Abstract

Severe infection of infants with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a leading cause of morbidity in the developed world and mortality in the developing world. Prophylaxis using palivizumab in infants at risk for severe RSV disease reduces the rate of hospitalisation in this population of children. To ensure complete prophylaxis, infants must receive monthly doses over the winter season. To improve parental convenience, the Synacare® programme was implemented in Ireland and the Netherlands. Synacare® is now a longstanding programme in which palivizumab is administered in the home setting by skilled nurses. Protocols and procedures described here illustrate the efficiency and acceptability of the home delivery service of RSV disease prophylaxis. Post-administration surveys have indicated a high level of parental satisfaction with the programme. At-home paediatric programmes like Synacare® may serve as an alternative to burdensome monthly hospital visits and may lead to enhanced clinical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Infection with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) occurs in most children by 2 years of age [1, 2]. The virus is highly contagious and is spread through close exposure to individuals with infection and through contact with fomites or virus-laden large airborne particles [3–5]. Although most children experience only mild (or no) symptoms, severe RSV disease may require hospitalisation [6, 7] and may be associated with an increased risk of wheezing and/or asthma later in life [8–10]. Severe RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease is an important cause of mortality among young children in the developing world [11].

Risk factors for severe RSV disease in children include preterm birth [12–14], the presence of chronic lung disease of prematurity (CLDP; also known as bronchopulmonary dysplasia [BPD]) and haemodynamically significant congenital heart disease (hsCHD) [15, 16]. The rate of RSV infections throughout the year typically changes in a seasonal manner that is dependent on a number of geographic and climatic factors; virulence per RSV season may also vary [17]. The RSV season in temperate climates of the Northern Hemisphere generally begins in October and extends until March or April, with a peak between December and February [17, 18], although some annual variation exists [19]. The somewhat predictable nature of the RSV season onset permits nurses, physicians, and other healthcare workers to prepare for an expected increase in RSV infection cases.

Currently, no vaccine is available for the prevention of RSV infection. The management of severe RSV infection generally consists of supportive measures, such as maintenance of adequate hydration and oxygenation [20].

Palivizumab (Synagis®, MedImmune, LLC, and AbbVie Inc.), a humanised monoclonal antibody specific for the RSV F protein, inhibits binding of the virus to host cells and fusion of infected cells with adjacent cells [21]. Prophylaxis with palivizumab has been shown to decrease the rate of hospitalisation due to RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease in the population of infants born prematurely [≤35 weeks gestational age (wGA)] and children <24 months of age with BPD or hsCHD [22, 23].

Palivizumab is administered intramuscularly (15 mg/kg) to infants monthly beginning before the expected start of the RSV season [24, 25]. Maintenance of serum anti-RSV immunoglobulin concentrations during the RSV season is necessary for decreasing the risk of severe RSV disease [21].

Outpatient administration of palivizumab typically occurs in the hospital, physician’s office, or specifically dedicated clinic, which requires transportation of the infant to the site of prophylaxis administration. For some families, economic, logistical, and/or work considerations may make it difficult to bring their infant to receive the monthly injection, especially in cases of multiple births, other comorbidities, long travel distances, or if young siblings need to be brought to the visit. These issues have the potential to decrease adherence, and thus adversely affect the maintenance of protective serum palivizumab concentrations in these at-risk infants.

Home-based palivizumab administration has been shown to reduce the number of RSV-associated and all-cause hospitalisations compared with the administration of palivizumab in the medical office or clinic [26, 27]. The potential reasons for this reduction have been postulated to be increased adherence with palivizumab prophylaxis and removal of the requirement to enter a busy hospital or physician’s office during the RSV endemic months, thereby reducing the risk of pathogen exposure. For these reasons, a programme of home-based palivizumab administration (Synacare®, AbbVie) was established in the Netherlands in 2003 and in Ireland in 2008, where previously parents had to attend monthly prophylaxis clinics at the hospital. To date, these two countries are the only ones to have a national home-based delivery programme. Trained nurses visit the homes of infants to administer palivizumab. The similarities and differences between the Irish and Dutch Synacare® programmes, documented in this review, illustrate the idiosyncrasies and potential advantages of each system.

RSV prophylaxis overview

In Ireland and the Netherlands, palivizumab is indicated for children born at ≤35 wGA and 32 wGA, respectively, and <6 months of age at the onset of the RSV season; children <2 years of age requiring treatment for BPD within the last 6 months; and children <2 years of age with hsCHD. The presumed start of the RSV season, and the start of prophylaxis with palivizumab, is often set by regional healthcare authorities based on historical data in those areas. A recent analysis of Canadian data found that the most effective method of determining the start of the RSV season was through the surveillance of virology data from local laboratories, assuming a 2-day turnaround in laboratory results [28]. In Ireland and the Netherlands, the RSV season usually extends from September/October through March/April and palivizumab prophylaxis typically begins in early October. In Ireland, prophylaxis begins during the first week of October or after confirmation of increasing positive cases by the National Virus Reference Laboratory.

Infants eligible for RSV prophylaxis

Eligibility for palivizumab and the Synacare® service is decided by the attending paediatrician; in Ireland, each hospital has its own internal RSV prophylaxis eligibility guidelines. Further, in Ireland, all prescriptions are reimbursed, with some families contributing to the cost via a capped monthly pay scheme. The cost of prophylaxis for Irish parents is partly or fully covered by the Irish healthcare system under a special social services insurance scheme. Some families with limited financial income are eligible for full drug cost coverage by the Health Services Executive (HSE) Medical Card [29]. Under the Drugs Payment Scheme (as of January 2013), parents with higher incomes pay a capped price of €144 per month for family medications, which include palivizumab prophylaxis. This charge covers the entire family, meaning that if the infant or any other member of the household receives additional medications during this month, the household charge is still capped at €144.

In the Netherlands, there is national guidance [“Standpunt NVK ‘Passieve immunisatie tegen RSV-ziekte” (Dutch Paediatric Society Position on Passive Immunisation Against RSV Disease) and “Wijziging regeling zorgverzekering” (Amendments to Insurance Regulations)] that describes the population of patients that should receive palivizumab prophylaxis (Table 1) [30] and those who are eligible for reimbursement [31]. In the Netherlands, it is a requirement for all citizens to have health insurance, which covers the cost of palivizumab according to these guidelines.

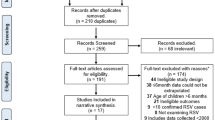

Issuance of the prescription

In Ireland (Fig. 1a), palivizumab is prescribed on a ‘High tech’ paper prescription and is usually limited to five doses if the baby is born before the RSV season commences (a sixth dose may be prescribed to particularly vulnerable infants during a prolonged RSV season). ‘High tech’ medicines are generally prescribed or initiated in the hospital and supplied through community pharmacies. The Synacare® provider, in communication with parents/guardians, ensures that the parent delivers the prescription to their designated pharmacy and helps the parent inform the pharmacist of the approximate weight of the patient. The Synacare® service then reminds the parents/guardians to collect the prescribed palivizumab 2 days before the first scheduled visit and each subsequent visit.

In the Netherlands (Fig. 1b), the prescription is electronically generated and issued to the care provider wholesaler who confirms that the prescription is reimbursable with the health insurance company of the patient. Once reimbursement is confirmed, palivizumab is shipped to the appropriate pharmacy. The prescription, in all but exceptional cases, is one 100-mg vial and one 50-mg vial of palivizumab to ensure sufficient drug is available for dosing. The palivizumab is collected from the patient’s pharmacy by the Synacare® nurse just before each home visit. Unused, non-reconstituted palivizumab is stored by the parent. Subsequent doses are coordinated by the Synacare® service and the local pharmacy with approval from the insurance company.

In-home administration

The in-home processes for the administration of palivizumab in Ireland and the Netherlands are similar in many respects, but also possess a number of unique characteristics. The duration of the home visit in both Ireland and the Netherlands is ≈1.0–1.5 h for the first visit (which includes a parental educational component) and then 0.75–1 h for each subsequent visit.

Typically, infants born during the RSV season in Ireland receive their first dose of palivizumab in the hospital, preferably 2 days before discharge, whereas subsequent doses may be given at home. In contrast, infants born in the Netherlands are registered in the Synacare® service during their initial hospital stay and will receive palivizumab for the first time at home. In both countries, infants who require prolonged hospitalisation during the winter months receive palivizumab monthly whilst in the hospital, and in cases where infants are considered to be at high risk because of conditions such as severe cardiac comorbidities, the attending physician may decide that prophylaxis should be medically supervised in a hospital environment, and therefore, all doses may be administered in the hospital setting. For infants born outside the winter season, the hospital discharging nurse (or other appropriate nurse) is responsible for informing the infant’s parents/guardians regarding the RSV prophylaxis home service for which the infant is eligible. The parents are also given information regarding RSV infection and RSV prevention measures. Parents of infants who were born outside of the RSV season receive a phone call from the Synacare® home service team just before the onset of the RSV season. Through this initial call, the team confirms that the correct infant information is recorded, describes the home service, schedules the first appointment, and gives information regarding the prescription for palivizumab.

An informal home-risk assessment is completed by the nurse for all first visits. A general assessment includes a verbal consent and parent signature (to proceed with injection), a general assessment of the infant’s physical condition, a baseline check (body temperature, respiratory rate and heart rate), calculation of dose based on infant weight and preparation and injection of palivizumab. An additional 10–20 min is allotted to assess any potential adverse reactions and to complete any administrative paperwork, which is often recorded electronically.

In Ireland and the Netherlands, the Synacare® nurses are responsible for reporting all adverse events (AEs), including those that may not be serious and those that may not be considered to be related to palivizumab administration. In the Netherlands, the Synacare® nurse reports all AEs to the pharmacy, which also links to an AbbVie database (for pharmacovigilance reporting). This process may diminish the underreporting of AEs [32, 33]. However, the incidence of AEs related to palivizumab injection is generally low [22, 23]. In Ireland, Synacare® homecare nurses are also responsible for reporting all AEs to the local AbbVie pharmacovigilance officer who then reports the events to the Health Products Regulatory Authority.

In Ireland, subsequent visits are scheduled and confirmed 1 week in advance of the proposed visit to ensure compliance. If the most recent weight is not available from the parent, the weight will be estimated for the first prescription based on the most recent hospital records. The infant will then be weighed before administration of palivizumab at home. To ensure that prophylaxis is administered on the correct date, up to three different nurses may visit the infant and parents during the RSV season to accommodate the nurses’ availability. Before visiting the home, each nurse electronically reviews patient details and notes. The day before the visit, the nurse confirms the visit time and ensures that palivizumab has been collected and is being refrigerated in the infant’s home. Approximately ten nurses are involved in the Synacare® programme in Ireland, each of whom can perform four (rural) to six (city) visits per day.

All Synacare® homecare nurses are fully qualified paediatric nurses and receive training from a commercial provider of direct-to-patient services and AbbVie before commencing any homecare visits. In addition, the homecare service is able to liaise with a hospital-based clinical nurse specialist based in the main paediatric hospital in Ireland who coordinates the prophylaxis programme to ensure that infants scheduled for home administration still receive prophylaxis if they are hospitalised after discharge to ensure continuity of coverage.

For additional training purposes, a twice-yearly meeting of hospital-based neonatal nurses and Synacare® neonatal and paediatric nurses with responsibility for severe RSV disease prophylaxis is held in Ireland to exchange experiences regarding best practices. One meeting is held at the beginning of the RSV season and a review meeting takes place at the end of the season.

The home service in the Netherlands is led by the individual nurse assigned to a specific patient. Homecare nurses in the Netherlands have a great deal of independence in the planning and execution of the home visit process. The patient interaction begins with contact by a nurse from the home service and/or from the hospital shortly before discharge. The paediatrician usually speaks with parents on a weekly basis. All attempts are made to ensure that the same nurse is assigned to the same infant for all visits. This allows the nurse to consistently monitor the infant during the entire series of injections and may provide parents with a greater level of comfort. An appointment for the next visit is scheduled before departure from the home and parents complete a home visit assessment form during the first visit. Approximately 60 nurses in the Netherlands are involved in the Synacare® programme and because travel distances are relatively short, nurses can perform 7 to 8 visits per day.

In the Netherlands, annual training of nurses is conducted by AbbVie. The nurses have neonatal care experience and regular regional meetings allow nurses to increase their knowledge base regarding best practices that reduce RSV infection. In addition, nurses are made aware that any question from parents that cannot be adequately answered should be referred to the hospital or the paediatrician.

Parent/guardian education

The education of parents is of major importance to the health of the infant. The role of the home nurse is critical in reinforcing the messages about practices that will help reduce the risk of RSV infection [34, 35]. Before discharge, parents meet with a nurse responsible for discharge planning. Greater understanding of the need for RSV prophylaxis for at-risk infants may help to increase adherence, reduce stress and anxiety, and enhance clinical outcomes. Parents are provided with written material advising them of the importance of reducing the risk of RSV infection and explaining the Synacare® programme.

It is important that parents understand the rationale for palivizumab administration and the requirement for monthly dosing to maintain antibody levels. Information shared with the parents includes discussions regarding the disease state, RSV prophylaxis, and how the medication works [22, 23, 36]. Parents are also advised that palivizumab administration will not prevent every respiratory illness, such as influenza, and that concomitant administration of palivizumab and childhood vaccines is not contraindicated [37].

The importance of prevention measures to decrease the number of infections during annual periods of peak RSV infection is emphasised. Parents are advised to wash hands, to avoid crowds, and to avoid their child’s exposure to tobacco smoke [34]. Parents are directed toward online information regarding RSV and the prevention of infection (Table 2) and toward locally produced, physician-endorsed paper-based information. It is important that the websites identified contain accurate and up-to-date information that is written at a level that most parents can understand and use.

In Ireland, parental education regarding the reduction of RSV infection begins with the hospital nurse and, from the moment the baby enters the neonatal intensive care unit (ICU), a discharge plan is prepared, including educational activities and exchanges. Larger neonatal units have dedicated discharge planning nurses who may also have responsibility for the RSV programme. They can provide parents with an early link into the Synacare® programme and provide ongoing support and education. Close to the time of discharge, all parents are invited to attend a pre-discharge class. This class is generally held weekly and includes a resuscitation demonstration, information regarding safe sleeping guidelines, RSV exposure prevention, the importance of breastfeeding, preparation of formula feeds, childhood vaccination schedules, and information regarding follow-up post-discharge. Parents are provided with take-home material containing information from this class. A number of websites containing useful information regarding RSV are recommended by nurses [38]. Posters displayed in neonatal unit corridors, in breastfeeding rooms, and in paediatric outpatient areas are also used for parental educational purposes. An educational booklet (in English, French, and Polish) containing information on the Synacare® programme is provided to parents. In Ireland, parents often use the nurse homecare visit as an opportunity to ask general child healthcare questions.

In the Netherlands, parental education is mainly provided by the homecare nurses responsible for administering palivizumab. The first contact with a homecare nurse often takes place after discharge from the hospital. At discharge from the neonatal ward, parents receive an instruction booklet (“Home with the baby”) that provides parents with information regarding the care of a premature infant. Parents are also able to ask questions regarding homecare at the infant discharge. At this time, parents are instructed in ways to minimise their infant’s risk of RSV infection, such as hand washing and avoidance of exposure to tobacco smoke, day care, crowded areas, and people who have symptoms of colds. At this time, parents are also provided details on the Synacare® programme. Educational material can be found in documents and a website provided by the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment [39], in informational material supplied by AbbVie, and on websites of parent/guardian support groups [40, 41]. A specialised magazine, Vroegertje (Little early starter), and a website, Te Vroeg Geboren (Premature birth), contain information useful to parents with infants at risk of severe RSV infection [42]. The magazine is updated yearly and is distributed to hospitals and ICUs. The Synacare® provider also distributes an information package (in Dutch, English, French, Turkish, and Arabic) to parents. The package contains information intended to help parents reduce the risk of RSV infection and provides useful websites.

Home service and parental satisfaction

In both countries, surveys were conducted in which the overall objective of the research was to ascertain the parent’s/guardian’s satisfaction with the Synacare® Home Service. More specifically, data were collected regarding parental perceptions of the Synacare® Home Service, strengths, weaknesses, and gaps in the Home Service, and priorities for improvement. Data were collated only from those contacted or those parents that completed the questionnaire. The percentage of non-responders was not collected.

In Ireland, telephone surveys were conducted in 2008 (n = 111), 2009 (n = 100), and 2011 [n = 50 (by 2011, in Ireland, because of refinements in the service made due to feedback, a smaller sample size could be used for the survey)], representing 10–20 % of the total households in which infants received RSV prophylaxis in that year. Parents of infants who received palivizumab at home were asked questions to determine their satisfaction with the homecare service. Overall satisfaction with homecare was at or near 100 % for the parents contacted for the 3 years in which surveys were conducted (Fig. 2a). All survey respondents considered homecare to be superior to hospital care (Fig. 2b). Respondents felt that homecare directly saved them ≈4 h of time and €81 relative to prophylactic treatment administered at the hospital. The majority of respondents in 2011 (72 %) cited convenience as the reason for preferring homecare. More than 90 % of respondents stated that various aspects of their experience with home health nurses were “excellent” in the three surveys (Fig. 3a–d).

Satisfaction among Irish parents with the home service nurse in relation to a how good the nurse is at dealing with the child, b how thoroughly the nurse examines the child before giving the injection, c how well the nurse answers my questions, and d arriving on time on a scale of 1–5, with 5 being excellent. n = 111, 100 and 50 in 2008, 2009 and 2011, respectively

Parental surveys were conducted in the Netherlands by the nurses at the time of one of the scheduled visits. Parents were given a questionnaire and asked to anonymously complete and return it to the nurse on that day’s visit. For the winter seasons 2011–2012 and 2012–2013, 970 and 1009 parents completed the questionnaires, respectively, representing ≈20 % of the infants who received palivizumab prophylaxis that season. Parents expressed overall satisfaction with the Synacare® programme (from prescription to administration), with 68 % of respondents choosing the highest rating (“very good”) and 31 % choosing “good” in both surveys (Fig. 4a). Most survey respondents preferred home prophylaxis to receiving palivizumab at the doctor’s office or hospital (Fig. 4b). Most respondents considered the nurse who administered prophylaxis to be “very good” in both surveys (Fig. 5).

a Overall satisfaction among Dutch parents with children in the Synacare® programme; no respondents chose “bad”, “inadequate”, or “moderate” options on either survey; 1 % did not complete this question in both surveys. b Preference for palivizumab administration in the home setting compared with a doctor’s office or hospital; 4 % did not complete the survey in 2011–2012 and 2 % did not complete the survey in 2012–2013. n = 970 and 1009 for the 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 RSV seasons, respectively

Parents’ ratings of homecare nurses providing Synacare® in the Netherlands. No respondents chose “bad” or “inadequate” options. 1 % of respondents did not complete this question in both surveys; 1 % of respondents chose “Moderate” in 2012–2013. n = 970 and 1009 for the 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 RSV seasons, respectively

Discussion

Although the homecare systems in Ireland and the Netherlands differ, they both deliver the same fundamental service by providing an efficient and appreciated method of administering palivizumab in the home setting. They also provide the attending physician with useful updates regarding the health of the infant, including any AEs, and allow caregivers the opportunity to speak with a trained nurse to discuss basic healthcare issues.

Table 1 lists the infants eligible for palivizumab prophylaxis in each country. In the Netherlands, there is national guidance on infant eligibility [30], whereas in Ireland, the eligibility criteria are driven by the prescribing hospital. This explains why, in Ireland, not every infant meeting the guidelines in Table 1 is eligible for RSV prophylaxis. In both countries, physicians are entitled to prescribe at their own clinical discretion, resulting in different prescribing practices throughout each programme.

Several authors have commented that it seems counter-intuitive that parents would take their infants into a clinic or even to their doctor’s office to have a prophylactic injection where they are likely to be exposed to sick children in the waiting room [27, 43, 44]. At-home prophylaxis with palivizumab, as demonstrated in the Synacare® programmes in Ireland and the Netherlands, appears to provide holistic benefits to at-risk infants and their families. As with the care of the elderly in their home setting, extremely vulnerable infants should be extended the benefits of homecare, where possible.

Furthermore, physicians and parents support the idea of reducing the number of neonatologist, paediatrician, or general practitioner visits by five or six (i.e. one visit for each RSV dose) during the RSV season [44]. A prospective observational study in the United States reported that prophylaxis with palivizumab decreased RSV hospitalisations in at-risk infants, with patients receiving administration at home having the lowest rates of hospitalisation [45]. Compliance was significantly higher with a home-based rather than a clinic-based system and was associated with a decrease in hospitalisations and fewer unscheduled medical visits [27, 45]. The authors stated that home-based delivery of RSV prophylaxis may be more efficacious in preventing disease through increased compliance and decreased exposure of the high-risk infant to the clinic environment [27, 45].

Mechanisms to reduce an infant’s risk of serious RSV infection and to reduce travelling expenses and stress are especially important because parents of premature children have often already experienced a number of stressful situations involving the infant (i.e. neonatal ICU stay, mechanical ventilation, supplemental oxygen requirement), and/or possible maternal adverse health events (i.e. ruptured membranes that may have led to the premature birth of the child). These stressful experiences may continue to impact parents through the first year of the infant’s life and beyond.

For a number of conditions, treatment of patients using a homecare model has been shown to have both clinical and economic advantages compared with traditional care in a hospital, clinic, or physician’s office [46–48]. The administration of palivizumab using a homecare model has been shown to increase compliance, which is expected to reduce RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease hospitalisations [26, 45]. At-home palivizumab administration in Ireland and the Netherlands, through the Synacare® programme, would be expected to have similar clinical (and economic) advantages over administration in the hospital.

In both the Netherlands and Ireland, the Synacare® service is fully funded by AbbVie, the supplier of palivizumab. In Ireland, >3500 infants have been treated during the 5 years of the Synacare® programme, resulting in an estimated decrease of hospital outpatient appointments of ≈14,000 [49]. This decrease in workload for palivizumab administration frees up time at the clinic/hospital for the already overstretched nurses and other medical staff in the clinics. It is difficult to quantify the cost savings to the healthcare system; however, using the cost of one vaccination visit, as detailed by the Health Service Executive of Ireland, of €42.75 per general practitioner visit [50], this would result in a cost saving of €595,500. Likewise, in the Netherlands, the cost of one general practitioner visit would be €18.08 plus materials [51] and a hospitalisation treatment visit of a newborn child in neonatology would be €190.00 [52]. In addition, the time required for the parents to take the infant to the hospital and wait in a paediatric ward is not required. A study is ongoing in Ireland to quantify the total cost savings of the Synacare® programme, including the costs of potential increased wastage of palivizumab due to lost batching opportunities (i.e. the use of a single medication vial to treat multiple eligible children). In addition, this study will review compliance and efficacy, comparing RSV seasonal clinical outcome data before and after the introduction of the Synacare® programme in Ireland.

Homecare also allows parents a greater opportunity for interaction with the visiting nurse, with more time for questions and answers in their own familiar home environment. Parental survey responses demonstrate parental satisfaction with the Synacare® programme and with the nurses who provide the care. As an added benefit, in-home prophylaxis is less stressful for the child. Before home administration, infants were brought to busy outpatient departments, with visits often taking up to 2 hours.

At-home prophylaxis of palivizumab, as demonstrated in the Synacare® programmes in Ireland and the Netherlands, appears to provide both clinical benefits to at-risk infants and their families and economic benefits to regional healthcare systems. Although more formal studies comparing homecare with hospital palivizumab prophylaxis may be necessary to determine any potential clinical and/or economic advantages, the information provided here suggests that additional countries may derive benefit from programmes such as Synacare®.

Conclusion

In summary, both the Irish and the Netherlands homecare systems consist of the following key elements critical to their success:

-

Agreement and trust between the hospital caregivers and homecare providers. This is based on open communication and feedback on patient status to the hospital care team.

-

An organised appointment set-up process to meet parents’ needs and schedules and to ensure the most optimal use of the home nurses’ time.

-

Well-trained home nurses to provide the RSV prophylaxis, to review and report on the infant’s general health, and to ensure that parents have all of the information necessary to help prevent RSV infection.

-

Ongoing review to ensure that the health of the infant and the value of the service to the parents are as good as possible year after year.

-

Removal of hospital outpatient visits from the healthcare system, with avoidance of monthly visits for each infant receiving palivizumab prophylaxis.

References

Enders G. Paramyxoviruses. In: Baron S, editor. Medical microbiology. 4th ed. Galveston: University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996.

Glezen WP, Taber LH, Frank AL, et al. Risk of primary infection and reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140(6):543–6.

Hall CB. Respiratory syncytial virus. In: Feigin RD, Cherry JD, editors. Textbook of pediatric infectious diseases. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co.; 1981. p. 1247–67.

Hall CB, Douglas RG Jr, Geiman JM. Possible transmission by fomites of respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis. 1980;141(1):98–102.

Lindsley WG, Blachere FM, Davis KA, et al. Distribution of airborne influenza virus and respiratory syncytial virus in an urgent care medical clinic. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(5):693–8.

Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):588–98.

Blanken MO, Rovers MM, Molenaar JM, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus and recurrent wheeze in healthy preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(19):1791–9.

Bacharier LB, Cohen R, Schweiger T, et al. Determinants of asthma after severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(1):91–100 e3.

Escobar GJ, Ragins A, Li SX, et al. Recurrent wheezing in the third year of life among children born at 32 weeks’ gestation or later: relationship to laboratory-confirmed, medically attended infection with respiratory syncytial virus during the first year of life. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(10):915–22.

Sigurs N, Aljassim F, Kjellman B, et al. Asthma and allergy patterns over 18 years after severe RSV bronchiolitis in the first year of life. Thorax. 2010;65(12):1045–52.

Nair H, Nokes DJ, Gessner BD, et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9725):1545–55.

Carbonell-Estrany X, Quero J, IRIS Study Group. Hospitalization rates for respiratory syncytial virus infection in premature infants born during two consecutive seasons. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20(9):874–9.

Leader S, Kohlhase K. Recent trends in severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) among US infants, 1997 to 2000. J Pediatr. 2003;143(5 Suppl):S127–32.

Rossi GA, Medici MC, Arcangeletti MC, et al. Risk factors for severe RSV-induced lower respiratory tract infection over four consecutive epidemics. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166(12):1267–72.

Kristensen K, Hjuler T, Ravn H, et al. Chronic diseases, chromosomal abnormalities, and congenital malformations as risk factors for respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization: a population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(6):810–7.

Meert K, Heidemann S, Lieh-Lai M, et al. Clinical characteristics of respiratory syncytial virus infections in healthy versus previously compromised host. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1989;7(3):167–70.

Bloom-Feshbach K, Alonso WJ, Charu V, et al. Latitudinal variations in seasonal activity of influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV): a global comparative review. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e54445.

Stensballe LG, Devasundaram JK, Simoes EA. Respiratory syncytial virus epidemics: the ups and downs of a seasonal virus. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(2 Suppl):S21–32.

Tatochenko V, Uchaikin V, Gorelov A, et al. Epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus in children ≤2 years of age hospitalized with lower respiratory tract infections in the Russian Federation: a prospective, multicenter study. Clin Epidemiol. 2010;2:221–7.

Dawson-Caswell M, Muncie HL Jr. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in children. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(2):141–6.

Johnson S, Oliver C, Prince GA, et al. Development of a humanized monoclonal antibody (MEDI-493) with potent in vitro and in vivo activity against respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis. 1997;176(5):1215–24.

Feltes TF, Cabalka AK, Meissner HC, et al. Palivizumab prophylaxis reduces hospitalization due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children with hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease. J Pediatr. 2003;143(4):532–40.

The IMpact-RSV Study Group. Palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibody, reduces hospitalization from respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk infants. Pediatrics. 1998;102(3):531–7.

Committee on Infectious Diseases. From the American Academy of Pediatrics: policy statement—modified recommendations for use of palivizumab for prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infections. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1694–701.

Palivizumab: full prescribing information. Gaithersburg: MedImmune; 2014.

Frogel MP, Stewart DL, Hoopes M, et al. A systematic review of compliance with palivizumab administration for RSV immunoprophylaxis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010;16(1):46–58.

Hand IL, Noble L, Geiss D, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus immunoprophylaxis in an urban population: a comparison of delivery strategies and outcomes. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(2):175–6.

Paes BA, Craig C, Pigott W, et al. Seasonal respiratory syncytial virus prophylaxis based on predetermined dates versus regional surveillance data. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(9):e360–4.

Health Service Executive. Your guide to medical cards. http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/1/schemes/mc/about/. Accessed 25 Aug 2015.

Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde. Standpunt NVK ‘Passieve immunisatie tegen RSV-ziekte’. http://www.nvk.nl/Kwaliteit/Standpunten/RSVziekte/tabid/302/language/nl-NL/Default.aspx. Accessed 25 Aug 2015.

Hoogervorst JF. Wijziging regeling zorgverzekering. https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/stcrt-2006-218-p29-SC77527.pdf. Accessed 25 Aug 2015.

Biagi C, Montanaro N, Buccellato E, et al. Underreporting in pharmacovigilance: an intervention for Italian GPs (Emilia-Romagna region). Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(2):237–44.

Perez Garcia M, Figueras A. The lack of knowledge about the voluntary reporting system of adverse drug reactions as a major cause of underreporting: direct survey among health professionals. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(12):1295–302.

Bracht M, Basevitz D, Cranis M, et al. Strategies for reducing the risk of respiratory syncytial virus infection in infants and young children: a Canadian nurses’ perspective. Neonatal Netw. 2012;31(6):357–68.

Di Carlo P, Romano A, Plano MR, et al. Children, parents and respiratory syncytial virus in Palermo, Italy: prevention is primary. J Child Health Care. 2010;14(4):396–407.

Simoes EA, Groothuis JR, Carbonell-Estrany X, et al. Palivizumab prophylaxis, respiratory syncytial virus, and subsequent recurrent wheezing. J Pediatr. 2007;151(1):34–42, e1.

Checchia PA, Nalysnyk L, Fernandes AW, et al. Mortality and morbidity among infants at high risk for severe respiratory syncytial virus infection receiving prophylaxis with palivizumab: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(5):580–8.

Olabarrieta I, Gonzalez-Carrasco E, Calvo C, et al. Hospital admission due to respiratory viral infections in moderate preterm, late preterm and term infants during their first year of life. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2014;43(5):469–73.

Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu. RSV-infectie. B97.4. http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&frm=1&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CDUQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.zorg-en-gezondheid.be%2FWorkArea%2FDownloadAsset.aspx%3Fid%3D33545&ei=4hNwUrGOHqrC4AO0ooC4BQ&usg=AFQjCNFoIlBQOi_sROyKTJrYLe46JEc5RQ. Accessed 25 Aug 2015.

Vereniging van Ouders van Couveusekinderen. RSV: meer dan een verkoudheid. http://voc.rjbtest.nl/data/files/RSV-folder%20ZW%202009.pdf. Accessed 25 Mar 2015.

Vereniging van Ouders van Couveusekinderen. RSV. http://www.couveuseouders.nl/index/805. Accessed 29 Oct 2013.

Te Vroeg Geboren. http://www.tevroeggeboren.nl/. Accessed 25 Aug 2015.

Goldenring J. Give Synagis via home health. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):219.

Schipper JA. Give Synagis via home care: a reply. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6):1258–9 (author reply 9).

Frogel M, Nerwen C, Cohen A, et al. Prevention of hospitalization due to respiratory syncytial virus: results from the Palivizumab Outcomes Registry. J Perinatol. 2008;28(7):511–7.

Cryer L, Shannon SB, Van Amsterdam M, et al. Costs for ‘hospital at home’ patients were 19 percent lower, with equal or better outcomes compared to similar inpatients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6):1237–43.

Marsteller JA, Burton L, Mader SL, et al. Health care provider evaluation of a substitutive model of hospital at home. Med Care. 2009;47(9):979–85.

Polinder S, Verschuur EM, Siersema PD, et al. Cost comparison study of two different follow-up protocols after surgery for oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(12):2110–5.

Ohuma EO, Okiro EA, Ochola R, et al. The natural history of respiratory syncytial virus in a birth cohort: the influence of age and previous infection on reinfection and disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(9):794–802.

HSE Finance Shared Services Primary Care Reimbursement Service. Schedule of Fees and Allowances Payable to Doctors Participating in the General Medical Services Scheme and other Community Schemes. http://www.icgp.ie/go/library/catalogue/item/30CC3830-D34E-4CCA-A8D97B475B1754C1/. Accessed 25 Aug 2015.

Nederlanse Zorgautoriteit. BIJLAGE 1 BIJ TARIEFBESCHIKKING TB/CU-7089-01. TARIEVENLIJST HUISARTSENZORG EN MULTIDISCIPLINAIRE ZORG http://www.nza.nl/98174/139255/1036985/bijlagemap/Bijlage_bij_TB-CU-7089-01_Huisartsenzorg_en_multidisciplinaire_zorg.pdf. Accessed 25 Aug 2015.

Doktersrekening.nl. Wat kost uw behandeling in de zorg: inzicht in prijzen. http://www.doktersrekening.nl/index.php?zoekstring=990017018. Accessed 25 Aug 2015.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by J.E. Fincke, PhD, and D.E. McCallus, PhD, of Complete Publication Solutions, LLC (North Wales, PA, USA); this support was funded by AbbVie Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding source

AbbVie Inc.

Conflict of interest/disclosure information

BW has received honoraria from AbbVie. EM, ET, and AvV have no conflicts to disclose. EM and LL are employees of Eurocept Homecare. AM is an employee of TCP Homecare Limited. FJC, SV, and GN are employees of and may hold stock or stock options in AbbVie. The Synacare® programme is funded by AbbVie. Because some of the authors are employees of AbbVie, the role of the sponsor (AbbVie) included contributions to the writing, review, and approval of this manuscript.

Ethical standards

The manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data. There was no secondary analysis of the patient satisfaction survey results. Only the results from the patient satisfaction survey are available. These results were collected as, and fall under the definition of, market research. According to the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association Code of Conduct (http://www.ephmra.org/code-of-conduct/11/B-What-Constitutes-Market-Research), “Market research is the systematic gathering and interpretation of information about individuals or organisations using the statistical and analytical methods and techniques of the applied social sciences to gain insight or support decision making. The identity of respondents will not be revealed to the user of the information without explicit consent and no sales approach will be made to them as a direct result of their having provided information.”

“…Market research (as defined above) relating to market or consumer behaviour of the sort that pharmaceutical companies routinely commission, whether involving healthcare professionals, patients, carers or members of the public does not require Clinical Research Ethics Committee or Independent Review Board approval (Institutional Review Board in the USA).”

According to the European Network of Research Ethics Committees, in Ireland, there is currently no specific legislation for research involving human subjects other than those involving medicinal products. In the Netherlands, if a study falls under the scope of the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO), then it must undergo a prior review by an accredited MREC or the CCMO (the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects). According to their definitions (http://www.ccmo.nl/en/your-research-does-it-fall-under-the-wmo), this marketing research does not fall under the scope of the WMO and therefore did not require ethics committee approval.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Whelan, B., Musters, E., Murray, A. et al. Review of the home care programmes for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) prophylaxis in Ireland and The Netherlands. Drugs Ther Perspect 32, 119–130 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-015-0275-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-015-0275-0