Abstract

For degradation of sugarcane bagasse (SCB), several enzymes are needed but β-glucosidase is rate limiting in cellulose hydrolysis. Since different microorganisms synthetize characteristic pool of enzymes, mixing extracts produced by different species may increase hydrolytic efficiency due to synergism between enzymes in cocktails. This paper reports the study of β-glucosidase production in solid state cultivation (SSC) of two filamentous fungi, thermophilic Thermoascus aurantiacus and mesophilic Trichoderma reesei, and application of the enzymatic extracts on non-pretreated SCB saccharification. Enzyme extract obtained from the thermophilic fungus presented higher β-glucosidase and FPU activities (1.8 U/mL and 10 FPU/mL) than the one from mesophilic (0.2 U/mL and 6 FPU/mL). Optimal SCB hydrolysis was achieved when applying enzymatic cocktail composed of equal volumes of both fungal extracts (3.6 FPU/gSCB, filter paper units per gram SCB, 2.25 FPU/gSCB provided by extract from T. aurantiacus and 1.35 FPU/gSCB from T. reesei) at 65 °C. The hydrolysis yield applying the enzyme cocktail, 124 mg total reducing sugars (TRS) per gSCB, was higher than any yield achieved when using the enzyme extracts separately (105 mgTRS/gSCB using 12.5 FPU per gSCB from T. aurantiacus at 65 °C; 79 mgTRS/gSCB using 7.5 FPU per gSCB from T. reesei at 45 °C). Therefore, the use of the cocktail (3.6 FPU/gSCB) at 65 °C released 18 and 57% more TRS respectively than when extracts from T. aurantiacus or from T. reesei were applied alone, respectively, even reducing enzyme load (FPU) by 70%, corroborating the synergistic effect when both extracts are used together.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

OECD/IEA (2010) Sustainable production of second-generation biofuels. https://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/second_generation_biofuels.pdf. Accessed 23 June 2017

Jeon YJ, Xun Z, Rogers PL (2010) Comparative evaluations of cellulosic raw materials for second generation bioethanol production. Lett Appl Microbiol 51:518–524. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02923.x

UNICA (2018) União da Indústria de Cana-de-Açúcar. https://www.unicadata.com.br/historico-de-producao-e-moagem.php. Accessed 05 Aug 2018

Mishima D, Tateda M, Ike M, Fujita M (2006) Comparative study on chemical pretreatments to accelerate enzymatic hydrolysis of aquatic macrophyte biomass used in water purification processes. Bioresour Technol 97:2166–2172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2005.09.029

Kaschuk JJ, Santos DA, Frollini E, Canduri F, Porto ALM (2019) Influence of pH, temperature, and sisal pulp on the production of cellulases from Aspergillus sp. CBMAI 1198 and hydrolysis of cellulosic materials with different hemicelluloses content, crystallinity, and average molar mass. Biomass Conv Bioref 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-019-00440-2

Pandey A (2003) Solid-state fermentation. Biochem Eng J 13:81–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1369-703X(02)00121-3

Pandey A, Soccol CR, Mitchell D (2000) New developments in solid state fermentation: I-bioprocesses and products. Process Biochem 35:1153–1169. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-9592(00)00152-7

Desgranges C, Vergoignan C, Georges M, Durand A (1991) Biomass estimation in solid state fermentation. 1. Manual biochemical methods. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 35:200–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00184687

Jiang B, Tsao R, Li Y, Miao M (2014) Food safety: food analysis technologies/techniques. In: Van Alfen NK (ed) Encyclopedia of Agriculture and Food Systems, 2nd edn. Academic Press, pp 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-52512-3.00052-8

Florencio C, Badino AC, Farinas CS (2017) Desafios relacionados à produção e aplicação das enzimas celulolíticas na hidrólise da biomassa lignocelulósica. Quim Nova 40:1082–1093. https://doi.org/10.21577/0100-4042.20170104

Sørensen HR, Pedersen S, Jørgensen CT, Meyer AS (2007) Enzymatic hydrolysis of wheat arabinoxylan by a recombinant “minimal” enzyme cocktail containing beta-xylosidase and novel endo-1, 4-beta-xylanase and alpha-l-arabinofuranosidase activities. Biotechnol Prog 23:100–107. https://doi.org/10.1021/bp0601701

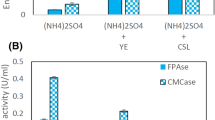

Da Silva R, Lago ES, Merheb CW, Macchione MM, Park YK (2005) Production of xylanase and CMCase on solid state fermentation in different residues by Thermoascus aurantiacus Miehe. Braz J Microbiol 36:235–241. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-83822005000300006

McClendon SD, Batth T, Petzold CJ, Adams PD, Simmons BA, Singer SW (2012) Thermoascus aurantiacus is a promising source of enzymes for biomass deconstruction under thermophilic conditions. Biotechnol Biofuels 5:54. https://doi.org/10.1186/1754-6834-5-54

Zanelato AI, Shiota VM, Gomes E, Thoméo JC (2012) Endoglucanase production with the newly isolated Myceliophtora sp. i-1d3b in a packed bed solid state fermentor. Braz J Microbiol 43:1536–1544. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-83822012000400038

Ghose TK (1987) Measurement of cellulase activities. Pure Appl Chem 59:257–268. https://doi.org/10.1351/pac198759020257

Miller GL (1959) Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal Chem 31:426–428. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac60147a030

Leite RSR, Alves-Prado HF, Cabral H, Pagnocca FC, Gomes E, Da Silva R (2008) Production and characteristics comparison of crude β-glucosidases produced by microorganisms Thermoascus aurantiacus e Aureobasidium pullulans in agricultural wastes. Enzym Microb Technol 43:391–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enzmictec.2008.07.006

Viccini G, Mitchell DA, Boit SD, Gern JC, da Rosa AS, Costa RM, Dalsenter FDH, Von Meien OF, Krieger N (2001) Analysis of growth kinetic profiles in solid-state fermentation. Food Technol Biotechnol 39:271–294

Perrone OM, Colombari FM, Rossi JS, Moretti MMS, Bordignon SE, Nunes CCC, Gomes E, Boscolo M, Da Silva R (2016) Ozonolysis combined with ultrasound as a pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse: effect on the enzymatic saccharification and the physical and chemical characteristics of the substrate. Bioresour Technol 218:69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2016.06.072

Casciatori FP, Laurentino CL, Taboga SR, Casciatori PA, Thoméo JC (2014) Structural properties of beds packed with agro-industrial solid by-products applicable for solid-state fermentation: experimental data and effects on process performance. Chem Eng J 255:214–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2014.06.040

Grajek W (1987a) Comparative studies on the production of cellulases by thermophilic fungi in submerged and solid state fermentation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 26:126–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00253895

Pinto TOP (2010) Cellulolytic enzymes production by fungi Thermoascus aurantiacus CBMAI 756, Thermomyces lanuginosus, Trichoderma reesei QM9414 and Penicillium viridicatum RFC3 and application in saccharification of sugarcane bagasse with different pretreatments. Dissertation, São Paulo State University

Gomes E, Umsza-Guez MA, Martin N, Silva R (2007) Enzimas termoestáveis: fontes, produção e aplicação industrial. Quim Nova 30:136–145. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-40422007000100025

De Cassia PJ, Paganini Marques N, Rodrigues A, Brito de Oliveira T, Boscolo M, Da Silva R, Gomes E, Bocchini Martins DA (2015) Thermophilic fungi as new sources for production of cellulases and xylanases with potential use in sugarcane bagasse saccharification. J Appl Microbiol 118:928–939. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.12757

Grajek W (1986) Temperature and pH optimum of enzyme activities produced by cellulolytic thermophilic fungi in batch and solid-state celulases. Biotechnol Lett 8:587–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01028089

Grajek W (1987b) Production of D-xylanases by thermophilic fungi using different methods of culture. Biotechnol Lett 9:353–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01025803

Palma MB (2003) Xylanases production by Thermoascus aurantiacus in solid statecultivation. Thesis, Federal University of Santa Catarina

Kalogeris E, Christakopoulos P, Katapodis P, Alexiou A, Vlachou S, Kekos D, Macris BJ (2003a) Production and characterization of cellulolytic enzymes from the thermophilic fungus Thermoascus aurantiacus under solid state cultivation of agricultural wastes. Process Biochem 38:1099–1104. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-9592(02)00242-X

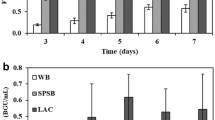

Smits JP, Rinzema A, Tramper J, Van Sonsbeek HM, Knol W (1996) Solid-state fermentation of wheat bran by Trichoderma reesei QM9414: substrate composition changes, C balance, enzyme production, growth and kinetics. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 46:489–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002530050849

Kalogeris E, Iniotaki F, Topakas E, Christakopoulos P, Kekos D, Macris BJ (2003b) Performance of an intermittent agitation rotating drum type bioreactor for solid-state fermentation of wheat straw. Bioresour Technol 86:207–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-8524(02)00175-X

Basso TP, Gallo CR, Basso LC (2010) Atividade celulolítica de fungos isolados de bagaço de cana-de-açúcar e madeira em decomposição. Rev Agropec Bras 45:1282–1289. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-204X2010001100008

King BC, Donnelly MK, Bergstrom GC, Walker LP, Gibson DM (2009) An optimized microplate assay system for quantitative evaluation of plant cell wall-degrading enzyme activity of fungal culture extracts. Biotechnol Bioeng 102:1033–1044. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.22151

Kovács K, Szakacs G, Zacchi G (2009) Comparative enzymatic hydrolysis of pretreated spruce by supernatants, whole fermentation broths and washed mycelia of Trichoderma reesei and Trichoderma atroviride. Bioresour Technol 100:1350–1357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2008.08.006

Moretti MMS, Bocchini-Martins DA, Nunes CCC, Villena MA, Perrone OM, Da Silva R, Boscolo M, Gomes E (2014) Pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse with microwaves irradiation and its effects on the structure and on enzymatic hydrolysis. Appl Energy 122:189–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.02.020

Margeot A, Hahn-Hagerdal B, Edlund M, Slade R, Monot F (2009) New improvements for lignocellulosic ethanol. Curr Opin Biotechnol 20:372–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2009.05.009

Lynd LR, Weimer PJ, Zyl WH, Pretorius IS (2002) Microbial cellulose utilization: fundamentals and biotechnology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 66:506–577. https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.66.3.506-577.2002

Jung S, Song Y, Kim HM, Bae HJ (2015) Enhanced lignocellulosic biomass hydrolysis by oxidative lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMOs) GH61 from Gloeophyllum trabeum. Enzym Microb Technol 77:38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enzmictec.2015.05.006

Ezeilo UR, Zakaria II, Huyop F, Wahab RA (2017) Enzymatic breakdown of lignocellulosic biomass: the role of glycosyl hydrolases and lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip 31:647–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/13102818.2017.1330124

Bi S, Peng L, Chen K, Zhu Z (2016) Enhanced enzymatic saccharification of sugarcane bagasse pretreated by combining O2 and NaOH. Bioresour Technol 214:692–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2016.05.041

Lopes AM, Ferreira Filho EX, Moreira LRS (2018) An update on enzymatic cocktails for lignocellulose breakdown. J Appl Microbiol 125:632–645. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.13923

Braga CMP, Delabona PDS, Lima DJDS, Paixão DAA, Pradella JGDC, Farinas CS (2014) Addition of feruloyl esterase and xylanase produced onsite improves sugarcane bagasse hydrolysis. Bioresour Technol 170:316–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.07.115

Arias JM, Modesto LFA, Polikarpov I, Pereira-Jr N (2016) Design of an enzyme cocktail consisting of different fungal platforms for efficient hydrolysis of sugarcane bagasse: optimization and synergism studies. Biotechnol Prog 32:1222–1229. https://doi.org/10.1002/btpr.2306

Bussamra BC, Freitas S, Costa AC (2015) Improvement on sugar cane bagasse hydrolysis using enzymatic mixture designed cocktail. Bioresour Technol 187:173–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2015.03.117

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Council for the Improvement of Higher Education (CAPES) and the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) for their financial support and scholarships [grant numbers 2010/12624-0, 2011/21239-6, 2011/07453-5, 2012/02768-0, 2013/01756-1, 2017/16482-5, 2018/00996-2] and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPQ) [grant number 426578/2016-3].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Highlights

• Thermophilic fungus yielded more β-glucosidase than the mesophilic one, in a shorter time;

• Fungal biomass was well estimated based on total protein content by the Kjeldahl method;

• β-Glucosidase activity production was strongly and directly associated with fungal growth;

• Enzymes in cocktail have a synergistic effect on the hydrolysis of sugarcane bagasse.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frassatto, P.A.C., Casciatori, F.P., Thoméo, J.C. et al. β-Glucosidase production by Trichoderma reesei and Thermoascus aurantiacus by solid state cultivation and application of enzymatic cocktail for saccharification of sugarcane bagasse. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 11, 503–513 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-020-00608-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-020-00608-1