Abstract

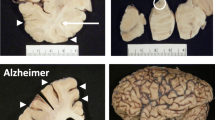

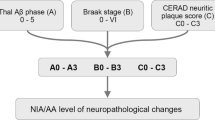

The key pathological hallmarks—extracellular plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFT)—described by Alois Alzheimer in his seminal 1907 article are still central to the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but major advances in our understanding of the underlying pathophysiology as well as significant progress in clinical diagnosis and therapy have changed the perspective and importance of neuropathologic evaluation of the brain. The notion that the pathological processes underlying AD already start decades before symptoms are apparent in patients has brought a major change reflected in the current neuropathological classification of AD neuropathological changes (ADNC). The predictable progression of beta-amyloid (Aβ) plaque pathology from neocortex, over limbic structures, diencephalon, and basal ganglia, to brainstem and cerebellum is captured in phases described by Thal and colleagues. The progression of NFT pathology from the transentorhinal region to the limbic system and ultimately the neocortex is described in stages proposed by Braak and colleagues. The density of neuritic plaque pathology is determined by criteria defined by the Consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s diseases (CERAD). While these changes neuropathologically define AD, it becomes more and more apparent that the majority of patients present with a multitude of additional pathological changes which are possible contributing factors to the clinical presentation and disease progression. The impact of co-existing Lewy body pathology has been well studied, but the importance of more recently described pathologies including limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE), chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), and aging-related tau astrogliopathy (ARTAG) still needs to be evaluated in large cohort studies. In addition, it is apparent that vascular pathology plays an important role in the AD patient population, but a lack of standardized reporting criteria has hampered progress in elucidating the importance of these changes for clinical presentation and disease progression. More recently a key role was ascribed to the immune response to pathological protein aggregates, and it will be important to analyze these changes systematically to better understand the temporal and spatial distribution of the immune response in AD and elucidate their importance for the disease process. Advances in digital pathology and technologies such as single cell sequencing and digital spatial profiling have opened novel avenues for improvement of neuropathological diagnosis and advancing our understanding of underlying molecular processes. Finally, major strides in biomarker-based diagnosis of AD and recent advances in targeted therapeutic approaches may have shifted the perspective but also highlight the continuous importance of postmortem analysis of the brain in neurodegenerative diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

AD is a prime example of how our understanding of neurodegenerative diseases has evolved over time and illustrates the important role postmortem evaluation of the brain plays in elucidating disease mechanisms. Alois Alzheimer’s initial case report connected a clinical dementia syndrome with distinct neuropathological findings [1]. His neuropathological evaluation heavily relied on morphology, conventional staining modalities, and silver staining techniques to detect pathological protein aggregates, which could be classified by their morphologic appearance and localization as extracellular plaques (“drusen”) and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (“neurofibrillen”) [1]. The advent of immunohistochemistry and the identification of Aβ as the central component of plaques [2] and of tau as the main constituent of NFT [3,4,5,6,7,8] has fueled research into the underlying pathophysiology and was central to identifying underlying pathological patterns solidifying early staging schemes. For some time, the main role of neuropathologic evaluation was to confirm or refute a clinical diagnosis of AD. This changed when the current 2012 NIA guidelines for the diagnosis of AD were proposed, which acknowledged by virtue of biomarker studies that the pathophysiological processes underlying AD can start decades before any clinical symptoms appear, thus defining ADNC based on the presence and extent of Aβ plaque and NFT distribution as well as neuritic plaque density [9, 10]. Each of these three pathological hallmarks is scored individually in a three-tiered scoring system (discussed in detail below), and these scores are used to assign a likelihood that the observed changes underlie the clinically observed symptoms. Aside from the AD-defining changes, the recommendations also proposed criteria to report on existing co-pathology and provided guidance on estimating the relative contribution of these changes to the reported clinical symptoms. Subsequently, our understanding of co-pathology in the form of LATE-NC [11], CTE [12], and ARTAG [13] has been further refined and continues to be studied. The contribution of vascular changes and the emerging role of the immune system in the disease process are still understudied, owing to a lack of consensus criteria for neuropathological evaluation. We will provide an overview to current approach to the classification of ADNC and provide a perspective on how novel technologies and experimental studies may transform our understanding of the pathophysiological processes underlying AD.

Beta-Amyloid (Aβ)

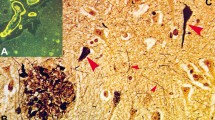

The identification of Aβ as a central component of extracellular plaques [2], as well as genetic evidence linking the amyloid precursor protein (APP) [14, 15] and its processing by beta- [16] and gamma-secretase [17,18,19] to autosomal-dominant forms of AD, has led to the formulation of the amyloid cascade hypothesis [20] which endures as the favored pathophysiological framework to understand AD. Multiple different forms of Aβ deposits can be identified in the AD brain, ranging from diffuse, or “lake-like” amyloid over compact, coarse grained, cotton-wool to cored- or senile plaques (reviewed in [21]) (Fig. 1A, B). The importance of each of these types of Aβ deposits has been studied extensively, and it seems to be more and more evident that diffuse Aβ plaques are probably more benign in nature, as they can be seen in cognitively normal subjects with minimal to no co-existing tau pathology (termed “pathological aging”) [22], while cored plaques, which are often identical to neuritic plaques discussed in detail below, are associated with cognitive decline.

A systematic study by Thal and colleagues showed that Aβ plaques spread through the brain in a predictable fashion, which is summarized in five distinct phases [23]. Early deposits can be seen in the neocortex (phase 1). Subsequently, Aβ plaques appear in limbic regions including entorhinal cortex, subiculum, amygdala, and cingulate gyrus (phase 2). Further progression is characterized by Aβ deposits in subcortical areas including basal ganglia and thalamus (phase 3). In later disease stages, structures of the brainstem including midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata are affected (phase 4), while in end stage cases, Aβ plaques can also be found in the cerebellar cortex (phase 5). Phases 4 and 5 were associated with the presence of dementia, while phases 1 and 2 were mostly seen in asymptomatic individuals [23]. This staging scheme was the basis for the current NIA-Neuropathology criteria to classify amyloid (“A”) pathology. The original phases were condensed into a three-tier staging system, assigning phases 1 and 2 the score A1 (early phases, often seen in asymptomatic individuals), phase 3 the score A2 (intermediate phase), and phases 4 and 5 the score A3 (end stage disease) [9, 10]. While this scoring system provides a solid framework to assess Aβ deposits, it is obvious that the mere distribution of Aβ plaques does not correlate well with the appearance of symptoms, especially in early stages of disease. The notion that Aβ deposits are a complex structure with a multitude of co-aggregating proteins, such as Apolipoprotein E (APOE) [24, 25], Clusterin (APOJ) [26], or Midkine [27] and complex interaction with surrounding cells and cellular processes (reviewed in [28]), may hold the key to refine our understanding of which processes are essential drivers of disease. Better understanding of these complex interactions may guide the identification of novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Aβ does not only form aggregates in the brain parenchyma, but prominent deposits of β-amyloid can also be observed in cerebral and leptomeningeal blood vessels (Fig. 1C). This pathology is termed cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) and is commonly seen in AD cases [29, 30]. The majority of CAA cases are caused by deposition of β-amyloid in the context of ADNC, but rare familial forms of CAA with proteins other than Aβ have been described [31], including cystatin C, gelsolin, prion protein, and transthyretin, among others. The composition of vascular amyloid differs slightly from Αβ plaques, with the latter being driven mostly by longer Aβ species (Aβ1-42) and the former mostly consisting of shorter Aβ species (Aβ1-40) [32,33,34]. An important consequence of vascular Aβ deposition is the destruction of the walls of blood vessels and subsequent likelihood of cerebral hemorrhage, either in the form of microhemorrhages or large lobar hemorrhage [35]. Perivascular drainage pathways likely reflect the major clearance route of Aβ out of the brain and impairment of this process appears to be a major contributing factor to the development of sporadic AD [36]. CAA may also underlie some of the side effects observed with therapeutic strategies targeting Aβ using monoclonal antibodies, resulting in amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), including edema and hemorrhages in a subset of antibody-treated patients [37]. Multiple neuropathological staging schemes for the quantification of CAA have been proposed rating the severity of vascular wall integrity impairment [38], as well as the distribution of CAA throughout the brain [39, 40]. Regardless of which of these criteria are used, it is clear that more severe pathology is associated with more severe consequences such as micro- or macro-hemorrhage or infarcts [38,39,40].

Biomarkers allow monitoring the appearance of Aβ deposits in living patients, and the development of additional biomarkers for tau pathology and neurodegeneration has led to the formulation of the A (amyloid), T (tau), and N (neurodegeneration) definition of AD [41, 42]. A reduction of Aβ1-42 or of the ratio of Aβ1-42/Aβ1-40 is a good indicator of Aβ pathology in the brain and imaging with Aβ amyloid-specific positron emission tomography (PET) ligands can give an impression of the regional distribution of Aβ pathology (reviewed in [43]). Current PET ligands for Aβ show in general a good correlation between in vivo PET signal and postmortem Aβ plaque burden measured at autopsy [44,45,46,47,48]. Taking advantage of these developments, Aβ biomarkers are used a key indicators of target engagement and central outcome measures in current trials to reduce Aβ burden with passive immunotherapy [49,50,51,52], but detailed autopsy studies are still needed to ensure that the biomarkers performance is as accurate as assumed in patients treated with Aβ modifying therapies.

Tau

NFT, the second major pathological finding in AD, are formed by aggregates of the microtubule associated protein tau [3,4,5,6,7,8] (Fig. 2A). In a seminal study, Braak and colleagues studied 83 brains using whole hemisphere 100-μm-thick sections and silver staining techniques to identify a stereotypic pattern of spread of these aggregates [53]. The very first NFT were noted in the transentorhinal region of the hippocampal formation (stage I). From there, the density of aggregates progresses and also involves the subiculum region of the hippocampal pyramidal cell layer (stage II). This early presentation of NFT pathology is referred to as “transentorhinal stages” [53]. As the disease progresses, NFT start to impact the entorhinal cortex and the hippocampal pyramidal cell layer, including sector CA1 (stage III). The changes intensify in these areas, including sectors CA1–CA4 of the hippocampal pyramidal cell layer, and also spread forward into the adjacent inferior temporal cortex. Further spread of NFT pathology is noted in other neocortical areas such as superior temporal cortex and frontal cortex (stage IV). These intermediate stages are often referred to as “limbic stages” [53], as the hippocampal formation is most severely affected. In later phases of the disease, the changes intensify in the hippocampal formation but also affect other areas of the neocortex, including secondary association areas and ultimately primary cortical areas. These late disease stages are therefore called “isocortical stages” [53]. This progression is typically assessed by studying a section of the occipital cortex, where pathology in the peristriate area defines stage V and intraneuronal aggregates in the striate area define stage VI. Similar to the Thal staging scheme for beta-amyloid described above, the NFT stages described here also show some correlation with observed clinical symptoms, as Braak stages V and VI show the strongest association with clinically observed dementia, while stages I and II are encountered not unfrequently in clinically asymptomatic individuals [53]. In light of this correlation with clinical findings, the current NIA staging scheme the six Braak stages were condensed into a 3-tier system with “B1” corresponding to Braak stages I and II, “B2” corresponding to Braak stages III and IV, and “B3” encompassing Braak stages V and VI [9, 10]. While the original NFT staging scheme was derived from studies using whole hemisphere thick sections and silver staining techniques, subsequent studies validated the use of standard, thin (5–8umthick) sections, sampling of select regions, and staining with specific tau antibodies for determining the NFT stages [54, 55].

Redistribution of tau from the axonal compartment to the somato-dentritic compartment and abnormal phosphorylation of tau appears to underlie the formation of NFT [56] and studies using antibodies specific for phosphorylated tau revealed earlier stages of tau aggregation in neurons, so called pre-tangles [57]. This prompted additional systematic studies which identified some of these presumed precursor lesions in neuronal populations of the brain stem, most prominently the locus coeruleus, thus expanding the view of tau pathology in humans with respect to anatomical distribution and age span of affected individuals[57,58,59]. The notion that tau appears to spread between anatomically connected regions has fueled major research efforts identifying a “prion-like” spreading mechanism of tau between connected neuronal populations in animal models and possibly also human subjects suffering from AD [60]. While the exact mechanisms by which tau may spread across synapses to neighboring neurons still require definitive elucidation, insight into this process may prove crucial to the development of disease-modifying therapies. Identification of early lesions in the locus coeruleus has also drawn attention to potential connections to peripheral organs and explorations into possible origins of pathological protein aggregates in enteric neurons (“gut-brain axis”) [61]. This connection appears to be important for other neurodegenerative diseases as well, in particular Parkinson’s disease (PD), where pathological aggregates of alpha-Synuclein (aSyn) have been identified in enteric neurons and peripheral nerves in very early disease stages [62,63,64,65,66].

In a similar fashion to Aβ aggregates (see above), there is appreciable evidence that not all tau inclusions are created equal. Crary and colleagues described early stage (Braak stages I–VI) tau pathology in patients with no significant Aβ deposits, which was—at least with lower Braak stages—not associated with major cognitive impairment. This was termed “primary age-related tauopathy” (PART) [67]. The observed tau inclusions in PART appear similar to NFT seen in AD, with respect to histological appearance and tau isoform composition [67], but subsequent studies identified subtle differences in the distribution of NFT, with the CA2 region of the hippocampal pyramidal cell layer being more severely affected in PART as compared to AD [68, 69]. The largely innocuous nature of NFT in PART stands in stark contrast to other tau associated pathologies in frontotemporal dementia (FTLD) with tau pathology, such as Pick’s disease, corticobasal degeneration (CBD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), and globular glial tauopathy (GGT) (reviewed in [70]), wherein tau aggregation appears to be the major driver of neurodegeneration and symptom onset. The identification of PART underscores once more the importance of the co-occurrence of Aβ deposits and NFT pathology in the pathophysiology of AD, as neither Aβ plaques (pathological aging) [22] nor NFT (PART) [12] in isolation are associated with major neuronal loss and cognitive impairment [71]. This notion underscores the importance of identifying the “synergistic” link between Aβ and tau pathology to fully understand the pathologic genesis of AD.

Biomarkers for tau pathology play a key role in the proposed A/T/N system described above [41, 42]. Multiple different phosphorylated epitopes in tau (p-tau) have been identified in histopathologic lesions and detection of these p-tau species in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and blood serves as a good peripheral surrogate for the presence of tau pathology in the brain (reviewed in [72]). Studies with tau PET ligands correlate with the model of a stage-wise progression of tau pathology in the brain of AD patients described above [73, 74], but issues with “off-target” binding in certain brain regions, as well as distinction of AD from other neurodegenerative tauopathies, still need to be worked out [75,76,77].

Neuritic Plaques

A potential key to understanding the interaction of Aβ and tau may lie with a specific type of plaque: the neuritic plaque, sometimes also referred to as senile plaque [22, 78] (Fig. 2B). Dystrophic neurites were long known to be associated with Aβ deposits, and detailed descriptions highlight entrapment of cellular organelles, such as lysosomes and lysosomal proteins, as well as aggregated forms of tau in these structures [79]. Many markers and techniques can be used to identify neuritic plaques, including silver staining, tau antibodies, antibodies against lysosomal proteins (LAMP1, Cathepsin D), or other axonally transported neuronal proteins (APP, BACE1) [80,81,82,83,84]. Early studies used the classic amyloid dye thioflavin to identify neuritic plaques, as these are most often identical to so called “cored plaques” which are characterized by a dense amyloid core and a more diffuse halo. The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD) published a staging scheme using thioflavin staining (or silver staining) to quantify the density in multiple neocortical areas in a 10 × microscopic field as sparse, moderate or frequent [78]. Correlated with the age of the subject, the density of neuritic plaques showed some correlation with symptoms of dementia; sparse neuritic plaques in an individual over 75 years of age were considered uncertain evidence of AD, while frequent plaques in younger individuals were considered to indicate a diagnosis of AD [78]. The algorithm to quantify neuritic plaques proposed by the CERAD consortium was adopted by the current NIA criteria to assign a “CERAD score,” with sparse neuritic plaque pathology being assigned a score of “C1,” moderate density “C2,” and frequent neuritic plaques “C3” [9, 10]. The association with age was not adopted for the new criteria, which instead assign a likelihood for the observed changes to be underlying observed cognitive symptoms based on the co-occurrence of amyloid (A), NFT pathology (B), and neuritic plaques (C, see below) [9, 10]. The current NIA criteria emphasize the importance of identifying only plaques surrounded by dystrophic neurites as “neuritic” and recommend the use of thioflavin or silver staining techniques for this assessment [10]. Multiple immunohistochemical markers for dystrophic neurites, including amyloid precursor protein, ubiquitin, neurofilament, and phospho-tau, have been demonstrated to label dystrophic neurites, but these may only label specific subtypes of neuritic plaques with varying disease relevance [80]. A specific case can however be made for the use of phospho-tau as a marker for neuritic plaques, as increased tau phosphorylation was noted around neuritic plaques in carriers of AD risk associated variants in the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM) 2 [71, 85]. Furthermore, recent studies in animal models highlight the importance of Aβ deposit associated tau positive dystrophic neurites for the subsequent spread of neuronal tau pathology [86] supporting the notion that this specific type of plaque may represent a key interface between Aβ and tau pathology in AD and may serve as a window to understand the pathophysiological cascade of AD.

Immunohistochemical stain with anti-Aβ antibody Ab5 [159] showing a diffuse Aβ plaque in inferior temporal cortex (A), a cored Aβ plaque in the frontal cortex (B), and CAA affecting leptomeningeal blood vessels overlying the frontal cortex (C). Scale bar = 10 μm, shown in (C)

ABC Scoring of ADNC

The current NIA criteria for staging of ADNC provide a framework to quantify the progression of Aβ pathology (Amyloid score, Thal phases), NFT pathology (Braak score, Braak stages), and neuritic plaque pathology (CERAD score). Based on combination of these “ABC” scores, the severity of ADNC is quantified as “not,” “low,” “intermediate,” and “high” [10]. There is a very good correlation between high ADNC scores and the presence of clinically observed dementia, while this correlation becomes less tight with intermediate and lower ADNC scores. Vice versa, high and intermediate ADNC scores are considered a sufficient explanation for clinically observed cognitive impairment, while lower scores make and alternative explanation more likely [10]. Regardless of the level of ADNC, the current NIA criteria suggest careful documentation of all co-existing pathologies, as there are no absolute thresholds for any given pathology that are invariably associated with symptom onset or severity [87]. Especially in individuals with no obvious clinical symptoms, additional factors such as cognitive reserve and resilience are hard to quantify through neuropathological examination.

The above staging criteria outline the progression of pathological changes in AD, but not all cases of AD follow this stage-wise progression. Multiple subtypes of AD have been described in a clinic-pathologic study based on progression and affected regions [88], and recently even more subtypes of AD have been proposed using artificial intelligence based analysis of tau imaging modalities [89]. While it is important to be aware of this heterogeneity of AD with potentially multiple subtypes, it is nevertheless of utmost importance to quantify the pathological findings in a standardized fashion to allow clinic-pathological association studies in large multi-institutional cohorts.

Another very important factor is the occurrence of pathology other than Aβ and tau, which can be observed in the brains of these elderly subjects. Studies of large autopsy cohorts and data from our own brain bank highlight the fact that “pure” AD with only Aβ and NFT pathology is rare, and co-pathology in the form of Lewy body pathology, other protein aggregates, and vascular pathology is in fact very common and contributing to the overall clinical presentation of each individual case [90,91,92,93,94,95,96]. The appearance of aggregates of multiple proteins may reflect a state of brain “organ failure” in later stages of disease, where defense mechanisms are impaired and multiple pathologies appear to progress.

In the following, we will provide an overview of prominent co-pathology observed in AD brains and discuss the relevance of these findings for the overall interpretation of the case.

Lewy Body Pathology

Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites (collectively referred to as Lewy body disease (LBD) in the following) (Fig. 3A) consist of pathological aggregates of aSyn and are the major pathological hallmark of PD and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) [97,98,99,100]. Similar to tau aggregates in NFT, these pathological inclusions appear to spread through the brain in a stage-like fashion starting in the lower brain stem with the dorsal motor nucleus of vagus and ascending through pons and midbrain before reaching limbic structures and finally also the neocortex [63, 101, 102]. Connections of lower brain stem nuclei and peripheral neuronal population, specifically enteric neurons, as well as evidence from experimental animal studies highlight the importance of a cross talk between the CNS and the periphery and have fueled research endeavors studying the gut-brain axis in PD and DLB [62, 63, 103]. In addition to early deposits in neuronal populations, the olfactory bulb appears to be affected early in the progression of LBD, inspiring theories of a potential airborne component to the disease [63, 101]. The spread of LBD pathology throughout the brain has been described by Braak and colleagues in six stages, where the midbrain is affected in stage 3, which also most often coincides with symptom onset in PD [101]. Multiple prominent scoring systems for LBD pathology have emerged subsequently. The majority of these adopted a 4-tier semiquantitative scoring approach to quantify the severity of LBD in multiple brain regions into mild, moderate, severe, and very severe, as initially proposed by McKeith et al. [98, 104]. The first iteration of this scoring system described three major patterns of LBD pathology, which follow the stage-wise spread described by Braak and colleagues [101]. In the brainstem-predominant type, LBD pathology is mainly observed in medulla, pons, and midbrain. Further spread to limbic structures including hippocampus, amygdala, and cingulate gyrus defines the limbic transitional type. The presence of disease in neocortical areas defines the diffuse neocortical type [104]. However, a major shortcoming of this scoring algorithm is the omission of at least one additional type of Lewy body pathology often detected in AD, the amygdala-predominant LBD, sometimes also described as amygdala type of AD [105,106,107]. Updated scoring systems have therefore broadened the patterns of LBD pathology to also include the amygdala predominant type, as well as cases which only show LBD pathology in the olfactory bulb [98, 108, 109]. While these improvements significantly reduced the number of “unclassifiable” cases, the semiquantitative scoring of LBD pathology still sometimes resulted in poor interrater reliability. A recently proposed scoring system addressed this issue by adopting a simple positive/negative assessment of aSyn pathology to assign the five patterns of LBD pathology [110]. The NIA criteria for diagnosis of ADNC were formulated, while the debates about scoring were still ongoing and recommend to use the semiquantitative approach proposed by McKeith in 2005 [104] with modifications to also include the amygdala predominant subtype and suggest to classify LBD pathology into none, brainstem predominant, limbic (transitional), neocortical (diffuse), and amygdala predominant [10].

LBD is the most common co-pathology in AD and can contribute in a major fashion to the observed clinical presentation [90], although the gender distribution is distinct between LBD and AD. Vice versa, ADNC are often associated with cognitive decline in late-stage PD [111], termed Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) [112, 113], and are a prominent type of co-pathology in DLB [10, 90, 98]. Given the frequent co-occurrence of LBD and ADNC, the distinction between DLB and AD is often not possible based on neuropathological examination alone but requires careful integration of clinical data including age of onset for motor symptoms and cognitive decline, as well as other prominent symptoms such as REM sleep disorders or hallucinations [98]. The quantification of the severity of AD-related pathology following the NIA criteria [9, 10] and LBD following McKeith et al. [98] can aid this differential diagnosis to extrapolate the relative contribution of different types of pathology. Association of severe LBD with marked loss of dopaminergic neurons may be an important clue tipping the scale towards DLB versus AD in the overall assessment[67, 98].

Limbic-Predominant Age-Related TDP-43 Encephalopathy (LATE)

In 2006, TDP-43 was identified as the main component of pathological aggregates in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and a major subtype of FTLD, as well as overlap syndromes between the two [114]. Using specific antibodies, aggregates of TDP-43 have been documented in aged subjects without obvious history of motor neuron disease and FTLD [11, 115] (Fig. 3B). In some cases, this TDP-43 pathology is associated with neuron loss in some sectors of the hippocampal pyramidal cell layer (hippocampal sclerosis) [116]. Multiple groups investigated age-related TDP-43 pathology, assigning multiple names and proposing different staging schemes [11, 117, 118]. A recent multi-institutional effort consolidated these efforts and put forward the widely used term of LATE and proposed three distinct stages for classification of LATE-neuropathological change (NC) [11]. Stage 1 only affects the amygdala. Stage 2 affects the amygdala and the hippocampus, in particular the hippocampal pyramidal cell layer. Stage 3 incorporates involvement of the neocortex, with the frontal cortex proposed as the key section to be studied in neuropathological studies. Hippocampal sclerosis is scored in addition to the described stages [11]. LATE-NC is present in up to 60% of AD cases and is associated with a faster rate of cognitive decline and hippocampal atrophy [162,163,164]. Observations that LATE-NC is associated with memory impairment in the elderly, even in the absence of significant ADNC or FTLD-TDP pathology (164, 165), further underscore the importance of recognizing and reporting this type of pathology. Underlying TDP-43 pathology may be an important confounding factor when assessing the efficacy of Aβ or tau targeting therapies currently in clinical trials, as there are no imaging markers and biomarkers to reliably predict the extent of LATE-NC in AD patients to date. Autopsy studies in patients participating in clinical trials will hopefully shed light on this issue, specifically in patients who showed response in Aβ- and/or tau-related biomarkers, but no improvement of cognitive decline.

Glial Tau Pathology

Pathological inclusions of tau in glial cells are major hallmarks of subtypes of FTLD-tau, including PSP (tufted astrocytes), CBD (astrocytic plaques), and GGT (globular glial inclusions). Distinct astroglial tau inclusions mainly in the form of thorn-shaped astrocytes and granular fuzzy astrocytes can also be observed in other neurodegenerative conditions [70, 119], most prominently in chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and aging-related astroglial tauopathy (ARTAG). Neuronal tau aggregates in specific anatomic locations such as the depth of sulci and perivascular distributions, with or without the co-occurrence of astroglial tau inclusions, mainly in the form of thorn-shaped astrocytes, are required for the neuropathological diagnosis of CTE, a condition associated with severe, repetitive head trauma [12, 120]. CTE can be observed in athletes involved in contact sports such as football, boxing, or hockey but can also be seen in soldiers exposed to blast injury [12, 121]. While the characteristic tau inclusions associated with CTE can be the major neuropathologic change underlying observed clinical symptoms, in particular in younger subjects, CTE-related tau pathology can also be observed as a co-pathology in older subjects suffering from AD [122]. Systematic studies in large autopsy cohorts will be required to accurately assess the contribution of CTE to observed symptoms in AD, but recently refined standardized diagnostic criteria for CTE neuropathological changes [12] are an important step to systematically quantify and analyze these changes during the neuropathological workup of cases.

In ARTAG, astroglial tau inclusions in the form of thorn-shaped astrocytes and granular fuzzy astrocytes (similar to those described in CTE) are seen in periventricular areas of the medial temporal lobe and subpial areas without significant associated neuronal inclusions [13]. The clinical relevance of ARTAG in the context of AD and other neurodegenerative diseases, as well as of ARTAG as a stand-alone pathology, still needs to be determined in systematic large cohort studies, but recently proposed standardized reporting criteria [13, 123] are an important first step towards identifying the importance of this type of pathology for AD.

Vascular Pathology

Vascular disease is widely acknowledged as an important risk factor for the development of AD and dementia [124]. Vascular pathology in the form of macro- or microinfarction, diffuse white matter degeneration, micro- and macrohemorrhage, atherosclerosis, and arteriolosclerosis is frequently observed in brain autopsies of elderly individuals, in particular in patients suffering from neurodegenerative disease [125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135]. Small vessel cerebrovascular disease-like changes with arterial hyalinization and widened perivascular spaces, sometimes containing hemosiderin, may occur with advanced aging and such changes are typically found in lenticulostriate branches of the middle cerebral artery. A subset of small vessel cerebrovascular disease that affects cerebral arterioles in the elderly has been described under the term brain arteriolosclerosis (B-ASC) [115]. B-ASC can be seen in a substantial proportion of older individuals, is associated with decreased cognition, and may be linked to certain genetic variants [135].

The current NIA criteria encourage detailed reporting of vascular lesions in AD cases, but estimating the contribution of these changes to the observed clinical presentation is still very enigmatic [9, 10]. There are several reasons underlying this obvious issue. Despite novel developments described above, assessment of vascular pathology still remains subjective, as no widely accepted standardized reporting and scoring criteria exist. Accurate assessment of the contribution of vascular pathology to neurodegeneration is limited by the overall composite and complex nature of correlating lifetime risk factors to dementia [87]. The individual threshold as to when an individual will be symptomatic is determined by an intricate interplay of cognitive reserve, resilience, neuronal plasticity, and co-pathology. Although much more research efforts are required to fully understand this very important contributing factor to cognitive decline in an aging population, systematic reporting of vascular pathology as required by the current NIA criteria is an important first step.

ADNC as a Secondary Diagnosis

Since ADNC is very common in the aging population, it is not surprising that Aβ pathology and/or NFT pathology can be observed in other neurodegenerative diseases [90]. As detailed above for the differential diagnosis between AD and DLB, the standardized quantification of pathological findings is key to assess the relative contribution of the respective pathology to the observed clinical syndrome.

Genetic Risk Factors

Mutations in APP and in genes important for APP processing are the cause of early-onset familial forms of AD, and multiple genetic risk factors for the development of sporadic, late-onset AD have been identified (reviewed in [136]). The most prominent of these risk factors is the Apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene, wherein the presence of the epsilon 4 allele is associated with a significantly increased risk to develop AD [137].

Refined techniques and analysis of larger patient cohorts have aided the identification of multiple additional AD risk factors, the majority of which are in genes associated with immune functions. Most saliently with respect to increased risk, the TREM2 gene has been identified as important for microglia and macrophage function (reviewed in [138]). In particular, this obvious strong genetic connection between the immune system and the risk to develop AD has spurred massive research efforts into the role of immune cells and immune molecules in AD and has broadened our view of the pathophysiological cascade in AD, leading to the integration of a “cellular phase” in a revised version of the amyloid cascade hypothesis, where pathological processes instigated by pathological protein aggregates are amplified by immune responses directed towards them [28]. Given the obvious importance of immune processes in the pathophysiology of AD, it will be important to establish standardized reporting criteria for processes such as astrogliosis and microglia activation to aid further studies into this matter. This will however be a complex process, as microglia and astrocyte show high plasticity resulting in multiple disease-associated phenotypes defined by cellular morphology and genetic signatures (reviewed in [139,140,141]). While there are some pathological clues, including “cotton-wool plaques” predicting certain forms of familial AD [142], specific pathological findings predicting the status of certain genetic risk variant are still missing. Some evidence exists however that genetic risk variants may underlie the observed subtypes of AD described above. Given the observed heterogeneity of AD, the results of recent clinical trials into Aβ-targeting therapies, and other novel therapeutic approaches targeting the immune system, it will be important to take genetic findings into account when assessing brains at autopsy [143]. While an integrated diagnosis including morphological and genetic findings as a basis for targeted therapies is now standard practice in reporting for brain tumors [144, 145], it will have to be determined if future efforts into developing personalized therapeutic interventions for AD will warrant a similar approach.

Novel Developments

Neuropathological examination served as a foundational tool in the first days of establishing a definition of AD. Novel technologies such as immunohistochemistry and genetic analysis have aided the evolution of our current understanding of the pathophysiological processes underlying the disease. Microscopic analysis of glass slides has long been the gold standard for pathological analysis, but recent advancements in whole slide imaging and image analysis have opened up the new field of digital pathology [146, 147]. This has enabled exploits into artificial intelligence assisted analysis of various aspects of neurodegenerative diseases and aides in sharing of digital slides across multiple institutions for teaching and research [13, 148,149,150]. Emergence, refinement, and widespread accessibility of new technologies including single cell sequencing, proteomics, multiplexed immunohistochemistry, and spatial analysis of RNA and proteins in situ have expanded the available toolkit to unravel disease mechanisms by studying postmortem human brains [71, 151,152,153,154,155]. Once our understanding of the basic pathophysiologic mechanisms of AD reaches sufficient maturation, some anticipate that the definition of AD will shift from the current amalgam of ADNC and syndromal description, to an increasingly biological construct that fully integrates premortem biomarkers along with traditional postmortem proteinopathy and premortem symptomatology [42].

Conclusion

Initial autopsy findings laid the groundwork for defining AD [1], and neuropathological studies were key in understanding the role of Aβ and tau in disease pathogenesis and progression. This informed a biomarker-based approach for the diagnosis of preclinical stages of AD [156], which is central to current efforts to develop disease-modifying therapeutic interventions. Severe side effects of early strategies for active vaccination against Aβ were revealed by neuropathological analysis [157]. Developments in the passive vaccination space—including the hotly debated approval of aducanumab [158]—as well as reports on trials of monoclonal antibodies in cohorts of dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease [51]—further underscore the importance of systematic postmortem analysis for diagnosis and evaluation of therapeutic efficacy.

References

A. A. Über eine eigenartige Erkrankung der Hirnrinde. Allg Z Psychiat Psych-Gericht Med. 1907;64:146–8.

Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer’s disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;120(3):885-90.

Wood JG, Mirra SS, Pollock NJ, Binder LI. Neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer disease share antigenic determinants with the axonal microtubule-associated protein tau (tau). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(11):4040-3.

Kosik KS, Joachim CL, Selkoe DJ. Microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) is a major antigenic component of paired helical filaments in Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(11):4044-8.

Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Quinlan M, Tung YC, Zaidi MS, Wisniewski HM. Microtubule-associated protein tau. A component of Alzheimer paired helical filaments. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(13):6084–9.

Yen SH, Dickson DW, Crowe A, Butler M, Shelanski ML. Alzheimer’s neurofibrillary tangles contain unique epitopes and epitopes in common with the heat-stable microtubule associated proteins tau and MAP2. Am J Pathol. 1987;126(1):81-91.

Nukina N, Ihara Y. One of the antigenic determinants of paired helical filaments is related to tau protein. J Biochem. 1986;99(5):1541-4.

Delacourte A, Defossez A. Alzheimer’s disease: Tau proteins, the promoting factors of microtubule assembly, are major components of paired helical filaments. J Neurol Sci. 1986;76(2-3):173-86.

Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(1):1-11.

Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Carrillo MC, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(1):1-13.

Nelson PT, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, Jack CR, Boyle PA, Arfanakis K, et al. Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE): consensus working group report. Brain. 2019;142(6):1503-27.

Bieniek KF, Cairns NJ, Crary JF, Dickson DW, Folkerth RD, Keene CD, et al. The Second NINDS/NIBIB Consensus Meeting to Define Neuropathological Criteria for the Diagnosis of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2021;80(3):210-9.

Kovacs GG, Xie SX, Lee EB, Robinson JL, Caswell C, Irwin DJ, et al. Multisite Assessment of Aging-Related Tau Astrogliopathy (ARTAG). J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2017;76(7):605-19.

Chartier-Harlin MC, Crawford F, Houlden H, Warren A, Hughes D, Fidani L, et al. Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease caused by mutations at codon 717 of the beta-amyloid precursor protein gene. Nature. 1991;353(6347):844-6.

Goate A, Chartier-Harlin MC, Mullan M, Brown J, Crawford F, Fidani L, et al. Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1991;349(6311):704-6.

Citron M, Oltersdorf T, Haass C, McConlogue L, Hung AY, Seubert P, et al. Mutation of the beta-amyloid precursor protein in familial Alzheimer’s disease increases beta-protein production. Nature. 1992;360(6405):672-4.

Rogaev EI, Sherrington R, Rogaeva EA, Levesque G, Ikeda M, Liang Y, et al. Familial Alzheimer’s disease in kindreds with missense mutations in a gene on chromosome 1 related to the Alzheimer's disease type 3 gene. Nature. 1995;376(6543):775-8.

Sherrington R, Rogaev EI, Liang Y, Rogaeva EA, Levesque G, Ikeda M, et al. Cloning of a gene bearing missense mutations in early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1995;375(6534):754-60.

Levy-Lahad E, Wasco W, Poorkaj P, Romano DM, Oshima J, Pettingell WH, et al. Candidate gene for the chromosome 1 familial Alzheimer’s disease locus. Science. 1995;269(5226):973-7.

Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297(5580):353-6.

Walker LC. Abeta Plaques. Free Neuropathology. 2020.

Dickson DW, Crystal HA, Mattiace LA, Masur DM, Blau AD, Davies P, et al. Identification of normal and pathological aging in prospectively studied nondemented elderly humans. Neurobiol Aging. 1992;13(1):179-89.

Thal DR, Rüb U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology. 2002;58(12):1791-800.

Styren SD, Kamboh MI, DeKosky ST. Expression of differential immune factors in temporal cortex and cerebellum: the role of alpha-1-antichymotrypsin, apolipoprotein E, and reactive glia in the progression of Alzheimer's disease. J Comp Neurol. 1998;396(4):511-20.

Namba Y, Tomonaga M, Kawasaki H, Otomo E, Ikeda K. Apolipoprotein E immunoreactivity in cerebral amyloid deposits and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease and kuru plaque amyloid in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain Res. 1991;541(1):163-6.

Martin-Rehrmann MD, Hoe HS, Capuani EM, Rebeck GW. Association of apolipoprotein J-positive beta-amyloid plaques with dystrophic neurites in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurotox Res. 2005;7(3):231-42.

Yasuhara O, Muramatsu H, Kim SU, Muramatsu T, Maruta H, McGeer PL. Midkine, a novel neurotrophic factor, is present in senile plaques of Alzheimer disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;192(1):246-51.

De Strooper B, Karran E. The Cellular Phase of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell. 2016;164(4):603-15.

Bergeron C, Ranalli PJ, Miceli PN. Amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Can J Neurol Sci. 1987;14(4):564-9.

Jellinger KA, Lauda F, Attems J. Sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy is not a frequent cause of spontaneous brain hemorrhage. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(8):923-8.

Revesz T, Holton JL, Lashley T, Plant G, Rostagno A, Ghiso J, et al. Sporadic and familial cerebral amyloid angiopathies. Brain Pathol. 2002;12(3):343-57.

Prelli F, Castaño E, Glenner GG, Frangione B. Differences between vascular and plaque core amyloid in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 1988;51(2):648-51.

Joachim CL, Duffy LK, Morris JH, Selkoe DJ. Protein chemical and immunocytochemical studies of meningovascular beta-amyloid protein in Alzheimer’s disease and normal aging. Brain Res. 1988;474(1):100-11.

Gravina SA, Ho L, Eckman CB, Long KE, Otvos L, Younkin LH, et al. Amyloid beta protein (A beta) in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Biochemical and immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies specific for forms ending at A beta 40 or A beta 42(43). J Biol Chem. 1995;270(13):7013–6.

McCarron MO, Nicoll JA. High frequency of apolipoprotein E epsilon 2 allele is specific for patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related haemorrhage. Neurosci Lett. 1998;247(1):45-8.

Greenberg SM, Bacskai BJ, Hernandez-Guillamon M, Pruzin J, Sperling R, van Veluw SJ. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and Alzheimer disease - one peptide, two pathways. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16(1):30-42.

Sperling RA, Jack CR, Black SE, Frosch MP, Greenberg SM, Hyman BT, et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in amyloid-modifying therapeutic trials: recommendations from the Alzheimer’s Association Research Roundtable Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(4):367-85.

Vonsattel JP, Myers RH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Ropper AH, Bird ED, Richardson EP. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy without and with cerebral hemorrhages: a comparative histological study. Ann Neurol. 1991;30(5):637-49.

Thal DR, Papassotiropoulos A, Saido TC, Griffin WS, Mrak RE, Kölsch H, et al. Capillary cerebral amyloid angiopathy identifies a distinct APOE epsilon4-associated subtype of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120(2):169-83.

Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Rüb U, Yamaguchi H, Del Tredici K, Braak H. Two types of sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61(3):282-93.

Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Feldman HH, Frisoni GB, et al. A/T/N: An unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology. 2016;87(5):539-47.

Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(4):535-62.

Hampel H, Hardy J, Blennow K, Chen C, Perry G, Kim SH, et al. The Amyloid-β Pathway in Alzheimer's Disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2021.

Choi SR, Schneider JA, Bennett DA, Beach TG, Bedell BJ, Zehntner SP, et al. Correlation of amyloid PET ligand florbetapir F 18 binding with Aβ aggregation and neuritic plaque deposition in postmortem brain tissue. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26(1):8-16.

Sabbagh MN, Fleisher A, Chen K, Rogers J, Berk C, Reiman E, et al. Positron emission tomography and neuropathologic estimates of fibrillar amyloid-β in a patient with Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(11):1461-6.

Clark CM, Pontecorvo MJ, Beach TG, Bedell BJ, Coleman RE, Doraiswamy PM, et al. Cerebral PET with florbetapir compared with neuropathology at autopsy for detection of neuritic amyloid-β plaques: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(8):669-78.

Curtis C, Gamez JE, Singh U, Sadowsky CH, Villena T, Sabbagh MN, et al. Phase 3 trial of flutemetamol labeled with radioactive fluorine 18 imaging and neuritic plaque density. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(3):287-94.

Sabri O, Sabbagh MN, Seibyl J, Barthel H, Akatsu H, Ouchi Y, et al. Florbetaben PET imaging to detect amyloid beta plaques in Alzheimer’s disease: phase 3 study. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(8):964-74.

Mintun MA, Lo AC, Duggan Evans C, Wessels AM, Ardayfio PA, Andersen SW, et al. Donanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(18):1691-704.

Salloway S, Honigberg LA, Cho W, Ward M, Friesenhahn M, Brunstein F, et al. Amyloid positron emission tomography and cerebrospinal fluid results from a crenezumab anti-amyloid-beta antibody double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase II study in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease (BLAZE). Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):96.

Salloway S, Farlow M, McDade E, Clifford DB, Wang G, Llibre-Guerra JJ, et al. A trial of gantenerumab or solanezumab in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2021;27(7):1187-96.

Sevigny J, Chiao P, Bussière T, Weinreb PH, Williams L, Maier M, et al. The antibody aducanumab reduces Aβ plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2016;537(7618):50-6.

Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239-59.

Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112(4):389-404.

Alafuzoff I, Parkkinen L, Al-Sarraj S, Arzberger T, Bell J, Bodi I, et al. Assessment of alpha-synuclein pathology: a study of the BrainNet Europe Consortium. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67(2):125-43.

Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. Biochemistry and cell biology of tau protein in neurofibrillary degeneration. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(7):a006247.

Braak H, Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Del Tredici K. Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: age categories from 1 to 100 years. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;70(11):960-9.

Stratmann K, Heinsen H, Korf HW, Del Turco D, Ghebremedhin E, Seidel K, et al. Precortical Phase of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)-Related Tau Cytoskeletal Pathology. Brain Pathol. 2016;26(3):371-86.

Ehrenberg AJ, Nguy AK, Theofilas P, Dunlop S, Suemoto CK, Di Lorenzo Alho AT, et al. Quantifying the accretion of hyperphosphorylated tau in the locus coeruleus and dorsal raphe nucleus: the pathological building blocks of early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2017;43(5):393-408.

Dujardin S, Hyman BT. Tau Prion-Like Propagation: State of the Art and Current Challenges. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1184:305-25.

Kowalski K, Mulak A. Brain-Gut-Microbiota Axis in Alzheimer's Disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;25(1):48-60.

Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, Shill HA, Driver-Dunckley E, Mehta SH, et al. Vagus Nerve and Stomach Synucleinopathy in Parkinson Disease, Incidental Lewy Body Disease and Normal Elderly Subjects: Evidence Against the Body-First Hypothesis. medRxiv. 2020:2020.09.29.20204248.

Braak H, Rüb U, Gai WP, Del Tredici K. Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: possible routes by which vulnerable neuronal types may be subject to neuroinvasion by an unknown pathogen. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2003;110(5):517-36.

Hilton D, Stephens M, Kirk L, Edwards P, Potter R, Zajicek J, et al. Accumulation of α-synuclein in the bowel of patients in the pre-clinical phase of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(2):235-41.

Shannon KM, Keshavarzian A, Dodiya HB, Jakate S, Kordower JH. Is alpha-synuclein in the colon a biomarker for premotor Parkinson’s disease? Evidence from 3 cases. Mov Disord. 2012;27(6):716-9.

Stokholm MG, Danielsen EH, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Borghammer P. Pathological α-synuclein in gastrointestinal tissues from prodromal Parkinson disease patients. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(6):940-9.

Crary JF, Trojanowski JQ, Schneider JA, Abisambra JF, Abner EL, Alafuzoff I, et al. Primary age-related tauopathy (PART): a common pathology associated with human aging. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128(6):755-66.

Walker JM, Fudym Y, Farrell K, Iida MA, Bieniek KF, Seshadri S, et al. Asymmetry of Hippocampal Tau Pathology in Primary Age-Related Tauopathy and Alzheimer Disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2021;80(5):436-45.

Walker JM, Richardson TE, Farrell K, Iida MA, Foong C, Shang P, et al. Early Selective Vulnerability of the CA2 Hippocampal Subfield in Primary Age-Related Tauopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2021;80(2):102-11.

Kovacs GG. Tauopathies. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017;145:355-68.

Prokop S, Miller KR, Labra SR, Pitkin RM, Hoxha K, Narasimhan S, et al. Impact of TREM2 risk variants on brain region-specific immune activation and plaque microenvironment in Alzheimer’s disease patient brain samples. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;138(4):613-30.

Xia Y, Prokop S, Giasson BI. “Don’t Phos Over Tau”: recent developments in clinical biomarkers and therapies targeting tau phosphorylation in Alzheimer's disease and other tauopathies. Mol Neurodegener. 2021;16(1):37.

Baek MS, Cho H, Lee HS, Choi JY, Lee JH, Ryu YH, et al. Temporal trajectories of in vivo tau and amyloid-β accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47(12):2879-86.

Cho H, Choi JY, Lee HS, Lee JH, Ryu YH, Lee MS, et al. Progressive Tau Accumulation in Alzheimer Disease: 2-Year Follow-up Study. J Nucl Med. 2019;60(11):1611-21.

Leuzy A, Chiotis K, Lemoine L, Gillberg PG, Almkvist O, Rodriguez-Vieitez E, et al. Tau PET imaging in neurodegenerative tauopathies-still a challenge. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(8):1112-34.

Bischof GN, Endepols H, van Eimeren T, Drzezga A. Tau-imaging in neurodegeneration. Methods. 2017;130:114-23.

Okamura N, Harada R, Ishiki A, Kikuchi A, Nakamura T, Kudo Y. The development and validation of tau PET tracers: current status and future directions. Clin Transl Imaging. 2018;6(4):305-16.

Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1991;41(4):479–86.

Gonatas NK, Anderson W, Evangelista I. The contribution of altered synapses in the senile plaque: an electron microscopic study in Alzheimer’s dementia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1967;26(1):25-39.

Dickson TC, King CE, McCormack GH, Vickers JC. Neurochemical diversity of dystrophic neurites in the early and late stages of Alzheimer's disease. Exp Neurol. 1999;156(1):100-10.

Vickers JC, Chin D, Edwards AM, Sampson V, Harper C, Morrison J. Dystrophic neurite formation associated with age-related beta amyloid deposition in the neocortex: clues to the genesis of neurofibrillary pathology. Exp Neurol. 1996;141(1):1-11.

Masliah E, Mallory M, Hansen L, Alford M, DeTeresa R, Terry R. An antibody against phosphorylated neurofilaments identifies a subset of damaged association axons in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1993;142(3):871-82.

Sharoar MG, Palko S, Ge Y, Saido TC, Yan R. Accumulation of saposin in dystrophic neurites is linked to impaired lysosomal functions in Alzheimer’s disease brains. Mol Neurodegener. 2021;16(1):45.

Sadleir KR, Kandalepas PC, Buggia-Prévot V, Nicholson DA, Thinakaran G, Vassar R. Presynaptic dystrophic neurites surrounding amyloid plaques are sites of microtubule disruption, BACE1 elevation, and increased Aβ generation in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132(2):235-56.

Yuan P, Condello C, Keene CD, Wang Y, Bird TD, Paul SM, et al. TREM2 Haplodeficiency in Mice and Humans Impairs the Microglia Barrier Function Leading to Decreased Amyloid Compaction and Severe Axonal Dystrophy. Neuron. 2016;92(1):252-64.

He Z, Guo JL, McBride JD, Narasimhan S, Kim H, Changolkar L, et al. Amyloid-β plaques enhance Alzheimer's brain tau-seeded pathologies by facilitating neuritic plaque tau aggregation. Nat Med. 2018;24(1):29-38.

Nelson PT, Alafuzoff I, Bigio EH, Bouras C, Braak H, Cairns NJ, et al. Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71(5):362-81.

Murray ME, Graff-Radford NR, Ross OA, Petersen RC, Duara R, Dickson DW. Neuropathologically defined subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease with distinct clinical characteristics: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(9):785-96.

Vogel JW, Young AL, Oxtoby NP, Smith R, Ossenkoppele R, Strandberg OT, et al. Four distinct trajectories of tau deposition identified in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2021;27(5):871-81.

Robinson JL, Lee EB, Xie SX, Rennert L, Suh E, Bredenberg C, et al. Neurodegenerative disease concomitant proteinopathies are prevalent, age-related and APOE4-associated. Brain. 2018;141(7):2181-93.

Kovacs GG, Milenkovic I, Wöhrer A, Höftberger R, Gelpi E, Haberler C, et al. Non-Alzheimer neurodegenerative pathologies and their combinations are more frequent than commonly believed in the elderly brain: a community-based autopsy series. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(3):365-84.

Elobeid A, Libard S, Leino M, Popova SN, Alafuzoff I. Altered Proteins in the Aging Brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2016;75(4):316-25.

Abner EL, Kryscio RJ, Schmitt FA, Fardo DW, Moga DC, Ighodaro ET, et al. Outcomes after diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment in a large autopsy series. Ann Neurol. 2017;81(4):549-59.

White LR, Edland SD, Hemmy LS, Montine KS, Zarow C, Sonnen JA, et al. Neuropathologic comorbidity and cognitive impairment in the Nun and Honolulu-Asia Aging Studies. Neurology. 2016;86(11):1000-8.

Kapasi A, DeCarli C, Schneider JA. Impact of multiple pathologies on the threshold for clinically overt dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134(2):171-86.

Spires-Jones TL, Attems J, Thal DR. Interactions of pathological proteins in neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134(2):187-205.

Dickson DW, Braak H, Duda JE, Duyckaerts C, Gasser T, Halliday GM, et al. Neuropathological assessment of Parkinson’s disease: refining the diagnostic criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(12):1150-7.

McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Halliday G, Taylor JP, Weintraub D, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89(1):88-100.

Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388(6645):839-40.

Baba M, Nakajo S, Tu PH, Tomita T, Nakaya K, Lee VM, et al. Aggregation of alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies of sporadic Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Am J Pathol. 1998;152(4):879-84.

Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(2):197-211.

Del Tredici K, Rüb U, De Vos RA, Bohl JR, Braak H. Where does parkinson disease pathology begin in the brain? J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61(5):413-26.

Braak H, de Vos RA, Bohl J, Del Tredici K. Gastric alpha-synuclein immunoreactive inclusions in Meissner’s and Auerbach’s plexuses in cases staged for Parkinson’s disease-related brain pathology. Neurosci Lett. 2006;396(1):67-72.

McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O'Brien JT, Feldman H, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1863-72.

Hamilton RL. Lewy bodies in Alzheimer’s disease: a neuropathological review of 145 cases using alpha-synuclein immunohistochemistry. Brain Pathol. 2000;10(3):378-84.

Nelson PT, Abner EL, Patel E, Anderson S, Wilcock DM, Kryscio RJ, et al. The Amygdala as a Locus of Pathologic Misfolding in Neurodegenerative Diseases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2018;77(1):2-20.

Uchikado H, Lin WL, DeLucia MW, Dickson DW. Alzheimer disease with amygdala Lewy bodies: a distinct form of alpha-synucleinopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65(7):685-97.

Leverenz JB, Hamilton R, Tsuang DW, Schantz A, Vavrek D, Larson EB, et al. Empiric refinement of the pathologic assessment of Lewy-related pathology in the dementia patient. Brain Pathol. 2008;18(2):220-4.

Beach TG, Adler CH, Lue L, Sue LI, Bachalakuri J, Henry-Watson J, et al. Unified staging system for Lewy body disorders: correlation with nigrostriatal degeneration, cognitive impairment and motor dysfunction. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117(6):613-34.

Attems J, Toledo JB, Walker L, Gelpi E, Gentleman S, Halliday G, et al. Neuropathological consensus criteria for the evaluation of Lewy pathology in post-mortem brains: a multi-centre study. Acta Neuropathol. 2021;141(2):159-72.

Kraybill ML, Larson EB, Tsuang DW, Teri L, McCormick WC, Bowen JD, et al. Cognitive differences in dementia patients with autopsy-verified AD, Lewy body pathology, or both. Neurology. 2005;64(12):2069-73.

Emre M, Aarsland D, Brown R, Burn DJ, Duyckaerts C, Mizuno Y, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22(12):1689–707; quiz 837.

Goetz CG, Emre M, Dubois B. Parkinson's disease dementia: definitions, guidelines, and research perspectives in diagnosis. Ann Neurol. 2008;64 Suppl 2:S81-92.

Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314(5796):130-3.

Nelson PT, Trojanowski JQ, Abner EL, Al-Janabi OM, Jicha GA, Schmitt FA, et al. “New Old Pathologies”: AD, PART, and Cerebral Age-Related TDP-43 With Sclerosis (CARTS). J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2016;75(6):482-98.

Nelson PT, Smith CD, Abner EL, Wilfred BJ, Wang WX, Neltner JH, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis of aging, a prevalent and high-morbidity brain disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(2):161-77.

Nag S, Yu L, Wilson RS, Chen EY, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. TDP-43 pathology and memory impairment in elders without pathologic diagnoses of AD or FTLD. Neurology. 2017;88(7):653-60.

Josephs KA, Murray ME, Whitwell JL, Tosakulwong N, Weigand SD, Petrucelli L, et al. Updated TDP-43 in Alzheimer’s disease staging scheme. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(4):571-85.

Kovacs GG, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Protein astrogliopathies in human neurodegenerative diseases and aging. Brain Pathol. 2017;27(5):675-90.

Mckee AC, Abdolmohammadi B, Stein TD. The neuropathology of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;158:297-307.

Katz DI, Bernick C, Dodick DW, Mez J, Mariani ML, Adler CH, et al. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for Traumatic Encephalopathy Syndrome. Neurology. 2021;96(18):848-63.

Stein TD, Crary JF. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy and Neuropathological Comorbidities. Semin Neurol. 2020;40(4):384-93.

Kovacs GG, Ferrer I, Grinberg LT, Alafuzoff I, Attems J, Budka H, et al. Aging-related tau astrogliopathy (ARTAG): harmonized evaluation strategy. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(1):87-102.

Kling MA, Trojanowski JQ, Wolk DA, Lee VM, Arnold SE. Vascular disease and dementias: paradigm shifts to drive research in new directions. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):76-92.

Jellinger KA, Attems J. Prevalence and pathology of vascular dementia in the oldest-old. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21(4):1283-93.

Toledo JB, Arnold SE, Raible K, Brettschneider J, Xie SX, Grossman M, et al. Contribution of cerebrovascular disease in autopsy confirmed neurodegenerative disease cases in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centre. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 9):2697-706.

Nelson PT, Head E, Schmitt FA, Davis PR, Neltner JH, Jicha GA, et al. Alzheimer’s disease is not “brain aging”: neuropathological, genetic, and epidemiological human studies. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121(5):571-87.

Snowdon DA, Greiner LH, Mortimer JA, Riley KP, Greiner PA, Markesbery WR. Brain infarction and the clinical expression of Alzheimer disease. The Nun Study. JAMA. 1997;277(10):813-7.

Mungas D, Reed BR, Ellis WG, Jagust WJ. The effects of age on rate of progression of Alzheimer disease and dementia with associated cerebrovascular disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(8):1243-7.

Petrovitch H, Ross GW, Steinhorn SC, Abbott RD, Markesbery W, Davis D, et al. AD lesions and infarcts in demented and non-demented Japanese-American men. Ann Neurol. 2005;57(1):98-103.

Schneider JA, Boyle PA, Arvanitakis Z, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Subcortical infarcts, Alzheimer’s disease pathology, and memory function in older persons. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(1):59-66.

Deramecourt V, Slade JY, Oakley AE, Perry RH, Ince PG, Maurage CA, et al. Staging and natural history of cerebrovascular pathology in dementia. Neurology. 2012;78(14):1043-50.

Chui HC, Zarow C, Mack WJ, Ellis WG, Zheng L, Jagust WJ, et al. Cognitive impact of subcortical vascular and Alzheimer's disease pathology. Ann Neurol. 2006;60(6):677-87.

Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Arvanitakis Z, Boyle PA, de Toledo-Morrell L, Schneider JA. Selected findings from the Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33 Suppl 1:S397-403.

Blevins BL, Vinters HV, Love S, Wilcock DM, Grinberg LT, Schneider JA, et al. Brain arteriolosclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2021;141(1):1-24.

Carmona S, Hardy J, Guerreiro R. The genetic landscape of Alzheimer disease. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;148:395-408.

Verghese PB, Castellano JM, Holtzman DM. Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(3):241-52.

Yeh FL, Hansen DV, Sheng M. TREM2, Microglia, and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Trends Mol Med. 2017;23(6):512-33.

Escartin C, Galea E, Lakatos A, O'Callaghan JP, Petzold GC, Serrano-Pozo A, et al. Reactive astrocyte nomenclature, definitions, and future directions. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24(3):312-25.

Chen Y, Colonna M. Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease at single-cell level. Are there common patterns in humans and mice? J Exp Med. 2021;218(9).

Prokop S, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Neuroimmune interactions in Alzheimer’s disease-New frontier with old challenges? Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2019;168:183-201.

Crook R, Verkkoniemi A, Perez-Tur J, Mehta N, Baker M, Houlden H, et al. A variant of Alzheimer's disease with spastic paraparesis and unusual plaques due to deletion of exon 9 of presenilin 1. Nat Med. 1998;4(4):452-5.

Lee EB. Integrated neurodegenerative disease autopsy diagnosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;135(4):643-6.

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803-20.

Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ, Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021.

Pantanowitz L, Sharma A, Carter AB, Kurc T, Sussman A, Saltz J. Twenty Years of Digital Pathology: An Overview of the Road Travelled, What is on the Horizon, and the Emergence of Vendor-Neutral Archives. J Pathol Inform. 2018;9:40.

Zarella MD, Bowman D, Aeffner F, Farahani N, Xthona A, Absar SF, et al. A Practical Guide to Whole Slide Imaging: A White Paper From the Digital Pathology Association. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143(2):222-34.

Hamilton PW, Wang Y, McCullough SJ. Virtual microscopy and digital pathology in training and education. APMIS. 2012;120(4):305-15.

Tang Z, Chuang KV, DeCarli C, Jin LW, Beckett L, Keiser MJ, et al. Interpretable classification of Alzheimer's disease pathologies with a convolutional neural network pipeline. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2173.

Neltner JH, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Denison SK, Anderson S, Patel E, et al. Digital pathology and image analysis for robust high-throughput quantitative assessment of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71(12):1075-85.

Crist AM, Hinkle KM, Wang X, Moloney CM, Matchett BJ, Labuzan SA, et al. Transcriptomic analysis to identify genes associated with selective hippocampal vulnerability in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2311.

Johnson TS, Xiang S, Helm BR, Abrams ZB, Neidecker P, Machiraju R, et al. Spatial cell type composition in normal and Alzheimers human brains is revealed using integrated mouse and human single cell RNA sequencing. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):18014.

Young AMH, Kumasaka N, Calvert F, Hammond TR, Knights A, Panousis N, et al. A map of transcriptional heterogeneity and regulatory variation in human microglia. Nat Genet. 2021;53(6):861-8.

Chen WT, Lu A, Craessaerts K, Pavie B, Sala Frigerio C, Corthout N, et al. Spatial Transcriptomics and In Situ Sequencing to Study Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell. 2020;182(4):976-91.e19.

Hampel H, Nisticò R, Seyfried NT, Levey AI, Modeste E, Lemercier P, et al. Omics sciences for systems biology in Alzheimer’s disease: State-of-the-art of the evidence. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;69:101346.

Jack CR, Knopman DS, Weigand SD, Wiste HJ, Vemuri P, Lowe V, et al. An operational approach to National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association criteria for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(6):765-75.

Nicoll JA, Wilkinson D, Holmes C, Steart P, Markham H, Weller RO. Neuropathology of human Alzheimer disease after immunization with amyloid-beta peptide: a case report. Nat Med. 2003;9(4):448-52.

Salloway S, Cummings J. Aducanumab, Amyloid Lowering, and Slowing of Alzheimer Disease. Neurology. 2021.

Levites Y, Das P, Price RW, Rochette MJ, Kostura LA, McGowan EM, et al. Anti-Abeta42- and anti-Abeta40-specific mAbs attenuate amyloid deposition in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(1):193-201.

Dhillon JS, Riffe C, Moore BD, Ran Y, Chakrabarty P, Golde TE, et al. A novel panel of α-synuclein antibodies reveal distinctive staining profiles in synucleinopathies. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184731.

Trejo-Lopez JA, Sorrentino ZA, Riffe CJ, Lloyd GM, Labuzan SA, Dickson DW, et al. Novel monoclonal antibodies targeting the RRM2 domain of human TDP-43 protein. Neurosci Lett. 2020;738:135353.

Josephs KA et al. Rates of hippocampal atrophy and presence of post-mortem TDP-43 in patients with Alzheimer's disease: a longitudinal retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(11):917-924. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30284-3

Josephs KA et al. TAR DNA-binding protein 43 and pathological subtype of Alzheimer's disease impact clinical features. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(5):697-709. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24493

Kapasi, A., et al., Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, ADNC pathology, and cognitive decline in aging. Neurology 2020;95(14):e1951-e1962. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000010454

Nag S et al. TDP-43 pathology and memory impairment in elders without pathologic diagnoses of AD or FTLD. Neurology 2017;88(7):653-660. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003610

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (P30AG066506, P50AG047266).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Trejo-Lopez, J.A., Yachnis, A.T. & Prokop, S. Neuropathology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 19, 173–185 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-021-01146-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-021-01146-y