Abstract

Genetic variation of 36 Sechium edule accessions collected across 12 states in India was assessed using morphological traits and DAMD markers. Eighteen fruit morphological traits (both qualitative and quantitative) were evaluated to confirm the variations in the present collection. Quantitative traits showed major variations with respect to fruit weight (7.85–498.33 g/fruit), fruit length (5.8–15 cm/fruit), fruit diameter (6–28 cm/fruit) and length of the spine (0–5 cm). Qualitative traits were also diverse in fruit colour, shape, spine density, reticulation, flexibility of spine and furrow depth. The first six principle components showed 82.88% variation in the principal component analysis. The principal component analysis revealed that fruit weight, fruit width, fruit diameter, fruit shape, length of spine, spine density and furrow depth had a significant contribution to the total variation. The DNA analysis performed using DAMD primers were used for deducing the diversity at DNA level. The collection produced 102 bands out of which 97 were polymorphic and the percentage polymorphism ranged between 66.66 and 100 per primer. Discrete pattern of clustering was obtained using UPGMA method of complete linkage percent disagreement revealing high diversity among the collected accessions. Thus, the present study indicates that molecular and morphological marker map would improve our knowledge of S. edule and would facilitate efforts to breed improved S. edule cultivars.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

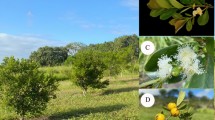

Sechium edule (Jacq.) Swartz (Chayote or air potato) is one of the neglected vegetable crops and belongs to the family Cucurbitaceae. It is an herbaceous, perennial, monoecious climber and is now considered as an important food in tropical and subtropical regions of the world (Morton 1981). The wild species of S. edule and the related species are abundantly found in Central America and Mexico, and is the center of origin. The close relatives, S. compositum, S. hintonii and S. tacaco are either endemic or restricted to their original area. Sechium edule was introduced in India where it grows widely in the South and North-Eastern parts of India (Newstrom 1991). The shoots, stems, leaves and tuberous roots are edible and the fruits are now being consumed in many countries as it has been reported to have anti-diabetic (Maity et al. 2013), antimicrobial (Ordonez et al. 2003), anti ulcer (Sateesh et al. 2012) and antihypertensive activities (Earl et al. 2014).

Sechium edule fruit displays a great diversity of size, shape, fruit wall features and texture (Lira-Saade 1996). Such collection of germplasm and characterization forms an essential stage of crop improvement and breeding programs. Morphological traits are essential for preliminary evaluation and for assessment of genetic diversity as S. edule fruits are the sign of its diversity. Without determining the diversity, it would be difficult to determine the associated qualitative traits (Lansari et al. 1994).

The precocious germination of the S. edule hinders the efforts to conserve and study these resources and the conservation using simple orthodox methods cannot be carried out (Esquivel and Engelmann 2002). Therefore, it has to be subjected to field gene banks, which turns out to be an expensive procedure. The wider population of S. edule varieties was not studied or classified systematically until the beginning of the 1980s (Engels 1983). The factors like frost, drought and root diseases led to the decline of the collections gradually. A total number of 375 accessions grown in Costa Rica, Honduras and Guatemala were reduced to almost half by 1981 due to such environmental factors (Newstrom 1986). Similar decline in the number of accessions were observed among the Mexican collections. As a wide diversity is seen among S. edule populations in India, both morphological and molecular data are essential and these form a backbone for the conservation of genetic resources for present and future use (Sanwal et al. 2010).

Advancement in field of molecular biology has led to the concise classification of plant genetic resources. Molecular markers can be used for identifying collections, screen its germplasm or genetic diversity and also resolving the taxonomic relationships (Kameswara 2004). DAMD markers are advantageous as they are highly polymorphic. Cucumber (Hu et al. 2010), Capsicum spp. (Ince et al. 2009), grapevine cultivars (Seyedimoradi et al. 2012) and mulberry species (Bhattacharya and Ranade 2001) have been evaluated successfully for its diversity studies, but no information is available to compare the morphological and genetic studies of S. edule species in India. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to analyze the morphological and genetic variations of S. edule collections from different growing locations across India.

Materials and methods

Collection of plant material and data collection

The fruits for the investigation comprised of 36 S. edule accessions collected from 12 S. edule growing states across India. An initial attempt to grow the plants in uniform field collections was not successful as the collections from the North-Eastern regions of India failed to germinate and we had to continue our studies only with the fruit-related traits. These fruit collections were maintained at −80 °C at Jain University—CPGS campus, Bangalore, India. Eighteen qualitative and quantitative characteristics were recorded for the fruit-related trait as mentioned by Newstrom (1986) and Engels (1983). The traits include shape of the fruits (FS), color (FC), length (FL), width (FW), diameter (FD), weight (W), density of the spines present over the fruits (SD), longitudinal furrow depth (LFD), reticulation (R), cross section profile (CSP), spine length (LS) and spine distribution (SPD) (Table 1) were used in the present investigation.

Molecular characterization

DNA extraction

Total genomic DNA was extracted from the frozen fruit rind of all the 36 accessions by CTAB method (Jain et al. 2015). The total DNA pellet after purification was subjected to RNase treatment at 37 °C. DNA quantification, as well as quality assessment, was carried out spectrophotometrically (A260/280) and similarly the purity of DNA was calculated (Asish et al. 2010). The samples were then stored at −20 °C and aliquots were maintained at 4 °C. A total of 12 DAMD primers were used to screen and amplify the genomic DNA of 36 accessions of S. edule (Hu et al. 2010). PCR amplification was performed in 25 µl of the reaction mixture containing 25 ng sample DNA, 1 mM dNTP, 10 pM primer and 2 units Taq polymerase with 2.5 µl of PCR buffer containing 15 mM MgCl2 per reaction. The temperature profile was as follows: 94 °C for 4 min, followed by 40 cycles at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing temperature (50–61 °C) for 1 min, 72 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 5 min final extension. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis through 1.2% agarose gel and the profiles were analyzed (Hu et al. 2010). The presence and absence of bands were recorded; the binary data generated was used to estimate the level of polymorphism using UPGMA.

Statistical analysis

The phenotypic data were used for the assessment of morphological characteristics by principal component analysis (PCA) to define the Eigen values using a multivariate analysis program (Unscrambler X, CAMO, Bangalore, Karnataka, India). Similarly, a statistical software package (Statistica) was used to evaluate the correlations between the characteristics and a dendrogram was created by complete linkage percent disagreement using UPGMA method (Manohar and Murthy 2012).

Results

Morphological variation

Thirty six accessions were evaluated for fruit morphological variations using external fruit characters of S. edule. Eighteen qualitative and quantitative characteristics were used as descriptors as per Engels (1983) and Newstrom (1986) listed in the Table 1. A large variation among the collected accessions was observed in case of fruit color, its shape, size and spine density. Among all, 17 accessions were found to be ovoid in shape followed by 13 accessions of subpyriform shape. The length of the fruit varied from 5.8 to 15 cm and the maximum weight recorded was 498.33 g with a minimum of 7.85 g. The color of the fruit varied from dark green to white. Variations were also observed in case of furrows and ridges. Cumulative variations of the quantitative characters were calculated as shown in the Table 2. The maximum cumulative variation is shown in case of length of spines, i.e., 100%. Principal component analysis was used to access the variability in S. edule accessions. The percentage of variation explained by the first six components was as follows: 30, 20, 11, 9, 8 and 6. Eigen vectors that delineated the accessions into separate groups in the first six components are represented in the Table 3.

The fruit shape, length, weight, spine density and longitudinal furrow depth were the important characters for the formation of different clusters. Figure 1 depicts the formation of five clusters with one un-clustered S. edule accession. By these components, first cluster had majority of the accessions from diverse locations (Sikkim, Assam, Meghalaya, Manipur, West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu) having fruit length of 6.5–14 cm and no or very low spine density and majorly having intermediate furrow depth.

Two accessions from Manipur and West Bengal were grouped into another cluster (2). These two accessions were green in color, had no spines and bearing very deep longitudinal furrow depth. Similarly, cluster (3) had collections from Sikkim, Meghalaya, Manipur, Mizoram, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. The fruit length among these collections ranged from 11.5 to 13.5 cm having low to intermediate spine density. The spines spreads across the entire surface of the fruit except for the collection from Meghalaya, with the fruits bearing long/total length furrows for most of them.

Cluster (4) had a similar number of collections from different locations, i.e., Assam, Manipur, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala. These collections were mostly subpyriform or ovoid in nature. These were large in size and the length of the fruit was ranging from 12 to 15 cm. The weight of these fruits ranged from 234.16 to 440.86 g having spines mostly covering entire plant and furrows being long and total length. Cluster (5) had three collections from Sikkim and Manipur. The shape of the fruits was more or less ovoid or round. These three fruits had a very high or an intermediate spine density bearing a very superficial longitudinal furrow depth.

The un-clustered landrace, collected from Sikkim had a length of 5.8 cm and was the tiniest among the collections. It weighs 7.85 g having very low spine density. The minimum, maximum and the mean values to express the range of variability are presented in Table 2.

Genetic diversity and cluster analysis based on DAMD

In the present study, 12 minisatellite core sequences primers were screened among 36 accessions for scoring the amplified DNA sample and to reveal genetic variability of S. edule accessions (Table 4). By optimizing annealing temperature for amplification, each of the primers produced distinct banding patterns with good reproducibility and resolutions. All primers were capable to amplify polymorphic bands. A total of 102 bands were obtained out of which 97 were polymorphic and the average percentage polymorphism of the bands was found to be 95.09%. Eight primers gave 100% polymorphism (URP2F, URP25F, URP38F, HVR (−), OGRBO1, M13, 14C2 and HBV5). The DAMD profile obtained with primer 14C2 is given in the Fig. 2. The percentage polymorphism ranged from 66.66 to 100 and the lowest was recorded for URP1F indicating that DAMD primers could be used to access the genetic variations for S. edule accessions.

The dendrogram, resulting from the complete linkage percent disagreement using UPGMA method, revealed that 36 accessions were grouped into three major clusters Fig. 3. First cluster had 13 accessions from NE India (Sikkim, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, West Bengal, Chhattisgarh and Assam) with more or less superficial or intermediate furrow depth. Accession SEC-28 and SEC-2 is distinct from the group belonging from Karnataka and Sikkim being ovoid in shape and having no spines. The second cluster also had 13 accessions from South India (Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Kerala) with one accession SEC-9 from Meghalaya being similar to these accessions. All accessions had long total length furrows except the accession SEC-30 having short distal. Cluster three forms a group of accessions belonging from Manipur having a linkage distance of 0.3. The fruit length was above 8.5 and fruit weight was above 175 g. These accessions had very low or intermediate or no spines bearing fruits. The maximum linkage distance obtained was 0.4. Thus, the present study indicates that the DAMD makers can be efficiently used to characterize S. edule accessions.

Discussion

India is rich in S. edule genetic resources and the identification or utilization of these diverse germplasm is the central criteria in plant breeding. Thorough knowledge and understanding can provide a platform for accurate assessment of plant cultivars. Analysis of genetic diversity can assist in reliable classification of collections required for crop improvement (Mohammadi and Prasanna 2003; Manohar and Murthy 2012). Morphological analysis has been used for characterizing large data sets and such description has become a valuable source of information for agronomic and breeding programs (Boczkowska et al. 2014). In the present study, the morphological classification of 36 accessions revealed a great diversity in fruit morphological traits across India. The first six components give a total variation of 84%. The characters with such high variability will be expected to provide high level of gene availability for transfer during the breeding programs (Aliyu et al. 2000). The maximum variation was seen in case of length of spines followed by weight of the fruit, with prominent variations in color, size, shape and presence of furrows. The presence of spines was attributed to the lower amounts of gibberellic acid as demonstrated by Cadena-Iniguez (2005) in an experiment where the application of gibberellic acid promoted spine development to the fruits showing certain level of dependency over hormones.

The fruits collected in the present study had a maximum weight of 498.33 g and a minimum of 7.85 g and the fruit length varied from 5.8 to 15.0 cm when compared to the collections from Sikkim as observed by Kapoor et al. (2014) (maximum fruit weight of 461 g and a minimum of 74.1 g; maximum fruit length of 8.43–16.76 cm). Similar diversity was observed with that of fruit colour, shape and spine density. Maximum diversity was observed in the present study than that of the Kapoor et al. (2014) as they had concentrated their collection only to Sikkim state of India. Sanwal et al. (2010) observed a similar morphological diversity in the North-Eastern germplasm of India as that of Kapoor et al. (2014) with the length of the fruit (5.70–15.80 cm), diameter (5.2–10.90) and weight (134–406 g) showing maximum variations. In a study conducted by Cadena-Iniguez et al. (2008) fruits of Sechium edule were collected in the central region of Veracruz, Mexico, and classified them under eight groups according to their characteristics. The fruit length varied from 3 to 15 cm which is similar as obtained in the present study. It projected the quantitative, pseudo-qualitative and qualitative characters of leaf flower and fruit depicting morphological and anatomical variations of S. edule and the greatest variation was observed among the cultivated varieties. The variations observed may be due to the environmental and soil conditions (pH 7.3–7.9) and the presence of Ca and Mg can cause physiological stress leading to low levels of chlorophylls and thus evoking color loss of the fruits of the plant (Cadena-Iniguez et al. 2007).

From the present study, it was observed that the maximum diversity of S. edule was concentrated in the North-Eastern India when compared to low diversity in the Southern India. The North-Eastern India has a different set of landraces that does not grow in the planes of Southern India as it grows in high altitude regions of India. This study provides a detailed diversity of the fruit morphology present in India and the same were also observed in the Central American collections (Newstrom 1991). The collections of Costa Rica and Mexico had fruit sized up to 25 cm, which weighed at least 1000 g (Engels 1983). Such huge fruits were not observed in Indian collections.

Even though the morphological characters are generally employed to estimate genetic diversity, such a method has its own limitations as the traits are heavily influenced by the environmental conditions and climate being the main factor influencing the growth and development of the species (Cadena Iniguez and Arevalo Galarza 2011). As a result, the S. edule accessions have also been studied using molecular markers. To have a comprehensive idea of the variability among the S. edule accessions, DAMD analysis was carried out. The results obtained showed a higher percentage of polymorphism, i.e., ranging from 66.66 to 100. Eight primers showed 100% polymorphism, i.e., URP2F, URP25F, URP38F, HVR (−), OGRBO1, M13, 14C2 and HBV5. Four primers were found to have 100% polymorphism as compared to studies conducted by Hu et al. (2010) using DAMD markers for cucumber collections. Avendano‐Arrazate et al. (2012) reported high degree of polymorphism in Mexican accessions of S. edule but such studies was limited to the use of isozyme systems. The high level of percentage polymorphism obtained indicates that DAMD primers can be used for S. edule species to screen its diversity.

The UPGMA method of clustering using complete linkage percent disagreement revealed three clusters. The maximum linkage distance observed was 0.4. The dendrogram obtained showed that all accessions had a discrete pattern of clustering which have been grouped more or less according to their state or geographical distribution. From the above results, North East and South India collections were easily separated suggesting a practicability of using DAMD markers for germplasm identification.

There was less correlation between the divergence of morphological traits and the data obtained using molecular marker which suggests that the morphological variation may be determined by environmental factors and also by genetic factors as reported for other crops (Seyedimoradi et al. 2012; Ashish et al. 2014; Kumar and Nair 2013). It is frequently observed that the genetic variation determined by molecular markers can produce different results due to analysis in different regions in the genome captured by the respective markers. Morphological traits are associated with a relatively small number of specific gene loci; thus, there could be loss of potential difference in the analysis of large amounts molecular data (Diederichsen 2009) suggesting that DAMD markers varied in terms of comparability with morphological traits of S. edule accessions. From a wide variety of colors, shapes and flavors, this species is widely accepted as a regional food across world. Though S. edule has economic, cultural and environmental importance, comprehensively it has not been addressed in research process (Cadena Iniguez and Arevalo Galarza 2010).

There are no reports on the genetic diversity of S. edule accessions using morphological characters and molecular markers so far. This remains the first study using morphological and genetic diversity characterization of S. edule in India and the study reveals a high degree of diversity among the Indian S. edule accessions which can be further used for crop improvement. This may provide an opportunity to enhance and boost the breeding strategy.

In conclusion, the accessions used in the present study showed a wide variation in the morphological characters. All the minisatellite core sequences revealed high level of polymorphism in S. edule accessions. The PCA analysis and phylogenetic data obtained based on DAMD markers generated a specific clustering patterns which revealed geographical variation due to environmental conditions and the three groups obtained in a dendrogram demonstrated the genetic relationship among the germplasm. Such characterization of genetic resources forms an important factor for crop improvement program. It also confirms the importance of molecular studies besides the morphological data in detecting the genetic variation among the diverse accessions to carry out further crossing studies successfully.

References

Aliyu B, Akoroda MO, Padulosi S (2000) Variation within Vigna reticulata Hooke FII Nig. J Gene: 1–8

Ashish K, Singh PK, Rai N, Bhaskar GP, Datta D (2014) Genetic diversity of French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes on the basis of morphological traits and molecular markers. Indian J Biotech 13:207–213

Asish GR, Parthasarathy U, Nithya NG (2010) Standardization of DNA isolation and PCR parameters in Garcinia spp. for RAPD analysis. Indian J Biotechnol 9:424–426

Avendano-Arrazate CH, Cadena-Iniguez J, Arevalo-Galarza ML, Cisneros-Solano VM, Aguirre-Medina JF, Moreno-Perez EC (2012) Variacion genetica en el complejo infraespecifico de chayote evaluada mediante sistemas isoenzimaticos. Pesq Agropec Bras 47(2):244–252

Bhattacharya E, Ranade SA (2001) Molecular distinction amongst varieties of mulberry using RAPD and DAMD profiles. BMC Plant Biol 1:1–8

Boczkowska M, Nowosielski J, Nowosielska D, Podyma W (2014) Assessing genetic diversity in 23 early Polish oat cultivars based on molecular and morphological studies. Genet Resour Crop Evol 61:927–941

Cadena-Iniguez J, Arevalo-Galarza L, Avendano-Arrazate CH, Soto-Hernandez M, Ruiz-posadas LM, Santiago-osorio E, Acosta-Ramos M, Cisneros-Solano VM, Aguirre-Medina JF, Ochoa-Martinez D (2007) Production, genetic, postharvest management and pharmacological characteristics of Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw. Fresh Produce 1(1):41–53

Cadena-Iniguez J, Avendano-Arrazate CH, Soto-Hernandez MS, Posadas-Ruiz LM, Aguirre-Medina JF, Arevalo-Galarza L (2008) Infraspecific variation of Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw. in the state of Veracruz, Mexico. Genet Resour Crop Evol 55:835–847

Cadena Iniguez J (2005) Caracterizacion morfoestructural, fisiologica, quımica y genetica de diferentes tipos de chayote (Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw.). Tesis Doctoral, Colegio de Postgraduados, Texcoco, Mexico, p 156

Cadena Iniguez J, Arevalo Galarza ML (2011) Las Variedades del Chayote Mexicano, Recurso Ancestral con Potencial de Comercializacion. College of Postgraduates Mexico, Grupo Interdisciplinario de Investigacion en Sechium edule en Mexico, AC

Cadena Iniguez J, Arevalo Galarza ML (2010) GISeM: Rescatando y Aprovechando los Recursos Fitogeneticos de Mesoamerica Volumen 1: Chayote. Colegio de Postgraduados, Grupo Interdisciplinario de Investigacion en Sechium edule en Mexico, AC

Diederichsen A (2009) Duplication assessments in Nordic Avena sativa accessions at the Canadian national genebank. Genet Resour Crop Evol 56:587–597

Earl GL, Ramos RR, Zamilpa A, Ruiz MH, Salgado GR, Tortoriello J, Ferrer EJ (2014) Extracts and fractions from edible roots of Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw. with antihypertensive activity. Evid Based Complement Altern Med 2014(1–2):594326

Engels JMM (1983) Variation in Sechium edule in Central America. J Am Soc Hort Sci 7:706–710

Esquivel AA, Engelmann F (2002) Cryopreservation of chayote zygotic embryos and shoot tip from in vitro plantlets. Cryoletters 23:299–308

Hu JB, Li JW, Wang LJ, Liu LJ, Wei S (2010) Utilization of a set of high-polymorphism DAMD markers for genetic analysis of a cucumber germplasm collection. Acta Physiol Plant 11:525–527

Ince AG, Karaca M, Onus AN (2009) Development and utilization of diagnostic DAMD-PCR markers for capsicum accessions. Genet Res Crop Evol 56:211–221

Jain JR, Satyan KB, Manohar SH (2015) Standardization of DNA isolation and RAPD-PCR protocol from Sechium edule. Int J Adv Life Sci 8:359–363

Kameswara RN (2004) Plant genetic resources: advancing conservation and use through biotechnology. Afr J Biotechnol 3:136–145

Kapoor C, Kumar A, Pattanayak A, Gopi R, Kalita H, Avasthe RK, Bihani S (2014) Genetic diversity in local chow-chow (Sechium edule Sw.) germplasm of Sikkim. Indian J Hill Fmg 27(1):228–237

Kumar S, Nair N (2013) Genetic variation and phylogenetic relationships among Indian citrus taxa revealed by DAMD-PCR markers. Genet Resour Crop Evol 60:1777–1800

Lansari A, Iezzoni AF, Kester DE (1994) Morphological variation within collection of Moroccan almond clones and mediterranean and North American cultivars. Euphytica 78:27–41

Lira-Saade R (1996) Chayote, Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw. Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. Report No. 8. Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research, Gatersleben/International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy, p 58

Maity S, Firdous SM, Debnath R (2013) Evaluation of antidiabetic activity of ethanolic extract of Sechium edule fruits in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. World J Pharm Pharm Sci 2(5):3612–3621

Manohar SH, Murthy HN (2012) Estimation of phenotypic divergence in a collection of Cucumis melon, including shelf-life of fruit. Sci Hortic 148:74–82

Mohammadi SA, Prasanna BM (2003) Analysis of genetic diversity in crop plants—salient statistical tools and considerations. Crop Sci 43:1235–1248

Morton JF (1981) The Chayote, a perennial, climbing, subtropical vegetable. In: Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society, Florida, pp 240–245

Newstrom LE (1991) Evidence for the origin of chayote, Sechium edule (Cucurbitaceae). Econ Bot 45:410–428

Newstrom LE (1986) Studies in the origin and evolution of chayote, Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw (Cucurbitaceae). Dissertation, University of California

Ordonez AAL, Gomez JD, Cudmani NM, Vattuone MA, Isla MI (2003) Antimicrobial activity of nine extracts of Sechium edule (Jacq.) Swartz. Microb Ecol Health Dis 15:33–39

Sanwal SK, Singh SK, Singh PK, Misra AK (2010) Characterization of chow-chow (Sechium edule) germplasm of North-Eastern region of India for economic traits. Indian J Plant Genet Resour 23(1):19–21

Sateesh G, Hussaini SF, Kumar GS, Rao BSS (2012) Anti-ulcer activity of Sechium edule ethanolic fruit extract. Pharm Innov 1(5):77–81

Seyedimoradi H, Talebi R, Hassani D, Karami F (2012) Comparative genetic diversity analysis in Iranian local grapevine cultivars using ISSR and DAMD molecular markers. Environ Exp Bot 10:125–132

Acknowledgements

Authors thank the management of Jain University—Centre of Post Graduate Studies, Bangalore, India for providing necessary facilities to carry out the present investigation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jain, J.R., Timsina, B., Satyan, K.B. et al. A comparative assessment of morphological and molecular diversity among Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw. accessions in India. 3 Biotech 7, 106 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-017-0726-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-017-0726-5