Abstract

Background

The concept of health care innovation varies across organizations and countries. Harmonizing the definitions of innovation can augment the discovery of new therapies, minimize costs, and streamline drug development and approval processes. A systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted to gather insights surrounding different elements of innovation in the USA, the UK, France, Germany, and Japan. The SLR identified studies that have defined innovation and captured the types of incentives provided to promote innovation.

Methods

The MEDLINE, Embase, and EconLit databases were searched via the OVID SP platform on October 22, 2020. A secondary desk search literature review was performed to identify additional information of interest in regional languages: French, German, and Japanese. All the relevant literature in English was screened using the Linguamatics natural language processing (NLP) tool, except for articles from EconLit, which were screened manually using structured search strategies. Articles that describe a definition of innovation or refer to a definition of innovation published were included. All full-text articles were reviewed manually, and two reviewers independently screened the full texts for eligibility.

Results

After screening, 90 articles were considered to meet the SLR objectives. The most common dimension of innovation identified was therapeutic benefit as a measure of innovation, followed by newness and novelty aspects of innovations. Incentives around exclusivities were found to be the most prevalent in the data set, followed by rewards and premiums. Among the different therapy areas, the largest number of innovations was targeted at oncology.

Conclusions

This SLR highlights the lack of a unified definition of innovation among regulatory authorities and health technology assessment bodies in five countries, and variation in the types of incentives associated with innovation. The targeted countries cover different dimensions of definition and incentives of innovation at varying levels, with a few focused on specific therapy areas. Harmonization and consensus for innovation would be needed across countries because drug development is a global undertaking. This SLR envisages a more holistic approach to evaluation, wherein the value provided to patients and health systems is accounted for. The results of this SLR will help to promote broader discussion among different stakeholders and decision makers across countries to identify gaps in policies and develop sustainable strategies to promote innovation for pharmaceutical products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This systematic literature review (SLR) investigated the measure of innovativeness of medicinal products and it was concluded that the most common dimension of innovation identified was therapeutic benefit. |

Further, the SLR highlighted the lack of unified definition of innovation across the target countries and the broad variation of incentives related to the innovation. |

The SLR findings were that harmonization and consensus for innovation are non-existent across countries, although drug development is globally performed. |

1 Introduction

The global burden of diseases has been on the rise for the last several decades [1]. Preventing, treating, and tackling diseases along with the associated risk factors can offer major socioeconomic benefits [2, 3]. The myriad of global health challenges can be addressed by catalyzation of innovation in healthcare [4]. Factors such as changing patient needs, persistent and long-term health problems, budgetary constraints, technological changes, and unstable operational landscapes demand innovation in health care to enhance patient outcomes [5]. Innovation is important to increase life expectancy, quality of life, treatment options, affordability of treatment, and the efficiency of health care systems [6]. Thus, fostering innovation ensures health care benefits for patients, caregivers, clinicians, and other stakeholders alike [6].

Mulgan et al. describe the different degrees of innovation as incremental, radical, and transformative. In their papers [5, 7], they explore ways in which the concept of innovation varies across different individuals and organizations, thus accounting for the lack of a unified definition of innovation [8,9,10,11,12]. One such definition covering innovative aspects with respect to the product, process, or structure states that “health care innovation can be defined as the introduction of a new concept, idea, service, process, or product aimed at improving treatment, diagnosis, education, outreach, prevention and research, and with the long-term goals of improving quality, safety, outcomes, efficiency, and costs” [6]. A systematic literature review (SLR) conducted by de Solà-Morales et al. investigated how innovation is defined with respect to new medicines and evaluated the extent to which published definitions of innovation incorporate the impact of new medicines on health care costs [13]. The SLR revealed that most definitions of innovation generally consider the therapeutic benefit offered by a new product to be the most important factor for categorizing a new medicine as innovative. However, quantification of therapeutic benefit is consistently obscured by definitions and is left to subjective interpretation [13, 14].

The definition of what is considered an innovation, as well as the criteria used for measuring innovativeness by governments, policymakers, and stakeholders also varies from country to country—creating challenges for these stakeholders working across different regions on how to reward innovation appropriately. Also, the definition of innovation differs with respect to pharmaceuticals, devices, surgical techniques, and services [13]. With constant changes in health care and the lack of clarity associated with the term innovation, it is being very loosely used and applied [15]. Streamlining the definition of innovation will help manufacturers develop new treatment methods, reduce associated costs, and simplify the drug development and approval process, all of which will eventually benefit patients and the public. A functional, transparent, dynamic system involving regulators, policymakers, and stakeholders across the spectrum will play a vital role in defining and fostering appropriate innovation.

The aims of this SLR were to identify articles that discuss the definition of health care innovation and to summarize how innovation is defined and incentivized across five high-income countries. These countries were selected on the basis of: countries that are among the top 10 in gross domestic product (namely, the USA, the UK, France, Germany, and Japan) that have well-established regulatory and value assessment systems, as well as abundant evaluation evidence.

2 Methods

This SLR was conducted in accordance with the evidence-based minimum set of items essential for transparent reporting of a systematic review called Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines—in terms of eligibility criteria, information sources, search strategy, selection process, data collection process, data items, study risk of bias assessment, and effect measures [16, 17]. The SLR was conducted to identify articles that defined innovation, and it adopted the Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type (SPIDER) framework to shape the search strategy [18,19,20].

2.1 Search Strategy

The inclusion criteria for the scope of this review included the SPIDER criteria and are shown in Table 1. Articles containing at least one search term in each of the two elements of Sample (medicinal products/drugs), Phenomenon of Interest (innovation), and Evaluation (definition/evaluation) were included for title/abstract screening. Three electronic databases (MEDLINE, Embase, and EconLit) were searched via the OVID SP platform on October 22, 2020. A similar SLR conducted by de Solà-Morales et al. used two elements for search terms: Sample (drugs/therapies) and Phenomenon of Interest (innovation) [13]. In this review, we added new terms in addition to those used by de Solà-Morales et al. This included expanding upon the elements of evaluation (definition/algorithm), which was found to be important in this SLR for identifying the definition of innovation. For example, “Incentive,” “Algorithm,” and “Pricing” were added for the definition of innovation. The complete list of search terms used is shown in Tables S1–S3 in Online Resource 1. The search strategy included locating articles that describe a definition of innovation or refer to a definition of innovation published using the defined search terms. Articles published from January 2010 to October 2020 (inclusive) were included.

2.2 Study Selection (Using Text Mining Tool and Manually)

For this SLR, only the screening of titles/abstracts indexed in MEDLINE and Embase was performed using the Linguamatics NLP tool. Articles from EconLit were screened manually using structured search strategies. Included articles from all three databases were further manually screened for titles/abstracts relevant to the review. Manually screened articles were reviewed by two independent reviewers (double review) to increase the reliability of the process. Disagreements were resolved by consensus whenever possible. A third reviewer was brought in for further conflict resolution when needed.

The search hits from the three databases were combined and de-duplication performed using Microsoft Excel at the manual title/abstract screening stage. Articles specifically describing definitions for medical devices, surgical techniques, or other services delivered were excluded, but those that fell under general descriptions may have been included.

2.3 Secondary Desk Search

Secondary desk searches of relevant websites were conducted using a similar methodology to de Solà-Morales et al [13], to identify stated policies or methods for assessing innovation in English or local languages (French, German, and Japanese). The selection criteria for the secondary desk search were similar to those for the SLR. All secondary desk search results were screened and limited to the first 100 relevant hits as a single review process. The websites searched to identify literature from the secondary desk search and for country-specific information on the definition of innovation are listed in Table 2. Searches were conducted using online portals on government and academic society/agency reports and guidelines. The following keywords were used in various combinations to search and retrieve relevant secondary desk search literature information from the organizations: drug, innovative, innovation, definition, and medicine.

Keywords were entered into the search boxes of the targeted online platforms. The returned documents (in PDF and Microsoft Word formats) were passed through NLP, which analyzed them for relevance following the manual search depending on the language and copyright restrictions. The search method for the agencies listed in Table 2 was done using the keywords “Innovation,” “Innovative,” and “Innovant,” and the relevant pages were then screened. The website searches were not fully systematic. Therefore, the definitions and incentives identified through the secondary desk search were not included in the analysis of the dimensions of innovation and types of incentives.

2.4 Data Extraction

The data extraction template was developed in Microsoft Excel to capture relevant articles. Data were extracted based on study details, study overview, definitions, and relevant outcomes, such as criteria for innovation, as shown in Table 3. Innovation extraction fields were not limited to “Definition,” but relevant information such as “Algorithm,” “Agency,” “Therapy area,” and “Recommendation” were also included for extraction from the articles. For the secondary desk search, a Microsoft Excel database was generated for data extraction and included, but was not limited to, the following innovation-related information: organization, acronym, country, website, search method, findings (conclusions elucidated from the investigation), and definition.

Full-text articles were reviewed independently by one reviewer (single review) followed by a quality control check to increase the reliability of the process.

2.5 Data Analysis

Several definitions of innovation were identified in the SLR data extraction process and similar terms were grouped and counted by country after mapping them into ten different dimensions of innovation, as shown in Table 4. The dimensions of innovation were similar to those used by de Solà-Morales et al [13] (Administration, Availability of existing treatment, Clinical evidence, Cost, Newness, Novelty, Other, Safety, Therapeutic benefit, and Unmet need) with the only difference being “Access” replacing “Other” in this SLR.

The incentives were also grouped in order to explore what types of incentives were mentioned about promoting innovation during the period of SLR, because “Incentive” and “Pricing” were added for the search terms to identify the definition of innovation. The identified incentive terms, such as patent protection or market exclusivities, accelerated regulatory approvals and any financial benefits (e.g., R&D tax credit, price premium, etc.) were grouped into three categories (Exclusivities, Fast/ Priority track, and Rewards/Premiums), as shown in Table 4.

The data for dimensions of innovation and types of incentives were analyzed and presented as number of occurrences within the identified definitions and incentives. Percentages were calculated as the proportion of articles that contributed to each dimension. Data were also tabulated by country of interest.

3 Results

In total, 25,420 articles were identified through database searches from Embase and MEDLINE, and 2895 were identified from EconLit. For Embase and MEDLINE, title and abstract screening were performed automatically using NLP, whereas articles from EconLit were screened manually. There were many duplicates because some journals are indexed in multiple databases and the same articles were retrieved 2–3 times; additionally, there were many instances where the only differences between articles retrieved were in the punctuation of the title, while the rest of the content was duplicated, and such cases were was identified during title/abstract screening. After removing duplicates from the records, the titles, and abstracts of 4229 unique articles were screened. In total, 706 articles were identified as being potentially relevant to the objectives of this review, and full texts of the publications were obtained. Articles were further excluded based on geography, resulting in the inclusion of 201 articles for the qualitative synthesis of different evaluations listed under the SPIDER criteria in Table 1. A detailed flow diagram of the study selection process is shown in Fig. 1. Considering the exhaustive information available from the 201 articles, we focused on articles that had definitions of innovation and incentives for understanding the different dimensions of innovation and the methods of promoting innovation. Evidence from 65 articles focusing on definitions of innovation and 32 articles on incentives (definitions provided in Table 4) to promote innovation (7 articles had both definitions of innovation and incentives) for a total of 90 articles are presented and their references are provided in Tables S4 and S6 in Online Resource 1.

3.1 Definitions of Innovation

Innovation in health care is defined differently by different countries and regulatory authorities. Several criteria are used to define innovation using both health and non-health elements that incorporate clinical usefulness and the process through which innovation arises. A total of 65 instances from the USA, the UK, France, Germany, Japan, and “multi-country” were identified that defined innovation, with the most studies coming from the USA (33 articles), followed by the UK (9 articles), France (8 articles), Germany (4 articles), Japan (2 articles), and “multi-country” (9 articles). Any definition used by more than one country identified in an article is defined as “multi-country”. On average, five to six articles were published each year and of 65 articles, 38 (58%) were published from 2010 to 2015 and 27 (42%) were published from 2016 to 2020. Several articles referred to the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) definition of innovation in the USA [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s (NICE) including Kennedy’s short study for NICE in the UK [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] and the Amelioration du service medical rendu’s (ASMR, improvement of medical services rendered) in France [38,39,40,41,42]. The most common factor considered while defining innovation was therapeutic benefit as a measure of innovativeness across countries. The different studies describing the different definitions of innovation are summarized in Table S4 in Online Resource 1.

USA In the USA, an effective and safe treatment for a disease is defined as an innovative treatment [43], and innovation is defined in terms of new drugs that deliver substantial health benefits to patients and are approved by the FDA [41, 44]. Improvement or additional smaller health benefits over existing therapies are defined as incremental innovation [23, 26]. The FDA classifies new drugs according to the novelty of their chemical substance (new molecular entities or new active ingredients vs updates) and therapeutic potential, which determines the review speed (priority review for drugs fulfilling a high medical need vs standard review) [26]. Based on the FDA’s new drug review type classification, the innovation is further classified as radical, technological breakthrough, market breakthrough, and incremental innovation [23, 26]. Precision medicine in cancer treatment has been recognized by the FDA as innovation [27]. Recently, Smith et al. reported that transient conjugation technologies developed to address unmet needs have been expected to be known as an innovative approach [45].

UK In the UK, “innovation in the area where there is an unmet need that improves outcomes and ensures value for money to the National Health Service (NHS) with better access to effective medicines” is defined as innovation [46]. According to NICE, innovation is defined as a treatment that produces demonstrable and distinctive benefits of a substantial nature that may not be adequately captured in the quality-of-life measure used [31, 32]. Kennedy in his short study for NICE [30, 33, 34], suggested that innovation is something that is new, improves on existing interventions, and offers something more in the way of a step change in terms of outcomes for patients. According to Quinn et al, from the policy perspective, England’s Cancer Drugs Fund considers oncology products that offer substantial increases in overall survival (OS), and the magnitude of the OS benefit, as key elements in the definition of innovation [47].

France In France, a new drug is reimbursed after carefully reviewing its medical benefit and medical innovation. The level of innovation a drug brings to the market is determined by the drug’s improvement of medical benefit or ASMR compared to the current standard of care. The ASMR assigns ratings from I to V, based on the level of improvement; a drug with an ASMR level I, II or III is considered an innovative drug [38, 39]. Iordatii et al. define innovation as a new therapeutic option to treat a health problem for which there may already be an existing therapeutic arsenal that is targeting a disease, a symptom, or a risk factor. Innovation may lead to treatments that are easier to monitor, or doses that are easier to adjust for physicians [48]. According to Gonçalves et al, new therapeutic molecules that have the potential to radically transform the management and course of cancer, a product that—through a radical change—brings something new and that has the potential to constitute treatment in a situation where it did not exist previously or to improve clinically, can be defined as innovative. Also, an old drug for which new therapeutic activity has just been identified may be considered as innovative [49, 50].

Germany The German government considers innovative medicines as new therapeutic entities with additional benefits over existing treatments and that improve the quality of life in addition to offering good value for money. Whether innovative medicines have additional benefits is determined through early benefit assessment under the law within the statutory health care system (Arzneimittelmarktneuordnungsgesetz, AMNOG, English translation: "Pharmaceuticals Market Reorganization Act") by the German Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) [51]. Specialists groups classified innovative drugs as leap innovations, where a drug represents a completely new type of active ingredient, or as step innovations that can be a further development or improvement of a known active ingredient [52].

Japan In Japan, the Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (JPMA) identifies any drugs discovered based on research and development (R&D), and employing advanced technologies that address patients’ needs and clinical needs, as innovative drugs [53].

3.2 Dimensions of Innovation

Several definitions of innovation were identified in this review, and similar definition terms were grouped and mapped into ten different dimension categories, as shown in Fig. 2 and Table 5. Among the different dimensions of innovation, therapeutic benefit was the most frequently reported dimension (46 articles), including 100% of studies from Japan and the UK, followed by 89% from “multi-country”, 88% from France, 75% from Germany, and 52% from the USA. Other commonly reported dimensions of innovation were newness (32 articles), novelty (20 articles), cost (13 articles), and unmet need (12 articles). The least reported dimension was access, with only one article from the UK [46]. Administration is one of the least reported dimensions, with only five articles, of which three were from France, one was from the UK, and the other was “multi-country” [33, 40, 48, 49, 54]. Improvement in administration (formulation) of drugs for cancer and development of new antiretroviral drugs with simpler dosing regimens was identified from France [49, 55]. Country-wise assessments of included datasets about the definition and dimension of innovation are shown in Table S4 in Online Resource 1. A summary of the different dimensions and types of incentives identified across the SLR evidence is presented in Table S5 in Online Resource 1.

3.3 Types of Incentives for Innovation

A total of 32 articles were identified. Of these, 18 articles from the USA, 11 from “multi-country”, and 1 each from the UK, France, and Japan provided information on incentives for innovation, and different countries provided different incentives to encourage innovation, as shown in Table 6 and Table S6 in Online Resource 1. The different incentive categories “rewards and premiums, exclusivities, and priority/fast-track reviews” and their definitions are listed in Table 4 and the numbers by country are provided in Table 6.

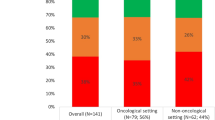

Among the selected types of incentives, exclusivities formed the most reported category of incentive (21 articles). Exclusivities are patents to protect original compounds against generics, including incentives provided for innovations targeted towards pediatric populations and rare diseases (including orphan drugs). Among the 21 articles about exclusivities, 11, 10 and 5 articles mention exclusivities related to rare diseases, pediatric populations, and biologics, respectively. Rewards/premiums formed the second most common form of incentive, which captures any financial benefit provided for innovation, such as R&D tax credit, price premium, etc. (20 articles). Incentive for priority/fast-track review was found to be the area of least focus within our dataset (9 articles), as shown in Fig. 3. Only articles from the USA included all types of incentives. As per our findings, articles specific to one country showed that France includes four types of incentives except priority/fast-track review, and the UK and Japan include incentives associated with reward/premiums, while Germany included no incentives at all. However, 11 articles falling under the “multi-country” category showed a mixture of incentives, with 5 of 11 articles including exclusivities related to European Union (EU) law which apply to the UK, France and Germany [56,57,58,59,60].

In the USA, several legislative programs (e.g., the Bayh-Dole Act, the Hatch-Waxman Act, the Orphan Drug Act, pediatric exclusivity protection, the FDA Modernization Act, the Affordable Care Act) have been enacted to offer incentives by providing mainly exclusivity to stimulate innovation [56, 57, 61,62,63,64]. The Hatch-Waxman Act (the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act in the USA) promotes filing for generic drugs with an abbreviated application. However, the Act provides each new approved drug 5 years of regulatory protection, that is “data exclusivity”, for new chemical entities and 3 years for new indication and dose-to-drug innovators as a trade-off [58]. Similar to this, the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act included in the Affordable Care Act allows abbreviated approval of “follow on” biologics while the Act provides 12 years of data exclusivity for new biologics [62]. The Orphan Drug Act provides 7 years of market exclusivity and 50% of a R&D tax credit. The pediatric exclusivity protection provides 6 additional months of market exclusivity if pediatric studies are requested and completed [24, 56, 58, 59, 61, 62, 65, 66]. Alexander et al. pointed out that apart from incentivizing new drugs/biologics, providing exclusivity for common disease drugs with unequivocal therapeutic breakthroughs could also stimulate the development of innovative therapies with substantial public health benefits [67]. The reward premium includes Medicare part D coverage, prescription drug insurance coverage in the USA, which was expanded to cover all drugs in 6 protected classes such as oncology drugs that fueled pharmaceutical innovation, and tax credit for R&D [41, 44, 58, 61, 65, 66, 68].

In the EU, including the UK, France, and Germany, the patent term can be extended through supplementary protection certificates up to a maximum of 5 years with a six-month extension for pediatric investigational plans [58]. The EU provides for a data exclusivity period of 8 years and 2 extra years for market exclusivity, and also provides 1-year potential extension of market exclusivity [56,57,58,59,60]. Orphan drug manufacturers in the EU stand to benefit from 10 years of orphan drug exclusivity that may extend up to 12 years (instead of 10.5 years) if pediatric trial data are included [58].

In France, the price setting and determining the reimbursement rate of drugs are the SMR and ASMR ratings that assess the medical benefit and the innovation rate of the drug. For innovative drugs with ASMR IV and I to III ratings, the price level will be maintained for 5 years and will not be lower than the price level in the 4 main countries: Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK. Drugs with an ASMR rating from I to III and which are granted an extension of indication, and pediatric medicines based on a pediatric investigation plan, benefit from an extension of 1 year [69].

In the UK, according to Hughes, the nature of value-based pricing (VBP) will reward clinically useful innovative drugs at the highest prices they may command [70].

In Japan, there is a price premium system by MHLW to incentivize innovation and the Orphan Drug/Medical Device Designation System, which provides tax credit on research expenses, extended market exclusivity of 10 years, and a priority review [68].

Country-wise assessments of included datasets show how different countries aim to promote innovation by providing regional incentives of varying degrees (captured as part of this review), as shown in Table S6 in Online Resource 1.

3.4 Therapeutic Area Focus

The SLR also identified aspects of innovation that were specific to certain therapy areas presented in Table 7. The most commonly reported therapy area was oncology (9 articles), including 3 studies from the USA [27, 41, 44] 2 articles from France [49, 71], and 4 “multi-country” articles [32, 47, 72, 73]. New and innovative drugs that offer substantial health benefits over existing treatments by significant increase or improvement in overall survival (OS) or progression free survival (PFS) are some of the frequently reported definitions of innovation in cancer [41, 44, 47]. Innovation related to therapeutic benefit or clinical benefit, and precision medicine or personalized medicine, is among the main drivers in the area of oncology [27, 32].

In terms of incentives specific to therapy areas, Bennette et al. reported that Medicare Part D coverage provides strong incentives for pharmaceutical manufacturers resulting in the increase of investments to develop new oral chemotherapy agents and targeting diseases of the elderly in the USA [41, 44]. However, these do not show the incremental clinical benefits over existing therapies. Bennette et al. concluded that innovators have the incentive to bring to market innovations with smaller health benefits, because the coverage is not linked to clinical benefit and has no price constraints, and no checks to eliminate the drug from the formulary [41, 44].

Årdal et al. reported the evaluation of four potential financing models (diagnosis-related group carve-out, stewardship taxes, transferable exclusivity voucher, and a European-based “pay or play” model) as pull incentives to ensure access and utilization of new antibiotics that meet unmet public health needs from a European perspective. The definitions of each financial model are provided in Table S6 in Online Resource 1. They conclude that a transferable exclusivity voucher is the only financing mechanism that could finance antibiotic innovation on its own, although it has an extremely high cost and with little guarantee of access, and for the remaining three financing models, it should be considered in combination [74, 75].

In the USA, the EU, and Japan, the orphan drug designation provides incentives to innovate in the rare diseases area. The details are described in Sect. 3.3 Types of Incentives for Innovation.

3.5 Additional Evidence from Secondary Desk Search Literature

A secondary desk literature search was conducted for documents in English, Japanese, French, and German (Table S7 in Online Resource 1). In English, a total of 23 documents were identified by manual website search of which 15 documents from 7 agencies/governmental organizations aligned with the review objectives were included. Of the 23 documents, 8 documents were excluded for nonrelevance. For French and German documents, no relevant information was found during manual searches from the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare (IQWiG) and the Haute Autorité de santé (HAS). Information from the International Health Economics Association (iHEA) did not meet the timeline criteria for the search (2010–2020) and was not included. For Japan, 59 documents were identified in Japanese language from agencies such as Institute for Health Economics and Policy (IHEP), the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), and the CiNii database. Of these, 9 duplicates and 36 nonrelevant documents were removed. A total of 14 documents were included for data extraction. Refer to Table S7 in Online Resource 1 for more details on the secondary desk search literature evidence.

The English literature search retrieved definitions and descriptions associated with innovation, new products and/or technologies, the process of innovation, and the level of innovativeness. Data were retrieved from countries of interest in the form of local opinions, as well as from international organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and Health Technology Assessment International (HTAi).

In the context of this review, innovation was defined by the WHO and the European Network for Health Technology Assessment (EUnetHTA) specifically as “service innovation,” “transformative innovation,” “major innovation,” and “health innovation” [76,77,78]. These definitions, in a broad sense, focus on the way an innovation improves health outcomes for patients. Of note, HAS and HTAi consider products as innovative when there is an improvement over existing products/treatments leading to enhanced clinical benefits for patients [79, 80]. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), NICE, HTAi, NHS, and WHO consider a technology to be innovative when it is new and makes a substantial impact by showing a step change in terms of outcomes for patients [79, 81, 82] and processes in health care delivery [77, 81, 83, 84].

In terms of defining “new” and “emerging” technologies, HTAi defines “a health technology that is in the launch, early post-marketing or early diffusion stages” as “new” and “a health technology that has not yet been adopted within the health care system. Pharmaceuticals that are in Phase II or III clinical trials, or in the pre-launch stage; and medical devices that are in the pre-marketing stage” as “emerging” [79, 83, 85]. The EUnetHTA definition focused on the large impact that innovation has on patient health, public health, or health care systems, and those that transform the way care is provided. The EUnetHTA suggests that a precise definition of emerging technologies is not provided under the EU proposal and that a common definition of “innovative health technology” is currently lacking [76].

The WHO’s definition focused on innovative aspects that cover administrative efficiency, cost effectiveness, improved health policies, systems, products, and technologies [77]. In addition, the AHRQ covered the aspect of cost-effectiveness of care. In contrast, the iHEA defined major innovation as first agents with a particular clinical action or pharmacological action, or as the first with the same clinical effect as existing agents but with a different mechanism of pharmacological action.

In Japan, innovative drugs are evaluated as price premiums and the MHLW pointed out the need for developing innovative drugs within Japan, identifying how to appropriately evaluate them, and implementing methods to promote practical applications of these innovative drugs [86,87,88,89]. For a thorough review, related articles from the CiNii database were also included [90, 91]. The findings suggest governmental institutional reforms, policies, and long-term strategies focusing on measures such as basic research, clinical trials, approval processes, strengthening international competitiveness, and the pricing system [90,91,92,93,94,95,96]. Japan has a unique pricing system set by the MHLW that is different from the USA and Europe. If one or more of the following factors are present, one or more premiums may be added to the proposed list price: innovativeness/usefulness premiums, marketability premiums (in terms of orphan drugs) (5–20%), pediatric indication premiums (products explicitly include those for children) (5–20%). The criteria for the innovation premiums (70–120%) are granted if all the following criteria are met: (i) new and clinically relevant mechanism of action, (ii) higher efficacy or safety, and (iii) improvement of treatment. If two of three criteria are met, usefulness premium I is granted (35–60%), and if one of four criteria (i, ii, iii plus iv: medically useful improvement of formulation) is met, usefulness premium II is granted (5–30%). The pricing system includes a premium rule for promoting the creation of new drugs and the elimination of off-label drugs, which maintains the initial price until the patent expires for drugs [67, 87, 92, 97]. Sakigake (meaning a pioneer or forerunner in Japanese) designation premiums are products designated as subject to the priority review system and, in addition, price premium (10–20%) [87].

4 Discussion

4.1 Systematic Literature Review (SLR) Findings

Our findings highlight the lack of a unified definition of innovation across countries and variation in the types of incentives associated with innovation. However, there was a common pattern observed across the reviewed countries regarding the definition of innovation, in terms of either innovative medical products or processes. Some definitions occurred more than once; in particular, the FDA classification in the USA and the approach used by NICE or Kennedy’s short study for NICE in England, and ASMR in France were mentioned in several publications. The most common factor considered while defining innovation was therapeutic benefit as a measure of innovativeness, followed by newness and novelty aspects of medical innovations. France and the USA are the only countries to cover precision medicine as one of the aspects for innovation. Not one of the selected countries covered all the dimensions considered in this review.

In this review, incentives around exclusivities were the most frequent, followed by rewards and premiums for innovation.

There is little agreement on what characteristics of new medicines, other than therapeutic benefit, constitute rewardable innovation. Although exclusivity is recognized as a powerful incentive for innovation, a few authors expressed concerns that exclusivity does not relate to therapeutic benefit and leads to the development of so called “me-too drugs” with smaller health benefits over existing therapies rather than breakthrough products due to higher investment risk and comparatively lower incentives for these products [24, 59, 98].

4.2 Similarities to and Differences from Previous Studies

We noticed several similarities with previous studies, such as dimensions of definitions, methodology of data extraction, and algorithms for assessing innovation. Measurement of therapeutic benefit, including survival, improvement in health outcomes, efficacy, improvement in patients’ lives, and increased life expectancy and quality of life, saw similar trends to those reported in the past [25, 43, 99,100,101]. This SLR shows the basis of the assessment on innovativeness of an innovation, how processes and products are defined as innovative, and additionally identifies gene therapy as an innovative therapy [73].

Our SLR captured the factors impacting the cost and price of an innovation and the relationship between cost and access; of note, this relationship was not explored in previous studies. The uniqueness of this SLR also lies in the fact that it is the only SLR to focus on the different types of incentives for innovation across the geographies of interest.

Our SLR extended the study period to 2020 from the review by de Solà-Morales et al [13]. Based on our data, we found that costs as a dimension occurred more frequently, especially in recent years, with 13 articles defining cost as a dimension of innovation in this SLR, when compared to only 2 articles in the paper by de Solà-Morales and colleagues. In the previous review, cost meant only “acceptable cost”; however, in recent papers, the cost meant “expensive” and “value for money” in addition to "acceptable cost", which are described as innovative medicines and are often expensive and have higher treatment costs, or innovative medicines that improve outcomes and represent value for money. The trends for incentives during the first half of the period (2010–2015), which is a subject in the previous review, showed that exclusivities (n = 15, 71%) and priority/fast-track review (n = 6, 67%) were high. During the latter half of the period (2016–2020), rewards/premiums have slightly increased and they included insurance coverage/reimbursement, tax credit or financing model suggestions. This trend indicates recent awareness of the interest in price and the increasing emphasis on costs due to expensive drugs, as seen in this SLR. Besides cost, unmet needs have also increased health care expenditures recently probably due to the focus on pharmaceutical development for rare disease conditions.

Of note, countries such as Italy and Sweden that were included in the review by de Solà-Morales et al, were not among the five countries investigated in this SLR.

4.3 Trends by Country

This SLR investigated ways in which different countries defined innovation. Data showed that different countries had different criteria for defining innovation, and there was no consensus on a single definition for innovation among the target countries (USA, UK, France, Germany, and Japan); this is consistent with findings from the previous SLR by de Solà-Morales and colleagues. However, there were common definitions of innovation considered by most of the countries, such as new molecular entities (NMEs) and drugs with added benefits over existing treatments. From our reviewed articles, we found that innovation is defined by the regulatory agency, the FDA, in the USA, and by the HTA bodies in the UK and France. We assume that this is because there is no official HTA body in the USA, while HTA bodies assessed the values of drugs, such as additional therapeutic benefits and cost-effectiveness, in the UK and France.

While therapeutic benefit was the major consideration, literature from the UK and the USA suggests a more holistic approach to evaluation, wherein the value provided to patients and health systems is accounted for. The US FDA defines innovation by classifying a drug as an NME or an update and its therapeutic potential. Based on this, the FDA determines the review speed: drugs fulfilling a high medical need receive priority review. According to NICE, innovation in the UK is defined as something that offers a step change in terms of patient outcomes. The HAS defines innovation in France as any product claimed by its manufacturer to offer moderate to major improvement in clinical benefit compared to existing treatments. From the perspective of evaluating innovation, France has the standard ASMR framework on therapeutic benefit and Germany evaluates additional benefit through early benefit assessment under AMNOG, while the UK has a standard approach to calculating costs and benefits in the form of quality-adjusted life-years.

Incentivizing new treatments has been considered beneficial to stimulate innovation across countries. A key challenge to innovation is a misalignment of investments, rewards, and therapeutic outcomes. Among the selected countries included in this review, incentives around exclusivities are highest, followed by rewards and premiums for innovation. There were very few articles covering the incentive of priority/fast-track review. In the USA and the EU, similar patent protection and data exclusivity rights exist against generic entries for small molecules and biological drugs to stimulate innovation by rewarding inventors with temporary monopolies over their innovations in order to recoup their R&D expenditures. The market exclusivity rights are also granted for orphan drugs and pediatric indications to stimulate their R&D. In the UK, the data exclusivity and market protection periods have been transposed into UK law by the Human Medicines Regulation 2012 (SI 2012/1916) after Brexit. Insurance coverage such as Medicare Part D, tax credits for R&D, and financing models are a few rewards that encourage innovation in the USA. The pricing premium is seen only in Japan. Literature from the UK describes value-based pricing [31, 46, 70, 102] which is considered as a reward for clinically useful innovative drugs. In this approach the reimbursement or pricing depends on the therapeutic value of the product established in relation to cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) and is expected to ensure sustainable financing of innovative therapies. However, Drummond and Towse pointed out that value-based pricing might be inappropriate in the pricing of treatments for some cases such as ultra-rare diseases and gene therapy [103]. Moreno and Ray reported that the role of CEA in incentivizing innovation is controversial because it may underestimate the value of innovation [94]. Kyle et al. reported that in France, although ASMR assesses the innovation level of drugs, there is no strong relationship between the pricing and ASMR rating [59]. These reports suggest that innovation is not properly rewarded by pricing in Europe. Only the USA has a transferable priority review voucher to stimulate R&D for pediatric indications and neglected diseases that are common in tropical countries for which a relative lack of treatments are available. The USA had more studies reporting incentives compared to other countries and included all types of incentives, while no incentives were reported in Germany.

4.4 Strengths and Limitations

In traditional SLRs, titles and abstracts of published literature are screened using keyword searches and the retrieved documents are manually reviewed for relevant literature. Whereas, text mining is an artificial intelligence technology, such as that developed by Linguamatics, that uses natural language processing (NLP) to examine large collections of documents to extract facts, relationships, and assertions that would otherwise remain buried in the large body of text. Of note, NLP converts the extracted key information from text into quantitative, actionable insights [104,105,106,107,108]. The advantage of NLP is that it can analyze practically unlimited amounts of text-based data without fatigue, in a consistent, unbiased manner. Our SLR conducted a comprehensive search using NLP as an initial step in order to review many articles and provide exhaustive evidence, which comprised 90 studies—including conference abstracts from 2010 to 2020. The advantage of screening citations using NLP is that it yields high sensitivity and good specificity; however, the limitation is that it is not 100% reliable. A key strength of our review was that literature was screened not only in English but also in local languages since a considerable amount of publicly available information for France, Germany, and Japan are only available in local languages. However, this review targeted only five high-income countries (USA, UK, France, Germany, and Japan), and therefore the results cannot be applied to other countries such as China, India, or other developing countries. In this SLR, an analysis of the common features of incentive structures could not be performed due to the high variability seen between the countries. In addition, for the secondary desk search, only articles found on the internet were included in the review, which may have excluded regulatory materials that are not available on the internet; thus, a more comprehensive review would be needed in the future. All the regulatory and HTA organizations’ websites were searched and useful information was retrieved, but some organizations such as EMA were underrepresented in this SLR as no relevant information was retrieved.

4.5 Future Consideration

Further research is needed to generate evidence that will lead to a unified dimension to define innovation and provide appropriate incentives for innovation. This will stimulate R&D, speed access to newer technologies, and increase the dynamic efficiency of society in terms of medicine, health, and the economy. To ensure that, it is necessary to promote innovation globally, and it will be crucial to collaborate internationally on harmonizing definitions of innovation and assessment criteria across countries. Medicinal product development or Clinical development of drugs is led by the global companies; hence, it would be a good idea if these companies or the industry associations also led the discussion on harmonizing the definition of innovation. International non-profit organizations would also be key stakeholders for the discussion. There are many examples of how sharing knowledge and resources across countries has helped everyone involved, as seen during the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Such cross-country collaborations would provide a platform for all health care leaders to focus on common goals for innovation. To promote innovation, the following items need to be discussed globally: 1) which incentives are actually effective in promoting the discovery and development of innovative medicines, 2) how to finance incentives for promoting innovation and how to allocate limited financial resources to innovative drugs considering affordability; 3) how to assess innovation against future risks such as emerging infectious diseases and antimicrobial resistance, including international collaboration; and 4) how to incorporate patients’ opinions. In summary, it is important to harmonize definitions of innovation and assessment criteria across countries to maximize the benefits of everyone involved from innovation to this end, and thus there is a need for more research in this area.

5 Conclusion

This SLR summarizes a few key aspects regarding definitions of innovation and the types of incentives promoted in key countries. In summary, there is a growing interest in innovative drugs and technologies, improving efficiency of health care. To promote innovation globally, international collaboration on defining innovation may be needed. Our review found common definitions of innovation considered by most countries, such as NMEs and drugs with added benefits over existing treatments, and that the USA, the UK, and France had their own definitions of innovation. In the USA, the EU, and Japan, the exclusivity rights for new medicines are provided as the incentives for innovation to recoup R&D expenditures. However, these exclusivities are not always related to the additional benefits. An explicit definition of innovation across countries will help to develop and implement policy frameworks for evaluating and promoting innovation. The results of this review will help promote broader discussion among different stakeholders and decision makers to identify gaps in policies and to develop sustainable strategies to promote holistic innovation.

References

Murray, Christopher J. L, Lopez, Alan D, World Health Organization, World Bank & Harvard School of Public Health. (1996). The Global burden of disease : a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020 : summary / edited by Christopher J. L. Murray, Alan D. Lopez. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/41864.

Merkur S, Sassi F, McDaid D. Promoting health, preventing disease: is there an economic case? 2013, ISSN 2077-1584 [cited 2021 21 August]; https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/235966/e96956.pdf.

Murray CJ, Barber RM, Foreman KJ, Abbasoglu Ozgoren A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990–2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet. 2015;386(10009):2145–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)61340-x.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Global Health; Committee on Global Health and the Future of the United States. Catalyzing Innovation. Global Health and the Future Role of the United States. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2017.

Akenroye T. Factors influencing innovation in healthcare: a conceptual synthesis. Innov J. 2012;17(2):1.

Varkey P, Horne A, Bennet KE. Innovation in health care: a primer. Am J Med Qual. 2008;23(5):382–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860608317695.

Mulgan G, Albury D. Innovation in the public sector. Strategy Unit Cabinet Office. 2003;1(1):40.

Gary H. Leading the revolution by Gary Hamel. Harvard Business School Press; 2001.

Clayton M, Christensen SD, Anthony EA, Roth RK. Seeing what’s next: using the theories of innovation to predict industry change. n: Wiley Online Library; 2007.

Hadzimustafa S, Rexhepi G. Measuring innovation in the 21st century economy. SSRN Electron J. 2011. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1929039.

Länsisalmi H, Kivimäki M, Aalto P, Ruoranen R. Innovation in healthcare: a systematic review of recent research. Nurs Sci Q. 2006;19(1):66–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894318405284129. (discussion 65).

Moore GA. Darwin and the demon: innovating within established enterprises. Harv Bus Rev. 2004;82(7–8):86–92 (187).

de Solà-Morales O, Cunningham D, Flume M, Overton PM, Shalet N, Capri S. Defining innovation with respect to new medicines: a systematic review from a payer perspective. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2018;34(3):224–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266462318000259.

Shiroiwa T, Fukuda T, Ikeda S, Takura T. New decision-making processes for the pricing of health technologies in Japan: The FY 2016/2017 pilot phase for the introduction of economic evaluations. Health Policy. 2017;121(8):836–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.06.001.

Kimble L, Massoud MR. What do we mean by innovation in healthcare? EMJ reviews 2016 [cited 2021 21 August]; https://www.emjreviews.com/innovations/article/what-do-we-mean-by-innovation-in-healthcare/. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;21(339):b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535.

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938.

Fineout-Overholt E, Johnston L. Teaching EBP: asking searchable, answerable clinical questions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2005;2(3):157–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2005.00032.x.

Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2007;15(7):16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-7-16.

Munos B. A forensic analysis of drug targets from 2000 through 2012. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94(3):407–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2013.126.

Lanthier M, Miller KL, Nardinelli C, Woodcock J. An improved approach to measuring drug innovation finds steady rates of first-in-class pharmaceuticals, 1987–2011. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(8):1433–9. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0541.

Battaglia LE. Drug Reformulation Regulatory Gaming: Enforcement and Innovation Implications. Euro Compet J. 2011;7(2):379–405. https://doi.org/10.5235/174410511797248315.

Yin N. Pharmaceuticals, Incremental Innovation and Market Exclusivity. Toulouse School of Economics, Job Market Paper; May 12, 2013. P. 62.

Hult KJ. Incremental innovation and pharmaceutical productivity. 2015 [cited 2021 21 August ]; https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/How-Does-Technological-Change-Affect-Quality-Adjusted-Prices-1.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

Sternitzke C. Knowledge sources, patent protection, and commercialization of pharmaceutical innovations. Res Policy. 2010;39(6):810–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.03.001.

Huber M, Huber B. Innovation in Oncology Drug Development. J Oncol. 2019;2019:9683016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9683016.

Morgan SG, Cunningham CM, Law MR. Drug development: innovation or imitation deficit? BMJ. 2012;345:e5880. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e5880.

Gonzalez SSHJ. FDA’s “Breakthrough“ Drug Therapy Designation. Pharmind. 2015;77(6):801–8.

Kennedy I. Appraising the value of innovation and other benefits: a short study for NICE. 2009 [cited 2021 21 August]; https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/Research-and-development/Kennedy-study-final-report.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

Linley WG, Hughes DA. Societal views on NICE, cancer drugs fund and value-based pricing criteria for prioritising medicines: a cross-sectional survey of 4118 adults in Great Britain. Health Econ. 2013;22(8):948–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.2872.

Warren-Jones A. Regulatory theory: commercially sustainable markets rely upon satisfying the public interest in obtaining credible goods. Health Econ Policy Law. 2017;12(4):471–93. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1744133117000123.

Ferner RE, Hughes DA, Aronson JK. NICE and new: appraising innovation. BMJ. 2010 Jan 5;340:b5493. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b5493.

Green C. Considering the value associated with innovation in health technology appraisal decisions (deliberations): a NICE thing to do? Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2010;8(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03256161.

Bryan S, Lee H, Mitton C. “Innovation” in health care coverage decisions: all talk and no substance? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013;18(1):57–60. https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2012.012031.

Rawlins M, Barnett D, Stevens A. Pharmacoeconomics: NICE’s approach to decision-making. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70(3):346–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03589.x.

Ward DJ, Slade A, Genus T, Martino OI, Stevens AJ. How innovative are new drugs launched in the UK? A retrospective study of new drugs listed in the British National Formulary (BNF) 2001–2012. BMJ Open. 2014;4(10):e006235. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006235.

Dervaux B, Le Fur C, Dubois S, Josseran A. What is the budget impact of a new treatment or new health technology arriving on the market? Therapie. 2017;72(1):93–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.therap.2016.12.003.

Andrade LF, Sermet C, Pichetti S. Entry time effects and follow-on drug competition. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17(1):45–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-014-0654-9.

Gridchyna I, Aulois-Griot M, Maurain C, Bégaud B. How innovative are pharmaceutical innovations? The case of medicines financed through add-on payments outside of the French DRG-based hospital payment system. Health Policy. 2012;104(1):69–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.11.007.

Bennette CS, Basu A, Ramsey SD, Helms Z, Bach PB. Returns to Pharmaceutical Innovation in the Market for Oral Chemotherapy in Response to Insurance Coverage Expansion. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc, NBER Working Papers. 2017.

Planel M-P. Chapter 1. The challenges of pricing innovative drugs. J Int Bioethique Ethique Sci. 2018;29(2):15–33. https://doi.org/10.3917/jibes.292.0015.

Lario IP. The iris project on ibodutant: clinical development of a new, first-in-class innovative agent for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). In: Basic and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology, 27th Congress of the Spanish Society for Clinical Pharmacology; 2014.

Bennette CS, Basu A, Ramsey SD, Helms Z, Bach PB. Health Returns to pharmaceutical innovation in the market for oral chemotherapy in response to insurance coverage expansion. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc NBER Working Papers Vol 5 (3) p 360-75 2019 [cited 2021 21 August]; https://doi.org/10.1162/ajhe_a_00125?journalCode=ajhe.

Smith A, Shu A, Jensen S, Sprogøe K. PDG9 transcon technology: solving unmet need. Validation in pediatric growth hormone deficiency. Value in Health ISPOR2019. 22(3):S598.

Roberts G. Value based pricing: One threshold too far for the United Kingdom. ISPOR 14th Annual European Congress; 2011; Madrid Spain. p. A241.

Quinn C, Palmer S, Bruns J, Borrás JM, Grant C, Sykes D, et al. Innovation in oncology: Why focusing only on breakthrough innovation may be counter-productive. Haematologica. 2015;100:774.

Iordatii M, Venot A, Duclos C. Designing concept maps for a precise and objective description of pharmaceutical innovations. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;18(13):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-13-10.

Gonçalves A, Maraninchi D, Marino P. Anticancer drugs: Which prices for therapeutic innovations? Bull Cancer. 2016;103(4):361–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bulcan.2016.03.002.

Cadranel JPC, Vieira T, Ruppert A-M, Gounant V, Lavolé A, Wislez M. How can we offer everyone access to innovative therapeutics? J Respir Dis News. 2015;7(4):462–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1877-1203(16)30030-1.

Gandjour A. Underuse of innovative medicines in Germany: A justification for government intervention? Health Policy. 2018;122(12):1283–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.08.009.

Pokrivka J, Franken C, Haas B, Eckstein N. Early benefit assessment of innovative drugs: outcomes of the initially concluded procedures. Deutsche Apotheker-Zeitung. 2012;152:44–9.

Hatanaka Y. Toward bringing innovation in drug discovery to the world. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22 Suppl 2:9-2.

Griffiths P, Quigley E, Vandam L, Mounteney J. The challenge of responding to a more globally joined-up, dynamic, and innovative drug market: Reflections from the EMCDDA´s 2018 analysis of the European drug situation. Dusunen Adam. 2018;31:231–7. https://doi.org/10.5350/DAJPN20183103001.

Rolón MJ, Figueroa MI, Sued O, Cahn P. Lopinavir/ritonavir in new initial antiretroviral treatment strategies. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2014;32(Suppl 3):7–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0213-005x(14)70161-2.

Goldman DP, Lakdawalla DN, Malkin JD, Romley J, Philipson T. The benefits from giving makers of conventional “small molecule” drugs longer exclusivity over clinical trial data. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(1):84–90. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1056.

Grabowski H. the evolution of the pharmaceutical industry over the past 50 years: a personal reflection. Int J Econ Bus. 2011;18(2):161–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/13571516.2011.584421.

Tripathy S, Prajapati V, Guruswamy VKS. product life cycle management for pharmaceutical innovation. Appl Clin Research, Clin Trials Regul Affairs. 2015;2(3):145–52.

Kyle MK. Are important innovations rewarded? Evidence from pharmaceutical markets. Rev Ind Org. 2018;53(1):211–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-018-9639-7.

Tomas MC, Peng B. A cheat sheet to navigate the complex maze of pharmaceutical exclusivities in Europe. Pharm Pat Anal. 2017;6(4):161–70. https://doi.org/10.4155/ppa-2017-0010.

Kesselheim AS. An empirical review of major legislation affecting drug development: past experiences, effects, and unintended consequences. Milbank Q. 2011;89(3):450–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00636.x.

Gaudry KS. Exclusivity strategies and opportunities in view of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act. Food aDrug Law J. 2011;66(4):587–630 (ii).

Prajapati V, Tripathy S, Dureja H. Product lifecycle management through patents and regulatory strategies. Food and Drug Law Journal. 2013;13(3):171–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745790413497388.

Branstetter L, Chatterjee C, Higgins MJ. Regulation and welfare: evidence from paragraph IV generic entry in the pharmaceutical industry. Rand J Econ. 2016;47(4):857–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-2171.12157.

Gorry P, Useche D. Orphan Drug Designations as Valuable Intangible Assets for IPO Investors in Pharma- Biotech Companies. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc, NBER Working Paper Series. Working Paper 24021. 2017. http://www.nber.org/papers/w24021. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

Hwang TJ, Bourgeois FT. New regulatory paradigms for innovative drugs to treat pediatric diseases. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(10):879–80. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.904.

Alexander GC, O’Connor AB, Stafford RS. Enhancing prescription drug innovation and adoption. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(12):833–7. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-154-12-201106210-00012. (w-301).

Iizuka T, Uchida G. Promoting innovation in small markets: Evidence from the market for rare and intractable diseases. J Health Econ. 2017;54:56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.03.006.

Natz A, Campion M-G. Pricing and reimbursement of innovative pharmaceuticals in France and the new healthcare reform. Farmecon Health Econ ther Pathw. 2012;13(2):49–60. https://doi.org/10.7175/fe.v13i2.270.

Hughes DA. Value-based pricing: incentive for innovation or zero net benefit? Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(9):731–5. https://doi.org/10.2165/11592570-000000000-00000.

Scherpereel A, Durand-Zaleski I, Cotté FE, Fernandes J, Debieuvre D, Blein C, et al. Access to innovative drugs for metastatic lung cancer treatment in a French nationwide cohort: the TERRITOIRE study. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):1013. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4958-5.

Cadranel J, Créquit P, Vieira T, Ruppert A-M, Gounant V, Lavolé A, et al. How can we offer everyone access to innovative therapeutics? J Respir Dis News. 2015;7(4):462–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1877-1203(16)30030-1.

Rial-Sebbag E, Chabannon C. Chapter 6. Legal issues and for the health system of the development of a new class of innovative therapy in oncoimmunology: the “Car-T CellS". J Int Bioethique Ethique Sci. 2018;29(2):113–28. https://doi.org/10.3917/jibes.292.0113.

Årdal C, Baraldi E, Theuretzbacher U, Outterson K, Plahte J, Ciabuschi F, et al. Insights into early stage of antibiotic development in small- and medium-sized enterprises: a survey of targets, costs, and durations. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2018;11:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-018-0135-0.

Årdal C, Lacotte Y, Ploy MC. Financing pull mechanisms for antibiotic-related innovation: opportunities for Europe. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(8):1994–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa153.

Recommendations for Horizon Scanning, Topic Identification, Selection and Prioritisation for European Cooperation on Health Technology Assessment. 2020 [cited 2021 21 August]; https://eunethta.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/200305-EUnetHTA-WP4-Deliverable-4.10-TISP-recommendations-final-version-1.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

World Health Organization. Regional Office for E, European Observatory on Health S, Policies, Nolte E. How do we ensure that innovation in health service delivery and organization is implemented, sustained and spread? 2018 [cited 2021 August]; https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/380731/pb-tallinn-03-eng.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

WHO Health Innovation Group. [cited 2021 21 August]; https://www.who.int/phi/1-health_innovation-brochure.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

2013 Policy Forum: HTA and Value: Assessing value, making value-based decisions, and sustaining innovation. 2013 [cited 2021 21 August]; https://htai.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/HTAi_Policy_Forum_Background_Paper_2013.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

Haute Autorité de Santé. Methods for Health Economic Evaluation. Web page posted on 27 Oct 2015. https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_2035665/en/methods-for-health-economic-evaluation

Single technology appraisal: User guide for company evidence submission template. 2015 [cited 2021 21 August]; https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg24/resources/single-technology-appraisal-user-guide-for-company-evidence-submission-template-pdf-72286715419333. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

Innovation into action supporting delivery of the NHS Five Year Forward View. 2015 [cited 2021 21 August]; https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/nhs-inovation-into-action.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

Facing the dynamics of future innovation: The role of HTA, industry and health system in scanning the horizon. 2018 [cited 2021 21 August]; https://htai.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/HTAi_Global_Policy_Forum_2018_Background_Paper.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

Health Care Horizon Scanning System- A Systematic Review of Methods for Health Care Technology Horizon Scanning. 2013 [cited 2021 21 August]; https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/horizon-scan_research-2013.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

Oortwijn W, on behalf of the HTAi Global Policy Forum. Background Paper for the HTAi 2017 Policy Forum – “From Theory To Action: Developments In Value Frameworks To Inform The Allocation of Health Care Resources”. December 2016. https://past.htai.org/wpcontent/uploads/2018/02/HTAi_Policy_Forum_2017_Background_Paper.pdf

Central Social Insurance Medical Council MJ. Outline of Drastic Reform of the Drug Pricing System (draft). 2017 [cited 2021 29 June]; https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-12404000-Hokenkyoku-Iryouka/0000188705.pdf. Accessed 29 Jun 2021.

MHLW. Overview of drastic reform of the drug pricing system in fiscal 2018. 2018 [cited 2021 29 June]; https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-12400000-Hokenkyoku/0000114381_2.pdf. Accessed 29 Jun 2021.

MHLW. Documents Submitted by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. [cited 2021 29 June]; https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10807000/000567934.pdf. Accessed 29 Jun 2021.

MHLW. Promotion of Practical Application of Innovative Drugs, Medical Devices and Regenerative Medicine Products. Health and medical care 2012 [cited 2021 21 August]; https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/iyakuhin/kakushin/index.html. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

Kenichi T. CiNii Goverment policies for creation of world-leading innovative new drugs from Japan. Drug Deliv. 2011;26(2):126–34.

Tahara S, Kobayashi N, Baimi S, Ito S, Nakahara Y, Morimoto T, et al. CiNii Of the academic and venture drug discovery seeds. Open Innov Drug Discov. 2014;143:198–202.

Mimura Y. Public pricing policy and trade practices in pharmaceutical distribution: A research group report on pharmaceutical distribution. Acade Stud J Health Care Soc. 2011;21(2):137–162.

Ushirozawa N. Current situation and challenge in clinical trial activation. J Natl Inst Public Health. 2011;60(1):3–7.

IHEP. National strategic special zones and healthcare system reform. Med Econ Res. 2015;27(2):85–99 (cited 2021 21 August).

IHEP. Survey and Research on Drug Use. March 2011 [cited 2021 21 Agust]; https://www.ihep.jp/wp-content/uploads/current/report/study/204/10203ab.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

IHEP. Survey and research on drug use. 2019 Mar [cited 2021 21 August]; https://www.ihep.jp/wp-content/uploads/current/report/study/465/18201ab.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

Tawara SKK, Arai H, Masumi S, Itoh S, Nakahara Y, et al. Requirements for the linsence-out of drug candidates to pharmaceutical companies. Folia Pharmacol Jpn. 2014;143:198–202.

Ye M. Essays in Industrial Organization: Market Performance. 2012 [cited 2021 August]; https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/31985. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

Kennedy DC. Strange bedfellows: native american tribes, big pharma, and the legitimacy of their alliance. Duke Law J. 2019;68(7):1433–68.

Ross CD, Armen B, Benjamin Y, Kevin K. The global biomedical industry preserving U.S. Leadership. Berlin: Milken Institute; 2011.

Wamble DE, Ciarametaro M, Dubois R. The effect of medical technology innovations on patient outcomes, 1990–2015: results of a physician survey. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(1):66–71. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2018.18083.

Carranza Rosenzweig J, Cieply B. PNS122 Overview of health economic assessments for innovative treatments in US and UK. Value Health. 2020;23:S306–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2020.04.1125.

Drummond M, Towse A. Is rate of return pricing a useful approach when value-based pricing is not appropriate? Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20(7):945–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-019-01032-7.

Hess LM, Brnabic A, Mason O, Lee P, Barker S. Relationship between progression-free survival and overall survival in randomized clinical trials of targeted and biologic agents in oncology. J Cancer. 2019;10(16):3717–27. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.32205.

Knight-Schrijver VR, Chelliah V, Cucurull-Sanchez L, Le Novere N. The promises of quantitative systems pharmacology modelling for drug development. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2016;14:363–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2016.09.002.

Liu X, Thomas CE, Felder CC. The impact of external innovation on new drug approvals: a retrospective analysis. Int J Pharm. 2019;30(563):273–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.12.093.

Milward D, Bjareland M, Hayes W, Maxwell M, Oberg L, Tilford N, et al. Ontology-based interactive information extraction from scientific abstracts. Comp Funct Genom. 2005;6(1–2):67–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/cfg.456.

Solomon MD, Tabada G, Allen A, Sung SH, Go AS. Abstract 12926: using natural language processing to accurately identify aortic stenosis in a large, integrated healthcare delivery system. Circulation. 2019;140(Suppl_1):A12926-A. https://doi.org/10.1161/circ.140.suppl_1.12926.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Mercè Conill-Cortés (Linguamatics, an IQVIA company) for contributing to the data analyses. We thank Ruchi Singhal, Ashish Verma, Himanshi Yadav, Udaya Lakkakula, Aditya Kumar Kataria, and Richa Goyal (IQVIA) for conducting the literature review. Each of these members is specially trained in the literature review process. We also thank Todd D. Taylor, Rosario Vivek, Paranjoy Saharia, Kiran Chaudhary, and Akshata Patil (IQVIA) for manuscript writing (including drafting, revising, and formatting) and editorial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Pfizer Japan Inc. was the only direct sponsor of this study and fees were paid to IQVIA Solutions Japan K.K.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

Naohiko Wakutsu received an advisory fee from Pfizer Japan Inc. Emi Hirose and Naohiro Yonemoto are full-time employees of Pfizer Japan Inc. and stockholders in Pfizer Inc. Sven Demiya is a full-time employee of IQVIA Solutions Japan K.K. This SLR used I2E Enterprise software from Linguamatics, which is a proprietary Natural Language Processing (NLP) software.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used for the review was gathered from various database domains of agencies and hence is publicly available; it is also available from the corresponding author upon submission of a reasonable request.

Code availability

Initial content was derived using the I2E Enterprise software from Linguamatics (www.linguamatics.com; UK), and no additional software code was developed. Additional information can be provided upon submission of a reasonable request.

Ethics approval

The study does not involve human participants; no ethical approval is required.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work, and have given final approval for this version of the manuscript to be published. All named authors contributed to the study design, data extraction, and reviewing of the manuscript. None of the authors were involved in the literature searching process.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wakutsu, N., Hirose, E., Yonemoto, N. et al. Assessing Definitions and Incentives Adopted for Innovation for Pharmaceutical Products in Five High-Income Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Pharm Med 37, 53–70 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40290-022-00457-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40290-022-00457-5