Abstract

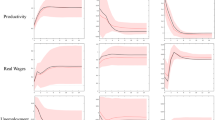

This paper investigates the structural relation between the Italian weak macroeconomic performances and the productivity decline experienced over the last 15 years, estimating a Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium model. Modifying Ireland and Schuh’s (Rev Econ Dyn 11:473–492, 2008) two-sector RBC model in order to account for cointegration between consumption and investment, we interpret the unsatisfactory Italian economic dynamics in the light of a permanent negative shock to the component of productivity which is common across the consumption-good and the investment-good sector. In the light of our results, the common view that the Italian productivity problems involve only the Made in Italy sectors is only partially confirmed, since growth in the investment-good sector relies on the counterbalancing properties of its transitory sector-specific productivity component. Moreover, the model indirectly stresses the importance of the intermediate-good productions in the observed productivity decline. The short- and long-run implications of productivity dynamics for consumption, investment and hours worked are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Linearity in leisure is consistent with the view that the economy is compound by a large number of households, each including a potential employee who either works full time or not at all in each period (Hansen 1985).

Part-time contracts have been introduced for the fist time in 1984. The “pacchetto Treu” in 1997 and the Biagi’s reform in 2003 introduced and increased the variety of fixed-term labour contracts.

We computed \(\delta \) from the annual series of gross capital (\(K_{t}\)) and investment (\(I_{t}\)) in the non-farm sector, provided by ISTAT, using the steady-state property of the aggregate law of motion of capital, given by the sum of the Eqs. (4) and (5), so that \(I_{ss}/K_{ss}=\delta \). The annual depreciation rate, obtained as the average of the ratio I/K over the period 1981–2007, is then converted into the corresponding quarterly value.

We first computed the (simple) average of labour income shares \(\alpha \) for the period 1981–2007. The average capital income share is derived as \(1-\alpha \), exploiting the property of a Cobb–Douglas function with constant returns to scale.

Given our sample size, the choice to go through a maximum likelihood approach is preferable; indeed, the information contained in the data would have dominated the information in the priors in a Bayesian framework, and the results would have been not very different from those obtained by maximum likelihood. This is the same choice made by Ireland and Schuh (2008).

From Mario Draghi’s 2007 speech as former Governor of the Bank of Italy.

References

Aiello F, Mastromarco C, Zago A (2011) Be productive or face decline. On the sources and determinants of output growth in Italian manufacturing firms. Empir Econ 41(3):787–815

Aiello F, Pupo V, Ricotta F (2009) Sulla Dinamica della Produttività Totale dei Fattori in Italia: un’analisi settoriale. Rivista di Economia e Politica Industriale (3):413–436. doi:10.1430/30002

Bassanetti A, Iommi M, Jona-Lasinio C, Zollino F (2004) La crescita dell’economia italiana negli anni novanta tra ritardo tecnologico e rallentamento della produttività, Bank of Italy, Economic Research Department, Temi di discussione, No 539, December 2004

Belbute JM, Caleiro A (2013) Cross country evidence on consumption persistence. Int J Latest Trends Finance Econ Sci 3(2):440–455

Boeri T, Garibaldi P (2007) Two tier reforms of employment protection: a honeymoon effect? Econ J R Econ Soc 117(521):357–385, 06

Chiarini B, Piselli P (2005) Business cycle, unemployment benefits and productivity shocks. J Macroecon 27(4):670–690

Daveri F, Jona-Lasinio C (2005) Italy’s decline: getting the facts right. Giornale degli Economisti e Annali di Economia 64(4):365–410

Del Boca A, Rota P (1998) How much does hiring and firing cost? Survey evidence from a sample of Italian firms. Labour 12:427–449

Greenwood J, Hercowitz Z, Krusell P (2000) The role of investment-specific technological change in the business cycle. Eur Econ Rev 44:91–115

Greenwood J, Hercowitz Z, Krusell P (1997) Long-run implications of investment-specific technological change. Am Econ Rev 87:342–362

Greenwood J, Hercowitz Z, Huffman GW (1988) Investment, capital utilization, and the real business cycle. Am Econ Rev 78(3):402–417

Gruber JW (2004) A present value test of habits and the current account. J Monet Econ 51(7):1495–1507

Hamilton JD (1994) Time series analysis. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Hansen GD (1985) Indivisible labour and the business cycle. J Monet Econ 16(1985):309–327 (North Holland)

Inoue A, Rossi B (2011) Identifying the sources of instabilities in macroeconomic fluctuations. Rev Econ Stat 93(4):1186–1204

Ireland PN (2013) Stochastic growth in the Unites States and Euro area. J Eur Econ Assoc 11:1–24. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2012.01108.x

Ireland PN, Schuh S (2008) Productivity and US macroeconomic performance: interpreting the past and predicting the future with a two-sector real business cycle model. Rev Econ Dyn 11(2008):473–492

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica ISTAT (2010) Rapporto Annuale, Rome

King RG, Plosser CI, Stock JH, Watson MW (1991) Stochastic trends and economic fluctuations. Am Econ Rev 81(4):819–840

King RG, Plosser CI, Rebelo ST (1988) Production, growth and business cycles: II. New directions. J Monet Econ 21(2–3):309–341

Kydland Finn E, Prescott Edward C (1982) Time to build and aggregate fluctuations. Econ Econ Soc 50(6):1345–1370

Klein P (2000) Using the generalized Schur form to solve a multivariate linear rational expectation model. J Econ Dyn Control 24:1405–1423

Maffezzoli M (2001) Non-walrasian labor markets and real business cycles. Rev Econ Dyn 4(4):860–892

Mastromarco C, Zago A (2012) On modelling the determinants of TFP growth. Struct Change Econ Dyn 23(4):373–382

Milana C, Nascia L, Zeli A (2013) Decomposing multifactor productivity in Italy from 1998 to 2004: evidence from large firms and SMEs using DEA. J Product Anal 40(1):99–109

Orsi R, Turino F (2014) The last fifteen years of stagnation in Italy: a business cycle accounting perspective. Empir Econ 47(2):469–494

Pacelli L (2002) Fixed term contracts, social security rebates and labour demand in Italy. LABORatorio R. Revelli working papers series No. 7 LABORatorio R. Revelli, Centre for Employment Studies

Pakko MR (2002) What happens when the technology growth trend changes? Transition dynamics, capital growth, and the “new economy”. Rev Econ Dyn 5:376–407

Pakko MR (2005) Changing technology trends, transition dynamics, and growth accounting. Contrib Macroecon 5(1). doi:10.2202/1534-6005

Rota P (2001) Dynamic labour demand with lumpy and kinked adjustment costs, FEEM Working Paper No. 20.2001, available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=275873

Saltari E, Travaglini G (2009) The productivity slowdown puzzle. Technological and non-technological shocks in the labor market. Int Econ J 23(4):483–509

Schmitt-Grohe S, Uribe M (2011) Business cycles with a common trend in neutral and investment-specific productivity. Rev Econ Dyn 14(1):122–135

Sgherri S (2005) Long-run productivity shifts and cyclical fluctuations: evidence from Italy, IMF working paper 05/228, International Monetary Fund

van Ark B, O’Mahony M, Ypma G (eds) (2007) The EU KLEMS productivity report, WP2007-1 Policy Support and Anticipating Scientific and Technological Needs, European Commission

Venturini F (2004) The determinants of Italian slowdown: what do the data say, EPKE working paper no. 29, NIESR, London

Whelan K (2003) A two-sector approach to modelling US NIPA data. J Money Credit Bank 35:627–656

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This paper benefited from the comments and suggestions of Ulrich Woitek, Mathias Hoffmann and the participants at the Fifth Italian Congress of Econometrics and Empirical Economics (ICEEE 2013) in Genova.

Appendix: Equilibrium conditions in the common-trend model

Appendix: Equilibrium conditions in the common-trend model

The Social Planner’s problem consists of choosing

so that the social utility function is maximized, subject to the production and capital accumulation constraints. Denote by \(\Lambda _{ct}\) and \(\Lambda _{it}\) the non-negative Lagrange multipliers on the technology constraints (2)–(3), and by \(\Xi _{ct}\) and \(\Xi _{it}\) the non-negative Lagrange multipliers on the capital accumulation constraints (4)–(5), then the first-order conditions (FOC) derived from the Lagrangian of the planner’s problem are given by:

for \(t=0,1,2,\ldots ,\) where

and

The first-order conditions (21)–(31), along with the aggregation constraints (32)–(33) and the driving processes, as specified in (6)–(13) in the main text, are the equilibrium conditions of the model. This is a system of 21 equations in 21 variables—\(C_{t}\), \(H_{t}\), \(H_{ct}\), \(H_{it}\), \(I_{t}\), \(I_{ct}\), \(I_{it}\), \(K_{ct}\), \(K_{it}\), \(\Lambda _{ct}\), \(\Lambda _{it}\), \(\Xi _{ct}\), \(\Xi _{it}\), \(A_{t}\), \(a_{t}^{l}\), \(A_{t}^{g}\), \(Z_{ct}\), \(z_{ct}^{l}\), \(Z_{it}\), \(z_{it}^{l}\) and \(Z_{t}^{g}\). However, the equilibrium deriving from the solution of this system is not stable, since variables grow and some of them also may also be non-stationary. Following Ireland and Schuh (2008), this system can then be written in terms of the stationarized variables, i.e. variables that are constant in the steady state, obtained dividing the original ones by the sources of non-stationarity assigned to them by the model, so that

while \(a_{t}^{l}\), \(z_{ct}^{l}\), \(z_{it}^{l}\) remain the same, since already stable. The new system is obtained substituting the original variables with their stationary counterparts; however, in order to keep track of the three key original variables, \(C_{t}\), \(H_{t}\) and \(I_{t}\), which are our observables, we need to introduce three further variables, \(g_{t}^{c}\), \(g_{t}^{i}\) and \(g_{t}^{h}\), corresponding to their growth rates and defined as

The final system consists of 24 equations in 24 variables and can be log-linearized around the steady state of the lower-case variables and solved using Klein’s (2000) method.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marino, F. The Italian productivity slowdown in a Real Business Cycle perspective. Int Rev Econ 63, 171–193 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-015-0248-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-015-0248-6