Abstract

The present paper aims to explore the perception of fairness in conflicting claims problems (O’Neill in Math Soc Sci 2(4):345–371, 1982). To do so, we present a questionnaire given to a large heterogeneous group of people (students, employees, retirees). Distributive justice criteria are studied through different ways of distributing scarce resources, and we analyse whether the population’s response patterns are conditioned by specific features of the economic context. We find that proportional allocation is generally considered the fairest way of distributing resources. However, the principle of proportionality is abandoned by part of the population when claims represent needs and claimants have scarce resources. Moreover, we observe that age, employment status and education levels significantly influence the perception of fairness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A conflicting claims problem is a distribution problem in which the available amount to be shared, the endowment, is insufficient to cover the agents’ acquired rights, their claims. A solution associates a division among the claimants of the endowment for each conflicting claims problem. This model describes a great variety of situations. The distribution of the net worth of a bankrupt firm among its creditors has become so representative of a conflicting claims problem that it is referred to as a “bankruptcy problem”.

An illustrative example is reductions in fishing quotas, where the agents’ claims can be understood as previous catches, and the endowment is the new (lower) level of joint captures (Gallastegui et al. 2003; Iñarra and Skonhof 2008). Similarly, the establishment of milk quotas among EU members, enacted in 1984, led to a claims conflict. Each member state was given a reference quantity which was then allocated to individual producers. The initial quotas were not sufficiently restrictive to remedy surplus production and they had to be cut twice more, in the late 1980s and early 1990s.Footnote 1 In both examples, proportionality was the main principle applied. Another very different situation is the 9/11 Victim Compensation Fund, where the income each victim would have earned in their lifetime was estimated to establish the legal right to be compensated, that is, the individual claim.Footnote 2

Other relevant practical cases involving more complex rationing situations are water distribution during periods of drought and resource allocation procedures in the public healthcare sector (see, for instance, Hougaard et al. 2012; Moreno-Ternero and Roemer 2012). The design of efficient radio resource management policies to provide the best quality service while guaranteeing user fairness and environmental safety has also been modelled as a problem with conflicting claims (see Lucas-Estañ et al. 2012; Giménez-Gómez et al. 2016, respectively).

An alternative interpretation of a conflicting claims problem comes from the analysis of taxation systems (Young 1987, 1988). In this framework, the available amount to be shared is the after-tax aggregate income and the acquired rights are pre-tax individual incomes. Therefore, an allocation of the after-tax aggregate income implies a distribution of the tax burden among taxpayers.

The axiomatic analysis of such problems, following the seminal paper by O’Neill (1982), has provided extensive literature to identify well-behaved solutions. Thomson (2019) is a recent, complete, in-depth survey. Among all the solutions, the most prominent ones are the proportional, constrained equal awards, constrained equal losses and Talmud rules. The proportional rule states that the endowment should be shared in proportion to the claims. The constrained equal awards and the constrained equal losses rules are based on the distributive justice principle of equality. Specifically, the former shares the endowment equally among claimants, stipulating that no claimant can receive a larger amount than their claim. The latter recommends equal division of the incurred losses (the amount of the claim not honoured), establishing that no claimant can end up with a negative amount. Finally, the Talmud rule shares the endowment, when it is less than half of the aggregate claim (the midpoint), applying constrained equal awards but considering half of each of the claims (i.e. the endowment is shared equally among claimants, and no claimant can receive a larger amount than half of their claim); otherwise, each agent receives half of their claim plus the amount provided by the constrained equal losses rule applied to the remaining endowment and claims.

Another research line of conflicting claims problems is empirical analysis, where two different approaches to studying the acceptance of the main rules proposed in the theoretical literature can be found: (i) questionnaires, and (ii) laboratory experiments. Gaertner and Schokkaert (2012) is a survey about empirical social choice.Footnote 3

The questionnaire approach, inspired by the seminal paper by Yaari and Bar-Hillel (1984), gathers information about moral intuitions and distributive justice perceptions. Therefore, respondents solve hypothetical problems from the point of view of external observers or arbitrators (see, for instance, Amiel et al. 2008).Footnote 4 In our context, this approach has been previously carried out by Schokkaert and Overlaet (1989), Gächter and Riedl (2006), Bosmans and Schokkaert (2009), Herrero et al. (2010), Gaertner and Schwettmann (2017) and Tarroux (2019) among others.

The experimental approach focuses on the justification of rules based on actual behaviour. Participants have to solve hypothetical problems in which they are personally involved, and their decisions are usually influenced by both moral and selfish considerations. Although experimental economics had been firmly established in the 1980s when conflicting claims problems were introduced, to our knowledge, the first experiments with them were conducted by Gächter and Riedl (2006) and Herrero et al. (2010). Other recent works in this line are Kittel et al. (2017), Büyükboyacı et al. (2019), Cappelen et al. (2019), Gaertner et al. (2019) and Gantner et al. (2019).

The purpose of this paper is to contribute to the analysis of the perception of justice in conflicting claims problems through the study of questionnaires. Following Bosmans and Schokkaert (2009), we focus on between-context uniformity, that is, given a fixed mathematical formulation of a problem with conflicting claims, we study the influence of differences in the economic context.Footnote 5 Specifically, these authors consider two versions of a claims problem. In the firm version, three firm owners have to distribute a loss. In the pensions version, a shortage of funds has to be distributed among three pensioners. These two versions differ in several aspects: (i) the origin of the claims in the firm version is contributions but, in the pension version, the origin of the claims is not explicit (the authors say that in the firm version respondents are likely to interpret that the differences between claims are caused more by what is deserved and less by talent than in the pensions version); (ii) in the firm version, it is specified that each of the three owners also has other sources of income but no information about this aspect is provided in the pensions version (according to the authors, respondents are likely to consider pensions as the only source of income); and, (iii) in the firm version, the time is one month and in the pensions version the time is much longer. Therefore, the root cause of the different responses in both versions cannot be clearly identified.

In our analysis of people’s response patterns solving conflicting claims problems as “outsiders”, we attempt to achieve two objectives. First, we want to isolate the influence of “pure” background story from both the nature of the claims and the agents’ economic positions. Second, we want to find out whether there are any significant differences in people’s moral intuition due to their personal characteristics: gender, age, education level and employment status.

Regarding our first purpose, we provide enough information about each specific context to avoid the respondents’ personal interpretations of undefined aspects. We have designed eight different economic contexts by combining all of the following pairs of specifications of the general background story, origin of claims and agents’ economic position:

-

(i)

General background stories: a company that cannot honour the committed salaries of the workers of its advertising department versus a mutual benefit society that cannot fully pay the entitled retirement pensions of its members.

-

(ii)

Origins of claims: rights that come from differences in effort (hours worked for the firm and monetary contributions to the mutual benefit society) versus rights that represent differences in some agents’ characteristics that are outside their control (publicists’ creative abilities or retirees’ family situations); and

-

(iii)

Agents’ economic positions: claimants that have other sources of income, in addition to salary or pension, that allow them to cover their basic needs versus claimants that have only their salaries or pensions.

In this regard, Schokkaert and Overlaet (1989) are pioneers in confronting respondents with several versions of a conflicting claims problem. The formal characteristics of their claims problems are the same in the different versions, but the reason for the differences in claims varies. In one version, claims reflect differences in hours worked, while in another version, claims reflect differences in talent. However, to the best of our knowledge, the influence of agents’ economic positions when solving conflicting claims problems has not been analysed. Widerquist et al. (2013) provide clear evidence about how financial status quo could affect the subjective perception of fairness. Specifically, they consider reestablishing status quo as a step towards justice since solidarity is inversely related to family revenues. From the theoretical point of view, Timoner and Izquierdo (2016) extend the standard conflicting claims problems where agents are not only identified by their respective claims to some amount of a scarce resource, but also by exogenous ex-ante conditions, initial stock of resource or agents’ net worth, for example.

Concerning our second purpose, we do not restrict our sample to a particular population such as students, as is common in empirical social choice. Our questionnaires are aimed at a heterogeneous set of participants, pursuing global representation of all the social strata (see, for instance, Schokkaert and Capeau 1991). To our knowledge, this is the first work on conflicting claims problems that illustrates the influence of some personal characteristics on moral intuition, although the role they play in the theory of allocation decisions, as summarised by Hegtvedt and Cook (2001), has been extensively analysed.

This paper is organised as follows. Section 2 introduces the theoretical model. Section 3 explains the design of our questionnaires. Section 4 presents and discusses the between-context uniformity results and the influence of personal characteristics on distributive justice principles. Finally, Sect. 5 concludes. The questionnaires and some sample specifications are provided in the Appendices.

2 The theoretical model

Here, we present the mathematical formulation of the conflicting claims problems and the rules that are used throughout the paper. We provide a concise axiomatic analysis of the rules using minimal requirements and some properties that lead to their selected characterisations. Finally, we describe the main contributions of a Lorenz comparison of the rules.

2.1 Conflicting claims problem

Consider a set of agents \(N=\left\{ 1,2,\ldots ,n\right\} \) and an amount \(E\in {\mathbb {R}}_{+}\) of a perfectly divisible resource, the endowment, that has to be allocated among the agents. Each agent has a claim, \(c_i\in {\mathbb {R}}_{+}\) on E. Let c \(=(c_i)_{i\in N} \) be the claims vector and \(C=\sum \nolimits _{i\in N}c_{i}\).

A conflicting claims problem is a pair (E, c) with \(C>E\). Without loss of generality, we index claims in increasing order, \(c_{1}\le c_{2}\le \cdots \le c_{n}\) , and \({\mathcal {B}}\) denotes the set of all conflicting claims problems.

2.2 Rules

Given a conflicting claims problem, a rule associates a distribution of the endowment among the agents of each problem.

A rule is a single-valued function \(\varphi :{\mathcal {B}} \rightarrow {\mathbb {R}}_{+}^{n} \) such that for all \(i\in N\), \(\sum \nolimits _{i\in N}\varphi _{i}(E,c)=E\) (efficiency); and \(0\le \varphi _{i}(E,c)\le c_{i}\), (non-negativity and claim-boundedness).

The proportional (P) rule (see Thomson 2015) recommends the distribution of the endowment that is proportional to the claims: for each \((E,c)\in {\mathcal {B}}\) and each \(i\in N\), \(P_{i}(E,c) = \lambda c_{i},\) where \(\lambda =\dfrac{E}{C}.\)

The following two rules are supported by many authors, including Maimonides, 12th century (see Aumann and Maschler 1985).

The constrained equal awards (CEA) rule proposes equal awards to all the agents, subject to no-one receiving more than their claim: for each (E, c) \(\in {\mathcal {B}}\) and each \(i\in N,\) \({\mathrm {CEA}}_{i}(E,c)= \min \left\{ c_{i},\mu \right\} ,\) where \(\mu \) is such that \(\sum \nolimits _{i\in N}\min \left\{ c_{i},\mu \right\} =E.\)

The constrained equal losses (CEL) rule chooses the awards vector at which all the agents incur equal losses, subject to no-one receiving a negative amount: for each \((E,c)\in {\mathcal {B}}\) and each \(i\in N\), \({\mathrm {CEL}}_{i}(E,c)= \max \left\{ 0,c_{i}-\mu \right\} , \) where \(\mu \) is such that \(\sum \nolimits _{i\in N} \max \left\{ 0,c_{i}-\mu \right\} =E\).

It is noteworthy that the CEA and the CEL rules are dual, that is, the gains of the agents when the CEA rule is applied to divide what is available, E, are identical to their gains when the CEL rule is applied to divide what is missing, \(L = C - E\). Formally, for each \((E,c)\in {\mathcal {B}}\), \({\mathrm {CEA}}(E,c)=c-{\mathrm {CEL}}(C-E,c)\).

The Talmud (T) rule (Aumann and Maschler 1985) proposes that if the endowment is not sufficient to satisfy the half-sum of the claims, the CEA rule should be applied, taking into account the whole endowment (E) and half of each claim (c/2). Note that this condition implies that no agent will receive more than half of their claim. Whenever the endowment is larger than the half-sum of the claims, all the agents receive half of their claims plus the amount provided by the CEL rule applied to distribute the remaining endowment, taking into account only half of each claim: for each \((E,c)\in {\mathcal {B}},\) and each \(i\in N,\) \(T_{i}(E,c)= {\mathrm {CEA}}_{i}(E,c/2)\) if \(E\le C/2\); and \(T_{i}(E,c) = c_{i}/2+{\mathrm {CEL}}_{i}(E-C/2,c/2)\), otherwise.

We note that, although the P, CEA and CEL rules have been widely investigated in the literature on conflicting claims problems (Gächter and Riedl 2006; Bosmans and Schokkaert 2009; Herrero et al. 2010 among others), we also consider the Talmud rule. “It is socially unjust for different creditors to be on opposite sides of the halfway point, C/2” (Aumann and Maschler 1985). Furthermore, as Schokkaert and Overlaet (1989) point out, people react differently to gains and losses, which underlies the Talmud rule. From an implementation point of view, Gallastegui et al. (2003) and Giménez-Gómez et al. (2016) show that this rule has been proposed as a solution to important real distribution problems.

2.3 Axiomatic analysis

To axiomatically analyse the aforementioned rules, we propose two sets of principles: minimal requirements and additional principles.Footnote 6

The minimal requirements set consists of the properties: equal treatment of equals, anonymity, order preservation and resource monotonicity. Note that these principles ensure that: (i) agents with the same claim receive the same award; (ii) there is no discrimination among the agents, meaning that only the claim matters; (iii) the agents with larger claims do not receive a smaller allocation than agents with smaller claims; and (iv) no agent loses out when the endowment to be distributed is larger. As Table 1 depicts, all these properties are satisfied by the rules presented. It is worth noting that although these properties cannot be used to reject or select a solution, they are generally accepted in the literature, and no solution violating them would be accepted. We explain these properties below.

Equal treatment of equals implies that agents with equal claims should receive the same awards: for each \((E,c)\in {\mathcal {B}}\), and each \(\left\{ i,j\right\} \subseteq N\), if \(c_{i}=c_{j}\), then \(\varphi _{i}(E,c)=\varphi _{j}(E,c).\)

Anonymity states that the awards received by the agents should depend only on their claims, and not on their identities: for each \((E,c)\in {\mathcal {B}}\), each \(\pi \in \Pi ^{N}\), and each \(i\in N\), \(\varphi _{\pi (i)}(E,(c_{\pi (i)})_{i\in N})=\varphi _{i}(E,c),\) where \(\Pi ^{N}\) is the class of all permutations of N.

Order preservation (Aumann and Maschler 1985) means respecting the ordering of the claims, i.e. if agent \(i's\) claim is at least as large as agent \(j's\) claim, agent i should receive and lose at least as much as agent j, respectively: for each \((E,c)\in {\mathcal {B}}\), and each \(i,j\in N\), such that \(c_{i}\ge c_{j}\), then \(\varphi _{i}(E,c)\ge \varphi _{j}(E,c),\) and \(c_{i}-\varphi _{i}(E,c)\ge c_{j}-\varphi _{j}(E,c).\)

Resource monotonicity (Curiel et al. 1987) states that if the endowment increases, no agent can be worse off: for each (E, c) and \((E',c)\) \(\in {\mathcal {B}}\), and each \(i\in N\), such that \( E\le E' \le C\), then \(\varphi _{i}(E,c)\le \varphi _{i}(E',c)\).

Some additional principles used to axiomatically analyse a rule are: composition up, composition down, claims truncation invariance, self-duality, consistency and minimal rights first.

Composition up (Young 1987) states that if the endowment increases after it has been divided among the agents, there are two ways to redistribute the new endowment that propose the same allocation: (i) to cancel the initial division and recalculate the awards for the revised endowment; or, (ii) to let each agent keep their initial award, revise their claim downwards by this award and reapply the solution to divide the additional endowment. For each \((E,c)\in {\mathcal {B}},\) each \(i\in N\), and each \(0\le E\le E^{\prime }\) such that \(\sum _{i \in N} c_i\ge E',\) then \(\varphi _{i}(E^{\prime },c)=\varphi _{i}(E,c)+\varphi _{i}(E^{\prime }-E,c-\varphi (E,c)).\)

Composition down (Kalai 1977; Moulin 2000) establishes that if the endowment decreases after it has been divided among the agents, there are two ways to redistribute the new endowment that propose the same allocation: (i) to cancel the initial distribution and apply the solution to the new situation; or, (ii) to consider the initial allocation as the agents’ claims on the revised problem. For each \((E,c)\in {\mathcal {B}},\) each \(i\in N\), and each \(0\le E^{\prime }\le E,\) \(\varphi _{i}(E^{\prime },c)=\varphi _{i}(E^{\prime },\varphi (E,c)).\)

Claims truncation invariance (Curiel et al. 1987) considers that the part of a claim that is above the amount to divide should be ignored: for each \((E,c)\in {\mathcal {B}}\) and each \(i\in N\), \(\varphi _{i}(E,c) = \varphi _{i}(E,t(E,c)),\) where \(t(E,c)= (t_{i}(E,c))_{i \in N}\), and \(t_{i}(E,c) = \min \{E,c_{i}\}\).

Self-duality (Aumann and Maschler 1985) implies that the gains of the agents when a rule is applied to the problem of dividing “what is available (E)”are identical to their gains when the rule is applied to divide “what is missing (\(L = C - E\))”: for each \((E,c)\in {\mathcal {B}}\) and each \(i\in N\), \(\varphi _{i}(E,c)=c_{i}-\varphi _{i}(\sum _{i\in N}c_{i}-E,c).\)

Consistency (O’Neill 1982) states that if some agents leave the problem, the remaining agents should not be affected. For each \((E,c)\in {\mathcal {B}}\) and each \(N'\subset N\), if \(x=\varphi (E,c)\), then \( x_{N'}=\varphi (\sum _{N'}{x_i}, c_{N'}).\)

Minimal rights first (Curiel et al. 1987) establishes that a rule can be calculated either directly, or each agent is first assigned their minimal right (\(m_{i}(E,c) = \max \{E-\sum _{N \setminus {i}}c_{j},0\}\), and \(m(E,c)= (m_{i}(E,c))_{i \in N}\)); then, after revising the claims down by the minimal rights, the residual endowment is distributed considering the revised claims. For each \((E,c)\in {\mathcal {B}}\), \(\varphi (E,c)=m(E,c)+\varphi (E-\sum _{i\in N} m_{i}(E,c), c-m(E,c)).\)

Table 1 depicts which of the principles mentioned above are fulfilled by the proposed solutions.Footnote 7

Note that the proposed rules satisfy all the minimal requirements. The additional properties are normally used to characterise the rules, i.e. to find out the correspondence between the combined fulfilment of properties and a rule. Accordingly, the proportional rule is the only rule satisfying self-duality and composition up (Young 1988). The constrained equal awards rule is the only rule satisfying equal treatment of equals, claims truncation invariance and composition up (Dagan 1996). The constrained equal losses rule is the only rule satisfying equal treatment of equals, minimal rights first and composition down (Dagan 1996). Finally, the Talmud rule is the only rule satisfying equal treatment of equals, claims truncation invariance, minimal rights first and consistency (Dagan 1996).

2.4 Equality

Following Nozick (1974), “the complete principle of distributive justice would say simply that a distribution is just if everyone is entitled to the holdings they possess under the distribution”. Hence, to compare which rule provokes greater acceptance among the different agents involved in the endowment distribution, we introduce the Lorenz dominance. This criterion is a key concept in the literature on income distribution (see, for instance, Sen 1973), and it is used to check whether a solution is more favourable to smaller claimants than larger ones. So, a Lorenz dominant solution is intended to equalise the allocations among claimants, regardless of their claims. Let \({\mathbb {R}}^{n}_{\le }\) be the set of positive n-dimensional vectors \(x = \left( x^{1}, x^{2},\ldots , x_{n}\right) \) increasingly ordered, i.e. \(0 < x_{1}\le x_{2} \le \cdots \le x_{n}\). Let x and y be in \({\mathbb {R}}^{n}_{\le }\). We say that x Lorenz-dominates y, denoted by \(x \succ _{L} y\), if for each \(k = 1, 2,\ldots , n-1\), \(x_{1} + x_{2} +\cdots + x_{k} \ge y_{1} + y_{2} +\ldots + y_{k} \quad \text {and} \quad \sum _{i\in N} x_i = \sum _{i\in N} y_i.\) If \(x \succ _{L} y\) and \(x\ne y,\) then at least one of these \(n-1\) inequalities is a strict inequality. Given two rules, \(\varphi \) and \(\psi \), it is said that \(\varphi \) Lorenz-dominates \(\psi \), \(\varphi \succ _{L} \psi \), if \(\varphi (E,c) \succ _{L} \psi (E,c)\), for each conflicting claims problem (E, c). Focusing on the ordered vector of losses, parallel rankings can be defined and we can speak of Lorenz domination among loss vectors and among rules in terms of losses.

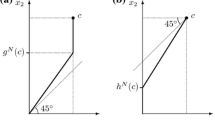

In this regard, Bosmans and Lauwers (2011) obtain a Lorenz dominance comparison among several rules in terms of awards vectors:

In fact, these authors characterise the CEA and CEL rules from the point of view of the Lorenz order as follows. For each problem, the CEA awards vector is the only one that maximises the Lorenz order among all the awards vectors and the only one that maximises the Lorenz order for losses among all the awards vectors satisfying order preservation. Since the CEA and CEL rules are dual, for each problem, the CEL awards vector is the only one that minimises the Lorenz order for losses among all the awards vectors and the only one that minimises the Lorenz order among all the awards vectors satisfying order preservation.

In the case of the P and T rules, whenever the aggregate claim C exceeds twice the estate E, \(C \ge 2E\), \(T \succ _{L} P\), and vice versa. In the general case, the P and T rules are not related, but both provide more egalitarian allocations than the CEL rule and less egalitarian than the CEA rule. Finally, additional recent contributions in this context can be found in Hougaard and Østerdal (2005), Moreno-Ternero and Villar (2006), Ju and Moreno-Ternero (2008), Kasajima and Velez (2010) and Thomson (2012), among others.

3 The questionnaires

The main characteristics of the questionnaires are presented below. First, we explain how the data have been collected. Second, we specify the eight economic contexts that we considered by combining different background stories, origins of claims and wealth situations. Finally, we present the structure of the questions to be addressed by the respondents.

3.1 Collecting data

We included heterogeneity by not restricting our sample to a particular population, with the aim of identifying the justice principle of society as a whole. In doing so, we could analyse whether there are significant differences in people’s choices due to the following characteristics: age, gender, education level, household income, employment status, city and country of habitual residence and being a supportive person.

The data were collected using an online survey because it is the best way to get answers from different regions and countries. There are several sites for this purpose, such as Free Online Surveys, SurveyMonkey, SurveyPlanet and the one that we selected for our study, Google Drive.

We published a general description of the study on our university website (see the first part of Appendix 1) and sent the web link by email to our contacts, members of our university and colleagues in other universities, encouraging all of them to distribute the link among their professional and personal contacts. Apart from this, we published the link on social networks, and it was widely spread on Twitter.

At the end of the description page, there was a command button to access the survey itself. This button, using the PHP programming language, assigned a random questionnaire to each person to obtain a similar number of answers for all the different questionnaires. The programming routine also collected the assigned questionnaire, the date and time the button was pressed and the response time. Using this information, we know that 1067 people pressed the button and accessed the questionnaires. Among those who started a questionnaire, our analysis only considers 575 responses. One part of the remaining 492 accesses did not submit their answers, and another group was not considered because the respondents took less than 10 minutes to complete the questionnaire. We estimated that a minimum of ten minutes would be necessary to do it properly. In a few cases, the respondents did not answer all the questions or omitted some personal characteristics. Due to the fact that the answers to different questions were independent, they can be used for the general analysis. Nonetheless, of all the personal characteristics that respondents were asked about, we were not able to study the influence of household income, city and country of habitual residence or whether or not the respondents consider themselves to be supportive people because we did not obtain a sufficient number of responses to ensure a significant analysis.

3.2 Defining contexts

The questionnaires were designed to check the between-context uniformity of conflicting claims problems. That is, we wanted to find the answer to the following question: Do people’s perceptions of distributive justice depend on the economic context?

Firstly, two background stories were presented, as in the study by Bosmans and Schokkaert (2009): an advertising department in a private company and a mutual benefit society. In both of them, three agents are involved. In the first story, they are employees and in the second, retirees.

- F:

-

Employees who are working in an advertising department and the salaries that the firm was committed to pay them cannot be honoured.

- M:

-

Retirees who are members of a mutual benefit society that cannot face up to the committed retirement pensions.

Secondly, following the study by Schokkaert and Overlaet (1989), we consider two different origins of the claims: the agents’ effort, materialised in hours worked or monetary contributions (depending on the background story) and some characteristics outside the agents’ control.

- E:

-

The committed payments are related to the number of hours worked, in the case of employees, and to the retirees’ monetary contributions to the mutual benefit society.

- S:

-

The committed payments are related to the employees’ creative ability and the retirees’ family situation.

Finally, we contemplate two different status quo distributions of agents’ wealth: one that allows them to have their basic needs met and another where they have nothing, that is, their income is only what they receive from solving the conflicting claims problem.

- Y:

-

The agents can meet their basic needs with alternative sources of income, other than what they receive from the conflicting claims problem.

- N:

-

The agents have no other sources of income, apart from what they receive from the conflicting claims problem.

By combining different background stories, origins of the claims and wealth status quo, we obtain eight different contexts, as Fig. 1 summarises.

Remark 1

Three characteristics of the agents’ rights should be highlighted:

-

1.

In all the contexts, the rights are payment commitments.

-

2.

The rights are either a result of the agents’ active involvement (in the FE and ME contexts, they come from the agents’ efforts and their monetary contributions, respectively) or from some features outside the agents’ control (in the FS and MS contexts, they come from the agents’ creative ability and from their family situations, respectively).

-

3.

The rights represent hours worked (FE context), creative ability (FS context), monetary contribution (ME context) or basic needs (MS context).

It is worth mentioning that among all the considered contexts, only in the MSN context do the rights represent basic needs that cannot be met in any way.

3.3 Designing the questionnaires

The respondents act as external arbitrators who randomly consider one of the eight possible contexts. They have to evaluate whether each of the four proposed rules is fair, and which one is the fairest.

Concretely, each of the respondents faces one of the two economic background stories, where the origin of the acquired rights is explained. Below, we show one of the questionnaires (see Appendix 1 for a full description of all the questionnaires).

The advertising department of a private company placed in Spain consists of three people with the following characteristics: same qualification level, similar family situation, same creative ability, none of them has another source of income, and all of them live in Spain.

The company committed to pay them €120,000 per year, an amount that it was decided to distribute according to the number of hours worked by each of them as follows: (30,000; 39,000; 51,000). That is: publicist 1: €30,000, publicist 2: €39,000, and publicist 3: €51,000.

However, due to causes beyond the control of the workers, the amount of money the company can spend this year on their salaries is lower, and this is the reason why the acquired rights cannot be fully met.

One of our main contributions is that we ask about fair criteria combining the different strengths of previous related works while providing new features, as detailed below.

Firstly, all of the respondents face an identical pair of problems in which they have to analyse fairness:

Consider the following two situations:

- A:

The company has only €75,000.

- B:

The company has only €45,000.

Secondly, as in Gächter and Riedl (2006) and Herrero et al. (2010), we provide different possible divisions of the resources according to the CEA, CEL and P rules in each of the conflicting claims problems, but we also consider the T rule. The explanation of each rule is given. Each respondent has to answer whether they think the recommendation of each rule is fair for both situations, taking into account that the fairness of one rule does not exclude the fairness of the others.

Next, different distributions for situations A and B are proposed. We want to know if you consider them fair or not. Note that you can select more than one option as fair. Moreover, if you select a pair of distributions as fair, it means that you think that the distributions proposed for both situations, A and B, are fair simultaneously.

Distribution 1: The available amount of money is equally divided among the three publicists.

- In situation A the distribution would be (25,000; 25,000; 25,000).

- In situation B the distribution would be (15,000; 15,000; 15,000).

Do you think this pair of distributions is fair? Yes / No.

Distribution 2: The three publicists lose the same amount of money.

- In situation A the distribution would be (15,000; 24,000; 36,000), because everyone loses €15,000.

- In situation B the distribution would be (5000; 14,000; 26,000), because everyone loses €25,000.

Do you think this pair of distributions is fair? Yes / No.

Distribution 3: If the available amount of money is greater than half of the originally committed amount (greater than €60,000), then the money is distributed so that each publicist loses the same amount (Distribution 2). If the available amount of money is less than half of the originally committed amount (less than €60,000), then the money is equally divided among publicists (Distribution 1).

- In situation A the distribution would be (15,000; 24,000; 36,000), because everyone loses €15,000.

- In situation B the distribution would be (15,000; 15,000; 15,000).

Do you think this pair of distributions is fair? Yes / No.

Distribution 4: The percentages of money that correspond to each publicist according to the original commitment are 25%, 32.5% and 42.5%, respectively. The final available amount is distributed using these percentages.

- In situation A the distribution would be (18,750; 24,375; 31,875).

- In situation B the distribution would be (11,250; 14,625; 19,125).

Do you think this pair of distributions is fair? Yes / No.

Remark 2

The specific data of the mathematical problems have been carefully determined to impose some constraints with the aim of showing the main features of the different rules in a clear way:

-

1.

The application of the principles of equal gains and equal losses is not affected by non-negativity and claim boundedness conditions. We use situations where the lower and upper thresholds from the definition of the CEA and CEL rules are not applied. Therefore, each of the agents receives (i) strictly positive awards, and (ii) a payoff smaller than their claim.

-

2.

The respondents’ final decision is not affected by the perverse effects that an agent’s zero payoff may cause. As, for instance, Bosmans and Schokkaert (2009) show a zero allocation causes people not to choose it. Therefore, we avoid using zero allocations to any of the agents. Moreover, to reveal that the CEL rule can lead to smaller claimants receiving a very small amount, we provide an allocation that recommends an agent’s payoff considerably lower than the legal annual minimum wage in Spain at the time the questionnaire was conducted. It amounted to €9, 182.80 (see Situation B in Distribution 2).

-

3.

The application of the T rule contemplates the two different criteria, equal gains and equal losses. By definition, if the endowment is smaller than half of the aggregate claim, the T rule proposes the CEA rule. Otherwise, it recommends the CEL rule. Therefore, we propose a distribution for each of the possible situations (see Situations A and B in Distribution 4, respectively).

-

4.

The application of the T rule is affected by neither the upper bound nor the lower bound conditions related to the half-sum of the claims. As in Point 2, we use a situation where the lower and upper thresholds from the definition of the T rule are not applied. Therefore, each of the agents receives a strictly positive award, either (i) smaller than their half-claim or (ii) larger than their half-claim.

Thirdly, it is also permissible to propose a different pair of divisions as fair through an open question (Gächter and Riedl 2006). This proposal should be explained.

Would you propose as fair a distribution that is different from those presented previously? If so, please answer the following questions:

- How would you distribute the €75,000 available in situation A?

- How would you distribute the €45,000 available in situation B?

- If you have proposed a new distribution, what criterion have you used?

Fourthly, among all the fair proposals, the respondent must select which is the fairest proposal.

Considering all the previous pairs of distributions that you think are fair, which one do you think is the “fairest”?

Finally, the questionnaire concludes by asking a battery of personal and socio-economic questions.

4 Results

It is noteworthy that throughout this section, the p-values correspond to the null hypotheses that the percentages are equal either for all the contexts or for all the personal characteristics of the respondents, and comments refer to a significance level equal to or greater than 10%.

Regarding the sample, the total nomber of respondents is 575. The global results are shown in Fig. 2. Among all the proposed rules, the P rule is considered the fairest rule by the highest percentage of respondents, 65.32%, whereas the CEL rule is considered the fairest rule by the lowest percentage of respondents, 4.95%. Moreover, summing up the answers to the open question “Others”, 87 respondents, 12.48%, propose an allocation criterion that is different from the provided rules. Approximately, one third of them indicate that a minimum amount should be given to everyone, allocating the remaining amount using a criterion such as the P, CEA, CEL or T rules.

4.1 Influence of contexts

Of the completed questionnaires, 290 correspond to the firm versions and 285 to the mutual benefit society versions. Table 6 in Appendix 2 reports the sample sizes of each of the different contexts, which vary between 64 and 80.

Table 2 shows the percentages of respondents that consider a rule the fairest proposal for the different questionnaires. For all the contexts, the P rule is chosen by the largest number of respondents (between 52.70 and 71.74%). Comparing the CEL and CEA rules, the former is considered the fairest rule by a smaller percentage of respondents than the second one. Moreover, the CEL rule has the largest degree of variability.

Next, we study the differences among the distributions of the fairest rule for each pair of contexts using the Fisher exact test (see Table 3).

When we consider only a change in the background story, that is, firm versus benefit society, there are no significant differences. Similarly, only changing the levels of wealth, as measured by other sources of income, does not significantly affect the respondents’ answers.

However, a change in the origin of the claims, that is, skills versus efforts, leads to significant differences in the distributions of the fairest rule for benefit societies when the agents have no other sources of income (MSN and MEN). In MSN, the claims are due to family situations so they represent needs, whereas in MEN, the claims come from monetary contributions. As Table 2 shows, the percentage of respondents that think the P rule is the fairest proposal is lower in MSN, 52.7%, than in MEN, 71.6%. In contrast, the percentages of respondents who select any other rule (CEA, CEL or T) as the fairest rule are greater in MSN than in MEN. Specifically, these percentages increase by 43.3% for the CEA rule, by 200% for the CEL rule and by 533.3% for the T rule. Therefore, the appeal of the proportionality principle wanes when needs are at the root of the claims.

These same qualitative changes are observed when comparing MSN–FEN, MSY–FEN and MSN–MEY for which there are also significant differences in the distributions of the fairest rule. It is noteworthy that according to Table 2, in MSN–FEN and MSY–FEN the CEL rule goes from 0% in FEN to 13.5% and 6.8% in MSN and MSY, respectively. Furthermore, the changes in the distributions of MSY-FEN are smoother than those of MSN–FEN. The largest increase in the percentage of respondents who think that the CEA rule is the fairest comes from the comparison of the FSY and MSN contexts, while the largest increase in the percentage of respondents who think that the T rule is the fairest occurs between the MEN and FSY contexts.

Finally, regarding the distributions of the fairest rule in MSN–FSY, which also show significant differences, the percentages of respondents who think the P or T rules are the fairest are lower in the MSN context, 52.7% and 9.5%, respectively, than in FSY, 64.2% and 10.4%, respectively. However, the percentages of respondents who selected the CEA or CEL rules as the fairest proposal are larger in MSN than in FSY. Specifically, these percentages increase by 231.1% for the CEA rule and by 200% for the CEL rule.

From the previous analysis we can say that, generally speaking, the main differences in the fairest rule appear when comparing the context in which claims represent needs and people do not have another source of income (MSN) with other contexts. Note that in MSN, the CEA, CEL and T rules have been selected by a larger share of the respondents who abandon the principle of proportionality. Some of these respondents probably think that the fairest allocation should benefit all the needy in the same way. The CEA rule does this, providing the same amount to all claimants irrespective of their needs. Others believe that the fairest allocation should benefit all the needy in a way that the needs not met are the same. The CEL rule does this, equalising the sacrifice that all claimants will have to make. The respondents who selected the T rule think that the fairest allocation should combine the two previous ideas, benefit all the needy in the same way up to a certain point and, having reached it, equalise the needs not met.

Therefore, our results identify some contextual root causes of differences in perceptions of justice on conflicting claims problems, complementing previous works closer to our own. Indeed, according to Bosmans and Schokkaert (2009), for both the pensions and the firm version, the P rule very well describes respondents’ choices, as it does in this paper. Moreover, their responses in the pensions version are more equal than in the company version. This contrasts with our results since, as shown in Table 2, this only occurs when the claims represent needs and talent, respectively, (FSN–MSN) but the opposite is observed for the rest of the pairs, where the percentage of respondents choosing proportionality is larger for the pensions version than for the firm version, FSY–MSY, FEN–MEN and FEY–MEY. The pair with the biggest difference in this respect is FEY–MEY, with 61% and 69% of respondents choosing the P rule, respectively.

4.2 Influence of personal characteristics

Among all the respondents’ personal characteristics, we have focused on whether there are different answers according to employment status, education level, year of birth and gender. Table 7 in Appendix 2 summarises the number of responses collected for each category. Other characteristics we requested did not have enough answers to ensure significant analysis. To find a relation between personal characteristics and the probability of the responses to the different rules, a set of probit models has been run. Specifically, we used the probability of considering each rule the fairest as the dependant variable (Tables 4 and 5). We included the personal characteristics as dummy variables to differentiate between contexts (firm vs. mutual benefit society, efforts vs. skills and extra income vs. no extra income). Table 4 summarises the results for the probit coefficients, and Table 5 shows the results for the probit marginal effects. Since we used a probit regression with dummy variables to properly interpret the model coefficients, it is better to consider the probit marginal effects. They represent the partial effects for the average observation. That is, the other variables are set at their mean, and the effect is calculated, as explained by Scott Long (1997) and Hoetker (2007), which can also be interpreted as calculating the partial effect for the average individual in the sample, following Greene (2011). The marginal effects provided in Table 5 correspond to the values obtained in this way.

Firstly, according to Table 5, only education levels have a significant effect on the choice of the CEA rule as the fairest proposal. Specifically, having completed secondary school, compared to primary school, decreases the probability of selecting the CEA rule by 10.2 percentage points (pp). The same effect occurs for graduates and postgraduates when compared to those who have completed primary education, with decreases in 10.5 and 17.6 pp, respectively. Education levels also have significant effects on the choice of the P rule as the fairest. In this case, having completed a postgraduate degree compared to finishing primary school increases the probability of selecting the P rule by 19.9 pp. It is possible that people with higher education levels are more aware of the efforts needed to acquire it (time, money, etc.) and therefore base their choice on the principle of meritocracy: “to each one what they deserve”, which implies abandoning the equal awards criterion as the fairest distribution in favour of the proportional criterion.

Secondly, the age of the respondents has significant effects on the choice of both the P and CEL rules as the fairest proposal. A very small increase in age increases the probability of selecting the P rule by 0.7% and decreases the probability of selecting the CEL rule by 0.3%.

Thirdly, employment status only has effects on the choice of the CEL rule as the fairest rule. Being a salaried worker instead of a student increases the probability of selecting the CEL rule by 4.8 pp.

Fourthly, the probability of selecting the Talmud rule as the fairest is influenced by none of the considered personal characteristics of the respondents.

Finally, gender has no effect on the choice of any of the rules as the fairest proposal.

The information given above illustrates that as in other contexts, personal characteristics might influence perceptions of fairness in conflicting claims problems. Our results for gender and education may be surprising or contradictory to some studies in different contexts (see, for example, Cohn et al. 2021 and Croson and Gneezy 2009), but what they indicate is that this issue should be analysed in depth-with questionnaires designed exclusively for this purpose.

4.3 Additional remarks

It is worth mentioning that according to the estimations of these probit models, we find that the origin of the claims has significant effects on the choice of the CEL rule as the fairest. Specifically, considering claims that represent efforts compared to skills decreases the probability of selecting the CEL rule by 2.6 pp.

Note also that 64 respondents, 11.13% of the sample, do not consider themselves to be supportive people. Most of these respondents (76.6%) are men, 25% of whom were born between 1971 and 1980. These percentages should be treated with caution because they must be compared with the proportions of these people in the whole sample. They make up 59% and 19.7% of the sample, respectively, with no significant differences related to education levels or employment status.

5 Conclusions

We focus on empirical social choice, using a questionnaire on conflicting claims problems to analyse whether the response patterns of society when facing these situations depend on the economic context. Next, we present the main conclusions obtained from our study.

Firstly, similar to all the previous studies, our analysis confirms that the P rule is the fairest allocation for most people, with 65.32%.

Secondly, and contrary to previous studies, an isolated change either in the background story or additional sources of income does not cause any significant differences in the respondents’ fairness criterion.

Thirdly, the origin of the claims leads to significant differences in the fairest rule. As previously mentioned, when comparing the context in which claims represent needs and people do not have another source of income (MSN) with other contexts, the CEA, CEL and T rules are selected by a larger share of the respondents who abandon the principle of proportionality. Furthermore, considering claims that represent efforts compared to skills, decreases the probability of selecting the CEL rule.

Fourthly, there are significant differences in the response patterns related to the following personal characteristics of the respondents: employment status, education level and year of birth. Therefore, the analysis of distributive justice perceptions in a society would not be sufficiently representative if respondents were recruited from a homogeneous subgroup of the population, such as undergraduate students, as is usually the case.

Finally, the respondents’ choices give some insights into the concept of solidarity and guaranteeing basic needs. Concretely, the data show a tendency to focus on people’s sacrifices when rights represent needs. Moreover, we can detect concern about ensuring that people can meet their basic needs, but not in all the economic contexts in which agents do not have enough resources. Nonetheless, we have not reached any clear conclusion concerning these two aspects. As discussed in Sect. 2, we can infer that the choice of the P rule prioritises that the allocation should not depend on the way the agents face the problem: gains and losses (self-duality). The choice of the CEA rule implies that it can easily be reapplied if the endowment is increased, taking into account only the added endowment (composition up). The CEL rule can easily be reapplied under a decrease in the endowment (composition down), and it does not change once a minimum amount is allocated to each agent (minimal rights first). Finally, the choice of the T rule is egalitarian when the endowment is small, does not change once a minimum amount is allocated to each agent (minimal rights first), and it prioritises neither the gains nor the losses points of view (self-duality).

Notes

Quotas ended on 1 April 2015.

See the “Final Report of the Special Master for the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund of 2001”.

Specifically, Chapter 4 of Gaertner and Schokkaert (2012) summarises the empirical works related to conflicting claims problems.

Yaari and Bar-Hillel (1984) concentrate on pure distribution problems.

Bosmans and Schokkaert (2009) also analyse within-context consistency, that is, for a given economic context, to what degree do people use the same rule for claims problems with different claims vectors and/or endowments.

See Thomson (2019) for further details and a comprehensive study of equity principles and their implications.

For technical details about these properties, we refer to Thomson (2019), among others.

References

Amiel Y, Cowell F, Gaertner W (2008) To be or not to be involved: a questionnaire-experimental view on Harsanyis utilitarian ethics. Soc Choice Welfare 32(2):299–316

Aumann RJ, Maschler M (1985) Game theoretic analysis of a bankruptcy from the Talmud. J Econ Theory 36:195–213

Bosmans K, Lauwers L (2011) Lorenz comparisons of nine rules for the adjudication of conflicting claims. Internat J Game Theory 40(4):791–807

Bosmans K, Schokkaert E (2009) Equality preference in the claims problem: a questionnaire study of cuts in earnings and pensions. Soc Choice Welfare 33(4):533–557

Büyükboyacı M, Gürdal MY, Kıbrıs A, Kıbrıs Ö (2019) An experimental study of the investment implications of bankruptcy laws. J Econ Behav Organ 158:607–629

Cappelen AW, Luttens RI, Sørensen EØ, Tungodden B (2019) Fairness in bankruptcies: an experimental study. Manage Sci 65(6):2832–2841

Cohn A, Jessen LJ, Klasnja M, Smeets P (2021) Why do the rich oppose redistribution? An experiment with america’s top 5%. SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=3395213

Croson R, Gneezy U (2009) Gender differences in preferences. J Econ Literat 47(2):448–74

Curiel J, Maschler M, Tijs S (1987) Bankruptcy games. Z Oper Res 31:A143–A159

Dagan N (1996) New characterizations of old bankruptcy rules. Soc Choice Welfare 13(1):51–59

Gächter S, Riedl A (2006) Dividing justly in bargaining problems with claims. Soc Choice Welfare 27(3):571–594

Gaertner W, Schokkaert E (2012) Empirical social choice: questionnaire-experimental studies on distributive justice. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Gaertner W, Schwettmann L (2017) Burden sharing in deficit countries: a questionnaire-experimental investigation. SERIEs 8(2):113–144

Gaertner W, Bradley R, Xu Y, Schwettmann L (2019) Against the proportionality principle: experimental findings on bargaining over losses. PLoS ONE 14(7):e0218805

Gallastegui M, Iñarra E, Prellezo R (2003) Bankruptcy of fishing resources: The northern European anglerfish fishery. Mar Resour Econ 17:291–307

Gantner A, Horn K, Kerschbamer R (2019) The role of communication in fair division with subjective claims. J Econ Behav Organ 167:72–89

Giménez-Gómez J-M, Teixidó-Figueras J, Vilella C (2016) The global carbon budget: a conflicting claims problem. Clim Change 136(3–4):693–703

Greene WH (2011) Econometric analysis, 7th edn. Vol. Pearson series in economics. Pearson Education

Hegtvedt KA, Cook KS (2001) Distributive justice: recent theoretical developments and applications. In: Sanders J, Hamilton VL (eds) Handbook of justice research in law. Kluwer Academic Publishers, New York, pp 93–132

Herrero C, Moreno-Ternero JD, Ponti G (2010) On the adjudication of conflicting claims: an experimental study. Soc Choice Welfare 34:145–179

Hoetker G (2007) The use of logit and probit models in strategic management research: critical issues. Strateg Manag J 28(4):331–343

Hougaard JL, Østerdal LP (2005) Inequality preserving rationing. Econ Lett 87(3):355–360

Hougaard JL, Moreno-Ternero J, Østerdal LP (2012) A unifying framework for the problem of adjudicating conflicting claims. J Math Econ 48:107–114

Iñarra E, Skonhof A (2008) Restoring a fish stock: a dynamic bankruptcy problem. Land Econ 84(2):327–339

Ju B-G, Moreno-Ternero JD (2008) On the equivalence between progressive taxation and inequality reduction. Soc Choice Welfare 30(4):561–569

Kalai E (1977) Proportional solutions to bargaining situations: interpersonal utility comparisons. Econ J Econ Soc 1623–1630

Kasajima Y, Velez RA (2010) Non-proportional inequality preservation in gains and losses. J Math Econ 46(6):1079–1092

Kittel B, Kanitsar G, Traub S (2017) Knowledge, power, and self-interest. J Public Econ 150:39–52

Lucas-Estañ M, Gozalvez J, Sanchez-Soriano J (2012) Bankruptcy-based radio resource management for multimedia mobile networks. Trans Emerg Telecommun Technol 23:186–201

Moreno-Ternero JD, Roemer JE (2012) A common ground for resource and welfare egalitarianism. Games Econom Behav 2(75):832–841

Moreno-Ternero JD, Villar A (2006) On the relative equitability of a family of taxation rules. J Public Econ Theory 8(2):283–291

Moulin H (2000) Priority rules and other asymmetric rationing methods. Econometrica 68(3):643–684

Nozick R (1974) Anarchy, state and utopia. New York basic book

O’Neill B (1982) A problem of rights arbitration from the Talmud. Math Soc Sci 2(4):345–371

Schokkaert E, Capeau B (1991) Interindividual differences in opinions about distributive justice. Kyklos 44(3):325–345

Schokkaert E, Overlaet B (1989) Moral Intuitions and economic models of distributive justice. Soc Choice Welfare 6:19–31

Scott Long J (1997) Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Adv Quant Techn Soc Sci 7

Sen A (1973) On economic inequality. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Tarroux B (2019) The value of tax progressivity: evidence from survey experiments. J Public Econ 179:104068

Thomson W (2012) Lorenz rankings of rules for the adjudication of conflicting claims. Econ Theor 50(3):547–569

Thomson W (2015) Axiomatic and game-theoretic analysis of bankruptcy and taxation problems: an update. Math Soc Sci 74:41–59

Thomson W (2019) How to divide when there isnt enough, vol 62. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Timoner P, Izquierdo JM (2016) Rationing problems with ex-ante conditions. Math Soc Sci 79:46–52

Widerquist K, Noguera JA, Vanderborght Y, De Wispelaere JE (2013) Basic income: an anthology of contemporary research. Wiley-Blackwell, Cambridge

Yaari ME, Bar-Hillel M (1984) On dividing justly. Soc Choice Welfare 1(1):1–24

Young P (1987) On dividing an amount according to individual claims or liabilities. Math Oper Res 12:198–414

Young P (1988) Distributive justice in taxation. J Econ Theory 43:321–335

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply grateful to all the respondents. Pedro A. Gadea-Blanco, who collaborated actively in the design of the questionnaires, is also acknowledged. We also convey thanks to all the colleagues who helped us to distribute our questionnaires among different institutions, for instance, the Fundación Española para la Ciencia y la Tecnología (FECYT), the Faculty of Business of the Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena, the Cloud Incubator Hub, the interuniversitary PhD program DecIdE, the Spanish Network of Social Choice (REES), and the Research Centre on Economics and Sustainability (ECO-SOS). The usual caveats apply. For their suggestions we also thank the seminar participants at the WIPE. Financial support from Universitat Rovira i Virgili and Generalitat de Catalunya (2017PFR-URV-B2-53 and 2017 SGR 770) and Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (ID2019-105982GB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, PID2020-119152GB-I00ECO2016-75410-P (AEI/FEDER, UE) and ECO2016-77200-P) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Questionnaires

As commented, we have eight different types of questionnaires. In this section, we provide the questionnaires. Due to the fact that the body of each questionnaire is similar, only changing in context, next we introduce the first class of them, and we establish the differences in each context (see also Fig. 1).

Previous to the questionnaire itself, the following text was displayed providing general information about the process:

Research study: opinion poll

How to distribute when there is not enough?

Introduction: We have to distribute an amount of money among several individuals and their rights are superior to the available quantity. How should we distribute it?

This opinion poll deals with the analysis of the acceptance and evaluation, by the society, of different forms of distributing for this type of problems.

Please note that it is about your personal opinion, therefore there are not “right” or “wrong” answers.

The questionnaire is completely anonymous.

Thank you very much for devoting your time to answer this questionnaire.

Questionnaire FEN

1.1 Context

The advertising department of a private company placed in Spain consists of three people with the following characteristics:

-

Same qualification level

-

Similar family situation

-

Same creative ability

-

None of them has another source of income

-

All of them live in Spain

The company committed to pay them €120,000 per year, an amount that it was decided to distribute according to the number of hours worked by each of them as follows: (30,000; 39,000; 51,000). That is:

-

Publicist 1: €30,000

-

Publicist 2: €39,000

-

Publicist 3: €51,000

However, due to causes beyond the control of the workers, the amount of money the company can spend this year on their salaries is lower, and this is the reason why the acquired rights cannot be met fully.

Consider the following two situations:

-

A)

The company has only €75,000.

-

B)

The company has only €45,000.

1.2 Distributions

Next, different distributions for situations A and B are proposed.

We want to know if you consider them fair or not. Note that you can select more than one option as fair.

Moreover, if you select a pair of distributions as fair, it means that you think that the distributions proposed for both situations, A and B, are fair simultaneously.

1.2.1 Distribution 1

The available amount of money is equally divided among the three publicists.

-

In situation A the distribution would be (25,000; 25,000; 25,000).

-

In situation B the distribution would be (15,000; 15,000; 15,000).

Do you think this pair of distributions is fair?

-

Yes

-

No

1.2.2 Distribution 2

The three publicists lose the same amount of money.

-

In situation A, the distribution would be (15,000; 24,000; 36,000), because everyone loses €15,000.

-

In situation B, the distribution would be (5000; 14,000; 26,000), because everyone loses €25,000.

Do you think this pair of distributions is fair?

-

Yes

-

No

1.2.3 Distribution 3

If the available amount of money is greater than half of the originally committed amount (greater than €60,000), then the money is distributed so that each publicist loses the same amount (Distribution 2). If the available amount of money is less than half of the originally committed amount (less than €60,000), then the money is equally divided among publicists (Distribution 1).

-

In situation A the distribution would be (15,000; 24,000; 36,000), because everyone loses €15,000.

-

In situation B the distribution would be (15,000; 15,000; 15,000).

Do you think this pair of distributions is fair?

-

Yes

-

No

1.2.4 Distribution 4

The percentages of money that correspond to each publicist according to the original commitment are 25%, 32.5% and 42.5%, respectively. The final available amount is distributed using these percentages.

-

In situation A, the distribution would be (18,750; 24,375; 31,875).

-

In situation B, the distribution would be (11,250; 14,625; 19,125).

Do you think this pair of distributions is fair?

-

Yes

-

No

1.2.5 Distribution 5

Would you propose as fair a distribution that is different from those presented previously? If so, please answer the following questions:

-

How would you distribute the €75,000 available in situation A?

-

How would you distribute the €45,000 available in situation B?

-

If you have proposed a new distribution, what criterion have you used?

1.2.6 The “fairest” distribution

Considering all the previous pair of distributions that you think are fair, which one do you think is the “fairest”?

-

Distribution 1

-

Distribution 2

-

Distribution 3

-

Distribution 4

-

Distribution 5

1.3 Personal characteristics

Please, answer the following questions:

1.3.1 Gender

-

Male

-

Female

1.3.2 Year of birthday

1.3.3 Highest level of education completed

-

Uneducated

-

Primary or compulsory education

-

Secondary or bachelor’s degree

-

Graduate

-

Postgraduate (Master or Doctorate)

1.3.4 Approximate level of household income (yearly)

-

Below €15,000 (about $19,500)

-

Between €15,000 and €35,000 (about, between $19,500 and $45,500)

-

Between €35,000 and €50,000 (about, between $45,500 and $65,000)

-

Above €50,000 (about $65,000)

1.3.5 What is the number of people in your family (including yourself)?

1.3.6 Employment status

-

Student

-

Retiree

-

Worker

-

Self-employed

-

Other

1.3.7 If you have selected “Other” in previous question, write it down

1.3.8 Occupation

1.3.9 City and country of birth

1.3.10 City and country of habitual residence

1.3.11 Do you consider yourself a supportive person?

-

Yes

-

No

Thank you very much for your collaboration

If you want, you can next make any comments about this questionnaire.

1.3.12 Comments

Questionnaire FEY

1.1 Context

The advertising department of a private company placed in Spain consists of three people with the following characteristics:

-

Same qualification level

-

Similar family situation

-

Same creative ability

-

All of them have, in addition to the salary, other sources of income that allow them to cover their basic needs

-

All of them live in Spain

The company committed to pay them €120,000 a year, an amount that it was decided to distribute according to the number of hours worked by each of them...

Questionnaire FSN

1.1 Context

The advertising department of a private company placed in Spain consists of three people with the following characteristics:

-

Same qualification level

-

Similar family situation

-

All of them work the same number of hours

-

None of them has another source of income

-

All of them live in Spain

The company committed to pay them €120,000 a year, an amount that it was decided to distribute according to their creative abilities...

Questionnaire FSY

1.1 Context

The advertising department of a private company placed in Spain consists of three people with the following characteristics:

-

Same qualification level

-

Similar family situation

-

All of them work the same number of hours

-

All of them have, in addition to the salary, other sources of income that allow them to cover their basic needs

-

All of them live in Spain

The company committed to pay them €120,000 a year, an amount that it was decided to distribute according to their creative abilities...

Questionnaire MEN

1.1 Context

Three people are members of a mutual benefit society that operates in Spain. They have paid to such a society in order to receive a retirement pension. When retiring, they have the following characteristics:

-

Similar family situation

-

None of them has another source of income

-

All of them live in Spain

All together, are entitled to receive €120,000 a year, an amount that it was decided to distribute according to the payments made by each of them...

Questionnaire MEY

1.1 Context

Three people are members of a mutual benefit society that operates in Spain. They have paid to such a society in order to receive a retirement pension. When retiring, they have the following characteristics:

-

Similar family situation

-

All of them have, in addition to the retirement pension, other sources of income that allow them to cover their basic needs

-

All of them live in Spain

All together, are entitled to receive €120,000 a year, an amount that it was decided to distribute according to the payments made by each of them...

Questionnaire MSN

1.1 Context

Three people are members of a mutual benefit society that operates in Spain. They have paid such a society in order to receive a retirement pension. When retiring, they have the following characteristics:

-

All of them have paid to the society the same amount of money

-

None of them has another source of income

-

All of them live in Spain

All together, are entitled to receive €120,000 a year, an amount that it was decided to distribute according to the family situation of each of them...

Questionnaire MSY

1.1 Context

Three people are members of a mutual benefit society that operates in Spain. They have paid to such a society in order to receive a retirement pension. When retiring, they have the following characteristics:

-

All of them have paid to the society the same amount of money

-

All of them have, in addition to the retirement pension, other sources of income that allow them to cover their basic needs

-

All of them live in Spain

All together, are entitled to receive €120,000 a year, an amount that it was decided to distribute according to the family situation of each of them...

Appendix 2: Sample sizes

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Giménez-Gómez, JM., Carmen Marco-Gil, M. & Sánchez-García, JF. New empirical insights into conflicting claims problems. SERIEs 13, 709–738 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-022-00265-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-022-00265-9