Abstract

Background

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) interchangeability guidelines state that the primary endpoint in a switching study should assess the impact of switching between the proposed interchangeable product and the reference product on clinical pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (if available), as these assessments are generally sensitive to changes in immunogenicity and/or exposure that may arise due to switching. In addition, interchangeability designation requires no clinically meaningful difference in safety and efficacy of switching between the biosimilar and reference, compared with when using the reference product alone.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate the PK, immunogenicity, efficacy, and safety in participants undergoing repeated switches between Humira® and AVT02 as part of a global interchangeable development program.

Methods

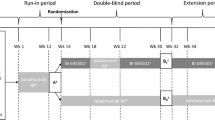

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis comprises three parts: lead-in period (weeks 1–12), switching module (weeks 12–28), and the optional extension phase (weeks 28–52). Following the lead-in period during which all participants received the reference product (80 mg in week 1, followed by 40 mg every other week), participants with a clinical response of ≥ 75% improvement in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI75) were randomized 1:1 to receive AVT02 alternating with the reference product (switching arm) or reference product only (non-switching arm). At week 28, participants who were PASI50 responders could opt to take part in an open-label extension phase receiving AVT02 up to week 50, with an end of study visit at week 52. PK, safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy were evaluated at various timepoints throughout the study for both switching and non-switching arms.

Results

In total, 550 participants were randomized to switching (277) and non-switching arms (273). The switching versus non-switching arithmetic least square means ratio [90% confidence intervals (CIs)] was 101.7% (91.4–112.0%) for the area under the concentration–time curve over the dosing interval from weeks 26–28 (AUCtau, W26–28) and 108.1% (98.3–117.9%) for maximum concentration over the dosing interval from weeks 26–28 (Cmax, W26–28). The 90% CIs for the switching versus non-switching arithmetic means ratio for primary endpoints AUCtau, W26–28 and Cmax, W26–28 were within the prespecified limits of 80–125%, demonstrating comparable PK profiles between groups. In addition, the PASI, Dermatology Life Quality Index, and static Physician’s Global Assessment efficacy scores were highly similar for both treatment groups. There were no clinically meaningful differences between the immunogenicity and safety assessments of repeated switching between AVT02 and the reference product, versus the reference product alone.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the risk, in terms of safety or diminished efficacy of switching between the biosimilar and the reference product, is not greater than the risk of using the reference product alone, as required by the FDA for interchangeability designation. Beyond the scope of interchangeability, a consistent long-term safety and immunogenicity profile, with no impact on the trough levels up to 52 weeks, was established.

Clinical Trial Registration

NCT04453137; date of registration: 1 July 2020

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The PK profiles were comparable between the switching and non-switching groups, as demonstrated by the 90% CIs of arithmetic means ratio for primary endpoints, AUCtau, W26–28 and Cmax, W26–28 being within the prespecified limits of 80–125%. |

This study demonstrates that the risk, in terms of safety or diminished efficacy of switching between the AVT02 and the reference product, is not greater than the risk of using the reference product alone. |

The results of this clinical study support the interchangeability of AVT02 with Humira. |

Long-term safety and immunogenicity data collected during the optional extension phase add to the knowledge base for AVT02. |

1 Introduction

Demonstrating the interchangeability of biosimilars with reference products supports clinical practice by reducing costs and increasing patient access to often-expensive biologic therapies [1]. Switching from a reference product to a biosimilar does not cause loss of efficacy, and no increased rates of side effects or immunogenicity [2, 3]. As biosimilars are being developed, interchangeability study results continue to build confidence in biosimilars and increasing use. In accordance with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) interchangeability guidelines, the primary endpoint in a switching study should assess the impact of switching or alternating between the proposed interchangeable product and the reference product on clinical pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (if available) [4]. These assessments are most likely to be sensitive to changes in immunogenicity and/or exposure that may arise as a result of alternating or switching treatment [4]. Interchangeability of the reference product with a biosimilar requires additional criteria to be met, such as producing the same clinical result as the reference product in any given patient. Regulations state that an interchangeable product may be substituted for the reference product without the involvement of the prescriber. Interchangeability without prescriber involvement also applies to any batch-to-batch variation of the biosimilar that often occurs with biologics that are too large to duplicate [5].

Plaque psoriasis is an inflammatory, T-cell-mediated condition that typically manifests as sharply demarcated chronic erythematous plaques covered by thick, silvery-white scales [6]. Local production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), in conjunction with resident T cells, contributes to chronic inflammation in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, affecting the function of many different cell types in psoriatic skin [6]. This is likely a reflection of the central role of TNF-α in regulation of the proinflammatory cytokine cascade and local T-cell proliferation and function [7].

Adalimumab (reference product Humira®, ATC code L04AB04) is an anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody globally approved for various indications, including psoriasis [8, 9]. AVT02 has been developed to be biosimilar to reference product. AVT02 is a recombinant, fully human monoclonal immunoglobulin G1 antibody that binds specifically and with high affinity, similarly to reference product, to the soluble and transmembrane forms of TNF-α. Although both high (100 mg/mL) and low (50 mg/mL) concentrations have been approved for the reference product, over 80% of Humira prescriptions are for the high-concentration preparation in the USA [10]. AVT02 is being developed as a high-concentration (100 mg/mL) preparation. The 100 mg/mL preparation is considered to have an advantage over the 50 mg/mL preparation; its higher dose and lower volume is more patient friendly with less injection site-related pain [11]. AVT02, as a biosimilar to the reference product, has demonstrated similar PK, efficacy, and safety [12,13,14,15]. The aim of this study was to investigate the PK, antibody presence, efficacy, and safety in participants undergoing repeated switches between reference product and AVT02 to demonstrate interchangeability.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design and Participant Population

This was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study conducted at 23 study centers across five countries (Georgia, Iceland, Poland, Russia, and Ukraine). Eligible participants had moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis with involved body surface area ≥ 10% (Palm Method), a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score ≥ 12, a static Physician’s Global Assessment (sPGA) ≥ 3 (moderate to severe) at screening and at baseline (week 1/day 1), and naïve to adalimumab therapy. A negative QuantiFERON test for tuberculosis was required during screening. Exclusion criteria included: participants diagnosed with erythrodermic psoriasis; pustular psoriasis; guttate psoriasis; medication-induced psoriasis; other skin conditions (e.g., eczema); or other systemic autoimmune disorder inflammatory diseases. The study design comprised: a lead-in period during weeks 1–12 (open‑label treatment), a module with switching arm (three switching periods) and a non-switching arm during weeks 12–28 (double‑blind treatment), followed by an optional open-label phase extension during weeks 28–52 (open‑label treatment if completed the lead-in period and switching period) (Fig. 1).

During scheduled clinic visits, participants underwent several evaluations and assessments including vital signs, electrocardiograms, clinical laboratory tests, body surface area, PASI, sPGA, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), immunogenicity, PK analysis, and assessment of adverse events (AEs). Participants provided written informed consent before participation in this study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) guidelines and the appropriate regulatory requirements in the countries in which the study was conducted.

2.2 Study Treatment

During the lead-in period (open label; treatment given from week 1 to 12), participants initially received 80 mg of reference product [2 × 40 mg subcutaneous (SC) injections] on week 1/day 1. This was followed by a single 40 mg SC injection of reference product every other week (EOW) from week 2 to 12 with doses given at weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10) (Fig. 1). Study treatment was administered by the site investigator at each study visit during the lead-in period. At the end of the lead-in period, participants with a clinical response of ≥ 75% improvement in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI75) were permitted to enter the switching module and randomly assigned (1:1) to one of two treatment groups. In group 1 for the first switching period, participants received a single 40 mg SC injection of AVT02 EOW (i.e., doses at weeks 12 and 14); for the second switching period, participants received a single 40 mg SC injection of reference product EOW (i.e., doses at weeks 16 and 18); for the third switching period, participants received a single 40 mg SC injection of AVT02 EOW (i.e., doses at weeks 20, 22, 24, and 26). For treatment group 2, participants received a single 40 mg SC injection of reference product EOW from week 12 to 26 (i.e., doses at weeks 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, and 26). During the switching module (weeks 12–28), study treatment was administered at each study visit by the site investigator (i.e., weeks 12, 16, 20, and 26); the participant/caregiver administered the study treatment at home, with optional administration on site if required on weeks 14, 18, 22, and 24. At week 28, participants with a clinical response (PASI50) were offered the possibility of continuing in the optional extension phase of the study (weeks 28–52). In the extension phase, a single 40 mg SC injection of AVT02 was administered EOW starting from week 28, ending with the final study treatment administration at week 50 (i.e., doses at weeks 28, 30, 32, 34, 36, 38, 40, 42, 44, 46, 48, and 50). Except for doses at weeks 28 and 42, when study treatment was administered at the study visit by the site investigator, the participant/caregiver administered remaining doses at home (i.e., doses at weeks 30, 32, 34, 36, 38, 40, 44, 46, 48, and 50). The end of study visit was at week 52.

Patients were encouraged not to miss study drug doses, and a window of ± 3 days was allowed for the dosing schedule. Patients/caregivers were instructed to inject study drug at approximately the same time and day every other week. Study drug was dispensed in single-use, prefilled syringes. Subjects/caregivers were instructed for handling of the study drug and trained to utilize an eDiary to collect information about the injections and any possible injection site reactions (ISRs). The study staff helped the subject/caregiver register into the eDiary system at the time of the first dosing visit. Study staff and subjects were notified if the subject/caregiver did not enter information into the eDiary system ± 3 days of the expected date/time of a dose. The subject/caregiver received a telephone call from the study site to enquire whether the dose of study drug was given and/or any AEs have occurred. At each visit, study staff reviewed the eDiary entries with the subject/caregiver and provided re-training, as necessary. Study drug compliance per protocol in this study was assessed by the investigator and study staff on the basis of the study drug usage recorded by the subject/caregiver in the eDiary. For participants for whom there were compliance issues, participants/caregivers were re-educated by the investigator or study staff on the importance of administering study drug per protocol.

In this study, AVT02 and reference product were administered per the approved dosing regimen for moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis (40 mg/mL). Blinding during the switching module (double blind) was achieved by masking devices to conceal the syringes. During the lead-in period, all participants received the reference product. At week 12, if participants met the PASI75 qualification for the switching module, the site contacted the interactive response technology to randomize the participant to the treatment arms. Participants were assigned to the study drug in accordance with the randomization schedule generated using permuted block randomization by an independent statistician. Participant randomization was stratified by body mass index (BMI) (< 30 kg/m2 or ≥ 30 kg/m2), and age (< 65 years or ≥ 65 years).

2.3 Primary Outcomes

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the PK in participants receiving only reference product compared with the PK in participants undergoing repeated switches between reference product and AVT02 using the endpoints: area under the concentration–time curve over the dosing interval (AUCtau) from week 26 to 28 (AUCtau, W26–28), and maximum concentration (Cmax) over the dosing interval from week 26 to 28 (Cmax, W26–28). Secondary PK endpoints included: time to maximum concentration during the dosing interval from week 26 to 28; trough concentration (Ctrough) over the dosing interval from week 26 to 28; Ctrough after each switch at weeks 12, 16, and 20; ratio of Ctrough after the last administration of the study drug at week 26 versus week 12; Ctrough after the last administration of the study drug at week 26 in participants who were PASI75 responders; and percentage of anti-drug antibody (ADA)-negative participants at week 12.

2.4 Other Evaluations

Secondary objectives compared the immunogenicity, efficacy, and safety profiles of reference product with repeated switching of reference product and AVT02. Immunogenicity was evaluated using a one-assay approach to detect anti-AVT02 and anti-reference product (Humira) antibodies in one assay setup following current recommendations [16]. Serum samples for immunogenicity assessment were collected at weeks 1 (baseline), 12, 16, 20, 26, and 28 during the switching module and at weeks 42 and 52 during the optional extension phase. Efficacy endpoints were percentage improvement in PASI from week 1 to 28 and percentage improvement in PASI from week 12 to 28. During analysis, absolute improvement was also included as this was deemed a more clinically relevant endpoint. Change in DLQI was assessed from week 1 to 28 and week 12 to 28. The number and percentage of participants who achieved sPGA responses of clear (0) or almost clear (1) at weeks 12 and 28 were recorded. Only participants with PASI ≥ 50% were allowed to continue into the optional extension phase. Safety assessments included analysis of incidence, type, and severity of AEs (including adverse drug reactions), injection-site reactions (ISRs), ADAs, physical examination, and laboratory parameters (routine safety parameters, liver function parameters, serology screening test, QuantiFERON-TB Gold test). A complete physical examination consisted of general, head, eyes, ears, nose, throat, respiratory, gastrointestinal, extremity, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, nervous system, lymph node, and dermatologic evaluations and height, weight, and any other physical conditions of note. A targeted physical examination consisted of vital signs and evaluations of skin and joints and cardiovascular, respiratory, neurologic, and any other systems associated with the participant’s complaints or AEs. Participants recorded any ISRs in the eDiary and on the paper ISR worksheet provided. Participants described the characteristics of the ISR (e.g., pain/tenderness, erythema/redness, induration/swelling, pruritus/itching, hematoma/ecchymosis/bruising) at the site of injection. Any findings were recorded on the ISR worksheet, and if the intensity grading was ≥ 1, were entered into the electronic case report form as an AE. AEs were reported from the lead-in period to the end of the optional extension phase of the study.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoints AUCtau, W26–28 and Cmax, W26–28 were analyzed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model, with the treatment group as a fixed effect and age and BMI at week 12 as the continuous covariates, to estimate the arithmetic least square (LS) means for each treatment group and the corresponding standard errors (SE). The analysis of the primary endpoints involved calculating the 90% confidence intervals (CIs) for the arithmetic means ratios, which were constructed using the Fieller’s theorem [17]. Arithmetic means were used in preference to geometric means due to the lack of normality for both AUCtau, W26–28 and Cmax, W26–28 on the natural log scale. Normality was satisfied, however, on the untransformed scale. A conclusion of equivalence was made on the basis of the 90% CIs being within the range 80–125% for the per protocol set for both AUCtau, W26–28 and Cmax, W26–28. Additionally, the arithmetic means ratios and associated 90% CIs are presented for the full analysis set (FAS), the per protocol set, and the subgroups defined according to the following: coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination status, age, gender, BMI at week 12, ADA status, and neutralizing antibody (NAb) status.

In addition, descriptive statistics of AUCtau, W26–28 and Cmax, W26–28, percentage improvement in PASI, and change in DLQI and sPGA were further evaluated by treatment group for selected subgroups of the FAS. Descriptive statistics for Ctrough at weeks 12, 16, and 20 were provided by treatment group on the basis of observed data for the FAS. Moreover, the same model as for the primary analysis (ANCOVA) was provided for the evaluation of Ctrough after each switch on the basis of the observed data for the FAS.

Sample size was determined to ensure a sufficient number of participants were available for the primary endpoint analysis. Assuming that 71.5% of participants initially recruited would be PASI75 responders at week 12 [18] and assuming an 18% non-evaluable rate among the PASI75 responders (due to dropouts and those not providing data at week 26), 550 participants were planned to participate in the study at week 1 (baseline).

3 Results

3.1 Participant Disposition

The demographics and baseline characteristics were well balanced across both treatment groups (Table 1, Online Resource 1) with a total of 698 screened participants of which 131 were screen failures (Fig. 2). During the lead-in period (weeks 1–12), all enrolled participants (567) received reference product; nine (1.9%) discontinued study treatment during the lead-in period. Overall, 550 participants (97.0%) had clinical responses of PASI75 at week 12 and entered the switching module. Eight participants (1.4%) completed the lead-in period but did not have PASI75 clinical responses. During the switching module (weeks 12–28), 277 participants were randomized to the AVT02/reference product/AVT02 group, and 273 were randomized to the reference product-only group. Twenty-two participants (4.0%) discontinued study treatment during the switching module [14 (5.1%) in the switching group and 8 (2.9%) in the non-switching group] (Table 2). Overall, 525 participants (92.6%) had a clinical response of PASI ≥ 50% at week 28 and entered the optional extension phase of the study. Most participants (514; 97.9%) completed the extension phase, with 11 (2.1%) discontinuing treatment. Adverse effects not related to COVID-19 were the most common reasons for treatment discontinuation (Table 2).

Disposition of participants. aCOVID-19 related n = 0; not COVID-19 related n = 3. bCOVID-19 related n = 0; not COVID-19 related n = 4. cCOVID-19 related n = 1; not COVID-19 related n = 6. dCOVID-19 related n = 0; not COVID-19 related n = 4. eCOVID-19 related n = 1; not COVID-19 related n = 2. fCOVID-19 related n = 0; not COVID-19 related n = 4. gCOVID-19 related n = 1; not COVID-19 related n = 4. hCOVID-19 related n = 0; not COVID-19 related n = 5. n number of participants in the sample, PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index

3.2 Primary Endpoint: Pharmacokinetics

The LS mean of AUCtau, W26–28 for the switching and non-switching groups was 3.15 × 106 and 3.10 × 106, respectively (Table 3). The ratio of the LS means (90% CI) was 101.7 (91.4–112.0). The LS mean of Cmax, W26–28 for the switching and non-switching groups was 1.40 × 104 and 1.29 × 104, respectively (Table 3). The ratio of the LS means (90% CI) was 108.1 (98.3–117.9). The 90% CIs for the switching:non-switching LS mean ratio for both AUCtau, W26–28 and Cmax, W26–28 were within the limits of 80–125%, demonstrating PK similarity between the switching and non-switching treatment groups (Table 3). Arithmetic means ratios and 90% confidence intervals for the primary endpoints AUCtau, W26–28 and Cmax, W26–28 for subgroups were similar (Fig. 3).

Forest plot (Fieller’s theorem) of 90% CI for ratio of arithmetic mean: (A) AUCtau and (B) Cmax, from week 26 to 28—switching module (weeks 12–28). ADA anti-drug antibody, AUCtau, W26–28 area under the concentration–time curve over the dosing interval from week 26 to 28, BMI body mass index, CI confidence interval, Cmax, W26–28 maximum concentration over the dosing interval from weeks 26–28, COVID-19 coronavirus 2019, FAS full analysis set, NAb neutralizing antibody

Secondary PK endpoints indicated trough (predose) concentrations of adalimumab were in the similar range for individual participants with repeated switches between week 16 and week 28 (switching group) compared with the consistent dosing regimen of the non-switching group (Fig. 4). During the weeks 26–28 dosing interval, the mean adalimumab concentrations and mean concentration–time profiles were similar for both treatment groups (Fig. 5).

Adalimumab trough concentrations for individual participants after switching and non-switching from week 1 through week 28—per protocol set. Although one participant (reference product group) was considered an outlier during the week 26–28 dosing interval, data for subject 7001025 were considered evaluable during the lead-in period and were retained in the trough concentration figures

Mean (SD) adalimumab concentration-time profiles after switching and non-switching from week 26 through week 28—per protocol set (excluding one participant). Subject 7001025 (reference product group) was considered an outlier during the week 26–28 dosing interval; data for subject 7001025 were excluded from this figure. SD standard deviation

Considering the high intersubject variability (up to 92.0%), overall, the mean trough concentration (Ctrough) was similar between the switching and non-switching treatment groups, increasing slightly for both treatment groups with each subsequent administration between week 10 and week 26 (Table 4). The mean Ctrough ranged from 6498.6 to 7459.6 ng/mL in the switching group and from 6250.5 to 7364.8 ng/mL in the non-switching group. The ratio of Ctrough for weeks 26–28 and weeks 10–12 was 1.0 for the repeated switches in the switching group and 1.1 in the non-switching treatment group, suggesting no appreciable accumulation. The arithmetic LS mean Ctrough ratios ranged from 99.9% to 106.3% and the 90% CIs were within the 80–125% range for concluding equivalence. These results were confirmed using a bootstrapping method, which yielded comparable 90% CIs.

3.3 Secondary Endpoints

3.3.1 Immunogenicity

Most participants were ADA positive in the lead-in period [398 (70.2%) of which 318 had NAbs] and the switching period (switching group: 86.3%; non-switching group: 87.9%), which included 14.4% who were already positive at baseline (Fig. 6). The presence of drug reactive, pre-existing antibodies has been observed in other clinical studies with Humira biosimilars such as Hyrimoz (GP2017) [19], Cyltezo (BI 695501) [20], and Amjevita (ABP 501) [21, 22], as well as in AVT02 [12]. The exact cause of this is often unknown but could be a consequence of prior exposure to a protein or glycan with a similar epitope [23]. Through week 12, the incidence of treatment-emergent ADAs was 66.0%; 82.0% of ADA-positive participants also had NAbs (Online Resource 2). During the switching period, the percentage of participants who were ADA or NAb positive was similar in the switching and non-switching treatment groups (Fig. 6). Through week 28, the total incidence of ADA was 86.3% in the switching group and 87.9% in the non-switching group. The prevalence of ADAs and NAbs (in participants with ADAs) was comparable at all timepoints assessed in the switching module, including at both week 26 and week 28, the timepoints covering the primary endpoint. From week 12 to 28, the incidence of treatment-emergent ADAs was 57.5% in the switching group compared with 57.1% in the non-switching group; a similar percentage of participants with ADAs had NAbs (79.5% versus 82.3%, respectively). During the optional extension phase, the total incidence of ADAs was 90.3% and the total incidence of NAbs was 82.7% (Online Resource 3). ADAs and NAbs (in participants with ADAs) were comparable at all timepoints assessed in the optional extension phase, including at both week 42 and week 52. From week 28 to 52, the incidence of treatment-emergent ADAs was 25.0%. Antibody incidence before the optional extension phase was 66.7% and 55.2% for ADAs and NAbs, respectively.

During the lead-in period, the median ADA titer was, as expected, higher at week 12 (32.0) compared with baseline (2.0). During the switching period, the median ADA titer was comparable across timepoints (baseline and weeks 12, 16, 20, 26, and 28) in both the switching and non-switching arms (Fig. 7). The time of onset and frequencies of ADAs and NAbs were similar in participants in the switching and non-switching treatment groups through week 28. Caution should be used when analyzing the semi-quantitative ADA titer data using summary statistics, which are typically used for continuous variables. The similar titer between treatment groups is reflected in the comparable ADA and NAb incidence rates at week 26 and week 28 (the window for the primary endpoint) in the switching module. In the optional extension phase, the ADA titer levels were similar across weeks 28, 42, and 52.

3.3.2 Efficacy

The mean absolute PASI values and the mean percentage PASI improvement from baseline to week 28 were similar in the switching group (from 23.6 to 0.9; 96.0% improvement) and the non-switching treatment group (from 23.3 to 0.9; 95.8% improvement) (Online Resource 4 and 5). At week 28, the absolute improvement from baseline in PASI was similar in both treatment groups [22.96 (mean standard deviation, SD 8.42) in the switching group and 22.33 (mean SD 8.19) in the non-switching group] with a treatment difference (95% CI) of 0.63 (− 0.79 to 2.05). At week 28, the absolute improvement from week 12 in PASI was not clinically significant in the switching group compared with the non-switching group [0.37 (1.84) versus 0.22 (2.26)] with a treatment difference (95% CI) of 0.16 (– 0.2 to 0.51) (Online Resource 4). Both the mean absolute PASI value and the mean percentage PASI improvement by ADA status from baseline to week 12 were similar for both the switching and non-switching groups in the ADA-positive subgroup [from 23.7 to 1.3 (a 94.2% improvement) and from 23.7 to 1.2 (a 94.4% improvement), respectively] and in the ADA-negative subgroup [from 23.4 to 1.1 (a 95.4% improvement) and from 20.7 to 0.9 (a 95.7% improvement), respectively]. This efficacy persisted and improved from baseline through week 28 in both the switching and non-switching groups in the ADA-positive and ADA-negative subgroups (Fig. 8D–F).

Efficacy data in those with or without neutralizing antibodies (NAbs): (A) absolute change in PASI score, (B) absolute change in DLQI score, (C) percentage achieving static physician’s global assessment responses of clear (0) or almost clear (1), and those with or without antidrug antibodies (ADAs): (D) absolute change in PASI score, (E) absolute change in DLQI score, (F) percentage achieving static physician’s global assessment responses of clear (0) or almost clear (1), during the switching module. ADA anti-drug antibody, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, NAb neutralizing antibody, PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, sPGA static Physician’s Global Assessment

From baseline to week 28, mean (SD) DLQI score in the switching group improved from 14.4 (6.87) to 1.6 (2.88), with a mean change of – 12.9 (7.25). During the same time period, the mean (SD) DLQI score in the non-switching group improved from 14.5 (6.69) to 1.9 (3.36). From week 12 to 28, mean (SD) DLQI score in the switching group improved from 2.0 (3.11) to 1.6 (2.88); a similar trend was seen in the non-switching treatment group, from 2.3 (3.47) to 1.9 (3.36) (Online Resource 6). The mean (SD) change from baseline to week 28 in DLQI by ADA status was − 13.0 (7.33) in the switching group and − 12.8 (7.57) in the non-switching group in the ADA-positive subgroup and − 12.3 (6.80) versus − 11.1 (6.51), respectively, in the ADA-negative subgroup (Fig. 8E).

At week 12, the total percentage of participants achieving sPGA responses of clear (0) or almost clear (1) at week 12 was 94.8% (n = 527/556) (Fig. 8C), accounting for 95.3% (n = 264/277) in the switching treatment group and 96.0% (n = 262/273) in the non-switching treatment group. At week 28, the percentage of participants with sPGA responses of clear (0) or almost clear (1) was: 92.0% (n = 242/263) in the switching group and 91.7% (n = 242/264) in the non-switching group (Fig. 8C). The percentage change in PASI, DLQI, and sPGA was comparable between participants with or without ADAs or NAbs (Fig. 8). There were no meaningful differences in efficacy outcomes for switching group compared with the non-switching group in the switching module.

3.3.3 Safety

The majority of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) reported were mild. The number and percentage of participants with any TEAEs were similar in both groups: non-switching group 90 (33%) participants with 188 events; switching group 86 (31%) participants with 168 events, from week 12 to 28 (Table 5). In the optional extension phase, most TEAEs were mild [126 TEAEs in 82 participants (15.6%)], four participants (0.8%) experienced five severe TEAEs, and 123 participants (23.4%) reported a total of 200 TEAEs (Online Resource 7). In both treatment groups, the most commonly reported TEAE during the switching period was ISRs (Online Resource 8). Most were mild or moderate in severity. During the switching period, 150 treatment-related TEAEs occurred in 81 participants (14.7%): 42 participants (15.4%, 94 events) in the non-switching group; 39 participants (14.1%, 56 events) in the switching group. During the switching module, six participants (1.1%) reported six serious TEAEs; none of these was considered treatment related (Online Resource 9). During the optional extension phase, three participants (0.6%) reported three serious TEAEs, of which one (erysipelas) was considered treatment related. The erysipelas occurred on the right leg, for which the subject was hospitalized and treated with penicillin. The intensity of the event was reported by the investigator as moderate and study treatment was not interrupted due to the event. Overall, there were no notable differences in severe treatment-related TEAEs between the treatment groups. One participant died during the study, due to carbon monoxide poisoning (not related to study treatment). No clinically significant changes from baseline over time were observed across the treatment groups in any hematology, chemistry, urinalysis, vital signs, physical examinations, or electrocardiogram values (Online Resource 10).

4 Discussion

Biosimilars are rapidly being developed as alternatives to expensive reference biologics and have been reducing financial pressures facing healthcare systems [1, 24, 25]. In the USA, interchangeability may be important to achieve maximal savings, as interchangeability would permit pharmacy-level auto-substitution of an innovator product [26]. Our study was conducted in accordance with FDA interchangeability regulatory guidelines, and the PK were comparable for the switching and non-switching groups. All PK parameters of relevance [mean Ctrough (Ctrough, W10–12 through Ctrough, W26–28), mean AUCtau, W26–28 and Cmax, W26–28] were similar for the FAS of the switching and non-switching groups. Different participant subgroups were evaluated in terms of the mean AUCtau and Cmax from week 26 to 28, and the results were similar between the treatment groups with minor differences in the age, gender, and BMI subgroups, which were not statistically significant and can be attributed to the small sample size. In addition, serum concentrations of adalimumab were similar for individual participants with the repeated switches in the switching group and the non-switching group, suggesting that the efficacy of AVT02, as with other biosimilars, is maintained over time [12, 20, 27,28,29,30]. This switching study corroborates the lack of clinically meaningful differences between AVT02 (100 mg/mL) and reference product, thus supporting the idea of interchangeability.

The higher clinical response rate (97% of patients achieved PASI75 at week 12) in this study than could be anticipated could be attributed to strict adherence to the protocol and comprehensive training on recording of PASI scores during site visits, although there is a known subjectivity with the PASI score method. Furthermore, there were more participants in this study who had “severe” rather than “moderate” chronic plaque psoriasis and were thus more responsive to adalimumab. Finally, participants in our study had a lower BMI on average than in previous adalimumab studies, suggesting higher efficacy [31, 32].

A challenge with biologic therapeutics is the possibility of varied immunogenicity; however, the similarity in percentage change in PASI and DLQI, and participants with consistent sPGA scores across ADA-/NAb-negative and ADA-/NAb-positive groups showed no meaningful difference in immunogenicity between reference product and AVT02. The safety profile observed for this study was consistent with the profile of both reference product and AVT02. In addition, there were no clinically meaningful differences or unexpected observations between switching and non-switching arms in terms of serious TEAEs, treatment-related TEAEs leading to discontinuation, and TEAEs of special interest. In this study, only one serious TEAE (erysipelas) was considered treatment related, occurring during the optional extension phase. Since PK, immunogenicity, and safety profiles were maintained throughout the study, sustained efficacy during the extension phase can be expected, supporting the switching between reference product and AVT02.

5 Conclusion

AVT02 has similar structure, PK, and target binding to reference product. Therefore, it is not surprising that there was no clinically meaningful difference in efficacy, safety, or immunogenicity between using reference product or switching between AVT02 and reference product. On the basis of the PK similarity, similar efficacy endpoints, and comparable AE and ADA/NAb profiles between the switching and non-switching arms, AVT02 and the reference product (high-concentration Humira) meet the FDA requirements for interchangeable status.

References

Barbier L, Vulto AG. Interchangeability of biosimilars: overcoming the final hurdles. Drugs. 2021;81:1897–903. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-021-01629-4.

Barbier L, Ebbers HC, Declerck P, Simoens S, Vulto A, Huys I. The efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of switching between reference biopharmaceuticals and biosimilars: a systematic review. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;108:734–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.1836.

Kurki P, Barry S, Bourges I, Tsantili P, Wolff-Holz E. Safety, immunogenicity and interchangeability of biosimilar monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins: a regulatory perspective. Drugs. 2021;81:1881–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-021-01601-2.

Considerations in demonstrating interchangeability with a reference product: guidance for industry. In: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER). 2019. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/considerations-demonstrating-interchangeability-reference-product-guidance-industry. Accessed 13 September 2022.

Patel PK, King CR, Feldman SR. Biologics and biosimilars. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:299–302. https://doi.org/10.3109/09546634.2015.1054782.

Schön MP, Boehncke WH. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1899–912. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra041320.

Herrier RN. Advances in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68:795–806. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp100227.

Humira, Summary of Product Characteristics. Ludwigshafen, Germany: AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG. 2021. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/humira-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 13 September 2022.

Humira, Prescribing Information. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc. 2021. https://www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/humira.pdf. Accessed 13 September 2022.

Jeremias S. FDA accepts biologics license applications supporting interchangeability from Alvotech, Pfizer for biosimilars to Humira. In: The Accreditation Council for Medical Affairs, The Center for Biosimilars. 2022. https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/fda-accepts-bla-supporting-interchangeability-for-alvotech-s-high-concentration-biosimilar-for-humira. Accessed 13 September 2022.

Nash P, Vanhoof J, Hall S, et al. Randomized crossover comparison of injection site pain with 40 mg/0.4 or 0.8 ml formulations of adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2016;3:257–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-016-0041-3.

Feldman SR, Reznichenko N, Pulka G, et al. Efficacy, Safety and immunogenicity of AVT02 versus originator adalimumab in subjects with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, parallel group, active control, phase iii study. BioDrugs. 2021;35:735–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-021-00502-w.

Damjanov N, Kirvalidze N, Kurashvili N, Berti F, Steiger M, Sobierska J, Guenzi E, Otto H, Sattar A, Haliduola HN, Edwald E, Stroissnig H. Assessment of real-life patient handling experience of AVT02 administered subcutaneously via autoinjector in patients with moderate to severe active rheumatoid arthritis: an open-label, single-arm clinical trial, then an extension phase of AVT02 administered with a prefilled syringe. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/14712598.2022.2131392.

Wynne C, Schwabe C, Stroissnig H, Dias R, Sobierska J, Guenzi E, Otto H, Sattar A, Haliduola HN, Edwald E, Berti F. A multicenter, randomized, open-label, 2-arm parallel study to compare the pharmacokinetics, safety and tolerability of AVT02 administered subcutaneously via prefilled syringe or autoinjector in healthy adults. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/14712598.2022.2131391.

Wynne C, Schwabe C, Lemech C, Stroissnig H, Dias R, Sobierska J, Guenzi E, Otto H, Sattar A, Kay R, Haliduola HN, Berti F. A randomized, adaptive design, double-blind, 3-arm, parallel study assessing the pharmacokinetics and safety of AVT02, a high-concentration (100 mg/mL) Adalimumab biosimilar, in healthy adult patients (ALVOPAD FIRST). Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2022;2:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13543784.2022.2035359.

Civoli F, Kasinath A, Cai XY, et al. Recommendations for the development and validation of immunogenicity assays in support of biosimilar programs. AAPS J. 2020;22:7. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-019-0386-y.

Fieller EC. Some problems in interval estimation. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc, Series B. 1954;16:175–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1954.tb00159.x.

Saurat J-H, Stingl G, Dubertret L, Papp K, Langley RG, Ortonne J-P, Unnebrink K, Kaul M, Camez A. Efficacy and safety results from the randomized controlled comparative study of adalimumab vs. methotrexate vs. placebo in patients with psoriasis (CHAMPION). Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:558–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08315.x.

Von Richter O, Lemke L, Haliduola H, et al. GP2017, an adalimumab biosimilar: pharmacokinetic similarity to its reference medicine and pharmacokinetics comparison of different administration methods. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:1075–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/14712598.2019.1571580.

Cohen SB, Alonso-Ruiz A, Klimiuk PA, Lee EC, Peter N, Sonderegger I, Assudani D. Similar efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of adalimumab biosimilar BI 695501 and Humira reference product in patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis: results from the phase III randomised VOLTAIRE-RA equivalence study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:914–21. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212245.

Papp K, Bachelez H, Costanzo A, et al. Clinical similarity of the biosimilar ABP 501 compared with adalimumab after single transition: long-term results from a randomized controlled, double-blind, 52-week, phase III trial in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1562–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15857.

Cohen S, Genovese MC, Choy E, et al. Efficacy and safety of the biosimilar ABP 501 compared with adalimumab in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, phase III equivalence study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1679–87. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210459.

Gorovits B. Pre-existing antibody: biotherapeutic modality-based review. AAPS J. 2016;18:311–20. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-016-9878-1.

Wiland P, Jeka S, Dokoupilová E, Brandt-Jürgens J, Miranda Limón JM, Cantalejo Moreira M, Cabello RV, Jauch-Lembach J, Thakur A, Haliduola H, Brueckmann I, Gaylis NB. Switching to biosimilar SDZ-ADL in patients with moderate-to-severe active rheumatoid arthritis: 48-week efficacy, safety and immunogenicity results from the phase iii, randomized, double-blind ADMYRA study. BioDrugs. 2020;34:809–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-020-00447-6.

Jensen TB, Kim SC, Jimenez-Solem E, Bartels D, Christensen HR, Andersen JT. Shift from adalimumab originator to biosimilars in Denmark. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:902–3. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0338.

Afzali A, Furtner D, Melsheimer R, Molloy P. The automatic substitution of biosimilars: definitions of interchangeability are not interchangeable. Adv Ther. 2021;38:155–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01688-9.

Takahashi H, Tsuji H, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Iizuka H. Plasma trough levels of adalimumab and infliximab in terms of clinical efficacy during the treatment of psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:39–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01679.x.

Pouw MF, Krieckaert CL, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Key findings towards optimising adalimumab treatment: the concentration–effect curve. Ann Rheum. 2015;74:513–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204172.

Cohen S, Pablos JL, Pavelka K, Müller GA, Matsumoto A, Kivitz A, et al. An open-label extension study to demonstrate long-term safety and efficacy of ABP 501 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-019-1857-3.

Genovese MC, Kellner H, Arai Y, et al. Long-term safety, immunogenicity and efficacy comparing FKB327 with the adalimumab reference product in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: data from randomised double-blind and open-label extension studies. RMD Open. 2020;6: e000987. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2019-000987.

Gordon KB, Langley RG, Leonardi C, et al. Clinical response to adalimumab treatment in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: double-blind, randomized controlled trial and open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(4):598–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.027.

Menter A, Tyring SK, Gordon K, et al. Adalimumab therapy for moderate to severe psoriasis: a randomized, controlled phase III trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(1):106–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2007.09.010.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who participated in the study and all the investigators who contributed, as well as Lorna Rettig and Shital Desai of Alvotech for assistance with clinical data. The authors also thank Lucretia Ramnath, of Nucleus Global, UK, for providing editorial support, which was funded by Alvotech in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines (https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M22-1460).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The study was sponsored by Alvotech Swiss AG. Employees of the sponsor had a role in study design, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. Employees of the funder had no role in data collection.

Competing interests

SRF has received research grants from AbbVie, Janssen, Lilly, and Novartis and speaker honoraria from Alvotech, AbbVie, Amgen, Lilly, Novartis, and Janssen. RK’s company has received consultancy fees in relation to this study and in other studies conducted by Alvotech, but no consultancy fees have been received in relation to the writing of this manuscript. NR declares that she has no conflicts of interest that might be relevant to this work. RD, HO, HNH, AS, RR, HS, and FB are employees at Alvotech. JS was an employee of Alvotech at the time of the study.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) guidelines, and the appropriate regulatory requirements in the countries in which the study was conducted. The protocol, its amendments, and informed consent documentation were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board(s) or independent ethics committee(s) at each study site.

Consent to participate

All participants signed an Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee-approved informed consent form before any study-specific procedures were performed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Author contributions

SRF, RK, HS, FB, HNH, AS, JS, and HO were involved in the conception and design of the study. NR, RD, and RR were involved in the provision of study materials and participants and acquisition of the data. SRF, RK, HS, FB, HNH, AS, JS, and HO did the analysis and/or the interpretation of the data. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feldman, S.R., Kay, R., Reznichenko, N. et al. Assessing the Interchangeability of AVT02 and Humira® in Participants with Moderate‑to‑Severe Chronic Plaque Psoriasis: Pharmacokinetics, Efficacy, Safety, and Immunogenicity Results from a Multicenter, Double-Blind, Randomized, Parallel-Group Study. BioDrugs 37, 551–567 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-023-00600-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-023-00600-x