Abstract

This paper draws on survey and interview data with public school principals, in order to examine the impact of philanthropy in public schools in Australia. As a result of systemic government funding deficits, school principals are applying for competitive grants from a diverse range of sources. This includes non-government organisations such as charities and businesses, as well as competitive government grants to pay for important resourcing in the school. We focus on what we refer to as ‘philanthropic grant chasing’ in public schools as reported by school principals, paying attention to their involvement with the registered charity Australian Schools Plus, one of the first government-subsidised charities that enables businesses and corporations to donate to public schools for a tax deduction. Public school principals expressed dilemmas and ambivalences regarding philanthropy, regarding it as a ‘double-edged sword’. The vast majority rejected the idea of philanthropy as a long-term solution or remedy for systemic issues of under-funding. We found that philanthropic grants were conditional, and imposed excessive accountability and performative measures on principals, with interviewees describing the process as onerous, with ‘too many strings attached’. Competitive philanthropic grants were also found to intensify principal workload. This paper points to how competitive philanthropic grants, and the necessity to generate additional funding, has a detrimental impact on leaders’ workload, time, and long-term school resourcing. It is remodelling the expertise of the principal to grant chaser and revenue raiser. Whilst philanthropic organisations frequently claim otherwise, we argue that philanthropy exacerbates rather than redresses educational equity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Daniel: Generating more funds is definitely part of my core work… because to deliver what we want to deliver for our school and what our school community wants, you definitely have to do it. Yeah, you can’t rely on just what you’re… what you’re given [from the government]. (Daniel, Principal Secondary School Queensland, Disadvantaged Cohort)

This paper draws on survey and interview data with public school principals in order to examine the impact of philanthropy and philanthropic competitive grants in public schools in Australia. Due to systemic funding deficits, school principals are applying for competitive grants from a diverse range of sources, including non-government sources (philanthropy, charities, businesses), in addition to competitive grants from the government to pay for a range of resources including student wellbeing programs, library resources, or school building infrastructure. In this paper, we specifically examine public school principals’ experiences in philanthropic grant chasing and revenue raising, paying attention to charity Australian Schools Plus.

We argue that philanthropic funding, when coupled with systemic under-funding and accountability practices, contributes to educational inequities. Philanthropic logics, and the notion of public schools competing and ‘winning’ scarce funds, points to dangerous power shifts and imbalances, particularly when positioned in a context of marketisation of public schools (Kenway et al., 1993; Le Feuvre et al., 2023; Windle, 2009), unsustainable workloads for principals (McKay et al., 2022), and increasing logics of performative accountability (Lingard et al., 2017), in contrast with forms of ‘intelligent accountability’ (Mockler and Stacey, 2021).

To this end, a proportion of the analysis focuses on participants’ engagement with Australian Schools Plus, an organisation that was the first of its kind in Australia for enabling high-wealth individuals, corporations and businesses to donate to public schools for a tax deduction. As Schools Plus is a relatively recent initiative, there have been limited studies that have focused on how the organisation has impacted public schools (see Hogan et al., 2023; Rowe, 2023), and we take up Hogan et al.’s (2023) suggestion that:

With tax-deductible charitable/philanthropic donations only just made allowable in public schools in Australia with the advent of Schools Plus, it is fair to say that there is considerable need for further research on its practices and effects. (Hogan et al., 2023, p. 776).

This paper seeks to raise questions about the limitations of philanthropy and systemic impacts for public schools that accompany philanthropic grants. It is here that the major contribution of this paper lies, offering insights into the ways in which principals are required to ‘perform’ the entrepreneurial, enterprising and accountability cultures engendered by philanthropic organisations in Australia. Or, put plainly, how these cultures are translated into the everyday experiences of principals and school leaders seeking philanthropic support.

This paper will be structured as follows: the next section discusses philanthropy in public education, endeavouring to position this within a broader globalised context, before turning to focus on the national, explaining Schools Plus, and how government-subsidised philanthropy occurs in tandem with the under-funding of public schools. Subsequently, the paper explains the methodology before analysing the data.

Philanthropy in public education

‘Philanthropy’ tends to be used as a type of shorthand in public debates and discussions, undoubtedly for its positive connotations; although, ‘philanthropy’ is incredibly diverse in its make-up and involvement in public life (Hogan and Williamson, 2022). Philanthropy includes a spectrum of political interests and encompasses many left-wing movements, such as climate change movements, same-sex marriage debates and advocating against unfair employment practices. Therefore, the reference to ‘philanthropy’ is problematic in some respects (McGoey et al., 2018), for it is simplified shorthand referencing a highly diverse landscape, including a spectrum of political interests. In this respect, the paper is interested in business and corporate philanthropy, sometimes referred to as ‘new’ philanthropy and philanthrocapitalism (Ball et al., 2017), in addition to private flows of money into public schools (Jobér, 2023; Reikosky, 2023).

Philanthrocapitalism seeks to bring the business world into the philanthropic world, and ‘the belief that marrying corporate profits with social welfare can lead to general prosperity’ (McGoey et al., 2018, p. 3), underlined by the credence of market superiority. McGoey (2015) and Reich (2018) argue that the linking of philanthropy with corporate business interests drives and exacerbates broader societal inequity, rather than redressing and improving equity, as philanthrocapitalists often claim to do. In her work that centres upon the Gates Foundation, McGoey (2015) examines how the Gates Foundation has utilised donations to build unprecedented political leverage in education in the United States, mobilising nation-wide education reforms, such as charter schools, the small schools initiative or advancing the Common Core Curriculum Standards, and teacher accountability measures (Au et al., 2017; Fontdevila et al., 2021; Reckhow, 2013; Tompkins-Stange, 2016).

However, unlike the United States, where venture philanthropic organisations, such as the Gates Foundation, are criticised in mainstream debatesFootnote 1 (e.g. LA Times, 2023), there is scope for further critique of these organisations and their engagement or role in public education, and to a greater extent in mainstream public debates in Australia. For instance, in their study of media reporting of Teach For Australia, the authors found that the organisation had benefited from largely positive media coverage (Chan et al., 2022). Furthermore, our critique is timely and relevant, with philanthropy being bolstered in legislation at the time of writing, such as the government’s ‘doubling philanthropy’ initiative and tying this to major social services (Philanthropy Australia, 2023a; Productivity Commission, 2023).

The risks of philanthropic funding in public schools is that it can be a vehicle for profit-making, product placement and political leveraging; utilised as a tool to advance private interests, serving to augment commercial or business interests (Hogan et al., 2023), corporate profit-making and embedding products into schools (Reikosky, 2023; Rowe et al., 2024), wielding policy influence (Reckhow, 2013; Tompkins-Stange, 2016) and the privatisation of policy-making (Au et al., 2017; Lubienski, 2016). Power is increasingly shifted towards third-sector actors (Kolleck, 2019). Indeed, philanthropy is not simply a matter of ‘money’ (though money is clearly important)—it also concerns significant shifts of power and policy influence, as it is increasingly evident how philanthropy can ‘purchase’ a role at the education policy-making table (Au et al., 2017; Saltman, 2010; Tompkins-Stange, 2016).

Australian Schools Plus: government-subsidised philanthropy

Australian Schools Plus was established following recommendations within the Australian Government Review of Funding (colloquially referred to as the Gonski Report) (Australian Government, 2011). This report advocated for the introduction of philanthropy within public education (Gerrard et al., 2017; Savage, 2016) and importantly, this would be government-subsidised philanthropy (Schools Plus receives annual funding from the federal government). As is common within these networks, an author of these reforms claims that philanthropy should not replace government funding, and rather supplement government funding (Gonski, 2016), which tends to function as a reductive argument.

As a registered charity since 2013, Schools Plus is well-connected within elite philanthropic networks of influence, albeit it is only one organisation amongst many (Rowe, 2022b, 2023). Australia’s peak venture philanthropic organisation, Social Ventures Australia, which was modelled on the Gates Foundation (Traill, 2016), maintained a leading role in establishing Schools Plus, and their former CEO Michael Traill was the first CEO of Schools Plus (Traill now sits on the board of the Paul Ramsay Foundation, amongst many others). Nevertheless, it is only one amongst many highly influential registered charities working in public education in Australia, and in comparison to other government-subsidised registered charities, their annual government funding is relatively low (e.g. Berry Street Victoria Incorporated reported 151 million annual government funding; Teach For Australia reported 13 million annual government fundingFootnote 2). Schools Plus reported $720,000 government funding in the last financial year, according to current financial data available (ACNC, 2023, 2024a, 2024b).

Schools Plus’s purported aim is to provide a type of brokerage and ‘bridge between businesses and schools’ (interview with Schools Plus senior, 2020), to enable businesses to donate money to public schools for a tax deduction. In order to receive a grant from Schools Plus, a school must be categorised as disadvantaged according to the Index of Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA). In their impact report, Schools Plus state they have supported one in four disadvantaged public schools in Australia, which are eligible for funding (Schools Plus, 2023a), which equates to approximately 13% of schools nationally. In practice, this means that the majority of disadvantaged schools have not received funding from Schools Plus. Furthermore, the majority of schools that have received Schools Plus funding are located in New South Wales, followed by Victoria (Schools Plus, 2023a).

Since 2015, Schools Plus has reportedly raised 36 million (Schools Plus, 2023a), mainly from corporations, high-wealth individuals and foundations (Hogan et al., 2023). Google granted Schools Plus a high profile grant in 2023, which received positive media coverage (Philanthropy Australia, 2023b). This 36 million represents money diverted from public taxation, which theoretically would benefit public schools as well (but without the competitive applications). The money that is raised is not distributed directly to schools, but rather filtered through the organisation itself to pay for additional costs such as marketing, staff salaries and so forth. Their financial records indicate that approximately 66% of their donations are distributed to schools (ACNC, 2024c).

On one hand, Schools Plus is a positive move within a competitive market that enables private schools to leverage significant income through investments, bequeaths and donations. So too, due to their charitable status, private schools receive generous tax-exemptions, whereas public schools do not. Schools Plus theoretically enables public schools to compete and leverage financial donations from businesses or corporations. On the other hand, it is coupled with limitations and risks, such as incremental withdrawal of government funding for public schools, compelling public school principals to be entrepreneurial in generating additional funds and requiring time-intensive applications. The philanthropic grants impose further accountability measures including writing reports, attending meetings and undertaking coaching sessions, which we subsequently discuss. Before doing so, we examine an important context in which philanthropic grant chasing occurs, which is the systemic under-funding of Australian public schools.

Systemic under-funding of public schools

In Australia, public schools, also referred to as government or state schools, receive the majority of their funding from their respective state or territory government; and private or non-government schools receive the majority of their funding from the Commonwealth or Federal government (Australian Government, 2024). This funding is accompanied by relatively minor ‘strings attached’ for private schools, including mandated expectations to implement the Australian Curriculum, participate in standardised testing and report data to the government (Australian Government, 2018). There is no government regulation regarding tuition fees (how much a school can charge) and student enrolment processes (selection).

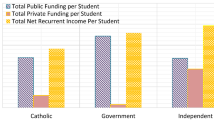

Schools receive different types of funding, including recurrent funding (the Schooling Resource Standard or SRS), capital funding (e.g. school infrastructure) and private sources (e.g., tuition fees, donations). Despite it theoretically being ‘needs-based’, most public schools are not currently funded to the minimum standard as stipulated in the SRS. The majority of states and territories are not meeting the agreed funding targets for public schools, while targets are being met or exceeded for private schools (Beazley, 2023; Beazley and Cassidy, 2023; Preston, 2023; Rorris, 2023). In the state of Victoria for example, it was estimated in government briefings that public schools were only receiving 90.43% of their SRS, whereas private schools were exceeding their SRS funding target (102.50%). This is a similar pattern reflected across all states/territories except for the Australian Capital TerritoryFootnote 3 (Beazley, 2023; Rorris, 2023).

The under-funding of public schools over the last decade has reportedly been enabled via special deals and accounting loopholes (Rorris, 2021; Wark, 2024) made possible by the election of a more conservative federal government in 2013. The newly elected government enabled states/territories to include capital depreciation within their funding targets, which undermines actual funding, particularly the Schooling Resource Standard (Rorris, 2023). But capital funding is equally diluted and weakened for public schools, with private schools receiving a greater amount of capital funding, due to being able to access two sources of capital funding (federal and state), whereas public schools historically have only been able to acquire capital funding from the states (single year federal capital funding has recently been introduced for public schools at time of writing) (AEU, 2024). Economist Rorris (2023) estimates a cumulative under-funding impact of billions of dollars for public schools.

The under-funding of public schools represents a significant driver of social inequity, and is detrimental to the resourcing of public schools and learning environments (OECD, 2016), and contributes to increased workload, time poverty and work intensification (Creagh et al., 2023; McKay et al., 2022). We would certainly argue that within the study, the labour in producing more funding within the school increased school principal workload, fundamentally changing the role of school leaders into grant chasers and revenue raisers.

Methodology

This paper draws on survey data in addition to in-depth interviews with public school principals, located in Queensland, Victoria, New South Wales and the Northern Territory. The paper forms part of a broader long-term study about venture philanthropy in public education (2020–2024), which includes a total of 45 interviews at time of writing, 10 days of fieldnotes in addition to policy network mapping (see Rowe et al., 2024 Rowe, 2022a, 2022c, 2023). This paper references one of these interviews, carried out with a senior Schools Plus representative in 2020. A focus on competitive grants from government sources are explored elsewhere (see, Rowe & Langman, 2024).

The online cross-sectional survey was designed with the assistance of Dr. Mark Rahimi, and subsequently piloted with a small number of principals in May–June 2023, followed by a distributed invitation on social media to public school principals, including deputy/assistants (July–November 2023). The title of the survey was, ‘How does philanthropy impact your working life and your school?’ and consisted of multiple-choice, short answers, and Likert scale questions to inquire into principals’ attitudes, beliefs, opinions or practices in regard to philanthropic grants in their schools (Creswell, 2012). For example, a Likert scale was used to ask survey respondents to respond to a series of statements (see Fig. 1):

The survey received 191 responses, but only 143 were completed or near-completed (only missing between 1–2 questions) and are included within the data analysis. As the survey asked respondents for the name of their school, the School Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (hereby referred to as ICSEA) was manually recorded for each school after the completion of the survey, enabling us to capture socio-demographics for each respondent. Survey respondents represented both primary, secondary and combined schools (see Table 1):

The survey asked respondents if they would agree to an in-depth interview via Zoom, and subsequently 18 interviews were undertaken with public school principals from July to November 2023. The interview participants are shown on the table below (see Table 2):

The survey respondents and interviewees represent diverse school locations (cities, regional and remote) and a range of school socioeconomic status (SES) contexts, including advantaged and disadvantaged school cohorts. The school ICSEA is used as a proxy for school socio-economic status, with values lower than 1000 indicating a school cohort that is categorised as disadvantaged (based on parent occupation and education levels, in addition to school-level data) (ACARA, 2019, 2024).

In one section of data analysis, we focus on the interview participants’ experiences with Schools Plus. From the interview participants, only three public school principals had received grants from Schools Plus (which is unsurprising given that we only interviewed a small number of school principals). Therefore, this is limited in scope but arguably it is important. As mentioned, Schools Plus is a relatively recent initiative, thus there have been limited studies that have focused on the organisation, as a policy network (Rowe, 2023) or as a policy solution (Hogan et al., 2023). Hogan et al.’s (2023) study equally drew on three interview participants.

The majority of interviewees had not heard of Schools Plus, which represents a paradox; whilst we argue that organisations such as Schools Plus are impacting public school principals in terms of creating systemic incentives for competitive, market-like generation of funding, organisations such as these arguably maintain little impact for many principals in their day-to-day lives; and, are highly ineffective for wrestling with the contextual realities of school principals (Thomson, 2000), and addressing the tangible, systemic impacts of deficit models of funding.

Philanthropic funding: a double-edged sword in the context of under-funding

There are other things I could be doing rather than [writing applications for funding], but it’s sort of part of the job I suppose. You try and source money from wherever you can. (Mark, primary school principal. 4th August 2023)

There was a strong perception from both the survey respondents and the interviewees that overall, there is an increase on competitive funding, and the emphasis or expectation to generate additional funding outside of their ‘core’ or regular funding from the Department (the government) has incrementally increased. When asking Mark whether generating additional funds through philanthropy was another skill-set he needed to have, he responded quite emphatically in the affirmative:

Yes, yes… definitely.

(Mark, primary school principal. 4th August 2023)

Many public school principals conceptualised their labour in generating additional funds, outside of their regular budget, as ‘part of their job’. On one hand, interviewed school principals enjoyed building relationships with local businesses, or the flexibility to pursue a passion project and small grants, but when anchored in significant funding deficits and lengthy applications, this added time pressure points and stresses. This is reflected in work intensification literature, such as Creagh et al.’s (2023) review of existing research, who write that for school leaders, workload is intensified when an already heavy workload ‘is translated into multiple competing priorities’ (p. 11).

Philanthropic grants provoked ambivalences and dilemmas for public school principals. On one hand, the majority of survey respondents (76%) agreed or totally agreed with the statement that ‘philanthropy is a much-needed injection of funds in my school’, and only 9% disagreed or totally disagreed (the remaining proportion were undecided). But so too, 58% of respondents agreed/totally agreed that ‘applying for philanthropic grants is a distraction from the more important professional jobs that I have’ (22% disagreed/totally disagreed; 20% undecided). This was a common theme throughout the survey responses and interviews; many participants regarded it as ‘necessary’, which spoke to the need for more funding and resources, but the applications clearly came at a cost for school leaders. One of these costs is the way in which philanthropic funding applications shape their role, expertise, attention and time, with one survey respondent writing: ‘too much time is wasted on writing unsuccessful applications’.

Whilst there were dilemmas when it came to the role of philanthropy in their schools, there was no such ambivalence when it came to whether philanthropy offered a long-term or sustainable solution for public education funding. The majority of respondents (89%) agreed/totally agreed that ‘philanthropy does not fix the systemic issues of under-funding’ (7% disagreed/totally disagreed) and 82% agreed/totally agreed that ‘philanthropy is a short-term fix to systemic under-funding’ (9% disagreed/totally disagreed).

The magnitude of philanthropic funding

The survey data indicated a relatively significant sum of philanthropic money was brought into public schools and from the survey responses, it was estimated that a total of 3.4 million was brought into schools within one year. However, this was undoubtedly a rushed estimate by survey respondents, and we treated this data cautiously. The average amount of money brought into the school through philanthropic funding in one year was estimated as $25,065 (primary school principal) to $38,045 (secondary school principal).

The majority of interviewees, when questioned about their individual sum, felt that the amount was under-estimated, rather than over-estimated. Therefore, the utility of this data, regarding how much money is brought into public schools through philanthropic dollars, might be best acquired in terms of capturing a crowded landscape of competitive grants and funders. Principals are busy applying for competitive grants from a range of sources.

The following section pays attention to school principals’ engagement with Schools Plus, a government-subsidised registered charity which provides competitive (conditional) grants to public schools.

Winners and losers in the philanthropy lottery: auditing, accountability and answerability

We are a low socioeconomic school… Money is tight for us, you know. And when we got $20,000 from [Schools Plus]—we thought, ‘Wow, this is wonderful. This is manna from heaven’. (Luke, secondary school principal, 16th August 2023).

The drive for philanthropic funding from organisations such as Schools Plus is anchored within funding deficits, shortfalls and significant government under-funding for public schools. Luke, a public school principal from a secondary school, discusses how his school received a $20,000 funding grant from Schools Plus and discusses it in relation to his school’s budgetary position (‘money is tight for us’), and when receiving the Schools Plus grant, described it as ‘manna from heaven’.

This was a common theme across the interviews when it came to eliciting competitive philanthropic grants. Participants valued the money that was donated to the school, since it came from a sense of scrambling for dollars. Many principals spoke about ‘scrimping and saving’. But there are costs involved for the school principals, which certainly would maintain flow-on impacts to teachers and students. Luke captures some of these costs:

They wanted too much… [Schools Plus] were by far the most onerous mob we’ve ever worked with. And I’ve told other principals, ‘You’d be crazy to go with that’. (Luke, secondary school principal, 16th August 2023)

For the interviewees, philanthropic granters were imposing excessive accountability practices onto principals, with Luke describing it as onerous and ‘terrible’:

[Schools Plus] were terrible… Look, they benefitted us 20 grand. But as I gave the feedback to them in fairly brutal terms, it was such an onerous experience. It was so … I’ll never touch them again no matter how desperate I am. (Luke, secondary school principal, 16th August 2023)

Therefore, whilst he initially described it as ‘manna from heaven’, he also emphasised that he would not ‘touch them again’, due to stringent auditing requirements and accountability measures. Similar themes were echoed by Ryan, a primary school principal who describes himself as a diligent grant writer, stating that when he first became principal, he ‘applied for every grant that came across my desk’ (Ryan, Interview, 17th August 2023). However, he expresses cynicism from the seemingly endless process of applying for competitive grants, a process in which unsuccessful grants do not receive feedback; now he regards himself as more ‘selective’, due to time-constraints and ‘grant fatigue’. This is a common sentiment amongst the principals, who describe numerous applications, including Schools Plus, as time-consuming.

Ryan applied to Schools Plus three times before he was successful, winning a grant worth $20,000 that he was using for a wellbeing program in his school. He says he wrote the grant in the evening, sitting at his kitchen table, and wrote ‘late into the night’ (Interview). As part of the conditions of the grant, Ryan had to attend three coaching sessions per year, each timed at three hours each and at the end of his working day, extending into the evenings. He says,

So I mean it’s not going to kill me but it’s sort of interview style. Each person, each school gets a chance to explain what they’re doing and we have to say is it effective, what are the benefits etcetera. I’m not sure anybody gets anything out of it. Everyone says they do because that’s the polite thing to say.

I certainly don’t [get anything out of it] but [this reflects my school team]. We have got a really strong team here [at the school], who have put a lot of thought and effort into this and we’re constantly reflecting [on our approach].

So maybe the other schools [get something out of it] … it is an opportunity for them to reflect but I just find it a bit of a… a waste of my time, I think.

(Ryan, primary school principal, 17th August 2023)

Ryan’s experience reflects how a high degree of performative accountability is built into the process and functionality of applying for (and winning) philanthropic grants. Lingard et al. (2017) write that ‘accountability can be understood in two senses: (1) being held to account; and (2) giving an account’ (p. 1). In many ways, these conditional grants only further entrench performative accountabilities, of being held to account and giving an account. School principals are willing to ‘stick to the rules’ and ‘tick the boxes’ in order to have their wellbeing program, or professional development program funded, or to acquire additional resources for the school, but the interviewees each noted the negative impacts on their time, excessive accountability requirements, and how this was accompanied by deficit mindsets about low-SES public school leaders.

Deficit mindsets and performative accountability

As is common in venture philanthropic mindsets regarding public schools (Saltman, 2010; Williamson, 2018), these grants arguably carry deficit paradigms regarding disadvantaged public schools and the work of principals in these schools. As part of the conditions of this grant, Ryan received a ‘coach’ from Schools Plus, as he explains:

He’s a retired principal but I think he must do this kind of thing with five or six different groups. So he has set questions, he has a set PowerPoint and then he sends us everything by email and then the next time we meet him in three months’ time, he says, ‘Did everyone have a chance to do that?’ But of course it’s three months later, so whatever I might have done, I’ve forgotten about, and whatever I forgot to do, I pretend I’ve done and everyone just keeps going.

I understand that… there has to be an accountability side of things, so that’s what I see it as. This is accountability and I’ll stick to the rules and do what I have to do and hope that they give me more money next year.

(Ryan, primary school principal, 17th August 2023)

Philanthropic grants are frequently paired with conditions and obligations, exacerbating performative accountability requirements. Indeed, as Ball and Junemann (2012) explain, the more ‘hands on approach’ to the way that donations are used and managed is indicative of ‘new’ philanthropy (p. 49). The way in which new philanthropy functions entrenches significant power gaps and power differentials into the system, where time-poor principals are ‘ticking the boxes’ and adhering to performative accountability cultures (Holloway and Brass, 2017; McKay, 2018; Mockler and Stacey, 2021), in a bid for additional funding. These systems of performative accountability can ‘become toxic in situations where the balance is lost’, and are based upon ‘coercive relations’ (Lingard et al., 2017, p. 3), a situation where budget-deficits compel time-poor principals to compete in philanthropic lotteries, and where registered charities become—not only the adjudicators of limited funds—but the evaluators of whom is deserving of the limited funds (see Ozga, 2009).

Arguably, the coaches that Schools Plus provides should be an optional aspect of winning a grant but instead functions as a performative requirement for a school principal, one that articulates a deficit mindset regarding their professionalism and work. Extra funding is provided, but only when school principals compete and apply, and contingent upon adhering to rules and requirements, such as compulsory ‘coaching’ sessions. Schools Plus frames the coaching as a way to ‘provide guidance and support’ and ‘the resources they [schools and project leadership teams] need’ (Schools Plus, 2023b). However, we might suggest that principals are providing feedback according to the performative accountability frames they are positioned in.

For example, for Ryan, when he talks about the benefits of the coaching sessions at a Schools Plus event, he is simply being ‘polite’, because that is the expectation. He expands on the ‘measuring of impact’:

So, for example, I go to these sessions in the afternoons with Schools Plus, and I have no idea how they’re measuring impact [of the grant]… Why are we having a massive impact on students’ writing? I don’t think anyone knows or cares. How are we measuring that? I think we could give them any measures that we pulled out of our hat and they would accept them.

(Ryan, primary school principal, 17th August 2023)

It is possible that for organisations such as these, the ‘performing’ of impact is more important than thoughtful or authentic measures of impact; and rather, it is based upon ‘what looks good’ for Schools Plus (Interview), in terms of what they are able to leverage, market and advertise in their Impact Reports. Within the logics of venture philanthropy, the organisation must be able to ‘sell’ their own purpose and impact.

Principal Timothy expands on the accountability component of the grant. Timothy received a $20,000 grant from Schools Plus and believed there were too ‘many strings attached’:

But [the grant] was so intricately managed … and we’ve never gone back to it because there were just so many strings attached. And I totally understand that funds need to be accounted for, but the way in which they wanted us to account –I had to have regular meetings with the manager ... I was sending them all the financials from our balance sheet report. It was all completely transparent. But they wanted to pick into every detail, so it took so much time that we’ve never applied for that grant again.

(Timothy, secondary school principal, October 27th 2023)

From a systemic viewpoint, the experiences of the interviewees highlights fairly blatant differences and discrepancies, between the funding that public schools must ‘fight’ and ‘compete’ for, compared to the minimal strings-attached capital funding that is received by private schools, such as the large balloon payments that elite schools received during the pandemic (JobKeeper) (see Conifer, 2022). It suggests that the current model of funding is inefficient for public schools, directly disadvantaging public schools and their leadership.

There is also the extractive issue of time for the principals, and Timothy points to the labour required for this relatively nominal amount:

We would never apply for this grant again. We were very grateful to have got the money and we spent it in the targeted areas around student engagement that we were meant to do. But it wouldn’t be worth our while—if it was 100 grand or a really substantial amount of money, but to go through all that pain for 20 grand wasn’t worth it. So to be honest, that put a bit of a sour taste in my mouth. (Timothy, secondary school principal, October 27th 2023)

The Schools Plus organisation are perhaps not cognisant of how time-poor school principals and teachers are (Creagh et al., 2023; Fitzgerald et al., 2018), but so too, organisations such as these often carry little personal experience of working in schools, and the day-to-day experiences of school leaders (Thomson, 2000). Deficit mindsets are carried into the grants in that imposed grant conditions create excessive performative accountability measures, without sufficient return, and in the context of systemic under-funding. The deficit mindset and emphasis on ‘selling’ themselves was indicated in an earlier interview with Schools Plus:

But schools are not great at telling their stories and showing demonstrable evidence. So the evaluation piece, I think the data is there, they’re just… not great at telling the story.

(Interview with high-level representative from Schools Plus, 9th July 2020)

In this, public schools are obligated, compelled or encouraged to ‘sell’ and package their story of disadvantage (Hogan et al., 2023) in order to receive funding for their schools, imposing a different skill-set and professionalism for school principals.

Conclusion

This paper has endeavoured to investigate public school principals’ experiences with philanthropic competitive funding and move away from reductive conceptualisations of philanthropy. We examined results from a survey in addition to in-depth interviews with public school principals from Queensland, Victoria, New South Wales and the Northern Territory. The leaders represented a range of school SES contexts, in addition to metropolitan, regional and remote public schools. Inadequate and insufficient funding of public schools causes principals to look to a wide variation of sources to generate greater revenue, to pay for projects such as school infrastructure, wellbeing programs and professional development.

Public school principals expressed dilemmas and ambivalences regarding philanthropy, regarding it as a ‘double-edged sword’. It is unsurprising, and perhaps to be expected, that principals reported some positive aspects of philanthropic funding, since it brought in ‘much needed’ funding and resources into the school; especially when interviewees reported their schools were under-funded and under-resourced. Many school principals said that philanthropic funding was important, or very important, because it enabled options and experiences for their students that they didn’t have before and provided necessary resources in the school. But on the other hand, many school principals regarded the pursuit of philanthropic funds as a distraction from their more important jobs and described the applications in overly negative terms, using words such as ‘battle’, ‘gruelling’ or ‘exhausting’. The pursuit of philanthropic funds reshaped principals’ attention, time and expertise, and encroached into their professional and personal lives in significant, consistent ways.

However, there was very little ambivalence in the data as to whether philanthropy represented a long-term or satisfactory solution for under-funding; the vast majority, as we reported in this paper, gave this question a resounding ‘no’. We would argue that it is necessary and essential to ensure that philanthropy in public schools is regulated (e.g. conditionality of the grants, imposed requirements onto principals or schools, and the application process), and public schools are strongly funded from the government.

Certainly, some of this ambivalence also related to principals wanting the freedom or opportunity to apply for philanthropic funding to build relationships with local businesses, or fund passion projects, or particular niche programs that might not be funded by the government. However, in the context of systemic under-funding, when school principals are experiencing significant time pressures and accountability measures, philanthropy is not being utilised for this gap; this study found it is being used to fill important funding deficits, such as teachers and staffing, or operational infrastructure, and overwhelmingly not being used for niche programs or passion projects.

We argue that philanthropic funders carry deficit mindsets regarding public schools, with this centring upon school leaders in low-SES public schools. The philanthropic grants are conditional (as contrasted to unconditional grants) and the ‘winners’ must undertake ‘coaching’ sessions, with principals attending ‘interview style’ sessions, described as formulaic and standardised, reinforcing the ideology that under-funding or resource inequities can be overcome through corrective coaching for school principals. Yet, this system of competitive, philanthropic grants in under-funded schools only perpetuates time-pressures as principals competitively apply for relatively nominal amounts of funding. The process reifies significant power imbalances, as the philanthropic granters assume the role of funding arbiter and judge; and the public schools take on the position of aspirant contender and hopeful contestant.

Herein, we found that philanthropic funding replicated market logics and performative accountability measures. From their experiences with the government-subsidised charity Schools Plus, the interviewed school principals felt there were ‘too many strings attached’, or the organisation ‘wanted too much’, for nominal amounts of funding. However, this is only a small number of principals and it would be useful for further research to investigate their experiences of philanthropic funders and charities, such as Schools Plus.

In summary, principals’ drive to generate philanthropic funding and engage in time-demanding applications is anchored within systemic under-funding in public schools. Interviewed and surveyed principals believed that philanthropy provided many resources that were necessary in their schools, but they strongly agreed that it fails to address systemic under-funding, and rather it is a short-term fix. So too, we would argue that it exacerbates broader, systemic issues, not only of under-funding, but adequate resourcing in public schools, and workload and work intensification for school leaders (Creagh et al., 2023). It demands a fundamental shifting of the role of school principal to grant chaser and revenue raiser, detracting from their core duties. These findings offer empirical support for the work of Hogan et al. (2023) who argue that Schools Plus ‘actively cultivates entrepreneurial cultures and practices for schools’, positioning disadvantaged schools as ‘“sellers” who must learn to market themselves in order to demonstrate their worthiness, need and capacity to donors’ (pp. 773, 774).

Whilst we acknowledge this study is limited in scope, this paper seeks to open up broader debate and questions regarding school principals’ experiences with philanthropic organisations, as divorced from their more obligatory and performative reports. Importantly, the only insight that has been offered into school principals experiences with these organisations is the one provided by Schools Plus in their marketing/impact reports (Schools Plus, 2023a). These are clearly limited and conflicted in presenting school principals’ authentic day-to-day experiences regarding philanthropic grants, and it is necessary for further research to investigate the systemic impacts of government-subsidised ‘philanthropy’ on public schools.

Data availability

The dataset is not available in a public repository at time of writing but it will be considered at a later date once concluded.

Notes

Although, important to note that McGoey consistently argues this is a very low level of criticism (see McGoey 2018).

Annual government funding in the last financial year, according to current financial data available from Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC) at time of writing. All dollars are Australian Dollars (AUD).

The Australian Capital Territory (ACT) is the only jurisdiction in Australia that fully funds its public schools according to the Schooling Resource Standard (SRS); it is also the smallest jurisdiction with the lowest number of schools (both public/private) at time of writing.

References

ACARA. (2019). Data Standards Manual: Student Background Characteristics. For use by Schools and School Systems, Test Administration Authorities, Assessment Contractors. edition.

ACARA. (2024). Technical and statistical information. ACARA (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority). Retrieved March 9 from https://www.myschool.edu.au/technical-and-statistical-information

ACNC. (2023). Teach For Australia Annual Information Statement 2022 [this is the most up-to-date/current Annual Information Statement available at time of writing]. Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission. Retrieved 26 April from https://www.acnc.gov.au/charity/charities/ade42739-38af-e811-a961-000d3ad24182/documents/9ea7027d-f2fd-ed11-8f6d-00224893bd39

ACNC. (2024a). Australian School Plus Ltd Annual Information Statement 2023. Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission. Retrieved March 8 from https://www.acnc.gov.au/charity/charities/db1d7bf3-39af-e811-a95e-000d3ad24c60/documents/7239607c-d4b4-ee11-a567-002248935564

ACNC. (2024b). Berry street Victoria incorporated annual information statement 2023. Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission. Retrieved April 26 from https://www.acnc.gov.au/charity/charities/0d229851-39af-e811-a962-000d3ad24a0d/documents/016db8ce-5f83-ee11-8179-002248122521

ACNC. (2024c). Search for a charity. Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission. Retrieved February 8 from https://www.acnc.gov.au/charity/charities

AEU. (2024). Ending the capital funding divide in Australia’s schools. Australian Education Union. Retrieved 23 February from https://www.aeufederal.org.au/news-media/news/2024/ending-capital-funding-divide-australias-schools

Au, W., & Lubienski, C. (2017). The role of the gates foundation and the philanthropic sector in shaping the emerging education market: lessons from the US on privatization of schools and education governance. In A. Verger, C. Lubienski, & G. Steiner-Khamsi (Eds.), World yearbook of education 2016: The global education industry (pp. 27–43). Routledge.

Australian Government. (2011). Review of funding for schooling: Final report December 2011. Canberra City, ACT: Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations

Australian Government. (2018). National school resourcing board: Review of the socio-economic status score methodology. Final Report June 2018. Commonwealth of Australia. https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/national_school_resourcing_board_ses_review_final_report.pdf

Australian Government. (2024). How schools are funded. Australian Government Department of Education. Retrieved January 5 from https://www.education.gov.au/schooling/how-schools-are-funded

Ball, S. J., & Junemann, C. (2012). Networks, new governance and education. The Policy Press.

Ball, S. J., Junemann, C., & Santori, D. (2017). Edu.net: Globalisation and education policy mobility. Routledge.

Beazley, J., & Cassidy, C. (2023). Private school funding increased twice as much as public schools’ in decade after Gonski, data shows. The Guardian. Retrieved 17 July from https://www.theguardian.com/education/2023/jul/17/gonski-review-government-funding-private-public-schools

Beazley, J. (2023). Australian public school funding falls behind private schools as states fail to meet targets. The Guardian. Retrieved July 24 from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/jul/24/australian-public-school-funding-falls-behind-as-states-fail-to-meet-targets

Chan, S. S. W., Thomas, M. A. M., & Mockler, N. (2022). Amplifying organisational discourses to the public: Media narratives of teach for Australia, 2008–2020. British Educational Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3840

Conifer, D. (2022). Hundreds of millions of dollars in JobKeeper went to a group of private schools that grew their surpluses to almost $1 billion. ABC News. Retrieved May 20 from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-05-20/millions-in-jobkeeper-went-to-private-schools-that-grew-surplus/101075098

Creagh, S., Thompson, G., Mockler, N., Stacey, M., & Hogan, A. (2023). Workload, work intensification and time poverty for teachers and school leaders: A systematic research synthesis. Educational Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2023.2196607

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Pearson.

Fitzgerald, S., McGrath-Champ, S., Stacey, M., Wilson, R., & Gavin, M. (2018). Intensification of teachers’ work under devolution: A ‘tsunami’ of paperwork. Journal of Industrial Relations, 61(5), 613–636. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185618801396

Fontdevila, C., Verger, A., & Avelar, M. (2021). The business of policy: A review of the corporate sector’s emerging strategies in the promotion of education reform. Critical Studies in Education, 62(2), 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2019.1573749

Gerrard, J., Savage, G. C., & O’Connor, K. (2017). Searching for the public: School funding and shifting meanings of ‘the public’ in Australian education. Journal of Education Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2016.1274787

Gonski, D. (2016). Donations are not a substitute for government funding of schools. UNSW Sydney Newsroom. Retrieved 25 October from https://www.unsw.edu.au/newsroom/news/2016/10/donations-are-not-a-substitute-for-government-funding-of-schools

Hogan, A., & Williamson, A. (2022). Mapping categories of philanthropy in Australian public schooling. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2022.2071841

Hogan, A., Gerrard, J., & Di Gregorio, E. (2023). Philanthropy, marketing disadvantage and the enterprising public school. The Australian Educational Researcher, 50(3), 763–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00524-5

Holloway, J., & Brass, J. (2017). Making accountable teachers: The terrors and pleasures of performativity. Journal of Education Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1372636

Jobér, A. (2023). Private actors in policy processes entrepreneurs, edupreneurs and policyneurs. Journal of Education Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2023.2166128

Kenway, J., Bigum, C., & Fitzclarence, L. (1993). Marketing education in the postmodern age. Journal of Education Policy, 8(2), 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093930080201

Kolleck, N. (2019). The power of third sector organizations in public education. Journal of Educational Administration. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-08-2018-0142

LA Times. (2023). Gates Foundation failures show philanthropists shouldn’t be setting America’s public school agenda. LA Times. Retrieved 14th November from https://www.latimes.com/opinion/editorials/la-ed-gates-education-20160601-snap-story.html

Le Feuvre, L., Hogan, A., Thompson, G., & Mockler, N. (2023). Marketing Australian public schools: The double bind of the public school principal. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 43(2), 599–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2021.1953440

Lingard, B., Sellar, S., & Lewis, S. (2017). Accountabilities in schools and school systems. Oxford University Press.

Lubienski, C. (2016). Sector distinctions and the privatization of public education policymaking. Theory and Research in Education, 14(3), 192–212.

McGoey, L. (2015). No such thing as a free gift: The gates foundation and the price of philanthropy. Verso Books.

McGoey, L., Thiel, D., & West, R. (2018). Philanthrocapitalism and crimes of the powerful. Politix. https://doi.org/10.3917/pox.121.0029

McKay, A. (2018). The accountability generation: Exploring an emerging leadership paradigm for beginning principals. Discourse, 39(4), 509.

McKay, A., Bright, D., Kim, M., Longmuir, F., & Magyar, B. (2022). ‘I cannot sustain the workload and the emotional toll’: Reasons behind Australian teachers’ intentions to leave the profession. Australian Journal of Education, 66(2), 196–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/00049441221086654

Mockler, N., & Stacey, M. (2021). Evidence of teaching practice in an age of accountability: When what can be counted isn’t all that counts. Oxford Review of Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1822794

OECD. (2016). Low-performing students: why they fall behind and how to help them succeed. OECD.

Ozga, J. (2009). Governing education through data in England: From regulation to self-evaluation. Journal of Education Policy, 24(2), 149–162.

Philanthropy Australia. (2023a). Philanthropy Australia welcomes the commencement of the productivity commission ‘double giving’ review. Philanthropy Australia website. Retrieved 11 February from https://www.philanthropy.org.au/news-and-stories/philanthropy-australia-welcomes-the-commencement-of-the-productivity-commission-double-giving-review/

Philanthropy Australia. (2023b). Schools plus gets $3m boost from Google. Philanthropy Australia website. Retrieved 23 June from https://www.philanthropy.org.au/news-and-stories/schools-plus-gets-3m-boost-from-google/?apcid=00639263d8921fccc69d4600&utm_campaign=3-78-23-june-2023-member&utm_content=3-78-23-june-2023-member&utm_medium=email&utm_source=ortto

Productivity Commission. (2023). Productivity commission inquiry: Philanthropy. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/current/philanthropy#draft

Preston, B. (2023). Report on a national symposium funding, equity and achievement in australian schools. https://www.barbaraprestonresearch.com.au/social_justice.html

Reckhow, S. (2013). Follow the money: How foundation dollars change public school politics. Oxford University Press.

Reich, R. (2018). Just giving: Why philanthropy is failing democracy and how it can do better. Princeton University Press.

Reikosky, N. (2023). Pipeline philanthropy: understanding philanthropic corporate action in education during the COVID-19 era and beyond. Educational Policy. https://doi.org/10.1177/08959048231163802

Rorris, A. (2021). Investing in schools—Funding the future. Australian Education Union Federal. Retrieved August 5 from https://www.aeufederal.org.au/application/files/5716/2278/1619/AEU197_Investing_in_Schools_Report_v5_REV.pdf

Rorris, A. (2023). How school funding fails public schools: How to change for the better. https://www.aeufederal.org.au/application/files/3817/0018/3742/Rorris_FundingFailsPublicSchools.pdf

Rowe, E. (2022a). The assemblage of inanimate objects in educational research: mapping venture philanthropy, policy networks and evidence brokers. International Journal of Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2022.102005

Rowe, E. (2022b). Philanthrocapitalism and the state: Mapping the rise of venture philanthropy in public education in Australia. ECNU Review of Education, 6(4), 518–540. https://doi.org/10.1177/20965311221128840

Rowe, E. (2022c). Policy networks and venture philanthropy: a network ethnography of ‘Teach for Australia.’ Journal of Education Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2022.2158373

Rowe, E. (2023). Venture philanthropy in public schools in Australia: Tracing policy mobility and policy networks. Journal of Education Policy, 38(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2021.1973569

Rowe, E., & Langman, S. (2024). Competitive grants in autonomous public schools: how school principals are labouring for public school funding. Australian Educational Researcher, In Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-024-00746-9

Rowe, E., Langman, S., & Lubienski, C. (2024). Privatising public schools via product pipelines: Teach for Australia, policy networks and profit. Journal of Education Policy, 39(3), 384–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2023.2266431

Saltman, K. J. (2010). The gift of education: Public education and venture philanthropy. Palgrave Macmillan.

Savage, G. C. (2016). Think tanks, education and elite policy actors. The Australian Educational Researcher, 43(1), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-015-0185-0

Schools Plus. (2023b). Schools plus website. Retrieved November 5th from https://www.schoolsplus.org.au/

Schools Plus. (2023a). Schools plus impact report 2022: Together, we can help close the education gap. https://www.schoolsplus.org.au/about-us/reports/

Thomson, P. (2000). Like schools’, educational ‘disadvantage’ and ‘thisness. The Australian Educational Researcher, 27(3), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03219737

Tompkins-Stange, M. (2016). Policy patrons: Philanthropy, education reform and the politics of influence. Harvard Education Press.

Traill, M. (2016). Jumping Ship: From the world of corporate Australia to the heart of social investment. Hardie Grant Books.

Wark, T. (2024). AAP FactCheck: Labor’s school funding pledge may trip on ‘loophole’. Retrieved February 16 from https://www.aap.com.au/factcheck/labors-school-funding-pledge-may-trip-on-loophole/

Williamson, B. (2018). Silicon startup schools: Technocracy, algorithmic imaginaries and venture philanthropy in corporate education reform. Critical Studies in Education, 59(2), 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1186710

Windle, J. (2009). The limits of school choice: Some implications for accountability of selective practices and positional competition in Australian education. Critical Studies in Education, 50(3), 231–246.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the public school principals who gave us their time to complete the survey and provide an interview. This study was funded by the Australian Research Council [Discovery Early Career Researcher Award]. Human Ethics was provided by Deakin University. Thank you to Dr. Mark Rahimi from Deakin University for his assistance in developing the survey used for this project. We received insightful reviews on the first drafts of this paper and we are grateful to the reviewers for their constructive feedback.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The study is funded by the Australian Research Council DECRA (DE210100513) from 2021 to 2024.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both named authors contributed to the work. The paper is based on Emma Rowe’s funded study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

The ethical approval has been received from Deakin University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (DUHREC). Project number is: HAE-21-132. The study adheres to the ethics principles.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rowe, E., Di Gregorio, E. Grant chaser and revenue raiser: public school principals and the limitations of philanthropic funding. Aust. Educ. Res. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-024-00750-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-024-00750-z