Abstract

There is a high prevalence of adolescent girls with ovulatory menstrual (OM) dysfunction, which is associated with school absenteeism and mental health challenges. Low menstrual health literacy among this group has evoked calls to review OM health education. This qualitative study sought to explore gaps in current OM health education and to validate a holistic school-based OM health literacy program named My Vital Cycles®. Findings are based on 19 written reflections, six focus group discussions and three interviews conducted with 28 girls aged 14–18 years from 11 schools, and five mothers. Six themes compared current OM health education with My Vital Cycles®: understating health, comprehensiveness, resources, teaching, parents and cycle tracking. Future refinements to the program comprised: inclusion of the complete reproductive lifespan, use of visual media and developing a mobile application. These findings inform future research in a whole school approach, strengths-based teaching and changes in the health curriculum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health literacy includes the cognitive and social skills to enable an individual to maintain good personal health through gathering, understanding and using information accordingly (World Health Organization [WHO], 2009). The ovulatory-menstrual (OM) cycle is a “vital sign” of good health for reproductively maturing females (American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists [ACOG], 2015). Skills in observing, interpreting and responding to OM cycle biomarkers form a specific health literacy. Therefore, OM health literacy can be defined as firstly, the discipline of applying OM cycle knowledge and skills to monitor personal health and manage fertility with due cognisance of life stage and/or stressors; and secondly, confident engagement and active involvement with healthcare providers to maintain and/or restore good health (Roux et al., 2023).

However, amongst 15–19 year old post-menarcheal adolescents in Australia, self-reported prevalence of premenstrual symptoms, pain, mood disturbances and atypical bleeds were 96%, 93%, 73% and 41%, respectively (Parker et al., 2010). Elsewhere, OM difficulties have been associated with mental health struggles (Bisaga et al., 2002; van Iersel et al., 2016) including poor self-esteem (Drosdzol-Cop et al., 2017), body dissatisfaction (Ambresin et al., 2012), eating disorders (Ålgars et al., 2014) and non-suicidal self-injury (Liu et al., 2018).

Recent studies indicate menstrual health literacy levels are low (Holmes et al., 2021), with adolescents unable to assess whether their period was typical (Isguven et al., 2015; Randhawa et al., 2021). Several studies have highlighted the need for a stronger provision of school-based OM health education (Armour et al., 2021; Holmes et al., 2021; Isguven et al., 2015; Randhawa et al., 2021). Schools are an attractive choice for providing OM health education. They provide a cost-effective and efficient solution with wide reach (Li et al., 2020), they can help students develop skills to live well (Wyn, 2007), and they promote wellbeing (Powell et al., 2018). Schools are also interested in addressing absenteeism and reduced academic performance associated with OM problems (Armour et al., 2019).

Some focus on menstrual health is included in the Australian Health and Physical Education (HPE) curriculum (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], 2023). In addition, there are specific programs and resources, with individual schools opting to participate, for example Period Talk™ (Lawton, 2023), Menstruation Matters (Armour et al., 2022) and Periods Pain & Endometriosis Program PPEP Talk® (Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia, 2023). Recommendations from a systematic literature review of 16 international and comparable school-based menstrual health interventions concluded that future programs would benefit from adopting a whole person or biopsychosocial perspective; implementing a positive or strengths-based approach; prioritising ovulation; moving from single issues to including other common OM difficulties; and involving parents and healthcare providers (Roux et al., 2021).

A formative research project was established to address OM health literacy by developing and trialling a school-based OM health literacy program based on the whole person (Roux et al., 2019). Considering the above recommendations (Roux et al., 2021), the content of the pre-trial draft program was validated by a Delphi panel of health and education professionals (Roux et al., 2022).

The program was mapped to the Western Australian HPE curricula for Years 8 to 10 (School Curriculum and Standards Authority, 2023), and thereby extended OM health beyond the puberty education of Years 5 and 6. Since the Western Australian and Australian HPE curricula use Nutbeam’s Health Outcome Model (Nutbeam, 2000), its sequential and progressive acquisition of health literacy across three domains was embedded in the program. This Model begins with the functional health literacy domain (with skills of investigating and understanding information), then progresses to the interactive health literacy domain (with skills of personally applying knowledge and engaging with healthcare providers) and finishes with the critical health literacy domain (with skills of critically appraising information, problem-solving and socio-cultural awareness) (Nutbeam, 2000).

Implementing a strengths-based approach and involving parents and healthcare providers were achieved by tailoring the program to the WHO’s Health Promoting School (HPS) framework (Sawyer et al., 2021; WHO, 2021). The HPS framework describes a whole-school approach to health whereby a school consistently strengthens itself as a safe, healthy setting of education.

This article reports on a study within a broader formative research project (Roux et al., 2019) and aimed to.

-

(a)

face validate the program by students and parents; and

-

(b)

report their perspectives on current OM health education.

The participants’ face validation is their subjective judgement on whether the program complied to the recommendations (Drost, 2011) of the systematic literature review (Roux et al., 2021). They voted to name the program ‘My Vital Cycles®’ (MVC). By partnering with students and parents, students’ right to participate in matters that affect them was recognised (Powell et al., 2018).

The authors use terms such as females, girls and women in relation to sex (i.e. biological characteristics or reproductive organs). It is recognised that this may differ from gender identity. For example, someone who menstruates may or may not identify as “female”. The authors believe anyone who has cycles should have the information and skills necessary to manage them.

Methods

MVC consists of nine face-to-face lessons, of which six are taught within the HPE curriculum, two are learnt at home and one is a school-based event involving parents. The curriculum lessons are supported with class discussions and worksheets. OM health literacy is assessed using a validated questionnaire (Roux et al., 2023). Table 1 provides an outline of MVC’s lessons and delivery location.

Design

The study design used written reflections, focus group discussions (FGDs) and interviews with adolescent girls and mothers. Given COVID restrictions at the time of this study, this was considered the most practical and flexible design, albeit that interviews removed the possibility of interactions between participants. This study was guided by COREQ (Tong et al., 2007). Ethics approval was provided by Curtin’s Human Research Ethics Committee (approval HRE2018-0101) and Catholic Education of Western Australia (approval RP2018/44).

Participants

Participants were recruited through the Consumer and Community Health Research Network (CCHRN) established by the Western Australian Health Translation Network. The CCHRN matched the study to its registered consumers and invited them to participate. Twenty-eight Independent and Catholic schools in the Perth metropolitan area were also approached directly. Females aged 15–18 years and their parents were eligible to participate.

Potential participants who expressed interest were provided a detailed information statement, which described the study’s aims, requirements of participation and data management. For females below the age of 18 years, written parental consent was obtained together with the child’s assent to participate. Females over the age of 18 years signed their own consent form. In total, 28 girls, five mothers and no fathers participated.

Data collection

Prior to FGDs and interviews, an MVC booklet containing all lessons was given to each girl. Participants were given three weeks to write their anonymous reflections directly into the booklet and return it at the end of the discussion.

A semi-structured question guide was developed (see Table 2). The first part enquired about girls’ experiences of their menstrual health education. The second part asked girls’ and parents’ views of the MVC program, referring to their booklet notations as an aide. Open questions and prompts were used to elicit rich participant-led discussions (Galletta & Cross, 2013; Gill et al., 2008).

FGDs of ≈45 min were conducted face-to-face, and interviews of ≈30 min were either face-to-face or via telephone. They were facilitated by Researcher 1, audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Where FGDs were held at a school, a private area was provided, and the school’s healthcare professional was on call. For community-based discussions, a mother was present. No participants took up the offer to review their transcript. Pseudonyms were given to protect participant identity.

Data analysis

Studies in children’s wellbeing increasingly use a grounded approach because they are based on the subjects’ own first-hand experiences (Powell et al., 2018). Therefore an inductive approach to the interpretation and analysis of data was used.

Researcher 1 thematically coded the transcripts line-by-line into NVivo®. A six-phase protocol was followed to thematically analyse the transcripts (Braun & Clarke, 2013). Data units (words, expressions or sentences) were analysed using content analysis (Kondracki et al., 2002). This facilitated qualitative description (Neergaard et al., 2009) through systematic coding and categorising of textual data (Vaismoradi et al., 2013) into common themes which represent participants’ experiences and reflections (Willis et al., 2016). Constant comparison analysis strategies were used to analyse participants’ responses. This involved coding early discussions and continually comparing and sorting the codes as more data were collected (Fram, 2013).

Researchers 1 and 3 undertook initial analysis by reviewing each code. Using hard-copy printouts, preliminary codings were discussed with the research team. Coding was revised and re-examined by the team to check interpretations and conclusions. Connections to other code categories were then explored to find relationships that generated themes (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Data dependability was maintained by reference to the raw transcripts which facilitated the team’s final refinement of the themes and subthemes. To minimise bias, Researcher 1 continuously evaluated and reflected on her role within the study and gave regular commentary to reflect on key areas of interests, the participants’ language and interactions (Biggerstaff & Thompson, 2008).

Results

Characteristics of the participants and schools

Six FGDs were conducted, of which two included mother-daughter pairs. Three interviews were conducted, of which two were mother-daughter pairs and one mother-only interview. The average age of the girls was 16 years (range 14–18). Nineteen notated booklets were returned. Table 3 describes the characteristics of the schools the girls attended.

Six themes were identified: understating health, comprehensiveness, resources, teaching, parents and cycle tracking. The 23 subthemes are presented with illustrative quotes in Table 4.

Understating health

Across all sectors, girls and mothers agreed that menstrual health education was downplayed. One mother opined: ‘… they are young women with a right to know how their body works’ (Mother_Girl). Schools were perceived to assign priority to other subjects rather than health. As Lucy mused: ‘We get taught a lot of things in school that we do not use in everyday life’ (Lucy-Age15_Coed). Within the HPE curriculum, other subjects were given precedence over OM health, which left Layla rhetorically asking: ‘Are we going to spend 50 years of our life having car crashes for a week every month?’ (Layla-Age18_Girl). Low value was placed on health education in general, with Julienne admitting: ‘Most of us catch up on studies in other subjects because it’s a really chill class’ (Julienne-Age14_Coed). In contrast, the MVC program encouraged learning. As one mother explained:

I like that this [MVC] is kind of giving value to saying, ‘For half of the population, this is what their body's going through’. But we've never really put much focus on it because our institutions are run by men. So I really like that it's saying we're not just expecting you to go through high school, just this being an inconvenience that you silently try and deal with. That it is a conversation, and a lifestyle. (Mother_Coed)

Overall, participants agreed that OM health education had to date received insufficient priority in preparing girls to live future healthy lives.

Comprehensiveness

There was agreement that the cycle was an important enduring feature through life. Whilst menstruation was usually taught around menarche, ovulation was omitted. Lucy explained: ‘Like I've heard of the word, but I just didn’t know what it was’ (Lucy-Age15_Coed). In Luna’s opinion, ‘they need to know of course, because otherwise people go, “oh my God, what’s going on?”’ (Luna-Age18_Coed). In contrast, MVC prioritised ovulation and distinguished different bleeds.

Regarding the current HPE curriculum, the girls agreed that they did not know how to personally apply information. As Charlotte explained:

There’s a disconnect between like transferring that knowledge from sort of like theoretical classroom stuff, sort of one-model-fits-all, to girls actually understanding about their own bodies and how this applies in real life. (Charlotte-Age18_Coed)

Furthermore, discussions in classes were not forthcoming. Even in an all-girls school, Aurora advised: ‘we did learn stuff like this, but even so the girls were kind of like not really into it ‘cos it was more of a personal subject’ (Aurora-Age16_Girl). The girls also advised that common OM cycle difficulties were not taught. In contrast, MVC covered dysmenorrhoea, abnormal bleeding and premenstrual syndrome, and its biopsychosocial approach connected the OM cycle with mental health. As Charlotte explained:

If you could recognise like where you have a lot of hormonal change and you found yourself like feeling really down, it would be helpful then say applying it to like later on where you have another big hormonal change, like if you get pregnant, or menopause, or something. Like that awareness would help you talk to a doctor more. (Charlotte-Age18_Coed)

Furthermore, one mother commented how MVC initiated biopsychosocial conversations in Lessons 1 and 2:

Education is a really great priority. Fantastic. Have a career, and so on. But nobody ever discusses, ‘how are you going to fit in a family with that?’ and ‘how are you going to work out the competing priorities?’ (Mother_Girl)

However, she recommended ‘At some point menopause is going to kick in and I know nothing about it. So that could be taught too’ (Mother_Girl). Whilst MVC promoted fertility care, it had overlooked other milestones.

Resources

Overall, the girls reported that current menstrual health resources were unrelatable, irrelevant to their developmental stage or a repeat of previous years. Although MVC was reported to be appropriately targeted to their developmental stage, incorporating interactive activities and visual media such as video clips was consistently recommended.

Teaching

The girls reported that the gender and expertise of teachers were important. Most agreed with Saskia’s opinion that: ‘It’s just kind of like a weird topic for men to talk about’ (Saskia-Age18_Girl). Indignance was expressed on rule enforcement prohibiting toilet breaks, as London reflected:

They're like, ‘No. Kids stay in class,’ and stuff like that. If a girl needs to go, a girl's got to go. Yeah. Do you want me to just sit in a pool of blood? (London-Age15_Coed)

The inclusion of healthcare experts and school nurses as elements of MVC’s applied HPS framework was acknowledged.

Parents

Although mothers were the primary source of information, their own knowledge was lacking. Ruby shared her mother’s reaction to the MVC booklet: ‘she was intrigued, but I feel like she didn't really understand anything in this because she didn’t know either’ (Ruby-Age15_Coed). Ida reported her father’s reaction to menstrual discussions:

It's very much like, ‘Keep quiet until there's all girls.’ I love my Dad, but he's clueless about stuff like this. (Ida-Age15_Coed)

MVC’s inclusion of parents in Lessons 1 and 8 garnered approval for parental education.

Cycle tracking

Mobile applications were favoured for cycle tracking because of their convenience. However, the majority of girls admitted that their apps inaccurately predicted their period due date, with concerns expressed for the use of their private data. MVC presented charting as journal writing to personalise cycle theory. The discipline required received mixed views. Ruby declared: ‘I love drawing and writing stuff down’ (Ruby-Age15_Coed), whilst Maxine maintained: ‘I feel like that’s quite a commitment’ (Maxine-Age15_Girl). Charlotte suggested: ‘maybe if it was possible for the program to have their own App’ (Charlotte-Age18_Coed).

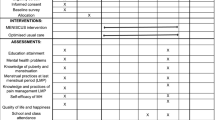

The elements of face validity and suggestions for improvements in MVC are summarised in Table 5.

Discussion

What’s going on …

… with family

Using the HPS framework (Sawyer et al., 2021; WHO, 2021), MVC invited the inclusion and education of parents. Participants considered this a commendable redress of poor knowledge and negative attitudes given that daughters turn to their mothers for guidance about an essentially female phenomenon that they both personally experience (Afsari et al., 2017; Isguven et al., 2015; Koff & Rierdan, 1995; Li et al., 2020). Parental education may help address the prevalence of poor knowledge observed in Australia (Hammarberg et al., 2013; Hampton et al., 2013), as elsewhere (Ayoola et al., 2016; Bunting et al., 2013; Daniluk et al., 2012; Lundsberg et al., 2014; Pedro et al., 2018). Similarly, MVC’s strengths-based approach may address potential negative attitudes towards menstruation which can be conveyed from mother to daughter (Chrisler & Gorman, 2016; Stubbs & Costos, 2004).

No fathers participated in this study, yet their role was raised. Girls and mothers deemed fathers’ knowledge inadequate, as one study confirms (Girling et al., 2018). A preference for fathers to be silently supportive was similarly reported (Koff & Rierdan, 1995). However, it was suggested that fathers could be encouraged to improve their knowledge of OM health through invitation to MVC’s parent school event (see Table 5).

… with schools

Similar to this study, participants from other studies reported that school-based health education could extend beyond minimal details of menstruation (Koff & Rierdan, 1995; Li et al., 2020) to include menstrual problems, seeking medical care (Li et al., 2020) and ovulation. Improvements to OM health education would include developing self-knowledge in students and expanding their capacity towards decision-making and action-taking (Paynter & Bruce, 2013).

MVC offers a whole of OM cycle education, thereby avoiding a narrow fixation on menstruation and associated dysfunctions. It positions menstruation as consequential to the cycle’s main event of ovulation in the absence of pregnancy (Vigil et al., 2006). This knowledge enables girls to recognise which bleeds are menstrual and which are anovulatory (Klaus & Martin, 1989; Rosenfield, 2013). Participants consistently liked how MVC refocused the whole of the OM cycle as a sign of good health in and of itself. Taking this strengths-based approach (Wilding & Griffey, 2015), MVC was regarded as redressing negative attitudes towards menstruation whilst realistically addressing menstrual difficulties to restore good health. This contrasts to a deficit-oriented approach (Gharabaghi & Anderson-Nathe, 2017) which tends to focus exclusively on menstruation and frame it as a problem.

Both girls and mothers highlighted the current lack of HPE education around future fertility.This is concerning since 77% of Australian senior school students want to have children (Heywood et al., 2016). They valued the inclusion of fertility in MVC. Furthermore, MVC lessons 1 and 2 facilitated structured conversations about education and future plans including family formation (Mackinnon, 1995), which was interpreted as the balancing of careers with children. MVC’s critical health literacy domain connected the biology of personal fertility awareness with socio-cultural considerations (Littleton, 2014). This can facilitate informed decision-making (Boivin et al., 2013) and allow young people to manage their reproductive lives.

Inclusion of the complete reproductive lifespan was jointly and independently suggested by girls and mothers to refine MVC. Their reflections centred upon the extensive length of time in which women have OM cycles, and the milestones encountered such as pregnancy, lactation and menopause.

Similar to other studies, girls reported that some teachers obstructed their toilet access, which heightened their distress with uncontrollable leakages (Li et al., 2020) and a negative perception of teachers regarding their lesson preparation and comfort in delivery (Ezer et al., 2019; Pound et al., 2016). A strong preference for female teachers was indicated. In addition, girls preferred lessons to be delivered by health professional experts (Isguven et al., 2015; Li et al., 2020; Pound et al., 2016), notably guest speakers (Ezer et al., 2019).

MVC’s adoption of the HPS framework addresses these matters because it invites connection with multiple sources of positive support including teachers, parents, the school’s healthcare team and its external community of health providers. Given the girls’ reports of current high quality of school nurses, the HPS framework could therefore assure continuity of care for menstrual difficulties, and define personal and professional boundaries (Pound et al., 2016) by including them and external healthcare providers in formal teaching. This connectedness may collectively redress the shame of menstruation (Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2013; Wister et al., 2013) given that information alone is rarely sufficient to address stigmatised subjects (Bulanda et al., 2014).

… in my body

The female reproductive system is predominantly internal, which can be challenging for girls to apply abstract information to their own maturing bodies (Koff & Rierdan, 1995). They consistently expressed a desire to understand how their own bodies functioned both in the present time and for the long reproductive life ahead. Furthermore, most recognised the OM cycle’s impact on mental health, and valued the way MVC integrated the two. In short, girls wanted to personalise their education.

In the absence of reliable and relatable education from either their mothers or schools, girls resorted to mobile applications for information and to gain some semblance of control of their periods. However, most found that their mobile applications were not useful in predicting periods. The variability of the follicular phase means it is impossible for calendar-based applications to predict periods accurately (Johnson et al., 2018). The usefulness of applications using adaptive algorithms based on personal historical data remains limited, particularly for adolescents.

Nonetheless, charting cycles is recommended for adolescent girls (ACOG, 2015; González, 2017; Vigil et al., 2006). MVC offered creative journaling to encourage interactive health literacy. Girls understood how this would enable them to compare their own cycles with normal parameters and thereby request timely medical care. Most girls recognised that learning to chart and maintaining charts would help them know ‘what’s going in my body’. However, discipline is required to gain the requisite self-awareness.

Strengths and limitations

Data were collected through annotated booklets, interviews and FGDs. Multiple methods of data collection for the same phenomenon adds validity (Cohen et al., 2017). For example, interviews reduced the potential privileging of self-assured girls in a FGD setting of social dynamics and pressures to present a consensus (Galliott & Graham, 2016; Powell et al., 2018). In addition, anonymous writing enabled less assertive girls to record their opinions honestly. It is however a limitation that first-hand experiences of the MVC program were not possible which would likely render richer perspectives.

The range of ages adds validity. The immediate experiences of girls whose ovulatory processes were likely just beginning are tempered with the comfortable reflections of older girls (Schmitt et al., 2021).

Furthermore, government and non-government schools were represented, across different ICSEA scales.

Face validation is an early-stage evaluation. For example, selection bias may be present as girls who were interested in OM health may have been more likely to participate and provide positive feedback on MVC. Stratified sampling in future studies for similar proportions of girls who are and are not interested in the program may reduce the impact of this bias.

Additionally, data was collected from metropolitan Western Australia and cannot be generalised. Robustness would be improved by extending research into different locations and populations.

Furthermore, the experiences and opinions of teachers and school healthcare providers merits further research, including how male teachers could improve their comfort in delivering OM health education.

Conclusion

Partnering with girls and mothers refined the validity of the MVC program in light of current gaps in OM health education. Its whole person perspective integrated biological and mental health. MVC’s strengths-based guidance on personal charting provided complete OM cycle instruction, including common OM difficulties, and thereby facilitated functional and interactive OM health literacy. The adoption of the HPS framework to include parents, the school healthcare team and community healthcare providers further supported interactive and critical OM health literacy. Fine-tuning of MVC would include adding milestones of the reproductive lifespan; creating additional group activities, videos and animations; developing a mobile application; and involving fathers. This study’s findings may inform improvements to OM health education, particularly by augmenting HPE curriculum content with complete OM cycle teaching from a biopsychosocial perspective, positive teaching styles and including parents, the school healthcare team and community healthcare providers in formal teaching.

References

Afsari, A., Mirghafourvand, M., Valizadeh, S., Abbasnezhadeh, M., & Galshi, M. (2017). The effects of educating mothers and girls on the girls’ attitudes toward puberty health: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine & Health, 29(2), 984–965.

Ålgars, M., Huang, L., Von Holle, A. F., Peat, C. M., Thornton, L. M., Lichtenstein, P., & Bulik, C. M. (2014). Binge eating and menstrual dysfunction. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 76(1), 19–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.11.011

Ambresin, A.-E., Belanger, R. E., Chamay, C., Berchtold, A., & Narring, F. (2012). Body dissatisfaction on top of depressive mood among adolescents with severe dysmenorrhea. Journal of Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology, 25(1), 19–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2011.06.014

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2015). American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee opinion No. 651: Menstruation in girls and adolescents: Using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 126(6), e143–e146. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001215

Armour, M., Hyman, M. S., Al-Dabbas, M., Parry, K., Ferfolja, T., Curry, C., MacMillan, F., Smith, C. A., & Holmes, K. (2021). Menstrual health literacy and management strategies in young women in Australia: A national online survey of young women aged 13–25 years. Journal of Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology, 34(2), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2020.11.007

Armour, M., Parry, K., Curry, C., Ferfolja, T., Parker, M. A., Farooqi, T., MacMillan, F., Smith, C., & Holmes, K. (2022). Evaluation of a web-based resource to improve menstrual health literacy and self-management in young women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 162, 111038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2022.111038

Armour, M., Parry, K., Manohar, N., Holmes, K., Ferfolja, T., Curry, C., MacMillan, F., & Smith, C. A. (2019). The prevalence and academic impact of dysmenorrhea in 21,573 young women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Women’s Health, 28(8), 1161–1171. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.7615

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2013). Guide to understanding 2013 Index of Community Socio-educational Advantage (ICSEA) values. Retrieved from https://www.myschool.edu.au/

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2023). Health and physical education (Version 8.4). Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/health-and-physical-education/

Ayoola, A. B., Zandee, G. L., & Adams, Y. J. (2016). Women’s knowledge of ovulation, the nenstrual cycle, and its associated reproductive changes. Birth, 43(3), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12237

Biggerstaff, D., & Thompson, A. R. (2008). Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA): A qualitative methodology of choice in healthcare research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 5(3), 214–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780880802314304

Bisaga, K., Petkova, E., Cheng, J., Davies, M., Feldman, J. F., & Whitaker, A. H. (2002). Menstrual functioning and psychopathology in a county-wide population of high school girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(10), 1197–1204. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200210000-00009

Boivin, J., Bunting, L., & Gameiro, S. (2013). Cassandra’s prophecy: a psychological perspective. Why we need to do more than just tell women. Reproductive BioMedicine Online, 27(1), 11–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.03.021

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. New York: Sage Publications Ltd.

Bulanda, J. J., Bruhn, C., Byro-Johnson, T., & Zentmyer, M. (2014). Addressing mental health stigma among young adolescents: Evaluation of a youth-led approach. Health & Social Work, 39(2), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlu008

Bunting, L., Tsibulsky, I., & Boivin, J. (2013). Fertility knowledge and beliefs about fertility treatment: Findings from the international fertility decision-making study. Human Reproduction, 28(2), 385–397. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/des402

Chrisler, J., & Gorman, J. (2016). Menstruation. Encyclopedia of Mental. Health, 3, 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-397045-9.00254-8

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis.

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. L. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). New York: Sage Publications Inc.

Daniluk, J. C., Koert, E., & Cheung, A. (2012). Childless women’s knowledge of fertility and assisted human reproduction: Identifying the gaps. Fertility & Sterility, 97(2), 420–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.11.046

Drosdzol-Cop, A., Bąk-Sosnowska, M., Sajdak, D., Białka, A., Kobiołka, A., Franik, G., & Skrzypulec-Plinta, V. (2017). Assessment of the menstrual cycle, eating disorders and self-esteem of Polish adolescents. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 38(1), 30–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/0167482X.2016.1216959

Drost, E. A. (2011). Validity and reliability in social science research. Education, Research and Perspectives, 38(1), 105–123.

Ezer, P., Kerr, L., Fisher, C. M., Heywood, W., & Lucke, J. (2019). Australian students’ experiences of sexuality education at school. Sex Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2019.1566896

Fram, S. M. (2013). The constant comparative analysis method outside of grounded theory. Qualitative Report, 18(1), 1–25.

Galletta, A., & Cross, W. E. (2013). Mastering the semi-structured interview and beyond: From research design to analysis and publication. New York University Press.

Galliott, N. Y., & Graham, L. J. (2016). Focusing on what counts: Using exploratory focus groups to enhance the development of an electronic survey in a mixed-methods research design. Australian Educational Researcher, 43(5), 567–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-016-0216-5

Gharabaghi, K., & Anderson-Nathe, B. (2017). Strength-based research in a deficits-oriented context. Child & Youth Services, 38(3), 177–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2017.1361661

Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E., & Chadwick, B. (2008). Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. British Dental Journal, 204(6), 291–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2008.192

Girling, J. E., Hawthorne, S. C. J., Marino, J. L., Nur Azurah, A. G., Grover, S. R., & Jayasinghe, Y. L. (2018). Paternal understanding of menstrual concerns in young women. Journal of Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology, 31(5), 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2018.04.001

González, S. (2017). The menstrual cycle as a vital sign: The use of Naprotechnology® in the evaluation and management of abnormal vaginal bleeding and PCOS in the adolescent. Issues in Law & Medicine, 32(2), 277–286.

Hammarberg, K., Setter, T., Norman, R. J., Holden, C. A., Michelmore, J., & Johnson, L. (2013). Knowledge about factors that influence fertility among Australians of reproductive age: A population-based survey. Fertility & Sterility, 99(2), 502–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.10.031

Hampton, K. D., Mazza, D., & Newton, J. M. (2013). Fertility-awareness knowledge, attitudes, and practices of women seeking fertility assistance. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(5), 1076–1084. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06095.x

Heywood, W., Pitts, M. K., Patrick, K., & Mitchell, A. (2016). Fertility knowledge and intentions to have children in a national study of Australian secondary school students. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 40(5), 462–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12562

Holmes, K., Curry, C., Sherry, F., & T., Parry, K., Smith, C., & Armour, M. (2021). Adolescent menstrual health literacy in low, middle and high-income countries: A narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 18(5), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052260

Isguven, P., Yoruk, G., & Cizmecioglu, F. M. (2015). Educational needs of adolescents regarding normal puberty and menstrual patterns. Journal of Clinical Research in Pediatric Endocrinology, 7(4), 312–322. https://doi.org/10.4274/jcrpe.2144

Johnson, S., Marriott, L., & Zinaman, M. (2018). Can apps and calendar methods predict ovulation with accuracy? Current Medical Research & Opinion, 34(9), 1587–1594. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2018.1475348

Johnston-Robledo, I., & Chrisler, J. (2013). The menstrual mark: Menstruation as social stigma. Sex Roles, 68(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0052-z

Klaus, H., & Martin, J. L. (1989). Recognition of ovulatory/anovulatory cycle pattern in adolescents by mucus self-detection. Journal of Adolescent Health Care, 10, 93–96.

Koff, E., & Rierdan, J. (1995). Preparing girls for menstruation: Recommendations from adolescent girls. Adolescence, 30(120), 795–795.

Kondracki, N. L., Wellman, N. S., & Amundson, D. R. (2002). Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior, 34(4), 224–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60097-3

Lawton, T. (2023). Period Talk. Retrieved from https://www.talkrevolution.com.au/period-talk

Li, A. D., Bellis, E. K., Girling, J. E., Jayasinghe, Y. L., Grover, S. R., Marino, J. L., & Peate, M. (2020). Unmet needs and experiences of adolescent girls with heavy menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea: A qualitative study. Journal of Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology, 33(3), 278–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2019.11.007

Littleton, F. K. (2014). How teen girls think about fertility and the reproductive lifespan. Possible implications for curriculum reform and public health policy. Human Fertility, 17(3). https://doi.org/10.3109/14647273.2014.942389

Liu, X., Liu, Z. Z., Fan, F., & Jia, C. X. (2018). Menarche and menstrual problems are associated with non-suicidal self-injury in adolescent girls. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 21(6), 649–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0861-y

Lundsberg, L. S., Pal, L., Gariepy, A. M., Xu, X., Chu, M. C., & Illuzzi, J. L. (2014). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding conception and fertility: A population-based survey among reproductive-age United States women. Fertility & Sterility, 101(3), 767–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.006

Mackinnon, A. (1995). From on fin de siecle to another: The educated woman and the declining birth-rate. Australian Educational Researcher, 22(3), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03219601

Neergaard, M. A., Olesen, F., Andersen, R. S., & Sondergaard, J. (2009). Qualitative description: The poor cousin of health research? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9(1), 52–52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-52

Nutbeam, D. (2000). Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promotion International, 15(3), 259–267.

Parker, M., Sneddon, A., & Arbon, P. (2010). The menstrual disorder of teenagers (MDOT) study: Determining typical menstrual patterns and menstrual disturbance in a large population-based study of Australian teenagers. BJOG, 117(2), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02407.x

Paynter, M., & Bruce, N. (2013). A futures orientation in the Australian Curriculum: Current levels of teacher interest, activity and support in Western Australia. Australian Educational Researcher, 41(1), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-013-0122-z

Pedro, J., Brandão, T., Schmidt, L., Costa, M. E., & Martins, M. V. (2018). What do people know about fertility? A systematic review on fertility awareness and its associated factors. Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences, 123(2), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/03009734.2018.1480186

Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia. (2023). PPEP Talk®. Retrieved from https://www.pelvicpain.org.au/schools-ppep-program/

Pound, P., Langford, R., & Campbell, R. (2016). What do young people think about their school-based sex and relationship education? A qualitative synthesis of young people's views and experiences. BMJ Open. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011329

Powell, M. A., Graham, A., Fitzgerald, R., Thomas, N., & White, N. E. (2018). Wellbeing in schools: What do students tell us? Australian Educational Researcher, 45(4), 515–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-018-0273-z

Randhawa, A. E., Tufte-Hewett, A. D., Weckesser, A. M., Jones, G. L., & Hewett, F. G. (2021). Secondary school girls’ experiences of menstruation and awareness of endometriosis: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology, 34(5), 643–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2021.01.021

Rosenfield, L. R. (2013). Adolescent anovulation: Maturational mechanisms and implications. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 98(9), 3572–3583. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-1770

Roux, F., Burns, S., Chih, H. J., & Hendriks, J. (2019). Developing and trialling a school-based ovulatory-menstrual health literacy programme for adolescent girls: A quasi-experimental mixed-method protocol. BMJ Open (9:e023582). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023582

Roux, F., Burns, S., Chih, H., & Hendriks, J. (2022). The use of a two-phase online Delphi panel methodology to inform the concurrent development of a school-based ovulatory menstrual health literacy intervention and questionnaire. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, 3, 826805–826805. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2022.826805

Roux, F., Burns, S., Hendriks, J., & Chih, H. J. (2021). Progressing toward adolescents’ ovulatory-menstrual health literacy: A systematic literature review of school-based interventions. Women’s Reproductive Health, 8(2), 92–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/23293691.2021.1901517

Roux, F., Chih, H., Hendriks, J., & Burns, S. (2023). Validation of an ovulatory menstrual health literacy questionnaire. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.13680

Sawyer, S., Raniti, M., & Aston, R. (2021). Making every school a health-promoting school. The Lancet, 5(8), 539–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00190-5

Schmitt, M. L., Hagstrom, C., Nowara, A., Gruer, C., Adenu-Mensah, N. E., Keeley, K., & Sommer, M. (2021). The intersection of menstruation, school and family: Experiences of girls growing up in urban cities in the U.S.A. International Journal of Adolescence & Youth, 26(1), 94–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2020.1867207

School Curriculum & Standards Authority. (2023). Health and Physical Education Curriculum—Pre-Primary to Year 10. Retrieved from https://k10outline.scsa.wa.edu.au/home/p-10-curriculum/curriculum-browser/health-and-physical-education

Stubbs, M. L., & Costos, D. (2004). Negative attitudes toward menstruation: Implications for disconnection within girls and between women. Women & Therapy, 27(3–4), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1300/J015v27n03_04

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

van Iersel, K. C., Kiesner, J., Pastore, M., & Scholte, R. H. J. (2016). The impact of menstrual cycle-related physical symptoms on daily activities and psychological wellness among adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.03.007

Vigil, P., Ceric, F., Cortés, M., & Klaus, H. (2006). Usefulness of monitoring fertility from menarche. Journal of Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology, 19(3), 173–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2006.02.003

Wilding, L., & Griffey, S. (2015). The strength-based approach to educational psychology practice: A critique from social constructionist and systemic perspectives. Educational Psychology in Practice, 31(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2014.981631

Willis, D. G., Sullivan-Bolyai, S., Knafl, K., & Cohen, M. Z. (2016). Distinguishing features and similarities between descriptive phenomenological and qualitative description research. Western Journal of Nursing Ressearch, 38(9), 1185–1204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945916645499

Wister, J., Stubbs, M., & Shipman, C. (2013). Mentioning menstruation: A stereotype threat that diminishes cognition? Sex Roles, 68(1–2), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0156-0

World Health Organization. (2009). 7th Global Conference on Health Promotion, Track 2: Health literacy and health behaviour. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/enhanced-wellbeing/seventh-global-conference/health-literacy.

World Health Organization and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2021). Making every school a health-promoting school. global standards and indicators for health-promoting schools and systems. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025059

Wyn, J. (2007). Learning to “become somebody well” : Challenges for educational policy. Australian Educational Researcher, 34(3), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216864

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship under Grant CHESSN8617438119.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. Funding was provided by Australian Government (Grant No. CHESSN8617438119).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection was performed by FR. Analysis was performed by FR and JH. The first draft of the manuscript was written by FR. All authors reviewed and commented on iterative versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and / or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

Ethics approvals were granted from the Human Research Ethics Committee at Curtin University (HREC 2018-0101-02) and Catholic Education Western Australia (RP2018/44).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roux, F., Burns, S., Hendriks, J. et al. “What’s going on in my body?”: gaps in menstrual health education and face validation of My Vital Cycles®, an ovulatory menstrual health literacy program. Aust. Educ. Res. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-023-00632-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-023-00632-w