Abstract

A diet low in poorly absorbed, fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) is now considered as an effective strategy for symptoms control in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The low FODMAP diet is administered in three phases, namely restriction of all dietary FODMAPs followed by rechallenge and then reintroduction of specific FODMAPs according to the tolerance of patients. A dietician should be involved in patients in whom a low FODMAP diet is planned. While restricting high FODMAPs, it is pertinent that patients are advised a well-balanced diet and suitable alternatives with low FODMAP contents in each food groups are prescribed. Strict adherence to a low FODMAP diet has been shown to improve symptoms, stool output, quality of life, and the overall well-being of patients with IBS. For those who do not respond to this dietary approach, a normal diet may be initiated and other treatment strategies (dietary or nondietary) should be considered. Interestingly, the low FODMAP diet has also been tried in other functional disorders, nonceliac gluten sensitivity, and even inflammatory bowel disease. Since the concept of FODMAP is relatively new, there is only limited data on the content of FODMAP in the Indian food items and there is a need to address this question. There is also a need for well-designed and adequately powered studies to explore the efficacy of low FODMAP diet in patients with IBS. In the present review article, we have compiled all the relevant information about FODMAPs with an objective to provide comprehensive information on FODMAPs to a physician.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: diagnosis and management. Clinical Guideline [CG61]. Published: February 2008. Last updated: April 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg61

Staudacher HM, Whelan K. The low FODMAP diet: recent advances in understanding its mechanisms and efficacy in IBS. Gut. 2017;66:1517–27.

Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:712–21.

Jamieson AE, Fletcher PC, Schneider MA. Seeking control through the determination of diet: a qualitative investigation of women with irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nurse Spec. 2007;21:152–60.

Ong DK, Mitchell SB, Barrett JS, et al. Manipulation of dietary short chain carbohydrates alters the pattern of gas production and genesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1366–73.

Barrett JS. How to institute the low-FODMAP diet. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32 Suppl 1:8–10.

Hayes PA, Fraher MH, Quigley EM. Irritable bowel syndrome: the role of food in pathogenesis and management. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;10:164–74.

Yang J, Deng Y, Chu H, et al. Prevalence and presentation of lactose intolerance and effects on dairy product intake in healthy subjects and patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:262–8.

Law D, Conklin J, Pimentel M. Lactose intolerance and the role of the lactose breath test. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1726–8.

Rosado JL, Solomons NW. Sensitivity and specificity of the hydrogen breath-analysis test for detecting malabsorption of physiological doses of lactose. Clin Chem. 1983;29:545–8.

Magge S, Lembo A. Low-FODMAP diet for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;8:739–45.

Nanayakkara WS, Skidmore PM, O’Brien L, Wilkinson TJ, Gearry RB. Efficacy of the low FODMAP diet for treating irritable bowel syndrome: the evidence to date. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:131–42.

Marcason W. What is the FODMAP diet? J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:1696.

Barrett JS, Gearry RB, Muir JG, et al. Dietary poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates increase delivery of water and fermentable substrates to the proximal colon. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:874–82.

Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–91.

Occhipinti K, Smith JW. Irritable bowel syndrome: a review and update. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2012;25:46–52.

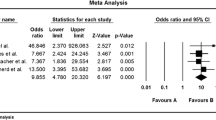

Marsh A, Eslick EM, Eslick GD. Does a diet low in FODMAPs reduce symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders? A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55:897–906.

O'keeffe M, Jansen C, Martin L, et al. Long-term impact of the low-FODMAP diet on gastrointestinal symptoms, dietary intake, patient acceptability, and healthcare utilization in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30:1–13.

Dionne J, Ford AC, Yuan Y, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the efficacy of a gluten-free diet and a low FODMAPS diet in treating symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:1290–300.

Staudacher HM, Lomer MC, Anderson JL, et al. Fermentable carbohydrate restriction reduces luminal bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Nutr. 2012;142:1510–8.

Pedersen N, Andersen NN, Végh Z, et al. Ehealth: low FODMAP diet vs Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16215–26.

Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:67–75.

Böhn L, Störsrud S, Liljebo T, et al. Diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome as well as traditional dietary advice: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1399–407.

Eswaran SL, Chey WD, Han-Markey T, Ball S, Jackson K. A randomized controlled trial comparing the low FODMAP diet vs. modified nice guidelines in US adults with IBS-D. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1824–32.

Hustoft TN, Hausken T, Ystad SO, et al. Effects of varying dietary content of fermentable short-chain carbohydrates on symptoms, fecal microenvironment, and cytokine profiles in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12969.

McIntosh K, Reed DE, Schneider T, et al. FODMAPs alter symptoms and the metabolome of patients with IBS: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2017;66:1241–51.

Staudacher HM, Lomer MC, Farquharson FM, et al. Diet low in FODMAPS reduces symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and probiotic restores bifidobacterium species: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:936–47.

Harvie RM, Chisholm AW, Bisanz JE, et al. Long-term irritable bowel syndrome symptom control with reintroduction of selected FODMAPs. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:4632–43.

Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, Rosella O, Muir JG, Gibson PR. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:320–8.

Priyanka P, Gayam S, Kupec JT. The role of a low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyol diet in non celiac gluten sensitivity. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2018;2018:1561476.

Biesiekierski JR, Iven J. Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity: piecing the puzzle together. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:160–5.

Halpin SJ, Ford AC. Prevalence of symptoms meeting criteria for irritable bowel syndrome in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1474–82.

Gearry RB, Irving PM, Barrett JS, Nathan DM, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Reduction of dietary poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates (FODMAPs) improves abdominal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease—a pilot study. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3:8–14.

Knight-Sepulveda K, Kais S, Santaolalla R, Abreu MT. Diet and inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;11:511–20.

Barrett JS, Gibson PR. Fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs) and nonallergic food intolerance: FODMAPs or food chemicals? Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2012;5:261–8.

Fasano A, Sapone A, Zevallos V, Schuppan D. Nonceliac gluten sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1195–204.

Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ. Personal view: food for thought—Western lifestyle and susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. The FODMAP hypothesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1399–409.

Gibson PR, Shepard SJ. Food choice as a key management strategy for functional gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:657–66.

Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ. Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: the FODMAP approach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:252–8.

National Institute of Nutrition. Dietary Guidelines for Indians. Hyderabad: National Institute of Nutrition. ICMR. 2011:86–91.

Gopalan C, Rama BV, Balasubramanian SC. Nutritive Value of Indian Foods. Hyderabad: National Institute of Nutrition, ICMR; 2004.

Longvah T, Ananthan R, Bhaskarachary K, Venkaiah K. Indian Food Composition Tables, 2017. Hyderabad: National Institute of Nutrition, ICMR; 2017.

Varney J, Barrett J, Scarlata K, Catsos P, Gibson PR, Muir JG. FODMAPs: food composition, defining cutoff values and international application. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:53–61.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines. 2013.

El-Salhy M, Gundersen D. Diet in irritable bowel syndrome. Nutr J. 2015;14:1–11.

Phillips W. When a registered dietitian becomes the patient: translating the science of the low FODMAP diet to daily living. Pract Gastroenterol. 2018;175:20–37.

Gibson PR, Barrett JS. Clinical ramifications of malabsorption of fructose and other short-chain carbohydrates. Pract Gastroenterol. 2007;31:51–65.

Barrett JS, Irving PM, Shepherd SJ, et al. Comparison of the prevalence of fructose and lactose malabsorption across chronic intestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:165–74.

Tuck C, Barrett J. Re-challenging FODMAPs: the low FODMAP diet phase two. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:11–5.

Staudacher HM, Whelan K, Irving PM, Lomer MC. Comparison of symptom response following advice for a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) versus standard dietary advice in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24:487–95.

Staudacher HM, Lomer MCE, Anderson JL, et al. Fermentable carbohydrate restriction impacts on luminal bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal symptoms in a randomized controlled trial of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Nutr. 2012;142:1510–8.

Vici G, Belli L, Biondi M, Polzonetti V. Gluten free diet and nutrient deficiencies: a review. Clin Nutr. 2016;35:1236–41.

Barton SH, Kelly DG, Murray JA. Nutritional deficiencies in celiac disease. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2007;36:93–108.

See J, Murray JA. Gluten-free diet: the medical and nutrition management of celiac disease. Nutr Clin Pract. 2006;21:1–15.

Catassi G, Lionetti E, Gatti S, Catassi C. The low FODMAP diet: many question marks for a catchy acronym. Nutrients. 2017;9:1–9.

Gröber U, Reichrath J, Holick MF. Live longer with vitamin D? Nutrients. 2015;7:1871–80.

Brewer MS. Natural antioxidants: sources, compounds, mechanisms of action, and potential applications. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2011;10:221–47.

Erickson J, Korczak R, Wang Q, Slavin J. Gastrointestinal tolerance of low FODMAP oral nutrition supplements in healthy human subjects: a randomized controlled trial. Nutr J. 2017;16:1–7.

Roest RD, Dobbs BR, Chapman BA, et al. The low FODMAP diet improves gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:895–903.

Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Fructose malabsorption and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: guidelines for effective dietary management. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:1631–9.

Barrett JS. Extending our knowledge of fermentable, short-chain carbohydrates for managing gastrointestinal symptoms. Nutr Clin Pract. 2013;28:300–6.

Maagaard L, Ankersen DV, Végh Z, et al. Follow-up of patients with functional bowel symptoms treated with a low FODMAP diet. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:4009–19.

Shepherd SJ, Lomer MC, Gibson PR. Short-chain carbohydrates and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:707–17.

Thompson T. Folate, iron, and dietary fiber contents of the gluten free diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:1389–96.

Caroline Tuck. Sprouting—does it reduce the FODMAP content of foods?. Monash University. (Uploaded on: 28.03.2017). Available from https://www.monashfodmap.com/blog/sprouting-does-it-reduce-fodmap-content/. Accessed 11 Jan 2019.

Koven NS, Abry A. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:385–94.

Wong Z, Mok CZ, Majid HA, Mahadeva S. Early experience with a low FODMAP diet in Asian patients with irritable bowel syndrome. JGH Open. 2018;2:178–81.

Hewawasam SP, Iacovou M, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Dietary practices and FODMAPs in South Asia: applicability of the low FODMAP diet to patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:365–74.

Iacovou M, Tan V, Muir JG, Gibson PR. The low FODMAP diet and its application in East and Southeast Asia. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 2015;21:459–70.

Funding

Wajiha Mehtab acknowledges the University Grants Commission for support of her fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

WM, AA, NS, AM, and GKM declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The authors are solely responsible for the data and the contents of the paper. In no way, the Honorary Editor-in-Chief, Editorial Board Members, or the printer/publishers are responsible for the results/findings and content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mehtab, W., Agarwal, A., Singh, N. et al. All that a physician should know about FODMAPs. Indian J Gastroenterol 38, 378–390 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12664-019-01002-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12664-019-01002-0