Abstract

EBV-positive B cell proliferations have been recognized in the setting of some T cell lymphomas. These B cell proliferations often differ to varying degrees in morphology and immunophenotype with a great proportion being Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive with Reed-Sternberg (RS)-like morphology. We describe a case of a 76-year-old Caucasian male who presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with weight loss, abdominal pain, and multiple episodes of vomiting and diarrhea. He underwent a laparotomy with an intraluminal mass seen in the cecum. Histology showed atypical intermediate- to large-sized cells involving the full thickness of the bowel wall with numerous mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies. The adjacent uninvolved mucosa demonstrated villous blunting, increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, crypt elongation, and lamina propria plasmacytosis, consistent with the celiac enteropathy. Rare large transformed cells morphologically consistent with Reed-Sternberg cells (RS cells) were also identified in the mesenteric lymph nodes. Immunophenotyping showed the intermediate- to large-sized cells to be of T cell origin with strongly CD3, CD45, and TIA-1 positive; moderately positive for CD5; and variably positive for CD2, CD25, CD57, perforin, and granzyme B, with an aberrant loss of CD7. The large cells were moderately positive for PAX-5, CD79a, CD20, CD30, and MUM1. They also were positive for EBV latent membrane protein (EBV-LMP) and Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNA (EBER). Based on morphology and immunoprofile, a diagnosis of enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma (EATL) with Reed-Sternberg-like cells associated with EBV virus infection was made. This is a rare phenomenon; the presence of large B cell proliferations in EATL, to our knowledge, is yet to be reported.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

EBV-positive B cell proliferations have been increasingly recognized in the setting of some T cell lymphomas [1,2,3]. This feature has been described in association with lymphomas derived from follicular helper T cells like angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma (AITL) and the follicular variant of peripheral T cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS) [2, 3]. These B cell proliferations often differ to varying degrees in morphology and immunophenotype with a great proportion being Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive with Reed-Sternberg (RS)-like morphology [2, 3]. The etiology of the EBV-positive RS-like cells or large B cells in T cell lymphoma is multi-faceted and ranges from reactive to neoplastic [1, 4]. This further complicates the pathogenesis of these diseases. Their presence may lead to challenges in the diagnosis of T cell lymphomas and should not be mistaken for a large B cell lymphoproliferative disorder or classic Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL). This is especially important in cases of intestinal T cell lymphomas, as B cell lymphomas occur more commonly than T cell lymphomas in the gastrointestinal tract [5]. Accurate diagnosis relies on an extensive immunohistochemical investigation, with or without molecular analysis. We present a case of enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma (EATL) with Reed-Sternberg-like cells associated with EBV virus infection.

Clinical history

A 76-year-old Caucasian male with a history of celiac disease, pancreatitis, factor V deficiency, and supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with weight loss and a 3-day history of abdominal pain. He also complained of multiple episodes of vomiting and diarrhea.

Physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, with diffuse tenderness. He was tachycardic (126 beats per minute). Other vital signs were normal. Laboratory tests showed elevated lactic acid (8.3 mmol/L), mild renal dysfunction (BUN 40 mg/dL, creatinine 2.3 mg/dL), and leukocytosis (46.0 x 103/휇L) with a left shift. Red cell and platelet counts were within normal limits. He was suspected to have a bowel perforation and an emergent exploratory laparotomy was performed. At surgery, a large intraluminal mass was identified in the cecum involving the mesentery as well as multiple palpable smaller masses along the jejunum and ileum. A small perforation at the distal jejunum and possible necrosis were present. There was a small to moderate volume of frank pus in the abdomen. The involved segments of the jejunum, ileum, and cecum were resected. The patient was taken to the intensive care unit (ICU) where he remained intubated and on vasopressor support.

A repeat laparotomy was carried out on postoperative day 1 on account of worsening clinical condition. The terminal ileum and cecum along with the sigmoid colon were found to be necrotic and were all resected. He had the rest of his terminal colon removed in a subsequent surgery.

Over the course of his hospital stay, the patient’s condition gradually deteriorated with several episodes of emesis, altered mental status, and a gradually distending abdomen. He had a cardiac arrest, and despite cardiopulmonary resuscitation, he was declared dead 10 days after admission.

Materials and methods

Specimens were submitted and processed in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University Medical Center, New Orleans, according to established protocols.

The tissue sections were submitted in formalin, processed, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or other special and immunohistochemical stains, as required.

The specimens for flow cytometry were collected in tissue culture medium (RPMI) and were analyzed using a multiparameter 8 color flow cytometer. Solid tissue was refrigerated (2–8 °C or 36–46 °F). The antibody panel was determined by the clinical history and/or review of stained slides.

Results

Macroscopic examination of the specimen from the initial laparotomy consisted of a 62-cm segment of the small intestine with associated mesentery. Along the length of the small intestine were multiple discreet mucosa-centric lesions ranging from 0.4 to 4.8 cm in greatest dimension. There was associated mucosal ulceration and an area of perforation measuring 0.7 cm. The larger lesions extended through the muscularis propria and subserosal soft tissue to involve the serosal surface. Also found were 30 mesenteric lymph nodes.

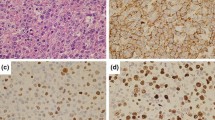

Microscopic examination showed the small intestinal lesions to consist of dense and diffuse atypical lymphoid infiltrates comprised of intermediate- to large-sized cells involving the full thickness of the bowel wall (Fig. 1a, b). Numerous mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies were seen. The adjacent uninvolved mucosa demonstrated villous blunting, increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, crypt elongation, and lamina propria plasmacytosis, consistent with the celiac enteropathy (Fig. 2). The mesenteric lymph nodes showed partial involvement by the same atypical lymphoid cells noted in the small intestine. Furthermore, rare large transformed cells morphologically consistent with Reed-Sternberg cells (RS cells) were also identified in the mesenteric lymph nodes (Fig. 3a), but not appreciated in the small intestine.

Microscopy showing an admixture of intermediate- to large-sized atypical lymphocytes (a x 200; b x 400). The intermediate- to large-sized atypical cells showing diffuse positivity for CD3 (c x 200), negative expression of CD4 (d x 200), aberrant loss of CD7 (e x 200), and negative expression of CD8 (f x 200)

Immunohistochemically, the intermediate- to large-sized atypical lymphoid cells were noted to be of T cell origin with strong diffuse positivity for CD3, CD45, and TIA-1; moderate diffuse positivity for CD5; variable positivity for CD2, CD25, CD57, perforin, and granzyme B; and aberrant loss of CD7. The cells were negative for CD4, CD8, CD10, CD15, CD20, CD30, CD56, CD79a, PAX-5, EMA, EBV-LMP, and EBER (Fig. 1c–f). The Ki-67 proliferation index in these cells on average was 70%.

In contrast to these atypical T cells, the scattered large cells morphologically consistent with RS cells demonstrated a B cell phenotype with moderate positivity for PAX-5, CD79a, CD20, CD30, and MUM1. They were negative for CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD7, CD8, CD10, CD15, CD45, CD56, CD57, TIA-1, granzyme B, perforin, and EMA. In addition, these RS-like cells were positive for EBV-LMP and EBER (Fig. 3b–e). They also had a high Ki67 proliferation index.

Reactive T cells present in the background were positive for CD7 and expressed strongly CD2, CD3, CD5, and CD45. They consisted of a mixture of CD4+ and CD8+ forms.

Flow cytometric testing performed on an unfixed portion of the small bowel revealed a 58.1% population of immunophenotypically aberrant variable-sized T cells that were characterized as CD3 (partial dim), CD4 (negative), CD8 (negative), CD2 (dim to moderate), CD5 (moderate), CD7 (negative), CD16 (negative), CD30 (negative), CD56 (negative), TCR alpha beta (partial dim), and TCR gamma delta (negative).

Given the patient’s reported history of celiac disease, the multifocal mucosa centric nature of small intestine involvement by the T cell lymphoma and the histopathologic features of uninvolved small intestine mucosa consistent with celiac enteropathy, alongside the immunohistochemical findings, the patient was diagnosed to have EATL with multifocal involvement of the small intestine and focal involvement of the mesenteric lymph nodes with associated Reed-Sternberg-type cells of B cell phenotype. Flow cytometry results also supported this diagnosis.

Discussion

Enteropathy-associated T cell lymphoma (EATL) is a rare gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma originating from intraepithelial T lymphocytes that occur in individuals with celiac disease [5], an autoimmune disorder of the small intestine [5]. Previously designated as EATL type I, it comprises about 80–90% of all primary intestinal T cell lymphomas [6, 7]. The annual incidence of EATL is 0.5–1 per million people per year in Western countries [6,7,8]. EATL presents most commonly in the sixth and seventh decades of life. There is a slight male predominance [6, 7, 9]. The small intestine is the most common site of involvement, followed by the stomach, colon, and rectum [10]. Most patients present late in the course of the disease as a result of non-specific clinical manifestations of the disease. Acute abdomen, small bowel obstruction, and intestinal perforation account for approximately half of the initial presentations. Other presentations include weight loss, malabsorption, and protein-losing enteropathy, which are all symptoms of celiac disease thereby making the distinction between patients with and without EATL challenging [10, 11]. Monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T cell lymphoma (MEITL), which also originates from intraepithelial lymphocytes, was previously designated as EATL type II. It is not associated with celiac disease and has important morphologic and immunophenotypic differences from the “classic” form of EATL. Due to these distinctions, the 2016 WHO classification formally separated these 2 entities and now defines MEITL as a primary intestinal T cell lymphoma that is not associated with celiac disease [12, 13].

There has been a recognition of abnormal B cell expansions as a component of certain T cell lymphomas. This has been described mainly in conjunction with angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma (AITL) and also the follicular variant of peripheral T cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS) [2, 3, 14,15,16]. A great proportion of these B cell lympho-proliferations are Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive with Reed-Sternberg (RS)-like cells of B cell derivation identified in some cases [2, 3].

The large bi- or multinuclear cells with prominent eosinophilic cytoplasm, now known as Reed-Sternberg cells, were initially described and identified at the turn of the 20th century as the hallmarks of classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma (CHL) [17]. Their identity as clonal B lineage cells has been confirmed through immunoglobulin gene-rearrangement studies [18, 19]. The typical immunophenotype of RS cells and mononuclear variants (Hodgkin cells) is CD15+, CD30+, CD20−/+, CD3−, CD45−, and PAX-5+ (weak). Some cases of CHL include evidence of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection [20].

Cells with a morphologic appearance indistinguishable from RS cells have been found in the absence of CHL. They have been observed to occur in some B cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs), most notably B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) as a unique type of Richter transformation [21, 22].

Many T cell lymphomas such as PTCL-NOS and AITL may also harbor RS-like cells [2, 3, 14,15,16]. Quintanilla-Martinez et al. noted that EBV-positive cells could assume both the morphology and immunophenotype of RS cells [14]. This may lead to a diagnostic dilemma as it may be difficult to distinguish these cases from CHL as the background mixed inflammatory picture of histiocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells can be seen in both T cell lymphomas and CHL.

The current report discusses a patient with characteristics consistent with EATL. Because EATL is an aggressive malignancy and is frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage, it tends to have a poor outcome with a dismal 5-year survival of less than 20% [7, 16, 23]. Most deaths occur as a result of septicemia or complications associated with gastrointestinal tract perforation [10]. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms designates EATL only to be used for cases formerly known as type I EATL, which are typically associated with celiac disease [12]. In our case, increased numbers of intraepithelial T cells are seen in small intestinal mucosa uninvolved by lymphoma, consistent with celiac enteropathy. Typically, EATL is positive for CD3, CD7, and cytotoxic markers (TIA-1, perforin, and granzyme B) and is negative for CD4, CD5, CD8, and CD56 [24]. The immunophenotype of this current case, while positive for CD3 and cytotoxic markers and negative for CD4, CD8, and CD56, is unusually CD5 positive and CD7 negative. The significance of this atypical phenotype is uncertain; however, given the clinical and morphological features of this case, it likely represents a phenotypically unusual variant of EATL.

In contrast to the prevalent T cell lymphoma in this case, the RS-like cells exhibit a B cell phenotype and are positive for EBV (both EBV-LMP and EBER). These cells are not considered to be clonally related to the concurrent T cell lymphoma. It has been hypothesized that their appearance is a result of a defective immune system due to the underlying T cell lymphoma [14]. In most cases, these RS-like cells are EBV-positive (as noted in this case) suggesting an EBV-driven process potentiated by inhibited immune surveillance [2, 25]. More recently, reports of clonal and oligoclonal EBV-negative B cell populations suggest that other mechanisms than EBV infection contribute to promote the B cell proliferation [3, 16, 26]

While these RS-like cells seen in these cases may be immunophenotypically identical to those seen in CHL, their clinical significance remains undetermined. It has been suggested that some of the cases possibly represent a starting point for the development of an EBV-positive B cell lymphoma [26, 27]. However, limited follow-up data has not shown progression to disseminated B cell lymphoma following treatment of the underlying T cell lymphoma [3]. Thus, the principal target of therapy of similar cases should be the T cell lymphoma.

In conclusion, we present a case of a presentation of EATL complicated by the unusual presence of RS-like cells of B cell phenotype and EBV infection. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report documenting the presence of RS-like cells of B cell phenotype in a case of EATL. The presence of RS-like cells of B cell phenotype in T cell lymphomas may lead to a diagnostic dilemma to pathologists, and an extensive immunohistochemical investigation is often needed for an accurate diagnosis.

References

Higgins JP, van de Rijn M, Jones CD, Zehnder JL, Warnke RA (2000) Peripheral T-cell lymphoma complicated by a proliferation of large B cells. Am J Clin Pathol 114:236–247

Willenbrock K, Brauninger A, Hansmann ML (2007) Frequent occurrence of B-cell lymphomas in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and proliferation of Epstein-Barr virus-infected cells in early cases. Br J Haematol 138:733–739

Nicolae A, Pittaluga S, Venkataraman G, Vijnovich-Baron A, Xi L, Raffeld M, Jaffe ES (2013) Peripheral T-cell lymphomas of follicular T-helper cell derivation with Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells of B-cell lineage: both EBV-positive and EBV-negative variants exist. Am J Surg Pathol 37:816–826

Smuk G, Illes A, Keresztes K, Kereskai L, Marton B, Nagy Z, Lacza A, Pajor L (2010) Pheno- and genotypic features of Epstein-Barr virus associated B-cell lymphoproliferations in peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Pathol Oncol Res 16:377–383

Brousse N, Meijer JW (2005) Malignant complications of coeliac disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 19:401–412

Verbeek WH, Van De Water JM, Al-Toma A, Oudejans JJ, Mulder CJ, Coupe VM (2008) Incidence of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: a nation-wide study of a population-based registry in The Netherlands. Scand J Gastroenterol 43:1322–1328

Delabie J, Holte H, Vose JM, Ullrich F, Jaffe ES, Savage KJ, Connors JM, Rimsza L, Harris NL, Muller-Hermelink K, Rudiger T, Coiffier B, Gascoyne RD, Berger F, Tobinai K, Au WY, Liang R, Montserrat E, Hochberg EP, Pileri S, Federico M, Nathwani B, Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD (2011) Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: clinical and histological findings from the international peripheral T-cell lymphoma project. Blood 118:148–155

Sharaiha RZ, Lebwohl B, Reimers L, Bhagat G, Green PH, Neugut AI (2012) Increasing incidence of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma in the United States, 1973-2008. Cancer 118:3786–3792

Malamut G, Chandesris O, Verkarre V, Meresse B, Callens C, Macintyre E, Bouhnik Y, Gornet JM, Allez M, Jian R, Berger A, Chatellier G, Brousse N, Hermine O, Cerf-Bensussan N, Cellier C (2013) Enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma in celiac disease: a large retrospective study. Dig Liver Dis 45:377–384

Yang Y, Batth SS, Chen M, Borys D, Phan H (2012) Enteropathy-associated T cell lymphoma presenting with acute abdominal syndrome: a case report and review of literature. J Gastrointest Surg 16:1446–1449

Zhang JC, Wang Y, Wang XF, Zhang FX (2016) Type I enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma in the colon of a 29-year-old patient and a brief literature review. Onco Targets Ther 9:863–868

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, Advani R, Ghielmini M, Salles GA, Zelenetz AD, Jaffe ES (2016) The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 127:2375–2390

Weindorf SC, Smith LB, Owens SR (2018) Update on gastrointestinal lymphomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med 142:1347–1351

Quintanilla-Martinez L, Fend F, Moguel LR, Spilove L, Beaty MW, Kingma DW, Raffeld M, Jaffe ES (1999) Peripheral T-cell lymphoma with Reed-Sternberg-like cells of B-cell phenotype and genotype associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. Am J Surg Pathol 23:1233–1240

Zettl A, Lee SS, Rudiger T, Starostik P, Marino M, Kirchner T, Ott M, Muller-Hermelink HK, Ott G (2002) Epstein-Barr virus-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders in angloimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified. Am J Clin Pathol 117:368–379

Gru AA, Haverkos BH, Freud AG, Hastings J, Nowacki NB, Barrionuevo C, Vigil CE, Rochford R, Natkunam Y, Baiocchi RA, Porcu P (2015) The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in T cell and NK cell lymphomas: time for a reassessment. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 10:456–467

Rengstl B, Kim S, Doring C, Weiser C, Bein J, Bankov K, Herling M, Newrzela S, Hansmann ML, Hartmann S (2017) Small and big Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin lymphoma cell lines L-428 and L-1236 lack consistent differences in gene expression profiles and are capable to reconstitute each other. PLoS One 12:e0177378

Cossman J, Annunziata CM, Barash S, Staudt L, Dillon P, He WW, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Rosen CA, Carter KC (1999) Reed-Sternberg cell genome expression supports a B-cell lineage. Blood 94:411–416

Kuppers R, Brauninger A (2006) Reprogramming of the tumour B-cell phenotype in Hodgkin lymphoma. Trends Immunol 27:203–205

Wang L, Levenson B (2014) Peripheral T-cell lymphoma with Epstein-Barr virus-positive Reed-Sternberg-like B-cells in a 59-year-old Hispanic man. Lab Med 45:342–346

de Leval L, Vivario M, De Prijck B, Zhou Y, Boniver J, Harris NL, Isaacson P, Du MQ (2004) Distinct clonal origin in two cases of Hodgkin’s lymphoma variant of Richter’s syndrome associated With EBV infection. Am J Surg Pathol 28:679–686

Mao Z, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Raffeld M, Richter M, Krugmann J, Burek C, Hartmann E, Rudiger T, Jaffe ES, Muller-Hermelink HK, Ott G, Fend F, Rosenwald A (2007) IgVH mutational status and clonality analysis of Richter's transformation: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma in association with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) represent 2 different pathways of disease evolution. Am J Surg Pathol 31:1605–1614

van de Water JM, Cillessen SA, Visser OJ, Verbeek WH, Meijer CJ, Mulder CJ (2010) Enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma and its precursor lesions. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 24:43–56

Arps DP, Smith LB (2013) Classic versus type II enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: diagnostic considerations. Arch Pathol Lab Med 137:1227–1231

Dunleavy K, Wilson WH, Jaffe ES (2007) Angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma: pathobiological insights and clinical implications. Curr Opin Hematol 14:348–353

Balague O, Martinez A, Colomo L, Rosello E, Garcia A, Martinez-Bernal M, Palacin A, Fu K, Weisenburger D, Colomer D, Burke JS, Warnke RA, Campo E (2007) Epstein-Barr virus negative clonal plasma cell proliferations and lymphomas in peripheral T-cell lymphomas: a phenomenon with distinctive clinicopathologic features. Am J Surg Pathol 31:1310–1322

Zaki MA, Wada N, Kohara M, Ikeda J, Hori Y, Fujita S, Ogawa H, Sugiyama H, Hino M, Kanakura Y, Morii E, Aozasa K (2011) Presence of B-cell clones in T-cell lymphoma. Eur J Haematol 86:412–419

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nwanze, J.A., Schmieg, J. Enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma with Reed-Sternberg-like cells of B cell phenotype and genotype associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Hematopathol 12, 201–206 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-019-00375-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-019-00375-7