Abstract

This paper examines competitive grants for public schools, as a form of additional funding from the government. We draw on interviews with principals from different states in Australia to examine systemic impacts of competitive grants for public schools, exploring this in relation to school autonomy. Public school principals are labouring to generate additional school funding via competitive applications from the traditional state government, to supplement their core or regular government funding. The competitive applications are to fund what many would consider rudimentary or fundamental resources, such as school infrastructure and student wellbeing programs. For the interviewed principals, the drive to generate more funding was anchored within significant government funding shortfalls in public schools. The majority of interviewees did not find the funding model to be ‘needs-based’ or responsive. Autonomous public schools presented many paradoxes and contradictions, particularly in under-funded contexts; whilst on one hand, principals are tasked with managing their budgets, the majority experienced the environment as highly inflexible and often punitive, laden with bureaucratic red tape. The majority of interviewees expressed notions of responsibilisation for generating additional funds. In this context, we found that competitive funding applications increase school principal work intensification, with principals spending excessive time labouring to generate additional funding via competitive grant applications, in order to fund essential school projects. The labour involved in completing time-demanding funding applications supplants their traditional responsibilities and is critically reshaping their role as a school principal, to one of ‘grant applier’ and fundraiser, reinforcing the retreat of the traditional state.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

And the frustrating thing is we all know schools need more support financially, that’s just a no-brainer, but it feels very frustrating that to run a school successfully you feel like part of your work is generating more funds. [Susan, public school principal, secondary school: New South Wales. Advantaged student cohort.]

This paper examines competitive grants for public schools, as a form of additional funding from the government. We draw on interviews with principals from different states in Australia to examine systemic impacts of competitive grants for public schools, exploring this in relation to school autonomy (Fitzgerald et al., 2018; Gavin & Stacey, 2023; Keddie, 2016; Niesche et al., 2023). The competitive applications are to fund what many would consider rudimentary or fundamental resources, such as school infrastructure and student wellbeing programs. For the interviewed principals, the drive to generate more funding was anchored within significant government funding shortfalls in public schools.

There is scope to expand upon empirical research regarding competitive funding in public schools as a supplementary source of revenue raising from the state government. Important empirical contributions have examined similar and interconnecting areas of research; for instance, public schools generating additional funding through parent contributions and fundraising (Rowe & Perry 2020a, b, 2022; Thompson et al., 2019), commercial and corporate partnerships (Enright et al., 2020), or philanthropic competitive applications, through organisations such as Schools Plus (Rowe & Di Gregorio, In Press; Hogan et al., 2023). Internationally, research indicates there is increasing emphasis on generating private funds for public schools (Fallon & Poole, 2014; Poole et al., 2020; Winton, 2018a, 2018b; Yoon et al., 2019).

In similarity with the aims of this study, Niesche (2010) examined the experiences of two school principals from private schools in rural Queensland, serving mainly Indigenous students, and their labour in generating funding through competitive grants. He writes that ‘an increasing part of the principal’s job, under moves towards self-governing schools, is a reliance of grants …to obtain funding’, a process which emphasises entrepreneurial leadership, reducing time spent on ‘important matters of curriculum and pedagogy that are critical in educational leadership’ (p. 249). In similarity, we pay attention to public school principals engaging in competitive funding applications via the traditional state, in order to supplement their funding, and how this impacts school principal workload (Creagh et al., 2023; Stacey et al., 2023), as principals are compelled to be revenue creators, in autonomous public schools (Blackmore, 2005; Gobby, 2013; Gobby et al., 2018; Mockler et al., 2023; Niesche, 2010).

The paper is structured as follows; as school principals primarily locate their competitive applications within a need for more funding, the following section discusses under-funded public schools, followed by the impact of an inequitable funding system. This is succeeded by a discussion of autonomous public schools. We then turn to explain the methodology for how data was generated, followed by analysing the interviews with public school principals.

Public or ‘government’ schools and how they are funded

Significant inequities in Australia’s approach to school funding encourages competition, marketisation and consumer-choice, as parents are nudged to be active school choosers, for all schools to compete, and with so-called ‘needs-based’ funding following the student (Bonnor & Shepherd, 2016; Connors & McMorrow, 2015; Preston, 2023; Rorris, 2023; Stewart & Russo, 2001; Windle & Stratton, 2013). Economist Rorris (2021) writes that ‘investment in Australian schools has favoured private schools to an astonishing degree’ (p. 5).

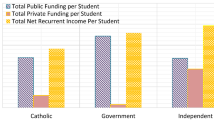

In Australia, ‘public’, or state/government schools, receive the majority of their recurrent funding from the state or territory government in which it is located, whereas private schools (‘non-government’), consisting of Independent and Catholic schools, receive the majority of their recurrent funding from the federal government (Australian Government, 2024b). Funding consists of ‘recurrent’ and ‘capital’ funding, in addition to private sources, with the ‘recurrent’ funding calculated through a measurement referred to as the ‘Schooling Resource Standard’ (SRS) (Australian Government, 2011). The SRS is a theoretically needs-based measure and estimate of ‘how much public funding a school needs to meet its students’ educational needs’ (ACARA, 2021, p. 115), consisting of a base amount for every student and up to six needs-based loadings to provide extra funding, relating to socio-educational disadvantage, location and English language proficiency (ACARA, 2021; Australian Government, 2024a).Footnote 1

Public schools are currently not funded according to their Schooling Resource Standard (SRS) or measure of ‘need’, in the majority of states and territories (with the exception of the Australian Capital Territory) (Beazley, 2023; Beazley & Cassidy, 2023; News, 2023; Wark, 2024). Recent analyses of Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) data indicates funding targets have been exceeded for private schools:

ACARA data shows that 98% of private schools are funded above the Schooling Resource Standard (SRS) … and more than 98% of public schools are funded below it. (Beazley & Cassidy, 2023, our emphasis)

Rorris (2023) points to how this has been achieved via ‘deceptive accounting tricks’, pointing to the bilaterial agreements negotiated between the federal government and the states, following the 2013 federal election of a more conservative political party. These funding agreements were detrimental towards public schools; as the agreements allowed state/territories to include ‘additional expenditure items’ (up to 4%) within their Schooling Resource Standard, which artificially bolsters funding to public schools, including ‘capital depreciation, school transport, regulatory authorities’ (Rorris, 2023, p. 11). The same is not applied to private schools.

The shortfalls are numerous and significant within the funding model, as private schools benefit from greater levels of capital funding (Ting et al., 2019), with Windle (2009) describing this as ‘an embarrassment of riches’ (p. 233). The average expenditure of capital investment in private schools is higher, in comparison to public schools and ‘over the decade from 2012 to 2021 capital investment in public schools averaged $1110 per student per year, whilst in private schools the average was $2401 per student per year—more than double’ (AEU, 2024, p. 5). This is described as the ‘capital investment gap’, with particular states demonstrating a wider gap over 10 years (New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland), and public schools receiving significantly less in capital funding compared to private schools (Rorris, 2021). One of the reasons for this disparity was due to private schools retaining access to dual sources of capital funding (federal and the states), whereas public schools were only able to access a singular source of funding from the state (for capital works) (AEU, 2024; Ting et al., 2019). However in 2023, the federal government introduced the first capital works funding program for public schools, referred to as the School Upgrade Fund (Australian Government, 2024c). This is a single year, one-off fund at time of writing (AEU, 2024).

This disparity has been building for considerable time, with Stewart and Russo (2001) writing over twenty years ago that capital funding was much higher for private schools compared to the public sector, and even when taking into account the drift of students to private schools, the ‘provision of funds to the non-government sector has been increasingly disproportionate’ (Stewart & Russo, 2001, pp. 33, 34).

The impact of inequitable funding models

Inequitable funding models are linked to school segregation, as better-resourced families tend to choose better-resourced schools. Australia demonstrates high levels of between-school segregation, as more advantaged families are more likely to enrol in private schools, particularly the high-feeFootnote 2 Independent school sector (Bonnor & Shepherd, 2016; Connors & McMorrow, 2015; Perry et al., 2024). Perry et al. (2016) write that ‘the average income and SES of students in private schools is higher than in public schools’ (p. 176). Chesters (2018) found that ‘students with highly educated parents were more likely than other students to attend independent schools’ (p. 139). Disadvantage is ‘increasingly concentrated’ in public schools (Bonnor & Shepherd, 2016, p. 8), and whilst there are exceptions, particularly with select-entry public schools educating high proportions of advantaged students (Rowe & Perry, 2022), and conversely remote private schools educating high proportions of disadvantaged students, from a nation-wide perspective, students who are categorised as more disadvantaged, due to parent(s) experiencing homelessness, poverty or unemployment, are more likely to be educated in the public school sector. Lamb et al. (2015) pointed to nearly 80% of students from disadvantaged backgrounds enrolled in public schools. The majority of Indigenous students (82.4% nation-wide) attend public schools (ABS, 2023). The majority of students experiencing a disability are enrolled in public schools (approximately 75%) (Hunter, 2019; Smith et al., 2023).

Inequitable funding models are linked to inequitable distribution of quality school resourcing, including experienced teachers and specialised teachers; professional development for teachers; quality textbooks and learning materials; and school facilities and infrastructure, such as science laboratories, libraries, sporting facilities; and improved teacher to student ratios (Chiu & Khoo, 2005; Murillo & Roman, 2011; OECD, 2013; Powers, 2004; Watson & Ryan, 2010). There is ‘growing inequality … between students who have access to educational opportunities and outcomes’ (Mills et al., 2022, p. 345). Lower-SES public schools and their communities tend to be cast as ‘in deficit’, particularly in regard to aspirations (Zipin et al., 2015, p. 229).

Whilst spending money on education does not necessarily equate to higher learning outcomes, per-pupil spending is positively associated with improved learning outcomes (Baker, 2016; Chiu & Khoo, 2005) and provides a necessary underpinning for access to high-quality learning resources and opportunities. Chiu and Khoo (2005) write that students score higher on standardised tests, in mathematics, reading and science when they retain access to higher level of resourcing. An OECD (2013) report writes that ‘adequate resources are crucial for providing students with high-quality opportunities to learn’ (p. 40) and ‘high performing systems tend to allocate resources more equitably between socio-economically advantaged and disadvantaged schools’ (OECD, 2013, p. 103). High-performing systems restrict the resource gap between advantaged and disadvantaged schools (OECD, 2013).

In the following section, we contextualise school principal’s competitive applications for funding, within autonomous public schools in the state/territories of Victoria, Queensland, and New South Wales.Footnote 3

Autonomous public schools

Alongside policies that have encouraged school choice and marketisation, the devolution of public schools and autonomy reform has been a central policy feature in Australia since the 1980s (Blackmore et al., 2023; Gavin & Stacey, 2023; Gobby et al., 2018; Niesche, 2010), reflecting international trends to decentralise schools (OECD, 2020). Whilst these reforms have differed according to the states in which they have been enacted (MacDonald et al., 2023), the reforms have increasingly shifted traditional responsibilities of the welfare state, encouraging the principal to be ‘more like a CEO’ (Gobby, 2013), to be managerial, entrepreneurial and performative (Blackmore, 2005; Keddie et al., 2018; Mockler et al., 2023; Niesche et al., 2023).

The states/territories in which the interviewees are located represent public school contexts that emphasise autonomy, albeit with differences. Arguably, Victorian schools reflect the most decentralised system,Footnote 4 with ‘devolved decision-making and financial management system… shared between the school council and the principal’ (DET VIC, 2024).Footnote 5 The 2011 Gonski Review wrote that schools in Victoria maintain a ‘high degree of autonomy’, pointing to management of funds and staff appointments (Australian Government, 2011, p. 43). Further to this, and in relation to this study, there are a number of competitive grants available through the Victorian Department of Education (e.g. the School Shade Sails Fund, Inclusive Schools Fund, Minor Capital Works Fund) (DET VIC, 2023; VSBA, 2023a, 2023b).

New South Wales has historically been regarded as a centralised system (Australian Government, 2011; Gavin & Stacey, 2023), although more recent reforms have sought to move it towards decentralisation (e.g. Local Schools, Local Decisions). Queensland is described as a centralised system (Australian Government, 2011), although it has adopted different reforms over the years (e.g. Independent Public Schools) (Keddie et al., 2018). According to the Department of Education, public schools in Queensland ‘have significant autonomy in the management of their resources’ and the policy vision is for ‘flexible, needs-based and outcome-focused school resourcing’ (Department of Education QLD, 2022, p. 5, emboldened in original).

Overall, school autonomy reforms in Australia have largely worked towards greater ‘flexibility’ for school principals in resourcing their schools, and managing their financial budget (Blackmore et al., 2023). Withstanding state differences, there has been a shared emphasis on the devolution of budgets onto schools, individualising and responsibilising ‘principal discretion over expenditure’ (Blackmore et al., 2023, p. 548), and we would argue, the growing expectation to generate revenue.

In this paper, we are concerned with the devolution of school budgets onto school principals, and how this has intensified workload and increased bureaucratic red tape, in the context of under-funding (Blackmore et al., 2023; Fitzgerald et al., 2018; Gavin & Stacey, 2023; Niesche et al., 2023). Scholars have argued that decentralised and autonomous public schools have resulted in increased workload for teachers (Fitzgerald et al., 2018; Stacey et al., 2023). In their study of devolution reforms in New South Wales, Fitzgerald et al. (2018) write that the reforms led to intensified workload for teachers, ‘especially in piles of paperwork’ and autonomy ‘could almost be defined as synonymous with increases in workload’ (Fitzgerald et al., 2018, p. 627).

In their study of autonomous schools in New South Wales, Gavin and Stacey (2023) write that autonomous reforms, whilst aiming to reduce red tape, resulted in the contrary. Despite some degree of ambivalences amongst the principals and teachers, there was an overwhelming consensus that the reforms did not reduce red tape. Principals disagreed that autonomous reforms simplified administrative processes (p. 514), and principals found the imposed financial management as ‘cumbersome, time-consuming and complicated’ (p. 515). Principals ‘reported difficulty in fulfilling their role as educational leader due to the large proportion of time spent on administration’ (p. 515). Furthermore, interview recipients reported ‘more pressure on schools and more responsibility and more blame’ and a ‘lot more red tape’, reducing time spent on teaching and learning (Gavin & Stacey, 2023, p. 515). Holloway and Keddie (2020) discuss how autonomous schooling environments only ‘notionally empower’ school principals, with this empowerment constricted and constrained by performativity measures (p. 788).

The following section discusses methodology and theoretical framing before analysing the interviews.

Methodology

This paper draws on in-depth interviews carried out with eighteen public school principals from July to November 2023, as part of a longer-term study exploring private actors in public education (see, Rowe & Di Gregorio, In Press). The following analysis focuses upon these in-depth interviews in alignment with a qualitative thematic analysis (Creswell & Creswell, 2023). The following table shows the interviewees according to the location of their school, divided by state/territory (see Table 1).

Schools have been calculated as disadvantaged or advantaged by drawing upon the School Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (hereby referred to as ICSEA) as a proxy for school socio-economic status (SES). ICSEA is a measurement specifically developed for the MySchool website by the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). Each school is allocated a unique ‘School ICSEA Value’, as based upon data collected at point of student enrolment (parent occupational status and educational attainment) and school-level data (school remoteness and proportion of Indigenous students) (ACARA, 2010). ICSEA values range from approximately 500 (representing extreme socio-educational disadvantage) to 1300 (representing extreme socio-educational advantage), and the index is scaled so that the national mean is 1000 (ACARA, 2018, 2019). The interviewees reflect a range of public schools, although the majority are leaders in schools serving disadvantaged cohorts of students (13 out of 18 interviewees).Footnote 6

Interviewees are from diverse school locations in terms of how it is classified on the ‘MySchool’ website within ACARA data (ACARA, 2024). Half of the interviewees are from schools located in ‘major cities’, whereas the remaining half consist of schools located in regional areas, remote and very remote (see Table 1). Therefore, the interviewed school principals’ experiences with generating additional funding as anchored within funding deficits are discussed across a range of public school settings, including those in lower- and higher-SES contexts in addition to remote and metropolitan demographics.

All of the interviewees are employed full-time in public schools as principals and hold substantial leadership experience, with the average interview participant reporting 11 years of employment within leadership roles in schools. Interviewee Adam reports the least experience (2 years) whereas Timothy reports the highest level of experience (22 years).

The data in this paper represents a small sample of interviews, considering there are 6712 government (public) schools in Australia at time of writing (ABS, 2023). Given the limitation of the sample size, it would be useful for further research to continue examining competitive funding applications and grant writing in public schools. We argue the paper contributes to an increasingly important and urgent area of research, that is, the growing emphasis placed onto principals in public schools to be revenue generators (see Rowe & Di Gregorio, In Press).

Finally, in analysing the data through a lens of qualitative thematic analysis, immediately following the interviews, the first and second author met to identify central themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006), and often work through the numerous ambivalences demonstrated throughout the interview. We identified similarities in the data in terms of the funding situation creating a system that provoked numerous ethical tensions, pressures and ambivalences for school principals (Holloway & Keddie, 2020; Le Feuvre et al., 2023; Mockler et al., 2023; Niesche, 2013).

Note that in the following analysis, interviewees often refer to ‘the Department’ as shorthand, which is a reference to their main funding body (the Department of Education).

School principal/grant applier

It’s about time. It’s having time and finding time. … And its changed. I didn’t come into this role being a grant applier. For me, it’s about the kids, the education, the passion of being here, it’s about being present. Not sitting in an office. I try every day to get to my classrooms and wave the kids off and on the bus and all of that kind of thing… I’ve already got enough paperwork to then have to compete for grants. I mean, even the Department, they put out grants. [Elizabeth, primary school principal, Victoria. Disadvantaged student cohort.]

Elizabeth speaks about how the role of principal now demands applying for competitive grants from the government, in order to supplement her budget, as a core part of her leadership work. Many of the interviewed principals expressed similar sentiments, such as Tom (secondary school, Queensland) who discussed how he feels he has become a ‘legal expert’ through reading all the legal jargon that is now required in grant applications. Many other interviewees referenced the need for ‘expert language’, ‘expertise’ or ‘outside expertise’ to bolster their applications and to stand out in a highly competitive field. Luke (secondary school, Queensland), for example, spoke about the increasing professionalism of grant writing, pointing to principals employing ‘professional grant writers’, paid as a proportion of successful grants and describing this as ‘big business’.

The deficit funding situation, combined with competitive funding grants, reposition and remodel the core work of a school principal. Interviewees expressed a sense of being pulled away from their perceived core duties as a school principal and towards these outward, competitive and marketised dynamics, so that their core job description now included generating additional revenue for their school, such as Susan who says that part of her work is ‘generating more funds’ (secondary school, New South Wales).

However, there were conflicts and expressed ambivalences towards this position, as well. On one hand, interviewed principals often felt ambivalent in regards to highly competitive applications for funding that demanded their time and expertise; but on the other, they felt it was necessary to maintain sufficient resources with the school, and ensure ‘school survival’ (Keddie, 2016; Mockler et al., 2023). It is a common theme amongst the interviewees:

My biggest issue at the moment is realistically … we are still underfunded. We’re not meeting the SRS targets as a state. And … there are … and there are things that are happening in schools that we are doing at the expense of other things. [So] being able to provide extra resources into the school, be it monetary or facilities, I do see that as part and parcel of my job, because at the end of the day it benefits the children and the teachers at the school. [Jason, primary school principal, Victoria. Advantaged school cohort.]

For many interviewees, the pressure to generate additional funding via competitive applications presented ideological, ethical and professional conflicts. There was a sense they were being drawn into jobs and roles they did not want to be pulled into, but in order to do the right thing ‘by the kids’, they engaged in funds-generating behaviour. For example, Elizabeth’s core work meant being present for the students, which was a common sentiment expressed by the interviewed principals. She also wanted to make time to meet with parents and staff. This point is reiterated by Creagh et al. (2023) in their literature review regarding workload, work intensification and time poverty, in that principals prioritised ‘being visible and present’ within their school, but the ramification of this was increased paperwork outside of school hours (p. 10). Niesche et al. (2023) write that in autonomous school settings, principals are ‘spending less time on leading instructional improvement in their schools’ and more time on administrative tasks (p. 1272).

Arguably, in a context of autonomous and decentralised schools, the interviewed principals were steered towards entrepreneurial and competitive grant writing as a method of revenue generating. Mockler et al. (2023) refers to this as the autonomy/choice/entrepreneurship nexus’ (p. 470), in that in an unregulated marketisation context, one that values school choice and school autonomy, there is an expectation that school principals will apply for competitive funding grants. Principal Mark speaks to this expectation, in relation to capital funding:

We had a retaining wall that needed a lot of work, and it was about $100,000 job, and [the Department] allocated $4,000 to it. And that’s common across all schools. So, you have to apply for these grants to try and get the big jobs done and top up the money. Because you don’t have enough money in your school budget. [Mark, primary school principal, Victoria. Advantaged student cohort.]

In this particular instance, Mark is engaging in competitive funding applications from the state government for what many would consider a fundamental capital project (a retaining wall) and competing with all other public schools across the state. Clearly this is anchored within a funding shortfall, and as common for all interviewees, a perceived deficit in capital funding to improve school infrastructure. It provoked school principals to take on additional labour to generate more capital funding for their school infrastructure, fundamentally reconfiguring their role as school leader to include the responsibility of chief grant applier.

The increase of ‘red tape’ and paperwork

In a similar way to previous studies of autonomous school settings and the increase of workload for both teachers and principals (Fitzgerald et al., 2018; Niesche et al., 2023), the interviewees report an intensification of paperwork; however, one of the major sources of paperwork in this study was the labour involved in generating additional revenue and funding for their schools through competitive grant applications. Tom expands on this, with a significant emphasis on time:

Yeah, it’s time… [applying for the grants is] a lot of time because yeah, you’ve just got to give up lots of time. And because they’re all different, they all generally have different requirements... They all have different layers of, I’m going to say, red tape in them. And usually the larger the amount you apply for, the more red tape. [Tom, secondary school principal, Queensland. Disadvantaged cohort.]

As indicated by Tom, from a disadvantaged school in Queensland, as the size of the grant increased, so did the administrative burden. This sentiment was shared by other interviewees as well, who spoke about how applications involved a great deal of bureaucratic ‘red tape’ (Gavin & Stacey, 2023). Tom continues to explain what some of the ‘red tape’ is caused by:

Some of this red tape relates to the differing requirements of the grant, which may demand soil reports, insurance advice, flood mitigation expertise, project management and legal expertise. [Tom, secondary school Queensland.]

Christopher, from a remote school in Queensland, concurred with the increased emphasis on ‘red tape’, saying that the applications involve ‘a shitload of bureaucratic red tape that you have to go through’ to acquire resources for his school (Christopher, combined school Queensland). However, Christopher was an outlier in some ways, showing higher levels of satisfaction in writing the grants, and was more at ease with this being part of his ‘core work’ as a school principal. Overall, only two interviewees, Christopher and Matthew from remote and highly disadvantaged schools in Queensland, shared this sentiment; however, Matthew acknowledged he did not write the grants himself (his Assistant Principal managed them). Furthermore, it is important to note that principals’ unease and dissatisfaction increased, the larger the competitive grant and bureaucratic requirements.

The contradictions of autonomous public schools

There were a number of contradictions of autonomous schooling contexts, particularly as they arose within an under-funded context: principals were tasked with reconfiguring their existing budgets, and were autonomous in this respect, but were also held to account in a number of different ways, and often with what they perceived as punishing outcomes.

The majority of interviewed school principals experienced funding as far from flexible or ‘needs-based’. For example, many principals expressed that they were ‘not allowed to save money from year to year’, especially if it was government-funding (rather than parent-generated or private funding); and whilst technically this is not true, as explained by participants, the overriding point was a fear of risky, punitive outcomes if they did, as Mark explains:

Yes, you can save [money]. You can leave money there. [But] If you do leave money in your accounts, you’re at risk that the Department will take it off you, or

they won’t provide you with … extra money because they’ll say, “You’ve already got $500,000 reserve.” [Mark, primary school principal, Victoria. Advantaged student cohort.]

Jason expanded on this,

[When applying for grants, you have to know] what the Department will be looking for. So particularly those facilities ones, like putting evidence in – including evidence to prove that you are expending all of your facilities budgets that the Department provides. There’s a big one around at the moment – and I don’t know if anyone’s spoken about this with you – but it’s about the amount of money that schools have sitting in their bank accounts. And that’s often where you’ll get push back from the Department. [Jason, primary school principal, Victoria. Advantaged school cohort.]

When asking him what he meant by the ‘push back’, Jason continued:

…. often the Department will push back facilities [competitive applications] to say, “You’ve got the money in the bank to be able to do that project.” Which, “Yes, fine. But here’s what” – being able to write back and say, “Yes, I do. But this is where the money is allocated for. It’s budgeted for. It’s for this purpose.” [Jason, primary school principal, Victoria. Advantaged school cohort.]

As Jason explains, and a common experience for the interviewed school principals, was the paradox of being both responsible for their budget, but equally constrained. When looking to make autonomous decisions that would benefit their school community, such as saving excess funds (often for larger projects, e.g. sporting infrastructure, or buildings), they perceived a disciplinary managerial reaction from the central authority. This suggested a perverse responsibilisation of school funding, coupled with a punitive regulatory and accountability environment.

The responsibilisation of school funding

The responsibilisation of school funding in autonomous public schools was perhaps best captured by Joe, a principal at a high-SES primary school in Victoria, who discussed at length his aging portable classrooms, which require fresh painting and carpets. What concerns him most, however, are the windows in the portable classrooms, which cannot be opened safely as they are ‘very old’ sash-windows that can suddenly fall closed. This presents a safety risk in the primary school, as they can act as a type of guillotine and could ‘take someone’s hand off’ [Joe]. The cost of fixing these windows doesn’t fit into his regular annual budget, and so each year, he resorts to applying for competitive grants from the Department, only to be unsuccessful each year (feedback is not provided on why).

In the course of his busy day as a principal, Joe resorts to posting numerous signs next to the windows and asking one of the parents at the school to nail the windows down. But he finds that occasionally, despite his best efforts, a casual teacher or someone unfamiliar with the school, manages to open one of the windows (presumably, to bring fresh air into the classroom). He laments this situation:

I mean you would think… the Department is very risk adverse. Right? And we have done everything we can to keep the windows safe and secure but just imagine if something bad happened. Then that would be my fault. It would be my responsibility. [Joe, primary school principal, Victoria. Advantaged school cohort.]

This points to the tensions of autonomous public schools: on one hand, Joe experiences systemic responsibilities to be compliant within what he later describes as excessive auditing practices, but on the other, the auditing practices do not facilitate a supportive funding environment in which his infrastructure requirements are met. Like many interviewed principals, they struggled to acquire adequate funding to meet compliance regulations as determined by the state. Furthermore, many discuss how this led to excessive amounts of pressure and workload, experiencing this as a type of personal responsibility—‘it would be my responsibility’—within a system that values managerialism and performativity (Ball, 2003; Niesche, 2013), encouraging school leaders to be like CEO’s (Gobby et al., 2018). Problems are constructed as ‘individual problems rather than systemic problems’ (Niesche et al., 2023, p. 1271).

For instance, Tom expressed what he saw as a consistent misalignment between the imposed performativities of the state, that is, how he is judged and assessed, with the funding he actually received:

The Department will introduce a strategy … like literacy or student wellbeing… and go, “Hey look, this is really important. Do these things.” But there’s no funds or resourcing to go with it. [Tom, secondary school principal, Queensland. Disadvantaged cohort.]

This is a common theme amongst the interviewed principals, as they perceived the central authority imposing certain demands, conditions and standards, but without the enabling supports for these conditions. The ‘lack of funds’ to support autonomy is expressed by participants, a theme also reiterated by Niesche et al. (2023). The contradictions of autonomous public schools in an under-funded context are positioned side-by-side in this instance. A school is hardly ‘free’ to exercise autonomy or be self-managing when starved of funds.

Conclusion

This paper examined competitive grants for public schools, as a form of additional funding from the government. Drawing on interviews with eighteen public school principals, it provided initial insights into the systemic implications of public school principals engaging in time- and labour-intensive practices of sourcing additional funding via competitive grant applications, in the context of autonomous and under-funded public schools.

Autonomous public schools construct paradoxical points of pressure (Gobby, 2013; Gobby et al., 2018; Holloway & Keddie, 2020; Keddie, 2016), particularly when they are under-funded. Principals are simultaneously free on one hand to generate additional funds and be entrepreneurial, while also beholden to generating additional funds, constraining and limiting their time and resources. This was a common sentiment and the majority of interviewed principals spoke to this perceived sense of responsibility to generate additional funds. This labour was clearly exacerbated by funding deficiencies and shortfalls, which related to multiple projects including school infrastructure and student wellbeing programs.

There were ambivalences however, in that some principals’ sense of unease and dissatisfaction grew with the size of the grant and the increased ‘red tape’ or bureaucratic burden. Overall, principals reported high levels of paperwork and red tape (Fitzgerald et al., 2018; Gavin & Stacey, 2023; Niesche et al., 2023), and in this study, the increased red tape was primarily located within the numerous applications for competitive funding from the government. Furthermore, their capacities to make autonomous decisions were constrained to some extent. Despite operating in so-called autonomous and decentralised contexts, interviewees reported a perception of punitive or punishing outcomes when making self-managing decisions with their budgets (e.g. saving additional money in the budget for capital projects, which were insufficiently funded by the state).

Competitive grant applications were anchored within, and driven by, systemic-wide inequity in school funding. The majority of school principals reported significant funding shortfalls, which prompted and propelled their competitive grant writing labour. The funding they were applying for was to pay for projects or services that might be considered rudimentary, such as school infrastructure for functioning toilets, roofs, retaining walls and the like; so too, they were applying for disability supports grants, and wellbeing projects for their students. These are resources that ideally would be considered fundamental within public education. Arguably, and as other scholars have pointed to, ensuring that public schools are well-funded and resourced is important for broader societal equity and mobility (Connell, 2013; Mills et al., 2022; OECD, 2011; Perry, 2009).

In the interviews, the funding system was described as adversarial, competitive and punitive in its approach. The competitive applications increased and intensified principals’ workload, as interviewees were investing considerable personal and professional time into applications, and the majority of principals felt this detracted from their core work as school principal. Albeit this was an ambivalent position because many believed it was necessary to maintain their school competitiveness within the market, presenting a ‘double bind’ (Le Feuvre et al., 2023). For many it was ‘a part of the job’, whilst simultaneously questioning why they needed to engage in highly competitive applications for services or projects that should be considered basic or rudimentary. The competitive grant writing is, we argue, critically reshaping their role as an educator and school leader, in detrimental ways, particularly in the context of autonomous and under-funded public schools.

Data availability

The dataset is not available in a public repository at time of writing but it will be considered at a later date once concluded.

Notes

ACARA (2021) lists the six needs-based loadings (p. 116).

The majority of schools classified as ‘high-fee’ are Independent schools, rather than Catholic private schools. However, there is wide variation in tuition fees at Independent schools.

We focus on these highly populated states/territories as the majority of interviewees are located here.

The state of Victoria led the way with school decentralisation in the 1990s with the Education Self-Governing School Act (Parliament of Victoria, 1998).

Public schools in Victoria reportedly maintain the highest cost for parents via ‘voluntary fees’ (Grace, 2024).

This paper does not critique the Index for reasons of brevity. For a critique of how measures are calculated and applied (see Schulz, 2005).

References

ABS. (2023). Schools 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2024, from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/schools/latest-release#:~:text=four%20in%20five%20(82.4%25),This%20is%205.8%20percentage%20points

ACARA. (2010). “My School” technical paper—index of community socio-educational advantage (ICSEA). http://www.myschool.edu.au/Resources.aspx

ACARA. (2018). ICSEA 2017: Technical report (research and development) February 2018. Retrieved from www.myschool.edu.au

ACARA. (2019). Data standards manual: Student background characteristics. For use by schools and school systems, test administration authorities, assessment contractors. 2019 edition. Retrieved from Sydney, New South Wales.

ACARA. (2021). National report on schooling in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.acara.edu.au/reporting/national-report-on-schooling-in-australia

ACARA. (2024). Technical and statistical information. Retrieved from https://www.myschool.edu.au/technical-and-statistical-information

AEU. (2024). Ending the capital funding divide in Australia’s schools. Retrieved from https://www.aeufederal.org.au/news-media/news/2024/ending-capital-funding-divide-australias-schools

Australian Government. (2011). Australian government review of funding for schooling: Final report december 2011. (The Gonski review). Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations

Australian Government. (2024a). Federal register of legislation: Australian education act 2013. Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.au/C2013A00067/latest/downloads

Australian Government. (2024b). How schools are funded. Retrieved from https://www.education.gov.au/schooling/how-schools-are-funded

Australian Government. (2024c). Schools upgrade fund. Retrieved from https://www.education.gov.au/newsroom/articles/apply-round-2-schools-upgrade-fund

Baker, B. D. (2016). Does money matter in education? (Second Edition). Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED563793.pdf

Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy, 18(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093022000043065

Beazley, J. (2023). Australian public school funding falls behind private schools as states fail to meet targets. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/jul/24/australian-public-school-funding-falls-behind-as-states-fail-to-meet-targets

Beazley, J., & Cassidy, C. (2023). Private school funding increased twice as much as public schools’ in decade after Gonski, data shows. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/education/2023/jul/17/gonski-review-government-funding-private-public-schools

Blackmore, J. (2005). ‘The emperor has no clothes’: Professionalism, performativity and educational leadership in high-risk postmodern times. In J. Collard & C. Reynolds (Eds.), Leadership, gender and culture in education (pp. 173–194). Open University Press.

Blackmore, J., MacDonald, K., Keddie, A., Gobby, B., Wilkinson, J., Eacott, S., & Niesche, R. (2023). Election or selection? School autonomy reform, governance and the politics of school councils. Journal of Education Policy, 38(4), 547–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2021.2022766

Bonnor, C., & Shepherd, B. (2016). Uneven playing field: The state of Australia’s schools. Retrieved from http://cpd.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/The-State-of-Australias-Schools.pdf

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

Chesters, J. (2018). The marketisation of education in Australia: Does investment in private schooling improve post-school outcomes? Australian Journal of Social Issues, 53(2), 139–157. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.643296090724817

Chiu, M. M., & Khoo, L. (2005). Effects of resources, inequality, and privilege bias on achievement: Country, school, and student level analyses. American Educational Research Journal, 42(4), 575–603.

Connell, R. (2013). Why do market ‘reforms’ persistently increase inequality? Discourse, 34(2), 279.

Connors, L., & McMorrow, J. (2015). Australian education review: Imperatives in schools funding: Equity, sustainability and achievement. Retrieved from https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1024&context=aer

Creagh, S., Thompson, G., Mockler, N., Stacey, M., & Hogan, A. (2023). Workload, work intensification and time poverty for teachers and school leaders: A systematic research synthesis. Educational Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2023.2196607

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2023). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE Publications Inc.

Department of Education QLD. (2022). Queensland state schools resourcing framework guide. Retrieved from https://qed.qld.gov.au/our-publications/managementandframeworks/Documents/state-school-resourcing/state-schools-resourcing-framework-guide.pdf

DET VIC. (2023). School operations: School-funded capital projects. Retrieved December 15, 2023, from https://www2.education.vic.gov.au/pal/school-funded-capital-projects/policy

DET VIC. (2024). Finance manual—financial management for schools. Retrieved from https://www2.education.vic.gov.au/pal/finance-manual/policy

Enright, E., Hogan, A., & Rossi, T. (2020). The commercial school heterarchy. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2020.1722423

Fallon, G., & Poole, W. (2014). The emergence of a market-driven funding mechanism in K-12 education in British Columbia: Creeping privatization and the eclipse of equity. Journal of Education Policy, 29(3), 302–322.

Fitzgerald, S., McGrath-Champ, S., Stacey, M., Wilson, R., & Gavin, M. (2018). Intensification of teachers’ work under devolution: A ‘Tsunami’ of paperwork. Journal of Industrial Relations, 61(5), 613–636. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185618801396

Gavin, M., & Stacey, M. (2023). Enacting autonomy reform in schools: The re-shaping of roles and relationships under local schools, local decisions. Journal of Educational Change, 24(3), 501–523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-022-09455-5

Gobby, B. (2013). Principal self-government and subjectification: The exercise of principal autonomy in the Western Australian Independent Public Schools Programme. Critical Studies in Education, 54(3), 273–285.

Gobby, B., Keddie, A., & Blackmore, J. (2018). Professionalism and competing responsibilities: Moderating competitive performativity in school autonomy reform. Journal of Educational Administration & History, 50(3), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2017.1399864

Grace, R. (2024). Public schools got $570 per student last year—their private rivals raked in $15,000. Retrieved from https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/public-schools-got-570-per-student-last-year-their-private-rivals-raked-in-15-000-20240229-p5f8up.html

Hogan, A., Gerrard, J., & Di Gregorio, E. (2023). Philanthropy, marketing disadvantage and the enterprising public school. The Australian Educational Researcher, 50(3), 763–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00524-5

Holloway, J., & Keddie, A. (2020). Competing locals in an autonomous schooling system: The fracturing of the ‘social’ in social justice. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 48(5), 786–801. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143219836681

Hunter, F. (2019). Public schools lack resources to meet needs of ‘invisible’ students with disabilities. Retrieved from https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/publicschools-lack-resources-to-meet-needs-of-invisible-students-with-disabilities-20190215-p50y0f.html

Keddie, A. (2016). School autonomy as ‘the way of the future’: Issues of equity, public purpose and moral leadership. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 44(5), 713.

Keddie, A., Gobby, B., & Wilkins, C. (2018). School autonomy reform in Queensland: Governance, freedom and the entrepreneurial leader. School Leadership & Management, 38(4), 378–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2017.1411901

Lamb, S., Jackson, J., Walstab, A., & Huo, S. (2015). Educational opportunity in Australia 2015: Who succeeds and who misses out. Retrieved from www.vu.edu.au/centre-for-international-research-on-education-systems-cires

Le Feuvre, L., Hogan, A., Thompson, G., & Mockler, N. (2023). Marketing Australian public schools: The double bind of the public school principal. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 43(2), 599–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2021.1953440

MacDonald, K., Keddie, A., Blackmore, J., Mahoney, C., Wilkinson, J., Gobby, B., Niesche, R., & Eacott, S. (2023). School autonomy reform and social justice: A policy overview of Australian public education (1970s to present). The Australian Educational Researcher, 50(2), 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-021-00482-4

Mills, M., Riddle, S., McGregor, G., & Howell, A. (2022). Towards an understanding of curricular justice and democratic schooling. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 54(3), 345–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2021.1977262

Mockler, N., Thompson, G., & Hogan, A. (2023). ‘If you can’t beat them, join them’: Utility, markets and the absent entrepreneur. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 44(3), 467–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2023.2167701

Murillo, F. J., & Roman, M. (2011). School infrastructure and resources do matter: Analysis of the incidence of school resources on the performance of Latin American Students. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 22(1), 29–50.

News, S. (2023). Almost no public school in the country fully funded: Jason Clare. Retrieved December 12, 2023, from https://www.skynews.com.au/australia-news/politics/almost-no-public-school-in-the-country-fully-funded-jason-clare/video/69c6794a869a64b2a4bb7da7cb58c7cf

Niesche, R. (2010). Discipline through documentation: A form of governmentality for school principals. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 13(3), 249–263.

Niesche, R. (2013). Foucault, counter-conduct and school leadership as a form of political subjectivity. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 45(2), 144–158.

Niesche, R., Eacott, S., Keddie, A., Gobby, B., MacDonald, K., Wilkinson, J., & Blackmore, J. (2023). Principals’ perceptions of school autonomy and educational leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 51(6), 1260–1277.

OECD. (2011). Divided we stand: Why inequality keeps rising. OECD.

OECD. (2013). PISA 2012 results: What makes schools successful? Resources, policies and practices (volume IV). Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/pisa/keyfindings/pisa-2012-results-volume-IV.pdf

OECD. (2020). School autonomy. Retrieved from https://gpseducation.oecd.org/revieweducationpolicies/#!node=41701&filter=all

Parliament of Victoria. (1998). Education (self-governing schools) act 1998. Parliament of Victoria.

Perry, L. (2009). Characteristics of equitable systems of education: A cross-national analysis. European Education, 41(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.2753/EUE1056-4934410104

Perry, L. B., Lubienski, C., & Ladwig, J. (2016). How do learning environments vary by school sector and socioeconomic composition? Evidence from Australian students. Australian Journal of Education, 60(3), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944116666519

Perry, L. B., Yoon, E. S., Sciffer, M., & Lubienski, C. (2024). The impact of marketization on school segregation and educational equity and effectiveness: Evidence from Australia and Canada. International Journal of Comparative Sociology. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207152241227810

Poole, W., Fallon, G., & Sen, V. (2020). Privatised sources of funding and the spatiality of inequities in public education. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 52(1), 124–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2019.1689105

Powers, J. M. (2004). High-Stakes accountability and equity: Using evidence from California’s public schools accountability act to address the issues in Williams vs. State of California. American Educational Research Journal, 41(4), 763–795. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312041004763

Preston, B. (2023). Report on a national symposium funding, equity and achievement in Australian schools. The University of Melbourne.

Rorris, A. (2021). Investing in schools—funding the future. Retrieved from https://www.aeufederal.org.au/application/files/5716/2278/1619/AEU197_Investing_in_Schools_Report_v5_REV.pdf

Rorris, A. (2023). How school funding fails public schools: How to change for the better. Retrieved from https://www.aeufederal.org.au/application/files/3817/0018/3742/Rorris_FundingFailsPublicSchools.pdf

Rowe, E., & Perry, L.B. (2020a). Private financing in urban public schools: inequalities in a stratified education marketplace. The Australian Educational Researcher, 47(1), 19-37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00328-0

Rowe, E. & Perry, L.B. (2020b). Inequalities in the private funding of public schools: parent financial contributions and school socioeconomic status. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 52(1), 42-59. 10.1080/00220620.2019.1689234

Rowe, E. & Perry, L.B. (2022). Voluntary school fees in segregated public schools: how selective public schools turbo-charge inequity and funding gaps. Comparative Education 58(1) 106-123 10.1080/03050068.2021.1942359

Rowe, E. & Di Gregorio, E. (In Press). Grant Chaser and Revenue Raiser: public school principals and the limitations of philanthropic funding. Australian Educational Researcher. In Press.

Schulz, W. (2005). Measuring the socio-economic background of students and its effect on achievement in PISA 2000 and PISA 2003. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, 7–11 April 2005.

Smith, C., Tani, M., Yates, S., & Dickinson, H. (2023). Successful school interventions for students with disability during covid-19: Empirical evidence from Australia. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 32(3), 367–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-022-00659-0

Stacey, M., McGrath-Champ, S., & Wilson, R. (2023). Teacher attributions of workload increase in public sector schools: Reflections on change and policy development. Journal of Educational Change, 24(4), 971–993. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-022-09476-0

Stewart, D. J., & Russo, C. J. (2001). A comparative analysis of funding non-government schools in Australia and the United States. Education and the Law, 13(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/09539960120046736

Thompson, G., Hogan, A., & Rahimi, M. (2019). Private funding in Australian public schools: A problem of equity. The Australian Educational Researcher. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00319-1

Ting, I., Palmer, A., & Scott, N. (2019). Rich school, poor school: Australia’s great education divide. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-08-13/rich-school-poor-school-australias-great-education-divide/11383384#schoolmap

VSBA. (2023a). Inclusive schools fund. Retrieved from https://www.schoolbuildings.vic.gov.au/inclusive-schools-fund

VSBA. (2023b). School shade sails fund. Retrieved March 14, 2023, from https://www.schoolbuildings.vic.gov.au/school-shade-sails-fund

Wark, T. (2024). AAP FactCheck: Labor’s school funding pledge may trip on ‘loophole’. Retrieved from https://www.aap.com.au/factcheck/labors-school-funding-pledge-may-trip-on-loophole/

Watson, L., & Ryan, C. (2010). Choosers and losers: The impact of government subsidies on Australian secondary schools. Australian Journal of Education, 54(1), 86–107.

Windle, J. (2009). The limits of school choice: Some implications for accountability of selective practices and positional competition in Australian education. Critical Studies in Education, 50(3), 231–246.

Windle, J., & Stratton, G. (2013). Equity for sale: Ethical consumption in a school-choice regime. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2013.770247

Winton, S. (2018a). Challenging fundraising, challenging inequity: Contextual constraints on advocacy groups’ policy influence. Critical Studies in Education, 59(1), 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1176062

Winton, S. (2018b). Coordinating policy layers of school fundraising in Toronto, Ontario, Canada: An institutional ethnography. Educational Policy. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904818807331

Yoon, E. S., Young, J., & Livingston, E. (2019). From bake sales to million-dollar school fundraising campaigns: The new inequity. Journal of Educational Administration and History. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2019.1685473

Zipin, L., Sellar, S., Brennan, M., & Gale, T. (2015). Educating for futures in marginalized regions: A sociological framework for rethinking and researching aspirations. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 47(3), 227–246.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the interviewees who granted us their time and intellectual contributions for this project. This paper was supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council. This project has human ethics approval from Deakin University. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback on the first draft of this paper.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The study is funded by the Australian Research Council DECRA (DE210100513) from 2021 to 2024.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both named authors contributed to the work. The paper is based on Emma Rowe’s funded study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval has been received from Deakin University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (DUHREC). Project number is: HAE-21-132. The study adheres to the ethics principles.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rowe, E., Langman, S. Competitive grants in autonomous public schools: how school principals are labouring for public school funding. Aust. Educ. Res. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-024-00746-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-024-00746-9