Abstract

Background

As the number and type of cancer treatments available rises and patients live with the consequences of their disease and treatments for longer, understanding preferences for cancer care can help inform decisions about optimal treatment development, access, and care provision. Discrete choice experiments (DCEs) are commonly used as a tool to elicit stakeholder preferences; however, their implementation in oncology may be challenging if burdensome trade-offs (e.g. length of life versus quality of life) are involved and/or target populations are small.

Objectives

The aim of this review was to characterise DCEs relating to cancer treatments that were conducted between 1990 and March 2020.

Data Sources

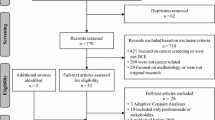

EMBASE, MEDLINE, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were searched for relevant studies.

Study Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they implemented a DCE and reported outcomes of interest (i.e. quantitative outputs on participants’ preferences for cancer treatments), but were excluded if they were not focused on pharmacological, radiological or surgical treatments (e.g. cancer screening or counselling services), were non-English, or were a secondary analysis of an included study.

Analysis Methods

Analysis followed a narrative synthesis, and quantitative data were summarised using descriptive statistics, including rankings of attribute importance.

Result

Seventy-nine studies were included in the review. The number of published DCEs relating to oncology grew over the review period. Studies were conducted in a range of indications (n = 19), most commonly breast (n =10, 13%) and prostate (n = 9, 11%) cancer, and most studies elicited preferences of patients (n = 59, 75%). Across reviewed studies, survival attributes were commonly ranked as most important, with overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) ranked most important in 58% and 28% of models, respectively. Preferences varied between stakeholder groups, with patients and clinicians placing greater importance on survival outcomes, and general population samples valuing health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Despite the emphasis of guidelines on the importance of using qualitative research to inform attribute selection and DCE designs, reporting on instrument development was mixed.

Limitations

No formal assessment of bias was conducted, with the scope of the paper instead providing a descriptive characterisation. The review only included DCEs relating to cancer treatments, and no insight is provided into other health technologies such as cancer screening. Only DCEs were included.

Conclusions and Implications

Although there was variation in attribute importance between responder types, survival attributes were consistently ranked as important by both patients and clinicians. Observed challenges included the risk of attribute dominance for survival outcomes, limited sample sizes in some indications, and a lack of reporting about instrument development processes.

Protocol Registration

PROSPERO 2020 CRD42020184232.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration, Fitzmaurice C, Abate D, Abbasi N, Abbastabar H, Abd-Allah F, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 29 cancer groups, 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(12):1749–68. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2996.

Harris RE. Epidemiology of chronic disease: global perspectives. Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2019.

Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, Harewood R, Matz M, Niksic M, et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000–14 (concord-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1023–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33326-3.

National Cancer Institute. Cancer trends progress report. 2020. https://progressreport.cancer.gov. Accessed 6 Aug 2020.

Salas-Vega S, Iliopoulos O, Mossialos E. Assessment of overall survival, quality of life, and safety benefits associated with new cancer medicines. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(3):382–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4166.

Haslam A, Herrera-Perez D, Gill J, Prasad V. Patient experience captured by quality-of-life measurement in oncology clinical trials. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e200363. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0363.

Mierzynska J, Piccinin C, Pe M, Martinelli F, Gotay C, Coens C, et al. Prognostic value of patient-reported outcomes from international randomised clinical trials on cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(12):e685–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30656-4.

Pharma Intelligence. Pharmaprojects, a drug development database. Informa PLC. 2020. https://pharmaintelligence.informa.com/products-and-services/data-and-analysis/pharmaprojects. Accessed 30 Nov 2020.

Bouvy JC, Cowie L, Lovett R, Morrison D, Livingstone H, Crabb N. Use of patient preference studies in hta decision making: a nice perspective. Patient. 2020;13(2):145–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-019-00408-4.

US FDA. Patient preference information—voluntary submission, review in premarket approval applications, humanitarian device exemption applications, and de novo requests, and inclusion in decision summaries and device labeling. 2016. https://www.fda.gov/media/92593/download. Accessed 6 Aug 2020.

Marsh K, van Til JA, Molsen-David E, Juhnke C, Hawken N, Oehrlein EM, et al. Health preference research in Europe: a review of its use in marketing authorization, reimbursement, and pricing decisions-report of the ISPOR stated preference research special interest group. Value Health. 2020;23(7):831–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2019.11.009.

Postmus D, Mavris M, Hillege HL, Salmonson T, Ryll B, Plate A, et al. Incorporating patient preferences into drug development and regulatory decision making: results from a quantitative pilot study with cancer patients, carers, and regulators. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99(5):548–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.332.

Mockford C, Staniszewska S, Griffiths F, Herron-Marx S. The impact of patient and public involvement on UK NHS health care: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(1):28–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzr066.

Johnson FR, Zhou M. Patient preferences in regulatory benefit-risk assessments: a US perspective. Value Health. 2016;19(6):741–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.008.

Vass CM, Payne K. Using discrete choice experiments to inform the benefit-risk assessment of medicines: are we ready yet? Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(9):859–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-017-0518-0.

Huls SPI, Whichello CL, van Exel J, Uyl-de Groot CA, de Bekker-Grob EW. What is next for patient preferences in health technology assessment? A systematic review of the challenges. Value Health. 2019;22(11):1318–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2019.04.1930.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2020 abridged for primary care providers. Clin Diabetes. 2020;38(1):10.

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention (2020 update). 2020. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/GINA-2020-report_20_06_04-1-wms.pdf. Accessed Mar 2021.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Inc. Pocket guide to COPD: Diagnosis, management, and prevention. 2020. Available at: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/GOLD-2020-POCKET-GUIDE-ver1.0_FINAL-WMV.pdf. Accessed Mar 2021.

Mahieu PA, Andersson H, Beaumais O, dit Sourd RC, Hess S, Wolff F. Stated preferences: a unique database composed of 1657 recent published articles in journals related to agriculture, environment or health. Rev Agric Food Environ Stud. 2017;98(3):201–20.

de Bekker-Grob EW, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ. 2012;21(2):145–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1697.

Clark MD, Determann D, Petrou S, Moro D, de Bekker-Grob EW. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(9):883–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0170-x.

Ryan M, Gerard K. Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: current practice and future research reflections. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2003;2(1):55–64.

Soekhai V, de Bekker-Grob EW, Ellis AR, Vass CM. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: past, present and future. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(2):201–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0734-2.

Shrestha A, Martin C, Burton M, Walters S, Collins K, Wyld L. Quality of life versus length of life considerations in cancer patients: a systematic literature review. Psychooncology. 2019;28(7):1367–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5054.

Laryionava K, Sklenarova H, Heussner P, Haun MW, Stiggelbout AM, Hartmann M, et al. Cancer patients’ preferences for quantity or quality of life: German translation and validation of the quality and quantity questionnaire. Oncol Res Treat. 2014;37(9):472–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000366250.

Guerra RL, Castaneda L, de Albuquerque RCR, Ferreira CBT, Correa FM, Fernandes RRA, et al. Patient preferences for breast cancer treatment interventions: a systematic review of discrete choice experiments. Patient. 2019;12(6):559–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-019-00375-w.

Mansfield C, Tangka FK, Ekwueme DU, Smith JL, Guy GP Jr, Li C, et al. Stated preference for cancer screening: a systematic review of the literature, 1990–2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E27. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd13.150433.

Damm K, Vogel A, Prenzler A. Preferences of colorectal cancer patients for treatment and decision-making: a systematic literature review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2014;23(6):762–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12207.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the prisma statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Collacott H, Heidenreich S, Brooks A, Soekhai V, Brookes E, Thomas C et al. Discrete choice experiments in oncology: a systematic review. PROSPERO 2020 CRD42020184232. 2020. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020184232. Accessed 30 Nov 2020.

Coast J, Al-Janabi H, Sutton EJ, Horrocks SA, Vosper AJ, Swancutt DR, et al. Using qualitative methods for attribute development for discrete choice experiments: issues and recommendations. Health Econ. 2012;21(6):730–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1739.

Vass C, Rigby D, Payne K. The role of qualitative research methods in discrete choice experiments. Med Decis Mak. 2017;37(3):298–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X16683934.

Coast J, Horrocks S. Developing attributes and levels for discrete choice experiments using qualitative methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007;12(1):25–30. https://doi.org/10.1258/135581907779497602.

Kløjgaard ME, Bech M, Søgaard R. Designing a stated choice experiment: the value of a qualitative process. J Choice Model. 2012;5(2):1–18.

Bolt T, Mahlich J, Nakamura Y, Nakayama M. Hematologists’ preferences for first-line therapy characteristics for multiple myeloma in Japan: attribute rating and discrete choice experiment. Clin Ther. 2018;40(2):296-308.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.12.012.

Boque C, Abad MR, Agustin MJ, Garcia-Goni M, Moreno C, Gabas-Rivera C, et al. Treatment decision-making in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: key factors for healthcare professionals. PRELIC study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(1):24–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2019.03.010.

Bridges JF, la Cruz M, Pavilack M, Flood E, Janssen EM, Chehab N, et al. Patient preferences for attributes of tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatments for EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. Future Oncol. 2019;15(34):3895–907. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2019-0396.

Brockelmann PJ, McMullen S, Wilson JB, Mueller K, Goring S, Stamatoullas A, et al. Patient and physician preferences for first-line treatment of classical hodgkin lymphoma in Germany, France and the UK. Br J Haematol. 2019;184(2):202–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.15566.

De Abreu LR, Haas M, Hall J, Parish K, Stuart D, Viney R. My mind is made up: cancer concern and women’s preferences for contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2019;28(4):e13058. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13058.

de Freitas HM, Ito T, Hadi M, Al-Jassar G, Henry-Szatkowski M, Nafees B, et al. Patient preferences for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer treatments: a discrete choice experiment among men in three European countries. Adv Ther. 2019;36(2):318–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0861-3.

Gonzalez JM, Doan J, Gebben DJ, Boeri M, Fishman M. Comparing the relative importance of attributes of metastatic renal cell carcinoma treatments to patients and physicians in the United States: a discrete-choice experiment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(8):973–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0640-7.

Havrilesky LJ, Lim S, Ehrisman JA, Lorenzo A, Alvarez Secord A, Yang JC, et al. Patient preferences for maintenance parp inhibitor therapy in ovarian cancer treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;156(3):561–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.01.026.

Havrilesky LJ, Yang JC, Lee PS, Secord AA, Ehrisman JA, Davidson B, et al. Patient preferences for attributes of primary surgical debulking versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy for treatment of newly diagnosed ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2019;125(24):4399–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32447.

Ivanova J, Hess LM, Garcia-Horton V, Graham S, Liu X, Zhu Y, et al. Patient and oncologist preferences for the treatment of adults with advanced soft tissue sarcoma: a discrete choice experiment. Patient. 2019;12(4):393–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-019-00355-0.

Liu FX, Witt EA, Ebbinghaus S, DiBonaventura BG, Basurto E, Joseph RW. Patient and oncology nurse preferences for the treatment options in advanced melanoma: a discrete choice experiment. Cancer Nurs. 2019;42(1):E52–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000557.

MacEwan JP, Doctor J, Mulligan K, May SG, Batt K, Zacker C, et al. The value of progression-free survival in metastatic breast cancer: results from a survey of patients and providers. MDM Policy Pract. 2019;4(1):2381468319855386. https://doi.org/10.1177/2381468319855386.

Mansfield C, Ndife B, Chen J, Gallaher K, Ghate S. Patient preferences for treatment of metastatic melanoma. Future Oncol. 2019;15(11):1255–68. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2018-0871.

McMullen S, Hess LM, Kim ES, Levy B, Mohamed M, Waterhouse D, et al. Treatment decisions for advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer: patient and physician perspectives on maintenance therapy. Patient. 2019;12(2):223–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-018-0327-3.

Muhlbacher AC, Juhnke C. Patient preferences concerning alternative treatments for neuroendocrine tumors: results of the “PIANO-study.” Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2019;35(3):243–51. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462319000217.

Nakayama M, Kobayashi H, Okazaki M, Imanaka K, Yoshizawa K, Mahlich J. Patient preferences and urologist judgments on prostate cancer therapy in Japan. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12(4):1094–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988318776123.

Nickel B, Howard K, Brito JP, Barratt A, Moynihan R, McCaffery K. Association of preferences for papillary thyroid cancer treatment with disease terminology: a discrete choice experiment. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(10):887–96. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2018.1694.

Noordman BJ, de Bekker-Grob EW, Coene P, van der Harst E, Lagarde SM, Shapiro J, et al. Patients’ preferences for treatment after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 2018;105(12):1630–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10897.

Norman R, Anstey M, Hasani A, Li I, Robinson S. What matters to potential patients in chemotherapy service delivery? A discrete choice experiment. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020;18(4):589–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-020-00555-y.

Omori Y, Enatsu S, Cai Z, Ishiguro H. Patients’ preferences for postmenopausal hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced breast cancer treatments in Japan. Breast Cancer. 2019;26(5):652–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-019-00965-4.

Pauwels K, Huys I, Casteels M, Denier Y, Vandebroek M, Simoens S. What does society value about cancer medicines? A discrete choice experiment in the Belgian population. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2019;17(6):895–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-019-00504-4.

Phillips CM, Deal K, Powis M, Singh S, Dharmakulaseelan L, Naik H, et al. Evaluating patients’ perception of the risk of acute care visits during systemic therapy for cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(7):e622–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.19.00551.

Qian Y, Arellano J, Gatta F, Hechmati G, Hauber AB, Mohamed AF, et al. Physicians’ preferences for bone metastases treatments in France, Germany and the United Kingdom. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):518. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3272-x.

Rosato R, Di Cuonzo D, Ritorto G, Fanchini L, Bustreo S, Racca P, et al. Tailoring chemotherapy supply according to patients’ preferences: a quantitative method in colorectal cancer care. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(1):73–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2019.1670475.

Salampessy BH, Bijlsma WR, van der Hijden E, Koolman X, Portrait FRM. On selecting quality indicators: preferences of patients with breast and colon cancers regarding hospital quality indicators. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(7):576–85. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009818.

Seo J, Smith BD, Estey E, Voyard E, O’Donoghue B, Bridges JFP. Developing an instrument to assess patient preferences for benefits and risks of treating acute myeloid leukemia to promote patient-focused drug development. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(12):2031–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2018.1456414.

Spaich S, Kinder J, Hetjens S, Fuxius S, Gerhardt A, Sutterlin M. Patient preferences regarding chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer—a conjoint analysis for common taxanes. Front Oncol. 2018;8:535. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2018.00535.

Stein EM, Yang M, Guerin A, Gao W, Galebach P, Xiang CQ, et al. Assessing utility values for treatment-related health states of acute myeloid leukemia in the United States. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):193. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-1013-9.

Stellato D, Thabane M, Eichten C, Delea TE. Preferences of Canadian patients and physicians for adjuvant treatments for melanoma. Curr Oncol. 2019;26(6):e755–65. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.26.5085.

Stenehjem DD, Au TH, Ngorsuraches S, Ma J, Bauer H, Wanishayakorn T, et al. Immunotargeted therapy in melanoma: patient, provider preferences, and willingness to pay at an academic cancer center. Melanoma Res. 2019;29(6):626–34. https://doi.org/10.1097/CMR.0000000000000572.

Storm-Dickerson T, Das L, Gabriel A, Gitlin M, Farias J, Macarios D. What drives patient choice: preferences for approaches to surgical treatments for breast cancer beyond traditional clinical benchmarks. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6(4):e1746. https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000001746.

Sun H, Wang H, Shi L, Wang M, Li J, Shi J, et al. Physician preferences for chemotherapy in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer in china: evidence from multicentre discrete choice experiments. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e032336. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032336.

Sun H, Wang H, Xu N, Li J, Shi J, Zhou N, et al. Patient preferences for chemotherapy in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: a multicenter discrete choice experiment (DCE) study in china. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:1701–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S224529.

Valenti V, Ramos J, Perez C, Capdevila L, Ruiz I, Tikhomirova L, et al. Increased survival time or better quality of life? Trade-off between benefits and adverse events in the systemic treatment of cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22(6):935–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-019-02216-6.

Vallejo-Torres L, Melnychuk M, Vindrola-Padros C, Aitchison M, Clarke CS, Fulop NJ, et al. Discrete-choice experiment to analyse preferences for centralizing specialist cancer surgery services. Br J Surg. 2018;105(5):587–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10761.

Watson V, McCartan N, Krucien N, Abu V, Ikenwilo D, Emberton M, et al. Evaluating the trade-offs men with localized prostate cancer make between the risks and benefits of treatments: the compare study. J Urol. 2020;204(2):273–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000000754.

Weilandt J, Diehl K, Schaarschmidt ML, Kieker F, Sasama B, Pronk M, et al. Patient preferences in adjuvant and palliative treatment of advanced melanoma: a discrete choice experiment. Acta Dermatovenereol. 2020;100(6):adv00083. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-3422.

Wilke T, Mueller S, Bauer S, Pitura S, Probst L, Ratsch BA, et al. Treatment of relapsed refractory multiple myeloma: which new PI-based combination treatments do patients prefer? Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:2387–96. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S183187.

Benjamin L, Cotte FE, Philippe C, Mercier F, Bachelot T, Vidal-Trecan G. Physicians’ preferences for prescribing oral and intravenous anticancer drugs: a discrete choice experiment. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(6):912–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2011.09.019.

Mohamed AF, Gonzalez JM, Fairchild A. Patient benefit-risk tradeoffs for radioactive iodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer treatments. J Thyroid Res. 2015;2015:438235. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/438235.

Muhlbacher AC, Nubling M. Analysis of physicians’ perspectives versus patients’ preferences: direct assessment and discrete choice experiments in the therapy of multiple myeloma. Eur J Health Econ. 2011;12(3):193–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-010-0218-6.

Regier DA, Diorio C, Ethier MC, Alli A, Alexander S, Boydell KM, et al. Discrete choice experiment to evaluate factors that influence preferences for antibiotic prophylaxis in pediatric oncology. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47470. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047470.

Essers BA, Dirksen CD, Prins MH, Neumann HA. Assessing the public’s preference for surgical treatment of primary basal cell carcinoma: a discrete-choice experiment in the south of the Netherlands. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36(12):1950–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01805.x.

Qian Y, Arellano J, Hauber AB, Mohamed AF, Gonzalez JM, Hechmati G, et al. Patient, caregiver, and nurse preferences for treatments for bone metastases from solid tumors. Patient. 2016;9(4):323–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-015-0158-4.

Meghani SH, Chittams J, Hanlon AL, Curry J. Measuring preferences for analgesic treatment for cancer pain: how do African–Americans and whites perform on choice-based conjoint (CBC) analysis experiments? BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13:118. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-13-118.

Arellano J, Gonzalez JM, Qian Y, Habib M, Mohamed AF, Gatta F, et al. Physician preferences for bone metastasis drug therapy in canada. Curr Oncol. 2015;22(5):e342-348. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.22.2380.

Thrumurthy SG, Morris JJ, Mughal MM, Ward JB. Discrete-choice preference comparison between patients and doctors for the surgical management of oesophagogastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2011;98(8):1124–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.7537 (discussion 1132).

Salkeld G, Solomon M, Butow P, Short L. Discrete-choice experiment to measure patient preferences for the surgical management of colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92(6):742–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.4917.

Hauber AB, Arellano J, Qian Y, Gonzalez JM, Posner JD, Mohamed AF, et al. Patient preferences for treatments to delay bone metastases. Prostate. 2014;74(15):1488–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.22865.

Essers BA, van Helvoort-Postulart D, Prins MH, Neumann M, Dirksen CD. Does the inclusion of a cost attribute result in different preferences for the surgical treatment of primary basal cell carcinoma? A comparison of two discrete-choice experiments. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(6):507–20. https://doi.org/10.2165/11532240-000000000-00000.

de Bekker-Grob EW, Niers EJ, van Lanschot JJ, Steyerberg EW, Wijnhoven BP. Patients’ preferences for surgical management of esophageal cancer: a discrete choice experiment. World J Surg. 2015;39(10):2492–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-015-3148-8.

Damen TH, de Bekker-Grob EW, Mureau MA, Menke-Pluijmers MB, Seynaeve C, Hofer SO, et al. Patients’ preferences for breast reconstruction: a discrete choice experiment. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(1):75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2010.04.030.

de Bekker-Grob EW, Bliemer MC, Donkers B, Essink-Bot ML, Korfage IJ, Roobol MJ, et al. Patients’ and urologists’ preferences for prostate cancer treatment: a discrete choice experiment. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(3):633–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.370.

Malhotra C, Farooqui MA, Kanesvaran R, Bilger M, Finkelstein E. Comparison of preferences for end-of-life care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers: a discrete choice experiment. Palliat Med. 2015;29(9):842–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315578803.

Lathia N, Isogai PK, Walker SE, De Angelis C, Cheung MC, Hoch JS, et al. Eliciting patients’ preferences for outpatient treatment of febrile neutropenia: a discrete choice experiment. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(1):245–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1517-5.

Wong MK, Mohamed AF, Hauber AB, Yang JC, Liu Z, Rogerio J, et al. Patients rank toxicity against progression free survival in second-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Med Econ. 2012;15(6):1139–48. https://doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2012.708689.

Lee JY, Kim K, Lee YS, Kim HY, Nam EJ, Kim S, et al. Treatment preferences of advanced ovarian cancer patients for adding bevacizumab to first-line therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143(3):622–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.10.021.

Havrilesky LJ, Alvarez Secord A, Ehrisman JA, Berchuck A, Valea FA, Lee PS, et al. Patient preferences in advanced or recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(23):3651–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28940.

Tinelli M, Ozolins M, Bath-Hextall F, Williams HC. What determines patient preferences for treating low risk basal cell carcinoma when comparing surgery vs imiquimod? A discrete choice experiment survey from the SINS trial. BMC Dermatol. 2012;12:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-5945-12-19.

Bridges JF, Mohamed AF, Finnern HW, Woehl A, Hauber AB. Patients’ preferences for treatment outcomes for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a conjoint analysis. Lung Cancer. 2012;77(1):224–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.01.016.

Uemura H, Matsubara N, Kimura G, Yamaguchi A, Ledesma DA, DiBonaventura M, et al. Patient preferences for treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer in Japan: a discrete-choice experiment. BMC Urol. 2016;16(1):63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-016-0182-2.

Landfeldt E, Eriksson J, Ireland S, Musingarimi P, Jackson C, Tweats E, et al. Patient, physician, and general population preferences for treatment characteristics in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a conjoint analysis. Leuk Res. 2016;40:17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2015.11.006.

Caldon LJ, Walters SJ, Ratcliffe J, Reed MW. What influences clinicians’ operative preferences for women with breast cancer? An application of the discrete choice experiment. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(11):1662–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2007.04.021.

Morgan JL, Walters SJ, Collins K, Robinson TG, Cheung KL, Audisio R, et al. What influences healthcare professionals’ treatment preferences for older women with operable breast cancer? An application of the discrete choice experiment. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(7):1282–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2017.01.012.

Muhlbacher AC, Bethge S. Patients’ preferences: a discrete-choice experiment for treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Health Econ. 2015;16(6):657–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-014-0622-4.

Ossa DF, Briggs A, McIntosh E, Cowell W, Littlewood T, Sculpher M. Recombinant erythropoietin for chemotherapy-related anaemia: economic value and health-related quality-of-life assessment using direct utility elicitation and discrete choice experiment methods. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25(3):223–37. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200725030-00005.

Sculpher M, Bryan S, Fry P, de Winter P, Payne H, Emberton M. Patients’ preferences for the management of non-metastatic prostate cancer: discrete choice experiment. BMJ. 2004;328(7436):382. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.37972.497234.44.

Aristides M, Chen J, Schulz M, Williamson E, Clarke S, Grant K. Conjoint analysis of a new chemotherapy: willingness to pay and preference for the features of raltitrexed versus standard therapy in advanced colorectal cancer. Pharmacoeconomics. 2002;20(11):775–84. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200220110-00006.

Sung L, Alibhai SM, Ethier MC, Teuffel O, Cheng S, Fisman D, et al. Discrete choice experiment produced estimates of acceptable risks of therapeutic options in cancer patients with febrile neutropenia. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(6):627–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.008.

Johnson P, Bancroft T, Barron R, Legg J, Li X, Watson H, et al. Discrete choice experiment to estimate breast cancer patients’ preferences and willingness to pay for prophylactic granulocyte colony-stimulating factors. Value Health. 2014;17(4):380–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2014.01.002.

Weston A, Fitzgerald P. Discrete choice experiment to derive willingness to pay for methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy versus simple excision surgery in basal cell carcinoma. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22(18):1195–208. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200422180-00004.

Park MH, Jo C, Bae EY, Lee EK. A comparison of preferences of targeted therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma between the patient group and health care professional group in South Korea. Value Health. 2012;15(6):933–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2012.05.008.

Finkelstein E, Malhotra C, Chay J, Ozdemir S, Chopra A, Kanesvaran R. Impact of treatment subsidies and cash payouts on treatment choices at the end of life. Value Health. 2016;19(6):788–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2016.02.015.

Ngorsuraches S, Thongkeaw K. Patients’ preferences and willingness-to-pay for postmenopausal hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer treatments after failure of standard treatments. Springerplus. 2015;4:674. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-1482-9.

Eliasson L, de Freitas HM, Dearden L, Calimlim B, Lloyd AJ. Patients’ preferences for the treatment of metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer: a discrete choice experiment. Clin Ther. 2017;39(4):723–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.02.009.

Hechmati G, Hauber AB, Arellano J, Mohamed AF, Qian Y, Gatta F, et al. Patients’ preferences for bone metastases treatments in France, Germany and the UK. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(1):21–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2309-x.

Hauber AB, Gonzalez JM, Coombs J, Sirulnik A, Palacios D, Scherzer N. Patient preferences for reducing toxicities of treatments for gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:307–14. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S20445.

Lloyd A, Penson D, Dewilde S, Kleinman L. Eliciting patient preferences for hormonal therapy options in the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2008;11(2):153–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.pcan.4500992.

Muhlbacher AC, Lincke HJ, Nubling M. Evaluating patients’ preferences for multiple myeloma therapy, a discrete-choice-experiment. Psychosoc Med. 2008;5:Doc10.

Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health—a checklist: a report of the ISPOR good research practices for conjoint analysis task force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013.

US FDA. Public workshop on patient-focused drug development: Guidance 1—collecting comprehensive and representative input. 2017. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/public-workshop-patient-focused-drug-development-guidance-1-collecting-comprehensive-and. Accessed 28 Aug 2020.

US FDA. The voice of the patient: A series of reports from FDA’s patient-focused drug development initiative. 2017. https://www.fda.gov/industry/prescription-drug-user-fee-amendments/voice-patient-series-reports-fdas-patient-focused-drug-development-initiative. Accessed 28 Aug 2020.

Ikenwilo D, Heidenreich S, Ryan M, Mankowski C, Nazir J, Watson V. The best of both worlds: an example mixed methods approach to understand men’s preferences for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms. Patient. 2018;11(1):55–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-017-0263-7.

Janssen EM, Segal JB, Bridges JF. A framework for instrument development of a choice experiment: an application to type 2 diabetes. Patient. 2016;9(5):465–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-016-0170-3.

Ryan M, Watson V, Entwistle V. Rationalising the ‘irrational’: a think aloud study of discrete choice experiment responses. Health Econ. 2009;18(3):321–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1369.

Sosnowski R, Kulpa M, Zietalewicz U, Wolski JK, Nowakowski R, Bakula R, et al. Basic issues concerning health-related quality of life. Cent Eur J Urol. 2017;70(2):206–11. https://doi.org/10.5173/ceju.2017.923.

Trask PC, Hsu MA, McQuellon R. Other paradigms: health-related quality of life as a measure in cancer treatment: its importance and relevance. Cancer J. 2009;15(5):435–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181b9c5b9.

Calman KC. Quality of life in cancer patients—an hypothesis. J Med Ethics. 1984;10(3):124–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.10.3.124.

Ryan M. Using conjoint analysis to take account of patient preferences and go beyond health outcomes: an application to in vitro fertilisation. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(4):535–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00374-8.

Krahn M, Bremner KE, Tomlinson G, Ritvo P, Irvine J, Naglie G. Responsiveness of disease-specific and generic utility instruments in prostate cancer patients. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(3):509–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-006-9132-x.

Blazeby JM, Hall E, Aaronson NK, Lloyd L, Waters R, Kelly JD, et al. Validation and reliability testing of the EORTC QLQ-NMIBC24 questionnaire module to assess patient-reported outcomes in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;66(6):1148–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.034.

Wagner LI, Robinson D Jr, Weiss M, Katz M, Greipp P, Fonseca R, et al. Content development for the functional assessment of cancer therapy-multiple myeloma (fact-mm): use of qualitative and quantitative methods for scale construction. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2012;43(6):1094–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.06.019.

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the eastern cooperative oncology group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649–55.

de Bekker-Grob EW, Donkers B, Jonker MF, Stolk EA. Sample size requirements for discrete-choice experiments in healthcare: a practical guide. Patient. 2015;8(5):373–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-015-0118-z.

Hess S, Hensher D, Daly AJ. Not bored yet—revisiting respondent fatigue in stated choice experiments. Transp Res Part A Policy Pract. 2012;46(3):626–44.

Carlsson F, Mørkbak MR, Olsen SB. The first time is the hardest: a test of ordering effects in choice experiments. J Choice Model. 2012;5(2):19–37.

Bech M, Kjaer T, Lauridsen J. Does the number of choice sets matter? Results from a web survey applying a discrete choice experiment. Health Econ. 2011;20(3):273–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1587.

Muhlbacher AC, Sadler A, Lamprecht B, Juhnke C. Patient preferences in the treatment of hemophilia a: a best-worst scaling case 3 analysis. Value Health. 2020;23(7):862–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2020.02.013.

Ghijben P, Lancsar E, Zavarsek S. Preferences for oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: a best-best discrete choice experiment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(11):1115–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0188-0.

Krucien N, Watson V, Ryan M. Is best-worst scaling suitable for health state valuation? A comparison with discrete choice experiments. Health Econ. 2017;26(12):e1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3459.

Heidenreich S, Phillips-Beyer A, Flamion B, Ross M, Seo J, Marsh K. Benefit-risk or risk-benefit trade-offs? Another look at attribute ordering effects in a pilot choice experiment. Patient. 2021;14(1):65–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-020-00475-y.

Vass CM, Davison NJ, Vander Stichele G, Payne K. A picture is worth a thousand words: the role of survey training materials in stated-preference studies. Patient. 2020;13(2):163–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-019-00391-w.

Scarpa R, Rose JM. Design efficiency for non-market valuation with choice modelling: how to measure it, what to report and why. Aust J Agric Resour Econ. 2008;52(3):253–82.

Jackson Y, Flood E, Rhoten S, Janssen EM, Lundie M. Acrovoice: eliciting the patients’ perspective on acromegaly disease activity. Pituitary. 2019;22(1):62–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-018-00933-9.

Hauber B, Coulter J. Using the threshold technique to elicit patient preferences: an introduction to the method and an overview of existing empirical applications. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020;18(1):31–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-019-00521-3.

Tervonen T, Gelhorn H, Sri Bhashyam S, Poon JL, Gries KS, Rentz A, et al. Mcda swing weighting and discrete choice experiments for elicitation of patient benefit-risk preferences: a critical assessment. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(12):1483–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.4255.

Postmus D, Richard S, Bere N, van Valkenhoef G, Galinsky J, Low E, et al. Individual trade-offs between possible benefits and risks of cancer treatments: results from a stated preference study with patients with multiple myeloma. Oncologist. 2018;23(1):44–51. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0257.

Marsh K, Ijzerman M, Thokala P, Baltussen R, Boysen M, Kalo Z, et al. Multiple criteria decision analysis for health care decision making—emerging good practices: report 2 of the ISPOR MCDA emerging good practices task force. Value Health. 2016;19(2):125–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2015.12.016.

Bliemer MCJ, Rose JM, Chorus CG. Detecting dominance in stated choice data and accounting for dominance-based scale differences in logit models. Transp Res Part B Methodol. 2017;102:83–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trb.2017.05.005.

Tervonen T, Schmidt-Ott T, Marsh K, Bridges JFP, Quaife M, Janssen E. Assessing rationality in discrete choice experiments in health: an investigation into the use of dominance tests. Value Health. 2018;21(10):1192–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.04.1822.

Jonker MF, Donkers B, de Bekker-Grob EW, Stolk EA. Effect of level overlap and color coding on attribute non-attendance in discrete choice experiments. Value Health. 2018;21(7):767–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.10.002.

Maddala T, Phillips KA, Reed JF. An experiment on simplifying conjoint analysis designs for measuring preferences. Health Econ. 2003;12(12):1035–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.798.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Lauren Randall, Janet Dooley and Dawn Ri'chard for their support in editing and formatting this manuscript, and Rienne Schinner for her support in reviewing and executing the searches.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Conflict of interest

Hannah Collacott, Vikas Soekhai, Caitlin Thomas, Anne Brooks, Ella Brookes, Rachel Lo, Sarah Mulnick and Sebastian Heidenreich have no conflicts of interest to declare relevant to this study.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author’s contributions

HC, VS, CT, AB, RL, SM and SH participated in the conception, design, planning and conduct of the study, and analysis and interpretation of data.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Collacott, H., Soekhai, V., Thomas, C. et al. A Systematic Review of Discrete Choice Experiments in Oncology Treatments. Patient 14, 775–790 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-021-00520-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-021-00520-4