Abstract

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is defined by abdominal pain and alterations in stool patterns. It is a common disease with a heavy burden on patients and providers. Pharmaceutical and psychiatric therapies have low success rates. A diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) has been suggested to treat symptoms of IBS by reducing consumption of poorly absorbed and indigestible carbohydrates. This decreases the amount of water in the bowel lumen and the amount of fermentable sugar available for colonic bacteria. Several recent randomized trials in patients treated for IBS with low-FODMAP diets have demonstrated improvements in IBS symptoms and stool characteristics. However, studies to date have had limitations, and the long-term efficacy and health impact of low-FODMAP diets is not known. Ongoing research will help address the benefits of low-FODMAP diets for IBS and other diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Drossman DA, Corazziari,E, Delvaux,M, Spiller,RC, Talley,NJ, Thompson,WG, Whitehead,WE (Eds): Rome III: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Third Edition. Degnon Associates, Inc. 2006.

Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:712–721. e4.

Hungin A, Whorwell P, Tack J, Mearin F. The prevalence, patterns and impact of irritable bowel syndrome: an international survey of 40,000 subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:643–50.

Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, et al. Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies, including hypnotherapy, in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014. doi:10.1038/ajg.2014.148.

Chey WY, Jin HO, Lee MH, Sun SW, Lee KY. Colonic motility abnormality in patients with irritable bowel syndrome exhibiting abdominal pain and diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1499–506.

Dinan TG, Quigley EM, Ahmed SM, Scully P, O’Brien S, O’Mahony L, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-gut axis dysregulation in irritable bowel syndrome: plasma cytokines as a potential biomarker? Gastroenterology. 2006;130:304–11.

Carroll IM, Ringel-Kulka T, Siddle JP, Ringel Y. Alterations in composition and diversity of the intestinal microbiota in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:521–e248.

Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, Zakko S, Ringel Y, Yu J, et al. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Eng J Med. 2011;364:22–32.

Codling C, O’Mahony L, Shanahan F, Quigley EM, Marchesi JR. A molecular analysis of fecal and mucosal bacterial communities in irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:392–7.

Al–Chaer ED, Kawasaki M, Pasricha PJ. A new model of chronic visceral hypersensitivity in adult rats induced by colon irritation during postnatal development. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1276–85.

Wilder-Smith CH, Robert-Yap J. Abnormal endogenous pain modulation and somatic and visceral hypersensitivity in female patients with irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3699–704.

Mertz H, Naliboff B, Munakata J, Niazi N, Mayer EA. Altered rectal perception is a biological marker of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:40–52.

Hayes PA, Fraher MH, Quigley EM. Irritable bowel syndrome: the role of food in pathogenesis and management. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;10:164.

Park M, Camilleri M. Is there a role of food allergy in irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia? A systematic review. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:595–607.

Barrett J, Gearry R, Muir J, Irving P, Rose R, Rosella O, et al. Dietary poorly absorbed, short‐chain carbohydrates increase delivery of water and fermentable substrates to the proximal colon. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:874–82.

Ong DK, Mitchell SB, Barrett JS, Shepherd SJ, Irving PM, Biesiekierski JR, et al. Manipulation of dietary short chain carbohydrates alters the pattern of gas production and genesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1366–73.

Lomer M, Parkes G, Sanderson J. Review article: lactose intolerance in clinical practice—myths and realities. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:93–103.

Gibson P, Newnham E, Barrett J, Shepherd S, Muir J. Review article: fructose malabsorption and the bigger picture. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:349–63.

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) and Commerce Commission of New Zealand: Warning and Advisory Statements and Declarations 2014, Standard 1.2.3—Mandatory Warning and Advisory Statements and Declarations.

Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, Rosella O, Muir JG, Gibson PR. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:320–328. e3. This research demonstrated that it was FODMAPs, and not gluten, which influenced symptoms of IBS.

Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:67–75. e5.

Halmos EP, Christophersen CT, Bird AR, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. Diets that differ in their FODMAP content alter the colonic luminal microenvironment. Gut. 2015;64:93–100. One of the only works to date demonstrating the impact of a low FODMAP diet on the microbiome.

Roberfroid M, Gibson GR, Hoyles L, McCartney AL, Rastall R, Rowland I, et al. Prebiotic effects: metabolic and health benefits. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:S1–63.

Macfarlane G, Steed H, Macfarlane S. Bacterial metabolism and health‐related effects of galacto‐oligosaccharides and other prebiotics. J Appl Microbiol. 2008;104:305–44.

Preidis GA, Versalovic J. Targeting the human microbiome with antibiotics, probiotics, and prebiotics: gastroenterology enters the metagenomics era. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2015–31.

Zhu Y, Zheng X, Cong Y, Chu H, Fried M, Dai N, et al. Bloating and distention in irritable bowel syndrome: the role of gas production and visceral sensation after lactose ingestion in a population with lactase deficiency. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1516–25.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by T32 DK07634 (WAW) from the National Institutes of Health. All authors have received research (LNK, CIJ) or educational (WAW) support from Nestlé Corporation.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

W. Asher Wolf received support from Nestlé, during and before the drafting of this article, to cover the cost of attendance at educational events and an academic conference.

Laszlo N. Kiraly has received compensation from the Nestlé Nutrition Institute for service as a faculty consultant for an educational fellowship, compensation from Metagenics for service on an advisory board, and compensation from Excited States LLC for service on a data and safety monitoring board.

Carol Ireton-Jones has received compensation from Nestlé for service as a consultant but did not collaborate with Dr. Wolf in any capacity related to Nestlé during the writing of this article.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Gastroenterology and Nutrition

Appendix

Appendix

FODMAP Basics

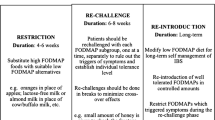

A FODMAP elimination diet is learning diet, not a permanent diet prescription. The object is to discover how changing certain sugars and fibers in your diet can help you manage your symptoms of gas, bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea and/or constipation; the eventual goal is the most nutritious and varied diet you can tolerate. It may be right for you if you have irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or a related condition and standard IBS therapy did not help.

The low-FODMAP diet can be tricky, since many kitchen staples and common food ingredients are off limits at first. It must be carefully planned to meet your nutrition needs. A registered dietitian nutritionist can help. This is especially important if you have other nutrition-related medical conditions.

Common high-FODMAP foods or ingredients | Popular low-FODMAP alternatives |

|---|---|

Regular milk, yogurt, or ice cream | Lactose-free versions of cow’s milk products, sorbet |

Cottage or ricotta cheese | Hard or aged cheeses; lactose-free cottage cheese |

Dried fruit, fruit juice, trail mix, fruit bars | Small portions of fresh or frozen fruit |

Apples, pears, stone fruits (cherries, peaches, prunes, apricots, avocados, mango), watermelon, blackberries | Strawberries, blueberries, cranberries, grapes, pineapple, cantaloupe, honeydew, kiwi, ripe bananas, oranges, lemons, limes |

Cauliflower, brussels sprouts, mushrooms, sweet corn, tomato paste, artichokes, asparagus, celery, beets | Spinach, kale, lettuce, fresh tomatoes, cucumber, carrots, zucchini, bell peppers, white potatoes. Small portions of green beans, peas, sweet potato, broccoli |

Wheat, barley or rye; breads, cereals, pastas or baked goods made of wheat, barley or rye; high-fiber bars or cereals | Rice, cornmeal, spelt or quinoa; breads, cereals, pastas or baked goods made of rice, cornmeal, millet, potatoes or quinoa; small portions of oats or buckwheat |

Sugar-free candy or gum sweetened with sorbitol, mannitol, maltitol, xylitol; milk chocolate | Small portions of sugar-sweetened candy, gum, or dark chocolate |

Canned, baked or refried beans (most varieties), edamame, hummus, soy milk | Firm tofu, tempeh, canned, drained chickpeas, or lentils |

Pistachios, cashews | Small portions of other nuts, nut butters, or seeds |

Garlic, onions, ketchup, commercial salad dressings | Garlic-infused oil, chives, scallion greens, leafy herbs, sweet spices, ginger, vinegars, mustards, lemon or lime juice |

Beverages, syrups, or condiments sweetened with high-fructose corn syrup (regular soda, bottled ice tea), honey, agave | Foods or beverages sweetened with granulated sugar, evaporated cane juice, brown sugar, 100 % pure maple syrup, brown rice syrup, stevia |

Rum, fortified wines | Small portions of beer, wine, gin, vodka, whiskey. Alcohol is a gut irritant, so consume in moderation |

Instant coffee, lattés, chamomile or fennel tea | Espresso, filtered coffee, green or peppermint tea. Caffeine is a gut irritant so consume in moderation |

FODMAP stands for fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols. FODMAPs are a group of poorly absorbed, fermentable carbohydrates that act together to produce gastrointestinal symptoms.

© 2015 Patsy Catsos, MS, RDN, LD, adapted from IBS—Free at Last! (Pond Cove Press). May be reproduced for patient education only. Reprinted with permission of Patsy Catsos, MS, RDN, LD.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wolf, W.A., Kiraly, L.N. & Ireton-Jones, C. Incorporating FODMAP Dietary Restrictions: Help or Hype?. Curr Nutr Rep 4, 214–219 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-015-0131-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-015-0131-9