Abstract

Several advanced alloy systems are susceptible to weld solidification cracking. One example is nickel-based superalloys, which are commonly used in critical applications such as aerospace engines and nuclear power plants. Weld solidification cracking is often expensive to repair, and if not repaired, can lead to catastrophic failure. This study, presented in three papers, presents an approach for simulating weld solidification cracking applicable to large-scale components. The results from finite element simulation of welding are post-processed and combined with models of metallurgy, as well as the behavior of the liquid film between the grain boundaries, in order to estimate the risk of crack initiation. The first paper in this study describes the crack criterion for crack initiation in a grain boundary liquid film. The second paper describes the model required to compute the pressure and thickness of the liquid film required in the crack criterion. The third and final paper describes the application of the model to Varestraint tests of alloy 718. The derived model can fairly well predict crack locations, crack orientations, and crack widths for the Varestraint tests. The importance of liquid permeability and strain localization for the predicted crack susceptibility in Varestraint tests is shown.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Weld hot cracking can be difficult to avoid when welding of certain alloys such as nickel-based superalloys [1, 2]. The crack can be small and is therefore difficult to detect by non-destructive test methods. It can act as an initiation site for fatigue and corrosion cracking [3], which can be expensive to repair. The formation of the crack depends on the welding process, e.g., changes in weld heat input, welding speed, and external restraints from fixturing can all influence the crack susceptibility [1, 4]. Numerical simulation can be a powerful tool for reducing the risk of cracking. It can be used in the early stage of the design of a welding process to optimize process parameters such that the crack susceptibility can be minimized.

Weld hot cracking has been extensively studied for more than 60 years. Most of that work has been focused on experimental studies and not so much on numerical modeling. However, there are a number of interesting publications on numerical modeling of weld hot cracking. For example, Feng simulated a solidification centerline cracking in aluminum alloy 2024 [5]. Cracking was considered as a result of the competition between the material’s resistance to cracking and the mechanical driving force for cracking. The material’s resistance to cracking was given by a ductility curve in the solidification temperature interval. The ductility curve was constructed from a weldability test, while the mechanical driving force for cracking was given by the transverse mechanical strains on the weld centerline, obtained from a FE model of the welding process where the heat source was modeled by a radially symmetric Gaussian distribution. Cracking was assumed to occur if the mechanical strain in the solidification interval is larger than the ductility strain at the corresponding temperature.

Ploshikhin et al. simulated a solidification centerline cracking in aluminum alloy AA6056 [6]. They emphasized the importance of deformation localization in intergranular liquid films on the crack sensitivity. They could estimate up to 1000% of strain in a liquid film located at the weld centerline. Cracking was considered to occur when the deformation of the solidified alloy at the centerline exceeded a critical value. This critical value was determined by a weldability test. The deformation at the weld centerline was computed by a FE model where the elements at the centerline were given liquid properties in order to account for the strain localization in this region.

Drezet et al. [7] used the RGD criterion [8] to study the susceptibility for solidification centerline cracking in laser-welded aluminum alloys. The RDG criterion states that hot cracking forms if the local pressure in the liquid falls below a given cavitation pressure [7].

Bordreuil et al. used cellular automata together with the RDG criterion to study weld solidification cracking in aluminum alloy 6061 [9]. Finite element analysis was used to compute the macroscopic temperature and strain fields in a 3-mm thick plate with autogenous GTAW. The plate had a constant tensile load during the welding, in the direction of the weld. The temperature field from the FE model was used to construct a two-dimensional microstructure in the fusion zone with cellular automata. The liquid pressure in the interconnecting grain boundary liquid films (GBLFs), given by the cellular automata model, was computed with the RDG criterion. The plastic strain rate from the FE model, normal to the GBLF and multiplied by a localization factor that is proportional to the ratio of the grain diameter to the GBLF thickness, was used in the RDG criterion.

One of the most recent models for simulation of weld hot cracking is developed by Rajani et al. [10]. A three-dimensional granular model is used to simulate the interconnecting intergranular liquid flow in a microstructure with both columnar and equiaxed grains. The granular grains are generated from Voronoi diagrams and the intergranular liquid flow is modeled as a Poiseuille flow between parallel plates. The liquid flow is coupled with the mechanical deformation obtained from a FE model. The susceptibility for cracking is determined by Kou’s crack criterion [11].

In this study, a new model is proposed for simulating the resistance to weld solidification cracking (WSC). The model is developed to evaluate the crack susceptibility in the entire fusion zone, and therefore is not limited to centerline cracking, as is the case with some of the previously mentioned models. The main feature with this crack model is its pore-based crack criterion where a crack is assumed to form from a growing pore. Crack initiation is predicted to occur when the GBLF pressure goes below a fracture pressure, which corresponds to the pressure that is required to stabilize a rotational symmetric pore of a certain size in a GBLF with a given thickness, i.e., the pressure required to balance the surface tension of the pore. The derivation and more details of this criterion can be found in part I of this work [12]. A major challenge with this crack criterion is its depends on the GBLF pressure and the GBLF thickness at the location where it is evaluated. These quantities are determined from the macroscopic mechanical strains and temperature fields of the weld by a model presented in part II of this study [13]. In this paper, the third in the series, we evaluate the crack criterion from part I on Varestraint tests of the nickel-based superalloy alloy 718. In order to do so, a FE model of the Varestarint test is developed. The main challenge with this FE model is its material model for the mechanical behavior of the solidifying material, which is described in detail in this paper. Results from the Varestraint tests show that computed crack susceptible region, crack orientations, and crack widths are in fairly good agreement with experimental results.

2 Material and experimental procedure

The material and the Varestraint tests that were used to calibrate and evaluate the pore-based crack model, developed in parts I and II of this study, are described in this chapter.

2.1 Alloy 718

The nickel-based superalloy alloy 718 was used for the Varestraint tests in this study. It is a precipitation-hardening nickel-iron-chromium alloy, containing significant amounts of niobium and molybdenum, along with lesser amounts of aluminum and titanium. The composition limits, given by the Special Metals Corporation [14], are shown in Table 1. The \(\sim \) 50 wt% nickel, \(\sim \) 20 wt% chromium, and \(\sim \) 20 wt% iron matrix are strengthened primarily by \(\sim \) 5 wt% niobium. Niobium forms the primary strengthening precipitate \(\gamma ^{\prime \prime }\)(Ni3Nb). In an age-hardened condition, alloy 718 contains approximately 20 volume percent \(\gamma ^{\prime \prime }\). Alloy 718 is the predominant nickel-iron-based superalloy, representing nearly half of the total quantity of superalloys used throughout the world. It is extensively used for high-temperature applications such as aerospace engines, gas turbines, and nuclear reactors. It maintains excellent corrosion and oxidation resistance up to 980 ∘C, and excellent resistance to creep and stress rupture up to 700 ∘C. Alloy 718 has outstanding weldability with high resistance to strain-age cracking, owing to the sluggish precipitation hardening response. However, it can have problems with liquation and solidification cracking.

2.2 The Varestraint test

The Varestraint test is an extrinsic (externally loaded) weldability test. It was developed in the 1960s by Savage and Lundin at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute [15]. This test allows the study of hot cracking susceptibility by a systematic procedure on small, simple test specimens [16]. The influence of material, welding process, and constraint factors on the hot cracking behavior can be studied. The idea is to rapidly apply an augmented strain during the welding of a plate. The amount of augmented tensile strain (due to bending), εaug, at the coupon surface depends on the material thickness and the radius of the die block according to the following equation:

where t is the sample thickness and R is the radius of the die block. This procedure provided a way to simulate the effect of large strains associated with highly restrained production welds [16]. The augmented strain is simply altered by changing the die block radius. The bending is applied along the length of the weld that is made on the sample.

The Varestraint test setup used in this study is shown in Fig. 1a. Figure 1 b shows the test plate before the start of the test and Fig. 1 c shows the test plate after the end of the test. The plate is bent over the die block by a vertical moment of the rollers while the die block is stationary. Support bars are used to reduce kinking of the test specimen.

a Varestraint test setup with press, welding robot, and hydraulic system; b test plate in the press before bending; c test plate in the press after bending. From [17]

2.3 Experimental procedure

Varestarint tests with 0.4%, 0.8%, and 1.1% augmented strains were performed. All test specimens were 3.2-mm thick plates that were annealed before the testing. The dimensions of the plates were 60 × 150 mm and the dimensions of the support plates were 10 × 20 × 300 mm. The starting position of the weld electrode was 40 mm from the contact point between the plate and the die block. The bending was initiated when the weld electrode had travel 40 mm (i.e., at the location of the contact point between the plate and the die). The welding continued for 5 s after the initiation of the bending. Autogenous bead-on-plate TIG welding was used. The welding current was constant 70 A, with automatic voltage regulation. With an estimated voltage of 10 V, the welding power can be computed from the welding current and the welding voltage to 700 W. The welding speed was 1 mm/s and the stroke rate was 10 mm/s (i.e., the vertical bending speed). Furthermore, the electrode type was a WT 20 (ThO2) with 2.4-mm diameter. The electrode tip angle was 50∘. Negative polarity in the torch was used and the arc length was 2 mm. The shield gas was pure argon at a flow rate of 15 slpm. The diameter of the gas cup was 13 mm.

After the Varestraint tests were finished, the locations, lengths, and widths of the cracks that could be found in these tests were measured with a Nikon Eclipse MA200 microscope. Only surface cracks were considered in this study. This is because the bending strains are largest at the weld surface and therefore we assume that this region is most crack susceptible. And because this work is focusing on solidification cracking, only cracks in the fusion zone were considered. Figure 2 shows the locations and the lengths of the surface cracks that were found in the tests. The measured mean crack widths for some of the cracks are also shown in the figure.

Measured crack locations, crack lengths, and mean crack widths on the weld surface for Varestraint tests with a 0.8% augmented strain, and b 1.1% augmented strain. The x-coordinate represents the distance from the weld start while the y-coordinate represents the distance from the weld centerline. The dashed lines correspond to the fusion lines

The figure shows results from tests with 0.8% and 1.1% augmented strains. No cracks could be found in the samples with 0.4% augmented strains. Even though no cracks could be found in the 0.4% tests in this study, the 0.4% augmented strain was considered to be the threshold strain for crack initiation. This is in agreement with Lingenfelter [18], who reported a small amount of cracking in Varestraint tests with 0.4% strain. Both Knock [19] and Quigley [20] reported a slightly higher threshold strain of 0.5% augmented strain for crack initiation.

3 Material model

In order to calibrate and evaluate the WSC model, which was developed in parts I and II of this study, on Varestraint tests of alloy 718, the temperature field and macroscopic strain fields of the Varestraint tests must be known. These fields are used to calculate the GBLF pressure (see part II [13]), which in turn is used to compute the crack initiation length (see part 1 [12]). In this study, the temperature and macroscopic mechanical strain fields were obtained from a finite element computational welding mechanics (CWM) model of the Varestraint test. Classical CWM models are normally used for computing deformations and residual stresses, which are not highly sensitive on the material properties at high temperatures. Therefore, often a cut-off temperature of about 70% of the homologous temperature, Tm, is used, above which the material properties are set to constant values [21]. Thus, the material models in classical CWM models cannot be used in the study of WSC because they cannot resolve the high-temperature mechanical behavior of the mushy zone where the WSCs are located. To accurately model the mechanical behavior of the mushy zone is very difficult. The solid in the mush is porous; thus, plastic deformations of the solid skeleton are not just dependent on the deviatoric stress state, as in J2 plasticity; it is also dependent on the hydrostatic pressure. This is especially true at lower fractions of solid. In order to capture behaviors like this, material models like Cam-Clay can be used [22]. A major drawback with these models is that they are very complicated to calibrate. Another problem with the mushy zone is that it is anisotropic when it contains columnar dendrites. To the knowledge of the authors, there has never been published any work on CWM models with material models that can handle these problems. However, Goldak et al. [23, 24] have presented a preliminary attempt to model stresses and strains close to the weld pool with isotropic J2 plasticity and different constitutive equations for different temperature intervals. A linear viscous model is used when the temperature is above 0.8 Tm. In the temperature range 0.5 Tm < T < 0.8 Tm, a rate-dependent plasticity model is used and for temperatures below 0.5 Tm, a rate-independent plasticity model is used. Inspired by Goldak’s model, we present in this chapter a material model for alloy 718 for estimating the mechanical and thermal behavior of the mushy zone.

3.1 Thermal properties

In this section, the thermal properties of the material model for alloy 718 are presented.

3.1.1 Solid fraction

The solid fraction is an important variable in the WSC model. It is used to calculate both the solidification velocity and to determined average material properties of the mushy zone. In this study, we use a temperature-dependent solid fraction determined by a multicomponent Scheil-Gulliver model (see part II). Sames et al. [25] have used the Scheil module and the nickel database TTNi7 in the software package Thermo-Calc to compute the solid mole fraction, as a function of temperature, for alloy 718. The result is shown in Fig. 3.

Solid mole fraction of alloy 718 as a function of temperature. Plotted from data obtained in [25]

From the plot, it can be seen that the predicted liquidus and solidus temperatures are approximately Tl = 1360 ∘C and Ts = 1100 ∘C, respectively.

3.1.2 Thermal conductivity

The thermal conductivity of alloy 718, both in the solid and liquid phase, has been estimated by electrical resistivity measurements using the Wiedemann-Franz-Lorenz relation. The results are reported in [26] for a wide range of temperatures. This measurement technique is not accurate in the mushy zone because of the coexistence of both liquid and solid in this region. To obtain the thermal conductivity of the mushy zone, the conductivities of the solid and liquid phases were extrapolated into the temperature range of the mush, i.e, Ts < T < Tl, and the conductivity of the mush was calculated by the following linear mixture rule:

where ks and kl are the extrapolated thermal conductivities of the solid and liquid phases, respectively. fs is the volume fraction of solid. To account for heat transfer by convection in the weld pool, the thermal conductivity of the liquid phase was increased by a factor of 5 (i.e, for T > Tl). This is the same factor as Feng et al. [27] used in their CWM model for a research Ni-based superalloy. The resulting thermal conductivity in the temperature range 0 < T < 1600 ∘C is shown in Fig. 4a.

3.1.3 Specific heat capacity

The specific heat capacity of alloy 718 has been measured by DSC. The results are reported in [26] for a wide range of temperatures, both in the solid and liquid phase. As for the thermal conductivity, the specific heat capacity in the mushy zone was determined by a linear mixture rule as follows:

where cp,s and cp,l are the extrapolated specific heat capacities of the solid and liquid phases, respectively. Figure 4 a shows the resulting specific heat capacity in the temperature range 0 < T < 1600 ∘C.

3.1.4 Latent heat of fusion

Antonsson et al. [28] have measured the latent heat of fusion, Lf, for alloy 718 with DTA, and obtained a value of 241 kJ/kg. The amount of released latent heat during the solidification, in a temperature range T2 < T < T1, can be written as follows:

Equation 4 was used to distribute the latent heat of fusion over the whole solidification interval Ts < T < Tl in the FE model in the next chapter.

3.2 Mechanical properties

3.2.1 Poisson’s ratio and Young’s modulus

The alloy 718 plates in this study were assumed to be isotropic. Thus, the elastic properties can be characterized by Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio. The latter has a smaller influence on plastic deformations and was set to a constant value of ν = 0.29 [14]. Young’s modulus of alloy 718 in solid phase has been measured by the Special Metals Corporation up to 1090 ∘C by an ultrasonic method. The measured values are reported in [14].

In order to simplify the mechanical behavior of the material that is in a liquid state, we consider it to be a “soft” isotropic solid with the same Poisson’s ratio as the fully solid phase (i.e., ν = 0.29). Young’s modulus of this “soft” material was determined from the bulk modulus of the liquid. The authors could not find any information about the bulk modulus for liquid alloy 718. Only for liquid iron could information of the bulk modulus be found, which is one of the main elements in alloy 718 (the others are nickel and chrome). It has been determined by Belashchenko et al. [29] who used molecular dynamics to calculate it to Kl = 62 GPa. Due to the lack of data, we assume that the bulk modulus of liquid alloy 718 is the same as the one for liquid iron. Young’s modulus for the isotropic “soft” material can then be obtained as follows:

A linear mixture rule was used to estimate Young’s modulus of the mushy zone. The mushy zone was assumed to have the same Young’s modulus at temperatures above the coherent temperature as the liquid phase. This is because the mush cannot transmit tensile loads above the coherent temperature. Young’s modulus can then be written as follows:

where Es is Young’s modulus of the solid phase, which is extrapolated into the mushy zone, and El is Young’s modulus of the liquid phase. Tc is the coherent temperature, whose value is 1278 ∘C in the fusion zone (see Section 3.2.3 for more information about Tc). Furthermore, in Section 3.2.3, a constitutive model for the “soft” solid is presented. Figure 4 b shows the resulting Young’s modulus in the temperature range 0 < T < 1600 ∘C.

3.2.2 Thermal expansion coefficient and solidification shrinkage factor

The volumetric expansion of alloy 718 has been measured by Blumm et al. [30] with an on-heating dilatometer test. This volumetric expansion can be transformed into a linear expansion by division with 3, which in turn can be differentiated with respect to the temperature to give the tangent thermal expansion coefficient. The material in the mushy zone is assumed to have the same thermal expansion as the solid skeleton of the mush, up to the coherent temperature. The solid skeleton in turn is assume to have the same thermal expansion as the full solid phase, which is determined by extrapolating the thermal expansion coefficient of the solid phase into the mushy zone. For higher temperatures than the coherent temperature, thermal expansion of the material is assumed to only cause liquid flows, and no straining of the solid skeleton of the mush. The thermal expansion coefficient was therefore set to zero for temperatures above the coherent temperature. Figure 4b shows the resulting thermal expansion coefficient in the temperature range 0 < T < 1600 ∘C.

Blumm et al. [30] also measured the volumetric increase due to melting of alloy 718 with the dilatometer test. It was estimated to 3.1%. This value was used for the solidification shrinkage factor β in the grain boundary liquid pressure model in part II of this study.

3.2.3 Plasticity model

We approximate alloy 718 as an isotropic elasto-plastic material that is governed by von Mises plasticity with isotropic hardening. The region that contains liquid is approximated as a “soft” isotropic elasto-plastic solid. Four different constitutive models, valid in different temperature intervals, are used to model the mechanical behavior. These are as follows:

20 ≤ T ≤ 700 ∘C

From room temperature up to 700 ∘C, and for effective plastic strains, \(\overline {\varepsilon }^{p}\), below 0.1, alloy 718 is almost rate-independent. Plastic strains above 0.1 are never achieved in the Varestraint tests in this study. Thus, the rate dependency can be neglected. The following simple regression model is used to estimate the yield stress, σy, in this temperature range, where it is a function of only effective plastic strain, \(\overline {\varepsilon }^{p}\), and temperature, T, as follows:

The model parameters were calibrated to tensile tests, performed at 20, 200, 600, and 700 ∘C. Their optimized values are given in Table 2.

700∘C < T ≤ 1050 ∘C

For temperatures above 700 ∘C, alloy 718 is strain rate-dependent. In the temperature range 700 ∘C < T ≤ 1050 ∘C, the viscoplastic model by Chen et al. [31] was used. This model was developed for hot forming of alloy 718 at temperatures up to 1100 ∘C. The yield stress of the model is given by the following:

where ψ and ξ are constants, and σp and εp are the peak stress and peak strain, respectively, given by the following:

and

where α, A, n, B1, and B2 are constants. Z is the Zener–Hollomon parameter, i.e.,

where Q is a constant, \(\overline {R}\) is the gas molar constant, and T is the temperature in Kelvin. All parameter values are given in Table 3.

The effective plastic strain, which act as state variable for hardening in the above model, was reset to zero for temperatures above 1100 ∘C, in order to account for the fast recovery that occurs at high temperatures. Thus, effective plastic strains that occur above this temperature do not contribute to the hardening of the material.

1050 ∘C < T ≤ Tc

In this temperature range, liquid and solid are coexisting, but because T ≤ Tc, the solid skeleton of the mush can still transmit loads. To simplify the mechanical behavior of the material in this region, we consider it to be a “soft” homogeneous isotropic solid, which is weakened by the presences of liquid. The following simple rate-dependent material model is used for this “soft” solid, which is based on in situ solidification experiments by Antonsson et al. [32]. They used a mirror furnace to heat tensile test specimens about 5 ∘C above the liquidus temperature. This resulted in a 5-mm long liquid zone that was stabilized by the surface tension of the liquid. After being heated to the liquid state, the test specimens were cooled to given holding temperatures, at a rate of 400 ∘C/min. When the given hold temperature was reached, tensile testing was performed at a rate of 0.1 s− 1 until failure occurred. The plot in Fig. 5 shows the measured ultimate tensile strength, UTS, of the in situ samples at different holding temperatures. The figure also shows the UTS for high-temperature solution heat-treated samples, HST, of alloy 718, measured by Antonsson et al. [32]. These samples were heated in the mirror furnace to a peak temperature of 1210 ∘C, approximately 10–20 ∘C below the zero-strength temperature, ZST. After the heating, the samples were cooled at a rate of 400 ∘C/min to a predetermined tensile test hold temperature. The UTS of the HST samples in the figure have been extended to the ZST by extrapolation [32].

For temperatures in the range 900 < T < 1050 ∘C, which is not shown in the figure, the in situ and HST materials have nearly the same UTS values, despite their dissimilar microstructures [32].

In this study, the UTS data for the in situ and HST material was used to estimate the yield stress of the material in the FZ and the PMZ, respectively, at temperatures above 1050 ∘C. The in situ solidified samples exhibited a dendritic microstructure. Even though the cooling rate was not as high as in welding, the resulting microstructure may be thought of as being a rough estimate of a microstructure found in the FZ of a weld, whereas the HST material can be thought of as a representation of the material in the PMZ, where grain boundary liquid films are formed, but not all of the original grains are completely melted.

To derive the yield stress from the UTS, the material in the FZ and the PMZ was assumed to be ideally plastic. This is a fairly good approximation for alloy 718 at temperatures between 1050 and 1200∘C, as hot compression tests have shown [31, 33,34,35,36]. These hot compression tests also show that alloy 718 has a high dependency on the strain rate at high temperatures. The UTS data from Antonsson’s experiments were obtained at a single strain rate of approximately 0.1 s− 1. This is a rather high strain rate for welding; the solidifying material experience only such a high strain rate during the bending phase of the Varestraint test. To compensate for the strain rate effect on the yield strength, the UTS was multiplied by the following factor:

where σy,1050 is the yield stress given by Chen’s flow stress model in Eq. 8, evaluated at T = 1050 ∘C and \(\overline {\varepsilon }^{p} = 0\), for a given value of \({\dot {\overline {\varepsilon }}}^{p}\). It should be noted that σy,1050 is a function of the effective plastic strain rate only, and represents the effect of the strain rate on the initial yield stress of alloy 718 at 1050 ∘C. The constant U in Eq. 12 corresponds to the value of σy,1050 at \({\dot {\overline {\varepsilon }}}^{p} = 0.1 ~ \mathrm {s}^{-1}\). A yield stress model is now derived as follows. Let pfz and ppmz be fitted curves to the UTS data for the in situ and HST samples, respectively, which are shown in Fig. 5. The previous assumption of ideal plasticity gives that the yield stress is the same as the UTS, and it can therefore be written as follows in the temperature range 1050 ∘C < T ≤ Tc:

where f is given by Eq. 12. Tpeak is the peak temperature, which indicates whether the material has been completely melted or not, and therefore belongs to the FZ or the PMZ. The coherent temperatures, Tc, for the FZ and the PMZ were determined from the zero rots of pfz and ppmz, respectively, which are Tc = 1278 ∘C for the FZ and Tc = 1230 ∘C for the PMZ.

3.2.4 T > Tc

For temperatures above Tc, the material was still approximated as a “soft” isotropic solid, but now with more liquid-like properties. The following flow stress model, where the yield stress is proportional to the strain rate in order to “resemble” the Newtonian behavior of the liquid [37], was used as follows:

where C is a calibration constant and \(\sigma _{y,{\min }}\) is the minimum allowed flow stress that prevents numerical difficulties, which was set to 0.01 MPa in this study. C was determined so that \(\sigma _{y} = 2\sigma _{y,{\min }}\) at \({\dot {\overline {\varepsilon }}}^{p} = 10^{-3}\) 1/s, which gives C = 10 MPas.

3.2.5 Changing constitutive equations in time and in space

In the above, four different constitutive equations, valid in different temperature ranges, are used to model the mechanical behavior of alloy 718. Thus, it is necessary to change constitutive equations in time and space when the temperature field changes. That causes no problems in a FE model [24]. The initial conditions required for each time step of a FE model are the initial geometry, initial stress, initial strain, the boundary conditions of the previous and current time steps, and the constitutive equations in the interior of the time step; there is no need to define the constitutive equation at times earlier than the previous time step [24].

3.3 Additional material data

In addition to the macroscopic temperature and strain fields, the pressure model in part II and the crack criterion in part I require the liquid viscosity and the gas-liquid interfacial energy in order to be evaluated. The following data were used for these quantities.

3.3.1 Liquid viscosity

Saunders et al. [38] have computed the dynamic viscosity of alloy 718 with the software package JMatPro for the entire solidification temperature rage. It can be expressed as a second-order polynomial in temperature as follows:

valid in the range 1100 < T < 1360 ∘C. This viscosity was used in the present study.

3.3.2 Gas-Liquid interface energy

To compute the crack initiation index (CII) in part I of this study, the factor \(\gamma _{gl}\cos \theta \) must be known, where γgl is the gas-liquid interface energy and 𝜃 is the contact angle (see part I). We assume that the solid phase is well wetted by the liquid phase, which makes 𝜃 small. Thus, \(\cos \theta \) can be approximated as 1.

Brooks et al. [26] have measured the surface tension of alloy 718 by the oscillating drop method. They found that it varies linearly with temperature as follows:

in the temperature range 1350 < T < 1600 ∘C. We assume that γgl can be approximated by this surface tension, and assume that Eq. (16) is valid to be extrapolated down to the solidus temperature.

4 The FE model of the Varestraint test

The Varestraint test was implemented in the software package MSC Marc as a thermo-mechanical finite element model. The various parts of this FE model are described below.

4.1 Heat source

The weld heat input is modeled with a double ellipsoid heat source, which is represented by the ellipsoid axes a, b, c1, and c2 [21] (see Fig. 6). No heat flux is applied outside the volume of the double ellipsoid, which is spanned by these axes. The efficiency of the heat source is adjusted by the η parameter. The ellipsoid axes a, b, c1, c2, and the η parameter, together with the emissivity and film coefficient (see below), were obtained by inverse modeling of an autogenous weld on a 3.2-mm thick plate of alloy 718. The plate had four thermocouples at its upper surface, located at 0.9, 1.0, 1.1, and 2.3 mm from the fusion line of the weld. The parameters were calibrated such that the computed temperature history at the locations of the thermocouples, obtained from the FE model, agreed with the temperature history obtained from the thermocouples. These parameters were also calibrated so that the location of the computed fusion boundary in the cross-section of the weld agreed with the one from experiments, which was obtained by cutting the test sample and etched it. The calibrated values are as follows: a = 3.0 mm, b = 1.2 mm, c1 = 1.5 mm, c2 = 3.0 mm, η = 3.0.

4.2 Thermal boundary conditions

The heat flux on the free surfaces was modeled with the boundary condition as follows:

where hconv is the film coefficient, 𝜖 is the emissivity factor, σ is Stefan Boltzmann’s constant, T and TRT are the surface and the room temperatures, respectively. hf and 𝜖 were determined from the above inverse modeling, which gave hconv = 12 W/m2 K and 𝜖 = 0.3.

The Varestraint test has thermal contacts between the test specimen and the die block, and between the test specimen and the support plates. The heat flux at these contacts was obtained from the following:

where T2 − T1 is the temperature difference across the contact and hcond is the heat transfer coefficient. hcond is assumed to vary linearly with the contact pressure, pcont, (i.e., the mechanical pressure at the contact point) as given by Karbasian et al. [39]:

where C3 is a calibration constant added by the authors. By adjusting this constant, the location of the solidus isotherm can be adjusted, and hence the location of the computed crack susceptible region. Its value was calibrated such that the locations of the cracks found in the experimental Varestraint tests with 0.8 % augmented strain agreed with the location of the computed crack susceptible region for the test with the same augmented strain. A value of 1.28 was used for C3, which is discussed in more detail in Section 6.2 below.

4.3 Implementation of material models

The material models in Section 3.2.3 were implemented into MSC Marc via the user subroutine WKSLP.

4.4 Varestraint setup

The Varestraint test is symmetric along the weld centerline; therefore, only one half of the test was needed to be modeled when a symmetric boundary condition is used (see Fig. 7a). Approximately 352,000, eight-nodded, fully integrated elements were used. The rollers that press on the support plate were modeled as rigid bodies. Local remeshing was used to refine all elements in the mushy zone (see Fig. 7b). The refined element size was 125 μm.

The bending of the test specimen was performed by a displacement boundary condition that controlled the movements of the rollers. The full bend times were 1.5, 3.0, and 3.6 s for the 0.4%, 0.8%, and 1.1% tests, respectively. All contacts had the segment-to-segment option. During the first 25 s, a fixed time step of 0.2 s was used. For the remaining time, a fixed time step of 0.05 s was used. The analysis was implicit. Relative convergence criteria, both residual force and displacement, were used with a tolerance of 1%. For the thermal field, a convergence tolerance of 0.1 ∘C was used. The updated Lagrange formulation with large strains was used. The lumped capacity matrix option was used to avoid oscillations in the temperature field, as well as the constant temperature option, which ensures uniform thermal strains within an element. The “Adjust to Input” power option in MSC Marc was used to ensure a constant input of the weld heat flux. The Pardiso Direct Sparse matrix solver was used with 16-cores multi-threading. The total wall time of the simulation was about 12 h.

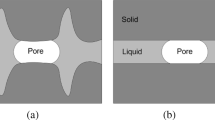

5 Procedure for determining crack initiation length

We estimate the crack susceptibility for WSC by a crack initiation length, CIL (see part I). This CIL corresponds to the length of a grain boundary, GB, where a crack initiation index, CII, has been larger than zero at the location of the terminal solidification. Note that the terminal solidification occurs at the intersection of the GBLF and solidus isotherm. It will therefore move with time because of the movement of the solidus isotherm. The CII is defined as the difference between a fracture pressure and the GBLF pressure, normalized by the atmospheric pressure. The fracture pressure is defined in part I as the pressure that is required to balance the surface tension of a rotational symmetric pore with a 50-μm radius. This pore size was considered as a pore that forms a severe defect. The fracture pressure depends on the GBLF thickness and the gas concentration in the GBLF, which is discussed in detail in part I. From the definitions of the CII and the fracture pressure, it is realized that if the CII is less than zero, the GBLF pressure must be larger than the fracture pressure, and therefore the GBLF pressure cannot stabilize a 500-μm pore, and we assume that there is no risk of cracking (see part I for more information).

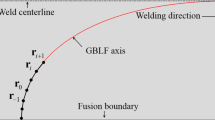

In order to compute the CIL, the GBLF pressure and the GBLF thickness must be known. These quantities are determined as follows. A GBLF axis is defined as the same axis as the axis of columnar grain that always growths perpendicular to the liquidus isotherm with zero undercooling to solidification (see part II). This axis can be computed from the temperature field of the FE model in chapter 4 by giving a point that the axis should traverse and then integrate Eq. 3 in part II with a Python script. Figure 8 a and b shows computed GBLF axes at the weld surface of a Varestraint test with 1.1% augmented strain. The axes are separated approximately 1 mm from each other at the fusion line, and together they cover the whole crack susceptible region of the test. Figure 8 a also shows the computed CIL associated with each GBLF, which will be discussed in the next chapter. The x- and y-coordinates in Fig. 8 b represent the distances from the weld start and the weld centerline, respectively.

For the part of a GBLF axis that is located between the solidus and liquidus isotherms, we consider a one-dimensional GBLF flow that always occurs in the direction of the GBLF axis (see part II). This flow is induced by deformations of the GBLF and by solidification shrinkage. We define the normal of the GBLF to be in the same direction as the largest mechanical strain rate perpendicular to the GBLF axis, \(\dot {\varepsilon }_{\perp ,{\max \nolimits }}^{m}\) (see part II). By doing so, the film normal will always be oriented such that the maximum deformation always occurs perpendicular to it. \(\dot {\varepsilon }_{\perp ,{\max \nolimits }}^{m}\) is determined from the FE model in chapter 4. It is computed from the mechanical strain fields, evaluated in sample points on the GBLF axis. The spacings between the sample points are approximately the same as the element size. The sample points move with the mesh as material points, and they contain data that are obtained by interpolating data from the nodes that belong to the same element that the sample point is located in. The sample points are constructed by the previous Python script that is used to trace out the GBLF axis. For every sample point, temperature, strains, and displacement data are stored for every time step. These data are stored in a text file that can be imported into Matlab for computing the GBLF pressure. Figure 8 b shows the sample points on the leftmost GBLF axis, which are shown as black crosses.

In order to compute the GBLF pressure, the rate of change of the GBLF thickness, \(2\dot {h}\), must be known. In this work, we obtain this from the following:

where h is the half GBLF thickness and v∗ is the solidification velocity of the solid-liquid interface of the GBLF (see part II). l0 is a length scale that represents the amount of surrounding solid phase of the GBLF that can transmit normal tensile loads. This value is temperature-dependent and we assume that it is zero at Tl, the same length as the primary dendrite arm spacing at Tc, and the same length as the diameter of a grain cluster at Ts. In between these temperatures, l0 is assume to vary linearly. See part II for a detailed discussion on l0. The diameter of a grain cluster is not know. For simplicity, it was assumed to be divisible by the primary dendrite arm distance, λ1, such that l0 at Ts can be written as follows:

where C2 is a calibration constant, which is determined by inverse modeling as discussed in the next chapter. Furthermore, λ1 is determined from the following simple relation as follows:

where GL is the magnitude of the temperature gradient and ∂T/∂t is the cooling rate, both evaluated at the intersection of the GBLF axis and the liquidus isotherm. C1 is a calibration constant that is determined by adjustments to measurements from a micrograph, which is discussed in the next chapter. The solidification velocity in Eq. 20 is determined as follows:

where ∂T/∂t is the cooling rate, which is determined from the temperature data of the sample points on the GBLF axis. The fraction of solid is determined from the temperature data and the Scheil curve in Fig. 3 (see part II for more details).

Once v∗, h, and the flow direction (which is given by the direction of GBLF axis) are known a mass balance can be performed for a small volume element that extends across the thickness of the GBLF. This mass balance leads to a first-order time invariant ODE where the mean liquid velocity across the film, \(\bar v\), is the dependent variable while the coordinate, s, along the GBLF axis is the independent variable. \(\bar v\) can be substituted by a pressure gradient as follows. For the part of the GBLF that goes through regions with more than 0.1 fractions of liquid, we assume a strong interaction between the GBLF flow and the secondary dendrite arms. This flow is considered to be a porous flow that can be approximated by Darcy’s law. Darcy’s law states that \(\bar v\) is proportional to the pressure gradient with a proportionality factor that depends on the permeability of the porous medium (see part II). For the rest of the GBLF that goes through regions with less than 0.1 fractions of liquid, we assume that the flow interaction with the secondary dendrite arms is not so strong. In this case, the flow is assumed to be better approximated by a Poiseuille parallel plate flow, which gives that \(\bar v\) is proportional to the pressure gradient with a proportionality factor that depends on the GBLF thickness.

By substituting the expressions for the pressure gradients instead of \(\bar v\) into the mass balance equation, it transforms to a second-order ODE where now the dependent variable is the GBLF pressure. This ODE can further be transformed into a first-order separable ODE, which can be integrated numerically along the GBLF axis between the intersection points that the axis makes with the solidus isotherm and the liquidus isotherm for a given time. In order to do so, four different boundary conditions on the pressure are required. At the liquidus intersection, we assume that the pressure is the same as the atmospheric pressure. At the solidus intersection, we set a condition on the pressure gradient, which accounts for the solidification shrinkage flow at the end of the film (see part II). At the junction between the Darcy and Poiseuille flows, we enforce the pressure and \(\bar v\) (which can be expressed as a pressure gradient) to be continuous (see part II). The integrand in the numerical integration is evaluated with sample point data for the corresponding time. Note that there is no flow interaction between different GBLFs.

Finally, when the GBLF pressure and the GBLF thickness are known, the CIL can be computed as the total length of the GBLF axis where the CII has been larger than zero, at the location of the terminal solidification, as was stated previously. The CII is determined from the GBLF pressure and the fracture pressure, evaluated on the GBLF axis, via Eq. (37) in part I. The fracture pressure, in turn, is determined from Fig. 10 in part I by the computed GBLF thickness (at the location of the evaluation on the GBLF axis) and by a given fixed gas concentration. Because there is no flow interactions between different GBLFs, the CIL for a given GBLF can be determined without knowledge about other GBLFs.

6 Results and discussion

The WSC model was calibrated and evaluated on the Varestraint tests in chapter 2, implemented into the FE model in chapter 4. Because the bending strain in a Varestraint test is largest at the surface, the weld surface was assumed to be the most crack susceptible region of the test. Therefore, only the crack susceptibility at the weld surface was studied in this work, and all GBLF axes were constructed at the weld surface. However, in agreement with resent in situ experiment (see part I), we assume that the cracking occurs beneath the surface. And, even though the GBLF pressure is computed from the macroscopic temperature and mechanical strain fields at the surface of the weld (i.e., on the GBLF axes located on the surface), we consider the resulting GBLF flow to occur at a small distance under the surface, a distance large enough such that flow interactions with the surface can be neglected, and the GBLF pressure can be computed with the model in part II. Thus, e.g., the effect of the surface capillary on the flow is neglected. The crack susceptible region was covered with GBLF axes, separated approximately 1 mm from each other at the fusion line, in order to estimate the CIL over the whole crack susceptible region.

We assume that the hydrogen concentration in the weld pool is the same as what can be expected in a casting, i.e, about 2 ppm (see part I). Moreover, at the location of the terminal solidification, were cracking normally occur, we assume that this value has increased to 3.4 ppm due to segregation. It was computed from an equilibrium partition ratio of 0.589 (see part I). This value of the gas concentration was used when the fracture pressure is interpolated from Figure 10 in part I.

6.1 Calibration

Except for the parameters of the material model in chapter 3, the WSC model has three calibration parameters: C1 (Eq. 22), C2 (Eq. 21), and C3 (Eq. 19). These parameters were determined simultaneously by inverse modeling of Varestraint tests as follows. The C2 parameter, which is associated with the grain cluster size, was calibrated to the Varestraint test with 0.4% augmented strain. As discussed in Section 2.3, an augmented strain of 0.4% is assumed to be the threshold value for crack initiation. We represent the threshold value for crack initiation with a low value of the maximum CIL; in this study, it was set to 300 μm. The C2 parameter was calibrated such that the computed maximum CIL for the 0.4% strain test is 300 μm, which resulted in C2 = 40. With λ1 = 20 μm, this value corresponds to a grain cluster size of 0.8 mm (see Eq. 21). Figure 9 shows the computed CIL for the 0.4% test.

The C1 parameter, which is associated with λ1, was also calibrated to the 0.4% strain test. One of the experimental tests with 0.4% strain was cut transverse to the weld direction, approximately 30 mm from the weld start. The cut surface was then polished and etched, and λ1 was measured with a scanning electron microscope at a location 1 mm from the fusion boundary, and 0.1 mm below the weld surface. It was roughly measured to 20 μm. By inserting this value into Eq. 22, together with the values for GL and ∂T/∂t, evaluated at the location of the measurement by the FE model, a C1 value of 1.00 × 10− 3 was obtained.

Figure 10 shows the computed λ1 values at the weld surface with C1 = 1.00 × 10− 3 for the 0.4% test just before the bending starts. The largest values for λ1 are found at the fusion line due to the low solidification velocity in that region. The minimum values are found at a short distance from the fusion boundary, after which it increases monotonically up to the location of the weld centerline. Observe that the computed λ1 values are lower at the vicinity of the die block due to the higher cooling rates in this region because of the heat extraction to the die block.

The last calibration parameter, C3, was calibrated as follows. By altering the value of C3, the amount of heat transfer between the test specimen and the die block can be adjusted. This will shift the location of the solidus isotherm, and therefore also the location of the crack susceptible region. The C3 parameter was calibrated so that the region of the computed CIL for the Varestraint test with 0.8% augmented strain was centered with the region where the surfaces cracks, found from four experimental tests with 0.8% strain, are located. These two regions are approximately centered when C3 = 1.28. The computed CIL region, together with the surface cracks from four tests with 0.4% strain, are shown in Fig. 12.

A C3 value of 1.28 corresponds to a 28% larger heat transfer coefficient, hcond than predicted by the model in Karbasian et al. [39] (i.e., Eq. 19 with C3 = 1). There are a number of possible reasons for this. For example, the hcond model in [39] is an imperial model for hot sheet forming and it is not known how well it works for alloy 718 at high temperatures. Also, for the welds in the experimental tests, there was a small bulge on the underside the weld. This small bulge could not be captured by the FE model. Thus, due to the bulge, the contact pressure at the weld underside may have been larger in the experiments than in the FE model. And therefore was more heat conducted between the test specimen and the die block for the experiments than for the FE model. This can explain why we had to increase hcond in the FE model by 28%.

6.2 Evaluation

6.2.1 Temperature and fraction of liquid distribution

The temperature and the liquid fraction distributions at the weld surface for the Varestraint test with 0.4% augmented strain are shown in Fig. 11a, b, at the moment when the bending just starts. Only one half of the symmetric weld is shown in the plots. The x- and y-coordinates in the plots represent the distances from the weld start and the weld centerline, respectively. The welding direction is from the left to the right. For the time shown in the figures, the weld electrode has traveled 40 mm and are located just above the apex of the die block (i.e., just above the location of the contact between the test specimen and the die block). Only GBLFs with a solidus temperature inside the FZ are considered, i.e., GBLFs that extend out into the PMZ are not considered.

From Fig. 11a, it can be seen that the length of a GBLF that are in the temperature interval Ts < T < Tl is approximately 5 mm long. About 50% of this length is in a region with less than 0.2 fractions of liquid, as can be seen in Fig. 11b. Thus, a considerable part of a GBLF is in a vulnerable region where liquid flow may be difficult, which can increase the crack susceptibility.

6.2.2 Crack initiation length

CILs for Varestraint tests with 0.8% and 1.1% augmented strains have been computed by the WSC model. Figure 12 shows CILs for the 0.8% test together with experimental crack locations from four test specimens with the same strain. The computed CIL for the shown GBLF axes covers all cracks found in the experiments. Most of the cracks are located 0.5–2 mm from the weld centerline. This is also the region that has the GBLFs with the largest CILs. It is also interesting to note that the crack orientations roughly agree with the GBLF axes. This is an indication that the grain growth has been roughly perpendicular to the liquidus isotherm, which is the assumption that the grain growth model in this work is based on.

CILs for the 1.1% strain test together with the experimental crack locations found in two test specimens with the same strain are shown in Fig. 13 (and in Fig. 8a). The CILs for the shown GBLF axes almost covers all cracks found in the experiments. As for the 0.8% test, the majority of the cracks are located 0.5 to 2 mm from the weld centerline, and this is also the region where the model predicts the largest CILs. The agreement between the crack orientations and the GBLF axes is also fairly good for this test.

6.2.3 Estimated crack width

It is also interesting to compare experimental crack widths with the computed GBLF thickness at the location of the terminal solidification, which will be the estimated thickness of a pore when it is being frozen into the solid phase. Figure 14 shows the computed and the measured crack widths for the 0.8% test. The computed crack widths are largest 0.5 to 2 mm from the weld centerline. The agreement between the computed and measured crack widths is fairly good.

The computed and measured crack widths are also in fairly good agreement for the 1.1% test. This is shown in Fig. 15. The agreement between computed and measured crack widths is an indication that the strain localization model in this study (see part II) works fairly well.

6.3 Parameter sensitivity analysis

To study the influence of different model parameters on the CIL, a one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) parameter sensitivity analysis was performed. Each parameter value in the study were increased by 10% from a reference value, one at a time, while the rest of the parameters were fixed. The relative change in the CIL, CILrel,i, when the value of parameter i is increased by 10% (the other parameters being fixed) is defined as follows:

where CILp,i and CILref are the CIL with 10% increase in parameter i and the CIL with reference values for all parameters, respectively. The analysis was performed for the GBLF axis with the highest CIL value, which is the axis that intersects the fusion line approximately 31 mm from the weld start. Except for the calibration parameters C1 and C2, the sensitivity of \(\gamma _{\text {gl}} \cos \theta \), the solidification shrinkage (β), the strain localization length at the coherent temperature (\(l_{0,T_{c}}\)), the liquid fraction at the transition point between Poiseuille and Darcy flow (fl,trans), and the minimum half GBLF thickness (\(h_{{\min }}\)) were studied. To study the influence of the permeability and the viscosity on the CIL, the equation for the permeability (Eq. (36) in part II) and the equation for viscosity (Eq. 15) were multiplied by the coefficients Kcoeff and μcoeff, respectively, and the sensitivity in changes of these coefficients were studied. Table 4 shows the sensitivity analysis for Varestraint tests with 0.4, 0.8, and 1.1% augmented strains.

From the table, it can be seen that one of the most influential factors on the CIL is the permeability. This can be seen on the effect of Kcoeff, and even more on the effect of C1. Note that C1 is proportional to λ1, which in turn the permeability is proportional to in square (see Eq. (36) in part II). The C2 and \(\gamma _{\text {gl}} \cos \theta \) parameters are also very influential on the CIL. This reflects the importance of strain localization and surface tension. The sensitivity analysis also shows that viscosity is an important factor. Considerably less important is the solidification shrinkage factor, which only shows a weak influence on the CIL. This is because the liquid flow is significantly more dominated by the mechanical strain localization than the solidification shrinkage in the Varestraint test. Elements such as sulfur, phosphor, and boron are known to increase hot crack sensitivity. One reason for this is that these elements decrease the surface tension. A decrease in surface tension can lead to a large change in the CIL, as the above sensitivity analysis shows.

6.4 Limitations

6.4.1 Validation

The WSC model has been evaluated on Varestraint tests of alloy 718 with 0.8% and 1.1% augmented strains, and with constant welding speed and heat input. For these tests, the WSC model can quantify the cracking behavior fairly well. However, the conditions in a Varestraint test is quite different from the ones in a real weld, but we hope that the WSC model can be calibrated with a Varestraint test and that it then can be used for real weld situations where process parameters (e.g., welding speed and heat input), types of welding joints, and sheet thickness may vary. If the WSC model can handle this is still unknown, testing needs to be done in order to verify this.

The Varestraint test may not be the optimum weldability test for calibrating the crack model on sheet metals. The conditions in a Varestraint test may be rather different from the conditions in a real weld on a sheet metal. For example, the applied strain varies throughout the coupon thickness. Also, hinging is difficult to completely avoid when testing sheet metal with the Varestraint test. When welding sheet metals, the weld is normally fully penetrating. For the Varestraint test, the weld cannot be penetrating because that would destroy the die block. However, even though the weld is not penetrating, it can be difficult to not have a bulge on the underside of the weld. The test specimen can then ride on the bulge, which will alter the augmented strain and the heat transfer between the test specimen and the die block. The heat transfer between the test specimen and the die block is also difficult to model, and it requires a contact analysis, which makes the FE analysis much more computational heavy.

A better weldability test for calibrating and testing the WSC model on sheet metals is the controlled tensile weldability (CTW) test, developed at BAM Fedral Institute for Materials Research and Testing [3]. In this test, the test specimen is again a plate, but is now loaded in pure tension. The load can be applied prior to or during the welding, at a well controlled loading rate. The CTW test overcomes many of the problems associated with the Varestraint test. The loading is uniform throughout the thickness of the test plate, and fully penetrating welds can be used. The test is also more easy to model because there are no thermal or mechanical contacts between the test specimen and the support plates, and between the test specimen and the die block, as in the Varestraint test. The deformation of the test plate can simply be applied by a controlled displacement at one boundary of the plate.

A test similar to the CTW test is planned to be built so that the WSC model can be further tested. It can then be tested at conditions that resemble the conditions in real welds better than what is possible with the Varestraint test. With further testing, the ability of the WSC model to handle variations in welding speed and heat input could also be investigated.

6.4.2 One-dimensional flow

One of the major assumptions in the WSC model is that the direction of the GBLF flow always is in the growth direction and that there is no flow interaction between different GBLFs. This makes the WSC model computational cheap compared to, e.g., granular models. It just takes about one minute to compute the CIL for 10 GBLFs (not included the wall time of the FE model for obtaining the temperature and strain data). The approximation of 1D flow is assumed to be roughly valid when sheet metals of alloys with large solidification temperature intervals, and with fully penetrating welds are welded. In this case, long isolated GBLFs are assumed to exist due to the large solidification interval. And due to the fully penetrated welds, deformation and temperature variations in the thickness directions of the sheet metal are assumed to be small. Further, if we assume a state of plane stress in the sheet metal, GBLFs whose normals are perpendicular to the surface normal of the sheet will be mostly deformed. Because deformation and temperature do not vary much in the thickness direction of the sheet, the liquid flow in the thickness direction of these GBLFs are assumed to be small. Moreover, if we assume that the cracking occurs at a location close to the terminal solidification, then it can be assumed to occur in the part of the GBLF that is isolated from other GBLFs. Thus with the above conditions, the assumption of 1D flow is assumed to be roughly valid. However, if these conditions are not valid, this assumption becomes less valid, and more advanced models like granular models are required.

6.4.3 HAZ liquation cracking

HAZ liquation cracking could be found in the Varestraint tests in this study. But the WSC model cannot jet handle this type of cracking, and they were therefore ignored in this work. However, right now the WSC model is being extended to also cope with HAZ liquation cracking, and the result is planed to be published in the near future.

7 Conclusions

A computational welding mechanics model (CWM model) for Varestraint tests of alloy 718 has been developed. It has been used to calibrate and evaluate the weld solidification cracking model (WSC model) that was developed in parts I and II of this study. This WSC model computes a crack initiation length (CIL), which represents the length of a grain boundary where cracking may initiate, using data from the macroscopic temperature and the mechanical strain fields of the CWM model. Special emphasis was put on the material model of the CWM model in order to compute these fields in the high-temperature region where the cracking occurs.

The developed WSC model could estimate several WSC features of the Varestraint tests. For example, the location of the crack susceptible region, crack orientations, and crack widths, predicted by the WSC model, all agreed fairly well with experimental tests. A sensitivity analysis of the WSC model demonstrated that the permeability, the strain localization, and the surface tension are the parameters that influence the CIL most in the Varestraint tests, whereas solidification shrinkage had limited effect on the CIL.

References

Lippold JC (2014) Welding metallurgy and weldability, Wiley, New York

Lippold JC, Kiser SD, DuPont JN (2011) Welding metallurgy and weldability of nickel-base alloys. Wiley, New York

Kannengiesser T, Boellinghaus T (2014) Hot cracking tests—an overview of present technologies and applications. Welding in the World 58(3):397–421

Kou S (2003) Welding metallurgy. Wiley, New York

Feng Z (1994) A computational analysis of thermal and mechanical conditions for weld metal solidification cracking. WELDING IN THE WORLD-LONDON- 33:340–340

Ploshikhin V, Prikhodovsky A, Makhutin M, Ilin A, Zoch H-W (2005) Integrated mechanical-metallurgical approach to modeling of solidification cracking in welds. In: Hot cracking phenomena in welds. Springer, pp 223–244

Drezet J-M, Allehaux D (2008) Application of the rappaz-drezet-gremaud hot tearing criterion to welding of aluminium alloys. In: Hot cracking phenomena in welds II. Springer, pp 27–45

Rappaz M, Drezet J-M, Gremaud M (1999) A new hot-tearing criterion. Metallurgical and materials transactions A 30(2):449–455

Bordreuil C, Niel A (2014) Modelling of hot cracking in welding with a cellular automaton combined with an intergranular fluid flow model. Comput Mater Sci 82:442–450

Rajani HZ, Phillion A (2018) 3D multi-scale multi-physics modelling of hot cracking in welding. Mater Des 144:45–54

Kou S (2015) A criterion for cracking during solidification. Acta Mater 88:366–374

Draxler J, et al. (2019) Modeling and simulation of weld solidification cracking part I. Welding in the World: 1–14

Draxler J, et al. (2019) Modeling and simulation of weld solidification cracking part II. Welding in the World: 1–17

Metals S, et al. (2007) Inconel alloy 718, Publication Number SMC-045 Special Metals Corporation

Savage W, Lundin C (1965) The Varestraint test. Weld J 44:433–442

Andersson J (2011) Weldability of precipitation hardening superalloys–influence of microstructure. Chalmers University of Technology

Singh S (2018) Varestraint weldability testing of cast superalloys

Lingenfelter A (1989) Welding of inconel alloy 718: A historical overview. Superalloy 718:673–683

Knock NO (2010) Characterization of Inconel 718: using the Gleeble and Varestraint testing methods to determine the weldability of Inconel 718

Quigley S (2011) A quantitative study of the weldability of Inconel 718 using Gleeble and Varestraint test methods

Lindgren L-E (2014) Computational welding mechanics. Elsevier

Dantzig JA, Rappaz M (2016) Solidification: -Revised & Expanded EPFL press

Goldak J, Breiguine V, Hughes N, Zhou J, Dai N (1997) Thermal stress analysis in solids near the liquid region in welds, Mathematical Modelling of Weld Phenomena 3. Institute of Materials, 1 Carlton House Terrace, London, SW 1 Y 5 DB, UK, 1997., pp 543–570

Goldak JA, Akhlaghi M (2006) Computational welding mechanics. Springer Science & Business Media

Sames WJ, Unocic KA, Dehoff RR, Lolla T, Babu S S (2014) Thermal effects on microstructural heterogeneity of Inconel 718 materials fabricated by electron beam melting. J Mater Res 29(17):1920–1930

Mills KC (2002) Recommended values of thermophysical properties for selected commercial alloys. Woodhead Publishing

Feng Z, Zacharia T, David S (1997) Thermal stress development in a nickel based superalloy during weldability test. Welding journal, 76(11)

Antonsson T, Fredriksson H (2005) The effect of cooling rate on the solidification of Inconel 718. Metall Mater Trans B 36(1):85–96

Belashchenko DK, Mirzoev A, Ostrovski O (2011) Molecular dynamics modelling of liquid Fe-C alloys. High Temp Mater Processes 30(4-5):297–303

Blumm J, Henderson JB (2000) Measurement of the volumetric expansion and bulk density of metals in the solid and molten regions. High Temp High Pressures 32(1):109–114

Chen F, Liu J, Ou H, Lu B, Cui Z, Long H (2015) Flow characteristics and intrinsic workability of IN718 superalloy. Mater Sci Eng A 642:279–287

Azadian S (2004) Aspects of precipitation in alloy Inconel 718, Ph.D. dissertation, Luleå tekniska universitet

Wang Y, Shao W, Zhen L, Yang L, Zhang X (2008) Flow behavior and microstructures of superalloy 718 during high temperature deformation. Mater Sci Eng A 497(1-2):479–486

Nowotnik A, Pedrak P, Sieniawski J, Goral M (2012) Mechanical properties of hot deformed Inconel 718 and x750. J Achiev Mater Manuf Eng 50(2):74–80

Cai D, Xiong L, Liu W, Sun G, Yao M (2009) Characterization of hot deformation behavior of a Ni-base superalloy using processing map. Mater Des 30(3):921–925

Thomas A, El-Wahabi M, Cabrera J, Prado J (2006) High temperature deformation of Inconel 718. J Mater Process Technol 177(1-3):469–472

Li C, Thomas BG (2004) Thermomechanical finite-element model of shell behavior in continuous casting of steel. Metallurgical and MAterials transactions B 35(6):1151–1172

Saunders N, Guo Z, Li X, Miodownik A, Schille J-P (2004) Modelling the material properties and behaviour of Ni-based superalloys. Superalloys 2004:849–858

Karbasian H, Tekkaya AE (2010) A review on hot stamping. J Mater Process Technol 210(15):2103–2118

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Rosa Maria Pineda Huitron from the Material Science Department at Luleå Technical University for the help with evaluating the experimental Varestraint tests.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lulea University of Technology. This study is financially supported by the NFFP program, run by Swedish Armed Forces, Swedish Defence Material Administration, Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems, and GKN Aerospace (project no. 2013-01140 and 2017-04837).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Draxler, J., Edberg, J., Andersson, J. et al. Modeling and simulation of weld solidification cracking part III. Weld World 63, 1883–1901 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40194-019-00784-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40194-019-00784-3