of the most common geriatric syndromes and associated with adverse outcomes, such as decline in quality of life, disability, and depression. As opposed to UI as an urogynecologic condition in younger women, factors leading to the development of UI in older women are complex and often related to multifactorial health conditions and functional limitations. Despite high prevalence, UI remains under-reported and -managed. [2, 4, 5]

UI can be further classified into stress urinary incontinence (SUI), urgency urinary incontinence (UUI), and mixed urinary incontinence (MUI). SUI is defined as complaint of involuntary loss of urine on effort or physical exertion such as coughing or lifting, UUI as complaint of involuntary loss of urine associated with urgency, a sudden desire to void, and MUI as combination of the other two [1]. SUI is known to be the most prevalent subtype among women over-all reaching its peak in the fifth decade [6]. In Nurse’s Health study with over 10,000 participants affected by UI 56% of women aged between 41 and 83 years reported SUI, while 23% reported UUI and 21% MUI, respectively [7]. However, the prevalences of UUI and MUI exceed that of SUI in older age groups [6, 8]. There is evidence that MUI might have a greater physical and mental health burden compared to UUI or SUI in isolation [7, 9,10,11]. Of note, urgency with or without UI often combined with increased daytime urinary frequency and nocturia, is regarded as the key symptom of the overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome [12].

UI, and especially UUI, has been recognized as a risk factor for falls in older individuals [13, 14]. Hip fracture, one of the most devastating consequences of a fall, is a common and severe injury among older women with well-known consequences of increased mortality, morbidity, and health care costs [15, 16]. We have previously demonstrated over-all UI to be highly prevalent among older female hip fracture patients, and associated with older age, cognitive disorder, functional disability, depressive mood, and constipation [17]. Literature on associated factors of different UI-subtypes remains scarce, especially in this patient population. The treatment modalities available for UI depend on the subtype. However, since the relationship between the UI subtypes is complex, especially among older patients [6, 18], our aim was to examine factors associated with different subtypes of UI, and how they might differ between the groups in this vulnerable patient population.

Methods

Study population

This study was a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data. As described in our previous works [17, 19], the study population consisted of 1,675 older women suffering their first hip fracture between September 2007 and January 2019. Patients were aged ≥ 65 and managed in Seinäjoki Central Hospital, which is the only hospital providing acute surgical care in the Hospital District of Southern Ostrobothnia, with a catchment area of approximately 200,000 residents. Pathologic and periprosthetic fractures were excluded from the study. All the patients were invited to a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) at our out-patient clinic, which took place in a median time of 6 months (IQR 4–6 months) after the fracture. All participants or their representatives gave informed consent. The study design was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southern Ostrobothnia. The study complies with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

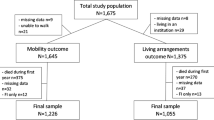

A total of 1,106 women attended the CGA. Data on continence status or subtype of UI was missing from 194 patients, leaving 912 women with the data on continence at 6 month post-fracture. After further exclusions of patients with missing data on covariates, a final sample of 779 women was generated for the statistical analyses of the associations of outpatient domains with the different UI subtypes. The study population is presented in detail in Fig. 1.

Study protocol and variables

The study protocol and the variables used in our study have been described in greater detail elsewhere [17, 20]. Briefly, a trained geriatric nurse interviewed the patients or their representatives during hospitalization and retrieved data from the medical records. The preoperative American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) risk scores were used to assess general health at the time of the fracture. There are five classes: (1) healthy person, (2) mild systemic disease, (3) severe systemic disease, (4) severe systemic disease that is a constant threat of life, and (5) a moribund person who is not expected to survive without surgery [21]. ASA scores were used as an indicator of comorbidity in our analysis.

At the outpatient clinic, CGA was performed by a multidisciplinary team consisting of a geriatric nurse, a physiotherapist and a geriatrician or a trainee in geriatric medicine. Both the patients and their next of kin or carer were invited to the clinic [20]. The geriatric nurse carried out the interview and the assessment of the domains with the selected tools. We used official Finnish translations of well-known and validated tools in the CGA. Cognitive function was measured with the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) [22], nutritional status was assessed using the Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA-SF) [23], depressive mood with the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) [24], and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) by Lawton and Brody [25]. Patient’s body mass index (BMI) was also measured during the assessment and the number of regularly taken medications elicited. The physiotherapist’s assessment of the patient’s physical performance included the Timed up and go-test (TUG) assessing mobility, balance, and risk of falls [26], the Elderly Mobility Scale (EMS) which represents patient’s mobility and ability to perform basic activities of daily living [27], and grip strength as a measure of muscle strength. Grip strength was measured in the stronger hand with a Jamar dynamometer and defined as weakened if less than 16 kg [28]. In cases of MNA-SF and TUG, variables were dichotomized for statistical purposes.

UI was defined as any reported involuntary loss of urine, and FI as any reported involuntary loss of faeces, as in our previous works [17, 19]. Questions based on different UI subtypes were used to determine the likely UI type the patient was affected by. SUI was defined as having urinary leakage during physical exertion such as lifting or coughing, UUI as having urinary leakage associated with urgency symptom i.e. a sudden urge to void, and MUI as a combination of the other two [29]. Data on self-reported constipation (yes or no) and new falls after fracture (yes or no) were also elicited. Considering a substantial proportion of respondents were old and/or cognitively impaired, simple survey-like questions were preferred to using structured questionnaires. The categorization of outpatient domains is presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Statistical analyses

Groupwise comparisons between the continent and different UI subtype groups were performed using the Pearson’s Chi2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Multivariable-adjusted multinomial logistic regression analysis, where all the variables were simultaneously included in the model, with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) was conducted to examine the associations of the outpatient domains with SUI, UUI and MUI at follow-up using the continent group as a reference. IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0 for Windows software (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois) was used for statistical analyses. All tests were two-sided and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the original study population of 1,675 women, 638 (38%) were continent at the time of the fracture, 874 (52%) had UI, and data on continence status was missing in 163 (10%) of the cases. Mortality rate before the CGA was 18% (307 women). Of the 779 surviving patients attending the outpatient CGA, 360 (46%) were continent and 419 (54%) had UI 6 month post-fracture. Of the women with UI 117 (28%) had SUI, 183 (44%) had UUI, and 119 (28%) had MUI, respectively. Mean age of the patients was 82 ± 6, 91. Distributions of outpatient domains between the continent and different UI subtype groups are presented in Table 1. The continent women tended to be slightly younger, have fewer medications, less disability and impaired mobility, less depressive mood, and lower BMI than women suffering from any type of UI. Especially those affected by MUI tended to be older, in poorer physical condition according to the EMS, having more medications, malnutrition and FI compared to the other groups (Table 1).

In the multivariable model, depressed mood (OR 3.53, 95% CI 1.99–6.23) according to GDS-15 and impaired mobility and functional ability (OR 2.74, 95% CI 1.48–5.09) according to EMS were independently associated with SUI at 6 month post-fracture. Self-reported FI (OR 2.60, 95% CI 1.22–5.54) and BMI over 28 (OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.15–2.81) were independently associated with UUI. Depressive mood (OR 2.11, 95% CI 1.15–3.87), impaired mobility and functional ability (OR 2.41, 95% CI 1.28–4.54), FI (OR 3.61, 95% CI 1.65–7.90), BMI over 28 (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.62–4.88) as well as self-reported constipation (OR 1.78, 95% CI 1.05–3.03) were all independently associated with MUI at 6 month post-fracture (Table 2).

Discussion

As we have already established in our previous work [17] overall UI is very common among older female hip fracture patients with over half of the patients being affected in this study. This study sheds light on the different subtypes of UI in this patient group. UUI was the most common UI-type followed by MUI and SUI. The prevalences of different UI subtypes have varied greatly in previous studies due to differences in definitions, study populations, reporting, and age distributions of the participants. In studies including also older women, prevalences of SUI, UUI, and MUI have ranged between 14–26%, 6–50% and 14–31%, respectively [30,31,32,33]. The prevalence of UUI in our study lands on the higher end of the range compared to previous literature, reflecting our considerably old and selected multimorbid patient population.

Interestingly, in this study there was little difference in prevalences between MUI and SUI, although MUI has been established to dominate in older age groups [6, 8]. This might be partly explained by selection and survivor bias. Given our old and vulnerable study population, patients in poorest of health were more likely to die or drop out before the outpatient CGA and less likely to answer the questions on UI subtypes during the CGA, resulting in lower-than-expected prevalence of MUI. However, we found no studies directly examining prevalences of different UI subtypes among hip fracture patients. Hip fracture is a major trauma likely affecting the pelvic floor, and it is followed by a period of immobilization and rehabilitation when loss of muscle mass, including the pelvic floor, and function is to be expected. Since our study had a cross-sectional setting, we cannot establish causality, and this calls for further studies focusing on changes in the subtypes of UI in this patient population.

Depressive mood was associated with both SUI and MUI and the association wasn’t far from being significant with UUI. The association between depression and over-all UI has been demonstrated before in older women living in the community [34], and after a hip fracture [17]. Moreover, depression is a recognized risk factor for hip fractures [35], and patients recovering from a hip fracture are at risk of developing depression [36], suggesting a bidirectional relationship between the two conditions. The patients attended the outpatient CGA during the recovery period of the fracture when moving and toileting are expected to be slower and more burdensome because of pain and imbalance, possibly precipitating incontinence, and further declining patient’s quality of life and thus, negatively affecting mental wellbeing. Why the association was strongest for SUI calls for further studies with longitudinal design.

Impaired mobility and functional ability according to EMS were associated with SUI and MUI. We have previously established a bidirectional relationship between over-all UI and mobility in our study population: pre-fracture impaired mobility predicts incident UI [19], and pre-fracture UI predicts decline in mobility 1 year post-fracture [37]. Both TUG score and grip strength failed to reach statistical significance in our analysis, possibly due to relatively large proportion of missing data. Interestingly, UUI was not associated with abnormal EMS score. In a previous study by Fritel et al., an opposite result was found where UUI and not SUI was associated with limitations of motor and balance skills [38]. In another recent study, better lower extremity physical function protected from incident UUI and MUI [39]. The lack of association might be partly explained by our selected study population. The hip fracture and following surgery have major impact on patient’s mobility and possibly pelvic floor, which may have different impact depending on UI subtype. This calls for further studies with bigger samples.

Our analysis included data on new falls after the fracture. Even though falls tended to be more common among patients reporting any type of UI compared to their continent counterparts, new falls after the fracture were not associated with any UI type 6 month post-fracture in the multivariable-adjusted analysis. In previous literature, UI and especially UUI has been associated with an increased risk of falls [13, 14]. However, the underlying cause for this connection has been under some debate. Previously suggested simple rationale such as rushing to the toilet caused by the sense of urgency has been questioned [13, 40], and the current evidence suggests that likely both UI and falls are markers of underlying vulnerability and disability [14, 41, 42]. Our results concur with these findings, given that our analysis was adjusted with considerable number of factors (many of which represent disability and vulnerability) and our selected study population consisted of participants with high level of disability as already demonstrated in our previous works [17, 19]. Both UI and falls likely represent the vulnerable state of these patients without causal relationship.

BMI over 28 was associated with UUI and MUI in our study, the association being stronger for MUI. Obesity has been found to be a significant risk factor for any UI subtype in older women [43, 44]. Komesu et al. found age between 80 and 90 and BMI over 35 to be a predictors of incident MUI, as well as lower remission rates during a 2 year follow-up [18]. In another study by Pang et al., women aged 60 or over and with BMI over 24 had a higher predicted probability of remaining with or progressing to MUI from either SUI or UUI during a 4 year follow-up [45]. Since obesity also exerts challenges to mobilizing and rehabilitating the patient after a hip fracture, and on the other hand these patients frequently suffer from malnutrition [46] and thereby might carry the risk of sarcopenic obesity [47], preventing or managing UI by weight loss presents a clinical challenge in these patients.

FI was associated with both UUI and MUI 6 month post-fracture, again the association being stronger for MUI. Constipation was also independently associated only with MUI, but this result should be interpreted with caution, given that data on constipation was missing in nearly every third patient with SUI and every fifth with UUI. We demonstrated the association of constipation with over-all UI in our previous work [17]. Constipation is a known risk factor for UI with multidimensional causes such as insufficient mobility and hydration, as well as comorbidities [48, 49], all which patients with hip fracture are susceptible to. Coyne et al. demonstrated a significant overlap of UUI, constipation and FI in general population of both men and women aged 40 and over [50]. The association with FI might also be related to overuse of laxatives to treat constipation, or incidents of overflow FI related to severe constipation [50]. In a study by Botlero et al., loose FI was a risk factor for any type of UI independent of age or BMI in community-dwelling women [51]. UI and FI frequently coexist (i.e. double incontinence, DI) in our patient population with every tenth patient being affected 6 month post-fracture in our previous study. We demonstrated patients with DI to be an especially vulnerable group with higher disability and functional limitations compared to patients with UI only, and DI was strongly associated with pre-fracture UI [17]. We didn’t examine different subtypes of UI in our previous work, but in light of our new findings, it is likely that the subtype of UI which the patients with DI are affected by, is often either UUI or MUI.

The associated factors of both SUI and UUI converged in MUI, which is to be expected given the condition is defined as a combination of the other two [1]. Patients with MUI were the most vulnerable group in this study. In younger women evaluating UI subtype is important in selecting the appropriate treatment measures [3]. In our patients however, a CGA and rehabilitation plan is key in assessing UI, regardless of its subtype. Specific attention needs to be paid to physical function and mobility with an aim of regaining pre-fracture level. Of note, a multidimensional exercise treatment programme including pelvic floor muscle exercises has been proven to benefit older women not only with SUI but also with UUI and MUI [52]

According to best of our knowledge, this was one of the first studies aimed to examine factors associated with different UI subtypes among older female hip fracture patients. The strengths of our study were its real-world design, systematic data collection, and the comprehensive selection of well-known and standardized instruments with which the outpatient CGA was carried out. In addition, our results are representative of female hip fracture patients given that both patients living in assisted living accommodations or long-term care and having cognitive disorders were included in the study.

We acknowledge some limitations which should be considered when interpreting the results. First, incontinence symptoms were evaluated only with simple questions instead of validated questionnaires, and frequency, severity, time frame, or bother of the symptoms were not included in the data collection. Instead, several other significant assessments were included in the outpatient CGA. Second, comorbidities were not recorded in detail, and thus possible pre-existing urogynecological disorders were not known. Only ASA score represents the general health of the patient. However, ASA score has been established to correlate adequately with Charlson comorbidity index in hip fracture patients [53]. Third, our study concerned only women with hip fracture. We chose to concentrate on women because both hip fractures and continence problems are notably more common in women than in men and the pathophysiology between the sexes differs. Fourth, considering the relatively small sample sizes of the SUI and MUI groups, some caution is due when interpreting our results. Finally, the possibility of selection and survivor bias should be considered given that the data on different UI subtypes were available from less than half of the original study population. Nearly every fifth patient had died before the CGA, and those in poorest of health could not attend the CGA, thus true prevalences of especially UUI and MUI might be higher than presented in this study.

Conclusions

All UI subtypes were associated with modifiable risk factors which should be taken into consideration in the management and rehabilitation of older women with hip fracture. Patients with MUI had most associated factors. In all, comprehensive geriatric assessment is key in assessing UI in older hip fracture patients, regardless of UI subtype.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to limitations of ethical approval involving the patient data and anonymity but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Haylen BT, De Ridder D, Freeman RM et al (2010) An international urogynecological association (IUGA)/international continence society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn 29:4–20

Gibson W, Wagg A (2014) New horizons: urinary incontinence in older people. Age Ageing 43:157–163

Lukacz ES, Santiago-Lastra Y, Albo ME et al (2017) Urinary incontinence in women a review. JAMA 318:1592–1604

Sanses TV, Kudish B, Guralnik JM (2017) The relationship between urinary incontinence, mobility limitations, and disability in older women. Curr Geriatr Rep 6:74–80

Aharony L, De Cock J, Nuotio MS et al (2017) Consensus document on the detection and diagnosis of urinary incontinence in older people. Eur Geriatr Med 8:202–209

Minassian VA, Bazi T, Stewart WF (2017) Clinical epidemiological insights into urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J 28:687–696

Minassian VA, Hagan KA, Erekson E et al (2020) The natural history of urinary incontinence subtypes in the nurses’ health studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 222:163.e1-163.e8

Sung VW, Hampton BS (2009) Epidemiology of pelvic floor dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am 36:421–443

Minassian VA, Yan X, Pilzek AL et al (2018) Does transition of urinary incontinence from one subtype to another represent progression of the disease? Int Urogynecol J 29:1179–1185

Qiu Z, Li W, Huang Y et al (2022) Urinary incontinence and health burden of female patients in China: subtypes, symptom severity and related factors. Geriatr Gerontol Int 22:219–226

Coyne KS, Kvasz M, Ireland AM et al (2012) Urinary incontinence and its relationship to mental health and health-related quality of life in men and women in Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Eur Urol 61:88–95

Drake MJ (2018) Fundamentals of terminology in lower urinary tract function. Neurourol Urodyn 37:S13–S19

Gibson W, Hunter KF, Camicioli R et al (2018) The association between lower urinary tract symptoms and falls: forming a theoretical model for a research agenda. Neurourol Urodyn 37:501–509

Chiarelli PE, Mackenzie LA, Osmotherly PG (2009) Urinary incontinence is associated with an increase in falls: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother 55:89–95

Guzon-Illescas O, Perez Fernandez E, Crespí Villarias N et al (2019) Mortality after osteoporotic hip fracture: incidence, trends, and associated factors. J Orthop Surg Res 14:203

Pajulammi HM, Luukkaala TH, Pihlajamäki HK et al (2016) Decreased glomerular filtration rate estimated by 2009 CKD-EPI equation predicts mortality in older hip fracture population. Injury 47:1536–1542

Hellman-Bronstein AT, Luukkaala TH, Ala-Nissilä SS et al (2022) Factors associated with urinary and double incontinence in a geriatric post-hip fracture assessment in older women. Aging Clin Exp Res 34:1407–1418

Komesu YM, Schrader RM, Ketai LH et al (2016) Epidemiology of mixed, stress, and urgency urinary incontinence in middle-aged/older women: the importance of incontinence history. Int Urogynecol J 27:763–772

Hellman-Bronstein AT, Luukkaala TH, Ala-Nissilä SS et al (2023) Urinary and double incontinence in older women with hip fracture-risk of death and predictors of incident symptoms among survivors in a 1-year prospective cohort study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 107:104901

Jaatinen R, Luukkaala T, Viitanen M et al (2020) Combining diagnostic memory clinic with rehabilitation follow-up after hip fracture. Eur Geriatr Med 11:603–611

Sankar A, Johnson SR, Beattie WS et al (2014) Reliability of the American society of anesthesiologists physical status scale in clinical practice. Br J Anaesth 113:424–432

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, Mchugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients of the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12:189–198

Rubenstein LZ, Harker JO, Salvà A et al (2001) Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 56:366–372

Brown LM, Schinka JA (2005) Development of initial validation of a 15-item informant version of the geriatric depression scale. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr 20:911–918

Lawton MP, Brody EM (1969) Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9:179–186

Viccaro LJ, Perera S, Studenski SA (2011) Is timed up and go better than gait speed in predicting health, function, and falls in older adults? J Am Geriatr Soc 59:887–892

Smith R (1994) Validation and reliability of the elderly mobility scale. Physiotherapy 80:744–747

Alley DE, Shardell MD, Peters KW et al (2014) Grip strength cutpoints for the identification of clinically relevant weakness. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 69:559–566

Nuotio MS, Luukkaala T, Tammela T (2019) Elevated post-void residual volume in a geriatric post-hip fracture assessment in women-associated factors and risk of mortality. Aging Clin Exp Res 31:75–83

Nuotio M, Jylhä M, Luukkaala T et al (2003) Urinary incontinence in a Finnish population aged 70 and over—prevalence of types, associated factors and self-reported treatments. Scand J Prim Health Care 21:182–187

Lee UJ, Feinstein L, Ward JB et al (2021) Prevalence of urinary incontinence among a nationally representative sample of women, 2005–2016: findings from the urologic diseases in America project. J Urol 205:1718–1724

Schreiber Pedersen L, Lose G, Høybye MT et al (2017) Prevalence of urinary incontinence among women and analysis of potential risk factors in Germany and Denmark. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 96:939–948

Abufaraj M, Xu T, Cao C et al (2021) Prevalence and trends in urinary incontinence among women in the United States, 2005–2018. Am J Obstet Gynecol 225:166.e1-166.e12

Lim YM, Lee SR, Choi EJ et al (2018) Urinary incontinence is strongly associated with depression in middle-aged and older Korean women: data from the Korean longitudinal study of ageing. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 220:69–73

Shi TT, Min M, Zhang Y et al (2019) Depression and risk of hip fracture : a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Osteoporos Int 30:1157–1165

Lenze EJ, Munin ÃMC, Skidmore ER et al (2007) Onset of depression in elderly persons after hip fracture: implications for prevention and early intervention of late-life depression. J Am Geriatr Soc 55:81–86

Hellman-Bronstein AT, Luukkaala TH, Ala-Nissilä SS et al (2024) Do urinary and double incontinence predict changes in living arrangements and mobility in older women after hip fracture?—a 1-year prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr 24:100

Fritel X, Lachal L, Cassou B et al (2013) Mobility impairment is associated with urge but not stress urinary incontinence in community-dwelling older women: results from the ossébo study. BJOG 120:1566–1574

Okumatsu K, Osuka Y, Suzuki T et al (2021) Urinary incontinence onset predictors in community-dwelling older women: a prospective cohort study. Geriatr Gerontol Int 21:178–184

Gibson W, Jones A, Hunter K et al (2021) Urinary urgency acts as a source of divided attention leading to changes in gait in older adults with overactive bladder. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257506

Moon S, Chung HS, Yu JM et al (2020) Impact of urinary incontinence on falls in the older population: 2017 national survey of older Koreans. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 90:104158

Chong E, Chan M, Lim WS et al (2018) Frailty predicts incident urinary incontinence among hospitalized older adults—a 1-year prospective cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 19:422–427

Matthews CA, Whitehead WE, Townsend MK et al (2013) Risk factors for urinary, fecal, or dual incontinence in the nurses’ health study. Obstet Gynecol 122:539–545

Marcelissen T, Anding R, Averbeck M et al (2019) Exploring the relation between obesity and urinary incontinence: pathophysiology, clinical implications, and the effect of weight reduction, ICI-RS 2018. Neurourol Urodyn 38:S18-24

Pang H, Xu T, Li Z et al (2022) Remission and transition of female urinary incontinence and its subtypes and the impact of body mass index on this progression: a nationwide population-based 4-year longitudinal study in China. J Urol 208:360–368

Helminen H, Luukkaala T, Saarnio J et al (2017) Changes in nutritional status and associated factors in a geriatric post-hip fracture assessment. Eur Geriatr Med 8:134–139

Bell JJ, Pulle RC, Lee HB et al (2021) Diagnosis of overweight or obese malnutrition spells DOOM for hip fracture patients: a prospective audit. Clin Nutr 40:1905–1910

Lian W, Li F, Huang H et al (2019) Constipation and risk of urinary incontinence in women : a meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J 30:1629–1634

De Giorgio R, Ruggeri E, Stanghellini V et al (2015) Chronic constipation in the elderly : a primer for the gastroenterologist. BMC Gastroenterol 15:130

Coyne KS, Cash B, Kopp Z et al (2011) The prevalence of chronic constipation and faecal incontinence among men and women with symptoms of overactive bladder. BJU Int 107:254–261

Botlero R, Bell RJ, Urquhart DM et al (2011) Prevalence of fecal incontinence and its relationship with urinary incontinence in women living in the community. Menopause 18:685–689

Kim H, Yoshida H, Suzuki T (2011) The effects of multidimensional exercise treatment on community-dwelling elderly Japanese women with stress, urge, and mixed urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 48:1165–1172

Ek S, Meyer AC, Hedström M et al (2022) Comorbidity and the association with 1-year mortality in hip fracture patients: can the ASA score and the charlson comorbidity index be used interchangeably? Aging Clin Exp Res 34:129–136

Acknowledgements

Ms Kaisu Haanpää, RN, is gratefully acknowledged for her expert collecting and saving of the data.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Turku (including Turku University Central Hospital). This work was supported by Research Fund of the Hospital District of Southern Ostrobothnia (VTR111) and the State Research Financing of Seinäjoki Central Hospital (VTR233).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study design was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southern Ostrobothnia. The study complies with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants or their representatives.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hellman-Bronstein, A.T., Luukkaala, T.H., Ala-Nissilä, S.S. et al. Associated factors of stress, urgency, and mixed urinary incontinence in a geriatric outpatient assessment of older women with hip fracture. Eur Geriatr Med (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-024-00997-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-024-00997-w